CRISPR/Cas (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats linked to Cas nuclease) technology has revolutionized many aspects of genetic engineering research. The changes introduced by the CRISPR/Cas system are based on the repair paths of the single or double strand DNA breaks that cause insertions, deletions, or precise integrations of donor DNA.

- CRISPR/Cas

- genetic engineering

1. Introduction

The increasing human life expectancy has led to an increase in the number of patients with chronic diseases and severe organ failure. Organ transplantation is an effective approach in the treatment of end-stage organ failure [1]. However, the imbalance between the supply of and the demand for human organs is a serious problem in contemporary transplantology. Since 2013, the rapid growth in interest in xenotransplantation has been related to the CRISPR/Cas technology appearance in genetic engineering [2].

2. CRISPR/Cas Technology

1. Origin and Mechanism of Action

2.1. Origin and Mechanism of Action

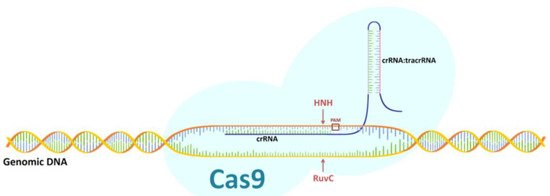

The CRISPR/Cas system has been described in bacteria and archaea as their acquired ‘immunity’ mechanism against viruses. It works by recognizing and hydrolyzing pathogen genetic material by means of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) associated with CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) nuclease [1][2][2,3]. The CRISPR/Cas system has been observed in 40% of bacteria and almost 90% of archaea whose genomes have been sequenced so far [3][4]. The CRISPR locus consists of a series of conserved repeating sequences interspersed with sequences called linker sequences. After entering the bacterial cell, the phage genome is hydrolyzed by Cas (Cas1 or Cas2) nuclease into small fragments of DNA, which are then inserted into the CRISPR locus of the host genome between linker sequences (as spacers). In response to a subsequent viral infection, spacer sequences are used as templates for the transcription of crRNA, which in combination with the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) and the different Cas protein (e.g., Cas9 or Cas12) hydrolyze the target sequences of the genetic material of invading phages [1][4][2,5]. More than 40 different families of Cas proteins have been described. They are divided into three main types based on their sequences and structures, I, II, and III, and three others, IV, V, and VI. The presence of other types has also been confirmed. The CRISPR/Cas type II system requires only one Cas protein to function, Cas9, which contains the HNH nuclease domain and the RuvC nuclease-like domain, and therefore it has found application in genetic engineering. CRISPR/Cas9 has been shown to be a simple and efficient genome editing tool [1][2].

The CRISPR/Cas9 system was first used in genetic engineering in 2013 [5][6]. Editing the genome through it depends on the formation of a double-strand break (DSB) and the subsequent cellular DNA repair processes [6][7]. One of these processes is repair by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), and the other is homology directed repair (HDR), which is based on the homologous recombination mechanism that appears with the delivery of appropriately designed donor DNA [7][8]. In the bacterial CRISPR/Cas9 system, the mature crRNA binds to tracrRNA to form a tracrRNA:crRNA complex that partially binds to the Cas9 and guides the entire system to its target site [1][2]. The crRNA-specific hydrolysis of both DNA strands via CRISPR/Cas9 requires the presence of a complementary target sequence in the DNA, followed immediately by a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence. After the complementary connection of the crRNA molecule with the target site within one DNA strand, it is hydrolyzed by the Cas9 HNH nuclease domain, while the hydrolysis of the complementary DNA strand to the recognized target site is carried out by the Cas9 RuvC nuclease-like domain. This creates a two-strand DNA break three nucleotides downstream of the PAM sequence [8][9]. In genetic engineering, single-guide RNA (sgRNA) is used, which is the equivalent of the bacterial chimera: crRNA:tracrRNA (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagram of CRISPR/Cas9 system. Description of a figure in the text.

In the sgRNA sequence, gRNA is distinguished as an element corresponding to the bacterial crRNA fragment that complements the target locus in DNA. The gRNA molecule is an element designed by the researcher [1][2]. Many variants of the CRISPR/Cas9 system have been developed in which the engineered gRNA recognizes a sequence from 18 to 24 nucleotides in length and Cas9 recognizes different PAM sequences from two to eight nucleotides in length. In genetic engineering, the system most commonly used is that found in Streptococcus pyogenes. It requires a 20-nucleotide gRNA molecule linked to a Cas9 nuclease and a three-nucleotide-long PAM sequence (specifically NGG, where N is an arbitrary base nucleotide followed by two guanosine nucleotides) [9][10].

2. Mechanisms of Repairing Double-Stranded DNA Breaks

2.2. Mechanisms of Repairing Double-Stranded DNA Breaks

Double-strand breaks generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system may be repaired by DNA non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or by homology directed repair (HDR). The HDR mechanism is based on homologous recombination, which takes place after delivery an appropriately designed donor DNA) [7][10][8,11].

NHEJ-mediated DNA repair generates small mutations such as insertions or deletions (indels) at the target sites. These mutations may interfere with/or abolish the function of target genes or genomic elements. It is known that the NHEJ process can occur by two pathways: classical (cNHEJ) and alternative (aNHEJ).

In mammals, the cNHEJ mechanism starts with the attachment of a DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) complex to the DSB. In eukaryotes, the DNA-PK complex includes the Ku protein, composed of the two polypeptides, Ku70 and Ku80, as well as the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs) catalytic subunit. The Ku protein is a molecular scaffold that enables the attachment of subsequent elements involved in the repair of the DNA double-strand breaks. In the next steps, the damaged or mismatched nucleotides are removed with Artemis nuclease. Then, the gap is filled with the λ polymerase or the μ polymerase. The final step is the ligation of the DNA ends with the DNA ligase IV complex consisting of the DNA ligase IV catalytic subunit and its cofactor [7][10][11][8,11,12]. The cNHEJ mechanism does not require the presence of microhomological sequences to work; however, when such fragments are present within the joined ends of the DNA, they can positively affect the connection of the DSB [12][13][13,14]. Moreover, it is known that cNHEJ is used more frequently when the cell is in the G0/G1 phase of mitosis [14][15].

The alternative HNEJ is also known as backup-NHEJ or microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) [12][13]. In contrast to the cNHEJ, the alternative pathway often leads to large deletions, as this form of repair is most often based on microhomological sequences [15][16]. Therefore, in addition to large deletions, chromosomal translocations based on microhomological sequences are also observed [16][17][17,18]. This type of repair occurs mainly when the classic pathway is turned off or not fully functional (especially in the absence of Ku proteins) and relies on the polymerase θ [18][19][19,20].

Double-stranded DNA breaks can also be repaired by homologous recombination in the presence of an appropriately designed DNA construct. Homologous recombination takes place on a DNA template flanked with fragments complementary to the blunt ends of the DSB, called homologous arms [20][21]. Three models of homologous recombination are described: the Holliday model, the Meselson–Radding model (or the Aviemore model), and the Szostak model (or the double strand break model) [21][22]. Repairing HDR requires the presence of enzymes that allow DNA fragments to be joined together. A key role in this repair is played by the RAD51 protein, which mediates ATP-dependent DNA strand exchange. RAD51 enables quick searches of DNA fragments for homologous sequences and then facilitates strand exchange at the homology site. Homologous genome modification can be used to insert the desired genetic material, editing the genome of the target cell with high precision [22][23][23,24].

3. Difficulties and Limitations of Technology

2.3. Difficulties and Limitations of Technology

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is not without limitations, mainly related to the formation of DNA breaks outside the target locus—off-target mutations—and dependence on the PAM sequence. Off-targets are one of the major concerns in genome editing via the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Compared to the use of zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) and TALE nuclease, the CRISPR/Cas9 system has a higher risk of developing off-target mutations in human cells [24][25]. This is related to genome size, as the larger the genome, the more DNA sequences that are identical or highly homologous to the target DNA sequences. In addition to target sequences, Cas9 nuclease linked to sgRNA hydrolyzes highly homologous DNA sequences, leading to mutations at undesirable sites [9][25][26][10,26,27]. Mutations outside the target site can lead to the dysfunction of some genes and sometimes even cell death. To ensure greater precision and specificity of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, it is necessary to select a target locus with as few potential off-target sites as possible at the bioinformatic analysis stage [27][28]. In addition, a modified Cas9—Cas9-D10A—nuclease with nickase activity was developed to minimize the formation of mutations in undesirable places. The Cas9-D10A in combination with sgRNA leads to the hydrolysis of one DNA strand at the target site. To obtain the hydrolysis of both DNA strands within a given target site, a system based on nickase Cas9-D10A and two sgRNAs should be designed, one of which is complementary to the coding strand and the other to the DNA template strand [28][29]. In this way, we can reduce the risk of mutations in undesirable places, while maintaining the precision of introducing modifications at the target locus. Another method is to use the truncated gRNAs containing 15 or fewer nucleotides. Shorter gRNAs have been shown to reduce mismatch tolerance and consequently reduce off-target frequency [29][30]; however, only sgRNA above 17 nt long efficiently led to the formation of changes at the target site [30][31]. It is also possible to use high-fidelity endonuclease variant of Cas9 protein, e.g., HypaCas9, which proved to be effective in modifying the target locus, while minimizing off-target effects [31][32]. It has also been shown that modifying standard SpCas9 to recognize an altered PAM sequence may reduce the amount of the off-target mutations [32][33]. Furthermore, the method of delivering the CRISPR/Cas9 system to the cells is of great importance. Delivery of the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex has been shown to minimize the off-target effect [33][34]. One of the new variants of the CRISPR/Cas9 method—prime editing—enables the most precise changes in the genome, limited to one base pair, minimizing the possibility of off-target mutations [34][35][35,36].

Theoretically, the CRISPR/Cas9 system can be applied to any DNA sequence using engineered gRNA. However, the specificity of the action of Cas9 nuclease depends on the 2–8 nucleotide PAM sequence located immediately downstream of the target sequence [1][2]. The identified PAM sequences differ among Cas9 protein orthologs (Table 1). The PAM sequence restricts the target site selection for the CRISPR/Cas9 system. The PAM sequences NGG and NAG occur in the genome on average once every eight nucleotides, while the PAM sequence NGGNG occurs once every 32 nucleotides, and NNAGAAW occurs once every 256 nucleotides. Therefore, the length of the PAM sequence affects the specificity of the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Mutations outside the target site for a system requiring a short PAM arise more frequently than when using a CRISPR/Cas9 system dependent on longer PAM sequences [9][36][10,37].

Table 1. Examples of Cas9 protein orthologs.

Ortholog | Host Organism | PAM Sequence (5′→3′) | References | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

NmeCas9 | Neisseria meningitidis | NNNNG(A/C)TT |

[37] |

[38] |

|||||||

SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT or NNNRRT |

[38] |

[39] |

|||||||

St1Cas9 | Streptococcus thermophilus | NNAGAA or NNAGAAW |

[39] |

[40] |

|||||||

ScCas9 | Streptococcus canis | NNG |

[40] |

[41] |

|||||||

CjCas9 | Campylobacter jejuni | NNNNACA |

[41] |

[42] |

|||||||

FnCas9 | Francisella novicida | YG |

[42] |

[43] |

|||||||

St2Cas9 | Streptococcus thermophilus | NGGNG |

[43] |

[44] |

The existence of PAM sequence constraints is a major limiting factor in research using the CRISPR/Cas system. There are systems based on non-Cas9 nuclease. One of them is Cas12a (formerly known as Cpf1). It needs a single RNA molecule (crRNA) to function, not a crRNA:tracrRNA hybrid like Cas9 nuclease. Cas12a recognizes the T-rich PAM sequence, which is a great advantage as it could be used in places in the genome where it is not possible to design a cleavage with the standard Cas9 system. Moreover, it cleaves DNA via a staggered DNA DSB [44][45][45,46]. There is also a Cas12b nuclease, but its use is challenging due to the high temperature requirements [46][47].

It has also been proven that there are additional limiting factors in the use of the CRISPR/Cas system for genome modification. One of them is p53-dependent toxicity, which was noted in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) after indel, obtaining efficiency greater than 80%. This process should be monitored when using the CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome modification [47][48]. In addition, repair of DSBs after CRISPR/Cas9 use may result in large inversions and deletions (about 10 kb), not just small indel mutations [48][49]. Repair may also result in the formation of chromosomal translocations [19][20] or in loss of one or both chromosomal arms [49][50]. Systems based on inactivated/dead Cas9 nuclease show lower genotoxicity due to lack of nuclease activity and non-formation of DSBs; however, their use depends on the purpose of the research, as their effects may be short-term. However, the CRISPR-STOP and iSTOP technology results in the permanent inactivation of the gene by introducing the stop codons into the modified sequence [50][51].