Cultural Dimensions of Climate means that climatic events express the dynamics of the Earth’s oceans and atmosphere, but are profoundly personal and social in their impacts, representation and comprehension. Knowledge of the climate has multiple scales and dimensions that intersect in our experience of the climate. The climate is objective and subjective, scientific and cultural, local and global, and personal and political. These divergent dimensions of the climate frame the philosophical and cultural challenges of a dynamic climate. Drawing on research into the adaptation in Australia’s Murray Darling Basin, this paper outlines the significance of understanding the cultural dimensions of the changing climate.

- critical realism

- cultural adaptation

- custodial ethics

- socio-natural hybrids

- knowledge politics

- climate subjectivities

- climate co-production

1. Introduction

Each time we take in information about the weather from forecasts delivered via television, radio, the press, books, posters or the Internet, we are receiving the product of an extraordinary cooperative, international effort to understand the Earth’s systems and their dynamics, which frame our understanding of the world [1]. A global network of instrumentation observations, technologies, models, theories, data and communications involving people, technologies, skills and knowhow produce these forecasts, contributing to our comprehension of the planetary systems at the local and global scale [2]. When we use these forecasts to make decisions about our work and life, we are processing and acting on this information, responding to nature (as in natural phenomena) and the culturally constructed system of representing and understanding nature [3]. We are part of enormous cultural and scientific information processing systems that construct the knowing and governing of the climate via technological, scientific and social networks [4].

We argue that knowledge of the climate has multiple scales and dimensions. The climate is objective and subjective, scientific and cultural, local and global and personal and political. This entry explores these contextual and cultural dimensions of the climate. It seeks to expand the scope of definitions of ‘the climate’ and examine some of the philosophical and cultural challenges posed by a dynamic climate. The central idea is that climate change is an objective fact and a subjective reality that frames our understanding and experience of the world.

The question central to this investigation is: how do the cultural dimensions of the climate, including the subjectivities involved, shape our understanding of climate change?

The opening up of debate around these questions is not arguing that climate change is entirely relative, or merely a matter of belief, rather than an objective fact about the Earth’s systems changing. Instead, it is querying whether greater recognition of the co-existence of subjectivity and objectivity in meaning-making would enhance commitment to actions that build on the scientific understanding of the rapidly changing climate.

This entry builds on the idea that the natural and social worlds coexist and co-produce reality, through forming socio-natural hybrids [5]. These hybrids combine social and natural phenomena. Understanding these hybrids requires bringing together the social and natural sciences. Furthermore, it requires recognising the rituals and culture of science and scientific endeavours that influence society by contributing to the construction of meaning [5]. The global phenomenon of climate change illustrates the complex, evolving nature of these hybrids [6][7]. This entry portrays climate and climate adaptation as socio-natural hybrids—those complex systems that link geophysical and socio-political processes in ways which cannot be neatly separated [5][7].

We argues that climate science contributes to the cultural construction of meaning around climate issues [1][7] and that understanding of climate science occurs within relational networks that are profoundly social and political [4]. Furthermore, people’s understanding of climate change depends on their social networks and contexts [4][6]. Theoretical concepts of the climate permeate our cultural understandings and lived experience of the modern world. Therefore, the climatic conditions we understand and experience are culturally co-constructed with the natural phenomena of the weather. How this cultural construction of the climate evolves is a worthy subject of scholarship [1][2][4][7].

2. The Cultural Construction of Climate—‘Climate Normal’ and Climate Change

Preceding sections outlined why we need to recognise the climate’s materialities and agency. This section proposes that we must recognise the cultural construction of climate normal and climate change. In addition to being a geophysical phenomenon, climate change is also deeply cultural, in the sense that both climate change and ‘climate normal’ are culturally constructed. Hulme et al. [2] argued that the whole framing of climate change implies a reference to ‘climate normal’, itself constructed via a cooperative global scientific effort. This effort involves the measurements and statistical manipulations used to derive the averages that define ‘normal’ climatic conditions. The notions of the ‘climate’ embeds these expectations of normality, and therefore, of change from the normal conditions [2]

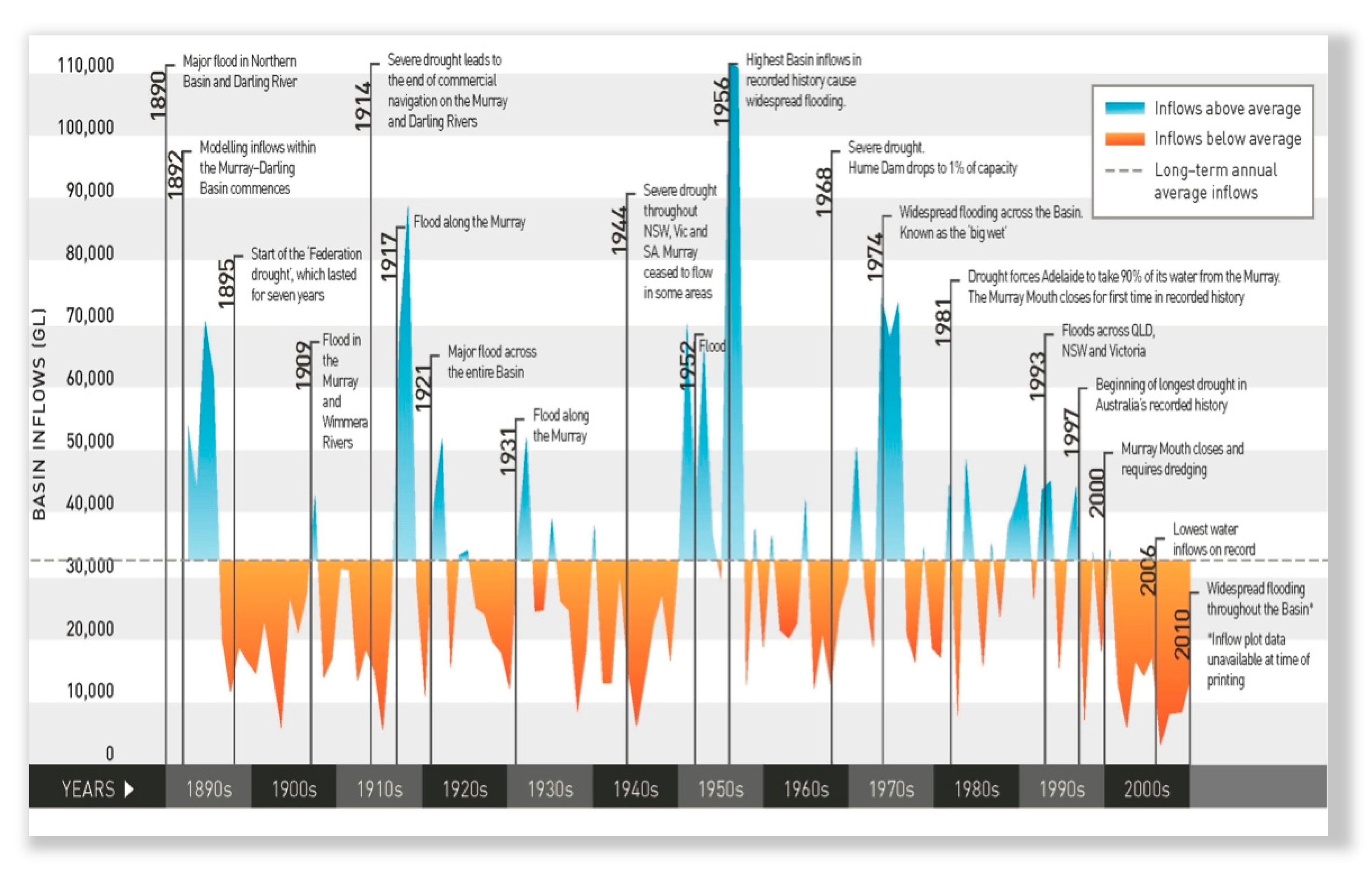

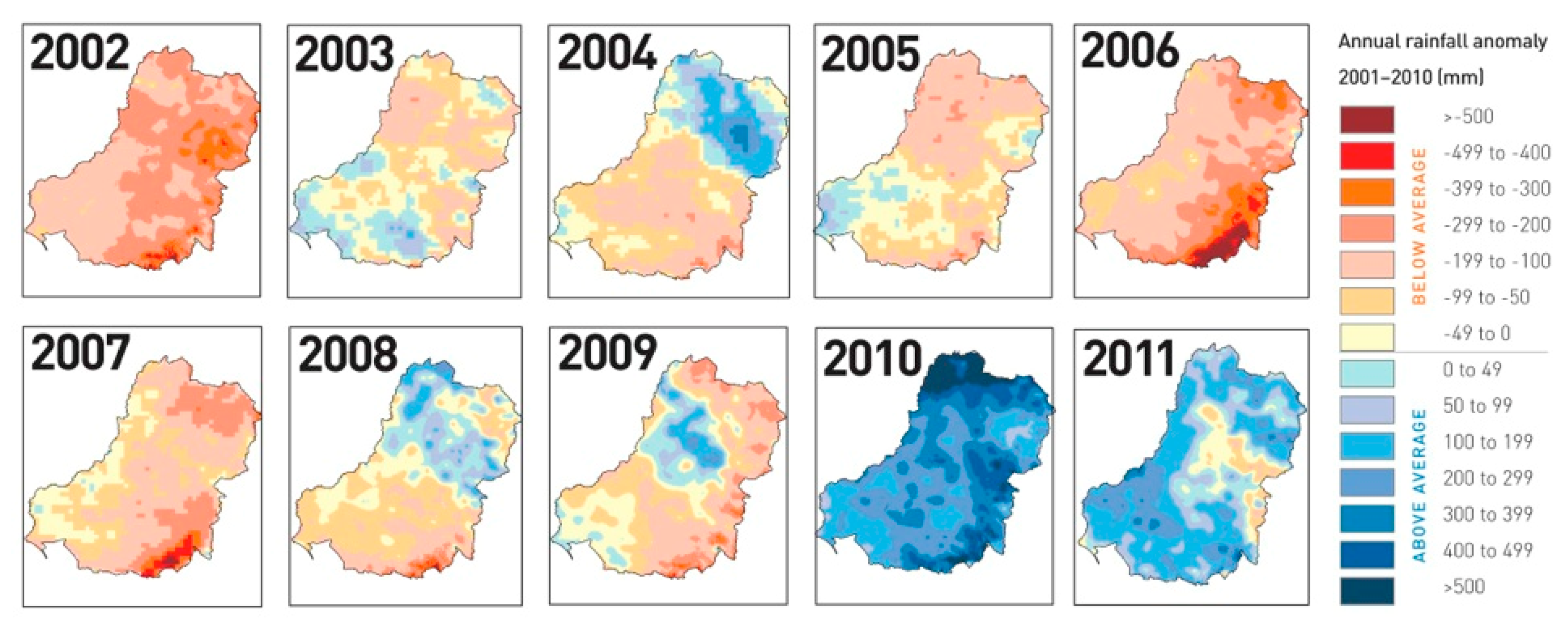

When we apply the expectation of a standard or predictable climate, the deviations from normal conditions are referred to as extreme events and ‘anomalies’, implying the abnormality of non-average conditions (see Figure 2Figure 1). However, in southern Australia, conditions conforming to the “average” conditions occur coincidentally due to fundamental drivers of the oceans’ climatic conditions that bring oscillating wet–dry cycles [8][9]. Reconstructions of the hydro-climate beyond the instrumental records, using climate proxies, demonstrate that recurrent droughts, punctuated by floods, typify the climate patterns over centuries and millennia [10]. Furthermore, these proxy records indicate that extreme flood events and long periods of drought are distinct and typical parts of the historical record [10].

Policy ‘artefacts’—posters, brochures, websites and reports intended to inform, educate and instruct ‘the public’—offer potential sources for research exploring the cultural construction of climate and how official documents represent climatic conditions [11][12]. For example, the MDBA’s [13][14] (2011a and 2011b) posters on river inflows (Figure 2Figure 1) and the Millennium Drought’s rainfall anomalies (Figure 3Figure 2) reveal ways the cultural construction of ‘climate normal’ are reinforced and refracted by countless representations of nature [3]. With their references to averages and deviations from them, these posters offer evidence that averages conditions are abnormal due to the climate oscillating through extended cycles of drought–flood [8][9][10]. These representations of the climate demonstrate how concepts of ‘climate normal’ are reinforced through posters and other information sources and used to justify policies that attempt to drought-proof irrigated agriculture in the basin [15][11].

The two posters reproduced above are examples of the abundance of information that conditions our comprehension of the climate. These representations embed concepts of nature and its averaged conditions [3], and that define variations or changes arising in contrast to these averages. Averages are not just used to represent the climate, but are also the basis of water resource planning in the MDB, where averages of available water resources were projected forward to 2030 by the statutory instrument of the Basin Plan, despite strong scientific evidence of a drying climate [16][17][18].

The Millennium Drought (1996–2010) had severe impacts on riverine ecosystems, industries and communities throughout the Basin [8]. The drought was defined as a national crisis that triggered major reforms [8]. However, while there is much evidence for climate change contributing to the drying of the MDB, the MDBA relied on the 114-year climate history (1895–2009) for the Basin Plan modelling [16]. Therefore, the MDB Plan relies on the historical climate during the instrumental period, as the basis for future projections. This failure to adequately incorporate climate science into responses to climate risks has been described by a formal judicial inquiry as incomprehensible maladministration [17]. However, this choice may also indicate a deep-seated yearning from settler–colonial water governance institutions for a safe, reliable, ‘normal’ climate, one that delivers predictable water supplies to the intensively irrigated agriculture that has arisen in the Basin in a little over a century of re-engineering the rivers for that purpose.

In contrast to irrigated agriculture, the ecosystems of the MDB have evolved to be superbly adapted to the boom–bust, flood–drought cycles driven by the southern continent’s highly variable climate [8][9] (see also Figure 2Figure 1 and Figure 3Figure 2). However, these ecosystems cannot adjust to the impacts of over extraction of water for irrigation [19][20]. A deep reluctance to accept the flood–drought cycle is apparent in the history of Australia’s policies [21][22], many of which focused on drought proofing—ambitious engineering schemes intended to overcome the continent’s variability [15][11][23]. A similar type of reluctance to accept the reality of climate change is driving maladaptive policy formulation, including an unattainable search for scientific certainty, and the conflation of climate variability with climate change in many official documents [17].

By bringing a cultural perspective to interpreting the MDB reforms, this paper argues that the hydro-climatic conditions of the Basin are coproduced by culture. These variable conditions are a combination of the natural or physical phenomena, and the way water and rivers are defined, understood and governed. Settler–colonial Australia has increasingly defined water as an extractable resource that can be exchanged in a market economy, to the detriment of a range of other aspects of the value of rivers [19][24]. To protect these other aspects of value and to become genuinely inclusive of Indigenous People’s perspectives and relationships will require significant renegotiations on the fundamentals principles and practices of how water is understood and governed in modern Australia [24][25][26][27]. Developing models of co-governance and recognising Indigenous wisdom, experience and connections provides important opportunities for recalibrating the nation’s relationships to its rivers [25][26][27]. As a nation, Australia can only do this through integrating natural and cultural heritage conservation, developing appropriate models of economic development and recognising the long and proud history of Indigenous governance of rivers and their catchments [26][27]. Incorporating long-term cultural perspectives provides significant opportunities for treating rivers, and their peoples, with greater respect and reverence [26][27].

Figure 21. River inflows for the Murray Darling Basin [13].

Figure 21. River inflows for the Murray Darling Basin [13].

Figure 32. Rainfall “anomalies” 2002 to 2011 in the MDB [14].

Figure 32. Rainfall “anomalies” 2002 to 2011 in the MDB [14].

References

- Hulme, M. The conquering of climate: Discourses of fear and their dissolution. Geogr. J. 2008, 174, 5–16.

- Hulme, M.; Dessai, S.; Lorenzoni, I.; Donald, R.; Nelson, D.R. Unstable climates: Exploring the statistical and social constructions of ‘normal’ climate. Geoforum 2008, 40, 197–206.

- Castree, N. Making Sense of Nature; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2014.

- Cunningham, R.; Jacobs, B.; Measham, T.G. Uncovering Engagement Networks for Adaptation in Three Regional Communities: Empirical Examples from New South Wales, Australia. Climate 2021, 9, 21.

- Latour, B. We Have Never Been Modern; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993.

- Ison, R.; Alexandra, J.; Wallis, P. Governing in the Anthropocene: Are there cyber-systemic antidotes to the malaise of modern governance? Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1209–1223.

- Latour, B. Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2018.

- Van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Beck, H.E.; Crosbie, R.S.; de Jeu, R.A.M.; Liu, Y.Y.; Podger, G.M.; Timbal, B.; Viney, N.R. The Millennium Drought in southeast Australia (2001–2009): Natural and human causes and implications for water resources, ecosystems, economy, and society. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49.

- Kiem, A.S.; Verdon-Kidd, D.C. The importance of understanding drivers of hydroclimatic variability for robust flood risk planning in the coastal zone. Australas. J. Water Resour. 2013, 17, 126–134.

- Gallant, A.J.E.; Gergis, J. An experimental streamflow reconstruction for the River Murray, Australia, 1783–1988. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47, W00G04.

- Arthur, J.M. The Default Country: A Lexical Cartography of Twentieth-Century Australia; UNSW Press: Sydney, Australia, 2003.

- Cathcart, M. The Water Dreamers—The Remarkable History of Our Dry Continent; Text: Melbourne, Australia, 2009.

- MDBA. Annual Rainfall Anomalies 2002 to 2011; MDBA: Canberra, Australia, 2011.

- MDBA. Basin inflows 1892–2010; MDBA: Canberra, Australia, 2011.

- Gibbs, L. Just add water: Colonisation, water governance, and the Australian inland. Environ. Plan. A 2009, 41, 2964–2983.

- Alexandra, J. Navigating the Anthropocene’s rivers of risk—climatic change and science-policy dilemmas in Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin. Clim. Chang. 2021, 165, 1–21.

- Alexandra, J. The science and politics of climate risk assessment in Australia’s Murray Darling Basin. Env. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 17–27.

- Alexandra, J. Evolving Governance and Contested Water Reforms in Australia’s Murray Darling Basin. Water 2018, 10, 113.

- Jackson, S.; Head, L. Australia’s mass fish kills as a crisis of modern water: Understanding hydrological change in the Murray-Darling Basin. Geoforum 2020, 109, 44–56.

- Pittock, J.; Finlayson, C.M. Australia’s Murray—Darling Basin: Freshwater ecosystem conservation options in an era of climate change. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2011, 62, 232–243.

- Heathcote, R.L. Drought in Australia: A Problem of Perception. Geogr. Rev. 1969, 59, 175.

- Heathcote, R.L. Drought in Australia: Still a problem of perception? Geo J. 1988, 16, 387–397.

- Lines, J. Taming the Great South Land: A History of the Conquest of Nature in Australia; Penguin: Melbourne, Australia, 1994.

- Hartwig, L.; Jackson, S.; Osborne, N. Trends in Aboriginal water ownership in New South Wales, Australia: The continuities between colonial and neoliberal forms of dispossession. Land Use Policy 2020.

- Moggridge, B.J.; Thompson, R.M. Cultural value of water and western water management: An Australian indigenous perspective. Australas. J. Water Resour. 2021.

- River of Life; Martuwarra; Poelina, A.; Alexandra, J.; Samnakay, N. A conservation and management plan for the National Heritage listed Fitzroy River Catchment Estate (No. 1). Martuwarra Fitzroy River Council, Nulungu Research Institute. Univ. Notre Dame Aust. 2020.

- Poelina, A.; Taylor, K.S.; Perdrisat, I. Martuwarra Fitzroy River Council: An Indigenous cultural approach to collaborative water governance. Australas. J. Env. Manag. 2019, 26, 236–254.