A consensus definition of physical restraint describes it as "any action or procedure that prevents a person’s free body movement to a position of choice and/or normal access to his/her body by the use of any method, attached or adjacent to a person’s body that he/she cannot control or remove easily." (Bleijleves, Gulpers, Cpezuti, et. al., 2013). Definitions for chemical restraints in long-term care have included ‘medication classes’, e.g. psychotropics, hypnotics, etc. however, without a consensus definition of which drug classes are considered to be chemical restraint, there is no consistency.

- bedrail

- belt

- mitt

- surveillance

- lock

- gerichair

- posey chair

- aged care facility

- nursing home

1. Introduction

Frequent use of physical and chemical restraint remains a concern in long-term care facilities internationally [1][2][3][4]. Use of restraint has been justified on the basis of preventing harm to the individual [5][6][7][8] or to others [5][8]. However, adverse consequences of physical restraint include injury, lower cognitive performance, lower performance in activities of daily living (ADLs), higher walking dependence, increased falls, pressure injuries, urinary and faecal incontinence, and death [9][10][11]. Chemical restraint use can lead to decrease in functional and cognitive performance, falls and fractures, excess sedation, and respiratory depression [12][13][14]. Prescribing of antipsychotics has been linked to an increased risk of stroke and mortality [15][16]. Consequently, there have been a range of clinical and policy initiatives over past decades to minimise use of restraint [7][17][18][19][20].

There is considerable variability in rates of physical and chemical restraint between and within countries [21]. Understanding and comparing the impact of different policies and strategies to minimise physical and chemical restraint requires both consistent definitions and measurement. An international consensus definition of ‘physical restraints’ for research was published in 2016. Physical restraint was defined as “any action or procedure that prevents a person’s free body movement to a position of choice and/or normal access to his/her body by the use of any method, attached or adjacent to a person’s body that he/she cannot control or remove easily.” [22]. However, not all research over the past two decades has employed this definition. This may lead to an under or over-estimation of physical restraint prevalence depending on whether the definitions these studies employed had included more or less of the different “restraint” practices as indicated by the international consensus definition of physical restraint. Moreover, it is unclear how well measurement approaches for physical restraints align with both the consensus definition or the definition adopted within the individual studies. Research on chemical restraint is also limited by the absence of a published international consensus definition. Psychotropic medications (e.g., antipsychotics) have approved clinical indications and it is often unclear in prevalence studies what proportion of psychotropic prescribing reflects an intent to restrain [23]. Furthermore, a range of medications have been implicated in restraint, with psychotropic medications including both primary sedatives (benzodiazepines) and medications with sedation as a prominent side-effect (e.g., sedating antidepressants, opioids) [24].

Many studies do not explicitly define physical or chemical restraint. Without clarity on what is being defined as restraint we cannot compare results between studies, we cannot be sure if factors identified as being associated with higher rates of restraint are truly so, and we cannot know if interventions and policies designed to reduce use of restraint actually result in claimed outcomes. Consequently, health professionals will be unable to take actions to reduce use of restraint that are based upon robust evidence, older people will receive care where appropriate monitoring and minimisation of restraint cannot be achieved, and society will struggle to fully appreciate the nature and scale of problems created by use of restraint.

2. Physical and Chemical Restraint in Long-Term Care

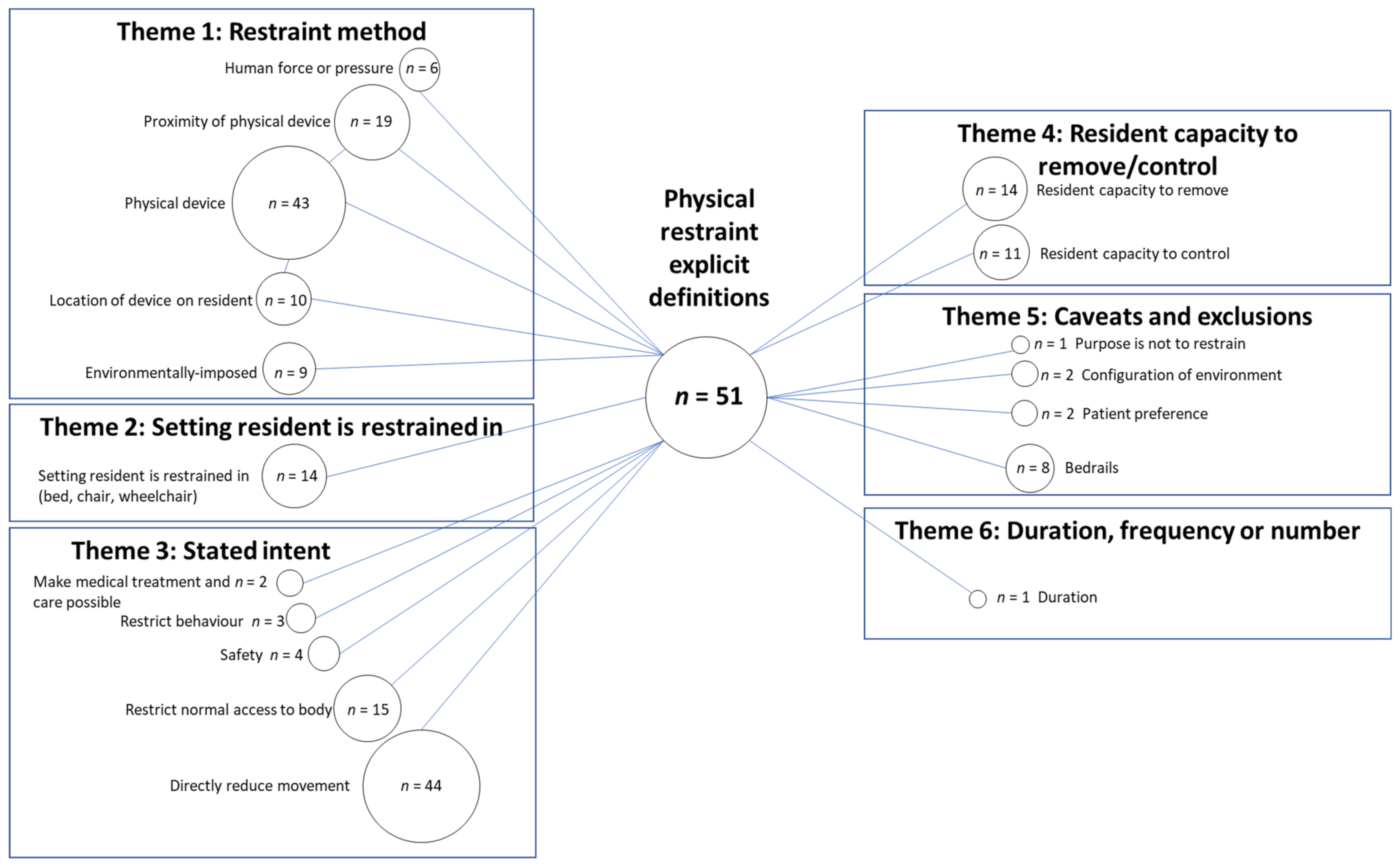

Definitions of physical restraint have been highly variable in the research describing the prevalence of physical restraint or interventions targeting restraint reduction in long-term care setting. This was comparatively more variable than the definitions of chemical restraint used in the included studies, although substantially fewer studies were identified reporting chemical restraint. Each definition has encompassed various themes relating to aspects of restraint use, with different codes and frequencies of codes within each theme. In particular, the themes that emerged for physical restraint explicit definitions mismatched those for implicit definitions in which “consent and resistance” was only captured in the implicit definitions. In addition, although some studies of physical or chemical restraint reported the reliability of their measurement tools, the majority did not report any reliability or validity data raising the question of potential inaccuracy in their measurement of restraints.

The variable explicit definitions of physical restraint was highlighted by the variety of bubble sizes in Figure 2Figure 1. It is evident that whether some or all of the themes identified in definitions were used will affect the measurement of restraint. In addition, the specifications for a minimum duration that is required for a resident to be considered to have been restrained, the frequency with which a restraint method is applied and whether caveats apply will also affect the measurement of restraint.

Some of the themes identified in the definitions used in the included studies are missing in the international consensus definition of physical restraints. The consensus definition states that “Physical restraint is defined as any action or procedure that prevents a person’s free body movement to a position of choice and/or normal access to his/her body by the use of any method, attached or adjacent to a person’s body that he/she cannot control or remove easily.” [22] While this definition does encompass the domains of ‘restraint method’, ‘stated intent’, and ‘resident capacity to remove/control’, this definition does not include reference to the ‘setting resident is restrained in’, ‘duration, frequency or number’, ‘consent and resistance’ or any ‘caveats and exclusions’. This will have an impact on measurement and is likely to produce different results to studies using these elements in their definitions.

Study authors generally stated that physical restraint should be defined as including the six themes highlighted in Figure 2Figure 1, while what was measured generally excluded ‘resident capacity to remove/control’ (with the exception of three studies), and the ‘stated intent’. Many studies were unable to be included in the analysis of reporting of results due to the lack of detail for what results reflected. These results often referred to the physical restraint outcome data collectively as “physical restraint” with an accompanying percentage of participants reported as being restrained. This type of reporting does not inform the reader about what devices were applied or how frequently each device was being applied to residents. Reporting of results that did report some detail generally omitted the themes of ‘stated intent’, ‘duration, frequency or number’, ‘consent and resistance’ and ‘resident capacity to remove/control’. Not only were these findings apparent across this field of study, this mismatch between definitions and data collection approaches and results was also present within individual papers. For example, one study defined physical restraint to be “Any device, material, or equipment attached to or near the residents’ body which cannot be controlled easily or removed by the person and which deliberately prevents or is deliberately intended to prevent free body movement to a position of choice” (encompassing the themes of ‘restraint method’, ‘stated intent’, ‘resident capacity to remove/control’) yet their measurement approach only included “Data on the prevalence of physical restraint use… at 3 time points during 1 day… residents with a physical restraint at 1 or more of the 3 time points were counted as having a restraint” (encompassing the theme of ‘duration, frequency or number’) [25]. This mismatch indicates that the internal face and content validity of measurement approaches within this field can be seriously questioned, as measurement approaches used by researchers do not conform to, or omit, key elements of the definitions of restraint that they themselves have provided. Whether frequency and duration of restraint application are relevant information for a definition of physical restraint is also questionable. The consensus definition does not include frequency or duration elements. It might, however, be useful for outcome measures to reflect intensity of restraint use.

One commonly reported element of explicit definitions of physical restraint is the inability, or relative lack of ease with which a resident can remove or control their physical restraint. However, this element is rarely measured within studies. Only one study directly observed the ability of a sample of residents to remove their restraint as part of the outcome measure, “If a resident had any device that could potentially limit movement, he or she was asked to release this device prior to standing and given graduated prompts to do so”, results were then reported as having been “corrected for ability to release” [26]. While not all of the definitions within this review included the inability of a resident to remove or control the restraint as a defining condition, the consensus review does include reference to this. If future studies are to apply the consensus definition, then this ability should be included as part of the outcome measure for physical restraint.

Most explicit definitions of physical restraint included a statement regarding the intent of the restraint, however, only a limited number took this into account in their measurement approach and few studies reported results for these data. This begs the question of why restraints were being applied in the studies. The consensus definition states that the restraint ‘prevents a person’s free body movement to a position of choice and/or normal access to his/her body’. There are a number of conditions described in some of the reviewed studies that would be considered to be outside this definition. For example, an individual locked in their room might be considered to have ‘free body movement to a position of choice’, however, they may not be free to move to a location of choice as they are unable to leave their room.

The topic of ‘consent’ was not raised in explicit definitions of physical restraint. This topic arose from within outcome data collection approaches and reporting of results, for example, bedrails without the patients consent [27]. This leads to the question of whether the resident consenting to the application of a restraint method disqualifies it as a physical restraint and whether outcome measures and results for physical restraint should reflect this.

A range of outcome data collection approaches were applied across the included studies with only inter-rater reliability having been tested in a limited number of studies to reveal moderate to high reliability. RAI-MDS Version 2 was the most commonly applied outcome measure and does not take into account many of the codes and themes identified in this thematic analysis. Specifically, there is no assessment of environmentally imposed physical restraints, human force or pressure, resident capacity to remove or control the restraint, what the intent of the restraint is or whether resident knowledge or consent has been provided. It has been shown that nursing staff often use less traditional methods of restraint such as removing the resident’s mobility device, keeping the resident inadequately clothed, and even residents feeling so unsafe that they voluntarily lock themselves in their rooms [28]. One study included in this review described how wheelchairs might be classified as a physical restraint if the foot-plates were elevated, “pedals were considered “Elevated” only if they were moved up from a 90° angle perpendicular to the floor” [26]. The RAI-MDS includes a very limited number of the potential methods for physical restraining residents that have been reported in the literature.

In comparison to the physical restraint consensus definition, there is a relative absence of a clear definition of chemical restraint in long-term care. Definitions for chemical restraints included ‘medication classes’, e.g. psychotropics, hypnotics, etc. however, without a consensus definition of which drug classes are considered to be chemical restraint, there is no consistency. Some definitions described the intent of these medications, including to control behaviour or for organisational convenience. Given that these medications often have approved clinical indications then reason for prescription or use is important to consider in defining chemical restraint.

The relative lack of research that clearly identified “chemical restraint” is an important finding given the increasing level of debate about high rates of psychotropic medication use. The intent to ‘control behaviour’ was a theme in the definition of chemical restraint. However, most data sources used in pharmacoepidemiological studies (e.g., prescribing data, pharmacy dispensing data, medication administration charts) do not record the intent of medical practitioners, pharmacists or nurses when prescribing, dispensing or administering psychotropic medications. The term “potentially inappropriate medication use” is often used by researchers when applying explicit or implicit measures of medication appropriateness (e.g., American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria [29], STOPP/START criteria [30], Medication Appropriateness Index [31]), although potentially inappropriate psychotropic medication use is not necessarily synonymous with chemical restraint. Potentially inappropriate medication use is often defined as use that is associated with more risks than benefits, particularly when safer alternatives exist [32]. This may include use of a medication for an approved indication but at a dose or for a duration that predisposes to adverse drug events. Establishing a clear and measurable definition of chemical restraint will be important moving forward given the recent calls for greater transparency and accountability associated with prescribing, dispensing and administration of psychotropic medications.

Figure 21. Codes and themes present within explicit definitions of physical restraint. n = number of explicit definitions for which this code was identified as being a part of the definition.

References

- Estévez-Guerra, G.J.; Fariña-López, E.; Núñez-González, E.; Gandoy-Crego, M.; Calvo-Francés, F.; Capezuti, E.A. The use of physical restraints in long-term care in Spain: A multi-center cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 29.

- Huang, H.C.; Huang, Y.T.; Lin, K.C.; Kuo, Y.F. Risk factors associated with physical restraints in residential aged care facilities: A community-based epidemiological survey in Taiwan. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 70, 130–143.

- Heinze, C.; Dassen, T.; Grittner, U. Use of physical restraints in nursing homes and hospitals and related factors: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 21, 1033–1040.

- Chiba, Y.; Yamamoto-Mitani, N.; Kawasaki, M. A national survey of the use of physical restraint in long-term care hospitals in Japan. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 1314–1326.

- Bowblis, J.R.; Crystal, S.; Intrator, O.; Lucas, J.A. Response to regulatory stringency: The case of antipsychotic medication use in nursing homes. Health Econ. 2012, 21, 977–993.

- Halfens, R.J.; Meesterberends, E.; Van Nie-Visser, N.C.; Lohrmann, C.; Schönherr, S.; Meijers, J.M.; Hahn, S.; Vangelooven, C.; Schols, J.M. International prevalence measurement of care problems: Results. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, e5–e17.

- Testad, I.; Ballard, C.; Bronnick, K.; Aarsland, D. The effect of staff training on agitation and use of restraint in nursing home residents with dementia: A single-blind, randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 80–86.

- Gunawardena, R.; Smithard, D.G. The Attitudes towards the Use of Restraint and Restrictive Intervention Amongst Healthcare Staff on Acute Medical and Frailty Wards—A Brief Literature Review. Geriatrics 2019, 4, 50.

- Evans, D.; Wood, J.; Lambert, L. Patient injury and physical restraint devices: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 41, 274–282.

- Hofmann, H.; Hahn, S. Characteristics of nursing home residents and physical restraint: A systematic literature review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 3012–3024.

- Engberg, J.; Castle, N.G.; McCaffrey, D. Physical restraint initiation in nursing homes and subsequent resident health. Gerontologist 2008, 48, 442–452.

- Foebel, A.D.; Onder, G.; Finne-Soveri, H.; Lukas, A.; Denkinger, M.D.; Carfi, A.; Vetrano, D.L.; Brandi, V.; Bernabei, R.; Liperoti, R. Physical Restraint and Antipsychotic Medication Use Among Nursing Home Residents With Dementia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 184.e9–184.e14.

- Muir-Cochrane, E.; Oster, C.; Gerace, A.; Dawson, S.; Damarell, R.; Grimmer, K. The effectiveness of chemical restraint in managing acute agitation and aggression: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 110–126.

- Hill, K.D.; Wee, R. Psychotropic Drug-Induced Falls in Older People. Drugs Aging 2012, 29, 15–30.

- Zivkovic, S.; Koh, C.H.; Kaza, N.; Jackson, C.A. Antipsychotic drug use and risk of stroke and myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 1–14.

- Ralph, S.J.; Espinet, A.J. Increased All-Cause Mortality by Antipsychotic Drugs: Updated Review and Meta-Analysis in Dementia and General Mental Health Care. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2018, 2, 1–26.

- Koczy, P.; Becker, C.; Rapp, K.; Klie, T.; Beische, D.; Büchele, G.; Kleiner, A.; Guerra, V.; Rissmann, U.; Kurrle, S.; et al. Effectiveness of a Multifactorial Intervention to Reduce Physical Restraints in Nursing Home Residents. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 333–339.

- Pellfolk, T.J.-E.; Gustafson, Y.; Bucht, G.; Karlsson, S. Effects of a Restraint Minimization Program on Staff Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice: A Cluster Randomized Trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 62–69.

- Testad, I.; Mekki, T.E.; Forland, O.; Oye, C.; Tveit, E.M.; Jacobsen, F.; Kirkevold, Ø. Modeling and evaluating evidence-based continuing ed-ucation program in nursing home dementia care (MEDCED)—Training of care home staff to reduce use of restraint in care home residents with dementia. A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 24–32.

- Gulpers, M.J.; Bleijlevens, M.H.; Capezuti, E.; Van Rossum, E.; Ambergen, T.; Hamers, J.P. Preventing belt restraint use in newly admitted residents in nursing homes: A quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 1473–1479.

- Lee, D.-C.A.; Robins, L.M.; Bell, J.S.; Srikanth, V.; Möhler, R.; Hill, K.D.; Griffiths, D.; Haines, T.P. Prevalence and variability in use of physical and chemical restraints in residential aged care facilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 117, 103856.

- Bleijlevens, M.H.C.; Wagner, L.M.; Capezuti, E.; Hamers, J.P.H. Physical Restraints: Consensus of a Research Definition Using a Modified Delphi Technique. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 2307–2310.

- Muñiz, R.; Pérez-Wehbe, A.I.; Couto, F.; Pérez, M.; Ramírez, N.; López, A.; Rodríguez, J.; Usieto, T.; Lavin, L.; Rigueira, A.; et al. The “CHROME criteria”: Tool to optimize and audit prescription quality of psychotropic medications in institutionalized people with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 32, 315–324.

- Taipale, H.T.; Bell, J.S.; Soini, H.; Pitkälä, K.H. Sedative load and mortality among residents of long-term care facilities: A prospective cohort study. Drugs Aging 2009, 26, 871–881.

- Köpke, S.; Mühlhauser, I.; Gerlach, A.; Haut, A.; Haastert, B.; Möhler, R.; Meyer, G. Effect of a guideline-based multicomponent inter-vention on use of physical restraints in nursing homes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2012, 307, 2177–2184.

- Schnelle, J.F.; Bates-Jensen, B.M.; Levy-Storms, L.; Grbic, V.; Yoshii, J.; Cadogan, M.; Simmons, S.F. The Minimum Data Set Prevalence of Re-straint Quality Indicator: Does It Reflect Differences in Care? Gerontologist 2004, 44, 245–255.

- Kirkevold, O.; Engedal, K. Prevalence of patients subjected to constraint in Norwegian nursing homes. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2004, 18, 281–286.

- Saarnio, R.; Isola, A. Use of physical restraint in institutional elderly care in Finland: Perspectives of patients and their family members. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2009, 2, 276–286.

- American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694.

- O’Mahony, D.; O’Sullivan, D.; Byrne, S.; O’Connor, M.N.; Ryan, C.; Gallagher, P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 2. Age Ageing 2015, 44, 213–218.

- Hanlon, J.T.; Schmader, K.E. The medication appropriateness index at 20: Where it started, where it has been, and where it may be going. Drugs Aging 2013, 30, 893–900.

- Hamilton, H.J.; Gallagher, P.F.; O’Mahony, D. Inappropriate prescribing and adverse drug events in older people. BMC Geriatr. 2009, 9, 5.