Serine Peptidase Inhibitor Kazal Type 1 (SPINK1) is a secreted protein known as a protease inhibitor of trypsin in the pancreas. However, emerging evidence shows its function in promoting cancer progression in various types of cancer. SPINK1 modulated tumor malignancies and induced the activation of the downstream signaling of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in cancer cells, due to the structural similarity with epidermal growth factor (EGF). The discoverable SPINK1 somatic mutations, expressional signatures, and prognostic significances in various types of cancer have attracted attention as a cancer biomarker in clinical applications.

- SPINK1

- prognosis

- carcinogenesis

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

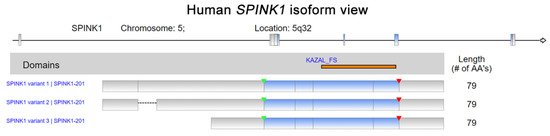

Serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal type I (SPINK1) was first discovered in bovine pancreas extracts by Kazal et al., and the molecule was designated a pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI) [1]. SPINK1, which is also known as tumor-associated trypsin inhibitor (TATI), was further isolated from the urine of ovarian cancer patients by another research group [2]. SPINK1 and TATI were later characterized as identical molecules [3]. SPINK1 was first demonstrated to be released by acinar cells in the exocrine pancreas into the pancreatic duct and to interact with trypsin, inhibiting its activity both intracellularly and extracellularly [1]. The human SPINK1 gene encodes an mRNA that is spliced into three transcript variants, which can be translated into a 79-amino acid peptide, including a 23-amino-acid signal peptide (Figure 1) [4,5][4][5]. In addition, the in silico prediction and precise splicing outcomes of the pathogenic SPINK1 intronic variants have been reported [6]. Emerging evidence has demonstrated the relationship between SPINK1 and cancer progression [7,8][7][8]. SPINK1, as a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factor, is produced in human stromal cells after genotoxic treatment because of DNA damage elicited by NF-κB and C/EBP signaling activation [9]. Interestingly, a SPINK1 interaction with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in rat liver hepatocyte line of BRL-3A in vitro has been indicated [10]. Additionally, an immunoreactivity study of colorectal cancer showed a positive Pearson’s correlation between SPINK1 and EGFR intensity [11]. Moreover, SPINK1 reprograms the expression profile of prostate cancer cells, leading to prominent epithelial–endothelial transition (EET), a phenotypic switch mediated by EGFR signaling [9]. Hence, the interaction of SPINK1 with EGFR has attracted attention for its potentially pivotal biological functions, especially in modulating cancer progression. Functionally, the SPINK1-driven biological effect induced by EGFR signaling was reported in ovarian cells [12]. In pancreatic cancer cell lines, SPINK1 was coprecipitated with EGFR in an immunoprecipitation experiment and trigger cancer cell proliferation via activating EGFR downstream signaling [13]. In prostate cancer, EGFR was found to mediate SPINK1′s biological function when triggering the epithelial–mesenchymal transition [14].

Human Serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal type I (

) isoform view. The data were retrieved and analyzed from Refseq. The matching protein domains in various RNA isoforms are marked and located in orange. The start of transcription and position of a stop codon are indicated by green and red arrowheads, respectively.

Current evidence emphasizes the urgent need to clarify the prognostic value of SPINK1 and unravel the SPINK1-dependent molecular mechanisms involved in human cancers. In this review article, SPINK1 expression is shown on a single-cell scale in various tissues. Previous review articles have illustrated SPINK1′s biological functions [7,8,15][7][8][15].

2. SPINK1 Mutations and Cancer

Understanding the mutational signature of

SPINK1will improve the development and management of the step-up approach for cancer patients, specifically those harboring aberrant

SPINK1. Recently, a novel technique, the immunocapture-liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (IC-LC-MS) assay, was validated as able to detect and quantify serum SPINK1, including mutant forms N34S (SPINK1) and P55S (SPINK1) [16]. SPINK1 protects against the premature activation of trypsinogen and progression of acute pancreatitis, which may lead to carcinogenesis [17,18]. Previous studies have claimed a correlation of. Recently, a novel technique, the immunocapture-liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (IC-LC-MS) assay, was validated as able to detect and quantify serum SPINK1, including mutant forms N34S (SPINK1) and P55S (SPINK1) [16]. SPINK1 protects against the premature activation of trypsinogen and progression of acute pancreatitis, which may lead to carcinogenesis [17][18]. Previous studies have claimed a correlation of

SPINK1mutations with a higher risk for pancreatic cancer, particularly in patients with chronic pancreatitis [19]. Patients with chronic pancreatitis (CP) due to the

SPINK1gene mutation c.101A>G (

p. N34S) detected by pyrosequencing were reported to have a 12-fold higher risk of developing pancreatic cancer than controls (Cox HR: 12.0 (3.0–47.8);

p < 0.001) [20,21]. However, another cohort from Finland enrolling 188 patients with pancreatic malignant tumors showed that the N34S mutation was present in only seven cases (3.7%). The frequency of the N34S mutation in healthy controls was significantly higher than that reported in other countries [22]. A study using two pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines, PaCa44 and PancTu-I, harboring the heterozygous N34S variant further showed reduced SPINK1 levels compared with wild-type SPINK1. The negative regulation was due to the c.−4141G>T variant consistently found in the cells [23]. In addition to the frequently reported N34S mutation in the West, a retrospective study in China indicated that the c.194+2T>C mutation of< 0.001) [20][21]. However, another cohort from Finland enrolling 188 patients with pancreatic malignant tumors showed that the N34S mutation was present in only seven cases (3.7%). The frequency of the N34S mutation in healthy controls was significantly higher than that reported in other countries [22]. A study using two pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines, PaCa44 and PancTu-I, harboring the heterozygous N34S variant further showed reduced SPINK1 levels compared with wild-type SPINK1. The negative regulation was due to the c.−4141G>T variant consistently found in the cells [23]. In addition to the frequently reported N34S mutation in the West, a retrospective study in China indicated that the c.194+2T>C mutation of

SPINK1was present in 44.9% of patients with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis [24]. In particular, the metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients with chronic pancreatitis were found to harbor the c.194+2T>C mutation [25]. The aforementioned studies showed the potential association of

SPINK1mutations with the risk of cancer. However, whether those mutant forms of

SPINK1are independent factors of cancer remains to be explored.

3. SPINK1 Expression in Cancers

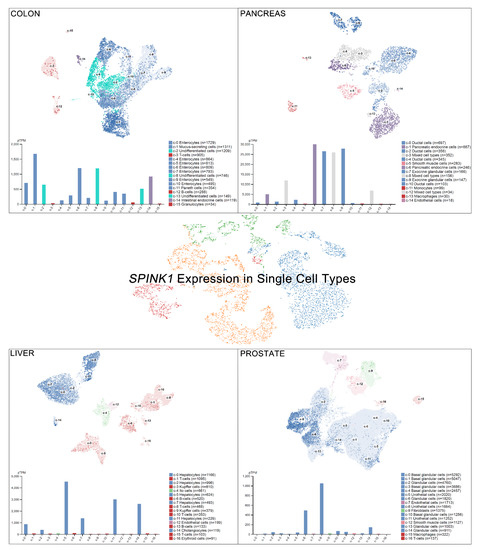

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has become a powerful tool to delineate the composition of different cell types or states in a given tissue, determined by differentially expressed gene sets [26,27,28,29][26][27][28][29]. Recently, scRNA-seq of normal tissue led to the discovery of multiple cell types contributing to cancer [30]. A new single-cell-type atlas with publicly available genome-wide expression scRNA-seq data of 192 individual cell-type clusters from 13 different human tissues was launched in November 2020 (The Human Protein Atlas, accessed on January 2021) [31]. The relative SPINK1 expression in the top four tissues displaying high SPINK1 levels, including the colon, prostate, liver, and pancreas, is shown on a single-cell scale (Figure 2). Relatively high SPINK1 expression was detected in enterocytes, mucus-secreting cells, intestinal endocrine cells, and undifferentiated cells of colon tissue. Pancreatic endocrine cells, exocrine glandular cells, and mixed cell types in the pancreas all showed SPINK1 expression. In addition, SPINK1 was specifically detected in hepatocytes and cholangiocytes compared with other cell types in liver tissue. In the prostate, SPINK1 was found in glandular cells and urothelial cells. The observation further suggests the potential sites of SPINK1 for playing roles in tumorigenesis. Importantly, data of immunohistochemical investigations were released (The Human Protein Atlas, https://www.proteinatlas.org/, accessed on January 2021) [31]. SPINK1 was relatively highly detected in tissues, including the stomach, duodenum, small intestine, colon, rectum, pancreas, and urinary bladder that is consistent with results found in colon and pancreas after comparing with single-cell RNA sequencing data. Actually, in colorectal cancer, a high percentage of positive immunohistochemical staining of SPINK1 was observed in cancer patients [32[32][33],33], suggesting a potential cause of tumorigenesis by abnormal SPINK1 overexpression.

SPINK1 expression in single-cell types. The SPINK1 expression level was analyzed by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) using different human tissues (The Human Protein Atlas_

, accessed on January 2021). RNA expression in the single-cell-type clusters identified in each tissue was visualized by a UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) plot (top) and a bar chart (bottom). The read counts were normalized to transcripts per million protein-coding genes (pTPM) for each of the single-cell clusters.

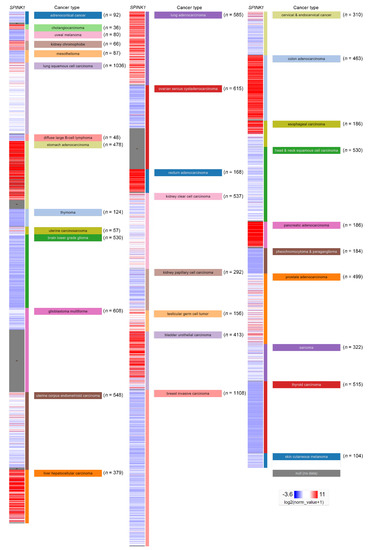

In addition, the regulatory mechanism of SPINK1 expression in cancer types has been reported. The SPINK1 gene contains an IL-6 responsive element. A connection was observed in the colorectal cancer cell lines Colo205 and HT-29, in which the SPINK1 level was increased by both fibroblast-derived and recombinant IL-6 treatment [34]. Furthermore, IL-6 autocrine signaling was reported in an ovarian clear cell carcinoma study that IL-6 could regulate SPINK1 expression [35]. Clinically, another study using immunohistochemical staining detected the SPINK1 level in a high percentage of colorectal cancer patients [33]. In a prostate cancer model, miR-338-5p/miR-421 was epigenetically silenced in SPINK1-positive prostate cancer, and miR-338-5p/miR-421 was characterized as post-transcriptionally regulating SPINK1 via 3′UTR binding [36]. The androgen receptor and corepressor REST have also been characterized as transcriptional repressors of SPINK1, while antagonists of the androgen receptors that alleviate this repression have been discovered [37]. Interestingly, SPINK1 modulates the tumor microenvironment, and its expression was specifically detected in the stromal cells of prostate cancer patients after chemotherapy [9]. In localized prostate cancer, SPINK1 was found exclusively absent in patients with homozygous PTEN deletion or ERG expressions [38,39][38][39]. In addition, the mutual exclusivity of SPINK1 expression and ETS fusion status had been reported in prostate cancer [40]. In liver cancer, a low SPINK1 expression score was found in cirrhosis patients compared with that in well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (WD-HCC) patients. In addition, a significant difference in SPINK1 expression between WD-HCC and high-grade dysplastic nodules (HGDNs) was observed, suggesting a diagnostic role for SPINK1 in hepatocellular carcinoma [41]. The SPINK1 expression level in another hepatocellular carcinoma cohort was investigated using a tissue assay of 273 paired tumor and paratumor tissues. The SPINK1 level was significantly higher in the tumor tissues (p < 0.001) and correlated with portal vein tumor thrombus formation (p < 0.019) [42]. SPINK1 may also play a pivotal role in early hepatocellular carcinoma development because the investigation showed significant demethylation of SPINK1 in early hepatocellular carcinoma compared with HGDNs. The study further indicated that SPINK1 expression may be due to ER stress-induced SPINK1 demethylation during liver cancer progression [43]. Furthermore, SPINK1 was overexpressed in up to 70% of human hepatocellular carcinomas, and its expression level exhibited a positive correlation with CDH17 [44]. SPINK1 was highly expressed in non-small cell lung cancer compared with adjacent normal tissue samples [45]. A similar result was verified in a cell line panel study showing relatively high SPINK1 protein and RNA expression levels in the H460, H1299 and A549 lung cancer cell lines compared with those in normal human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells [45]. A comprehensive project investigating the combination of multicancer transcriptomic data with matched clinical information was released by the University of California, Santa Cruz (n = 12,839) [46]. These transcriptomic data were mainly obtained after performing microarray experiments and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) on a pan-cancer scale, and the raw data were retrieved from the public database The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), showing relative SPINK1 expression after normalization in various types of cancer (Figure 3). SPINK1 was relatively highly expressed in cholangiocarcinoma, kidney chromophobe cancer, stomach adenocarcinoma and liver hepatocellular carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, rectum adenocarcinoma, testicular germ cell tumor, urothelial bladder carcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Additionally, lower SPINK1 levels were observed in uveal melanoma, mesothelioma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, thymoma, brain lower grade glioma, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma, kidney papillary cell carcinoma, breast invasive carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma, thyroid carcinoma and skin cutaneous melanoma.

Figure 3. SPINK1 expression view in a pan-cancer panel. In a pan-cancer dataset, SPINK1 expression levels were presented separately for 32 cancer types. The red color in the heat map represents high SPINK1 expression. The blue color in the heat map represents low SPINK1 expression. The raw data were retrieved from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database.

References

- Kazal, L.A.; Spicer, D.S.; Brahinsky, R.A. Isolation of a crystalline trypsin inhibitor-anticoagulant protein from pancreas. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 3034–3040.

- Stenman, U.H.; Huhtala, M.L.; Koistinen, R.; Seppala, M. Immunochemical demonstration of an ovarian cancer-associated urinary peptide. Int. J. Cancer 1982, 30, 53–57.

- Huhtala, M.L.; Pesonen, K.; Kalkkinen, N.; Stenman, U.H. Purification and characterization of a tumor-associated trypsin inhibitor from the urine of a patient with ovarian cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 13713–13716.

- Bartelt, D.C.; Shapanka, R.; Greene, L.J. The primary structure of the human pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor. Amino acid sequence of the reduced S-aminoethylated protein. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1977, 179, 189–199.

- Horii, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Tomita, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Fukushige, S.; Murotsu, T.; Ogawa, M.; Mori, T.; Matsubara, K. Primary structure of human pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (PSTI) gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987, 149, 635–641.

- Tang, X.Y.; Lin, J.H.; Zou, W.B.; Masson, E.; Boulling, A.; Deng, S.J.; Cooper, D.N.; Liao, Z.; Ferec, C.; Li, Z.S.; et al. Toward a clinical diagnostic pipeline for SPINK1 intronic variants. Hum. Genom. 2019, 13, 8.

- Mehner, C.; Radisky, E.S. Bad Tumors Made Worse: SPINK1. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 10.

- Rasanen, K.; Itkonen, O.; Koistinen, H.; Stenman, U.H. Emerging Roles of SPINK1 in Cancer. Clin. Chem. 2016, 62, 449–457.

- Chen, F.; Long, Q.; Fu, D.; Zhu, D.; Ji, Y.; Han, L.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Q.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; et al. Targeting SPINK1 in the damaged tumour microenvironment alleviates therapeutic resistance. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4315.

- Chang, C.; Zhao, W.; Luo, Y.; Xi, L.; Chen, S.; Zhao, C.; Wang, G.; Guo, J.; Xu, C. Serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal type I (SPINK1) promotes BRL-3A cell proliferation via p38, ERK, and JNK pathways. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2017, 35, 339–348.

- Chen, Y.T.; Tsao, S.C.; Yuan, S.S.; Tsai, H.P.; Chai, C.Y. Serine Protease Inhibitor Kazal Type 1 (SPINK1) Promotes Proliferation of Colorectal Cancer Through the Epidermal Growth Factor as a Prognostic Marker. Pathol. Oncol. Res. Por 2015, 21, 1201–1208.

- Mehner, C.; Oberg, A.L.; Kalli, K.R.; Nassar, A.; Hockla, A.; Pendlebury, D.; Cichon, M.A.; Goergen, K.M.; Maurer, M.J.; Goode, E.L.; et al. Serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) drives proliferation and anoikis resistance in a subset of ovarian cancers. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 35737–35754.

- Ozaki, N.; Ohmuraya, M.; Hirota, M.; Ida, S.; Wang, J.; Takamori, H.; Higashiyama, S.; Baba, H.; Yamamura, K. Serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 promotes proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells through the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol. Cancer Res. 2009, 7, 1572–1581.

- Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Su, B.; Lu, N.; Song, J.; Yang, X.; Fu, W.; Tan, W.; Han, B. Serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition through EGFR signaling pathway in prostate cancer. Prostate 2014, 74, 689–701.

- Ohmuraya, M.; Sugano, A.; Hirota, M.; Takaoka, Y.; Yamamura, K. Role of Intrapancreatic SPINK1/Spink3 Expression in the Development of Pancreatitis. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 126.

- Ravela, S.; Valmu, L.; Domanskyy, M.; Koistinen, H.; Kylanpaa, L.; Lindstrom, O.; Stenman, J.; Hamalainen, E.; Stenman, U.H.; Itkonen, O. An immunocapture-LC-MS-based assay for serum SPINK1 allows simultaneous quantification and detection of SPINK1 variants. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 1679–1688.

- Joergensen, M.T.; Brusgaard, K.; Novovic, S.; Andersen, A.M.; Hansen, M.B.; Gerdes, A.M.; de Muckadell, O.B. Is the SPINK1 variant p.N34S overrepresented in patients with acute pancreatitis? Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 24, 309–315.

- Greenhalf, W.; Levy, P.; Gress, T.; Rebours, V.; Brand, R.E.; Pandol, S.; Chari, S.; Jorgensen, M.T.; Mayerle, J.; Lerch, M.M.; et al. International consensus guidelines on surveillance for pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis. Recommendations from the working group for the international consensus guidelines for chronic pancreatitis in collaboration with the International Association of Pancreatology, the American Pancreatic Association, the Japan Pancreas Society, and European Pancreatic Club. Pancreatology 2020, 20, 910–918.

- Masamune, A.; Mizutamari, H.; Kume, K.; Asakura, T.; Satoh, K.; Shimosegawa, T. Hereditary pancreatitis as the premalignant disease: A Japanese case of pancreatic cancer involving the SPINK1 gene mutation N34S. Pancreas 2004, 28, 305–310.

- Muller, N.; Sarantitis, I.; Rouanet, M.; de Mestier, L.; Halloran, C.; Greenhalf, W.; Ferec, C.; Masson, E.; Ruszniewski, P.; Levy, P.; et al. Natural history of SPINK1 germline mutation related-pancreatitis. EBioMedicine 2019, 48, 581–591.

- Suzuki, M.; Shimizu, T. Is SPINK1 gene mutation associated with development of pancreatic cancer? New insight from a large retrospective study. EBioMedicine 2019, 50, 5–6.

- Lempinen, M.; Paju, A.; Kemppainen, E.; Smura, T.; Kylanpaa, M.L.; Nevanlinna, H.; Stenman, J.; Stenman, U.H. Mutations N34S and P55S of the SPINK1 gene in patients with chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer and in healthy subjects: A report from Finland. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 40, 225–230.

- Kereszturi, E.; Sahin-Toth, M. Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines Heterozygous for the SPINK1 p.N34S Haplotype Exhibit Diminished Expression of the Variant Allele. Pancreas 2017, 46, 54–55.

- Sun, C.; Liao, Z.; Jiang, L.; Yang, F.; Xue, G.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, R.; Sun, S.; Li, Z. The contribution of the SPINK1 c.194+2T>C mutation to the clinical course of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis in Chinese patients. Dig. Liver Dis. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2013, 45, 38–42.

- Boortalary, T.; Jalaly, N.Y.; Moran, R.A.; Makary, M.A.; Walsh, C.; Lennon, A.M.; Zaheer, A.; Singh, V.K. Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma in a Patient With Chronic Calcific Pancreatitis and a Heterozygous SPINK1 c.194+2T>C Mutation. Pancreas 2018, 47, 24–25.

- Gao, R.; Kim, C.; Sei, E.; Foukakis, T.; Crosetto, N.; Chan, L.K.; Srinivasan, M.; Zhang, H.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Navin, N. Nanogrid single-nucleus RNA sequencing reveals phenotypic diversity in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 228.

- Kim, C.; Gao, R.; Sei, E.; Brandt, R.; Hartman, J.; Hatschek, T.; Crosetto, N.; Foukakis, T.; Navin, N.E. Chemoresistance Evolution in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Delineated by Single-Cell Sequencing. Cell 2018, 173, 879–893.e13.

- Azizi, E.; Carr, A.J.; Plitas, G.; Cornish, A.E.; Konopacki, C.; Prabhakaran, S.; Nainys, J.; Wu, K.; Kiseliovas, V.; Setty, M.; et al. Single-Cell Map of Diverse Immune Phenotypes in the Breast Tumor Microenvironment. Cell 2018, 174, 1293–1308.

- Chung, W.; Eum, H.H.; Lee, H.O.; Lee, K.M.; Lee, H.B.; Kim, K.T.; Ryu, H.S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.E.; Park, Y.H.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq enables comprehensive tumour and immune cell profiling in primary breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15081.

- Peng, S.; Hebert, L.L.; Eschbacher, J.M.; Kim, S. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of a Postmenopausal Normal Breast Tissue Identifies Multiple Cell Types That Contribute to Breast Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 3639.

- Uhlen, M.; Bjorling, E.; Agaton, C.; Szigyarto, C.A.; Amini, B.; Andersen, E.; Andersson, A.C.; Angelidou, P.; Asplund, A.; Asplund, C.; et al. A human protein atlas for normal and cancer tissues based on antibody proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2005, 4, 1920–1932.

- Koskensalo, S.; Louhimo, J.; Hagstrom, J.; Lundin, M.; Stenman, U.H.; Haglund, C. Concomitant tumor expression of EGFR and TATI/SPINK1 associates with better prognosis in colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76906.

- Ida, S.; Ozaki, N.; Araki, K.; Hirashima, K.; Zaitsu, Y.; Taki, K.; Sakamoto, Y.; Miyamoto, Y.; Oki, E.; Morita, M.; et al. SPINK1 Status in Colorectal Cancer, Impact on Proliferation, and Role in Colitis-Associated Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015, 13, 1130–1138.

- Rasanen, K.; Lehtinen, E.; Nokelainen, K.; Kuopio, T.; Hautala, L.; Itkonen, O.; Stenman, U.H.; Koistinen, H. Interleukin-6 increases expression of serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 through STAT3 in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Mol. Carcinog. 2016, 55, 2010–2023.

- Mehner, C.; Miller, E.; Hockla, A.; Coban, M.; Weroha, S.J.; Radisky, D.C.; Radisky, E.S. Targeting an autocrine IL-6-SPINK1 signaling axis to suppress metastatic spread in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Oncogene 2020, 39, 6606–6618.

- Bhatia, V.; Yadav, A.; Tiwari, R.; Nigam, S.; Goel, S.; Carskadon, S.; Gupta, N.; Goel, A.; Palanisamy, N.; Ateeq, B. Epigenetic Silencing of miRNA-338-5p and miRNA-421 Drives SPINK1-Positive Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2755–2768.

- Tiwari, R.; Manzar, N.; Bhatia, V.; Yadav, A.; Nengroo, M.A.; Datta, D.; Carskadon, S.; Gupta, N.; Sigouros, M.; Khani, F.; et al. Androgen deprivation upregulates SPINK1 expression and potentiates cellular plasticity in prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 384.

- Huang, K.C.; Evans, A.; Donnelly, B.; Bismar, T.A. SPINK1 Overexpression in Localized Prostate Cancer: A Rare Event Inversely Associated with ERG Expression and Exclusive of Homozygous PTEN Deletion. Pathol. Oncol. Res. Por 2017, 23, 399–407.

- Fontugne, J.; Davis, K.; Palanisamy, N.; Udager, A.; Mehra, R.; McDaniel, A.S.; Siddiqui, J.; Rubin, M.A.; Mosquera, J.M.; Tomlins, S.A. Clonal evaluation of prostate cancer foci in biopsies with discontinuous tumor involvement by dual ERG/SPINK1 immunohistochemistry. Mod. Pathol. Off. J. United States Can. Acad. Pathol. 2016, 29, 157–165.

- Tomlins, S.A.; Rhodes, D.R.; Yu, J.; Varambally, S.; Mehra, R.; Perner, S.; Demichelis, F.; Helgeson, B.E.; Laxman, B.; Morris, D.S.; et al. The role of SPINK1 in ETS rearrangement-negative prostate cancers. Cancer Cell 2008, 13, 519–528.

- Holah, N.S.; El-Azab, D.S.; Aiad, H.A.E.; Sweed, D.M.M. The Diagnostic Role of SPINK1 in Differentiating Hepatocellular Carcinoma From Nonmalignant Lesions. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. Aimm 2017, 25, 703–711.

- Huang, K.; Xie, W.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Wei, X.; Chen, B.; Hua, Y.; Li, S.; Peng, B.; Shen, S. High SPINK1 Expression Predicts Poor Prognosis and Promotes Cell Proliferation and Metastasis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Investig. Surg. Off. J. Acad. Surg. Res. 2020, 1–10.

- Jee, B.A.; Choi, J.H.; Rhee, H.; Yoon, S.; Kwon, S.M.; Nahm, J.H.; Yoo, J.E.; Jeon, Y.; Choi, G.H.; Woo, H.G.; et al. Dynamics of Genomic, Epigenomic, and Transcriptomic Aberrations during Stepwise Hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 5500–5512.

- Shek, F.H.; Luo, R.; Lam, B.Y.H.; Sung, W.K.; Lam, T.W.; Luk, J.M.; Leung, M.S.; Chan, K.T.; Wang, H.K.; Chan, C.M.; et al. Serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) as novel downstream effector of the cadherin-17/beta-catenin axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. Oncol. 2017, 40, 443–456.

- Guo, M.; Zhou, X.; Han, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L. SPINK1 is a prognosis predicting factor of non-small cell lung cancer and regulates redox homeostasis. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 6899–6908.

- Zhu, J.; Sanborn, J.Z.; Benz, S.; Szeto, C.; Hsu, F.; Kuhn, R.M.; Karolchik, D.; Archie, J.; Lenburg, M.E.; Esserman, L.J.; et al. The UCSC Cancer Genomics Browser. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 239–240.