Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) still represents a human tumor entity with very limited therapeutic options, especially for advanced stages. Here, immune checkpoint modulating drugs alone or in combination with local ablative techniques could open a new and attractive therapeutic “door” to improve outcome and response rate for patients with HCC.

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- immunotherapy

- immune checkpoint inhibitors

- locoregional treatment

1. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

Liver cancer represents a considerable health issue due to an increasing incidence in most regions worldwide. It accounts for about 840,000 new cases and 780,000 estimated deaths–ranking 6th by incidence and 4th by cancer-related mortality for both sexes [1][2][3]. A clear male preponderance (2–3 times higher, up to five times in some countries [3][4]) is reflected by the age-standardized worldwide incidence rate of 13.9 and 4.9 per 100,000 male and female inhabitants, respectively [2]. Both, incidence and mortality rates vary by region mapping to the geographical distribution of viral hepatitis B/C (HBV/HCV) which are the most important causes of chronic liver disease and HCC [3][5]: while the highest numbers are found in eastern Asia with incidence/mortality rates of 17.7/16.0, respectively, Europe records about 4.0–6.8 new cases and 3.8–5.3 deaths from liver cancer and North America has about 6.6 new cases and 4.8 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, for example [2]. These epidemiologic figures describe the situation for primary liver cancer which mainly compromises cases with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, 75–85%), besides 10–15% cases of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma as well as other rare tumors [1].

1

1

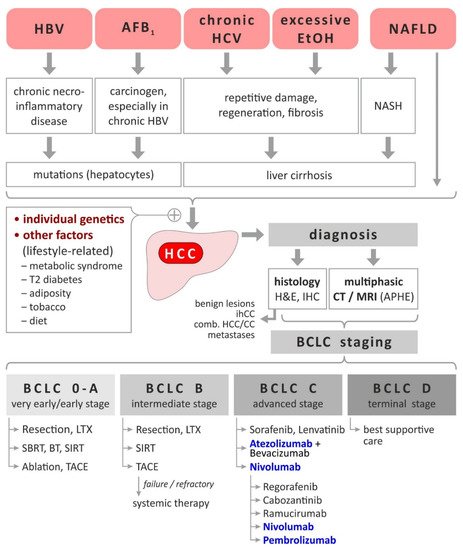

Figure 1. HCC-Etiology, risk factors, diagnosis and staging-dependent current treatment. Based on [3][5][8][9]. Immunomodulatory treatments are highlighted bold and blue. Abbreviations: AFB

1

1

2. Immunological Based Therapies in HCC

2.1. Established/Approved Immunotherapeutics in HCC

2.1.1. Established/Approved Immunotherapeutics in HCC

Treatment options in advanced HCC (BCLC C) have evolved rapidly over the last 3 years. After the implementation of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sorafenib in 2005 for advanced HCC [10], it took more than 10 years until levantinib was able to show comparable efficacy and was approved for the treatment of HCC [11]. The established first-line treatment options opened the possibility for second-line studies. After having progressed during sorafenib, treatment with regorafenib and cabozantinib showed efficacy in phase-III studies [12][13] and extended the use of TKI in HCC. Further treatment options in second-line consist of the use of ramucirumab (IgG1 targeting the extracellular domain of VEGF receptor 2), the first monoclonal antibody that has been approved for the use in HCC treatment [14]. The effect of ramucirumab was limited to those patients with elevated AFP levels. With an AFP level of higher than 400 ng/mL, the first predictive biomarker was introduced to the treatment of HCC. All those treatment options were in the pre-immune checkpoint era and consisted of TKIs or monoclonal antibodies.

Early phase II studies investigating single agent use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors showed encouraging results and let to the premature approval of pembrolizumab (target: PD-1). The results of the respective phase III studies (KEYNOTE-240 and CheckMate 459) were disappointing. KEYNOTE-240 evaluated the efficacy of pembrolizumab in second line compared to placebo. The primary endpoints, OS and PFS, were improved by the use of pembrolizumab but did not meet their pre-specified statistical significance [15]. The use of nivolumab (target: PD-1) compared to sorafenib in the first-line setting was investigated in the CheckMate-459 study. The primary endpoint OS was not significantly improved [16] but both studies showed a favorable safety profile proofing the feasibility and low toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced HCC (aHCC).

The combination of immunecheckpoint inhibitors with anti-angiogenic substances or TKI’s revealed surprisingly positive results. Within the ImBrave-150 study, atezolizumab (target: PD-L1) was combined with bevacizumab (target: VEGF) and compared against sorafenib in first-line treatment of aHCC [17]. With Hazard ratios of 0.59 and 0.58 respectively, both, PFS and OS were statistically and clinically significantly improved. The use of atezolizumab and bevacizumab has set the new standard for first-line treatment of aHCC and recent data confirmed these preliminary data with a mPFS of 6.8 months and and ORR of 27% vs. 4.3 months and 12%, respectively, for sorafenib [18].

Table 1.

| Substance | Year of Approval |

Study | Comments and Primary Endpoint |

|---|

| First-Line Options | |||

| Sorafenib | 2005 | SHARP | OS vs. placebo: 10.7 mo vs. 7.9 mo; (HR 0.69) |

| Levantinib | 2018 | REFLECT | Non inferiority to sorafenib OS: 13.6 mo vs. 12.3 mo (HR 0.92) |

| Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | 2020 | ImBrave-150 | OS vs. sorafenib OS: not reached vs. 13.2 mo (HR 0.58) |

| Second-Line Options | |||

| Regorafenib | 2017 | RESORCE | After sorafenib first-line vs. BSC OS: 10.6 mo vs. 7.8 mo (HR 0.63) |

| Cabozantinib | 2019 | CELESTIAL | After sorafenib first-line vs. BSC OS: 10.2 mo vs. 8.0 mo (HR 0.76) |

| Ramucirumab | 2019 | REACH-2 | After sorafenib first-line vs. BSC in patients with AFP >400 ng/mL OS: 8.5 mo vs. 7.3 mo (HR 0.71) |

AFP: alpha fetoprotein; aHCC: advanced hepatocellular carcinoma; BSC: best supportive care; HR: hazard ratio; OS: overall survival; mo: months.

Ongoing studies evaluate the efficacy of double immunecheckpoint inhibition using PD-L1 inhibition and CTLA4 inhibition. The NCT02519348 study has shown efficacy and tolerability for the combination of tremelimumab (target: CTLA-4) and durvalumab (target: PD-L1) [19].

2.1.2. Therapies with Immunologic Component

Locoregional therapy strategies (including transarterial embolization (TAE), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), transarterial radioembolization (TARE), and ablative therapies like radiofrequency or (RFA) and microwave ablation (MWA)) are now routinely used in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma [20]. Besides local therapeutic effects on tumor shrinkage, tumor necrosis and local reparative processes in the liver, systemic effects are already recognized, although the clinical relevance of this inflammatory response is not fully understood until now. Nevertheless, the increasing immunotherapy options for HCC raise the question, how combination treatment strategies could improve local ablative techniques and, vice versa, how those invasive procedures could impact on immunotherapy approaches. Therefore, the following chapter will summarize the known findings in animal studies and in patients as already recently reviewed in detail [21].

The first ablative experiments were performed with a locoregional VX-2 rabbit model, which served to establish the ablative techniques for clinical beginners and to investigate experimentally the “therapeutic” effects [22]. The application of VX2 was criticized due to following reasons: (i) the used VX2 tumor, an anaplastic squamous cell carcinoma induced by papilloma virus is not and does not reflect the typical HCC morphological and molecular phenotype; (ii) genetically heterogeneity between VX2 tumor specimen and animal recipient raise the question of being an allograft, rather than an autograft-model overall [21]. Therefore, animal models with spontaneous HCC development by treatment with the toxin diethylnitrosamine or by woodchuck hepatitis virus infection should reflect more the real immunological in situ situation than the “classical” VX2 tumor model [23]. A meta-analysis revealed that carcinogen induced tumor models showed the best correlation with clinical responses [24].

How does necrosis induce unspecific or even specific inflammatory response in these experimental in vitro and in vivo settings? Interestingly, while apoptosis, but not necrosis, was linked to the inflammatory reaction in vitro [25], the in vivo situation of the necrosis-inflammation-axis is quite complex, since immunogenic and non-immunogenic cell death is involved in this process [26]. Our own experiments with RFA in the VX2 model revealed that the local tumor control was paralleled by a local and systemic inflammatory reaction of activated T-cells [27]. The presented tumor antigens, released by tumor ablative techniques, could induce a localized immune response and activate a heterogeneous systematic immune response via antigen presenting cells like dendritic cells [28][29]. Additionally, combination of tumor ablation with checkpoint inhibitors like anti-CTLA4 could enhance anti-tumor immunity in vivo, too [30][31]. Consequently, the additional application of CpGs could improve this effect [32].

Figure 2. Overview of known immune effects of locoregional therapies for HCC. The arrows indicate the up- or downregulation of the observed immune effects. Based on [33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41]. Abbreviations:

90

- (1)

- (2)

-

The RFA associated T cell response is specific to thermally ablated HCC extracts [35][50] and is also specific for tumor-associated antigens [36][51]. Furthermore, patients receiving RFA showed reduced frequency of myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which inversely correlates with tumor progression or relapse [37][52]. Treatment with RFA or TACE induces glypican-3 peptide specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes compared to surgical resection which is a very interesting target for typical Glypican-3 overexpressing HCCs [38][53].

- (3)

- (4)

Finally, ongoing clinical trials investigated the combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors and locoregional ablative therapeutic strategies: Greten et al. initiated a clinical trial with 39 HCC patients who progressed after sorafinib therapy with a locoregional therapy after tremelimumab treatment [21] and confirmed the median overall survival of 10.9 months with a one complete and seven partial response as seen in an earlier study [42]. The additional molecular analysis of the peripheral blood of these treated patients revealed an increase of the PD1 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells.

https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/

Table 2.

| Start Date | NCT | Title | Local Interventions | Immuno- Modulator |

Phase |

|---|

| 01/2020 | NCT04220944 | Combined locoregional treatment with immunotherapy for unresectable HCC. | MWA/TACE | Sintilimab | 1 |

| 05/2019 | NCT03753659 | IMMULAB-immunotherapy with pembrolizumab in combination with local ablation in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | RFA, MWA, Brachytherapy, TACE | Pembrolizumab | 2 |

| 11/2019 | NCT04273100 | PD-1 monoclonal antibody, lenvatinib and TACE in the treatment of HCC | TACE | PD-1 mAb and lenvatinib | 2 |

| 09/2020 | NCT04518852 | TACE, Sorafenib and PD-1 monoclonal antibody in the treatment of HCC | TACE | sorafenib and PD-1 mAb | 2 |

| 05/2019 | NCT03867084 | dafety and efficacy of pembrolizumab (MK-3475) versus placebo as adjuvant therapy in participants with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and complete radiological response after surgical resection or local ablation (MK-3475-937/KEYNOTE-937) | Local ablation | Pembrolizumab | 3 |

| 05/2019 | NCT04268888 | Nivolumab in combination with TACE/TAE for patients with intermediate stage HCC | TACE/TAE | Nivolumab | 2/3 |

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; MWA: microwave ablation; RFA: radiofrequency ablation; TACE: trans-arterial chemo-embolization; TAE: trans-arterial embolization.

Under these circumstances, the clinical efficacy of immune modulation via checkpoint inhibitors is essentially influenced by the baseline immune response and by triggering pre-existing immunity, leading to the concept of “hot” and “cold” tumors on the basis of level and spatial distribution of CD3+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration into the tumor [43][44]. The already mentioned response rate of e.g., atezolizumab and bevacizumab in HCC is mostly comparable to a rate of “hot” HCC of about 20–30% [45][46]. Although this is in line with results found in many other cancers, it is surprising for HCC since the liver plays a central role in human immune regulation via the complex interaction of sinusoidal endothelial cells and resident macrophages (Kupffer cells) with NK cells and different CD4+/CD8+ T cell subsets and many HCCs develop on the basis of an underlying chronic inflammatory process [47][48]. As recently discussed elsewhere, the main issue to overcome the limitations of immunotherapy (alone or in combination) is to include the specific immunogenicity of tumor cells in relation to immune escape mechanisms in HCC [45]. Possible new treatment strategies for “cold” HCC could be based on intensive immune priming (e.g., vaccines, adoptive cell therapy or oncolytic approaches) and modulation (e.g., classical radiotherapy, chemotherapy and targeted therapy) to essentially enhance response to checkpoint inhibitors [43] as also addressed in the following sections.

2.2. Future Options of HCC Linked Immunmodulation

2.2.1. TIM-3

T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (TIM-3), alias hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2 (HAVCR2)) is an immunosuppressive surface molecule that is expressed on T cells, dendritic cells, NK cells, macrophages and also on HCC cells [49]. It is commonly co-expressed with other immune checkpoint receptors like PD-1. Activation of TIM3 leads to immune exhaustion of CD8

+

+

reg) is associated with advanced tumor stage [50]. On macrophages, TIM-3 can stimulate the M2 polarization and promote tumor growth by increasing IL-6 secretion [51]. Not surprisingly, TIM-3 expression has thus been correlated to poor prognosis in various human cancers, including HCC [52][53][54]. Four ligands binding to TIM-3 have so far been identified: Galectin-9, phosphatidylserine, high-mobility group protein B1 (HGMB1) and carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule-1 (CEACAM-1) [55]. Galectin-9 is produced by numerous cells types, including B and T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells but also by epithelial cells, cancer cells and fibroblasts. In HCC, opposing effects of Galectin-9 have been described that are not well understood so far: while it is able to induce apoptosis in in vitro and in in vivo HCC models [56], it contributes to the immune exhaustion in HBV-associated HCC in patients and is a predictor for poor prognosis [54]. Interestingly, high levels of Galectin-9 have also been linked to advanced stages of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients, underlining the connection between chronic inflammatory liver damage, fibrosis and HCC [57].

Table 3) [50][55]. While several compounds investigate TIM-3 blockade in various solid tumors, only one investigator sponsored study is specifically looking into HCC. Here, the anti-TIM-3 IgG4 antibody cobolimab is used in combination with the anti-PD1 antibody dostarlimab (both manufactured by Tesaro/GSK) in adult patients with BCLC stage B or C HCC and no prior systemic therapy. The study is ongoing and no interim data have been reported so far.

Table 3.

| Compound | Company | Status/Comment |

|---|

| BMS-986258 | BMS | Phase 1 in solid tumors in combination with nivolumab |

| Cobolimab (TSR-022, GSK4069889) | Tesaro/GSK | Various Phase 1 studies ongoing +PD-1 in HCC (NCT03680508) |

| INCAGN02390 | Incyte | Phase 1 in solid tumors |

| LY3321367 | Eli Lilly | PD-1/TIM-3 bispecific Development stopped |

| RG7769 (RO7121661) | Roche | PD-1/TIM-3 bispecific Phase 1 in solid tumors |

| Sabatolimab (MBG 453) | Novartis | Only in hematologic malignancies |

| Sym023 | Symphogen | Phase 1 in combination with PD-1 and/or LAG-3 antibodies |

2.2.2. LAG-3

+

+

reg, NKT cells. B cells, NK cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and on tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) [58]. It regulates the immune response by inhibiting the proliferation and activation of T cells, by inducing T

reg and by blocking T cell activation from antigen presenting cells (APCs) [59]. LAG-3 is commonly co-expressed with PD-1 in T cell exhausted cancers and contributes to resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy [60][61][62]. For LAG-3, too, four ligands have been identified today: major histocompatibility complex class II proteins (MHC-II) [63], liver sinusoidal endothelial cell lectin (LSECtin) [64], Galectin-3 [65] and fibrinogen-like protein 1 (FGL-1) [66]. All ligands are of relevance for HCC formation: while MHC-II is expressed on activated APCs (Kupffer cells), the other ligands can be expressed by hepatocytes or sinusoidal endothelial cells which also play a role in chronic liver damage, fibrotic remodeling, angiogenesis and tumor formation [67][68][69][70][71]. LAG-3 expression has therefore also been associated to poor prognosis in various human cancers including HCC [72][73].

Preclinical data indicated a strong anti-tumor efficacy of LAG-3 antagonists, esp. when combined with anti-PD-1 agents [74][75][76][77]. Thus, about 15 large-molecule antagonists against LAG-3 (either mono- or bispecific against PD-1) are currently investigated preclinically or in early clinical studies (recently reviewed by Lecocq et al. [58]). Yet, single agent activity if those compounds was only limited and most trials now combine anti-LAG-3 with anti-PD-1 approaches. Currently, five studies investigating such approaches in HCC are listed at

Table 4.

| Compound | Company | Combination | N | Phase | NCT |

|---|

| INCAGN02385 | Incyte | 22 (advanced solid tumors) | 1 | NCT03538028 | |

| Relatlimab | BMS | Nivolumab | 20 | 1 | NCT04658147 |

| Relatlimab | BMS | Nivolumab | 250 | 2 | NCT04567615 |

| SRF388 | Surface Oncology | 122 (advanced solid tumors, with n = 40 HCC expansion arm) | 1 | NCT04374877 | |

| XmAb®22841 | Xencor | Pembrolizumab | 242 (advanced solid tumors) | 1 | NCT03849469 |

2.2.3. TIGIT

reg and T helper cell populations under resting conditions to exert an immunosuppressive condition [78]. CD155 was identified as the main ligand, mainly expressed on DCs, macrophages, B and T cells. CD112 (Nectin-2) and CD113 (Nectin-3) bind to TIGIT with lower affinity and all three ligands can also be detected in the liver. TIGIT was found to be upregulated in patients with advanced fibrosis [79] and in chronic viral hepatitis leading to HCC [80]. In preclinical HCC models, TIGIT contributed to immunosuppressive effects and potentially resistance to PD-1 treatment [81][82]. In clinical samples, TIGIT expression increased with tumor dedifferentiation and with higher AFP expression [83].

Several monoclonal anti-TIGIT antibodies, usually IgG1 subtypes, are currently undergoing early clinical testing (recently reviewed by Harjunpaa and Guillerey [78]). Most compounds are tested in combination with anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies but no study is specifically investigating HCC yet. Recently, tiragolumab in combination with atezolizumab received FDA breakthrough therapy designation for the first-line treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with high PD-L1 expression and no mutations in EGFR or ALK [84]. Further studies that also investigate HCC are expected. For other compounds, e.g., vibostolimab (MK-7684), etigilimab (OMP-313M32), domvanalimab (AB-154), BMS-986207, ASP8374 or BGB-A1217 are currently in Phase 1 studies in various solid tumors with a focus on NSCLC.

2.2.4. B7-H6

The B7 receptor family (alias natural cytotoxicity triggering receptor 3 or NCR3, Ligand 1) represents co-receptors to e.g., CTLA-4 or PD-1 [85]. B7-H6 is a ligand to the activating receptor NKp30 on NK cells and thus contributes to their activation [86]. B7-H6 mediated activation of NK cells leads to cytokine release (IFN-g) and enhanced cytotoxicity. Besides immunological effects, B7-H6 does also regulate intracellular signaling pathways, esp. STAT3 signaling, which are associated with apoptosis inhibition and induction of cell proliferation and therefore has a dual role in cancer cell growth [87][88].

While B7-H6 is usually not expressed in normal tissues, it is commonly found in different human cancers like small cell lung cancer [89], esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [90], gliomas [91], ovarian cancer [92] or HCC [88][93], where it is associated with poorer outcome. Unfortunately, no agents modulating B7-H6 signaling on tumor or NK cells are currently available [94].

2.2.5. CD47-SIRPa

CD47 is broadly expressed on normal cells, including erythrocytes. It belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily and displays a “don’t eat me”-signal to macrophages and other phagocytes. Binding of CD47 to its receptor signal regulatory protein a (SIRPa) on macrophages inhibits phagocytosis activation and can contribute to tumor formation [95][96]. CD47 is therefore overexpressed on various hematologic and solid tumors to evade the cellular immune response, including HCC where it is also associated to poorer outcome [97]. Consequently, blocking CD47-signaling inhibited growth of HCC models and restored sensitivity to chemotherapy [98].

Activation of CD47 on tumor cells can also lead to caspase-independent cell death induction, although the exact molecular mechanisms are still not completely understood [99]. Therapeutic approaches currently focus on inhibiting the CD47-SIRPa binding to activate phagocytosis of cancer cells and several small and large molecule inhibitors are undergoing clinical investigations. Small molecule inhibitors are currently in preclinical stage only and have been recently reviewed elsewhere [100].

Table 5.

| Compound | Company | Status/Comment |

|---|---|---|

| AK117 | Akeso | Phase 1 |

| ALX148 | ALX Oncology | Phase 2 combinations |

| AO-176 | Arch Oncology | Phase 1, combination with paclitaxel |

| CC-90002 (INBRX103) |

Celgene | Phase 1 |

| HX009 | Hanxbio | Phase 1 |

| IBI188 | Innovent Biologics | Phase 1 |

| IBI322 | Innovent Biologics | Phase 1 |

| IMC-002 | ImmuneOncia Therapeutics | Phase 1 |

| Magrolimab (Hu5F9-G4) |

Gilead | Phase 3, received breakthrough therapy designation for MDS, Phase 1b combination studies in solid tumors |

| SGN-CD47M | Seattle Genetics | Terminated |

| SRF231 | Surface Oncology | Phase 1 completed |

| ZL-1201 | ZaiLab | Phase 1 |

Recently, a Phase 1 study with the bi-functional SIRPa-Fc-CD40L antibody SL-172154 was initiated (NCT04406623). This agent targets CD47 on tumors and CD40 on antigen presenting cells to enhance antigen presentation to T cells and to induce tumor cell killing.

(INBRX103)CelgenePhase 1HX009HanxbioPhase 1IBI188Innovent BiologicsPhase 1IBI322Innovent BiologicsPhase 1IMC-002ImmuneOncia TherapeuticsPhase 1Magrolimab

(Hu5F9-G4)GileadPhase 3, received breakthrough therapy designation for MDS, Phase 1b combination studies in solid tumorsSGN-CD47MSeattle GeneticsTerminatedSRF231Surface OncologyPhase 1 completedZL-1201ZaiLabPhase 1

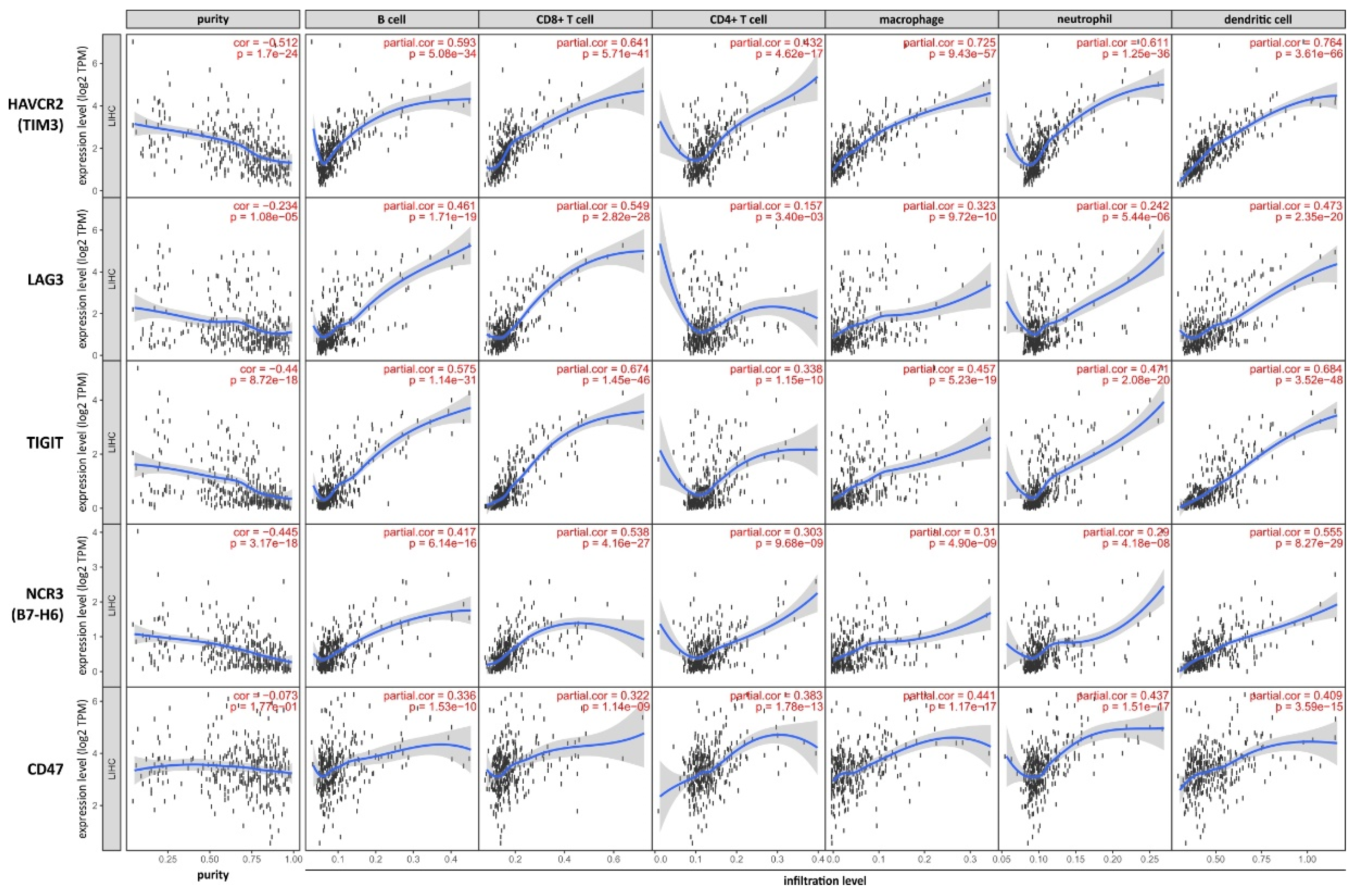

2.2.6. Additional in-Silico-Analysis of HCC Linked Immunmodulation via TUMOR Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER)

We performed an additional in silico analysis of TIM3, LAG3, TIGIT, B7-H6 and CD47-SIRPa to explore the correlation of these markers of immunomodulation in situ by using the online platform TIMER, which is based on 10,897 samples across 32 cancer types from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [101]. This included 363 primary HCC samples with mainly male patient population (66%) of caucasian ethnicity (60%) showing mostly a moderate differentiation (50%) and a relative homogenous UICC-stage distribution (Stage I 39%, II, 22%, III 31% and IV 3%. missing 6%) as already published [46].

Figure 3.