Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) may further progress to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). NASH-related HCC is currently the most rapid-growing indication for liver transplant in HCC patients.

- NAFLD

- NASH

- fibrosis

- metabolic syndrome

- obesity

- rats

- diet

1. Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a wide-spectrum disease, ranging from simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which may further progress to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1].

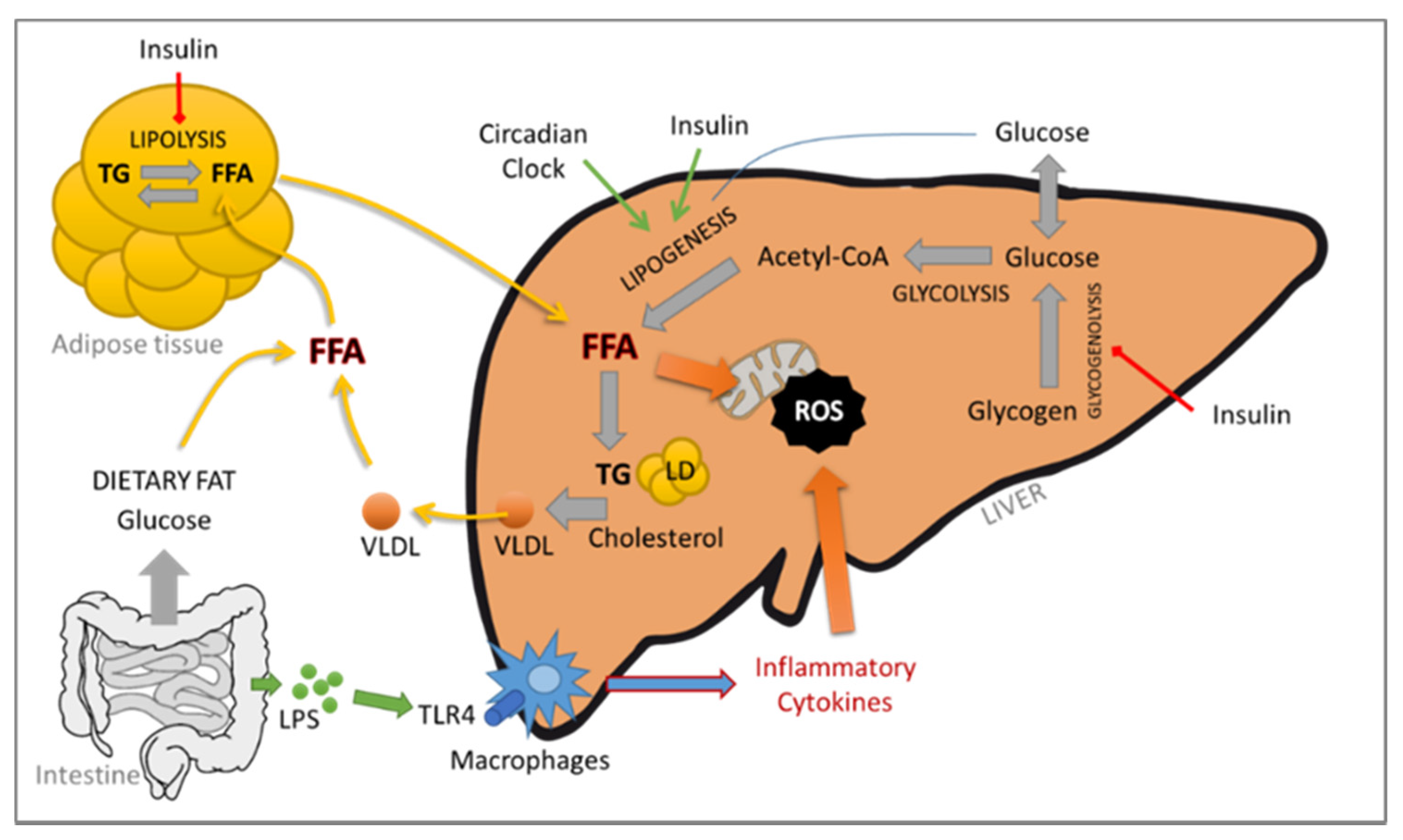

The contribution of the adipose tissue–liver axis is also critical. In fact, the adipose tissue is an active endocrine and immune organ capable of producing several mediators responsible for the crosstalk between the liver and the adipose tissue, such as leptin, IL-6 and TNF-α, which play a central role in NAFLD/NASH (see Figure 1).

NASH, obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus are nowadays recognized as risk factors for the development of HCC [2]. NASH-related HCC is currently the most rapid-growing indication for liver transplant in HCC patients [3]. HCC is the most common form of liver cancer worldwide; it holds the sixth position in terms of cancer incidence and is the third-leading cause of cancer-related deaths [4]. Although the molecular pathogenesis of the hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV and HCV, respectively) and its contribution to HCC has been widely studied, that of NASH remains a challenge. The mechanisms leading to cancer development are not fully elucidated, but interestingly, cirrhosis might not be a prerequisite (for recent reviews, see [5][6][7]), suggesting the involvement of different or additional pathways.

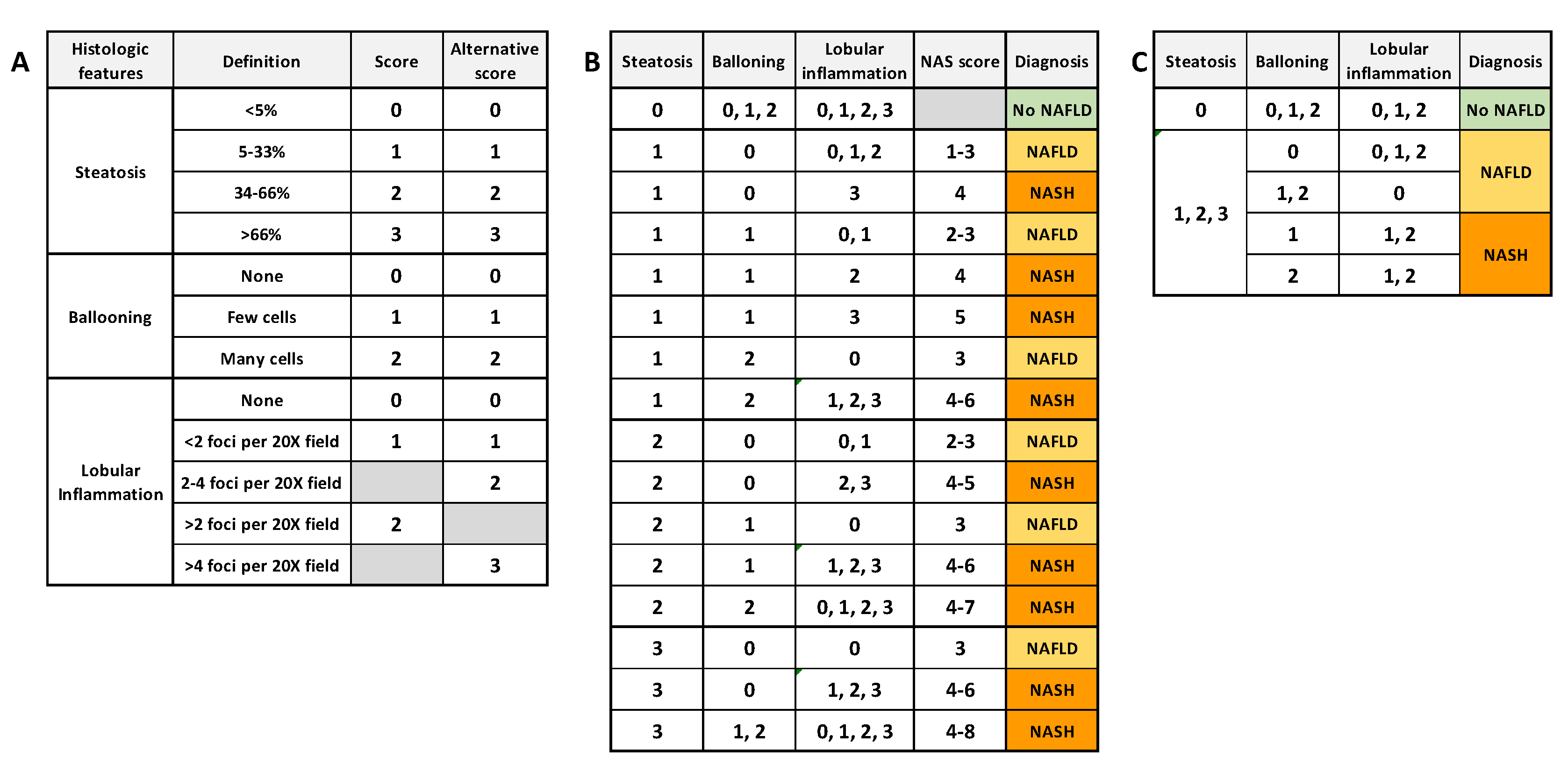

Liver biopsies remain the gold standard to distinguish NAFLD from NASH and to diagnose NASH and HCC. This is an invasive and costly procedure in which clinicians have to manage the accuracy, pain and patient safety. Nevertheless, biopsies allow characterizing and evaluating in situ the grade and stage of NASH, which is not achievable using noninvasive tests. The NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN) proposed an “NAFLD activity score” (NAS) to stage NAFLD biopsies. This score is based on the unweighted sum of the score for steatosis (0–3), hepatocellular ballooning (0–2) and lobular inflammation (0–3) [8], or (0–2) [9]. Kleiner et al. [8] proposed that a NAS score ≤ 3 is considered as “no NASH” (NAFLD if steatosis ≥ 1) and a score ≥ 4 is considered as definitely afflicted with NASH. Bedosa et al. proposed steatosis score as criteria of entry and the presence of all histologic features to diagnose NASH. FigureFigure 2 2 summarizes the algorithms commonly used for NASH and NAFLD histological determination. More recently, another NASH grading, the “steatosis–activity–fibrosis” (SAF) system was proposed. It is based on the semiquantitative scoring of steatosis (S), activity (A) and fibrosis (F), with steatosis being less weighted [9]. In this system, all features are needed to diagnose NASH, even with the lowest score. Ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes with or without fibrosis is the key feature that differentiates NASH from NAFLD.

Figure 2. Common algorithms for NAFLD and NASH scoring. (A) semiquantitative histology scoring for each histologic feature. (B) Diagnosis algorithm based on NAS score (NASH if NAS score ≥ 4) [8]. (C) Diagnosis algorithm based on unweighted histologic features (NASH if all features present, whatever the score) [9].

2. Modeling Diet-Induced NAFLD and NASH in Rats

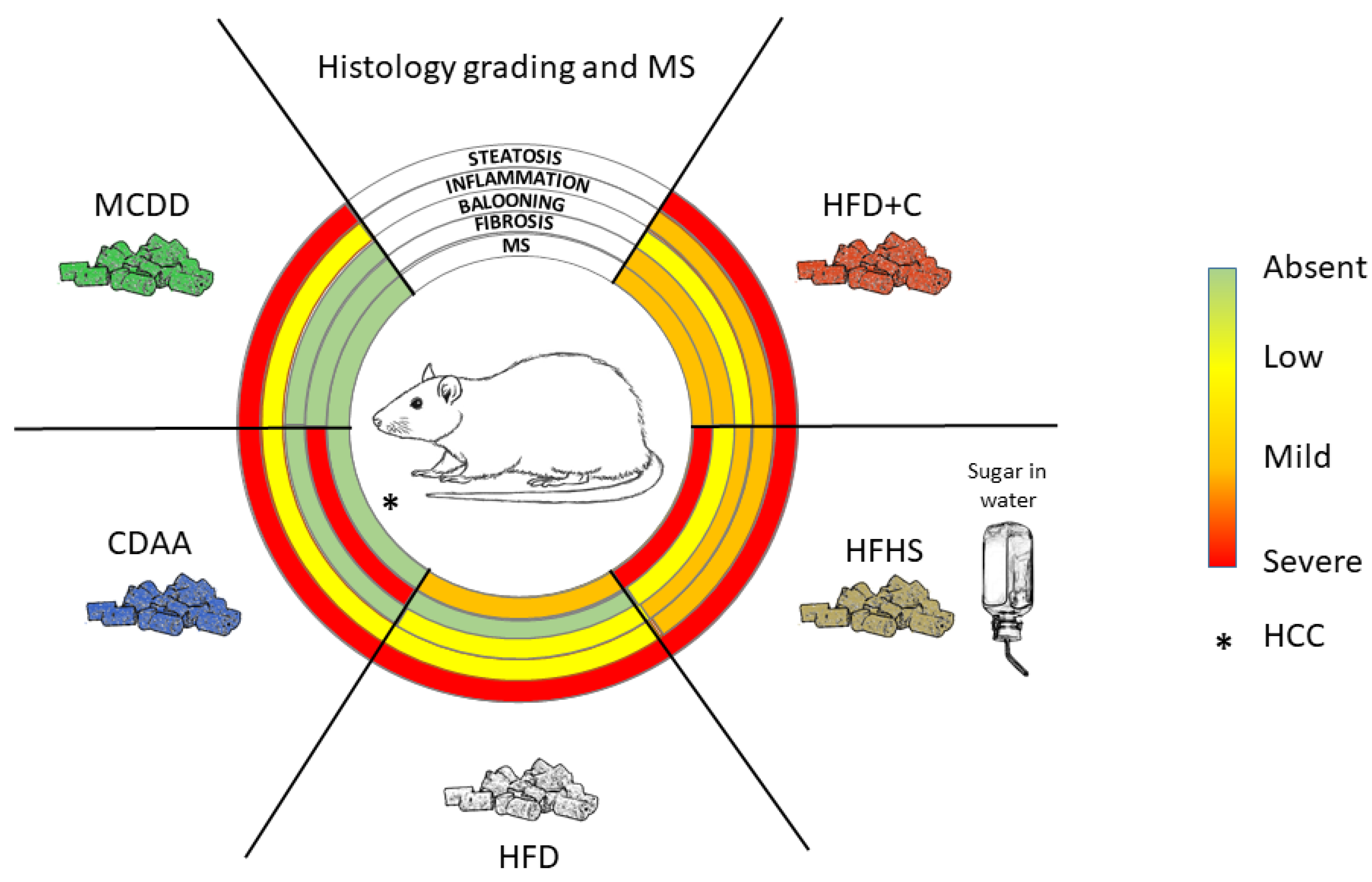

As summarized in Figure 3, a large number of diet-induced NAFLD/NASH models have been developed in rats. However, they closely mimic mouse models, and no original approaches have been proposed so far. Interestingly, with the exception of the MCDD model, dietary models were usually more efficient in triggering liver and systemic pathologies related to NAFLD and NASH in rats than in mice. However, one should keep in mind that these models are difficult to compare and replicate because of divergences in protocol length, diet ingredient origins and composition (which bear seasonal variations), genetic backgrounds of the animals, age of the animals and other uncontrolled parameters. The effects of external factors such as temperature or the circadian clock on NAFLD and NASH development in rats have been poorly described. More experiments should be performed to consolidate the influence of these factors for preclinical models based on rats. Nevertheless, the majority of these nutritional models do not completely reflect the human diet, rarely developed advanced fibrosis and did not lead to HCC, the end-point progression of NASH.

Limiting factors in developing transposable models are the time frame required in humans to establish a certain liver disease and the different metabolic rates affecting liver homeostasis. In this context, conciliating the highest relevance of diet-induced NAFLD models with the time constraints of drug testing in preclinical models might represent an unreachable goal, and the low percentage of patients that progress to NASH worsens the problem. Nevertheless, current bad dietary habits and increasing incidence of metabolic syndrome worldwide urge us to improve our in vivo approaches and continue our efforts to propose highly transposable animal models. In regard to the current published data, rat models might be helpful in such a quest.

Each model has its strengths and shortcomings. To answer a specific research question or to test a specific therapeutic compound, one should select the most appropriate model corresponding to the stage of development of the liver disease being targeted.

References

- Farrell, G.C.; Larter, C.Z. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology 2006, 43, S99–S112.

- Bhaskaran, K.; Douglas, I.; Forbes, H.; dos-Santos-Silva, I.; Leon, D.A.; Smeeth, L. Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: A population-based cohort study of 5.24 million UK adults. Lancet 2014, 384, 755–765.

- Wong, R.J.; Cheung, R.; Ahmed, A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S. Hepatology 2014, 59, 2188–2195.

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424.

- Anstee, Q.M.; Reeves, H.L.; Kotsiliti, E.; Govaere, O.; Heikenwalder, M. From NASH to HCC: Current concepts and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 411–428.

- Cholankeril, G.; Patel, R.; Khurana, S.; Satapathy, S.K. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Current knowledge and implications for management. World J. Hepatol. 2017, 9, 533–543.

- Lequoy, M.; Gigante, E.; Couty, J.P.; Desbois-Mouthon, C. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the context of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): Recent advances in the pathogenic mechanisms. Horm Mol. Biol Clin. Investig. 2020, 41.

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; Ferrell, L.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Torbenson, M.S.; Unalp-Arida, A.; et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1313–1321.

- Bedossa, P.; Poitou, C.; Veyrie, N.; Bouillot, J.L.; Basdevant, A.; Paradis, V.; Tordjman, J.; Clement, K. Histopathological algorithm and scoring system for evaluation of liver lesions in morbidly obese patients. Hepatology 2012, 56, 1751–1759.