MR spectroscopy (MRS) and spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) obtain metabolic information noninvasively from nuclei spins. For in vivo applications, common MR-active nuclei are protons (1H), phosphorus (31P), carbon (13C), sodium (23Na), and xenon (129Xe). The most common are protons due to their high gyromagnetic ratio and natural abundance in the human body. Since most metabolic processes involve carbon, 13C spectroscopy is a valuable method to measure in vivo metabolism noninvasively [1,2,3]. 13C spectra are characterized by a large spectral range (162–185 ppm), narrow line widths, and low sensitivity due to the low gyromagnetic ratio (a quarter as compared to protons) and natural abundance of 1.1% in vivo. However, the sensitivity can be increased with the use of 13C-enriched agents and by hyperpolarization.

Hyperpolarized (HP) 13C MRI is a method that magnetizes 13C probes to dramatically increase signal as compared to conventional MRI [3]. Metabolic and functional HP 13C MRI is a promising diagnostic tool for detecting disorders linked to altered metabolism such as cancer, diabetes, and heart diseases [4], increasing sensitivity sufficiently to map metabolic pathways in vivo without the use of ionizing radiation, as in positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. Metabolic imaging using HP 13C compounds has been translated successfully into single-organ examinations in healthy controls and various patient populations [5,6,7,8,9,10].

- hyperpolarized carbon-13 MRI

- review

- clinical application

1. Hyperpolarized Carbon-13 MRI

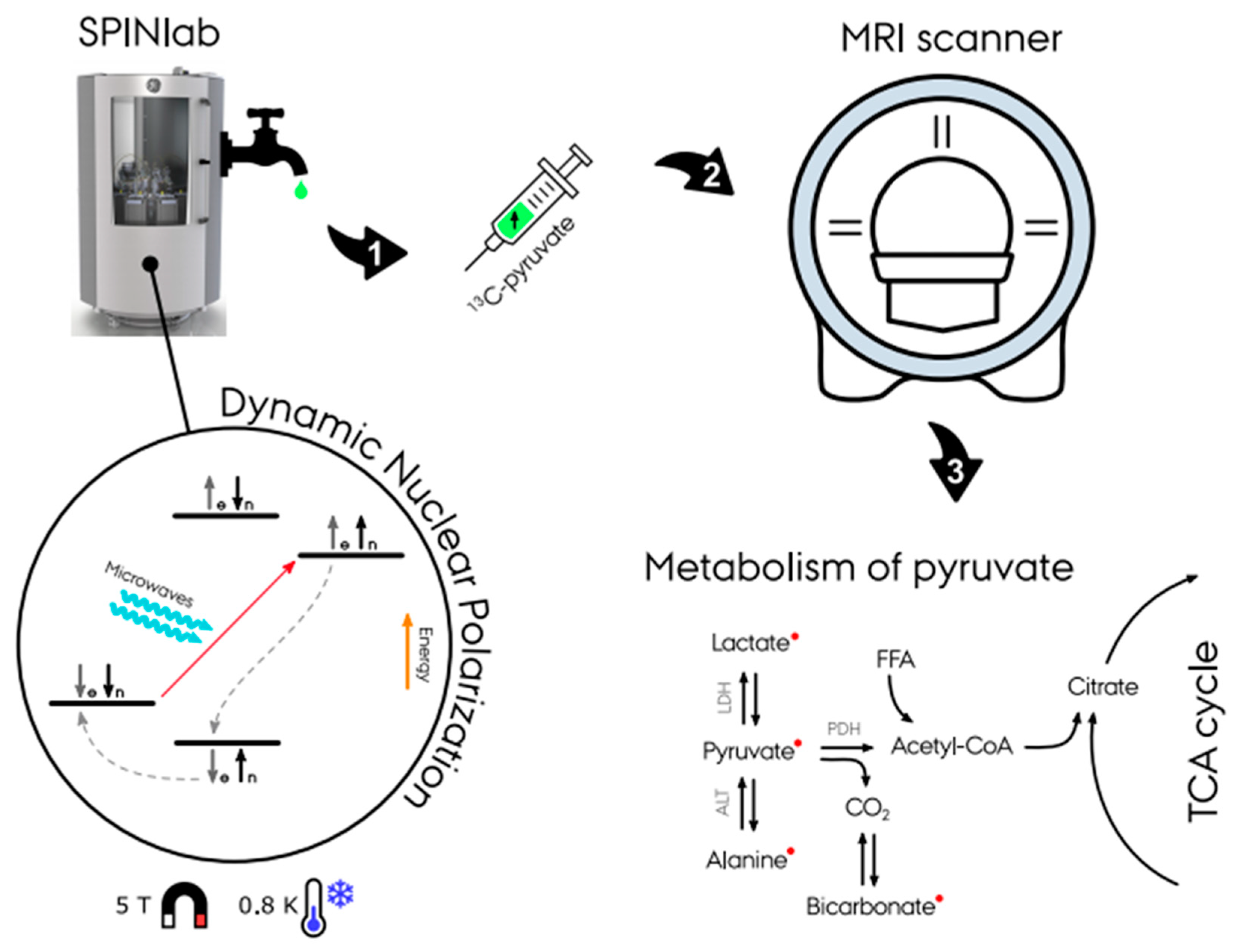

C-enriched compounds for metabolic imaging studies are most commonly hyperpolarized via dynamic nuclear polarization with subsequent dissolution (d-DNP) (

) [1]. A sample of the probe (typically (1-

C) pyruvate) and a radical with an unpaired electron is placed in a 0.8 K cold environment at 5 T within the hyperpolarizer (e.g., SPINlab (GE Research Circle Technology Inc., GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA)). These unpaired electron spins are polarized to nearly 100% at this temperature and magnetic field strength. The sample is then irradiated at the electron spin resonance frequency (e.g., 140 GHz at B0 = 5 T) to transfer the high polarization from the electron spins to the less polarized

C-enriched molecules of the sample, which typically takes 30–180 min [2][3][4]. Following this procedure, the sample is then rapidly dissolved in a hot water solution to obtain an injectable solution matching the body pH, temperature, and osmolarity before injection. After a final quality assessment, the hyperpolarized solution can be injected into the subject, preferably via an injector. Following the injection of the probe, optimized fast MR sequences for the targeted organs image the uptake and subsequent metabolic conversion of the hyperpolarized

C probe. The hyperpolarized probes are diluted heavily in the body and relax due to the spin-lattice (T1) decay. Radio-frequency (RF) excitation and metabolic conversion lead to further signal depletion. A hyperpolarized experiment is typically completely relaxed within minutes (1–2 min). Due to low concentrations, multiple hyperpolarized scans could be performed in the same scan session. Nevertheless, the polarization process requires up to 180 min, and the polarizer, e.g., the SPINlab, has a maximum capacity of four units. In combination with the cost of the hyperpolarized probes and ethical considerations, experiments are often limited to injecting a single dose.

Illustration of the hyperpolarizing experiment in a SPINlab dissolution dynamic nuclear polarizer (d-DNP). First, the dissolution of

C-pyruvate is placed in a 0.8 K cold environment at 5 T within the DPN to achieve hyperpolarization. Secondly, the dissolution achieves massively increased magnetic properties and is ready for injection into the experiment subject. With the use of fast MR sequences, spectra and images of the pyruvate metabolism is achieved (Courtesy of Christian Ø. Mariager).

The list of HP

C probes currently includes more than 24 different metabolites. A description of their chemical structures is given by Keshari et al. [5]. A description of the T1, chemical shift, applications, metabolic, and physiological processes of the most common probes has recently been published in a paper by Wang et al. and is considered outside the scope of this paper [3].

2. Applications of Hyperpolarized Carbon-13 MRI

2.1. Hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate: The Most Used Biomarker

Following injection into the bloodstream, the hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate is transported to the tissue of interest, whereafter the [1-13C]pyruvate is transported into the cells, mediated by the monocarboxyl transporters (MCTs). In the cytosol, the pyruvate is then either enzymatically converted into lactate via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) or alanine via alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or further transported into the mitochondria where it undergoes another enzymatic exchange reaction into CO

via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). The CO

is then rapidly converted into bicarbonate via carbonic anhydrase (

). The glycolytic activity in the cytosol is estimated by (1) the [1-

C]pyruvate conversion to [1-

C]lactate via the enzyme LDH and (2) mitochondrial TCA cycle activity, determined by the irreversible conversion of [1-

C]pyruvate to bicarbonate (HCO

) by the enzyme PDH [6].

2.2. Oncology

The existing publications with clinical trials of HP

C MRI are dominated by oncologic applications because this technology is particularly well suited for studying cancer. Elevated glycolysis and thus lactate production even under sufficient oxygen availability, denoted by the Warburg effect [7], is a fundamental property of many cancers [8]. This phenomenon is indicated by an upregulation of the pyruvate to lactate conversion [9]. Therefore, imaging of the metabolic conversion of [1-

C]pyruvate into [1-

C]lactate holds particular promise for cancer diagnosis as well as monitoring of response to treatment [10]. The first clinical

C study targeted prostate cancer in 2013 [11]. As of today, [1-

C]pyruvate has been applied clinically in several different cancer types ranging from prostate [11][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18], pancreas [19], breast [20][21][22], brain [23][24][25], to kidney [26]. However, several studies are on the way as indicated by assessment of studies on clinical.trails.gov (

) and EudraCT (

). Future clinical studies might include probes such as urea (perfusion) and glutamine [27].

2.3. Brain

The metabolic imaging of the brain has been applied in multiple sclerosis [28], stroke [29], traumatic brain injury [30][31][32], and brain tumors (mentioned in the Oncology section). Brain metabolism must consider the blood–brain barrier (BBB), which limits the uptake into brain tissue of hyperpolarized probes and thus ultimately the obtainable signal in the brain. This has been an obstacle for pre-clinical studies in which the animals are anesthetized [33][34][35]. Conventionally, anesthetics are not needed in brain studies in humans; nevertheless, in some cases of intensive care patients, children (2–10 years old), or claustrophobic patients it may be preferred to apply sedation prior to the examinations, though this method can complicate metabolic response. Brain studies using multichannel receiver head coils can increase cortical signal at the expense of inhomogeneous receiver profiles and less signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the center of the brain [36][37][38][39]. Clinical trials of the brain (non-cancer) are reported in three studies on healthy brain (n = 4 [40]; n = 4 [4]; n = 14 [2]).

2.4. Cardiovascular Disease

The MRI of cardiovascular diseases commonly evaluates the restriction of blood flow and ischemic areas of the heart [41]. It is, however, well established that the metabolic balance between the fat and sugar utilization of the heart is important in determining the underlying pathophysiology and best treatment for the individual patient [42]. HP

C MRI has been shown to measure the metabolism and perfusion of the heart [43], which can be advantageous for evaluation of myocardial complications associated with diabetes, ischemic heart disease, cardiac hypertrophy, and heart failure [44][45]. The ability to image in rapid succession ensures that HP

C MRI can be incorporated in stress test imaging sessions without adding significant time to these protocols. Cardiac imaging protocols need to consider cardiac cycle timing, motion correction, distortion correction, etc. [46][47]. To date, only a few clinical studies have been performed on the heart covering initially normal hearts (n = 4) [48] and later hearts of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2MD = 5, HC = 5) [49]. Evaluation of the pre-clinical literature supports a growing intention for the transition of HP

C MRI towards cardiac applications [50].

2.5. Kidney Disease

There is a lack of good biomarkers for early diagnosis, patient stratification, and treatment monitoring for kidney diseases. MRI is increasingly being used to characterize important pathophysiological processes such as perfusion, fibrosis, and oxygenation [51][52].

Hypoxia is a hallmark of kidney disease, and thus metabolic imaging techniques able to depict either pO

directly or the indirect effect of hypoxia are warranted. Hyperpolarized [1-

C]pyruvate studies have been demonstrated to allow differentiation of various renal pathophysiological conditions in pre-clinical models of diabetes, acute kidney disease (AKI), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [53][54][55][56]. The use of gadolinium-based contrast agents is contraindicated in patients with renal insufficiency [57]. Thus, alternative non gadolinium-based biomarkers to noninvasively determine hemodynamic properties, perfusion, and glomerular filtrations constitute a valuable tool for a patient group in which repeated exposure to ionizing radiation is a concern [58][59][60]. Currently, only one non-cancer human kidney study is underway.

From the pre-clinical indications, it is very likely that metabolic and functional imaging with HP

C MRI will be a future diagnostic tool in kidney disease. The results are promising in the application of [1-

C]pyruvate and have shown potential with other carbon-based probes [1,4-

C]fumarate,

C-urea [61] and [1-

C]lactate [62]. Alternative biomarkers with improved relaxation properties also hold great promise in perfusion assessment [63].

2.6. Liver Disease

Currently, most of the literature regarding liver disease is related to liver cancer. However, there is an increasing interest in the application of HP

C MRI in diagnosis and monitoring of compilations related to liver disease in pre-clinical studies [64][65][66][67]. Examples include the assessment of hepatic metabolism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) in rats [68] or the effect of liver metabolism in inflammatory liver injury [69] and ethanol consumption as an early indicator of complications related to fatty liver disease, hepatitis, cirrhosis, and cancer [70]. Furthermore, assessment of metabolism in genetically modified knockout [71][72][73] and insulin-deficient rodent models [73][74] has been studied in detail. Like kidney, liver disease imaging is limited in human studies; however, one study has been reported on clinicaltrials.gov as “active, not recruiting” on the effect of fatty liver disease (

). Recently a novel hyperpolarized probe, [2-13C]dihydroxyacetone (DHAc), has been applied to enable estimation of liver metabolism (gluconeogenesis, glycolysis, and the glycerol pathways), and this could very well be an important finding for further clinical attention [75].

2.7. Technical Advances

2.7.1. Polarizer

Multiple methods to achieve hyperpolarization have been explored including brute force polarization, parahydrogen-induced polarization (PHIP)-based methods [76][77][78], and dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP). Currently, the only polarization process approved to be used for clinical studies of carbon-13 is DNP [1].

Brute force polarization is achieved by placing the probe in a strong magnetic field at a temperature close to 0 K [79]. While the method is straightforward to apply, it is very impractical and not useable for in vivo experiments given the temperature and very long T1 times in the solid state.

PHIP utilizes the change in parahydrogen and orthohydrogen spin states at low temperatures. Hydrogen molecules exists in two energy states—parahydrogen and orthohydrogen. At room temperature the spin states are 25% parahydrogen and 75% orthohydrogen; however, the spin states are almost complete parahydrogen (>99%) at very low temperatures (<20 K). Applying a catalyst, such as alkenes, breaks the symmetry of hydrogen, inducing a change in the spin order, known as PHIP [80]. Transfer of the polarization is thereafter performed by field cycling or polarization methods. PHIP has the advantage of being cheap and easy to use and allows for very rapid polarization. Several proposals to alter the PHIP process have been suggested, such as signal amplification by reversible exchange (SABRE [77]), synthesis amid the magnet bore allows dramatically enhanced nuclear alignment (SAMBADENA [78]), and PHIP by means of side arm hydrogenation (PHIP-SAH [81]). Until recently, the requirements of unsaturated precursor molecules, toxic solutions, and catalyzers have been a significant limitation for in vivo applications. However, PHIP-SAH may have found a way to overcome these limitations by using propargyl alcohol in the parahydrogen-induced polarization process.

DNP is based on the spin interaction of free electrons with nearby nuclear spins at low temperatures (<4 K). At this temperature the electrons have a low energy state and can achieve total polarization (100%). Applying irradiation with microwaves causes polarization exchange from the electrons to nearby nuclear spins. Electrons have a short T1 relaxation time causing them to return to their thermal equilibrium state and making them able to repeat the process on unpolarized nuclei. The process is repeated until a desired polarization is achieved according to the nuclei T1 relaxation time (polarization decreases in accordance with T1 relaxation time) [82].

Hyperpolarized carbon-13 using dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization was disseminated in 2003 by J. H. Ardenkjær-Larsen et al., demonstrating the so-called (“alpha” polarizer [82]). The technique was then commercialized in the form of HyperSense (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK) and as the clinical 5 T SPINLab (GE Research Circle Technology Inc., GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) [83] in 2011. Furthermore, a new commercial 6.7 T pre-clinical polarizer has been introduced—the Spin-Aligner (Polarize IVS, Frederiksberg, DK) in 2018 [84]. The effectiveness of the polarizers has increased rapidly (from 20% to 40% to 70%), and clinical systems are able to achieve polarization up to 55% [85], which is twice the polarization used in the first clinical trial [11]. However, new technological and methodological advances are still needed to improve the polarization method, especially with respect to cost effectiveness and user friendliness [1][86][87].

2.7.2. Sequences

MR spectroscopic imaging is often preferred over single voxel spectroscopy to evaluate local changes in metabolism inside the organ of interest. The dimensionality of hyperpolarized MRSI data is higher, and one must consider possible contamination of signal from nearby voxels (signal bleed) [88], B0 field inhomogeneities across the organ, and increased data acquisition time. As the hyperpolarized signal is non-recoverable, rapid sequences are paramount to ensure collection of metabolic information. The hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate MRSI experiment is composed of data in up to five dimensions (up to three spatial, one temporal, and one spectral) often leading to compromise in one or more dimensions to ensure rapid acquisition [89].

In proton MRI, a successful means of reducing acquisition time is to modify or sample fewer k-space points. These methods are, however, not directly applicable in MRSI. This is partly due to the inherent low number of sampling points, which do not introduce the required level of sparsity. Therefore, the focus of fast MRSI is on more efficient k-space sampling either as echo-planar imaging (EPI) [90] or spiral [91], radial [92], or concentric rings [93].

Fast imaging techniques can generally be grouped into three main approaches: (1) spectroscopic imaging; (2) prior knowledge model-based approaches; and (3) metabolite-specific imaging [94][95][96]. Acquisition time can be decreased with the combination of multiple receiver channel elements as in parallel imaging (SENSE [97], calibrationless [38]), compressed sensing [98][99][100][101], and multiband excitation [101][102] methods. Nevertheless, parallel imaging methods are challenging as acquisition of the needed sensitivity profiles is limited.

(1) Spectroscopic imaging includes phase-encoded chemical shift imaging (CSI). The CSI acquires a multivoxel MRS image, utilizing phase-encoding to achieve spatial resolution but at the cost of a longer acquisition time.

(2) Prior knowledge model-based approaches are a faster imaging method often combined with spectroscopic imaging. The speed comes from efficient acquisition of k-space points and avoiding sampling of unnecessary signal, thereby utilizing prior knowledge of the substrates to improve temporal resolution or to reduce the required sampling matrix (SLIM [103], SLOOP [104], and SLAM [105][106]). There are several variations of the prior knowledge model-based techniques; however, recent developments with spectroscopic imaging by exploiting spatiospectral correlation (SPICE) and chemical shift encoding (CSE) could be preferred options for hyperpolarized carbon-13 MRSI.

SPICE utilizes a combination of a two acquisitions: first a set of low-spatial and high-temporal resolution data, followed by a set of high-spatial and low-temporal resolution data [107]. From the two acquisitions, high resolution spectroscopic images with an adequate spectral resolution are reconstructed [108]. The method has recently been evaluated in kidney models of mice [109]; nonetheless, results of the application of this novel technique will be interesting to follow in other organs.

CSE methods include Dixon or iterative decomposition with echo asymmetry and least squares estimation (IDEAL), which apply prior knowledge of the substrates and products [110]. CSE encodes the spectral dimension sparsely by acquiring only with a few different echo times (TEs) [111].

(3) Metabolite-specific imaging is the fastest imaging method of the three approaches, making it less sensitive to motion (shorter repetition time (TR)). However, the disadvantages are the requirement of a sparse spectrum and increased sensitivity to B0 field distortions [94]. The method rapidly acquires spectral and spatial data with frequency and slices selective RF pulses in an EPI [112] or spiral readout trajectory [48]. By exciting a single metabolite at a time and changing RF pulse resonance frequencies, dynamic datasets of desired metabolites are acquired.

2.7.3. Data Acquisition, Reconstruction, Processing, and Analysis

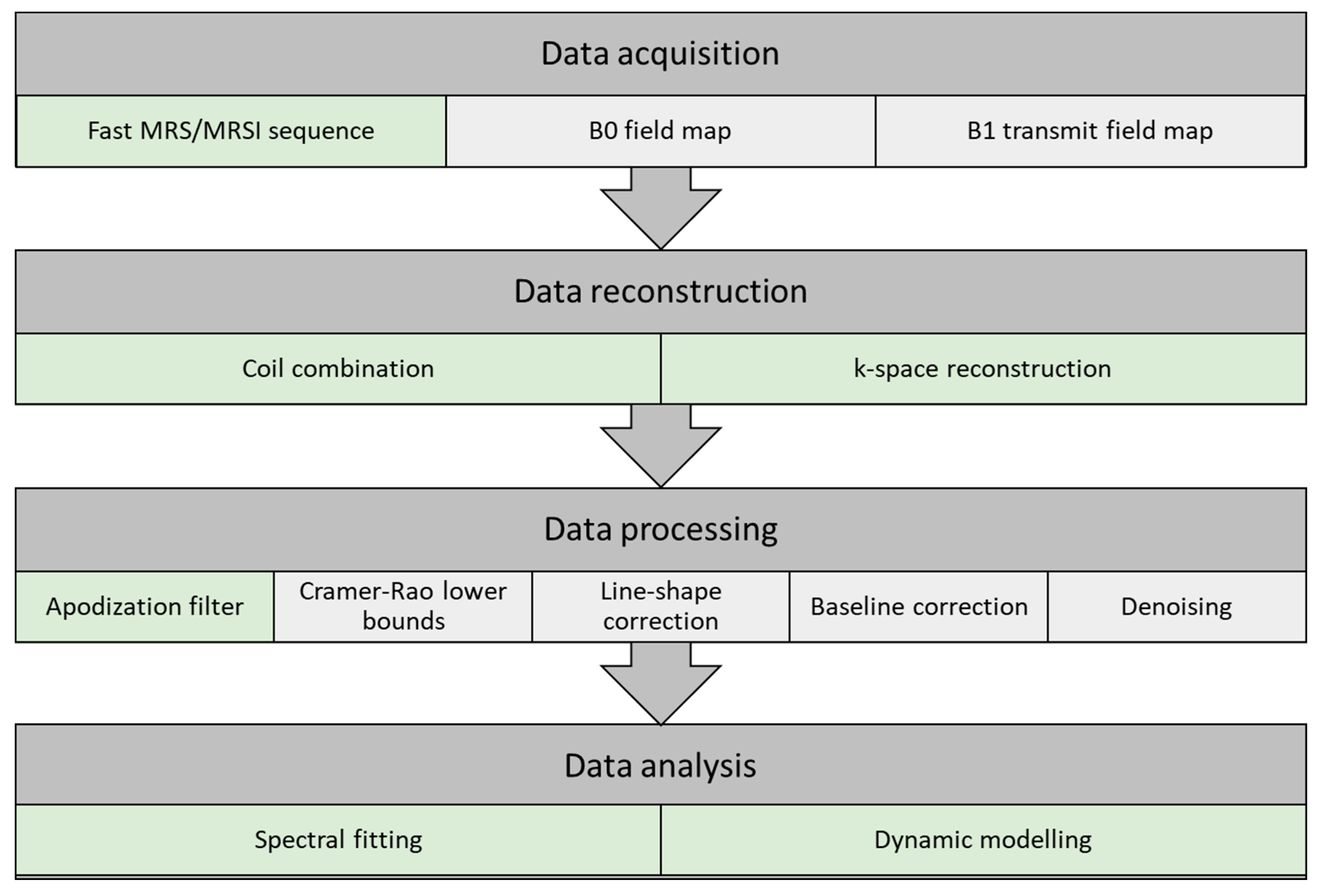

Optimized data acquisition and processing steps can be vital in the following analysis. In this section, a pipeline for data acquisition, reconstruction, processing, and analysis is described. The pipeline may vary between institutions given the selection of coils, anatomy, and sequences (e.g., 2D EPI or 3D spirals). A schematic representation of the pipeline is illustrated in

, with indication of the conventional HP

C MRI pipeline (light green) and suggestions for an extended pipeline (light grey).

Flow chart of a pipeline for data acquisition, reconstruction, processing, and analysis of hyperpolarized carbon-13 MR spectra. The pipeline illustrates the conventional approach (light green) and suggestions for extended steps (light grey).

Data Acquisition

B0 field map: Magnetic field inhomogeneity leads to a spread in resonance frequencies, causing difficulties preserving the spectral separation. The homogeneity requirements are determined by the metabolites of interest, and in HP

C MRI, good separation is achieved when the B0 homogeneity is better than Δ0.1 ppm. Improvement of B0 field homogeneity is performed by shimming. Shimming complexity increases with the size of the field of view (FOV), and larger FOVs are more prone to magnetic field irregularities. Quality of the acquired free induction decay (FID) is the basis of signal analysis accuracy. Low SNR and frequency variations reduce the quality and result in poor spectra. Signal averages and larger volumes may increase the SNR, but this can be at the cost of resolution.

B1 transmit field map: Metabolite-specific B1 mapping of the transmit field of the carbon-13 tuned transmit coil should be performed. This provides a measure to correct for possible errors in the flip angles of the sequences used in data acquisition of fast HP

C MRI sequences.

Fast MRS/MRSI sequence: A detailed description of HP

C MRI sequences is given in a previous section.

Data Reconstruction

Coil combination: Combination of multiple receiver coils may introduce phase cancelation. This can be avoided by combining the signal acquired from the coils at each voxel either by weighted sum of squares, first point phasing, or singular value decomposition methods [37].

Phase and frequency correction can be manually performed in the data processing step to accommodate for signal loss due to phase cancellation with the use of zero- and first-order phase correction. Nevertheless, several spectral fitting approaches have included phase correction as part of the data processing pipeline (OXSA-AMARES [113], JMRUI [114], and LC model [115]), alleviating this as a data processing requirement.

k-space reconstruction: MRSI trajectories (Cartesian or non-Cartesian) are applied to reconstruct the acquired MRSI to ensure correct k-space gridding. A comprehensive review of HP

C MRI sequences and reconstruction methods has recently been published by Gordon et al. [94].

Data Processing

Apodization filter: Apodization is used to enhance the SNR at the cost of spectral resolution (line broadening). The FID (time domain) or the spectra (frequency domain) is multiplied by a filter function, often an exponential function.

Cramér–Rao lower bounds: Quality assurance of the spectra can be performed by evaluation of the metabolite separation, signal-to-noise ratio, and temporal resolution. One approach is to quantitatively evaluate the SNR, spectra line width, and spectra separation with the Cramér–Rao lower bounds (CRLBs) [116][117]. CRLBs can be used as a measure to determine voxels to be included or excluded before or even after metabolite spectral fitting.

Spectral line-shape correction: Spectral fitting algorithms consist of a combination of pre-determined line shapes (Lorentzian, Gaussian, or Voigt), though acquired signal line shapes may be distorted, e.g., due to magnetic field inhomogeneities and eddy currents. Line-shape correction can be performed by deconvoluting the spectra with a reference spectrum.

Spectral baseline correction: Acquired spectra may have shifts in the baseline and thereby overestimate the metabolite resonance peaks. The spectral baseline can be corrected by applying a low-order signal fit [118]. This leads to more robust data and improved data quantification.

Denoising: Denoising has attracted great interest in HP

C MRI given the low SNR, good peak separation, and representation of metabolite peaks. Several applications of signal denoising have been evaluated for improvement of data quality, and recent applications of multidimensional tensor value decomposition show promising results by changing from a fixed rank [119] to an automatic cost function-based rank selection approach [37]. Nevertheless, denoising with the use of singular value decomposition (SVD)-based methods should be carried out with caution. The application could introduce oversimplification and thereby filter out lower SNR metabolites or disease metabolism as noise. Furthermore, if too few singular components (low rank) are used, kinetics of pyruvate could modulate the reconstructed dynamics/kinetics of the lower SNR metabolites.

Data Analysis

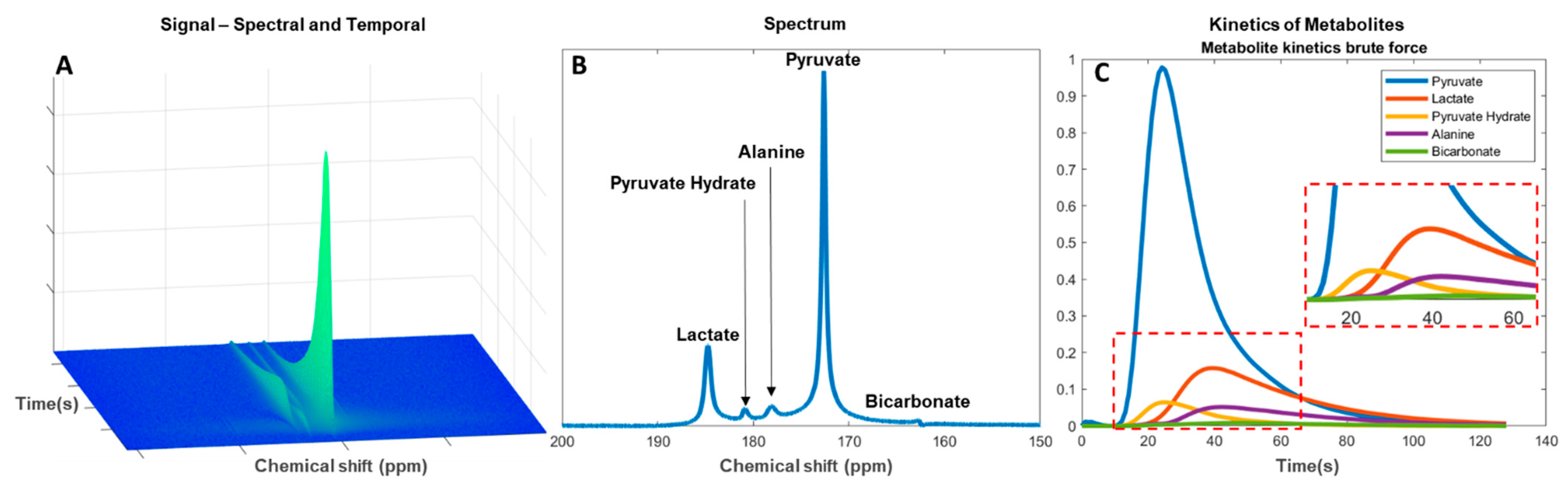

Data analysis is performed subsequent to data optimization in the acquisition and pre-processing steps. The multidimensional MRSI data consist of up to three spatial dimensions with a spectral and a temporal dimension (

A). Determination of spectral metabolites is performed by applying spectral fitting with the use of metabolite prior knowledge. The change in signal amplitudes in the temporal dimension is then used for evaluation of the metabolic flux as an estimate of the downstream metabolism from injected pyruvate to lactate, alanine, and bicarbonate (

B). Residual pyruvate may be detected in the spectrum as pyruvate hydrate. Analyses of the metabolic flux or exchange rates can be determined by fitting single-compartment or multicompartmental models. The forward rate constant of substrate conversion is calculated as an apparent conversion from pyruvate to, for example, lactate (kpl) [120][121] (

C). The results may, however, be prone to systemic errors if not combined with the pyruvate input function [122].

Analysis of hyperpolarized carbon-13 spectra from pyruvate injection. (

) Metabolite signal change in the spectral and temporal dimension since injection. (

) Total signal of downstream metabolites in a temporal summed spectrum. (

) Kinetics of the metabolites with enhanced view of smaller signal metabolites (red dashed box).

Alternatively, a model-free formulism based on the ratio of area under the curve (AUC) of the injected and downstream metabolite can be used. This has shown to be a robust and clinically relevant alternative to kinetic model-based rate measurements [123], especially in the lactate-to-pyruvate AUC ratio, which represents the full reaction as determined by compartment kinetic modelling [124]. In addition to being a simplified approach the benefit of evaluating the downstream signal of an AUC is to reduce bias in the later acquired time series [125]. In both approaches, kpl consistency should be evaluated. This could be done by only accepting kpl where the standard deviation is smaller than determined mean kpl. Furthermore, this approach may be beneficial in low SNR measurements for determination of pH from the

CO

to H

CO

2.8. Other

It is crucial for the translation of basic science to clinical application that disease models are studied meticulously to ensure high precision and diagnostic value. This methodology is applied in pre-clinical studies with the use of cell models, hyperpolarized probe testing, and validation of widespread pathologies in animal models. Expanding the understanding of disease-altered metabolism and the underlaying processes involved in interventional treatment responses is key for method validation before initiating clinical trials.

This review focuses on the clinical transition; therefore, areas other than those listed in the previous sections (e.g., lung [128][129], angiography [130], placenta [131][132], muscle [133][134][135]), diseases (e.g., diabetes [58][136][137][138], rheumatoid arthritis [139][140], toxin-induced neuroinflammation [141], radiation injury [142][143]), and physiology (e.g., cell metabolism [144][145], pH [126], blood serum [146][147], bacteria metabolism [148]) are not be covered.

2.9. Clinical Transition

Hyperpolarized MRI is on the verge of clinical translation [27]; however; to ensure clinical adaptation, it is important to improve and validate the workflow. As of today, 50 polarizers prepared for injection into humans are installed worldwide [3], and more than 10 sites are performing clinical trials. More than 200 human subjects have participated in clinical trials with HP

C MRI [27].

As of today, 17 clinical studies have been conducted (

). The number of clinical studies is not a direct measure of the translational state; however, it does indicate the activities and research focuses of the hyperpolarized carbon-13 research community. Evaluating studies reported to clinicaltrials.gov as “active, not recruiting” or “recruiting” indicates that the field is pointing towards increase in clinical trials and covering a wider area of diseases. The number of clinical trials is set to double, with 27 new studies imminent (

).

Overview of applications for which clinical trials have been performed with hyperpolarized carbon-13 MRI and their translation state towards clinical adaption.

| Area of Interest | Publications | Human Trials | Translation State |

|---|

| Title | Condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology | 170 | prostate: [7,[20,22,1123,24]][12][14][15][16] pancreas: [27][19], breast: [28,29][20][21], brain: [9,20,32,153][23][12][25][149], kidney: [33][26] |

High |

| Brain | 37 | [8,13,46][2][4][40] | Low |

| Heart | 87 | [5,54][48][49] | Medium |

| Kidney | 31 | - | Low |

| Liver | 21 | - | Low |

| Technical advances 1 | 349 | - | - |

| Other 2 | 118 | - | - |

The database of interventional clinical trials with medical products in the European Union, EudraCT (European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials Database), lists an additional six HP

C MRI studies, three of which were initiated during 2020 (

).

The determination of the translational state is based on subjective measures rather than a systematic meta-analysis of the relatively low number of studies performed on a low number of subjects. Clinical transition occurs when a novel or improved diagnostic measure is needed. If conventional methods are superior, transition often does not occur. With this in mind, we focus on the translational state of five selected areas, highlighted in

, and outline a qualified estimate of which will become a clinical application first.

Cardiac HP

C MRI has been performed in clinical studies [48][49], while no kidney or liver studies have so far been published (excluding renal cancer). Three brain studies have been reported in the recent years on healthy brain [2][4][40]; however, none are reporting metabolic changes due to pathology. Therefore, we consider the current translational state of the four areas to be low to medium.

HP

C MRI in cancer models has proven great potential, not only from the clinical trials but also from the possibilities of targeting cancer cell models in advanced experimental studies [27]. This provides a measure of going from specific cell culture analysis in small animal models to clinical trials with accurate and reproducible results. Transition from research to clinical implementation is plausible in prostate cancer given the large number of studies performed since the first clinical trial in 2013. Nevertheless, it has recently been proposed that there could be an even greater advantage of the application in breast cancer, potentially reducing the number treatments and treatment time (today approximately 12 treatments in 3 months) [150]. The level of detail and experience of HP

C MRI in oncology is providing assurance of the value in the method; therefore, we consider the current translational state to be high.

Studies reported to clinicaltrials.gov as “active, not recruiting” or “recruiting” on hyperpolarized carbon-13 MRI.

| Title | Condition | Trial Number |

|---|

| EudraCT Number | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pilot Study of Safety and Toxicity of Acquiring Hyperpolarized Carbon-13 Imaging in Children With Brain Tumors | Pediatric brain tumors | NCT02947373 |

| 2 | Hyperpolarized Carbon-13 Imaging of Metastatic Prostate Cancer |

| 1 | |||||||

| Prostate cancer | NCT02844647 | ||||||

| Early detection of effects of chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer patients—a study using MR-hyperpolarization scanning based on hyperpolarized Pyruvate (13C) injection | Pancreatic cancer | 2016-004491-22 | 3 | Imaging of Traumatic Brain Injury Metabolism Using Hyperpolarized Carbon-13 Pyruvate | |||

| 2 | Traumatic brain injury | NCT03502967 | |||||

| MRI of neurometabolic impairment in ALS and TIA using hyperpolarized pyruvate | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 2020-000352-36 | 4 | Metabolic Characteristics of Brain Tumors Using Hyperpolarized Carbon-13 Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging (MRSI) | |||

| 3 | Brain tumor adult | ||||||

| 4 | MRI with hyperpolarised pyruvate in glioblastoma—a phase II study | NCT03067467 | |||||

| Glioblastoma multiforme | 2020-000310-15 | 5 | Hyperpolarized Carbon 13-Based Metabolic Imaging to Detect Radiation-Induced Cardiotoxicity | Thoracic cancer/left sided breast cancer | NCT04044872 | ||

| 5 | Metabolic imaging of patients with mycosis fungoides using hyperpolarized 13C-Pyruvate magnetic resonance imaging—A feasibility study | Mycosis fungoides | 2018-001656-35 | 6 | Hyperpolarized Carbon-13 (13C) Pyruvate Imaging in Patients With Glioblastoma | Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) | NCT04019002 |

| 7 | Hyperpolarized 13C Pyruvate MRI for Treatment Response Assessment in Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | NCT04565327 | ||||

| 8 | Feasibility of Acquiring Hyperpolarized Imaging in Patients With Primary CNS Lymphoma | Primary CNS lymphoma | NCT04656431 | ||||

| 9 | Effect of Cardiotoxic Anticancer Chemotherapy on the Metabolism of [1-13C]Pyruvate in Cardiac Mitochondria | Breast neoplasms | NCT03685175 | ||||

| 10 | Hyperpolarized Carbon C 13 Pyruvate Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging in Predicting Treatment Response in Patients With Prostate Cancer | Prostate cancer | NCT03581500 | ||||

| 11 | Hyperpolarized 13C Pyruvate MRI Scan in Predicting Tumor Aggressiveness in Patients With Localized Renal Tumor | Benign kidney cancer | NCT04258462 | ||||

| 12 | Hyperpolarized Pyruvate (13C) MR Imaging in Monitoring Patients With Prostate Cancer on Active Surveillance | Prostate adenocarcinoma | NCT03933670 | ||||

| 13 | Hyperpolarized Carbon C 13 Pyruvate in Diagnosing Glioma in Patients With Brain Tumors | Primary brain neoplasm | NCT03830151 | ||||

| 14 | Serial MR Imaging and MR Spectroscopic Imaging for the Characterization of Lower Grade Glioma | Glioma | NCT04540107 | ||||

| 6 | A Dose-Ranging Pharmacodynamic Study to Evaluate the Effects of IMB-1018972 on Myocardial Energetics, Metabolism, and Function in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes | Diabetic cardiomyopathy | 2020-003280-26 | 15 | Hyperpolarized 13C MR Imaging of Lactate in Patients With Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer (LACC) Cervical Cancer | Uterine cervical neoplasms | NCT03129776 |

| 16 | Role of Hyperpolarized 13C-Pyruvate MR Spectroscopy in Patients With Intracranial Metastasis Treated With (SRS) | Brain metastases | NCT03324360 | ||||

| 17 | Hyperpolarized Imaging in Diagnosing Participants With Glioma | Glioma | NCT03739411 | ||||

| 18 | Metabolic Imaging of the Heart Using Hyperpolarized (13C) Pyruvate Injection | Hypertension/hypertrophy | NCT02648009 | ||||

| 19 | Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) With Hyperpolarized Pyruvate (13C) as Diagnostic Tool in Advanced Prostate Cancer | Prostate cancer | NCT04346225 | ||||

| 20 | Imaging Oxidative Metabolism and Neurotransmitter Synthesis in the Human Brain | Brain cancer | NCT03849963 | ||||

| 21 | Study to Evaluate the Feasibility of 13-C Pyruvate Imaging in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | Breast cancer | NCT03121989 | ||||

| 22 | Development and Evaluation of a Quantitative HP MRI for Clinical Prostate Cancer Exam | Prostate adenocarcinoma | NCT04286386 | ||||

| 23 | A Pilot Study of (MR) Imaging With Pyruvate (13C) to Detect High Grade Prostate Cancer | Prostate cancer | NCT02526368 | ||||

| 24 | An Investigational Scan (hpMRI) for Monitoring Treatment Response in Patients With Thyroid Cancer Undergoing Radiation Therapy and/or Systemic Therapy | Thyroid gland carcinoma | NCT04589624 | Fatty liver | NCT03480594 | ||

| Clinical and pathophysiological aspects of visualization of metabolic flux in the failing human heart using hyperpolarized [1-13C]-pyruvate cardiac magnetic resonance | Chronic heart failure | 2018-003533-15 | |||||

| 25 | Effect of Fatty Liver on TCA Cycle Flux and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway | 26 | Hyperpolarized C-13 Pyruvate as a Biomarker in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumor Malignancies | Prostate cancer | NCT02913131 | ||

| 27 | Characterization of Hyperpolarized Pyruvate MRI Reproducibility | Malignant solid tumors | NCT02421380 |

Studies reported to EudraCT for clinical trials of hyperpolarized carbon-13 MRI.

References

- Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H. On the present and future of dissolution-DNP. J. Magn. Reson. 2016, 264, 3–12.

- Lee, C.Y.; Soliman, H.; Geraghty, B.J.; Chen, A.P.; Connelly, K.A.; Endre, R.; Perks, W.J.; Heyn, C.; Black, S.E.; Cunningham, C.H. Lactate topography of the human brain using hyperpolarized 13C-MRI. NeuroImage 2020, 78, 3755–3760.

- Wang, Z.J.; Ohliger, M.A.; Larson, P.E.Z.; Gordon, J.W.; Bok, R.A.; Slater, J.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; Hess, C.P.; Kurhanewicz, J.; Vigneron, D.B. Hyperpolarized 13C MRI: State of the Art and Future Directions. Radiology 2019, 291, 273–284.

- Grist, J.T.; McLean, M.A.; Riemer, F.; Schulte, R.F.; Deen, S.S.; Zaccagna, F.; Woitek, R.; Daniels, C.J.; Kaggie, J.D.; Matys, T.; et al. Quantifying normal human brain metabolism using hyperpolarized [1–13C]pyruvate and magnetic resonance imaging. NeuroImage 2019, 189, 171–179.

- Keshari, K.R.; Wilson, D.M. Chemistry and biochemistry of 13C hyperpolarized magnetic resonance using dynamic nuclear polarization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1627–1659.

- Grist, J.T.; Miller, J.J.; Zaccagna, F.; McLean, M.A.; Riemer, F.; Matys, T.; Tyler, D.J.; Laustsen, C.; Coles, A.J.; Gallagher, F.A. Hyperpolarized 13C MRI: A novel approach for probing cerebral metabolism in health and neurological disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 40, 1137–1147.

- Warburg, O. On the Origin of Cancer Cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314.

- Zaccagna, F.; Grist, J.T.; Deen, S.S.; Woitek, R.; Lechermann, L.M.; McLean, M.A.; Basu, B.; Gallagher, F.A. Hyperpolarized carbon-13 magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging: A clinical tool for studying tumour metabolism. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20170688.

- Heiden, M.G.V.; Cantley, L.C.; Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 2009, 324, 1029–1033.

- Golman, K.; Lerche, M.; Pehrson, R.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H. Metabolic Imaging by Hyperpolarized 13C Magnetic Resonance Imaging for In vivo Tumor Diagnosis. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10855–10860.

- Nelson, S.J.; Kurhanewicz, J.; Vigneron, D.B.; Larson, P.E.Z.; Harzstark, A.L.; Ferrone, M.; Van Criekinge, M.; Chang, J.W.; Bok, R.; Park, I.; et al. Metabolic Imaging of Patients with Prostate Cancer Using Hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyruvate. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 198ra108.

- Gordon, J.W.; Chen, H.-Y.; Autry, A.; Park, I.; Van Criekinge, M.; Mammoli, D.; Milshteyn, E.; Bok, R.; Xu, D.; Li, Y.; et al. Translation of Carbon-13 EPI for hyperpolarized MR molecular imaging of prostate and brain cancer patients. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019, 81, 2702–2709.

- Kurhanewicz, J.; Bok, R.; Nelson, S.J.; Vigneron, D.B. Current and Potential Applications of Clinical 13C MR Spectroscopy. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 49, 341–344.

- Chen, H.-Y.; Aggarwal, R.; Bok, R.A.; Ohliger, M.A.; Zhu, Z.; Lee, P.; Gordon, J.W.; Van Criekinge, M.; Carvajal, L.; Slater, J.B.; et al. Hyperpolarized 13C-pyruvate MRI detects real-time metabolic flux in prostate cancer metastases to bone and liver: A clinical feasibility study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020, 23, 269–276.

- Aggarwal, R.; Vigneron, D.B.; Kurhanewicz, J. Hyperpolarized 1-[13C]-Pyruvate Magnetic Resonance Imaging Detects an Early Metabolic Response to Androgen Ablation Therapy in Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2017, 72, 1028–1029.

- Barrett, T.; Riemer, F.; McLean, M.A.; Kaggie, J.D.; Robb, F.; Warren, A.Y.; Graves, M.J.; Gallagher, F.A. Molecular imaging of the prostate: Comparing total sodium concentration quantification in prostate cancer and normal tissue using dedicated 13C and 23Na endorectal coils. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020, 51, 90–97.

- Kurhanewicz, J.; Vigneron, D.B. Advances in MR Spectroscopy of the Prostate. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. North Am. 2008, 16, 697–710.

- Wilson, D.M.; Kurhanewicz, J. Hyperpolarized 13C MR for Molecular Imaging of Prostate Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 1567–1572.

- Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H.; Laustsen, C.; Hansen, E.S.S.; Schulte, R.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Comment, A.; Frøkiær, J.; Ringgaard, S.; Bertelsen, L.B.; Ladekarl, M.; et al. Pilot Study Experiences With Hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate MRI in Pancreatic Cancer Patients. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020, 51, 961–963.

- Gallagher, F.A.; Woitek, R.; McLean, M.A.; Gill, A.B.; Garcia, R.M.; Provenzano, E.; Riemer, F.; Kaggie, J.; Chhabra, A.; Ursprung, S.; et al. Imaging breast cancer using hyperpolarized carbon-13 MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 2092–2098.

- Woitek, R.; McLean, M.A.; Gill, A.B.; Grist, J.T.; Provenzano, E.; Patterson, A.J.; Ursprung, S.; Torheim, T.; Zaccagna, F.; Locke, M.; et al. Hyperpolarized 13C MRI of Tumor Metabolism Demonstrates Early Metabolic Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 2020, 2, e200017.

- Jagannathan, N.R. Application of in vivo MR methods in the study of breast cancer metabolism. NMR Biomed. 2019, 32, e4032.

- Miloushev, V.Z.; Granlund, K.L.; Boltyanskiy, R.; Lyashchenko, S.K.; DeAngelis, L.M.; Mellinghoff, I.K.; Brennan, C.W.; Tabar, V.; Yang, T.J.; Holodny, A.I.; et al. Metabolic Imaging of the Human Brain with Hyperpolarized 13C Pyruvate Demonstrates 13C Lactate Production in Brain Tumor Patients. Cancer Res. 2018, 256, 36–42.

- Zhu, X.; Gordon, J.W.; Bok, R.A.; Kurhanewicz, J.; Larson, P.E. Dynamic diffusion-weighted hyperpolarized 13C imaging based on a slice-selective double spin echo sequence for measurements of cellular transport. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019, 81, 2001–2010.

- Autry, A.W.; Gordon, J.W.; Chen, H.-Y.; Lafontaine, M.; Bok, R.; Van Criekinge, M.; Slater, J.B.; Carvajal, L.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; Chang, S.M.; et al. Characterization of serial hyperpolarized 13C metabolic imaging in patients with glioma. NeuroImage Clin. 2020, 27, 102323.

- Tran, M.; Latifoltojar, A.; Neves, J.B.; Papoutsaki, M.-V.; Gong, F.; Comment, A.; Costa, A.S.H.; Glaser, M.; Tran-Dang, M.-A.; El Sheikh, S.; et al. First-in-human in vivo non-invasive assessment of intra-tumoral metabolic heterogeneity in renal cell carcinoma. BJR Case Rep. 2019, 5, 20190003.

- Kurhanewicz, J.; Vigneron, D.B.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Bankson, J.A.; Brindle, K.; Cunningham, C.H.; Gallagher, F.A.; Keshari, K.R.; Kjaer, A.; Laustsen, C.; et al. Hyperpolarized 13C MRI: Path to Clinical Translation in Oncology. Neoplasia 2019, 21, 1–16.

- Guglielmetti, C.; Najac, C.; Didonna, A.; Van Der Linden, A.; Ronen, S.M.; Chaumeil, M.M. Hyperpolarized 13C MR metabolic imaging can detect neuroinflammation in vivo in a multiple sclerosis murine model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6982–E6991.

- Xu, Y.; Ringgaard, S.; Mariager, C.Ø.; Bertelsen, L.B.; Schroeder, M.; Qi, H.; Laustsen, C.; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H. Hyperpolarized 13C Magnetic Resonance Imaging Can Detect Metabolic Changes Characteristic of Penumbra in Ischemic Stroke. Tomography 2017, 3, 67–73.

- Stovell, M.G.; Yan, J.-L.; Sleigh, A.; Mada, M.O.; Carpenter, T.A.; Hutchinson, P.J.A.; Carpenter, K.L.H. Assessing Metabolism and Injury in Acute Human Traumatic Brain Injury with Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy: Current and Future Applications. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8.

- DeVience, S.J.; Lu, X.; Proctor, J.; Rangghran, P.; Melhem, E.R.; Gullapalli, R.; Fiskum, G.M.; Mayer, D. Metabolic imaging of energy metabolism in traumatic brain injury using hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–7.

- Guglielmetti, C.; Chou, A.; Krukowski, K.; Najac, C.; Feng, X.; Riparip, L.-K.; Rosi, S.; Chaumeil, M.M. In vivo metabolic imaging of Traumatic Brain Injury. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17525.

- Takado, Y.; Cheng, T.; Bastiaansen, J.A.M.; Yoshihara, H.A.I.; Lanz, B.; Mishkovsky, M.; Lengacher, S.; Comment, A. Hyperpolarized 13C Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Reveals the Rate-Limiting Role of the Blood–Brain Barrier in the Cerebral Uptake and Metabolism of l-Lactate in Vivo. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 2554–2562.

- Miller, J.J.; Grist, J.T.; Serres, S.; Larkin, J.R.; Lau, A.Z.; Ray, K.; Fisher, K.R.; Hansen, E.; Tougaard, R.S.; Nielsen, P.M.; et al. 13C Pyruvate Transport Across the Blood-Brain Barrier in Preclinical Hyperpolarised MRI. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–15.

- Josan, S.; Hurd, R.E.; Billingsley, K.L.; Senadheera, L.; Park, J.M.; Yen, Y.-F.; Pfefferbaum, A.; Spielman, D.M.; Mayer, D. Effects of isoflurane anesthesia on hyperpolarized 13C metabolic measurements in rat brain. Magn. Reson. Med. 2013, 70, 1117–1124.

- Lee, J.; Ramirez, M.S.; Walker, C.M.; Chen, Y.; Yi, S.; Sandulache, V.C.; Lai, S.Y.; Bankson, J.A. High-throughput hyperpolarized 13 C metabolic investigations using a multi-channel acquisition system. J. Magn. Reson. 2015, 260, 20–27.

- Chen, H.; Autry, A.W.; Brender, J.R.; Kishimoto, S.; Krishna, M.C.; Vareth, M.; Bok, R.A.; Reed, G.D.; Carvajal, L.; Gordon, J.W.; et al. Tensor image enhancement and optimal multichannel receiver combination analyses for human hyperpolarized 13 C MRSI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2020, 84, 3351–3365.

- Gordon, J.W.; Hansen, R.B.; Shin, P.J.; Feng, Y.; Vigneron, D.B.; Larson, P.E. 3D hyperpolarized C-13 EPI with calibrationless parallel imaging. J. Magn. Reson. 2018, 289, 92–99.

- Nelson, S.J.; Ozhinsky, E.; Li, Y.; Park, I.W.; Crane, J. Strategies for rapid in vivo 1H and hyperpolarized 13C MR spectroscopic imaging. J. Magn. Reson. 2013, 229, 187–197.

- Chung, B.T.; Chen, H.-Y.; Gordon, J.; Mammoli, D.; Sriram, R.; Autry, A.W.; Le Page, L.M.; Chaumeil, M.M.; Shin, P.; Slater, J.; et al. First hyperpolarized [2-13C]pyruvate MR studies of human brain metabolism. J. Magn. Reson. 2019, 309, 106617.

- Captur, G.; Manisty, C.; Moon, J.C. Cardiac MRI evaluation of myocardial disease. Heart 2016, 102, 1429–1435.

- Neubauer, S. The Failing Heart—An Engine Out of Fuel. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1140–1151.

- Schroeder, M.A.; Clarke, K.; Neubauer, S.; Tyler, D.J. Hyperpolarized Magnetic Resonance: A Novel Technique for the In Vivo Assessment of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2011, 124, 1580–1594.

- Rider, O.J.; Tyler, D.J. Clinical Implications of Cardiac Hyperpolarized Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2013, 15, 93.

- Lauritzen, M.; Sogaard, L.; Madsen, P.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J. Hyperpolarized Metabolic MR in the Study of Cardiac Function and Disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 6162–6170.

- Lau, A.Z.; Lau, J.Y.C.; Chen, A.P.; Cunningham, C.H. Simultaneous multislice acquisition without trajectory modification for hyperpolarized 13 C experiments. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018, 80, 1588–1594.

- Dominguez, W.; Geraghty, B.J.; Lau, J.Y.; Robb, F.J.; Chen, A.P.; Cunningham, C.H. Intensity correction for multichannel hyperpolarized 13 C imaging of the heart. Magn. Reson. Med. 2015, 75, 859–865.

- Cunningham, C.H.; Lau, J.Y.; Chen, A.P.; Geraghty, B.J.; Perks, W.J.; Roifman, I.; Wright, G.A.; Connelly, K.A. Hyperpolarized 13C Metabolic MRI of the Human Heart. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 1177–1182.

- Rider, O.J.; Apps, A.; Miller, J.J.; Lau, J.Y.; Lewis, A.J.; Peterzan, M.A.; Dodd, M.S.; Lau, A.Z.; Trumper, C.; Gallagher, F.A.; et al. Noninvasive In Vivo Assessment of Cardiac Metabolism in the Healthy and Diabetic Human Heart Using Hyperpolarized 13 C MRI. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 725–736.

- Lewis, A.J.M.; Tyler, D.J.; Rider, O. Clinical Cardiovascular Applications of Hyperpolarized Magnetic Resonance. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2020, 34, 231–240.

- Dekkers, I.A.; De Boer, A.; Sharma, K.; Cox, E.F.; Lamb, H.J.; Buckley, D.L.; Bane, O.; Morris, D.M.; Prasad, P.V.; Semple, S.I.K.; et al. Consensus-based technical recommendations for clinical translation of renal T1 and T2 mapping MRI. Magma Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2020, 33, 163–176.

- Mendichovszky, I.; Pullens, P.; Dekkers, I.; Nery, F.; Bane, O.; Pohlmann, A.; De Boer, A.; Ljimani, A.; Odudu, A.; Buchanan, C.; et al. Technical recommendations for clinical translation of renal MRI: A consensus project of the Cooperation in Science and Technology Action PARENCHIMA. Magma Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2020, 33, 131–140.

- Laustsen, C. Hyperpolarized Renal Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Potential and Pitfalls. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 72.

- Johansson, E.; Olsson, L.E.; Månsson, S.; Petersson, J.; Golman, K.; Ståhlberg, F.; Wirestam, R. Perfusion assessment with bolus differentiation: A technique applicable to hyperpolarized tracers. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004, 52, 1043–1051.

- Golman, K.; Petersson, J.S. Metabolic Imaging and Other Applications of Hyperpolarized 13C1. Acad. Radiol. 2006, 13, 932–942.

- Laustsen, C.; Østergaard, J.A.; Lauritzen, M.H.; Nørregaard, R.; Bowen, S.; Søgaard, L.V.; Flyvbjerg, A.; Pedersen, M.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H. Assessment of early diabetic renal changes with hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2013, 29, 125–129.

- Grobner, T. Gadolinium—A specific trigger for the development of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2006, 21, 1104–1108.

- Keshari, K.R.; Wilson, D.M.; Sai, V.; Bok, R.; Jen, K.-Y.; Larson, P.; Van Criekinge, M.; Kurhanewicz, J.; Wang, Z.J. Noninvasive In Vivo Imaging of Diabetes-Induced Renal Oxidative Stress and Response to Therapy Using Hyperpolarized 13C Dehydroascorbate Magnetic Resonance. Diabetes 2015, 64, 344–352.

- Laustsen, C.; Lycke, S.; Palm, F.; Østergaard, J.A.; Bibby, B.M.; Nørregaard, R.; Flyvbjerg, A.; Pedersen, M.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Ardenkjær-Larsen, J.H. High altitude may alter oxygen availability and renal metabolism in diabetics as measured by hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate magnetic resonance imaging. Kidney Int. 2014, 86, 67–74.

- Baligand, C.; Qin, H.; True-Yasaki, A.; Gordon, J.W.; Von Morze, C.; Santos, J.D.; Wilson, D.M.; Raffai, R.; Cowley, P.M.; Baker, A.J.; et al. Hyperpolarized13C magnetic resonance evaluation of renal ischemia reperfusion injury in a murine model. NMR Biomed. 2017, 30, e3765.

- Reed, G.D.; Von Morze, C.; Bok, R.; Koelsch, B.L.; Van Criekinge, M.; Smith, K.J.; Larson, P.E.Z.; Kurhanewicz, J.; Vigneron, D.B.; Shang, H. High resolution (13)C MRI with hyperpolarized urea: In vivo T(2) mapping and (15)N labeling effects. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2013, 33, 362–371.

- Pedersen, M.; Ursprung, S.; Jensen, J.D.; Jespersen, B.; Gallagher, F.; Laustsen, C. Hyperpolarised 13C-MRI metabolic and functional imaging: An emerging renal MR diagnostic modality. Magma: Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2019, 33, 23–32.

- Durst, M.; Chiavazza, E.; Haase, A.; Aime, S.; Schwaiger, M.; Schulte, R.F. α-trideuteromethyl[15N]glutamine: A long-lived hyperpolarized perfusion marker. Magn. Reson. Med. 2016, 76, 1900–1904.

- Ohliger, M.A.; Von Morze, C.; Marco-Rius, I.; Gordon, J.; Larson, P.E.Z.; Bok, R.; Chen, H.-Y.; Kurhanewicz, J.; Vigneron, D. Combining hyperpolarized 13C MRI with a liver-specific gadolinium contrast agent for selective assessment of hepatocyte metabolism. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017, 77, 2356–2363.

- Moreno, K.X.; Satapati, S.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Burgess, S.C.; Malloy, C.R.; Merritt, M.E. Real-time Detection of Hepatic Gluconeogenic and Glycogenolytic States Using Hyperpolarized [2-13C]Dihydroxyacetone. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 35859–35867.

- Moon, C.-M.; Shin, S.-S.; Lim, N.-Y.; Kim, S.-K.; Kang, Y.-J.; Kim, H.-O.; Lee, S.-J.; Beak, B.-H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Jeong, G.-W. Metabolic alterations in a rat model of hepatic ischaemia reperfusion injury: In vivo hyperpolarized 13 C MRS and metabolic imaging. Liver Int. 2018, 38, 1117–1127.

- Moon, C.-M.; Shin, S.-S.; Heo, S.-H.; Lim, H.-S.; Moon, M.-J.; Surendran, S.P.; Kim, G.-E.; Park, I.-W.; Jeong, Y.-Y. Metabolic Changes in Different Stages of Liver Fibrosis: In vivo Hyperpolarized 13C MR Spectroscopy and Metabolic Imaging. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2019, 21, 842–851.

- Moon, C.-M.; Oh, C.-H.; Ahn, K.-Y.; Yang, J.-S.; Kim, J.-Y.; Shin, S.-S.; Lim, H.-S.; Heo, S.-H.; Seon, H.-J.; Kim, J.-W.; et al. Metabolic biomarkers for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by high-fat diet: In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy of hyperpolarized [1-13C] pyruvate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 112–119.

- Josan, S.; Billingsley, K.L.; Orduna, J.; Park, J.M.; Luong, R.; Yu, L.; Hurd, R.E.; Pfefferbaum, A.; Spielman, D.M.; Mayer, D. Assessing inflammatory liver injury in an acute CCl4model using dynamic 3D metabolic imaging of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate. NMR Biomed. 2015, 28, 1671–1677.

- Spielman, D.M.; Mayer, D.; Yen, Y.-F.; Tropp, J.; Hurd, R.E.; Pfefferbaum, A. In vivo measurement of ethanol metabolism in the rat liver using magnetic resonance spectroscopy of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate. Magn. Reson. Med. 2009, 62, 307–313.

- Jin, E.S.; Moreno, K.X.; Wang, J.; Fidelino, L.; Merritt, M.E.; Sherry, A.D.; Malloy, C.R. Metabolism of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate through alternate pathways in rat liver. NMR Biomed. 2016, 29, 466–474.

- Sharma, G.; Wu, C.-Y.; Wynn, R.M.; Gui, W.; Malloy, C.R.; Sherry, A.D.; Chuang, D.T.; Khemtong, C. Real-time hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance detects increased pyruvate oxidation in pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 2/4–double knockout mouse livers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11.

- Høyer, K.F.; Laustsen, C.; Ringgaard, S.; Qi, H.; Mariager, C.Ø.; Nielsen, T.S.; Sundekilde, U.K.; Treebak, J.T.; Jessen, N.; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H. Assessment of mouse liver [1-13C]pyruvate metabolism by dynamic hyperpolarized MRS. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 242, 251–260.

- Lee, P.; Leong, W.; Tan, T.; Lim, M.; Han, W.; Radda, G.K. In Vivohyperpolarized carbon-13 magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals increased pyruvate carboxylase flux in an insulin-resistant mouse model. Hepatology 2013, 57, 515–524.

- Marco-Rius, I.; Wright, A.J.; Hu, D.-E.; Savic, D.; Miller, J.J.; Timm, K.N.; Tyler, D.; Brindle, K.M.; Comment, A. Probing hepatic metabolism of [2-13C]dihydroxyacetone in vivo with 1H-decoupled hyperpolarized 13C-MR. Magma Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2021, 34, 49–56.

- Hövener, J.-B.; Chekmenev, E.Y.; Harris, K.C.; Perman, W.H.; Tran, T.T.; Ross, B.D.; Bhattacharya, P. Quality assurance of PASADENA hyperpolarization for 13C biomolecules. Magma Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2008, 22, 123–134.

- Lehmkuhl, S.; Suefke, M.; Kentner, A.; Yen, Y.-F.; Blümich, B.; Rosen, M.S.; Appelt, S.; Theis, T. SABRE polarized low field rare-spin spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 184202.

- Berner, S.; Schmidt, A.B.; Zimmermann, M.; Pravdivtsev, A.N.; Glöggler, S.; Hennig, J.; Von Elverfeldt, D.; Hövener, J. SAMBADENA Hyperpolarization of 13C-Succinate in an MRI: Singlet-Triplet Mixing Causes Polarization Loss. ChemistryOpen 2019, 8, 728–736.

- Hirsch, M.L.; Kalechofsky, N.; Belzer, A.; Rosay, M.; Kempf, J.G. Brute-Force Hyperpolarization for NMR and MRI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8428–8434.

- Duckett, S.B.; Mewis, R.E. Application of Parahydrogen Induced Polarization Techniques in NMR Spectroscopy and Imaging. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1247–1257.

- Reineri, F.; Boi, T.; Aime, S. ParaHydrogen Induced Polarization of 13C carboxylate resonance in acetate and pyruvate. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5858.

- Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Fridlund, B.; Gram, A.; Hansson, L.; Lerche, M.H.; Servin, R.; Thaning, M.; Golman, K. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of >10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10158–10163.

- Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Leach, A.M.; Clarke, N.; Urbahn, J.; Anderson, D.; Skloss, T.W. Dynamic nuclear polarization polarizer for sterile use intent. NMR Biomed. 2011, 24, 927–932.

- Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Bowen, S.; Petersen, J.R.; Rybalko, O.; Vinding, M.S.; Ullisch, M.; Nielsen, N.C. Cryogen-free dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization polarizer operating at 3.35 T, 6.70 T, and 10.1 T. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019, 81, 2184–2194.

- Cheng, T.; Gaunt, A.P.; Marco-Rius, I.; Gehrung, M.; Chen, A.P.; Van Der Klink, J.J.; Comment, A. A multisample 7 T dynamic nuclear polarization polarizer for preclinical hyperpolarized MR. NMR Biomed. 2020, 33, e4264.

- Pinon, A.C.; Capozzi, A.; Ardenkjær-Larsen, J.H. Hyperpolarization via dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization: New technological and methodological advances. Magma Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2021, 34, 5–23.

- Hurd, R.E.; Yen, Y.-F.; Chen, A.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H. Hyperpolarized13C metabolic imaging using dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 36, 1314–1328.

- Maudsley, A. Sensitivity in fourier imaging. J. Magn. Reson. 1986, 68, 363–366.

- Golman, K.; Thaning, M. Real-time metabolic imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11270–11275.

- Yen, Y.-F.; Kohler, S.; Chen, A.; Tropp, J.; Bok, R.; Wolber, J.; Albers, M.; Gram, K.; Zierhut, M.; Park, I.; et al. Imaging considerations for in vivo13C metabolic mapping using hyperpolarized13C-pyruvate. Magn. Reson. Med. 2009, 62, 1–10.

- Mayer, D.; Levin, Y.S.; Hurd, R.E.; Glover, G.H.; Spielman, D.M. Fast metabolic imaging of systems with sparse spectra: Application for hyperpolarized13C imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006, 56, 932–937.

- Ramirez, M.S.; Lee, J.; Walker, C.M.; Sandulache, V.C.; Hennel, F.; Lai, S.Y.; Bankson, J.A. Radial spectroscopic MRI of hyperpolarized [1-13C] pyruvate at 7 tesla. Magn. Reson. Med. 2014, 72, 986–995.

- Jiang, W.; Lustig, M.; Larson, P.E.Z. Concentric rings K-space trajectory for hyperpolarized 13C MR spectroscopic imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2016, 75, 19–31.

- Gordon, J.W.; Chen, H.; Dwork, N.; Tang, S.; Larson, P.E.Z. Fast Imaging for Hyperpolarized MR Metabolic Imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2021, 53, 686–702.

- Schulte, R.F.; Sperl, J.I.; Weidl, E.; Menzel, M.I.; Janich, M.A.; Khegai, O.; Durst, M.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Glaser, S.J.; Haase, A.; et al. Saturation-recovery metabolic-exchange rate imaging with hyperpolarized [1-13C] pyruvate using spectral-spatial excitation. Magn. Reson. Med. 2012, 69, 1209–1216.

- Cunningham, C.H.; Chen, A.P.; Lustig, M.; Hargreaves, B.A.; Lupo, J.; Xu, D.; Kurhanewicz, J.; Hurd, R.E.; Pauly, J.M.; Nelson, S.J.; et al. Pulse sequence for dynamic volumetric imaging of hyperpolarized metabolic products. J. Magn. Reson. 2008, 193, 139–146.

- Arunachalam, A.; Whitt, D.; Fish, K.; Giaquinto, R.; Piel, J.; Watkins, R.; Hancu, I. Accelerated spectroscopic imaging of hyperpolarized C-13 pyruvate using SENSE parallel imaging. NMR Biomed. 2009, 22, 867–873.

- Chen, H.-Y.; Larson, P.E.; Gordon, J.W.; Bok, R.A.; Ferrone, M.; Van Criekinge, M.; Carvajal, L.; Cao, P.; Pauly, J.M.; Kerr, A.B.; et al. Technique development of 3D dynamic CS-EPSI for hyperpolarized 13 C pyruvate MR molecular imaging of human prostate cancer. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018, 80, 2062–2072.

- Hu, S.; Lustig, M.; Chen, A.P.; Crane, J.; Kerr, A.; Kelley, D.A.; Hurd, R.; Kurhanewicz, J.; Nelson, S.J.; Pauly, J.M.; et al. Compressed sensing for resolution enhancement of hyperpolarized 13C flyback 3D-MRSI. J. Magn. Reson. 2008, 192, 258–264.

- Hu, S.; Lustig, M.; Balakrishnan, A.; Larson, P.E.Z.; Bok, R.; Kurhanewicz, J.; Nelson, S.J.; Goga, A.; Pauly, J.M.; Vigneron, D.B. 3D compressed sensing for highly accelerated hyperpolarized 13 C MRSI with in vivo applications to transgenic mouse models of cancer. Magn. Reson. Med. 2010, 63, 312–321.

- Larson, P.E.Z.; Hu, S.; Lustig, M.; Kerr, A.B.; Nelson, S.J.; Kurhanewicz, J.; Pauly, J.M.; Vigneron, D.B. Fast dynamic 3D MR spectroscopic imaging with compressed sensing and multiband excitation pulses for hyperpolarized 13C studies. Magn. Reson. Med. 2011, 65, 610–619.

- Sigfridsson, A.; Weiss, K.; Wissmann, L.; Busch, J.; Krajewski, M.; Batel, M.; Batsios, G.; Ernst, M.; Kozerke, S. Hybrid multiband excitation multiecho acquisition for hyperpolarized 13 C spectroscopic imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2014, 73, 1713–1717.

- Hu, X.; Levin, D.N.; Lauterbur, P.C.; Spraggins, T. SLIM: Spectral localization by imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 1988, 8, 314–322.

- Von Kienlin, M.; Mejia, R. Spectral localization with optimal pointspread function. J. Magn. Reson. 1991, 94, 268–287.

- Farkash, G.; Markovic, S.; Novakovic, M.; Frydman, L. Enhanced hyperpolarized chemical shift imaging based on a priori segmented information. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019, 81, 3080–3093.

- Zhang, Y.; Gabr, R.E.; Schär, M.; Weiss, R.G.; Bottomley, P.A. Magnetic resonance Spectroscopy with Linear Algebraic Modeling (SLAM) for higher speed and sensitivity. J. Magn. Reson. 2012, 218, 66–76.

- Haldar, J.P.; Liang, Z.-P. Spatiotemporal imaging with partially separable functions: A matrix recovery approach. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 14–17 April 2010; pp. 716–719.

- Lee, H.; Song, J.E.; Shin, J.; Joe, E.; Joo, C.G.; Choi, Y.-S.; Song, H.-T.; Kim, D.-H. High resolution hyperpolarized13C MRSI using SPICE at 9.4 T. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018, 80, 703–710.

- Song, J.E.; Shin, J.; Lee, H.; Choi, Y.; Song, H.; Kim, D. Dynamic hyperpolarized 13 C MR spectroscopic imaging using SPICE in mouse kidney at 9.4 T. NMR Biomed. 2020, 33, e4230.

- Wiesinger, F.; Weidl, E.; Menzel, M.I.; Janich, M.A.; Khegai, O.; Glaser, S.J.; Haase, A.; Schwaiger, M.; Schulte, R.F. IDEAL spiral CSI for dynamic metabolic MR imaging of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate. Magn. Reson. Med. 2012, 68, 8–16.

- Gordon, J.W.; Larson, P.E. Pulse Sequences for Hyperpolarized MRS. Encycl. Magn. Reson. 2016, 5, 1229–1246.

- Gordon, J.W.; Vigneron, D.B.; Larson, P.E.Z. Development of a symmetric echo planar imaging framework for clinical translation of rapid dynamic hyperpolarized 13 C imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2016, 77, 826–832.

- Purvis, L.A.B.; Clarke, W.T.; Biasiolli, L.; Valkovič, L.; Robson, M.D.; Rodgers, C.T. OXSA: An open-source magnetic resonance spectroscopy analysis toolbox in MATLAB. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185356.

- Naressi, A.; Couturier, C.; Devos, J.M.; Janssen, M.; Mangeat, C.; De Beer, R.; Graveron-Demilly, D. Java-based graphical user interface for the MRUI quantitation package. Magma Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2001, 12, 141–152.

- Henry, P.-G.; Öz, G.; Provencher, S.; Gruetter, R. Toward dynamic isotopomer analysis in the rat brainin vivo: Automatic quantitation of13C NMR spectra using LCModel. NMR Biomed. 2003, 16, 400–412.

- Cavassila, S.; Deval, S.; Huegen, C.; Van Ormondt, D.; Graveron-Demilly, D. Cramér-Rao bounds: An evaluation tool for quantitation. NMR Biomed. 2001, 14, 278–283.

- Young, K.; Khetselius, D.; Soher, B.J.; Maudsley, A.A. Confidence images for MR spectroscopic imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2000, 44, 537–545.

- Nelson, S.J.; Brown, T.R. The accuracy of quantification from 1D NMR spectra using the PIQABLE algorithm. J. Magn. Reson. 1989, 84, 95–109.

- Brender, J.R.; Kishimoto, S.; Merkle, H.; Reed, G.; Hurd, R.E.; Chen, A.P.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Munasinghe, J.; Saito, K.; Seki, T.; et al. Dynamic Imaging of Glucose and Lactate Metabolism by 13C-MRS without Hyperpolarization. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3410.

- Harrison, C.; Yang, C.; Jindal, A.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Hooshyar, M.A.; Merritt, M.E.; Sherry, A.D.; Malloy, C.R. Comparison of kinetic models for analysis of pyruvate-to-lactate exchange by hyperpolarized13C NMR. NMR Biomed. 2012, 25, 1286–1294.

- Pagès, G.; Kuchel, P.W. Mathematical Modeling and Data Analysis of Nmr Experiments Using Hyperpolarized 13C Metabolites. Magn. Reson. Insights 2013, 6, MRI.S11084-21.

- Larson, P.E.Z.; Chen, H.; Gordon, J.W.; Korn, N.; Maidens, J.; Arcak, M.; Tang, S.; Criekinge, M.; Carvajal, L.; Mammoli, D.; et al. Investigation of analysis methods for hyperpolarized 13C-pyruvate metabolic MRI in prostate cancer patients. NMR Biomed. 2018, 31, e3997.

- Hill, D.K.; Orton, M.R.; Mariotti, E.; Boult, J.K.R.; Panek, R.; Jafar, M.; Parkes, H.G.; Jamin, Y.; Miniotis, M.F.; Al-Saffar, N.M.S.; et al. Model Free Approach to Kinetic Analysis of Real-Time Hyperpolarized 13C Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71996.

- Daniels, C.J.; McLean, M.A.; Schulte, R.F.; Robb, F.J.; Gill, A.B.; McGlashan, N.; Graves, M.J.; Schwaiger, M.; Lomas, D.J.; Brindle, K.M.; et al. A comparison of quantitative methods for clinical imaging with hyperpolarized 13 C-pyruvate. NMR Biomed. 2016, 29, 387–399.

- Santarelli, M.F.; Positano, V.; Giovannetti, G.; Frijia, F.; Menichetti, L.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.-H.; De Marchi, D.; Lionetti, V.; Aquaro, G.; Lombardi, M.; et al. How the signal-to-noise ratio influences hyperpolarized 13C dynamic MRS data fitting and parameter estimation. NMR Biomed. 2011, 25, 925–934.

- Gallagher, F.A.; Kettunen, M.I.; Brindle, K.M. Imaging pH with hyperpolarized 13 C. NMR Biomed. 2011, 24, 1006–1015.

- Gallagher, F.A.; Kettunen, M.I.; Day, S.E.; Hu, D.-E.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H.; Zandt, R.; Jensen, P.R.; Karlsson, M.; Golman, K.; Lerche, M.H.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of pH in vivo using hyperpolarized 13C-labelled bicarbonate. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 453, 940–943.

- Pourfathi, M.; Kadlecek, S.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Rizi, R.R. Metabolic Imaging and Biological Assessment: Platforms to Evaluate Acute Lung Injury and Inflammation. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11.

- Ishii, M.; Emami, K.; Kadlecek, S.; Petersson, J.S.; Golman, K.; Vahdat, V.; Yu, J.; Cadman, R.V.; MacDuffie-Woodburn, J.; Stephen, M.; et al. Hyperpolarized13C MRI of the pulmonary vasculature and parenchyma. Magn. Reson. Med. 2007, 57, 459–463.

- Lipso, K.W.; Magnusson, P.; Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H. Hyperpolarized 13C MR Angiography. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 22, 90–95.

- Markovic, S.; Fages, A.; Roussel, T.; Hadas, R.; Brandis, A.; Neeman, M.; Frydman, L. Placental physiology monitored by hyperpolarized dynamic 13C magnetic resonance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2429–E2436.

- Madsen, K.E.; Mariager, C.Ø.; Duvald, C.S.; Hansen, E.S.S.; Bertelsen, L.B.; Pedersen, M.; Pedersen, L.H.; Uldbjerg, N.; Laustsen, C. Ex Vivo Human Placenta Perfusion, Metabolic and Functional Imaging for Obstetric Research—A Feasibility Study. Tomography 2019, 5, 333–338.

- Park, J.M.; Josan, S.; Mayer, D.; Hurd, R.E.; Chung, Y.; Bendahan, D.; Spielman, D.M.; Jue, T. Hyperpolarized 13C NMR observation of lactate kinetics in skeletal muscle. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 3308–3318.

- Leftin, A.; Degani, H.; Frydman, L. In vivo magnetic resonance of hyperpolarized [13C1]pyruvate: Metabolic dynamics in stimulated muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2013, 305, E1165–E1171.

- Bastiaansen, J.A.; Cheng, T.; Mishkovsky, M.; Duarte, J.M.; Comment, A.; Gruetter, R. In vivo enzymatic activity of acetylCoA synthetase in skeletal muscle revealed by 13C turnover from hyperpolarized [1-13C]acetate to [1-13C]acetylcarnitine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 4171–4178.

- Laustsen, C. Hyperpolarized 13C Magnetic Resonance Treatment Response Monitoring: A New Paradigm for Multiorgan Metabolic Assessment of Pharmacological Interventions? Diabetes 2016, 65, 3529–3531.

- Lewis, A.J.; Miller, J.J.; McCallum, C.; Rider, O.J.; Neubauer, S.; Heather, L.C.; Tyler, D.J. Assessment of Metformin-Induced Changes in Cardiac and Hepatic Redox State Using Hyperpolarized[1-13C]Pyruvate. Diabetes 2016, 65, 3544–3551.

- Bertelsen, L.B.; Nielsen, P.M.; Qi, H.; Nørlinger, T.S.; Zhang, X.; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H.; Laustsen, C. Diabetes induced renal urea transport alterations assessed with 3D hyperpolarized13C,15N-Urea. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017, 77, 1650–1655.

- Larson, P.E.Z.; Gold, G.E. Science to practice: Can inflammatory arthritis be monitored by using MR imaging with injected hyperpolarized 13C-pyruvate? Radiology 2011, 259, 309–310.

- Neveu, M.-A.; Beziere, N.; Daniels, R.; Bouzin, C.; Comment, A.; Schwenck, J.; Fuchs, K.; Kneilling, M.; Pichler, B.J.; Schmid, A.M. Lactate Production Precedes Inflammatory Cell Recruitment in Arthritic Ankles: An Imaging Study. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2020, 22, 1324–1332.

- Le Page, L.M.; Guglielmetti, C.; Najac, C.F.; Tiret, B.; Chaumeil, M.M. Hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy detects toxin-induced neuroinflammation in mice. NMR Biomed. 2019, 32, e4164.

- Thind, K.; Chen, A.; Friesen-Waldner, L.; Ouriadov, A.; Scholl, T.J.; Fox, M.; Wong, E.; VanDyk, J.; Hope, A.; Santyr, G. Detection of radiation-induced lung injury using hyperpolarized13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2012, 70, 601–609.

- Thind, K.; Jensen, M.D.; Hegarty, E.; Chen, A.P.; Lim, H.; Martínez-Santiesteban, F.; Van Dyk, J.; Wong, E.; Scholl, T.J.; Santyr, G.E. Mapping metabolic changes associated with early Radiation Induced Lung Injury post conformal radiotherapy using hyperpolarized 13C-pyruvate Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging. Radiother. Oncol. 2014, 110, 317–322.

- Lumata, L.L.; Yang, C.; Ragavan, M.; Carpenter, N.R.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Merritt, M.E. Hyperpolarized 13C Magnetic Resonance and Its Use in Metabolic Assessment of Cultured Cells and Perfused Organs. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Volume 561, pp. 73–106.

- Brindle, K.M. Imaging Metabolism with Hyperpolarized13C-Labeled Cell Substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6418–6427.

- Katsikis, S.; Marin-Montesinos, I.; Ludwig, C.; Günther, U.L. Detecting acetylated aminoacids in blood serum using hyperpolarized 13C-1H-2D-NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2019, 305, 175–179.

- Shishmarev, D.; Kuchel, P.W.; Pagès, G.; Wright, A.J.; Hesketh, R.L.; Kreis, F.; Brindle, K.M. Glyoxalase activity in human erythrocytes and mouse lymphoma, liver and brain probed with hyperpolarized 13C-methylglyoxal. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 232.

- Sriram, R.; Sun, J.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.; Mutch, C.; Santos, J.D.L.; Peters, J.; Korenchan, D.E.; Neumann, K.; Van Criekinge, M.; Kurhanewicz, J.; et al. Detection of Bacteria-Specific Metabolism Using Hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyruvate. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 797–805.

- Autry, A.; Park, I.; Kline, C.; Chen, H.-Y.; Gordon, J.; Raber, S.; Hoffman, C.; Kim, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Vigneron, D.; et al. Pilot Study of Hyperpolarized 13C Metabolic Imaging in Pediatric Patients with Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma and Other CNS Cancers. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 178–184.

- Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J.H. Hyperpolarized MR—What’s up Doc? J. Magn. Reson. 2019, 306, 124–127.