Pinus massoniana Lamb. is an important coniferous tree species in ecological environment construction and sustainable forestry development. The function of gene gradual change and coexpression modules of needle and root parts of P. massoniana under continuous drought stress is unclear. The physiological and transcriptional expression profiles of P. massoniana seedlings from 1a half-sibling progeny during drought stress were measured and analyzed. As a result, under continuous drought conditions, needle peroxidase (POD) activity and proline content continued to increase. The malondialdehyde (MDA) content in roots continuously increased, and the root activity continuously decreased. The needles of P. massoniana seedlings may respond to drought mainly through regulating abscisic acid (ABA) and jasmonic acid (JA) hormone-related pathways. Roots may provide plant growth through fatty acid β-oxidative decomposition, and peroxisomes may contribute to the production of ROS, resulting in the upregulation of the antioxidant defense system. P. massoniana roots and needles may implement the same antioxidant mechanism through the glutathione metabolic pathway

- Pinus massoniana

- drought

- coexpression

- hormone

- peroxisome

1. Introduction

Pinus massoniana

Lamb. (Fam.:

Pinus

; Gen.:

Pinus) is widely distributed in China and plays a pivotal role in ecological environment construction and sustainable forestry production. Drought is the most widespread stress factor affecting plant productivity [1]; tree radial growth is mainly limited by dry conditions from May to October, with drought-driven tree mortality [2]. Climate predictions have forecast that hot and dry events will become more frequent in the coming decades [3,4]. Molecular responses to drought stress have been extensively studied in broadleaf species, but studies of needle-leaf species have been limited [5]. Studying the response of needle-leaf plants under drought plays an important role in screening high-quality drought-resistant germplasm resources and revealing the mechanism of drought resistance.

) is widely distributed in China and plays a pivotal role in ecological environment construction and sustainable forestry production. Drought is the most widespread stress factor affecting plant productivity [1]; tree radial growth is mainly limited by dry conditions from May to October, with drought-driven tree mortality [2]. Climate predictions have forecast that hot and dry events will become more frequent in the coming decades [3][4]. Molecular responses to drought stress have been extensively studied in broadleaf species, but studies of needle-leaf species have been limited [5]. Studying the response of needle-leaf plants under drought plays an important role in screening high-quality drought-resistant germplasm resources and revealing the mechanism of drought resistance.

In recent years, the study of drought in

P. massoniana

has focused on the photosynthetic characteristics, plasma membrane structure, osmotic adjustment, endogenous enzyme activity, and endogenous hormone content of seedlings under drought stress; most studies tend to be basic theoretical research [6]. Drought significantly reduces the photosynthetic rate, increment of stem basal diameter and plant height, and biomass accumulation [7].

P. massoniana enhances its drought resistance by altering the ratio of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes: the relative contents of monoterpenes decreases with the intensity of drought stress, and the relative content of sesquiterpenes increases [8,9]. The drought resistance of

enhances its drought resistance by altering the ratio of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes: the relative contents of monoterpenes decreases with the intensity of drought stress, and the relative content of sesquiterpenes increases [8][9]. The drought resistance of

P. massoniana

is controlled by genetic factors; the differences in drought resistance between different families may be related to the genetic differences formed by long-term domestication in different geographical environments [10]. The response to stress is through the regulation of numerous complex and interrelated metabolic networks. The transcriptome is essential for interpreting the functional elements of the genome, revealing the molecular components of tissues and cells and providing an understanding of development [11]. The underground part mainly shows the growth strategy of “increasing” the root system of

P. massoniana

, which grows in an obvious manner. Transcription factors (TFs) play an important role in the adaptation of

P. massoniana needles to drought stress [12,13]. However, there is no research on the continuous gradual change of genes and the role and function of needles and roots under continuous stress conditions. In this study, a high-throughput sequencing method is used to identify the gene expression differences between the needles and roots of a half-sibling progeny of

needles to drought stress [12][13]. However, there is no research on the continuous gradual change of genes and the role and function of needles and roots under continuous stress conditions. In this study, a high-throughput sequencing method is used to identify the gene expression differences between the needles and roots of a half-sibling progeny of

P. massoniana

under continuous drought. This study provides basic data for screening drought resistance factors and understanding drought resistance mechanisms.

2. Physiological and Biochemical Analyses

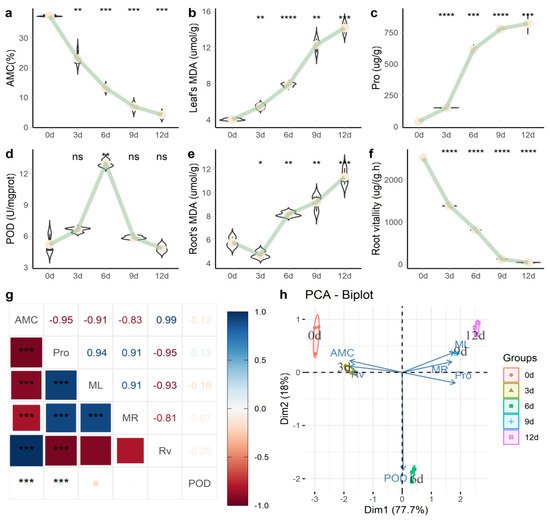

Through physiological measurements of the process of drought stress (

), soil absolute moisture content (AMC) gradually decreased (

a); the plant needles’ malondialdehyde (MDA) (ML) activity (

b) and the content of needle proline (Pro) (

c) also continued to rise. Needle peroxidase (POD) activity (

d) reached its peak in 6 d, after which the needle content continued to decline. Root MDA (MR) activity (

e) and root activity (RV) (

f) continued to increase over time. Pro and ML showed a significant positive correlation (

= 0.94), while RV and Pro showed a significant negative correlation (

= −0.95) (

g). Principal component analysis (PCA) analysis (

h) found that the difference between the 6-d group and other groups was mainly reflected in POD activity.

Physiological changes of

under persistent drought stress. (

) Absolute water content in soil (AMC); (

) malondialdehyde (MDA) content in needles; (

) needle proline (Pro) content; (

) needle peroxidase (POD) activity; (

) MDA content in roots; (

) root activity; (

) correlation analysis of various biochemical indicators; (

) PCA analysis. Note: In

a–f, we used the “0 d” group as a reference to compare the mean and added

-value and significance markers (“*” indicates that there is a difference compared with the “0 d” group; *

< 0.05, **

< 0.01, ***

< 0.001, ****

≤ 0.0001 and “ns” means no difference). In

g, the number represents the magnitude of the correlation, and the color represents the positive and negative correlations.

3. Weighted Gene Coexpression Network Analysis (WGCNA) Analysis

4. Discussion

Large-scaleBy biogeographical shifts in forest tree distributions are predicted in response to altered precipitation and temperature regimes associated with climate change [15]. Senalyzing the need sources with higher plasticity perform better in core habitat conditions [16].e and Paying attention to the response of forest species to drought will help us use molecular markers and field experiments to screen for drought-resistant core germplasm resources, which are necessary to improve forest productivity under the conditions of climate change. Transcription differences between different tissue parts/organs are essential for a comprehensive understanding of the stress response of the entire plant. By measuring the physiological indexes of needles and roots during drought of the half-sibling progeny ofoot coexpression module of P. massoniana, the gene expression profiles during the drought process were constructed. This study provides further insights into the process of drought response and tolerance in P. massoniana.

In re, the coexpressed gene sponse to increased H2O2 levels due tt co stress, plants have evolved different enzymatic and nonenzymatic mechanisms, including free radical scavengers such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase, as well as ascorbic acid-glutathione circulating enzymes [17,18]. Durlection was determined, and the analysings drought, total NSC (TNSC, soluble sugars plus starch) values decrease, particularly in leaves of P. sylvestris L. [19]. MDA and Prevealed severo, SOD activity, root shoot ratio, and root mass ratio increased significantly during drought treatment in P. massoniana [20]. Under drought conditions, MDA in needles (Figure 1l main sub) and the content of proline continued to rise (Figure 1c), the MDA in rootxpress (Figure 1e) continued to rise, and root vitality (Figure 1n prof) continued to decline.

Ales a sun planwit, P. massoniana ha s higher light compensation and saturation points and a stronger ability to adapt to strong light. Under moderate (field-water-holding capacity 35%–45%) and severe (20%–30%) drought stress, net photosynthetic rate and transpiration rate decreased significantly [21]. Thimilar expressions, called reduction of photosynthesis and chlorophyll contents under drought stress is the most direct manifestationcoexpression modules of[14]. plants undWer drought stress. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that plant hormone signal transduction (ko04075) was always enriched in the different teams of needles (Figure S3). STEM analys generated a consensus network to is found that photosynthesis (ko00195), photosynthesis-antenna proteins (ko00196), porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism (ko00860), and other metabolic pathways were enriched in the needle Profile9 entify conserved module (Figure 4a.1). The modules’ inner genes showed the expression trend 0, −1, −2, −3, −4. ADH1, as one of the marker genes for drought or ABA response, is induced by high ABA levels in Arabidopsis undthat are needle ser drought stress [22,23]. Overex-spression of AtADH1 cifincreases the transcription levels of multiple stress-related genes and the accumulation of soluble sugars and callose deposition and enhances the abiotic and biological stress resistance of and root set-specific in ArP. mabidopsiss [24]. During drought stress induced by PEG in Arabidopsnis thaliana, ADH1 and.

A two other ADH genestal of responded11 to drought in needles and roots together [25]. Umodules (24 to 1208 gender drought stress, 24 ADH1 s) were upridegulatntified in the needle Profile41 module, and 12 ADH1 werea upregulated in the needle Profile41otal of 14 module. In cell signaling, protein kinases (PKs) and phosphatases (PPs) are key enzymes in the regulation mechanism of protein reversible phosphorylation [26]. Plans (37 to 932 genes) were identified in the PP2Cs participate in various signal cascades, such as ABA and sroot module (Figure 2alicylic acid (SA)–ABA crosstalk [27]. OPR is iInvolved in the biosynthesis of JA. The key process in the synthetic pathway is the conversion of cis-12-oxo-docosadienoic acid (OPDA) to 12-oxo-phytoenoic acid (OPC-8:0), catalyzed by OPR; the reaction takes place on the peroxisomes [28,29,30]. The function of OPR m the needle module, the genes of the black and may be conserved in higher plants, and rice OsOPR7 can make enta sup for the phenotype of Arabidopsis opr3 bmutants [31]. In the Profile41 module in needles (Figure 4a.2), 8 ADH1, 6 OPRs, and PP2C in ts she ABA pathoway, MYC2 in the JA pathway, and other related genes were enriched, indicating that the needles of P. massoniana may mainly ed a downward tregulate ABA and JA-hormone-synthesis-related pathways in response to with drought.

The major ROS regulatory enzyme systems in plant peroxisomes include catalase, all ascorbic acid-glutathione cycle components, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) [32]. Peroxisomes conime. GO enrichment showed thatribute to several metabolic processes, such as β-oxidation of fatty acids,flavonoid biosynthesis of ether phospholipids, and (GO: 0009813), the flavonoid metabolism of ROS. β-oxidation of fatty acids and detoxification of ROS are generally accepted as being fundamental functions of peroxisomes [33,34]. β-oxidation conprocess (GO: 0009812), and other biological processiests of four enzymatic steps: ACX oxidation, MFP2 hydration and dehydration, and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (KAT) thiolysis. β-oxidation degrades fatty acids only in the peroxisomes in plants and their derivatives [35]. Peroxisomal ab were enriched in the megenta sundance can be used as a cellular sensor for drought and heat stress responses; severe drought stress induces peroxisomal proliferation and affects the size of the peroxisomes [36,37]. GOLS imodule. The genes of the turquoise s a key rate-ubmodulimiting enzyme for raffinose synthesis [38]. Ove in neerexprdlession of AtGOLS2 in rice significantly imprhoved the drought tolerance of transgenic rice; at the same time, the yield of transgenic rice lines under drought conditions was significantly higher than that of the control [39]. In the rwed an increasing trend with proloot Profie41 module (Figure 4b.2), ko00071, ko00592, and ko01212 pathways wgere enriched, and genes such as MFP2, ADH1, ADH7A1, and ACOX wed dre enriched. In the ko00052 pathway, genes such as GOLS were enriched, and related differential genes presented gene expression trends of ught time (0,1,2,3,4Figure 2b). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis found that phenyglpropanoid biosynthesis (ko00940) was enriched in the root Profile9 module (Figure 4utathione metab.1); most (25/31) of the genes belong to peroxidase (K00430). β-oxidation is believed to enhance the production of stress-induced ROS, which adversely affects plant survival under adverse environmental conditions [40]. Under droulism (ko00480), MAPK signalinght stress, plants tend to increase ROS levels, which, in turn, leads to an upregulation of the antioxidant defense system [41]. This shows that the declining pathway-peroxidase-related genes may act as inhibitor agents, but the related regulatory mechanisms are currently unclear. On the other hand, fatty acids are catabolized by β-oxidation to acetyl-CoA, producing sugar, glyoxylic acid, and sugar for seedling growth and development without photosynthesis xenobiosis [42]. This shows thnt (ko04016), flavonoid biosynthesis (ko00941), at under continuous drought conditions of P. massoniana, th othe roots may provide plant growth through fatty acid β-oxidative decomposition, and P. massoniana p pathways weroxisomes may contribute to the production of ROS, resulting in the upregulation of the antioxidant defense system.

P. pinaster root enriched. In the root module, stem, mature, and aerial organs, under nontarget metabolomics analysis, were found to have a large number of flavonoids, detected in aerial organs, mainly in root glutathione pathway induction. It is believed that aerial organs and roots activate different antioxidant mechanisms [43]. Transcriptomhe turquoise submodule and the nee clustering analysis of P. halepensis found that ROS were cleared by an ascorbic acid–glutathione cycle, fatty acid and cell wall biosynthesis, stomatal activity, and biosynthesis of flavonoids and terpenoids [5]. The droe submodught-tolerant seed sources of P. halepensis s showed incareased levels of glutathione, methionine, and cysteine [44]. Thed the most ge P. massoniana glutathione peroxidase gene, PmGPX6,, is highly exupressed in the roots. Overexpression of PmGPX6 in A to 762. GO enrabidopsis and wild-type plants have little difference in phenotype and root length under normal water conditions, but under drought stress, in transgenic plants, the root system is longer [45]. Pchment of these 762 genes showed that phospholipid –hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase, peroxidase, and other a activities are related to reducing the accumulation of reactive oxygen in stress-induced environments [46]. The coexpression module of phospholipid–hydroperoxidey, glutathione peroxidase activity, (glutathione peroxidase activity), and other molecular functions in the roots and needles of were enriched.

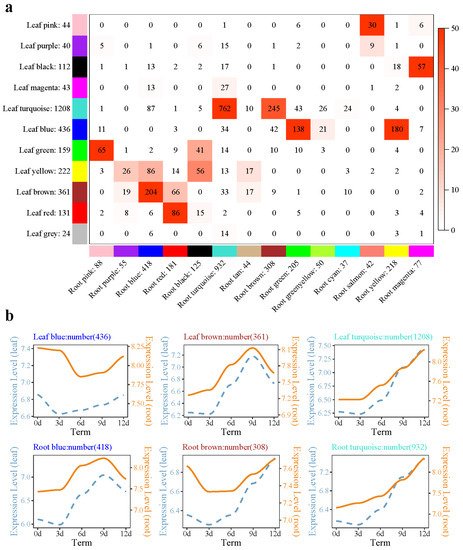

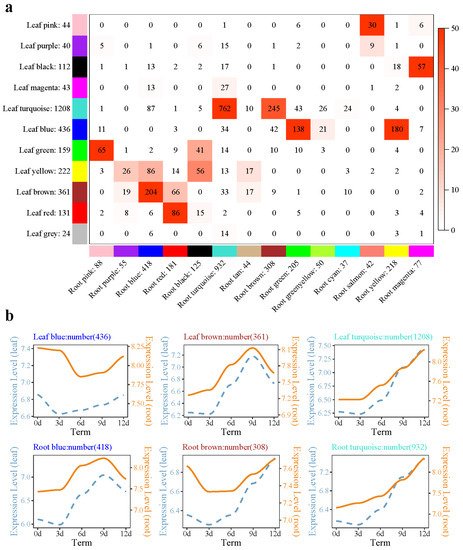

Figure 2. Root and needle coexpression network analysis of the P. massoniana drought process. (a) Overlap between needle set-specific and root set-specific modules in P. massoniana; (b) different module gene expression patterns in needles and roots. Note: In subfigure (a), each row in the table corresponds to one needle set-specific module, and each column corresponds to one root set-specific module. The number in the labeled heatmap indicates the genes counted in the intersection between two parts of P. massoniana. Coloring of the table indicates significant overlap, evaluated using Fisher’s exact test. In subfigure (b), the left side of the double-axis represents the needles, the right side represents the roots, the text includes the number of modules and module names, and the gene trends in the module are processed by taking the logarithm of the gene expression in the module, fitted in a linear simulation.

4. Discussion

Large-scale biogeographical shifts in forest tree distributions are predicted in response to altered precipitation and temperature regimes associated with climate change [15]. Seed sources with higher plasticity perform better in core habitat conditions [16]. Paying attention to the response of forest species to drought will help us use molecular markers and field experiments to screen for drought-resistant core germplasm resources, which are necessary to improve forest productivity under the conditions of climate change. Transcription differences between different tissue parts/organs are essential for a comprehensive understanding of the stress response of the entire plant. By measuring the physiological indexes of needles and roots during drought of the half-sibling progeny of P. massoniana, the gene expression profiles during the drought process were constructed. This study provides further insights into the process of drought response and tolerance in P. massoniana.

In response to increased H2O2 levels due to stress, plants have evolved different enzymatic and nonenzymatic mechanisms, including free radical scavengers such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase, as well as ascorbic acid-glutathione circulating enzymes [17][18]. During drought, total NSC (TNSC, soluble sugars plus starch) values decrease, particularly in leaves of P. sylvestris L. [19]. MDA and Pro, SOD activity, root shoot ratio, and root mass ratio increased significantly during drought treatment in P. massoniana [20]. Under drought conditions, MDA in needles (Figure 1b) and the content of proline continued to rise (Figure 1c), the MDA in roots (Figure 1e) continued to rise, and root vitality (Figure 1f) continued to decline.

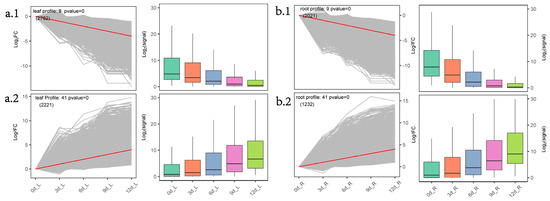

As a sun plant, P. massoniana has higher light compensation and saturation points and a stronger ability to adapt to strong light. Under moderate (field-water-holding capacity 35%–45%) and severe (20%–30%) drought stress, net photosynthetic rate and transpiration rate decreased significantly [21]. The reduction of photosynthesis and chlorophyll contents under drought stress is the most direct manifestation of plants under drought stress. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that plant hormone signal transduction (ko04075) was always enriched in the different teams of needles. STEM analysis found that photosynthesis (ko00195), photosynthesis-antenna proteins (ko00196), porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism (ko00860), and other metabolic pathways were enriched in the needle Profile9 module (Figure 3a.1). The modules’ inner genes showed the expression trend 0, −1, −2, −3, −4. ADH1, as one of the marker genes for drought or ABA response, is induced by high ABA levels in Arabidopsis under drought stress [22][23]. Overexpression of AtADH1 increases the transcription levels of multiple stress-related genes and the accumulation of soluble sugars and callose deposition and enhances the abiotic and biological stress resistance of Arabidopsis [24]. During drought stress induced by PEG in Arabidopsis thaliana, ADH1 and two other ADH genes responded to drought in needles and roots together [25]. Under drought stress, 24 ADH1 were upregulated in the needle Profile41 module, and 12 ADH1 were upregulated in the needle Profile41 module. In cell signaling, protein kinases (PKs) and phosphatases (PPs) are key enzymes in the regulation mechanism of protein reversible phosphorylation [26]. Plant PP2Cs participate in various signal cascades, such as ABA and salicylic acid (SA)–ABA crosstalk [27]. OPR is involved in the biosynthesis of JA. The key process in the synthetic pathway is the conversion of cis-12-oxo-docosadienoic acid (OPDA) to 12-oxo-phytoenoic acid (OPC-8:0), catalyzed by OPR; the reaction takes place on the peroxisomes [28][29][30]. The function of OPR may be conserved in higher plants, and rice OsOPR7 can make up for the phenotype of Arabidopsis opr3 mutants [31]. In the Profile41 module in needles (Figure 3a.2), 8 ADH1, 6 OPRs, and PP2C in the ABA pathway, MYC2 in the JA pathway, and other related genes were enriched, indicating that the needles of P. massoniana may mainly regulate ABA and JA-hormone-synthesis-related pathways in response to drought.

Figure 4. Cluster analysis of gene expression trends during drought stress in P. massoniana. (a.1) and (a.2): Two STEM significance modules (needle Profile9 and needle Profile41) of the needles during drought stress; (b.1) and (b.2): Two short time-series expression miner (STEM) significance modules (root Profile9 and root Profile41) of the roots during drought stress. Note: We used STEM software to perform trend clustering analysis and divided the trends into 5 stages according to the time before and after input and normalized the union of all the combined DEGs from the five stages. The left side of each subfigure is the significant module selected in the STEM analysis; the right side is the box plot of the corresponding gene expression after taking the logarithm.

The major ROS regulatory enzyme systems in plant peroxisomes include catalase, all ascorbic acid-glutathione cycle components, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) [32]. Peroxisomes contribute to several metabolic processes, such as β-oxidation of fatty acids, biosynthesis of ether phospholipids, and metabolism of ROS. β-oxidation of fatty acids and detoxification of ROS are generally accepted as being fundamental functions of peroxisomes [33][34]. β-oxidation consists of four enzymatic steps: ACX oxidation, MFP2 hydration and dehydration, and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (KAT) thiolysis. β-oxidation degrades fatty acids only in the peroxisomes in plants and their derivatives [35]. Peroxisomal abundance can be used as a cellular sensor for drought and heat stress responses; severe drought stress induces peroxisomal proliferation and affects the size of the peroxisomes [36][37]. GOLS is a key rate-limiting enzyme for raffinose synthesis [38]. Overexpression of AtGOLS2 in rice significantly improved the drought tolerance of transgenic rice; at the same time, the yield of transgenic rice lines under drought conditions was significantly higher than that of the control [39]. In the root Profie41 module (Figure 3b.2), ko00071, ko00592, and ko01212 pathways were enriched, and genes such as MFP2, ADH1, ADH7A1, and ACOX were enriched. In the ko00052 pathway, genes such as GOLS were enriched, and related differential genes presented gene expression trends of (0,1,2,3,4). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis found that phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (ko00940) was enriched in the root Profile9 module (Figure 3b.1); most (25/31) of the genes belong to peroxidase (K00430). β-oxidation is believed to enhance the production of stress-induced ROS, which adversely affects plant survival under adverse environmental conditions [40]. Under drought stress, plants tend to increase ROS levels, which, in turn, leads to an upregulation of the antioxidant defense system [41]. This shows that the declining peroxidase-related genes may act as inhibitor agents, but the related regulatory mechanisms are currently unclear. On the other hand, fatty acids are catabolized by β-oxidation to acetyl-CoA, producing sugar, glyoxylic acid, and sugar for seedling growth and development without photosynthesis xenobiosis [42]. This shows that under continuous drought conditions of P. massoniana, the roots may provide plant growth through fatty acid β-oxidative decomposition, and P. massoniana peroxisomes may contribute to the production of ROS, resulting in the upregulation of the antioxidant defense system.

P. pinaster root, stem, mature, and aerial organs, under nontarget metabolomics analysis, were found to have a large number of flavonoids, detected in aerial organs, mainly in root glutathione pathway induction. It is believed that aerial organs and roots activate different antioxidant mechanisms [43]. Transcriptome clustering analysis of P. halepensis found that ROS were cleared by an ascorbic acid–glutathione cycle, fatty acid and cell wall biosynthesis, stomatal activity, and biosynthesis of flavonoids and terpenoids [5]. The drought-tolerant seed sources of P. halepensis showed increased levels of glutathione, methionine, and cysteine [44]. The P. massoniana glutathione peroxidase gene, PmGPX6, is highly expressed in the roots. Overexpression of PmGPX6 in Arabidopsis and wild-type plants have little difference in phenotype and root length under normal water conditions, but under drought stress, in transgenic plants, the root system is longer [45]. Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase, peroxidase, and other activities are related to reducing the accumulation of reactive oxygen in stress-induced environments [46]. The coexpression module of phospholipid–hydroperoxideglutathione peroxidase activity, glutathione peroxidase activity, and other molecular functions in the roots and needles of

P. massoniana

were enriched. It shows that the glutathione metabolic pathway between the roots and needles of

P. massoniana

may implement the same mechanism of activating antioxidants.

References

- Hu, L.; Xie, Y.; Fan, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Li, H.; Song, J.; Kong, L. Comparative analysis of root transcriptome profiles between drought-tolerant and susceptible wheat genotypes in response to water stress. Plant Sci. 2018, 272, 276–293.

- Li, Y.; Dong, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, F.; Cao, X.; Fang, K. Growth decline of Pinus Massoniana in response to warming induced drought and increasing intrinsic water use efficiency in humid subtropical China. Dendrochronologia 2019, 57, 125609.

- Stocker, T. (Ed.) Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014.

- Sun, M.; Huang, D.; Zhang, A.; Khan, I.; Yan, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L. Transcriptome analysis of heat stress and drought stress in pearl millet based on Pacbio full-length transcriptome sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 323.

- Fox, H.; Doron-Faigenboim, A.; Kelly, G.; Bourstein, R.; Attia, Z.; Zhou, J.; Moshe, Y.; Moshelion, M.; David-Schwartz, R. Transcriptome analysis of Pinus halepensis under drought stress and during recovery. Tree Physiol. 2018, 38, 423–441.

- Tan, J.; Tang, S.S.; Chen, H. Advances of Drought Resistance in Pinus massoniana. Guangxi For. Sci. 2017, 46, 1–7.

- Deng, X.; Xiao, W.; Shi, Z.; Zeng, L.; Lei, L. Combined Effects of Drought and Shading on Growth and Non-Structural Carbohydrates in Pinus massoniana Lamb. Seedlings. Forests 2020, 11, 18.

- Quan, W.; Ding, G. Root tip structure and volatile organic compound responses to drought stress in Masson pine (Pinus massoniana Lamb.). Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 258.

- Quan, W.; Ding, G. Dynamic of volatiles and endogenous hormones in pinus massoniana needles under drought stress. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2017, 53, 49–55.

- Du, M.; Ding, G.; Zhao, X. Responses to continuous drought stress and drought resistance of different masson pine families. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2017, 53, 21–29.

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63.

- Du, M. The Molecular Mechanism of Masson Pine Drought-Resistant Germplasm in Response to Drought Stress. Guizhou University, 2018. Available online: (accessed on 1 March 2021). (In Chinese).

- Du, M.; Ding, G.; Cai, Q. The Transcriptomic Responses of Pinus massoniana to Drought Stress. Forests 2018, 9, 326.

- Garg, R.; Singh, V.K.; Rajkumar, M.S.; Kumar, V.; Jain, M. Global transcriptome and coexpression network analyses reveal cultivar-specific molecular signatures associated with seed development and seed size/weight determination in chickpea. Plant J. 2017, 91, 1088–1107.

- Taïbi, K.; Del Campo, A.D.; Mulet, J.M.; Flors, J.; Aguado, A.; Del Campo, A. Testing Aleppo pine seed sources response to climate change by using trial sites reflecting future conditions. New For. 2014, 45, 603–624.

- Taïbi, K.; Del Campo, A.D.; Aguado, A.; Mulet, J.M. The effect of genotype by environment interaction, phenotypic plasticity and adaptation on Pinus halepensis reforestation establishment under expected climate drifts. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 84, 218–228.

- Noctor, G.; Foyer, C.H. ASCORBATE AND GLUTATHIONE: Keeping Active Oxygen Under Control. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1998, 49, 249–279.

- Miao, Y.; Lv, D.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.-C.; Chen, J.; Song, C.-P. An Arabidopsis Glutathione Peroxidase Functions as Both a Redox Transducer and a Scavenger in Abscisic Acid and Drought Stress Responses. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 2749–2766.

- Aguadé, D.; Poyatos, R.; Gómez, M.; Oliva, J.; Martinez-Vilalta, J. The role of defoliation and root rot pathogen infection in driving the mode of drought-related physiological decline in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). Tree Physiol. 2015, 35, 229–242.

- Wang, D.; Huang, G.; Duan, H.; Lei, X.; Liu, W.; Wu, J.; Fan, H. Effects of drought and nitrogen addition on growth and leaf physiology of pinus massoniana seedlings. Pak. J. Bot. 2019, 51, 1575–1585.

- Zhang, X. Photosynthetic Physiology for Pinus massoniana in Jin Yun Mountain; Beijing Forestry University: Beijing, China, 2013; p. 48. Available online: (accessed on 1 March 2021). (In Chinese)

- Abe, H.; Urao, T.; Ito, T.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) Function as Transcriptional Activators in Abscisic Acid Signaling. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 63–78.

- Butt, H.I.; Yang, Z.; Gong, Q.; Chen, E.; Wang, X.; Zhao, G.; Ge, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, F. GaMYB85, an R2R3 MYB gene, in transgenic Arabidopsis plays an important role in drought tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 142.

- Shi, H.; Liu, W.; Yao, Y.; Wei, Y.; Chan, Z. Alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (ADH1) confers both abiotic and biotic stress resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2017, 262, 24–31.

- Myint, T.; Ismawanto, S.; Namasivayam, P.; Napis, S.; Abdulla, M.P. Expression analysis of the ADH genes in Arabidopsis plants exposed to PEG-induced water stress. World J. Agric. Res. 2015, 3, 57–65.

- Luan, S. Protein phosphatases and signaling cascades in higher plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1998, 3, 271–275.

- Manohar, M.; Wang, D.; Manosalva, P.M.; Choi, H.W.; Kombrink, E.; Klessig, D.F. Members of the abscisic acid co-receptor PP2C protein family mediate salicylic acid-abscisic acid crosstalk. Plant Direct 2017, 1, e00020.

- Schaller, F.; Biesgen, C.; Mufcssig, C.; Altmann, T.; Weiler, E.W. 12-Oxophytodienoate reductase 3 (OPR3) is the isoenzyme involved in jasmonate biosynthesis. Planta 2000, 210, 979–984.

- Turner, J.G.; Ellis, C.; Devoto, A. The Jasmonate Signal Pathway. Plant Cell 2002, 14 (Suppl. 1), S153–S164.

- Strassner, J.; Schaller, F.; Frick, U.B.; Howe, G.A.; Weiler, E.W.; Amrhein, N.; Schaller, A. Characterization and cDNA-microarray expression analysis of 12-oxophytodienoate reductases reveals differential roles for octadecanoid biosynthesis in the local versus the systemic wound response. Plant J. 2002, 32, 585–601.

- Tani, T.; Sobajima, H.; Okada, K.; Chujo, T.; Arimura, S.-I.; Tsutsumi, N.; Nishimura, M.; Seto, H.; Nojiri, H.; Yamane, H. Identification of the OsOPR7 gene encoding 12-oxophytodienoate reductase involved in the biosynthesis of jasmonic acid in rice. Planta 2008, 227, 517–526.

- Corpas, F.J.; Barroso, J.B.; Palma, J.M.; Rodriguez-Ruiz, M. Plant peroxisomes: A nitro-oxidative cocktail. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 535–542.

- Islinger, M.; Grille, S.; Fahimi, H.D.; Schrader, M. The peroxisome: An update on mysteries. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 137, 547–574.

- Bolte, K.; Rensing, S.A.; Maier, U.G. The evolution of eukaryotic cells from the perspective of peroxisomes: Phylogenetic analyses of peroxisomal beta-oxidation enzymes support mitochondria-first models of eukaryotic cell evolution. BioEssays 2015, 37, 195–203.

- Pan, R.; Liu, J.; Hu, J. Peroxisomes in plant reproduction and seed-related development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 61, 784–802.

- Hinojosa, L.; Sanad, M.N.; Jarvis, D.E.; Steel, P.; Murphy, K.; Smertenko, A. Impact of heat and drought stress on peroxisome proliferation in quinoa. Plant J. 2019, 99, 1144–1158.

- Sanad, M.N.M.E.; Smertenko, A.; Garland-Campbell, K.A. Differential Dynamic Changes of Reduced Trait Model for Analyzing the Plastic Response to Drought Phases: A Case Study in Spring Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 504.

- Saravitz, D.M.; Pharr, D.M.; Carter, T.E. Galactinol Synthase Activity and Soluble Sugars in Developing Seeds of Four Soybean Genotypes. Plant Physiol. 1987, 83, 185–189.

- Selvaraj, M.G.; Ishizaki, T.; Valencia, M.; Ogawa, S.; Dedicova, B.; Ogata, T.; Yoshiwara, K.; Maruyama, K.; Kusano, M.; Saito, K.; et al. Overexpression of an Arabidopsis thaliana galactinol synthase gene improves drought tolerance in transgenic rice and increased grain yield in the field. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 1465–1477.

- Yu, L.; Fan, J.; Xu, C. Peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation negatively impacts plant survival under salt stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2019, 14, 1–3.

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, J. Water stress-induced abscisic acid accumulation triggers the increased generation of reactive oxygen species and up-regulates the activities of antioxidant enzymes in maize leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 2401–2410.

- Nakagawa, A.C.S.; Itoyama, H.; Ariyoshi, Y.; Ario, N.; Tomita, Y.; Kondo, Y.; Iwaya-Inoue, M.; Ishibashi, Y. Drought stress during soybean seed filling affects storage compounds through regulation of lipid and protein metabolism. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018, 40, 111.

- De Miguel, M.; Guevara, M.Á.; Sánchez-Gómez, D.; de María, N.; Díaz, L.M.; Mancha, J.A.; de Simón, B.F.; Cadahía, E.; Desai, N.; Aranda, I.; et al. Organ-specific metabolic responses to drought in Pinus pinaster Ait. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 102, 17–26.

- Taïbi, K.; Del Campo, A.D.; Vilagrosa, A.; Bellés, J.M.; López-Gresa, M.P.; Pla, D.; Calvete, J.J.; López-Nicolás, J.M.; Mulet, J.M. Drought Tolerance in Pinus halepensis Seed Sources As Identified by Distinctive Physiological and Molecular Markers. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1202.

- Cai, Q.; Ding, G.J.; Wen, X.P. Cloning of Glutathione Peroxidase Pm GPX6 Gene from Pinus massoniana and the Study on Drought Tolerance of Transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. For. Res. 2016, 29, 839–846.

- Baozhang, B.; Jinzhi, J.; Liping, H.; Song, B. Improvement of TTC method determining root activity in corn. Maize Sci. 1994, 2, 44–47.