Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) causes severe pulmonary diseases, leading to high morbidity and mortality. It has been reported that inflammasomes such as NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) play an important role in the host defense against S. pneumoniae infection. However, the role of NLRP6 in vivo and in vitro against S. pneumoniae remains unclear. Therefore, we investigated the role of NLRP6 in regulating the S. pneumoniae-induced inflammatory signaling pathway in vitro and the role of NLRP6 in the host defense against S. pneumoniae in vivo by using NLRP6−/− mice.

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- NLRP6

- inflammasome

- IL-1β

- inflammatory response

1. Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) is a Gram-positive extracellular bacteria causing severe infection in the respiratory tract, leading to high morbidity and mortality worldwide, especially among children. It has been reported that S. pneumoniae causes at least 1.2 million infant deaths every year worldwide [1]. S. pneumoniae is an opportunistic bacterial pathogen and causes invasive pneumococcal diseases such as community-acquired pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, and otitis media [2]. S. pneumoniae often colonizes on the mucosal surface of the upper respiratory tract and the dynamic process makes this pathogen invade the lower airways [3][4]. The host in turn produces a series of immune responses including inflammatory response against S. pneumoniae infection [5][6]. Therefore, understanding the host response to S. pneumoniae is essential to prevent and treat S. pneumoniae infection.

The innate immunity plays an important role in the host defense against pathogens in the early stage of infection. The innate immune response is regulated by different pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in the immune cells, such as toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) [7]. Inflammasome is a member of NLRs family and has been recognized for its critical role in innate immunity against microbial infection [8][9]. To date, multiple proteins receptors have been confirmed to assemble inflammasomes, such as the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD), leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-containing protein (NLR) family members NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRP6, NLRP7, NLRC4, and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) etc. NLRP3 is one of the most extensively studied inflammasomes [7][10][11]. Caspase-1 is activated in canonical inflammasomes, while related caspase-11 is activated in the non-canonical pathway via sensing of cytoplasmic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria. However, the results of canonical and non-canonical inflammasome activation are similar [12]. Caspase-1 induces the processing and release of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL) 1β and IL-18, as well as a lytic form of cell death called pyroptosis. Caspase-11 directly promotes the cleavage of gasdermin D (GSDMD), which triggers a secondary activation of canonical NLRP3 inflammasome for cytokine release [13]. It has been reported that S. pneumoniae induced activation of NLRP3 and AIM2 in macrophages results in the maturation and secretion of IL-1β [14][15]. Our previous studies have shown that the absence of NLRP3 or AIM2 significantly reduced the host defense against S. pneumoniae, resulting in higher mortality and bacterial colonization in the lungs, which indicates the protective role of NLRP3 and AIM2 in the host against S. pneumoniae infection [12][16][17]. However, among these inflammasomes studies, the role of NLRP6 in the host is less studied.

NLRP6 has been identified to play an important role in the intestinal homeostasis [18]. For example, NLRP6 has a positive role in the intestine against Citrobacter rodentium infection by regulating goblet cell mucus secretion [19]. In contrast, NLRP6 also has been found to negatively regulate host defense against Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella [20][21][22]. These results demonstrate that NLRP6 plays a complicated role in the host in response to different pathogens. However, it is still unclear what the role of NLRP6 is in the host against S. pneumoniae.

2. NLRP6 Inflammasome Mediates Proinflammatory Cytokines Secretion during Macrophages Infection with S. pneumoniae

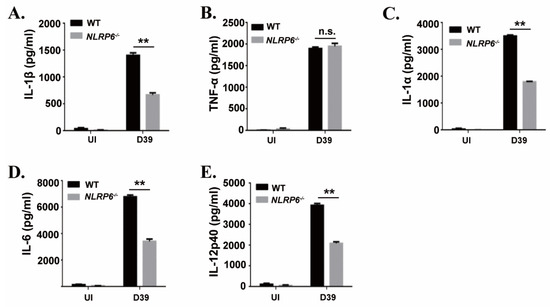

To investigate the effect of the NLRP6 inflammasome on the production of proinflammatory cytokines during macrophages infection with S. pneumoniae, mouse primary macrophages from C57BL/6 (WT) and NLRP6−/− were infected with S. pneumoniae. After 24 h of infection, inflammatory cytokines secretion in the supernatants were determined by ELISA. The results showed that S. pneumoniae induced a high level of secretion of IL-1β, IL-1α, IL-6, and IL-12p40 in WT mice macrophages, while these cytokines’ secretion was significantly reduced in NLRP6−/− macrophages (Figure 1). However, there was no difference in the production of TNF-α. These results indicate that the production of IL-1β, IL-1α, IL-6, and IL-12p40 is partially dependent on the activation of NLRP6 in S. pneumoniae-infected macrophages.

Figure 1. NLR family pyrin domain containing 6 (NLRP6) mediates inflammatory cytokines expression in S. pneumoniae-infected macrophages. Macrophages from WT or NLRP6−/− mice were uninfected or infected with S. pneumoniae at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 for 6 h. Then, gentamicin (100 μg/mL) was added to the cultures and incubated for 18 h. After 24 h infection, the supernatants were collected and the levels of IL-1β (A), TNF-α (B), IL-1α (C), IL-6 (D) and IL-12p40 (E) in the supernatants were determined by ELISA. All of the experiments were independently performed three times. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test (** p < 0.01).

3. NLRP6 Is Involved in the Maturation and Secretion of IL-1β But Not in the Induction of IL-1β Transcription in S. pneumoniae-Infected Macrophages

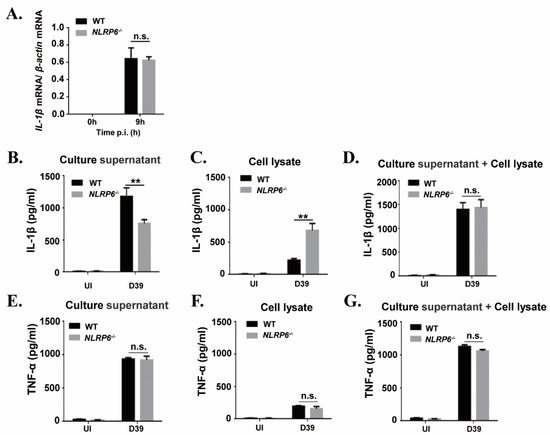

It has been known that IL-1β is synthesized as a 31 kDa precursor protein (pro-IL-1β) and then processed into a 17 kDa mature form protein for secretion. To explore the mechanism of NLRP6-mediated IL-1β secretion during macrophages infected with S. pneumoniae, we examined S. pneumoniae-induced expression of IL-1β mRNA and IL-1β protein in the supernatants and cell lysates in WT and NLRP6−/− macrophages. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) results showed that the expression of IL-1β mRNA was significantly induced in S. pneumoniae-infected macrophages of WT and NLRP6−/− mice at 9 h post infection (Figure 2A), indicating that NLRP6 did not affect S. pneumoniae-induced IL-1β transcription. However, the protein level of IL-1β in the supernatants was significantly lower in S. pneumoniae-infected NLRP6−/− macrophages compared with WT macrophages, but IL-1β production was significantly higher in cell lysates (Figure 2B,C). In contrast to IL-1β, S. pneumoniae-induced TNF-α production was not affected in NLRP6−/− macrophages (Figure 2E–G). Notably, the total level of IL-1β production in the supernatants and cell lysates was almost the same in S. pneumoniae-infected WT and NLRP6−/− macrophages (Figure 2D), indicating that the protein production of IL-1β was consistent with the pattern of mRNA expression. Thus, these data indicated that NLRP6 regulates the maturation and secretion of IL-1β but does not regulate the induction of IL-1β transcription in S. pneumoniae-infected macrophages.

Figure 2. NLRP6 mediates maturation and secretion of IL-1β but does not regulate the induction of IL-1β mRNA in S. pneumoniae-infected macrophages. Macrophages were infected with the S. pneumoniae at an MOI of 1. (A) Total cellular RNA was extracted 9 h after infection, and the level of IL-1β mRNA expression was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. The levels of IL-1β (B–D) and TNF-α (E–G) in the culture supernatants and cell lysates were determined by ELISA at 24 h post infection. All of the experiments independently performed three times. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test (** p < 0.01).

4. Discussion

S. pneumoniae is an important pathogen causing lung diseases, leading to high morbidity and mortality in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals. Thus far, treatment of bacterial pneumonia mainly relies on antibiotics, but the increase of antibiotic resistant bacterial strains makes the treatment less effective. Understanding the host innate immune response will contribute to the development of alternative therapeutic approaches. Inflammasomes are complex proteins and have been characterized by a critical role in clearance of invading bacteria in the host. NLRP6 is a newly and specially characterized member of the NLRs family, which prevents the occurrence of diseases such as colorectal tumors and participates in the regulation of intestinal flora [23]. It has been reported that NLRP6 is highly expressed in intestinal epithelial cells where the activation of caspase-1 and ASC is also detected [18]. Furthermore, NLRP6 is also expressed in different immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells [20], indicating the key role of NLRP6 in the host. Although the importance of NLRP6 in the host has been studied, the role of NLRP6 in the lung inflammation is less studied. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the role of NLRP6 in the host against S. pneumoniae.

Immune cells including macrophages can trigger acute inflammation and secrete IL-1β, which plays an important role in protecting the host from pneumococcal pneumonia [24][25]. At the same time, IL-1β can mediate the expression of chemokines and the synthesis of fibrinogen as well as adhesion molecules to limit the spread of bacteria, resulting in a decreased burden of bacteria [26][27][28]. It has been reported that IL-1β secretion is required the activation of inflammasomes. Hara et al. showed that NLRP6 is involved in the secretion of IL-1β, IL-18 and IL-6 during L. monocytogenes- and S. aureus-infected bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) [21]. Similarly, our study showed that NLRP6 mediates the secretion of IL-1β and IL-6 during macrophages infection with S. pneumoniae. However, knockout of NLRP6 did not affect the S. pneumoniae-induced expression of IL-1β mRNA and formation of total IL-1β in this study, which is consistent with the study that found blocking NLRP6 did not change LPS-induced expression of IL-1β mRNA and protein [29]. In our previous studies, S. pneumoniae-induced secretion of IL-1β also depended on the activation of AIM2 and NLRP3 inflammasomes [12][16][30]. In this study, in spite of knockout of NLRP6 in the macrophages, the existence of other inflammasomes such as NLRP3 and AIM2 might contribute to the unchanged IL-1β during S. pneumoniae infection. In contrast with our’s and Hara’s results that knockout of NLRP6 reduced the IL-6 production, Anand et al. found that knockout of NLRP6 increased L. monocytogenes-induced IL-6 expression [20]. Although the secretion of IL-6 is inflammasome-independent, it is also mediated by NLRP6 in different microbial challenges. Van Scheppingen J, et al. showed that the decrease of IL-1β may lead to the reduction of IL-6 [31]. Therefore, the decrease of IL-6 might be post-transductional modifications or other possibilities. However, the exact mechanism underlying decreased IL-6 and IL-12p40 in S. pneumoniae-infected NLRP6−/− macrophages and mice needs to be further explored.

It has been shown that overexpression of NLRP6 induced activation of caspase-1 and GSDMD leads to secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 [32]. Furthermore, Hara et al. found that lipoteichoic acid (LTA)-induced activation of NLRP6 promoted processing of caspase-11 and the activation of capase-1, resulting in secretion of IL-1β and IL-18. During this process, the adaptor ASC plays an important role in the recruitment of caspase-1 and caspase-11 [21]. Similarly, our study also suggested that NLRP6 inflammasome induced by S. pneumoniae can promote the activation of caspase-11, caspase-1, and GSDMD. Notably, knocking out ASC remarkably decreased the activation of caspase-11, suggesting that NLRP6-mediated activation of caspase-11 is dependent on the formation of ASC.

NF-κB is a family of nuclear transcriptional regulators and plays an important role in regulating initial inflammatory response. It has been identified that NLRP6 specifically inhibited the activation of NF-κB and ERK signaling pathways in response to L. monocytogenes, Pam3CSK4, or LPS [20]. Moreover, NLRP6 deficiency leads to upregulation of p-p38 MAPK, p-ERK, and p-IκBα in some diseases, such as allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) [33], peripheral nerve injury [34], and acute kidney injury (AKI) [35]. These results are similar to our study in which the expression of p-p65, p-IκBα, and p-ERK induced by S. pneumoniae was downregulated in NLRP6−/− macrophages, suggesting NLRP6 negatively regulates the inflammatory NF-κB and ERK signaling pathways.

Several groups have reported that after S. aureus infection the survival of NLRP6−/− mice was significantly higher than WT mice [21][22], which is similar to our results that S. pneumoniae-infected NLRP6−/− mice had lower mortality. In our current study, NLRP6−/− mice showed lower bacterial loads and milder inflammation in the lung after S. pneumoniae infection compare with WT mice, indicating the negative role of NLRP6 in the clearance of bacteria. Our results confirmed that NLRP6 knockout increased the clearance of S. pneumoniae by increasing the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages. A similar phenomenon was found in NLRP6−/− mice infected with S. aureus, which showed that NLRP6 serves as a negative regulator in the host by modulating the recruitment of neutrophils [22]. Importantly, consistent with the results of in vitro experiments, the secretion of IL-1β and IL-6 were also decreased in the BALF of NLRP6−/− mice. It has been reported that NLRP6−/− cells produced elevated levels of NF-κB- and MAPK-dependent cytokines and chemokines against pathogens [21]. In this study, NLRP6-mediated inhibition of inflammatory signaling pathways in vitro probably leads to damage of the inflammatory response after S. pneumoniae infection. However, further study will be needed to explore the NLRP6-mediated inhibition of NF-κB and ERK signal pathways in vivo.

In conclusion, we investigated the role of NLRP6 in the host against S. pneumoniae both in vivo and in vitro. NLRP6 mediated S. pneumoniae-induced secretion of IL-1β, which was dependent on activation of caspase-1 and caspase-11. However, NLRP6 negatively regulated the inflammatory signaling pathway in S. pneumoniae-infected macrophages. Furthermore, NLRP6 deficient mice showed low mortality against S. pneumoniae infection, indicating the negative role of NLRP6 in regulating inflammatory response against microbial infection. These findings provide further insights into the role of NLRP6 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory response in the host defense against S. pneumoniae infection.

References

- Bittaye, M.; Cash, P. Streptococcus pneumoniae proteomics: Determinants of pathogenesis and vaccine development. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2015, 12, 607–621.

- Weiser, J.N.; Ferreira, D.M.; Paton, J.C. Streptococcus pneumoniae: Transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 16, 355–367.

- Mitchell, A.M.; Mitchell, T.J. Streptococcus pneumoniae: Virulence factors and variation. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 411–418.

- Koppe, U.; Suttorp, N.; Opitz, B. Recognition of Streptococcus pneumoniae by the innate immune system. Cell. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 460–466.

- Brooks, L.R.K.; Mias, G.I. Streptococcus pneumoniae’s Virulence and Host Immunity: Aging, Diagnostics, and Prevention. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1366.

- Vernatter, J.; Pirofski, L.-A. Current concepts in host–microbe interaction leading to pneumococcal pneumonia. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 26, 277–283.

- Lamkanfi, M.; Dixit, V.M. Mechanisms and Functions of Inflammasomes. Cell 2014, 157, 1013–1022.

- Tsuchiya, K.; Hara, H. The Inflammasome and Its Regulation. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 34, 41–80.

- Zhou, H.; Coveney, A.P.; Wu, M.; Huang, J.; Blankson, S.; Zhao, H.; O’Leary, D.P.; Bai, Z.; Li, Y.; Redmond, H.P.; et al. Activation of Both TLR and NOD Signaling Confers Host Innate Immunity-Mediated Protection Against Microbial Infection. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3082.

- Kumar, H.; Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Pathogen Recognition by the Innate Immune System. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 30, 16–34.

- Man, S.M.; Kanneganti, T.-D. Regulation of inflammasome activation. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 265, 6–21.

- Platnich, J.M.; Muruve, D.A. NOD-like receptors and inflammasomes: A review of their canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 670, 4–14.

- Downs, K.P.; Nguyen, H.; Dorfleutner, A.; Stehlik, C. An overview of the non-canonical inflammasome. Mol. Asp. Med. 2020, 76, 100924.

- Fang, R.; Tsuchiya, K.; Kawamura, I.; Shen, Y.; Hara, H.; Sakai, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Fernandes-Alnemri, T.; Yang, R.; Hernandez-Cuellar, E.; et al. Critical Roles of ASC Inflammasomes in Caspase-1 Activation and Host Innate Resistance to Streptococcus pneumoniae Infection. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 4890–4899.

- Koppe, U.; Hogner, K.; Doehn, J.M.; Muller, H.C.; Witzenrath, M.; Gutbier, B.; Bauer, S.; Pribyl, T.; Hammerschmidt, S.; Lohmeyer, J.; et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae stimulates a STING- and IFN regulatory factor 3-dependent type I IFN pro-duction in macrophages, which regulates RANTES production in macrophages, cocultured alveolar epithelial cells, and mouse lungs. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 811–817.

- Feng, S.; Chen, T.; Lei, G.; Hou, F.; Jiang, J.; Huang, Q.; Peng, Y.; Ye, C.; Hu, D.-L.; Fang, R. Absent in melanoma 2 inflammasome is required for host defence against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Innate Immun. 2019, 25, 412–419.

- Witzenrath, M.; Pache, F.; Lorenz, D.; Koppe, U.; Gutbier, B.; Tabeling, C.; Reppe, K.; Meixenberger, K.; Dorhoi, A.; Ma, J. The NLRP3 inflammasome is differentially activated by pneumolysin variants and contributes to host defense in pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 434–440.

- Levy, M.; Thaiss, C.A.; Zeevi, D.; Dohnalová, L.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Mahdi, J.A.; David, E.; Savidor, A.; Korem, T.; Herzig, Y.; et al. Microbiota-Modulated Metabolites Shape the Intestinal Microenvironment by Regulating NLRP6 Inflammasome Signaling. Cell 2015, 163, 1428–1443.

- Wlodarska, M.; Thaiss, C.A.; Nowarski, R.; Henao-Mejia, J.; Zhang, J.-P.; Brown, E.M.; Frankel, G.; Levy, M.; Katz, M.N.; Philbrick, W.M.; et al. NLRP6 Inflammasome Orchestrates the Colonic Host-Microbial Interface by Regulating Goblet Cell Mucus Secretion. Cell 2014, 156, 1045–1059.

- Anand, P.K.; Malireddi, R.K.S.; Lukens, J.R.; Vogel, P.; Bertin, J.; Lamkanfi, M.; Kanneganti, T.-D. NLRP6 negatively regulates innate immunity and host defence against bacterial pathogens. Nature 2012, 488, 389–393.

- Hara, H.; Seregin, S.S.; Yang, D.; Fukase, K.; Chamaillard, M.; Alnemri, E.S.; Inohara, N.; Chen, G.Y.; Núñez, G. The NLRP6 Inflammasome Recognizes Lipoteichoic Acid and Regulates Gram-Positive Pathogen Infection. Cell 2018, 175, 1651–1664.

- Ghimire, L.; Paudel, S.; Jin, L.; Baral, P.; Cai, S.; Jeyaseelan, S. NLRP6 negatively regulates pulmonary host defense in Gram-positive bacterial infection through modulating neutrophil recruitment and function. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007308.

- Ghimire, L.; Paudel, S.; Jin, L.; Jeyaseelan, S. The NLRP6 inflammasome in health and disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 388–398.

- Anne, R.; Norbert, S.; Bastian, O. Inflammasomes in Pneumococcal Infection: Innate Immune Sensing and Bacterial Evasion Strategies. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 397, 215–227.

- LaRock, C.N.; Nizet, V. Inflammasome/IL-1beta Responses to Streptococcal Pathogens. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 518.

- Borthwick, L.A. The IL-1 cytokine family and its role in inflammation and fibrosis in the lung. Semin. Immunopathol. 2016, 38, 517–534.

- Lemon, J.K.; Miller, M.R.; Weiser, J.N. Sensing of Interleukin-1 Cytokines during Streptococcus pneumoniae Colonization Contributes to Macrophage Recruitment and Bacterial Clearance. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 3204–3212.

- Surabhi, S.; Cuypers, F.; Hammerschmidt, S.; Siemens, N. The Role of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Pneumococcal Infections. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 614801.

- Lu, W.L.; Zhang, L.; Song, D.Z.; Yi, X.W.; Xu, W.Z.; Ye, L.; Huang, D.M. NLRP6 suppresses the inflammatory response of human periodontal ligament cells by inhibiting NF-κB and ERK signal pathways. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 999–1009.

- Zhang, T.; Du, H.; Feng, S.; Wu, R.; Chen, T.; Jiang, J.; Peng, Y.; Ye, C.; Fang, R. NLRP3/ASC/Caspase-1 axis and serine protease activity are involved in neutrophil IL-1β processing during Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 513, 675–680.

- Van Scheppingen, J.; Mills, J.D.; Zimmer, T.S.; Broekaart, D.W.M.; Iori, V.; Bongaarts, A.; Anink, J.J.; Iyer, A.M.; Korotkov, A.; Jansen, F.E.; et al. miR147b: A novel key regulator of in-terleukin 1 beta-mediated inflammation in human astrocytes. Neural Inj. Funct. Reconstr. 2018, 66, 1082–1097.

- Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, X. NLRP6 Induces Pyroptosis by Activation of Caspase-1 in Gingival Fibroblasts. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 1391–1398.

- Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Shi, J.; Ju, W.; Qi, K.; Fu, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, J.; Xu, K.; et al. NLRP6 deficiency aggravates liver injury after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 74, 105740.

- Ydens, E.; Demon, D.; Lornet, G.; De Winter, V.; Timmerman, V.; Lamkanfi, M.; Janssens, S. Nlrp6 promotes recovery after peripheral nerve injury independently of inflammasomes. J. Neuroinflamm. 2015, 12, 143.

- Valio-Rivas, L.; Cuarental, L.; Nuez, G.; Sanz, A.B.; Sanchez-Nio, M.D. Loss of NLRP6 expression increases the severity of acute kidney injury. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 35, 587–598.