O-GlcNAcylation is a post-translational modification that dynamically modifies serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) residues of nuclear and cytoplasmic

proteins through their hydroxyl moieties. O-GlcNAcylation is catalyzed by two key enzymes, namely, O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA), which add/remove UDP-GlcNAc to/from Ser and Thr residues, respectively. O-GlcNAc modification is dependent on the intracellular concentration of UDP-GlcNAc from the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, which integrates carbohydrates, amino acids, fatty acids and nucleic acids metabolism in the process of UPD-GlcNAc synthesis. Protein O-GlcNAcylation is widely recognized as an important cellular nutrient sensor and it may represents a key linkage between nutrient sensing, energy metabolism and signal transduction.

- high-fat diet

- brain insulin resistance

- neurodegeneration

- protein O-GlcNAcylation

- mitochondria

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is a series of complex metabolic disorders centering on insulin resistance, obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, which represents a high-risk factor for a number of pathological conditions including Type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cognitive decline [1]. T2DM accounts for 90% of all reported diabetes cases [2,3] and it is attributed to the interaction of multiple genetic and environmental factors. One of the environmental risks is the modern lifestyle with the so-called Western diet, rich in refined carbohydrates, animal fats and edible oils, which leads to nutrient excess and promotes the development of insulin resistance [4]. Systemic and brain insulin resistance, as common features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and T2DM, play prominent roles in the development of cognitive dysfunction and dementia [5,6,7,8]. Epidemiologic studies indicate that long-term hyperinsulinemia and obesity, caused by dietary fat intake, are risk factors for dementia. Moreover, insulin administered to AD patients, by regulating glucose transport, energy metabolism, neuronal growth, and synaptic plasticity, improves memory formation [9,10,11]. Studies on mice fed with a high-fat diet (HFD), which mimicked a hypercaloric Western-style diet [12], thus leading to obesity and T2DM, demonstrated impaired performance in learning and memory tasks, alterations of synaptic integrity, altered CA1-related long-term depression (LTD) and long-term potentiation (LTP), and the development of AD pathological hallmarks [13,14,15,16]. However, the identification of the exact molecular mechanisms associating perturbations in the peripheral environment with brain function is unclear and effective treatments are lacking. Thus, there is an urgent need to further explore the molecular role of insulin resistance in order to find innovative strategies and key targets for the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome. In this scenario, as the nutrient-sensing mechanisms are essential for regulation of metabolism, it might be of great significance to explore the biological mechanisms that link insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and neurodegeneration from the perspective of nutrient recognition and regulation.

Metabolic syndrome is a series of complex metabolic disorders centering on insulin resistance, obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, which represents a high-risk factor for a number of pathological conditions including Type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cognitive decline [1]. T2DM accounts for 90% of all reported diabetes cases [2][3] and it is attributed to the interaction of multiple genetic and environmental factors. One of the environmental risks is the modern lifestyle with the so-called Western diet, rich in refined carbohydrates, animal fats and edible oils, which leads to nutrient excess and promotes the development of insulin resistance [4]. Systemic and brain insulin resistance, as common features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and T2DM, play prominent roles in the development of cognitive dysfunction and dementia [5][6][7][8]. Epidemiologic studies indicate that long-term hyperinsulinemia and obesity, caused by dietary fat intake, are risk factors for dementia. Moreover, insulin administered to AD patients, by regulating glucose transport, energy metabolism, neuronal growth, and synaptic plasticity, improves memory formation [9][10][11]. Studies on mice fed with a high-fat diet (HFD), which mimicked a hypercaloric Western-style diet [12], thus leading to obesity and T2DM, demonstrated impaired performance in learning and memory tasks, alterations of synaptic integrity, altered CA1-related long-term depression (LTD) and long-term potentiation (LTP), and the development of AD pathological hallmarks [13][14][15][16]. However, the identification of the exact molecular mechanisms associating perturbations in the peripheral environment with brain function is unclear and effective treatments are lacking. Thus, there is an urgent need to further explore the molecular role of insulin resistance in order to find innovative strategies and key targets for the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome. In this scenario, as the nutrient-sensing mechanisms are essential for regulation of metabolism, it might be of great significance to explore the biological mechanisms that link insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and neurodegeneration from the perspective of nutrient recognition and regulation.

In this regard, protein O-GlcNAcylation is widely recognized as an important cellular nutrient sensor and it serves as a key linkage between nutrient sensing, energy metabolism and signal transduction [17]. O-GlcNAcylation is a post-translational modification that dynamically modifies serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) through their hydroxyl moieties on nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins [18]. O-GlcNAcylation is catalyzed by two key enzymes, namely, O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA), which add/remove UDP-GlcNAc to/from Ser and Thr residues, respectively [19]. O-GlcNAc modification is dependent on the intracellular concentration of UDP-GlcNAc from the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP). The HBP integrates the metabolic information of nutrients, including carbohydrates, amino acids, fatty acids, and nucleic acids, in the process of UPD-GlcNAc synthesis [4]. Further, HBP regulates energy homeostasis by controlling the production of both insulin and leptin, which are hormones playing a critical role in regulating energy metabolism [20]. O-GlcNAcylation is tightly coupled to insulin resistance because hyperglycemia or hyperlipidemia-induced insulin resistance is closely related to altered HBP flux, and in turn, the subsequent aberrant O-GlcNAcylation modifies insulin signaling, glucose uptake, gluconeogenesis, glycogen, and fatty acid synthesis [21]. In this scenario, O-GlcNAcylation represents a key mechanism linking nutrient overload and insulin resistance, and their dysregulation might promote the transition from metabolic defects to chronic diseases such as T2DM and AD [22,23,24,25,26]. Indeed, obesity and peripheral hyperglycemia, by promoting insulin resistance and hypoglycemia at brain level, lead to decreased O-GlcNAcylation of APP and Tau and to increased production of toxic Aβ amyloid and Tau aggregates, which are hallmarks of AD [27,28,29,30,31]. Furthermore, the well-known involvement of O-GlcNAcylation in controlling protein localization, function, and interaction has acquired special interest with regards to APP. Indeed, this posttranslational modification (PTM) has been demonstrated to control APP maturation and trafficking, thus affecting the generation Aβ [32,33,34]. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction and the associated oxidative stress have been recognized as important biological mechanisms contributing to insulin resistance and diabetic complications [35,36,37,38]. As well, a number of studies demonstrated that impaired mitochondrial function plays a significant role in neurodegenerative diseases, supporting the notion that AD is primarily a metabolic disorder [14,39,40,41,42,43]. O-GlcNAcylation is known to regulate energy metabolism and the production of metabolic intermediates through the dynamic modulation of mitochondrial function, motility, and distribution. Past and present proteomics analysis revealed the presence of O-GlcNAc-modified mitochondrial proteins in different rodents’ organs (e.g., brain) supporting that the overexpression of OGT or OGA proteins alters mitochondrial proteome and severely affects mitochondrial morphology and metabolic processes [44,45,46]. Further, hyperglycemia was associated with the aberrant O-GlcNAcylation of mitochondrial protein and with the modulation of the electron transport chain activity, oxygen consumption rate, ATP production, and calcium uptake in cardiac myocytes [44,47,48]. Thus, aberrant protein O-GlcNAcylation and its regulation of mitochondrial proteins might represent the missing link between metabolic defects and neurodegeneration occurring in T2DM and AD. Therefore, the present study aimed to decipher the role of O-GlcNAcylation and associated mitochondrial abnormalities in mediating the development of AD signatures in HFD mice by exploring how nutrient excess leads to the alteration of both OGT/OGA cycle and of energy consumption/production, thus promoting the development of AD hallmarks.

In this regard, protein O-GlcNAcylation is widely recognized as an important cellular nutrient sensor and it serves as a key linkage between nutrient sensing, energy metabolism and signal transduction [17]. O-GlcNAcylation is a post-translational modification that dynamically modifies serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) through their hydroxyl moieties on nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins [18]. O-GlcNAcylation is catalyzed by two key enzymes, namely, O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA), which add/remove UDP-GlcNAc to/from Ser and Thr residues, respectively [19]. O-GlcNAc modification is dependent on the intracellular concentration of UDP-GlcNAc from the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP). The HBP integrates the metabolic information of nutrients, including carbohydrates, amino acids, fatty acids, and nucleic acids, in the process of UPD-GlcNAc synthesis [4]. Further, HBP regulates energy homeostasis by controlling the production of both insulin and leptin, which are hormones playing a critical role in regulating energy metabolism [20]. O-GlcNAcylation is tightly coupled to insulin resistance because hyperglycemia or hyperlipidemia-induced insulin resistance is closely related to altered HBP flux, and in turn, the subsequent aberrant O-GlcNAcylation modifies insulin signaling, glucose uptake, gluconeogenesis, glycogen, and fatty acid synthesis [21]. In this scenario, O-GlcNAcylation represents a key mechanism linking nutrient overload and insulin resistance, and their dysregulation might promote the transition from metabolic defects to chronic diseases such as T2DM and AD [22][23][24][25][26]. Indeed, obesity and peripheral hyperglycemia, by promoting insulin resistance and hypoglycemia at brain level, lead to decreased O-GlcNAcylation of APP and Tau and to increased production of toxic Aβ amyloid and Tau aggregates, which are hallmarks of AD [27][28][29][30][31]. Furthermore, the well-known involvement of O-GlcNAcylation in controlling protein localization, function, and interaction has acquired special interest with regards to APP. Indeed, this posttranslational modification (PTM) has been demonstrated to control APP maturation and trafficking, thus affecting the generation Aβ [32][33][34]. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction and the associated oxidative stress have been recognized as important biological mechanisms contributing to insulin resistance and diabetic complications [35][36][37][38]. As well, a number of studies demonstrated that impaired mitochondrial function plays a significant role in neurodegenerative diseases, supporting the notion that AD is primarily a metabolic disorder [14][39][40][41][42][43]. O-GlcNAcylation is known to regulate energy metabolism and the production of metabolic intermediates through the dynamic modulation of mitochondrial function, motility, and distribution. Past and present proteomics analysis revealed the presence of O-GlcNAc-modified mitochondrial proteins in different rodents’ organs (e.g., brain) supporting that the overexpression of OGT or OGA proteins alters mitochondrial proteome and severely affects mitochondrial morphology and metabolic processes [44][45][46]. Further, hyperglycemia was associated with the aberrant O-GlcNAcylation of mitochondrial protein and with the modulation of the electron transport chain activity, oxygen consumption rate, ATP production, and calcium uptake in cardiac myocytes [44][47][48]. Thus, aberrant protein O-GlcNAcylation and its regulation of mitochondrial proteins might represent the missing link between metabolic defects and neurodegeneration occurring in T2DM and AD. Therefore, the present study aimed to decipher the role of O-GlcNAcylation and associated mitochondrial abnormalities in mediating the development of AD signatures in HFD mice by exploring how nutrient excess leads to the alteration of both OGT/OGA cycle and of energy consumption/production, thus promoting the development of AD hallmarks.

2. HFD Mice Show an Aberrant and Tissue-Specific O-GlcNAcylation Profile

In the present study, we aimed to explore the impact of nutrient overload in promoting putative changes of protein O-GlcNAcylation in the brain of mice fed with a diet rich in fat content (HFD) in comparison to aged-matched animals that received a standard diet (SD).

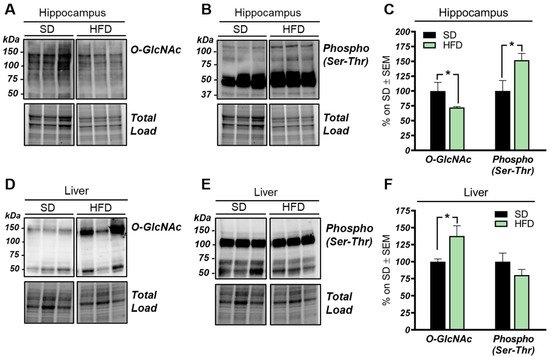

Our analysis of total O-GlcNAcylated protein levels in the hippocampus of HFD mice revealed a significant reduction if compared to the total O-GlcNAcylation levels observed in the same brain region from SD mice (

Figure 1A–C; *

p < 0.05, SD vs. HFD: −28%). In line with the well-known competition occurring between protein O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation [49,50,51], we also observed an increase of total protein serine/threonine phosphorylation (< 0.05, SD vs. HFD: −28%). In line with the well-known competition occurring between protein O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation [49][50][51], we also observed an increase of total protein serine/threonine phosphorylation (

Figure 1A–C; *

p < 0.02, SD vs. HFD: +52%). Since HFD is a well-established model of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance [52], we also evaluated the O-GlcNAcylation of liver proteome from HFD mice. Hyperglycemia and dysfunctional insulin signaling have been associated, in peripheral organs, with increased levels of O-GlcNAcylated proteins [53,54]. In agreement, we observed a significant increase in the total O-GlcNAcylated protein levels in the liver of HFD mice in comparison to the control group (< 0.02, SD vs. HFD: +52%). Since HFD is a well-established model of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance [52], we also evaluated the O-GlcNAcylation of liver proteome from HFD mice. Hyperglycemia and dysfunctional insulin signaling have been associated, in peripheral organs, with increased levels of O-GlcNAcylated proteins [53][54]. In agreement, we observed a significant increase in the total O-GlcNAcylated protein levels in the liver of HFD mice in comparison to the control group (

Figure 1D,F; *

p< 0.02, SD vs. HFD: +38%). Meanwhile, in regards to protein phosphorylation, we demonstrated a slight nonsignificant decrease in serine/threonine in the liver from HFD mice compared to SD mice (

Figure 1D–F; SD vs. HFD: −20%).

O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation profile in the hippocampus and liver from high-fat diet (HFD) mice. (

): O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation profile in the hippocampus from HFD mice compared to a respective standard diet (SD) animals. The reduction of protein O-GlcNAcylation in the hippocampus of HFD mice was in line with a mutual inverse increase in the global phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues compared to SD controls. Representative blots are reported in (

,

). (

): O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation profile in the liver of HFD mice compared to respective control group. Increased levels of O-GlcNAcylated proteins were observed in the liver of HFD compared to animals fed with a SD, confirming a global imbalance of O-GlcNAcylation homeostasis in peripheral organs of our model. A trend of increase was observed in the phosphorylation of serine and threonine of hepatic proteins from HFD in comparison to SD mice. Representative blots are reported in (

,

). Number of animals for each condition were as follow:

= 6/group for Western blot. All bar charts reported in (

,

) show mean ± SEM. *

< 0.05, using Student’s t test.

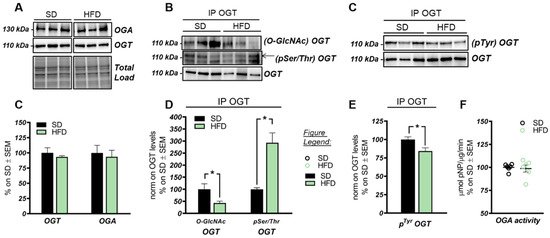

These data suggest that the O-GlcNAcylation profile was completely opposite to that examined in the hippocampus and that a direct competition between O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation may only occur at brain level, while peripheral alterations are mainly associated with the increase of protein O-GlcNAcylation. These results follow previous data collected in Down syndrome mice [55] and are in line with the notion that the aberrant increase of peripheral O-GlcNAcylation levels might be related to insulin resistance and to hyperglycemia-induced glucose toxicity [56]. Afterwards, we evaluated potential alterations occurring on the O-GlcNAc enzymatic machinery with the aim of assessing whether the reduced levels of O-GlcNAcylated proteins in the hippocampus of HFD mice could be the result of the altered OGT/OGA functionality. In details, we did not observe any relevant changes, either in OGT or OGA protein expression levels, in the hippocampus of our HFD model (

Figure 2A,C). Considering the role of OGT as a sensor of cellular metabolic state [57,58], we further analyzed OGT PTMs through immunoprecipitation to evaluate the effects of nutrient surplus on its functionality. Interestingly, we observed a significant reduction ofA,C). Considering the role of OGT as a sensor of cellular metabolic state [57][58], we further analyzed OGT PTMs through immunoprecipitation to evaluate the effects of nutrient surplus on its functionality. Interestingly, we observed a significant reduction of

O-GlcNAcOGT levels in the hippocampi of mice with a HFD (

Figure 2B,D; *

p< 0.05, SD vs. HFD: −57%), together with a substantial increase of

pSer/ThrOGT levels in our HFD model compared to the same brain region of SD animals (

Figure 2B,D; *

p< 0.05, SD vs. HFD: +193%). The aberrant changes of OGT Ser/Thr PTMs observed by us may suggest a potential imbalance of the O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation ratio, which may involve specific catalytic and/or regulatory residues of OGT. Despite the fact that involvement of serine residues was reported to regulate OGT function, studies by Hart laboratory supported the idea that OGT activity is mostly regulated by the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues [59]. Our analysis of total

pTyrOGT levels demonstrated a significant reduction in HFD mice hippocampi (

Figure 3C,E; *

p< 0.05, SD vs. HFD: −15%), supporting the notion of altered OGT’s enzymatic ability to transfer O-GlcNAc moiety. In contrast, OGA did not show any variation in its enzymatic functionality (

Figure 2F), excluding a role for this enzyme in the reduction of O-GlcNAcylation levels in HFD mice.

OGT/OGA functionality in the hippocampus of HFD mice. (

,

) OGT and OGA protein levels in HFD mice hippocampi. No relevant changes were observed in the protein expression levels of the enzymes controlling O-GlcNAc cycling. Representative blots are reported in (

). (

,

) Evaluation of OGT’s posttranslational modifications(PTMs) by immunoprecipitation analysis. A significant reduction in

OGT/OGT levels, together with a consistent increase in its

OGT/OGT levels, were observed in the hippocampi of HFD mice in comparison to the same brain region from SD mice. Representative blots are reported in (

). (

,

) Evaluation of OGT phosphorylation on Tyr residues. A significant reduction was observed in HFD mice compared to respective SD group, suggesting an alteration of OGT functionality. Representative blots are reported in (

). (

): OGA activity assay. No changes were observed in OGA enzymatic activity between the two experimental groups. Number of animals for each condition were as follows:

= 6/group for Western blot and OGA assay analysis while

= 3/group was used for immunoprecipitation analysis. All bar charts reported in (

–

), and (

) show mean ± SEM. *

< 0.05 using Student’s t test.

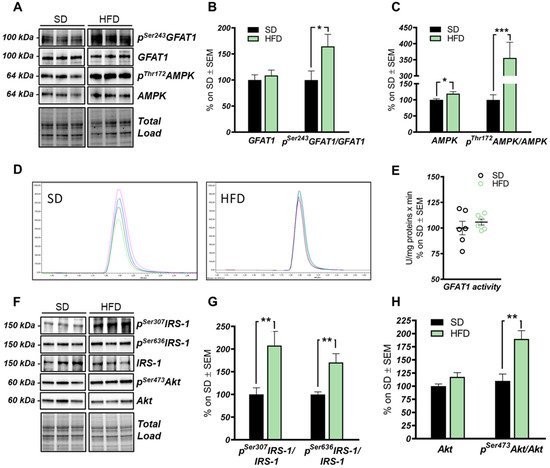

The hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP) flux is impaired in the hippocampus of HFD mice. (

,

): Analysis of GFAT1 activation status in HFD mice compared to respective controls. A significantly increased p

GFAT1/GFAT1 ratio was observed in HFD mice compared to SD, thus resulting in the inhibition of GFAT1 activity. Representative blots are reported in (

). (

,

) Analysis of AMPK activation status in HFD mice compared to respective SD animals. A significant increase in the AMPK protein levels was observed in HFD, together with a relevant increase in p

AMPK/AMPK levels, thus resulting in increased AMPK activation. Representative blots are reported in (

). (

,

) GFAT1 activity assay. No relevant changes were observed in GFAT1’s ability to synthetize glucosamine-6-phosphate in vitro between the HFD group and SD mice. Representative spectra of GFAT1-synthetized glucosamine-6-phosphate for both HFD and SD animals are reported in (

). (

,

) Analysis of the IRS-1 activation state in the hippocampi of HFD mice compared to SD-fed animals. A relevant increase in both p

IRS-1/IRS-1 and p

IRS-1/IRS-1 levels was observed, suggesting a reduction in IRS-1 activation in HFD mice compared to SD. Representative blots are reported in (

). (

,

) Analysis of Akt activation status in HFD mice compared to respective controls. p

Akt/Akt ratio was significantly increased in the HFD hippocampal region compared to the same brain area of SD mice. Number of animals for each condition were as follow:

= 6/group for both Western blot analysis and GFAT1 activity assay. All bar charts reported in (

,

) and (

,

) show mean ± SEM. *

< 0.05, **

< 0.01, ***

< 0.001 using Student’s t test.

3. The HBP Flux Is Impaired in HFD Mice Compared to SD

The HBP pathway integrates multiple metabolic pathways into the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc, providing feedback on overall cellular energy levels and nutrient availability [60]. In this scenario, increased flux of metabolites into the HBP have already been highlighted as a key point driving metabolic alterations in the skeletal muscle of a model of fat-induced insulin resistance [61]. GFAT1 is the rate-limiting enzyme that coordinates nutrients’ entrance into the HBP flux, and it is negatively regulated by AMPK upon its activation [62,63]. The analysis of the HFD hippocampus has demonstrated a significant increase of Ser243 inhibitory phosphorylation of GFAT1 compared to a respective control group (

The HBP pathway integrates multiple metabolic pathways into the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc, providing feedback on overall cellular energy levels and nutrient availability [60]. In this scenario, increased flux of metabolites into the HBP have already been highlighted as a key point driving metabolic alterations in the skeletal muscle of a model of fat-induced insulin resistance [61]. GFAT1 is the rate-limiting enzyme that coordinates nutrients’ entrance into the HBP flux, and it is negatively regulated by AMPK upon its activation [62][63]. The analysis of the HFD hippocampus has demonstrated a significant increase of Ser243 inhibitory phosphorylation of GFAT1 compared to a respective control group (

A,B; *

p

< 0.05, SD vs. HFD: +65%). No relevant changes were observed in GFAT1 protein expression levels between the two groups (

A,B). In line with these data, HFD mice showed the increase of AMPK-activating phosphorylation on Thr172 compared to animals that have been fed with a SD (

A,C; ***

p

< 0.001, SD vs. HFD: +255%), together with a significant increase in AMPK protein levels in HFD mice (

A,C; *

p < 0.05, SD vs. HFD: +20%). AMPK is known to inhibit GFAT1 activity under nutrient depletion or stress conditions via its phosphorylation on Ser243, in order to reduce the amount of nutrients entering the HBP flux [62,63,64]. Interestingly, by testing GFAT1’s ability to synthetize glucosamine-6-phosphate in vitro by HPLC, we did not observe significant changes between HFD hippocampal extract and respective SD controls (

< 0.05, SD vs. HFD: +20%). AMPK is known to inhibit GFAT1 activity under nutrient depletion or stress conditions via its phosphorylation on Ser243, in order to reduce the amount of nutrients entering the HBP flux [62][63][64]. Interestingly, by testing GFAT1’s ability to synthetize glucosamine-6-phosphate in vitro by HPLC, we did not observe significant changes between HFD hippocampal extract and respective SD controls (

D,E). Since the GFAT1 activity assay was carried out in a large excess of substrates [65], the reduced GFAT1 activation (measured as increased

pSer243

GFAT1/GFAT1 levels) may result from reduced substrate availability in the intracellular environment. These findings suggest that HFD may lead to the reduction of nutrient uptake (i.e., glucose) in the brain, promoting AMPK-mediated inhibition of GFAT1, finally resulting in reduced synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc through the HBP and decreased protein O-GlcNAcylation in the hippocampus of HFD mice. The reduction of brain insulin sensitivity is one of the most well-known causes of HFD-induced cognitive decline. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that insulin resistance could favor nutrient depletion and that AMPK-mediated inhibition of GFAT1 mice might be associated with the development of brain insulin resistance.

In detail, we observed an increase of IRS-1 phosphorylation on its inhibitory sites (Ser307 and 636) [66,67] in the hippocampus of HFD mice in comparison to standard-fed animals (

In detail, we observed an increase of IRS-1 phosphorylation on its inhibitory sites (Ser307 and 636) [66][67] in the hippocampus of HFD mice in comparison to standard-fed animals (

F,G; **

p

< 0.01, SD vs. HFD: +108% and +70%). Furthermore, a substantial increase in p

Ser473

Akt levels was detected in the hippocampus of the model examined compared to the control group (

F,H; **

p

< 0.01, SD vs. HFD: +73%) without affecting Akt protein expression levels between the two groups (

Figure 3F,H). These data show an alteration of the insulin signaling pathway, characterized by the uncoupling between IRS1 and Akt, in agreement with previous studies [6,14,66,67].

F,H). These data show an alteration of the insulin signaling pathway, characterized by the uncoupling between IRS1 and Akt, in agreement with previous studies [6][14][66][67].

4. Discussion

Studies on the high-fat-diet (HFD) model have largely demonstrated a strong correlation between the consumption of an hypercaloric diet and consequent alterations in brain functionality [75,76,77,78]. However, the exact molecular mechanisms that link perturbations of peripheral metabolism with brain alterations driving cognitive decline are still under discussion. Protein O-GlcNAcylation is a post-translational modification of quite recent discovery that is extremely sensitive to nutrient fluctuations, thus it has been widely recognized as a key linkage between nutrient sensing, energy metabolism, and cellular functions [79,80]. Several lines of evidence have emphasized the role of aberrantly increased protein O-GlcNAcylation in driving glucose toxicity and chronic hyperglycemia-induced insulin resistance [56,60], major hallmarks of T2DM and obesity. In this regard, the HFD model closely recapitulates molecular changes occurring in the so-called metabolic syndrome, which manifests as hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance and precedes obesity and T2DM [52,81,82]. Our analysis of liver samples from HFD mice summarized the increase in protein O-GlcNAcylation already observed in the peripheral organs of diabetic individuals, confirming O-GlcNAcylation as a major trigger of glucose toxicity [56,83,84]. A completely different scenario is to be considered for the role of O-GlcNAcylation in the brain. A wide range of evidence has already demonstrated how a hypercaloric diet affects cognitive performances, promoting metabolic dysregulation in the brain in a way similar to diabetes [75,81,85,86]. In agreement, epidemiological and molecular studies have suggested that T2DM, obesity, and general defects in brain glucose metabolism predispose to poorer cognitive performance and rapid cognitive decline during ageing, favoring the onset of dementia [40,87,88]. In this scenario, the alteration of protein O-GlcNAcylation that we observed in the hippocampus from HFD mice, coupled with the aberrant increase in Ser/Thr phosphorylation levels, resemble the alterations observed in the brain of AD individuals [31,36,89,90,91], as well as, of AD and DS mouse models. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated the reduction of total protein O-GlcNAc levels in the brain from AD and DS mice, supporting its involvement in the early molecular mechanisms promoting the development of AD signatures [22,55,92]. In line with these reports, the analysis of rat brains fed a short-term HFD demonstrated the increase of Aβ deposition and p-tau, and decreased synaptic plasticity, suggesting that molecular mechanism underling the onset of cognitive decline in HFD mice may resemble those occurring in AD models [93]. Our current investigation of tau and APP PTMs show that the alteration of their O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation ratio may represent one of the molecular mechanisms involved in HFD-related neurodegeneration. In particular, the significant reduction of tau O-GlcNAcylation levels, associated with the pathological increase in Ser404 phosphorylation, suggest a contrition of reduced O-GlcNAc levels in promoting tau toxicity [94,95]. As well, decreased O-GlcNAc levels of APP was shown to favor amyloidogenic processing and Aβ deposition through the increase of APP phosphorylation [96,97], however no altered levels of APP phosphorylation were observed in our study, as well as no accumulation of soluble Aβ 1–42. Although most of the pathological alterations observed in HFD mice are similar to those of other neurodegeneration models, the mechanisms underlying disturbances of O-GlcNAc homeostasis in the brain of HFD mice have different origins. We previously observed in the hippocampus of a mouse model of DS, the hyperactivation of OGA [55], but HFD mice did not show any significant increase in the removal of O-GlcNAc moiety. Rather the attention must be focused on the observed alteration of the hippocampal metabolic status associated with the development of insulin resistance. Previous human and rodent data support diet-induced insulin resistance as one of the main mediators of cognitive deficit associated with high fat consumption [68,82,93]. In agreement, mice fed with a HFD exhibited a significant increase in obesity and lower glucose and insulin tolerance as compared to animals fed with a standard diet. These changes parallel the consistent alterations of the insulin signaling in the brain characterized by increased IRS1 inhibition and the uncoupling with Akt [68,82]. These molecular events are key features of brain insulin resistance [6,66,67,74] (

Studies on the high-fat-diet (HFD) model have largely demonstrated a strong correlation between the consumption of an hypercaloric diet and consequent alterations in brain functionality [68][69][70][71]. However, the exact molecular mechanisms that link perturbations of peripheral metabolism with brain alterations driving cognitive decline are still under discussion. Protein O-GlcNAcylation is a post-translational modification of quite recent discovery that is extremely sensitive to nutrient fluctuations, thus it has been widely recognized as a key linkage between nutrient sensing, energy metabolism, and cellular functions [72][73]. Several lines of evidence have emphasized the role of aberrantly increased protein O-GlcNAcylation in driving glucose toxicity and chronic hyperglycemia-induced insulin resistance [56][60], major hallmarks of T2DM and obesity. In this regard, the HFD model closely recapitulates molecular changes occurring in the so-called metabolic syndrome, which manifests as hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance and precedes obesity and T2DM [52][74][75]. Our analysis of liver samples from HFD mice summarized the increase in protein O-GlcNAcylation already observed in the peripheral organs of diabetic individuals, confirming O-GlcNAcylation as a major trigger of glucose toxicity [56][76][77]. A completely different scenario is to be considered for the role of O-GlcNAcylation in the brain. A wide range of evidence has already demonstrated how a hypercaloric diet affects cognitive performances, promoting metabolic dysregulation in the brain in a way similar to diabetes [68][74][78][79]. In agreement, epidemiological and molecular studies have suggested that T2DM, obesity, and general defects in brain glucose metabolism predispose to poorer cognitive performance and rapid cognitive decline during ageing, favoring the onset of dementia [40][80][81]. In this scenario, the alteration of protein O-GlcNAcylation that we observed in the hippocampus from HFD mice, coupled with the aberrant increase in Ser/Thr phosphorylation levels, resemble the alterations observed in the brain of AD individuals [31][36][82][83][84], as well as, of AD and DS mouse models. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated the reduction of total protein O-GlcNAc levels in the brain from AD and DS mice, supporting its involvement in the early molecular mechanisms promoting the development of AD signatures [22][55][85]. In line with these reports, the analysis of rat brains fed a short-term HFD demonstrated the increase of Aβ deposition and p-tau, and decreased synaptic plasticity, suggesting that molecular mechanism underling the onset of cognitive decline in HFD mice may resemble those occurring in AD models [86]. Our current investigation of tau and APP PTMs show that the alteration of their O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation ratio may represent one of the molecular mechanisms involved in HFD-related neurodegeneration. In particular, the significant reduction of tau O-GlcNAcylation levels, associated with the pathological increase in Ser404 phosphorylation, suggest a contrition of reduced O-GlcNAc levels in promoting tau toxicity [87][88]. As well, decreased O-GlcNAc levels of APP was shown to favor amyloidogenic processing and Aβ deposition through the increase of APP phosphorylation [89][90], however no altered levels of APP phosphorylation were observed in our study, as well as no accumulation of soluble Aβ 1–42. Although most of the pathological alterations observed in HFD mice are similar to those of other neurodegeneration models, the mechanisms underlying disturbances of O-GlcNAc homeostasis in the brain of HFD mice have different origins. We previously observed in the hippocampus of a mouse model of DS, the hyperactivation of OGA [55], but HFD mice did not show any significant increase in the removal of O-GlcNAc moiety. Rather the attention must be focused on the observed alteration of the hippocampal metabolic status associated with the development of insulin resistance. Previous human and rodent data support diet-induced insulin resistance as one of the main mediators of cognitive deficit associated with high fat consumption [91][75][86]. In agreement, mice fed with a HFD exhibited a significant increase in obesity and lower glucose and insulin tolerance as compared to animals fed with a standard diet. These changes parallel the consistent alterations of the insulin signaling in the brain characterized by increased IRS1 inhibition and the uncoupling with Akt [91][75]. These molecular events are key features of brain insulin resistance [6][66][67][92] (

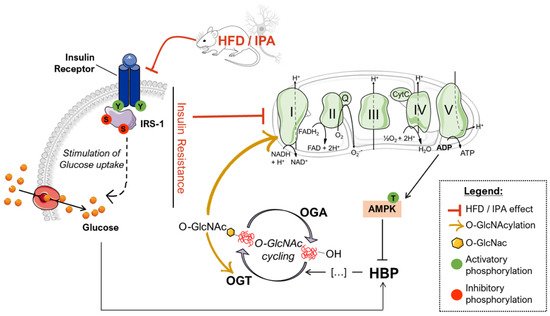

Figure 9). Indeed, as previously reported in HFD-treated mice, hyperactive Akt fails to further respond to insulin administration because of IRS-1 inhibition [14]. Interestingly, inhibitory serine residues of IRS1 can also be O-GlcNAcylated [22,98] leading to the possibility of reduced O-GlcNAcylation as one of the leading causes for IRS-1 hyperphosphorylation on inhibitory sites. Although it seems clear that the disruption of the balance between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation contributes to the unproper functioning of the insulin cascade, it should also be considered that the onset of insulin resistance might affect O-GlcNAc homeostasis by altering the number of metabolites available for the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc. In line with a metabolic profile characterized by low nutrient availability and increased AMP/ATP ratio, HFD mice showed a significant increase in AMPK activation (increased

4). Indeed, as previously reported in HFD-treated mice, hyperactive Akt fails to further respond to insulin administration because of IRS-1 inhibition [14]. Interestingly, inhibitory serine residues of IRS1 can also be O-GlcNAcylated [22][93] leading to the possibility of reduced O-GlcNAcylation as one of the leading causes for IRS-1 hyperphosphorylation on inhibitory sites. Although it seems clear that the disruption of the balance between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation contributes to the unproper functioning of the insulin cascade, it should also be considered that the onset of insulin resistance might affect O-GlcNAc homeostasis by altering the number of metabolites available for the synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc. In line with a metabolic profile characterized by low nutrient availability and increased AMP/ATP ratio, HFD mice showed a significant increase in AMPK activation (increased

pThr172AMPK levels). Most interestingly, AMPK-mediated inhibition of GFAT1 activity by its direct phosphorylation on Ser243 appears as one of the best-characterized mechanisms to reduce the amount of metabolites entering the HBP flux under nutrient depletion conditions [62,63,64]

AMPK levels). Most interestingly, AMPK-mediated inhibition of GFAT1 activity by its direct phosphorylation on Ser243 appears as one of the best-characterized mechanisms to reduce the amount of metabolites entering the HBP flux under nutrient depletion conditions [62][63][64]

,

matching the changes observed in HFD mice brains (

Figure 9). OGT is known to be phosphorylated by AMPK on Thr444, regulating both OGT selectivity and nuclear localization. Furthermore, the regulation of OGT expression and O-GlcNAc levels by AMPK seems to be highly dependent on cell type and pathological status, and glucose-deprivation was proven to favor OGT cytosolic localization upon AMPK activation [58,99,100,101]. Within this context, AMPK subunits have been shown to be dynamically modified by O-GlcNAc, which regulates their activation, showing a complex interplay between these enzymes [99]. Most interestingly, OGT O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation ratio was unbalanced in the hippocampus of HFD mice, suggesting the alteration of OGT function. Besides, the observed reduction of OGT phosphorylation on Tyr residues further supports the impairment of its activity, as suggested by Hart et al. [59]. According to this evidence, HFD-driven alterations of protein O-GlcNAcylation seems to be linked to reduced HBP flux and altered OGT PTMs, which contributes to aberrant O-GlcNAc cycling. In parallel to insulin resistance, HFD rodents also show altered mitochondrial functionality, oxidative stress, and reduced brain cortex bioenergetic [71,77,102]. In agreement, among the possible mechanisms by which nutrient overload exerts negative effects within the brain, the alteration of mitochondrial functionalities is among the most impactful. In a recent study, Chen et al. have shown an impaired expression of protein involved in mitochondrial dynamics, reduced Complex I–III activity and decreased mitochondrial respiration in HFD-treated rats [71]. Furthermore, a reduced AMP/ATP ratio in HFD rats demonstrated how diet-induced impairment of mitochondrial activity is reflected by the reduced ability to synthetize ATP as a source of energy [71]. In this scenario, data collected in the hippocampus of HFD mice are in line with recent studies on the topic, supporting that high fat consumption can affect mitochondria functionality, thus resulting in reduced respiratory capacity, decreased oxygen consumption, and reduced ATP production [77,102]. Indeed, we demonstrated in HFD mice, a significant reduction of both the expression levels and the activity of most respiratory chain complexes, especially Complex I, finally resulting in impaired ATP content in comparison to SD mice (

4). OGT is known to be phosphorylated by AMPK on Thr444, regulating both OGT selectivity and nuclear localization. Furthermore, the regulation of OGT expression and O-GlcNAc levels by AMPK seems to be highly dependent on cell type and pathological status, and glucose-deprivation was proven to favor OGT cytosolic localization upon AMPK activation [58][94][95][96]. Within this context, AMPK subunits have been shown to be dynamically modified by O-GlcNAc, which regulates their activation, showing a complex interplay between these enzymes [94]. Most interestingly, OGT O-GlcNAcylation/phosphorylation ratio was unbalanced in the hippocampus of HFD mice, suggesting the alteration of OGT function. Besides, the observed reduction of OGT phosphorylation on Tyr residues further supports the impairment of its activity, as suggested by Hart et al. [59]. According to this evidence, HFD-driven alterations of protein O-GlcNAcylation seems to be linked to reduced HBP flux and altered OGT PTMs, which contributes to aberrant O-GlcNAc cycling. In parallel to insulin resistance, HFD rodents also show altered mitochondrial functionality, oxidative stress, and reduced brain cortex bioenergetic [97][70][98]. In agreement, among the possible mechanisms by which nutrient overload exerts negative effects within the brain, the alteration of mitochondrial functionalities is among the most impactful. In a recent study, Chen et al. have shown an impaired expression of protein involved in mitochondrial dynamics, reduced Complex I–III activity and decreased mitochondrial respiration in HFD-treated rats [97]. Furthermore, a reduced AMP/ATP ratio in HFD rats demonstrated how diet-induced impairment of mitochondrial activity is reflected by the reduced ability to synthetize ATP as a source of energy [97]. In this scenario, data collected in the hippocampus of HFD mice are in line with recent studies on the topic, supporting that high fat consumption can affect mitochondria functionality, thus resulting in reduced respiratory capacity, decreased oxygen consumption, and reduced ATP production [70][98]. Indeed, we demonstrated in HFD mice, a significant reduction of both the expression levels and the activity of most respiratory chain complexes, especially Complex I, finally resulting in impaired ATP content in comparison to SD mice (

Figure 9).

4).

Proposed scenario of the altered mechanisms driven by HFD/IPA treatment. According to our data, nutrient overload results in defective insulin signaling both in HFD mice and IPA-treated SHSY-5Y cells, which translate into reduced glycolytic and mitochondrial metabolism. In turn, mitochondrial defects are responsible for impaired bioenergetic and increased ADP/ATP ratios that activate AMPK, a key GFAT1 inhibitor, leading to the reduced entrance of nutrients into the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP). GFAT1 inhibition, together with insulin resistance-driven nutrient deprivation, is responsible for the impairment of the HBP flux and the consequent reduction of the overall levels of O-GlcNAcylated proteins. The disruption of O-GlcNAc homeostasis is associated with altered OGT PTMs that could further exacerbate the efficiency of O-GlcNAc cycling. In addition, the reduction of Complex I-specific O-GlcNAcylation may represent a key aspect involved in exacerbating the alterations mitochondrial energetic profile.

Within this context, sustained alterations in O-GlcNAcylation either by pharmacological or genetic manipulation are known to reprogram mitochondrial function and may underlie reduced cellular respiration and ROS generation [103]. Furthermore, marked reduction of global O-GlcNAcylation strongly correlates with hampered bioenergetic function and disrupted mitochondrial network in AD models, while TMG-mediated restoration of overall O-GlcNAcylation has shown neuroprotective effects [36]. Mitochondria dysfunction is a hallmark of physiological and pathological brain ageing, which may prelude to impairment of synaptic activity and depletion of synapse. However, six-week HFD protocol did not affect the expression of pre- and postsynaptic proteins, suggesting that alteration of nutrient-dependent signaling and metabolic activity in neurons may anticipate the synaptic plasticity and structural plasticity deficits observed in experimental models of metabolic disease [104,105]. Intriguingly, we also highlighted that the impairment of the Complex I could be associated with the reduced O-GlcNAcylated levels of its subunit NDUFB8, as described elsewhere [46,47,72], thus describing a pivotal role for altered protein O-GlcNAcylation in triggering mitochondrial defects mediated by high-fat consumption (

Within this context, sustained alterations in O-GlcNAcylation either by pharmacological or genetic manipulation are known to reprogram mitochondrial function and may underlie reduced cellular respiration and ROS generation [99]. Furthermore, marked reduction of global O-GlcNAcylation strongly correlates with hampered bioenergetic function and disrupted mitochondrial network in AD models, while TMG-mediated restoration of overall O-GlcNAcylation has shown neuroprotective effects [36]. Mitochondria dysfunction is a hallmark of physiological and pathological brain ageing, which may prelude to impairment of synaptic activity and depletion of synapse. However, six-week HFD protocol did not affect the expression of pre- and postsynaptic proteins, suggesting that alteration of nutrient-dependent signaling and metabolic activity in neurons may anticipate the synaptic plasticity and structural plasticity deficits observed in experimental models of metabolic disease [100][101]. Intriguingly, we also highlighted that the impairment of the Complex I could be associated with the reduced O-GlcNAcylated levels of its subunit NDUFB8, as described elsewhere [46][47][102], thus describing a pivotal role for altered protein O-GlcNAcylation in triggering mitochondrial defects mediated by high-fat consumption (

Figure 9).

4).

In agreement with data collected in HFD, the administration of IPA for 24 h to SHSY-5Y neuroblastoma cells was able to induce insulin resistance, as previously observed in primary neurons [14], which translated into the lowered activity or readaptation of the glycolytic machinery and into the reduced mitochondrial respiratory potential in response to insulin stimulation. Intriguingly, as observed in HFD mice, IPA-induced insulin resistance and metabolic changes, after IPA treatment, were associated and self-sustained by total and Complex I-specific reduction of protein O-GlcNAcylation in neuronal-like cells, confirming the crucial role of such PTMs as sensor and mediator of energetic fluctuations.

Overall, our data suggest that a diet rich in fat is associated with insulin resistance and altered metabolism of the brain, which translates into reduced protein O-GlcNAcylation and mitochondrial dysfunction. In particular, HFD-related aberrant protein O-GlcNAcylation seems to have a double role in promoting neurodegeneration, by triggering the hyperphosphorylation of tau and by reducing complex I activity.

References

- Hammond, R.A.; Levine, R. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2010, 3, 285–295.

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S.H.; Hu, F.B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 88–98.

- Huang, R.; Tian, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, W.; Wang, S. Chronic hyperglycemia induces tau hyperphosphorylation by downregulating OGT-involved O-GlcNAcylation in vivo and in vitro. Brain Res. Bull. 2020, 156, 76–85.

- Zhao, L.; Feng, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, J. The regulatory roles of O-GlcNAcylation in mitochondrial homeostasis and metabolic syndrome. Free Radic. Res. 2016, 50, 1080–1088.

- Li, W.; Huang, E. An Update on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus as a Risk Factor for Dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 53, 393–402.

- Sposato, V.; Canu, N.; Fico, E.; Fusco, S.; Bolasco, G.; Ciotti, M.T.; Spinelli, M.; Mercanti, D.; Grassi, C.; Triaca, V.; et al. The Medial Septum is Insulin Resistant in the AD Presymptomatic Phase: Rescue by Nerve Growth Factor-Driven IRS1 Activation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 535–552.

- Di Domenico, F.; Barone, E.; Perluigi, M.; Butterfield, D.A. The Triangle of Death in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain: The Aberrant Cross-Talk among Energy Metabolism, Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Signaling, and Protein Homeostasis Revealed by Redox Proteomics. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 26, 364–387.

- Bedse, G.; Di Domenico, F.; Serviddio, G.; Cassano, T. Aberrant insulin signaling in Alzheimer’s disease: Current knowledge. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 204.

- Holscher, C. Insulin, incretins and other growth factors as potential novel treatments for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2014, 42, 593–599.

- Gerozissis, K. Brain insulin, energy and glucose homeostasis; genes, environment and metabolic pathologies. Eur. J. Pharm. 2008, 585, 38–49.

- Dubey, S.K.; Lakshmi, K.K.; Krishna, K.V.; Agrawal, M.; Singhvi, G.; Saha, R.N.; Saraf, S.; Saraf, S.; Shukla, R.; Alexander, A. Insulin mediated novel therapies for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci. 2020, 249, 117540.

- de Git, K.C.; Adan, R.A. Leptin resistance in diet-induced obesity: The role of hypothalamic inflammation. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 207–224.

- Petrov, D.; Pedros, I.; Artiach, G.; Sureda, F.X.; Barroso, E.; Pallas, M.; Casadesus, G.; Beas-Zarate, C.; Carro, E.; Ferrer, I.; et al. High-fat diet-induced deregulation of hippocampal insulin signaling and mitochondrial homeostasis deficiences contribute to Alzheimer disease pathology in rodents. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 1687–1699.

- Spinelli, M.; Fusco, S.; Mainardi, M.; Scala, F.; Natale, F.; Lapenta, R.; Mattera, A.; Rinaudo, M.; Li Puma, D.D.; Ripoli, C.; et al. Brain insulin resistance impairs hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory by increasing GluA1 palmitoylation through FoxO3a. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2009.

- Valladolid-Acebes, I.; Merino, B.; Principato, A.; Fole, A.; Barbas, C.; Lorenzo, M.P.; Garcia, A.; Del Olmo, N.; Ruiz-Gayo, M.; Cano, V. High-fat diets induce changes in hippocampal glutamate metabolism and neurotransmission. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 302, E396–E402.

- Boitard, C.; Cavaroc, A.; Sauvant, J.; Aubert, A.; Castanon, N.; Laye, S.; Ferreira, G. Impairment of hippocampal-dependent memory induced by juvenile high-fat diet intake is associated with enhanced hippocampal inflammation in rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 2014, 40, 9–17.

- Hardiville, S.; Hart, G.W. Nutrient regulation of signaling, transcription, and cell physiology by O-GlcNAcylation. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 208–213.

- Yang, X.; Qian, K. Protein O-GlcNAcylation: Emerging mechanisms and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 452–465.

- Joiner, C.M.; Li, H.; Jiang, J.; Walker, S. Structural characterization of the O-GlcNAc cycling enzymes: Insights into substrate recognition and catalytic mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 56, 97–106.

- Issad, T.; Kuo, M. O-GlcNAc modification of transcription factors, glucose sensing and glucotoxicity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 19, 380–389.

- Ruan, H.B.; Singh, J.P.; Li, M.D.; Wu, J.; Yang, X. Cracking the O-GlcNAc code in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 24, 301–309.

- Tramutola, A.; Sharma, N.; Barone, E.; Lanzillotta, C.; Castellani, A.; Iavarone, F.; Vincenzoni, F.; Castagnola, M.; Butterfield, D.A.; Gaetani, S.; et al. Proteomic identification of altered protein O-GlcNAcylation in a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 3309–3321.

- Di Domenico, F.; Owen, J.B.; Sultana, R.; Sowell, R.A.; Perluigi, M.; Cini, C.; Cai, J.; Pierce, W.M.; Butterfield, D.A. The wheat germ agglutinin-fractionated proteome of subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment hippocampus and inferior parietal lobule: Implications for disease pathogenesis and progression. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010, 88, 3566–3577.

- Di Domenico, F.; Lanzillotta, C.; Tramutola, A. Therapeutic potential of rescuing protein O-GlcNAcylation in tau-related pathologies. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2019, 19, 1–3.

- Bruehl, H.; Wolf, O.T.; Sweat, V.; Tirsi, A.; Richardson, S.; Convit, A. Modifiers of cognitive function and brain structure in middle-aged and elderly individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Brain Res. 2009, 1280, 186–194.

- Wang, X.; Zheng, W.; Xie, J.W.; Wang, T.; Wang, S.L.; Teng, W.P.; Wang, Z.Y. Insulin deficiency exacerbates cerebral amyloidosis and behavioral deficits in an Alzheimer transgenic mouse model. Mol. Neurodegener. 2010, 5, 46.

- Gong, C.X.; Liu, F.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K. Impaired brain glucose metabolism leads to Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration through a decrease in tau O-GlcNAcylation. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2006, 9, 1–12.

- Gong, C.X.; Liu, F.; Iqbal, K. O-GlcNAcylation: A regulator of tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Dement. 2016, 12, 1078–1089.

- Lefebvre, T.; Ferreira, S.; Dupont-Wallois, L.; Bussiere, T.; Dupire, M.J.; Delacourte, A.; Michalski, J.C.; Caillet-Boudin, M.L. Evidence of a balance between phosphorylation and O-GlcNAc glycosylation of Tau proteins--a role in nuclear localization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2003, 1619, 167–176.

- Liu, F.; Iqbal, K.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Hart, G.W.; Gong, C.X. O-GlcNAcylation regulates phosphorylation of tau: A mechanism involved in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA 2004, 101, 10804–10809.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Iqbal, K.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Gong, C.X. Decreased glucose transporters correlate to abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau in Alzheimer disease. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 359–364.

- Bhattacharya, A.; Limone, A.; Napolitano, F.; Cerchia, C.; Parisi, S.; Minopoli, G.; Montuori, N.; Lavecchia, A.; Sarnataro, D. APP Maturation and Intracellular Localization are Controlled by a Specific Inhibitor of 37/67 kDa Laminin-1 Receptor in Neuronal Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1738.

- Bhattacharya, A.; Izzo, A.; Mollo, N.; Napolitano, F.; Limone, A.; Margheri, F.; Mocali, A.; Minopoli, G.; Lo Bianco, A.; Di Maggio, F.; et al. Inhibition of 37/67kDa Laminin-1 Receptor Restores APP Maturation and Reduces Amyloid-beta in Human Skin Fibroblasts from Familial Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 232.

- Sarnataro, D. Attempt to Untangle the Prion-Like Misfolding Mechanism for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3081.

- Bubber, P.; Haroutunian, V.; Fisch, G.; Blass, J.P.; Gibson, G.E. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer brain: Mechanistic implications. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57, 695–703.

- Pinho, T.S.; Verde, D.M.; Correia, S.C.; Cardoso, S.M.; Moreira, P.I. O-GlcNAcylation and neuronal energy status: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 46, 32–41.

- Kamemura, K.; Hayes, B.K.; Comer, F.I.; Hart, G.W. Dynamic interplay between O-glycosylation and O-phosphorylation of nucleocytoplasmic proteins: Alternative glycosylation/phosphorylation of THR-58, a known mutational hot spot of c-Myc in lymphomas, is regulated by mitogens. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 19229–19235.

- Lanzillotta, C.; Di Domenico, F.; Perluigi, M.; Butterfield, D.A. Targeting Mitochondria in Alzheimer Disease: Rationale and Perspectives. CNS Drugs 2019, 33, 957–969.

- Dias, W.B.; Hart, G.W. O-GlcNAc modification in diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Biosyst. 2007, 3, 766–772.

- Kuljis, R.O.; Salkovic-Petrisic, M. Dementia, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and insulin resistance in the brain: Progress, dilemmas, new opportunities, and a hypothesis to tackle intersecting epidemics. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 25, 29–41.

- Szablewski, L. Glucose Transporters in Brain: In Health and in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 55, 1307–1320.

- Zhu, Y.; Shan, X.; Yuzwa, S.A.; Vocadlo, D.J. The emerging link between O-GlcNAc and Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 34472–34481.

- Tramutola, A.; Lanzillotta, C.; Barone, E.; Arena, A.; Zuliani, I.; Mosca, L.; Blarzino, C.; Butterfield, D.A.; Perluigi, M.; Di Domenico, F. Intranasal rapamycin ameliorates Alzheimer-like cognitive decline in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Transl. Neurodegener. 2018, 7, 28.

- Trapannone, R.; Mariappa, D.; Ferenbach, A.T.; van Aalten, D.M. Nucleocytoplasmic human O-GlcNAc transferase is sufficient for O-GlcNAcylation of mitochondrial proteins. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 1693–1702.

- Cao, W.; Cao, J.; Huang, J.; Yao, J.; Yan, G.; Xu, H.; Yang, P. Discovery and confirmation of O-GlcNAcylated proteins in rat liver mitochondria by combination of mass spectrometry and immunological methods. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76399.

- Ma, J.; Liu, T.; Wei, A.C.; Banerjee, P.; O’Rourke, B.; Hart, G.W. O-GlcNAcomic Profiling Identifies Widespread O-Linked beta-N-Acetylglucosamine Modification (O-GlcNAcylation) in Oxidative Phosphorylation System Regulating Cardiac Mitochondrial Function. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 29141–29153.

- Hu, Y.; Suarez, J.; Fricovsky, E.; Wang, H.; Scott, B.T.; Trauger, S.A.; Han, W.; Hu, Y.; Oyeleye, M.O.; Dillmann, W.H. Increased enzymatic O-GlcNAcylation of mitochondrial proteins impairs mitochondrial function in cardiac myocytes exposed to high glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 547–555.

- Tan, E.P.; Villar, M.T.; Lezi, E.; Lu, J.; Selfridge, J.E.; Artigues, A.; Swerdlow, R.H.; Slawson, C. Altering O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine cycling disrupts mitochondrial function. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 14719–14730.

- van der Laarse, S.A.M.; Leney, A.C.; Heck, A.J.R. Crosstalk between phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation: Friend or foe. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 3152–3167.

- Perluigi, M.; Barone, E.; Di Domenico, F.; Butterfield, D.A. Aberrant protein phosphorylation in Alzheimer disease brain disturbs pro-survival and cell death pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 1871–1882.

- Wang, Z.; Gucek, M.; Hart, G.W. Cross-talk between GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: Site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in response to globally elevated O-GlcNAc. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13793–13798.

- Heydemann, A. An Overview of Murine High Fat Diet as a Model for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 2902351.

- Whelan, S.A.; Dias, W.B.; Thiruneelakantapillai, L.; Lane, M.D.; Hart, G.W. Regulation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1)/AKT kinase-mediated insulin signaling by O-Linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 5204–5211.

- Arias, E.B.; Kim, J.; Cartee, G.D. Prolonged incubation in PUGNAc results in increased protein O-Linked glycosylation and insulin resistance in rat skeletal muscle. Diabetes 2004, 53, 921–930.

- Zuliani, I.; Lanzillotta, C.; Tramutola, A.; Francioso, A.; Pagnotta, S.; Barone, E.; Perluigi, M.; Di Domenico, F. The Dysregulation of OGT/OGA Cycle Mediates Tau and APP Neuropathology in Down Syndrome. Neurotherapeutics 2020.

- Ma, J.; Hart, G.W. Protein O-GlcNAcylation in diabetes and diabetic complications. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2013, 10, 365–380.

- Yang, X.; Ongusaha, P.P.; Miles, P.D.; Havstad, J.C.; Zhang, F.; So, W.V.; Kudlow, J.E.; Michell, R.H.; Olefsky, J.M.; Field, S.J.; et al. Phosphoinositide signalling links O-GlcNAc transferase to insulin resistance. Nature 2008, 451, 964–969.

- Cheung, W.D.; Hart, G.W. AMP-activated protein kinase and p38 MAPK activate O-GlcNAcylation of neuronal proteins during glucose deprivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 13009–13020.

- Whelan, S.A.; Lane, M.D.; Hart, G.W. Regulation of the O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine transferase by insulin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 21411–21417.

- Myslicki, J.P.; Belke, D.D.; Shearer, J. Role of O-GlcNAcylation in nutritional sensing, insulin resistance and in mediating the benefits of exercise. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 1205–1213.

- Hawkins, M.; Barzilai, N.; Liu, R.; Hu, M.; Chen, W.; Rossetti, L. Role of the glucosamine pathway in fat-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 1997, 99, 2173–2182.

- Scott, J.W.; Oakhill, J.S. The sweet side of AMPK signaling: Regulation of GFAT1. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1289–1292.

- Zibrova, D.; Vandermoere, F.; Goransson, O.; Peggie, M.; Marino, K.V.; Knierim, A.; Spengler, K.; Weigert, C.; Viollet, B.; Morrice, N.A.; et al. GFAT1 phosphorylation by AMPK promotes VEGF-induced angiogenesis. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 983–1001.

- Eguchi, S.; Oshiro, N.; Miyamoto, T.; Yoshino, K.; Okamoto, S.; Ono, T.; Kikkawa, U.; Yonezawa, K. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylates glutamine: Fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase 1 at Ser243 to modulate its enzymatic activity. Genes Cells 2009, 14, 179–189.

- Hebert, L.F., Jr.; Daniels, M.C.; Zhou, J.; Crook, E.D.; Turner, R.L.; Simmons, S.T.; Neidigh, J.L.; Zhu, J.S.; Baron, A.D.; McClain, D.A. Overexpression of glutamine: Fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase in transgenic mice leads to insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 98, 930–936.

- Barone, E.; Tramutola, A.; Triani, F.; Calcagnini, S.; Di Domenico, F.; Ripoli, C.; Gaetani, S.; Grassi, C.; Butterfield, D.A.; Cassano, T.; et al. Biliverdin Reductase-A Mediates the Beneficial Effects of Intranasal Insulin in Alzheimer Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 2922–2943.

- Barone, E.; Di Domenico, F.; Cassano, T.; Arena, A.; Tramutola, A.; Lavecchia, M.A.; Coccia, R.; Butterfield, D.A.; Perluigi, M. Impairment of biliverdin reductase-A promotes brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer disease: A new paradigm. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 91, 127–142.

- Contreras, A.; Del Rio, D.; Martinez, A.; Gil, C.; Morales, L.; Ruiz-Gayo, M.; Del Olmo, N. Inhibition of hippocampal long-term potentiation by high-fat diets: Is it related to an effect of palmitic acid involving glycogen synthase kinase-3? Neuroreport 2017, 28, 354–359.

- Mainardi, M.; Spinelli, M.; Scala, F.; Mattera, A.; Fusco, S.; D’Ascenzo, M.; Grassi, C. Loss of Leptin-Induced Modulation of Hippocampal Synaptic Trasmission and Signal Transduction in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 225.

- Cavaliere, G.; Trinchese, G.; Penna, E.; Cimmino, F.; Pirozzi, C.; Lama, A.; Annunziata, C.; Catapano, A.; Mattace Raso, G.; Meli, R.; et al. High-Fat Diet Induces Neuroinflammation and Mitochondrial Impairment in Mice Cerebral Cortex and Synaptic Fraction. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 509.

- Alzoubi, K.H.; Mayyas, F.A.; Mahafzah, R.; Khabour, O.F. Melatonin prevents memory impairment induced by high-fat diet: Role of oxidative stress. Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 336, 93–98.

- Hart, G.W. Nutrient regulation of signaling and transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 2211–2231.

- Harwood, K.R.; Hanover, J.A. Nutrient-driven O-GlcNAc cycling—think globally but act locally. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 1857–1867.

- Cordner, Z.A.; Tamashiro, K.L. Effects of high-fat diet exposure on learning & memory. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152, 363–371.

- Greenwood, C.E.; Winocur, G. High-fat diets, insulin resistance and declining cognitive function. Neurobiol. Aging 2005, 26 (Suppl. 1), 42–45.

- Ducheix, S.; Magre, J.; Cariou, B.; Prieur, X. Chronic O-GlcNAcylation and Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: The Bitterness of Glucose. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 642.

- Park, K.; Saudek, C.D.; Hart, G.W. Increased expression of beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase in erythrocytes from individuals with pre-diabetes and diabetes. Diabetes 2010, 59, 1845–1850.

- McLean, F.H.; Grant, C.; Morris, A.C.; Horgan, G.W.; Polanski, A.J.; Allan, K.; Campbell, F.M.; Langston, R.F.; Williams, L.M. Rapid and reversible impairment of episodic memory by a high-fat diet in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11976.

- Davidson, T.L.; Monnot, A.; Neal, A.U.; Martin, A.A.; Horton, J.J.; Zheng, W. The effects of a high-energy diet on hippocampal-dependent discrimination performance and blood-brain barrier integrity differ for diet-induced obese and diet-resistant rats. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 107, 26–33.

- Butterfield, D.A.; Di Domenico, F.; Barone, E. Elevated risk of type 2 diabetes for development of Alzheimer disease: A key role for oxidative stress in brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1693–1706.

- Koekkoek, P.S.; Kappelle, L.J.; van den Berg, E.; Rutten, G.E.; Biessels, G.J. Cognitive function in patients with diabetes mellitus: Guidance for daily care. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 329–340.

- Liu, F.; Shi, J.; Tanimukai, H.; Gu, J.; Gu, J.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K.; Gong, C.X. Reduced O-GlcNAcylation links lower brain glucose metabolism and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2009, 132, 1820–1832.

- Park, J.; Lai, M.K.P.; Arumugam, T.V.; Jo, D.G. O-GlcNAcylation as a Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuromolecular. Med. 2020, 22, 171–193.

- Zhu, Y.; Shan, X.; Safarpour, F.; Erro Go, N.; Li, N.; Shan, A.; Huang, M.C.; Deen, M.; Holicek, V.; Ashmus, R.; et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of O-GlcNAcase Enhances Autophagy in Brain through an mTOR-Independent Pathway. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 1366–1379.

- Gatta, E.; Lefebvre, T.; Gaetani, S.; dos Santos, M.; Marrocco, J.; Mir, A.M.; Cassano, T.; Maccari, S.; Nicoletti, F.; Mairesse, J. Evidence for an imbalance between tau O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation in the hippocampus of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharm. Res. 2016, 105, 186–197.

- Calvo-Ochoa, E.; Hernandez-Ortega, K.; Ferrera, P.; Morimoto, S.; Arias, C. Short-term high-fat-and-fructose feeding produces insulin signaling alterations accompanied by neurite and synaptic reduction and astroglial activation in the rat hippocampus. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2014, 34, 1001–1008.

- Woods, Y.L.; Cohen, P.; Becker, W.; Jakes, R.; Goedert, M.; Wang, X.; Proud, C.G. The kinase DYRK phosphorylates protein-synthesis initiation factor eIF2Bepsilon at Ser539 and the microtubule-associated protein tau at Thr212: Potential role for DYRK as a glycogen synthase kinase 3-priming kinase. Biochem. J. 2001, 355, 609–615.

- Yuzwa, S.A.; Yadav, A.K.; Skorobogatko, Y.; Clark, T.; Vosseller, K.; Vocadlo, D.J. Mapping O-GlcNAc modification sites on tau and generation of a site-specific O-GlcNAc tau antibody. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 857–868.

- Jacobsen, K.T.; Iverfeldt, K. O-GlcNAcylation increases non-amyloidogenic processing of the amyloid-beta precursor protein (APP). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 404, 882–886.

- Yuzwa, S.A.; Shan, X.; Jones, B.A.; Zhao, G.; Woodward, M.L.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; McEachern, E.J.; Silverman, M.A.; Watson, N.V.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of O-GlcNAcase (OGA) prevents cognitive decline and amyloid plaque formation in bigenic tau/APP mutant mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 2014, 9, 42.

- Kothari, V.; Luo, Y.; Tornabene, T.; O’Neill, A.M.; Greene, M.W.; Geetha, T.; Babu, J.R. High fat diet induces brain insulin resistance and cognitive impairment in mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 499–508.

- Arnold, S.E.; Lucki, I.; Brookshire, B.R.; Carlson, G.C.; Browne, C.A.; Kazi, H.; Bang, S.; Choi, B.R.; Chen, Y.; McMullen, M.F.; et al. High fat diet produces brain insulin resistance, synaptodendritic abnormalities and altered behavior in mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 67, 79–87.

- Park, S.Y.; Ryu, J.; Lee, W. O-GlcNAc modification on IRS-1 and Akt2 by PUGNAc inhibits their phosphorylation and induces insulin resistance in rat primary adipocytes. Exp. Mol. Med. 2005, 37, 220–229.

- Bullen, J.W.; Balsbaugh, J.L.; Chanda, D.; Shabanowitz, J.; Hunt, D.F.; Neumann, D.; Hart, G.W. Cross-talk between two essential nutrient-sensitive enzymes: O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 10592–10606.

- Gelinas, R.; Mailleux, F.; Dontaine, J.; Bultot, L.; Demeulder, B.; Ginion, A.; Daskalopoulos, E.P.; Esfahani, H.; Dubois-Deruy, E.; Lauzier, B.; et al. AMPK activation counteracts cardiac hypertrophy by reducing O-GlcNAcylation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 374.

- Kang, J.G.; Park, S.Y.; Ji, S.; Jang, I.; Park, S.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.M.; Yook, J.I.; Park, Y.I.; Roth, J.; et al. O-GlcNAc protein modification in cancer cells increases in response to glucose deprivation through glycogen degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 34777–34784.

- Chen, D.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, M.; Gao, L. A high-fat diet impairs mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial dynamics, and the respiratory chain complex in rat myocardial tissues. J. Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 9602.

- Miotto, P.M.; LeBlanc, P.J.; Holloway, G.P. High-Fat Diet Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction as a Result of Impaired ADP Sensitivity. Diabetes 2018, 67, 2199–2205.

- Tan, E.P.; McGreal, S.R.; Graw, S.; Tessman, R.; Koppel, S.J.; Dhakal, P.; Zhang, Z.; Machacek, M.; Zachara, N.E.; Koestler, D.C.; et al. Sustained O-GlcNAcylation reprograms mitochondrial function to regulate energy metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 14940–14962.

- Carvalho, C.; Santos, M.S.; Oliveira, C.R.; Moreira, P.I. Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes-related alterations in brain mitochondria, autophagy and synaptic markers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 1665–1675.

- Wang, J.Q.; Yin, J.; Song, Y.F.; Zhang, L.; Ren, Y.X.; Wang, D.G.; Gao, L.P.; Jing, Y.H. Brain aging and AD-like pathology in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Diabetes Res. 2014, 2014, 796840.

- Wright, J.N.; Benavides, G.A.; Johnson, M.S.; Wani, W.; Ouyang, X.; Zou, L.; Collins, H.E.; Zhang, J.; Darley-Usmar, V.; Chatham, J.C. Acute increases in O-GlcNAc indirectly impair mitochondrial bioenergetics through dysregulation of LonP1-mediated mitochondrial protein complex turnover. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019, 316, C862–C875.