Lithium (Li+) salt is widely used as a therapeutic agent for treating neurological and psychiatric disorders. Despite its therapeutic effects on neurological and psychiatric disorders, it can also disturb the neuroendocrine axis in patients under lithium therapy. The hypothalamic area is involved in the physiological control of anterior pituitary hormones and the regulation of the neuroendocrine system. Li+ can modulate neuronal properties and a neurotransmitter system in various neuronal populations. However, the effect of Li+ on hypothalamic neuronal excitability has not been fully understood yet.

- lithium

- hypothalamic preoptic area neurons

- GABAergic neurotransmission

- patch-clamp

- neuroendocrine axis

1. Introduction

As detailed in our recent publication (https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22083908): Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is well known to be a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS) [1]. Excitation and inhibition of neuronal activities in the CNS are balanced by GABAergic transmission, whose impairment can result in various CNS disorders [2][3]. Various physiological and pathological conditions continuously modulate the strength and polarity of GABAergic transmission in the CNS [4]. The hypothalamic area of the CNS contains GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons and their receptors that regulate various hypothalamic functions such as the release of neurohormones, control circadian activities [5] . Additionally, some hypothalamus areas receive GABAergic and glycinergic innervations from other brain areas [6][7][8].

In the hypothalamic preoptic area (hPOA), GABA and glutamate mediate most of the fast postsynaptic potentials/events, indicating that neuronal communications in the hypothalamic area are due to amino acid neurotransmitters [9]. GABA in the hypothalamic area exerts multiple effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary system. It is involved in the physiological control of anterior pituitary hormones [10] , and regulation of the neuroendocrine system [6]. The hPOA is critically involved in several homeostatic processes such as sleep, reproduction, osmolality, body temperature, and behavior process as most brain regions have interconnections to the hPOA [11].

Lithium-ion (Li+) is known to exhibit a therapeutic effect in the treatment of some neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s diseases, Alzheimer’s diseases, and bipolar disorder [12][13]. Neurotransmitters such as GABA, glutamate, dopamine, glycine, and acetylcholine are modulated by lithium [13]. It has been reported that Li+ suppresses dopamine and glutamate transmissions but increases GABA neurotransmission at the neuronal level [14]. For example, granule cells (GCs) in the hippocampal dentate gyrus show increased GABAergic synaptic inputs to GCs by lithium [15]. Besides, Li+ can act on the second-messenger system at the intracellular and molecular level, thus, regulating neurotransmission [14].

Both in vivo and in vitro studies have suggested that Li+ can alter the release of several hormones such as prolactin, growth hormone [16] , corticotropin-releasing hormone [17] , arginine vasopressin [18] , and opioid peptides like β-endorphin, dynorphin, and met-enkephalin from the hypothalamus [19]. Furthermore, Li+ can suppress the secretion of gonadotropins and gonadal hormones [20], decrease testosterone levels in male rats, and increase estrogen levels in female rats [21]. Several clinical cases have reported that Li+ can impact hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) [22][23] , hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) [24], and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axes [25]. However, the effect of Li+ on hypothalamic neuronal excitability and the precise action mechanism involved in such an effect have not been fully understood yet. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate Li+ action on hypothalamic neurons using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique.

2. LDithium and hPOA Neurscussions

Results of this study showed that Li+ increased GABAergic synaptic activities in hypothalamic preoptic area neurons by action potential independent presynaptic mechanisms as TTX (a voltage-gated Na+ channel blocker) did not affect the frequency of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) increased by Li+. Besides, Li+ perfusion induced inward current for the majority of hPOA neurons. These findings are consistent with previous studies, showing that Li+ administration can alter the resting potential [26][27] , and enhance GABAergic activities [15].

In the hypothalamic preoptic area, about 70 neuronal populations have been identified with inhibitory neurons being the most abundant [28]. GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmissions are the major inputs for neuronal regulation in the hypothalamus [29][30]. Besides, this region has interconnections to various brain areas [11] and receives glycinergic innervation [7][8]. GABA and glycine are major inhibitory transmitters whereas glutamate is the major excitatory transmitter in CNS. Electrophysiological experiments have revealed both excitatory and inhibitory effects of Li+ on neuronal excitability [15][26][31].

In electrophysiology, complete or partial replacement of Na+ by Li+ in the external medium could modulate neuronal properties and a neurotransmitter system. For example, Li+ induced depolarization and altered the frequency and shape of the action potential in mitral cells [26] . Similarly, both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission were enhanced by Li+ perfusion [15][32][33]. Furthermore, chronic lithium administration resulted in a significant change of the brain neurotransmitter system of selected brain regions [34]. At the neuronal level, Li+ exhibited both pre-synaptic and post-synaptic action to modulate neurotransmission mediated by dopamine, GABA, glutamate, and serotonin [14][35] . Li+ induced a change in the GABAergic system and GABA receptors have been well documented in various areas of CNS, such as corpus striatum [34], prefrontal cortex [36] , hypothalamus [34][37], and dentate gyrus [15] .

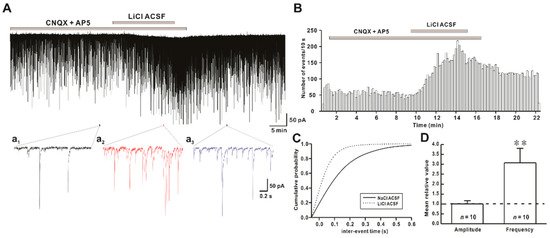

Figure 1. Effect of Li+ (126 mM) on spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) on hypothalamic preoptic area (hPOA) neurons. (A) A representative current trace of sIPSCs recorded in the presence of Na+ and Li+ artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) on hPOA neurons at a holding potential of −60 mV. (a1–a3), sections of the current trace in Figure 1A show sIPSCs before, during, and after perfusion of Li+ at 2 s intervals, respectively. (B) A spike frequency histogram (bin size 10 s) of current traces in Figure 1A. (C) A cumulative probability plot of sIPSCs inter-event interval (IEI) in the presence of Na+ (solid line) and Li+ (dotted line). Note that the cumulative probability curve was left-shifted by Li+, indicating the increase of sIPSCs frequency (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p < 0.05). (D) Mean relative amplitude and frequency of sIPSCs in LiCl ACSF compared to NaCl ACSF (** p < 0.01 by a paired t-test).

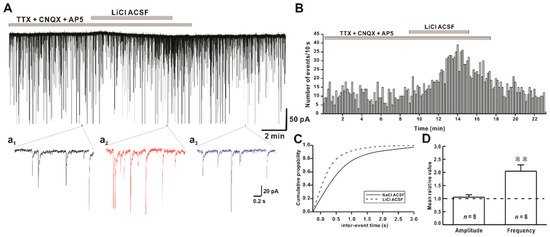

Findings of the present study suggest that the replacement of Na+ by Li+ in ACSF could rapidly increase the frequency of synaptic activities without altering their amplitudes (Figure 1). In addition, there was no significant difference between the increased ratio of sIPSCs and mIPSCs frequency induced by Li+, indicating that Li+ enhanced the action potential-independent presynaptic mechanism mediated GABAergic synaptic events (Figure 2). However, Lee et al. have observed that exposure to Li+ (25 mM) could enhance GABAergic synaptic activities by AP-dependent and AP-independent presynaptic mechanisms in hippocampal slices [15]. Our results also revealed that concentration-dependent replacement of Na+ by Li+ in ACSF increased frequencies of GABAergic mIPSCs without affecting their amplitudes.

Figure 2. Effect of Li+ on miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) on hPOA neurons. (A) A representative current trace of mIPSCs recorded in the presence of Na+ and Li+ ACSF on hPOA neurons at a holding potential of −60 mV. (a1–a3), sections of the current trace in Figure 2A show mIPSCs before, during, and after perfusion of Li+ at 2-s intervals, respectively. (B) A spike frequency histogram of the current trace in Figure 2A. (C) A cumulative probability plot of mIPSCs inter-event interval (IEI) in the presence of Na+ (solid line) and Li+ (dotted line). Note that the cumulative probability curve was left-shifted by Li+, indicating the increase of mIPSCs frequency (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p < 0.05). (D) Mean relative amplitude and frequency of mIPSCs in LiCl ACSF compared to NaCl ACSF (** p < 0.01 by paired t-test).

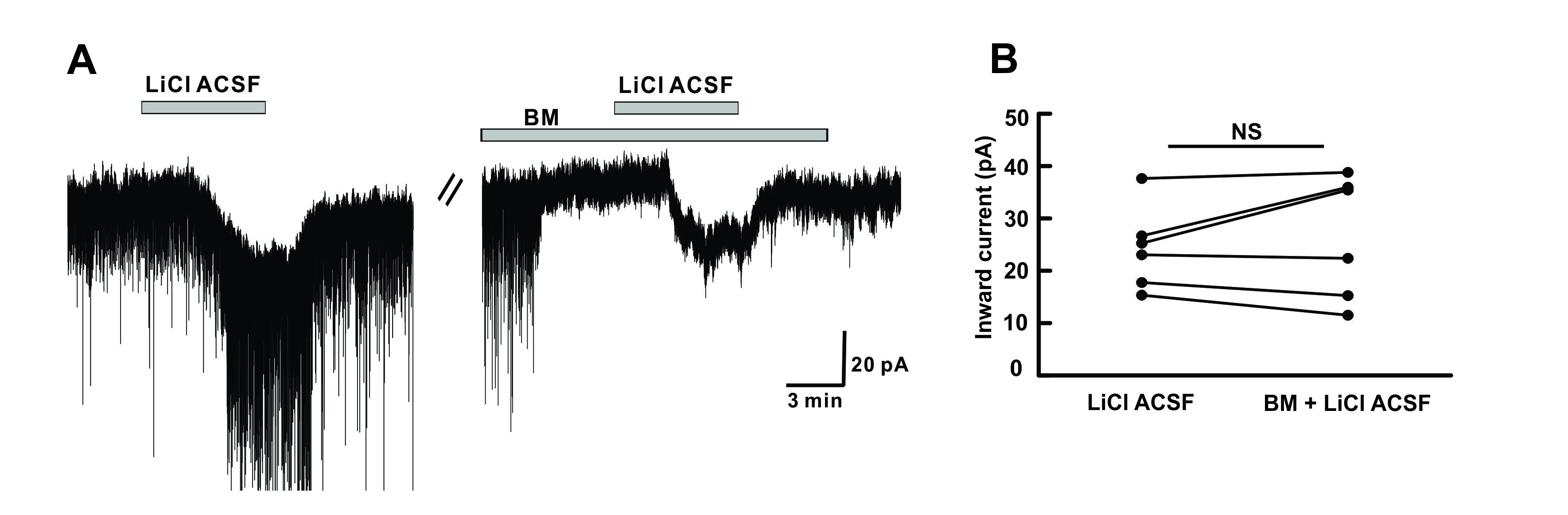

In addition to the presynaptic effect, the postsynaptic effect of Li+ on neuronal regulation has been reported in various neuronal groups [26][38][39]. Replacement of Na+ with Li+ can induce depolarization in cortical neurons[26] , giant neurons [38] , CA1 neurons [40] , spinal motoneurons, and olfactory cortex [39] . Similarly, we observed an inward current when LiCl ACSF perfusion was performed. Li+ induced non-desensitizing repeatable inward currents. Such responses were preserved in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX, a voltage-gated Na+ channel blocker) and blocker for amino acid receptors (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Li+ acts on postsynaptic hPOA neurons. (A) A representative current trace showing inward currents induced upon perfusion of LiCl ACSF. Li+ induced inward current persisted in the presence of BM (blocking mixture), including TTX (Na+ channel blocker), picrotoxin (GABAA receptor blocker), strychnine (glycine receptor blocker), CNQX (non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist), and AP5 (NMDA receptor antagonist). (B) The before and after plot shows no significant difference in the mean inward current between Li+ alone and Li+ in the presence of blocking mixture (n = 6, p > 0.05 by the paired t-test). NS, not significant.

Figure 3. Li+ acts on postsynaptic hPOA neurons. (A) A representative current trace showing inward currents induced upon perfusion of LiCl ACSF. Li+ induced inward current persisted in the presence of BM (blocking mixture), including TTX (Na+ channel blocker), picrotoxin (GABAA receptor blocker), strychnine (glycine receptor blocker), CNQX (non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist), and AP5 (NMDA receptor antagonist). (B) The before and after plot shows no significant difference in the mean inward current between Li+ alone and Li+ in the presence of blocking mixture (n = 6, p > 0.05 by the paired t-test). NS, not significant.

Previous findings have suggested that Li+ can replace Na+ ions and pass through neuronal membranes along Na+ channels [26][38][41]. In addition, Li+ can interact with electrogenic Na+/K+ pumps as three action sites for Li+ interaction has been identified [39] . To induce membrane depolarization, Li+ might suppress the activity of an electrogenic Na+ pump, reduce the intracellular K+ concentration, and increase the release of an excitatory transmitter [39][42][43] . Grafe et.al have demonstrated that Li+ can induce a shift of the K+ equilibrium potential responsible for membrane depolarization of neurons [39] . In the present study, we observed that Li+ directly acted on hPOA neurons independent of voltage-gated Na+ channels, GABAA, glycine, or ionotropic glutamate receptors. However, we could not elucidate the complete mechanism responsible for the induced inward current.

Neurotransmission disturbances have been reported in several neurological disorders [44][45] , and lithium salt is widely used as a therapeutic agent for treating neurological and psychiatric disorders [46][47]. The therapeutic mechanism of Li+ involves its neuroprotective effect, neurotropic effect, and neuronal plasticity [13][48]. Lithium exhibits a neuroprotective effect by modulating glutamatergic transmission and inhibiting N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated calcium influx induced excitotoxicity [49][50]. Besides, Li+ can regulate synaptic plasticity by suppressing α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) glutamate receptor trafficking [51]. Despite its therapeutic effects on neurological and psychiatric disorders, it can disturb the neuroendocrine axis, mainly in hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients under lithium therapy [52][53] . Besides, oral lithium administration can result in Li+ accumulation in central neuroendocrine tissues, such as the hypothalamus and pituitary gland [54] . Furthermore, our electrophysiological data showed an increase in GABAergic neurotransmission across the hypothalamic preoptic area upon lithium exposure. This indicates that Li+ treatment might directly affect the hypothalamic region of the brain and regulate the release of various neurohormones involved in synchronizing the neuroendocrine axis. However, the mechanism behind the induced inward current on hPOA neurons upon Li+ perfusion warrants further investigation.

It has been reported that lithium and anti-epileptic drugs showed side effects on the endocrine system. Alteration in the endocrine system might lead to endocrine complications and related health problems. These complications may arise from altered neurotransmission in the hypothalamus. Using the electrophysiology approach, we showed that GABAergic activity was increased across hypothalamic neurons upon Li+ exposure, explaining the cause for the disruption in the neuroendocrine axis in patients receiving lithium therapy.

References

- Watanabe, M.; Maemura, K.; Kanbara, K.; Tamayama, T.; Hayasaki, H. GABA and GABA receptors in the central nervous system and other organs. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2002, 231, 1–47.

- Kirmse, K.; Holthoff, K. Functions of GABAergic transmission in the immature brain. e-Neuroforum 2017, 23, 27–33.

- Ramamoorthi, K.; Lin, Y. The contribution of GABAergic dysfunction to neurodevelopmental disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 452–462.

- Deidda, G.; Bozarth, I.F.; Cancedda, L. Modulation of GABAergic transmission in development and neurodevelopmental disorders: Investigating physiology and pathology to gain therapeutic perspectives. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8,119.

- Belousov, A.B.; O'Hara, B.F.; Denisova, J.V. Acetylcholine becomes the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the hypothalamus in vitro in the absence of glutamate excitation. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 2015–2027.

- Vincent, S.R.; Hökfelt, T.; Wu, J.Y. GABA neuron systems in hypothalamus and the pituitary gland. Neuroendocrinology 1982, 34, 117–125.

- Rampon, C.; Luppi, P.H.; Fort, P.; Peyron, C.; Jouvet, M. Distribution of glycine-immunoreactive cell bodies and fibers in the rat brain. Neuroscience 1996, 75, 737–755.

- Zeilhofer, H.U.; Studler, B.; Arabadzisz, D.; Schweizer, C.; Ahmadi, S.; Layh, B.; Bösl, M.R.; Fritschy, J.M. Glycinergic neurons expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein in bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 482, 123–141.

- Hoffman, N.W.; Wuarin, J.P.; Dudek, F.E. Whole-cell recordings of spontaneous synaptic currents in medial preoptic neurons from rat hypothalamic slices: Mediation by amino acid neurotransmitters. Brain Res. 1994, 660, 349–352.

- McCann, S.M.; Vijayan, E.; Negro-Vilar, A.; Mizunuma, H.; Mangat, H. Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), a modulator of anterior pituitary hormone secretion by hypothalamic and pituitary action. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1984, 9, 97–106.

- Yu, S.; François, M.; Huesing, C.; Münzberg, H. The hypothalamic preoptic area and body weight control. Neuroendocrinology 2017, 106, 187–194.

- Mikosha, A.S.; Kovzun, O.I.; Tronko, M.D. Biological effects of lithium–fundamental and medical aspects. Ukr. Biochem. J. 2017, 89, 5–16.

- Won, E.; Kim, Y.K. An oldie but goodie: Lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder through neuroprotective and neurotrophic mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2679.

- Malhi, G.S.; Tanious, M.; Das, P.; Coulston, C.M.; Berk, M. Potential mechanisms of action of lithium in bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs 2013, 27, 135–153.

- Lee, S.H.; Sohn, J.W.; Ahn, S.C.; Park, W.S.; Ho, W.K. Li+ enhances GABAergic inputs to granule cells in the rat hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neuropharmacology 2004, 46, 638–646.

- Smythe, G.A.; Brandstater, J.F.; Lazarus, L. Acute effects of lithium on central dopamine and serotonin activity reflected by inhibition of prolactin and growth hormone secretion in the rat. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 1979, 32, 329–334.

- Bschor, T.; Ritter, D.; Winkelmann, P.; Erbe, S.; Uhr, M.; Ising, M.; Lewitzka, U. Lithium monotherapy increases ACTH and cortisol response in the DEX/CRH test in unipolar depressed subjects. A study with 30 treatment-naive patients. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27613.

- Anai, H.; Ueta, Y.; Serino, R.; Nomura, M.; Kabashima, N.; Shibuya, I.; Takasugi, M.; Nakashima, Y.; Yamashita, H. Upregulation of the expression of vasopressin gene in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the lithium-induced diabetes insipidus rat. Brain Res. 1997, 772, 161–166.

- Burns, G.; Herz, A.; Nikolarakis, K. Stimulation of hypothalamic opioid peptide release by lithium is mediated by opioid autoreceptors: Evidence from a combined in vitro, ex vivo study. Neuroscience 1990, 36, 691–697.

- Sheikha, S.H.; LeGate, L.S.; Banerji, T.K. Lithium suppresses ovariectomy-induced surges in plasma gonadotropins in rats. Life Sci. 1989, 44, 1363–1369.

- Allagui, M.; Hfaiedh, N.; Croute, F.; Guermazi, F.; Vincent, C.; Soleilhavoup, J.; El, A.F. Side effects of low serum lithium concentrations on renal, thyroid, and sexual functions in male and female rats. C. R. Biol. 2005, 328, 900–911.

- Bschor, T.; Adli, M.; Baethge, C.; Eichmann, U.; Ising, M.; Uhr, M.; Modell, S.; Künzel, H.; Müller-Oerlinghausen, B.; Bauer, M. Lithium augmentation increases the ACTH and cortisol response in the combined DEX/CRH test in unipolar major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002, 27, 470–478.

- Sugawara, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Hattori, T.; Takao, T.; Suemaru, S.; Ota, Z. Effects of lithium on the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocrinol. Jpn. 1988, 35, 655–663.

- Lombardi, G.; Panza, N.; Biondi, B.; Di Lorenzo, L.; Lupoli, G.; Muscettola, G.; Carella, C.; Bellastella, A. Effects of lithium treatment on hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis: A longitudinal study. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 1993, 16, 259–263.

- Kusalic, M.; Engelsmann, F. Effect of lithium maintenance treatment on hypothalamic pituitary gonadal axis in bipolar men. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 1996, 21, 181–186.

- Butler-Munro, C.; Coddington, E.J.; Shirley, C.H.; Heyward, P.M. Lithium modulates cortical excitability in vitro. Brain Res. 2010, 1352, 50–60.

- Wu, M.; Zaborszky, L.; Hajszan, T.; Van Den Pol, A.N.; Alreja, M. Hypocretin/orexin innervation and excitation of identified septohippocampal cholinergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 3527–3536.

- Moffitt, J.R.; Bambah-Mukku, D.; Eichhorn, S.W.; Vaughn, E.; Shekhar, K.; Perez, J.D.; Rubinstein, N.D.; Hao, J.; Regev, A.; Dulac, C. Molecular, spatial, and functional single-cell profiling of the hypothalamic preoptic region. Science 2018, 362, 641.

- Decavel, C.; Van Den Pol, A.N. GABA: A dominant neurotransmitter in the hypothalamus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990, 302, 1019–1037.

- Van Den Pol, A.N.; Trombley, P.Q. Glutamate neurons in hypothalamus regulate excitatory transmission. J. Neurosci. 1993, 13, 2829–2836.

- Lacaille, J.C.; Cloutier, S.; Reader, T.A. Lithium reduced synaptic transmisson and increased neuronal excitability without altering endogenous serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine in rat hippocampal slices in vitro. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1992, 3, 397–412.

- Higashitani, Y.; Kudo, Y.; Ogura, A.; Kato, H. Acute effects of lithium on synaptic transmission in rat hippocampus studied in vitro. Biol. Psychiatry 1990, 27, 174–182.

- Valentı́n, A.; Garcı́a-Seoane, J.J.; Colino, A. Lithium enhances synaptic transmission in neonatal rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 1997, 78, 385–391.

- Maggi, A.; Enna, S. Regional alterations in rat brain neurotransmitter systems following chronic lithium treatment. J. Neurochem. 1980, 34, 888–892.

- Tanimoto, K.; Maeda, K.; Terada, T. Inhibitory effect of lithium on neuroleptic and serotonin receptors in rat brain. Brain Res. 1983, 265, 148–151.

- Antonelli, T.; Ferioli, V.; Lo Gallo, G.; Tomasini, M.C.; Fernandez, M.; O'Connor, W.T.; Glennon, J.C.; Tanganelli, S.; Ferraro, L. Differential effects of acute and short‐term lithium administration on dialysate glutamate and GABA levels in the frontal cortex of the conscious rat. Synapse 2000, 38, 355–362.

- Gottesfeld, Z.; Ebstein, B.S.; Samuel, D. Effect of lithium on concentrations of glutamate and GABA levels in amygdala and hypothalamus of rat. Nat. New Biol. 1971, 234, 124–125.

- Akoev, G.; Sizaya, N. Influence of lithium ions on the electrical activity of nerve cells of the leech. Neurophysiology 1970, 2, 484–489.

- Grafe, P.; Reddy, M.; Emmert, H.; Ten Bruggencate, G. Effects of lithium on electrical activity and potassium ion distribution in the vertebrate central nervous system. Brain Res. 1983, 279, 65–76.

- Liu, X.; Leung, L.S. Sodium-activated potassium conductance participates in the depolarizing afterpotential following a single action potential in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Brain Res. 2004, 1023, 185–192.

- Janka, Z.; Jones, D. Lithium entry into neural cells via sodium channels: A morphometric approach. Neuroscience 1982, 7, 2849–2857.

- Obara, S.; Grundfest, H. Effects of lithium on different membrane components of crayfish stretch receptor neurons. J. Gen. Physiol. 1968, 51, 635–654.

- Giacobini, E.; Hovmark, S.; Stepita‐Klauco, M. Studies on the Mechanism of Action of Lithium Ions: II. Potassium Sensitive Influx of Lithium Ions into the Crayfish Stretch Receptor Neuron Determined by Microflamephotometry. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1970, 80, 528–532.

- Leite, J.A.; Orellana, A.M.M.; Kinoshita, P.F.; de Mello, N.P.; Scavone, C.; Kawamoto, E.M. Neuroinflammation and Neurotransmission Mechanisms Involved in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. In Mechanisms of Neuroinflammation; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017.

- Sheffler, Z.M.; Reddy, V.; Pillarisetty, L.S. Physiology, Neurotransmitters; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020.

- Forlenza, O.V.; De-Paula, V.J.R.; Diniz, B.S.O. Neuroprotective effects of lithium: Implications for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and related neurodegenerative disorders. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 443–450.

- Maletzky, B.M.; Shore, J.H. Lithium treatment for psychiatric disorders. West. J. Med. 1978, 128, 488–498.

- Segal, J. Lithium-an update on the mechanisms of action. Part two: Neural effects and neuroanatomical substrate. Afr. J. Psychiatry 2004, 7, 18–24.

- Shibuya-Tayoshi, S.; Tayoshi, S.Y.; Sumitani, S.; Ueno, S.; Harada, M.; Ohmori, T. Lithium effects on brain glutamatergic and GABAergic systems of healthy volunteers as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 249–256.

- Nonaka, S.; Hough, C.J.; Chuang, D.M. Chronic lithium treatment robustly protects neurons in the central nervous system against excitotoxicity by inhibiting N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated calcium influx. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2642–2647.

- Du, J.; Gray, N.A.; Falke, C.A.; Chen, W.; Yuan, P.; Szabo, S.T.; Einat, H.; Manji, H.K. Modulation of synaptic plasticity by antimanic agents: The role of AMPA glutamate receptor subunit 1 synaptic expression. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 6578–6589.

- Giusti, C.F.; Amorim, S.R.; Guerra, R.A.; Portes, E.S. Endocrine disturbances related to the use of lithium. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2012, 56, 153–158.

- Filippa, V.P.; Mohamed, F.H. Lithium Therapy Effects on the Reproductive System. In Psychiatry and Neuroscience Update; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 187–200.

- Pfeifer, W.D.; Davis, L.; Van der Velde, C.D. Lithium accumulation in some endocrine tissues. Acta Biol. Med. Ger. 1976. 35, 1519–1523.