Vitamin B6 is an essential nutrient for the human health. It is involved in more that 150 metabolic reactions which regulate the metabolism of glucose, lipids, amino acids, DNA, and neurotransmitters. In addition, vitamin B6 is an antioxidant molecule able to counteracting the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and advanced glycation end-products (AGEs). Epidemiological and experimental studies indicated the reduced levels of vitamin B6 can cause diabetes. In contrast other studies show that diabetes decreases vitamin B6 levels. Thus these findings lead to envisage the existence of a vicious circle at the basis of the relationship between vitamin B6 and diabetes. This entry reports the main evidence concerning the role of vitamin B6 in diabetes and examine the underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms.

- vitamin B6

- diabetes

- tryptophan metabolism

1. Vitamin B6 and Diabetes

By considering the plethora of reactions in which vitamin B6 is involved, it is not surprising that its deficiency has been implicated in several clinically relevant diseases, including autism, schizophrenia, Alzheimer, Parkinson, epilepsy, Down’s syndrome, diabetes, and cancer; however, the underlying mechanisms remain unknown in most cases [1][2][3].

Diabetes mellitus (DM) represents a global health problem, touching more than 400 million people and consists of a group of metabolic disorders characterized by persistent hyperglycemia arising from impaired insulin secretion, insulin action, or both [4]. DM is a multifactorial disease caused by the concerted action of genetic and environmental factors, and on the basis of its etiology, it can be classified into three major types—type1 (T1D), type2 (T2D), and gestational diabetes (GDM). T1D is an autoimmune disorder that leads to the destruction of pancreatic beta-cells and accounts for only 5–10% of all diabetes. T2D, the more frequent form (90–95%), is mainly caused by insulin resistance consisting of a diminished tissue response to insulin that leads glucose to accumulate in blood. Consequently, the rate of insulin secretion increases to meet the body’s needs, but this overload, in the long-term, compromises pancreas functionality. GDM is a common pregnancy complication that affects approximately 14% of pregnancies worldwide. It is associated with insulin resistance, in turn generated by a combined action of pregnancy hormones and other factors [5].

Substantial evidence correlates vitamin B6 to diabetes and its complications. Some population screenings have been carried out to compare PLP levels in diabetic groups vs. healthy subjects; in addition, several studies focused on the impact of vitamin B6 on diabetic complications and others on the effectiveness of vitamin B6 as a preventive treatment. Vitamin B6 levels are commonly assessed by measuring plasma pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) concentration and an inadequate vitamin B6 status is generally associated with a concentration, under the cut-off level of 30 nmol/L. Other methods include the measurement of plasma pyridoxal or total vitamin B6 and urinary 4-pyridoxic acid, as well the ratio between PLP and PL [6]. By examining the studies reported in literature, an inverse relation between vitamin B6 levels and diabetes emerges. Satyanarayana and coworkers [7] in a cross-sectional case-control study found that the mean plasma PLP levels were significantly lower in T2D subjects, compared to the healthy controls. By comparing the results obtained in a Korean study by Ahn and coworkers [8] to those obtained by Nix and collaborators [9] in a German cohort, vitamin B6 levels appeared to be inversely related to the progression of diabetes. Ahn and collaborators [8], in fact, examined diabetic people with an early status of the disease, finding a mean plasma PLP level reduction to be relevant but not statistically significant, with respect to controls; in contrasts, the diabetic group examined by Nix [9], being composed of people with advanced clinical stage, exhibited median plasma concentrations of PLP, PN, and PL that were significantly decreased in a diabetic group compared to the controls. Interestingly, median plasma levels of the PM, PMP, and pyridoxic acid were significantly higher in the diabetes groups than in the controls; this finding led Nix and collaborators to advance the hypothesis that T2D might be associated with an altered activity of the enzymes involved in the interconversion of B6 vitamers [9]. In another study, based on the evidence of increased urinary clearance of vitamin B6, it was hypothesized that decreased vitamin B6 levels in T2D subjects could derive from an impaired reabsorption processes [10]. The same inverse relationship between B6 levels and diabetes was observed in experimental animals [11][12]. Roger was the first to describe decreased PLP levels in streptozotocin-diabetic rats accompanied by less storage in the liver of the mitochondrial PLP [11].

Decreased PLP levels have also be associated with GDM. In a study performed in a group of women affected by GDM, Bennink and Schreurs [13] found that 13 out of 14 displayed reduced PLP levels. Moreover, pyridoxine administration ameliorated oral glucose tolerance. Analogous results were obtained by Spellacy and coworkers [14], which found a clear blood glucose decrease and a normalization of insulin secretion following pyridoxine therapy in GDM women, indicating that vitamin B6 might ameliorate plasma insulin biological activity.

Other intervention studies reported that pyridoxine supplementation is capable of lowering blood glucose levels in streptozotocin-treated rats [15], as well as glycosylated hemoglobin levels in T2D patients [16]. Moreover, Kim and collaborators [17] showed that vitamin B6 can reduce postprandial blood glucose levels following sucrose and starch ingestion, by inhibiting the activity of small-intestinal α-glucosidases.

2. Is Reduced Vitamin B6 Availability the Cause or the Effect of Diabetes?

Although an evident link exists between vitamin B6 and diabetes, it is not clear whether the diabetic status is responsible for decreasing PLP availability or, in contrast, whether reduced PLP levels represent a causative agent of diabetes. By examining the literature, it appears that both hypothesis might be plausibly true, suggesting the existence of a vicious circle that correlates vitamin B6 and diabetes. In this paragraph, we reported some evidence in support of each hypothesis by just mentioning some underlying mechanisms that were proposed. In Section 4, we examine in greater details, the mechanisms through which more experimental data converge.

2.1. Diabetes Decreases Vitamin B6 Levels

The first evidence that diabetes can reduce PLP levels was provided by Leklem and Hollenbeck [18] who demonstrated that the ingestion of glucose by healthy subjects caused a reduction of PLP levels. In agreement with this idea, Okada and coworkers [12] proposed that diabetes might lead to vitamin B6 deficiency as a result of an increased rate of protein metabolism, due to a diet low in carbohydrates and rich in proteins. Since PLP is cofactor for many enzymes involved in protein metabolism, an increased PLP demand would cause a decrease of PLP in other tissues. This hypothesis is based on the finding that the amount of PLP was found increased in the liver of streptozotocin-diabetic rats, with respect to the nondiabetic controls, but was reduced in the plasma, kidney, and muscles [12]. Accordingly, in diabetic rats fed a low PLP diet, the activity of aspartate amino transferase, an enzyme that is PLP-dependent and is involved in the protein metabolism, was found to be four times greater in the liver of diabetic, as compared to the non-diabetic controls. In contrast, the activity of another PLP-dependent enzyme, the glycogen phosphorylase, was decreased in the muscles of diabetic rats as compared to non-diabetic animals, although the regulation of this enzyme in the muscles also depended on many other factors.

Epidemiological, clinical, and experimental studies have indicated an association between low-grade inflammation and both T1D [19] and T2D [20][21]. Moreover, the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of T2D and vascular complications was confirmed by intervention studies [21]. In diabetic patients, an inverse relationship between plasma PLP and inflammation markers was found [9]. Therefore, it was proposed that in diabetes, the decline in PLP levels might be due to (1) the mobilization of this coenzyme to the site of inflammation; (2) increased demand by the PLP-dependent enzymes involved into the tryptophan kynurenine pathway; and (3) immune cell proliferation [22]. However, more research is needed to confirm these mechanisms.

2.2. Reduced Vitamin B6 Levels Trigger Diabetes

A cause–effect relation between low PLP levels and diabetes emerged from the work of Toyota et al. [23], which showed that pyridoxine deficiency can impair insulin secretion in rats. In addition, by performing in vitro experiments of pancreas perfusion, the authors also found that insulin and glucagon secretion was impaired in the pyridoxine deficiency.

Low vitamin B6 levels are believed to cause GDM, based on the consideration that in pregnancy, PLP levels tend to decline due to the movement of pyridoxine to fetus and, in addition, on the finding that pyridoxine treatment ameliorates glucose tolerance in GDM women [14].

Reduced vitamin B6 availability might also contribute to the appearance of pancreatic islet autoimmunity in T1D. This idea is based on the consideration that PLP is a cofactor for glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD-65), which represents an important autoantigen implicated in the pathogenesis of T1D. It was hypothesized that reduced levels of the coenzyme might trigger autoimmunity by altering stability, tridimensional conformation, or antigenicity of GAD65 [24].

The most direct evidence indicating that vitamin B6 deficiency could cause diabetes was provided by data from studies in Drosophila, showing that mutations in genes involved in vitamin B6 metabolism cause diabetes [25][26].

2.2.1. Mutations in Genes Involved in Vitamin B6 Synthesis Cause Diabetes

In pathophysiological studies, cause–effect relationships at the basis of a given disease can be inferred by examining the effects of mutations in the involved genes. This approach is difficult to pursue in human research but is widely used in model organisms. Drosophila melanogaster, a successful organism for genetic and cytogenetic studies [27], in the last 10 years, turned out to be a powerful resource to study metabolic diseases, given that the flies share 75% of genes with humans, as well as major metabolic pathways. Both T1D and T2D were modeled in flies and diabetic hallmarks, such as hyperglycemia, altered lipid metabolism, reduced body dimensions, and obesity, were extensively described [28][29][30].

Interestingly, in Drosophila, the impact of mutations on diabetes was analyzed in the genes involved in the vitamin B6 salvage pathway, such as pyridoxal kinase (dPdxk) and pyridoxine 5′-phosphate oxidase (sgll). These studies revealed that mutations in the dPdxk gene caused a significant increase in the glucose content of the larval hemolymph (the human blood) [25]. Moreover, the finding that insulin signaling is reduced in the dPdxk mutant larvae, suggested that dPdxk mutants might represent a new model of T2D [25]. In agreement with these results, the silencing of sgll by RNA interference produced diabetic hallmarks, such as hyperglycemia, reduced body size, and altered lipid metabolism [26]. Moreover, vitamin B6 administration rescues diabetic phenotypes in both Pdxk and Sgll depleted individuals, whereas the treatment with the PLP inhibitor 4-deoxypyridoxine (4-DP) causes hyperglycemia in wild type individuals [25][26][31].

Studies aimed at correlating the expression of PDXK or PNPO human genes with diabetes are still scarce, but encouraging. Moreno-Navarrete and coworkers [32] demonstrated that reduced PDXK expression impacts the lipid metabolism (see Section 4.2), raising the possibility that vitamin B6 in obesity can protect from insulin resistance. Moreover, our group also found a link between human PDXK gene and diabetes. We demonstrated that the expression, in dPdxk1 mutant flies, of 4 PDXK variants with impaired catalytic activity or affinity for substrates was unable to rescue the hyperglycemia due to dPdxk1 mutation, from the wild-type PDXK protein [33].

3. Mechanisms Underlying the Link between Vitamin B6 and Diabetes

By considering that PLP is involved in a plethora of metabolic reactions by working as a coenzyme, as well as antioxidant molecule, it is plausible that reduced vitamin B6 levels can impact different diabetic contexts, through different mechanisms. In the Section 3, some hypotheses concerning the mechanisms that relate vitamin B6 to diabetes are mentioned. In this section, the pathways on which most studies converge are analyzed in more detail.

3.1. Vitamin B6 and Tryptophan Metabolism

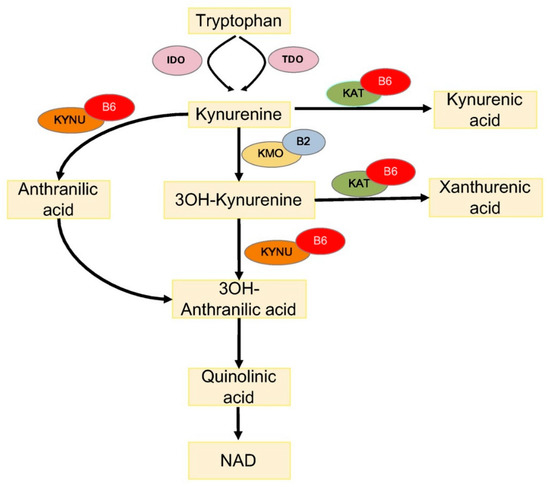

One way through which PLP impacts diabetes concerns the metabolism of tryptophan (TRP), an essential amino acid, which is a substrate for the biosynthesis of menthoxyindoles, such as serotonin, N-acetylserotonin, and melatonin. About 95% of TRP is metabolized through the kynurenine (KYN) pathway to produce NAD [34] (Figure 12). TRP- or indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenases (TDO or IDO) convert TRP to KYN and the activity of these enzymes is a rate-limiting step, increased by stress hormones or inflammatory factors (e.g., IFNG and LPS) [35]. KYN is then converted in 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HKYN), through the action of KYN-monooxygenase (KMO). KYN and 3-HKYN can be converted, respectively, in kynurenic acid (KYNA) and xanthurenic acid (XA), through the activity of the aminotransferases (KAT), which is a PLP-dependent enzyme. The conversion of 3-HKYN into the 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA) is performed by kynureninase (KYNU), which also depends on PLP for its activity. As KYNU is more sensitive to deficiency of PLP, with respect to KAT [36], PLP deficiency diverts 3-HKYN metabolism from the formation of 3-HAA, to accumulation of KYNA and XA [37][38][39][40].

Figure 12. Tryptophan metabolism via the kynurenine pathway. IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; TDO, tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase; KAT, kynurenine aminotransferase; KMO, kynurenine 3-monooxygenase; KYNU, kynureninase; 3OH-kynurenine, 3-hydroxy kynurenine; 3OH-anthranilic acid, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid; B6, vitamin B6 (pyridoxal 5′-phosphate); and B2, vitamin B2 (flavin adenine dinucleotide).

Evidence exists that the tryptophan metabolism is impaired in the different forms of diabetes, due to many factors and conditions, such as pregnancy, oral contraceptives, and emotional and metabolic stress that reduce PLP availability [13][41]. Accordingly, it was found that XA was excessively excreted in diabetic patients [42][43]. Analogously, GDM women after an oral load of TRP exhibited increased XA excretion reduced by PLP administration [13]. Similar results came from animal studies. It was shown that streptozotocin-diabetic rats on TRP treatment excreted much more XA and other TRP metabolites, compared to non-diabetic rats [44] and, more recently, metabolomic studies reported increased KYNA levels in the urine of nonhuman primate and T2D mouse models [45]. Moreover, evidence exists that the KYN pathway is activated in obesity [46] and XA levels have been found to be elevated in pre-diabetic status [47], suggesting that the TRP pathway impairment might contribute to insulin resistance, which precedes T2D [48].

Interestingly, XA has diabetogenic properties because its administration to rats induced diabetic symptoms, worsened by B6 deficiency, including pathological modifications of the pancreatic beta cell tissue [49]. It was proposed that the TRP metabolites impact diabetes through different mechanisms, which can compromise either the insulin activity or insulin secretion. TRP metabolites can be responsible for the (1) formation of chelate complexes with insulin (XA–In), which have about a 50% lower activity compared to pure insulin [50]; (2) formation of Zn++ ion–insulin complexes in β cells that cause a toxic effects on the isolated pancreatic islets [43][51]; (3) inhibition of insulin release from the rat pancreas [52], and (4) induction of pathological apoptosis of pancreatic beta cells [53].

Altered TRP metabolisms is associated with diabetic complications. An elevation in the concentrations of tryptophan metabolites and IDO expression was evident in diabetic retinopathy patients [54]. Moreover, a significant inverse association between toxic TRP metabolites and the stages of chronic kidney diseases, which occur as diabetes complications, was reported [55].

3.2. Vitamin B6 and Lipid Metabolism

Reduced vitamin B6 availability can also impact insulin resistance through the lipid metabolism. It was shown that in obese people, adipogenesis and lipotossicity can promote insulin resistance [56][57]. Contrary to previous knowledge that adipogenesis ceases early in the life with a fixed number of adipocytes, the fat cells experience a dynamic process of turnover through which the adipocytes differentiate from pre-adipocyte into mature adipocytes. During adipogenesis, a shift in the gene expression replaces the transcripts proper of the adipocyte early stage with the transcripts responsible for the final maturation [58]. It was shown that adipocyte maturation is compromised in T2D. Larger adipocytes, but similar number of fat cells, were found in diabetic individuals compared to non-diabetic people; moreover, insulin sensitivity was shown to be inversely related to fat cell size. Furthermore, the expression level of some genes involved in adipogenesis was shown to be reduced in T2D subjects, compared to obese non-diabetic individuals [59].

Vitamin B6 is involved in adipogenesis. First evidence come from works in rat models that showed that a vitamin B6-deficient diet significantly reduced adipose tissue and lipogenesis [60][61][62]. Later, it was shown that vitamin B6 administration increased intracellular lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes [63], and reduced macrophage infiltration and adipose tissue inflammation in mice [64][65]. Furthermore, it was shown that vitamin B6 is present at low circulating concentrations in obese people [66]. More recent research by Moreno-Navarrete and coworkers [32] provided more clues on the role played by vitamin B6 in adipogenesis. The authors, by examining adipose tissues from obese subjects, found lower PLP levels in visceral adipose tissues vs. subcutaneous ones; accordingly, they found the PDXK expression levels to be significantly reduced and associated with that of the adipogenic genes. In addition, they also demonstrated that PDXK mRNA levels, during adipocyte differentiation, were reduced by inflammatory conditions. Moreover, the inhibition of the PDXK activity (mediated by 4-DP) reduced adipogenic gene expression, during adipocyte differentiation, whereas PLP administration produced the opposite effect [32].

How exactly PLP regulated adipogenes is not fully elucidated. It was proposed that PLP might activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), one of the master nuclear receptor involved in the expression of adipogenesis genes [63]. Alternatively, PLP might conjugate with RIP140, a nuclear transcription factor, by enhancing its co-repressive activity and its physiological function in adipocyte differentiation [67][68]. Moreover, based on the finding that an altered DNA methylation is associated with adipose tissue dysfunction in T2D patients [69], given that PLP is a coenzyme for serine hydrossymethiltranferase (SHMT), vitamin B6 might contribute to maintain the correct methylation pattern.

Vitamin B6 might also impact the lipid metabolism, through different mechanisms. It was proposed that reduced levels of vitamin B6 might increase levels of homocysteine, as PLP is a cofactor for cystathionine-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine-lyase (CGL), which are involved in the metabolism of this compound [70]. Elevated homocysteine levels are associated with obesity; in addition, they can impair endothelial function and lead to lipid accumulation in liver [71][72][73].

The protective role of vitamin B6 against hepatic lipid accumulation is sustained by the evidence that vitamin B6 administration reduced the accumulation of lipids in livers of high-fat diet-fed Apoe−/− mice [70] and also that patients affected by nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a metabolic condition strictly linked to insulin resistance [74], exhibited decreased PLP levels [75]. Although the mechanism that links PLP to hepatic lipid accumulation needs further studies, it has also raised the possibility that vitamin B6 levels could impact NAFLD by impairing polyunsatured fatty acids (PUFA) interconversion. It was shown that vitamin B6 deficiency can contribute to reduce plasma (n-3) and (n-6) PUFA concentrations in healthy subjects [76].

References

- Roberto Contestabile; L. Di Salvo Martino; Biomedical aspects of pyridoxal 5'-phosphate availability. Frontiers in Bioscience 2012, 4, 897-913, 10.2741/e428.

- Chiara Merigliano; Elisa Mascolo; Romina Burla; Isabella Saggio; Fiammetta Vernì; The Relationship Between Vitamin B6, Diabetes and Cancer. Frontiers in Genetics 2018, 9, 388, 10.3389/fgene.2018.00388.

- Roberto Contestabile; Martino Luigi Di Salvo; Victoria Bunik; Angela Tramonti; Fiammetta Vernì; The multifaceted role of vitamin B6 in cancer: Drosophila as a model system to investigate DNA damage. Open Biology 2020, 10, 200034, 10.1098/rsob.200034.

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2013, 36 (Suppl. 1), S67–S74.

- Plows, J.F.; Stanley, J.L.; Baker, P.N.; Reynolds, C.M.; Vickers, M.H; The Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2018, 19, 3342.

- Leklem, J.E; Vitamin B-6: A status report. J. Nutr. 1990, 120 (Suppl. 11), 1503–1507.

- Alleboena Satyanarayana; Nagalla Balakrishna; Sujatha Pitla; Paduru Yadagiri Reddy; Sivaprasad Mudili; Pratti Lopamudra; Palla Suryanarayana; Kalluru Viswanath; Radha Ayyagari; G. Bhanuprakash Reddy; Status of B-Vitamins and Homocysteine in Diabetic Retinopathy: Association with Vitamin-B12 Deficiency and Hyperhomocysteinemia. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e26747, 10.1371/journal.pone.0026747.

- Hee Jung Ahn; Kyung Wan Min; Youn-Ok Cho; Assessment of vitamin B6status in Korean patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Nutrition Research and Practice 2011, 5, 34-39, 10.4162/nrp.2011.5.1.34.

- Wilfred A Nix; Rudolf Zirwes; Volkhard Bangert; Raimund Peter Kaiser; Matthias Schilling; Ulrike Hostalek; Rima Obeid; Vitamin B status in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with and without incipient nephropathy. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2015, 107, 157-165, 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.09.058.

- Hiromi Iwakawa; Yasuyuki Nakamura; Tomiho Fukui; Tsutomu Fukuwatari; Satoshi Ugi; Hiroshi Maegawa; Yukio Doi; Katsumi Shibata; Concentrations of Water-Soluble Vitamins in Blood and Urinary Excretion in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrition and Metabolic Insights 2016, 9, 85–92, 10.4137/nmi.s40595.

- K S Rogers; E S Higgins; E S Kline; Experimental diabetes causes mitochondrial loss and cytoplasmic enrichment of pyridoxal phosphate and aspartate aminotransferase activity. Biochemical Medicine and Metabolic Biology 1986, 36, 91–97.

- M Okada; M. Shibuya; E. Yamamoto; Y. Murakami; Effect of diabetes on vitamin B6 requirement in experimental animals. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 1999, 1, 221-225, 10.1046/j.1463-1326.1999.00028.x.

- H J Bennink; W H Schreurs; Improvement of oral glucose tolerance in gestational diabetes by pyridoxine. BMJ 1975, 3, 13-15, 10.1136/bmj.3.5974.13.

- W N Spellacy; W C Buhi; S A Birk; Vitamin B6 treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus: studies of blood glucose and plasma insulin. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1977, 127, 599–602.

- A R Nair; M P Biju; C S Paulose; Effect of pyridoxine and insulin administration on brain glutamate dehydrogenase activity and blood glucose control in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1998, 1381, 351–354.

- L. R. Solomon; K. Cohen; Erythrocyte O2 transport and metabolism and effects of vitamin B6 therapy in type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 1989, 38, 881-886, 10.2337/diabetes.38.7.881.

- Hyuk Hwa Kim; Yu-Ri Kang; Jung-Yun Lee; Hung-Bae Chang; Ki Won Lee; Emmanouil Apostolidis; Young-In Kwon; The Postprandial Anti-Hyperglycemic Effect of Pyridoxine and Its Derivatives Using In Vitro and In Vivo Animal Models. Nutrients 2018, 10, 285, 10.3390/nu10030285.

- J E Leklem; C B Hollenbeck; Acute ingestion of glucose decreases plasma pyridoxal 5’-phosphate and total vitamin B-6 concentration. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1990, 51, 832-836, 10.1093/ajcn/51.5.832.

- Matthew Clark; Charles J. Kroger; Roland Tisch; Type 1 Diabetes: A Chronic Anti-Self-Inflammatory Response. Frontiers in Immunology 2017, 8, 1898, 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01898.

- Nathalie Esser; Sylvie Legrand-Poels; J Piette; André J Scheen; Nicolas Paquot; Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2014, 105, 141-150, 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.04.006.

- Alan R. Saltiel; Jerrold Olefsky; Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2017, 127, 1-4, 10.1172/JCI92035.

- Ligi Paul; Per Magne Ueland; Jacob Selhub; Mechanistic perspective on the relationship between pyridoxal 5'-phosphate and inflammation. Nutrition Reviews 2013, 71, 239-244, 10.1111/nure.12014.

- Takayoshi Toyota; Yukihiro Kai; Masaei Kakizaki; Hidetsugu Ohtsuka; Yukio Shibata; Yoshio Goto; The endocrine pancreas in pyridoxine deficient rats. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine 1981, 134, 331-336, 10.1620/tjem.134.331.

- B. Rubi; Pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (PLP) deficiency might contribute to the onset of type I diabetes. Medical Hypotheses 2012, 78, 179-182, 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.10.021.

- Antonio Marzio; Chiara Merigliano; Maurizio Gatti; Fiammetta Vernì; Sugar and Chromosome Stability: Clastogenic Effects of Sugars in Vitamin B6-Deficient Cells. PLOS Genetics 2014, 10, e1004199, 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004199.

- Elisa Mascolo; Noemi Amoroso; Isabella Saggio; Chiara Merigliano; Fiammetta Vernì; Pyridoxine/pyridoxamine 5′‐phosphate oxidase (Sgll/PNPO) is important for DNA integrity and glucose homeostasis maintenance in Drosophila. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2020, 235, 504-512, 10.1002/jcp.28990.

- Francesca Cipressa; Sabrina Romano; Silvia Centonze; Petra I. Zur Lage; Fiammetta Vernì; Patrizio Dimitri; Maurizio Gatti; Giovanni Cenci; Effete, a Drosophila Chromatin-Associated Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme That Affects Telomeric and Heterochromatic Position Effect Variegation. Genetics 2013, 195, 147-158, 10.1534/genetics.113.153320.

- L. P. Musselman; J. L. Fink; K. Narzinski; P. V. Ramachandran; S. S. Hathiramani; R. L. Cagan; Thomas J. Baranski; A high-sugar diet produces obesity and insulin resistance in wild-type Drosophila. Journal of Cell Science 2011, 124, 842–849, 10.1242/jcs.102947.

- Ronald W. Alfa; Seung K. Kim; Using Drosophila to discover mechanisms underlying type 2 diabetes. Disease Models & Mechanisms 2016, 9, 365-376, 10.1242/dmm.023887.

- P. Graham; Leslie Pick; Drosophila as a Model for Diabetes and Diseases of Insulin Resistance. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 2017, 121, 397-419, 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.07.011.

- Chiara Merigliano; Elisa Mascolo; Mattia La Torre; Isabella Saggio; Fiammetta Vernì; Protective role of vitamin B6 (PLP) against DNA damage in Drosophila models of type 2 diabetes. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 11432, 10.1038/s41598-018-29801-z.

- José María Moreno-Navarrete; Mariona Jove; Francisco J Ortega; Gemma Xifra; Wifredo Ricart; Elia Obis; Reinald Pamplona; Manuel Portero-Otin; José-Manuel Fernández-Real; Metabolomics uncovers the role of adipose tissue PDXK in adipogenesis and systemic insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 822-832, 10.1007/s00125-016-3863-1.

- Elisa Mascolo; Anna Barile; Lorenzo Stufera Mecarelli; Noemi Amoroso; Chiara Merigliano; Arianna Massimi; Isabella Saggio; Tine Willum Hansen; Angela Tramonti; Martino Luigi Di Salvo; et al.Fabrizio BarbettiRoberto ContestabileFiammetta Vernì The expression of four pyridoxal kinase (PDXK) human variants in Drosophila impacts on genome integrity. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 14188, 10.1038/s41598-019-50673-4.

- Robert Schwarcz; John P. Bruno; Paul J. Muchowski; Hui-Qiu Wu; Kynurenines in the mammalian brain: when physiology meets pathology. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2012, 13, 465-77, 10.1038/nrn3257.

- Oxenkrug, G.F. Genetic and hormonal regulation of tryptophan kynurenine metabolism: Implications for vascular cognitive impairment, major depressive disorder, and aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1122, 35–49.

- Jennifer L. Van De Kamp; Andrew Smolen; Response of kynurenine pathway enzymes to pregnancy and dietary level of vitamin B-6. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 1995, 51, 753-758, 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00026-s.

- David A. Bender; Eliud N. M. Njagi; Paul Danielian; Tryptophan metabolism in vitamin B6-deficient mice. British Journal of Nutrition 1990, 63, 27-36, 10.1079/bjn19900089.

- Luisa Rios-Avila; H. Frederik Nijhout; Michael C. Reed; Harry S. Sitren; Jesse Gregory; A mathematical model of tryptophan metabolism via the kynurenine pathway provides insights into the effects of vitamin B-6 deficiency, tryptophan loading, and induction of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase on tryptophan metabolites. The Journal of Nutrition 2013, 143, 1509-19, 10.3945/jn.113.174599.

- Norma Yess; J. M. Price; R. R. Brown; Hellen Linkswiler; Patricia B. Swan; Vitamin B6 Depletion in Man: Urinary Excretion of Tryptophan Metabolites. The Journal of Nutrition 1964, 84, 229-236, 10.1093/jn/84.3.229.

- Fumio Takeuchi; Ryoko Tsubouchi; Sukehisa Izuta; Yukio Shibata; Kynurenine metabolism and xanthurenic acid formation in vitamin B6-deficient rat after tryptophan injection.. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 1989, 35, 111-122, 10.3177/jnsv.35.111.

- J.H. Connick; Trevor W. Stone; The role of kynurenines in diabetes mellitus. Medical Hypotheses 1985, 18, 371-376, 10.1016/0306-9877(85)90104-5.

- M Hattori; Y Kotake; Studies on the urinary excretion of xanthurenic acid in diabetics.. Acta vitaminologica et enzymologica 1984, 6, 221–228.

- Ikeda, S.; Kotake, Y. Urinary excretion of xanthurenic acid and zinc in diabetes: (3). Occurrence of xanthurenic acid-Zn2+ complex in urine of diabetic patients and of experimentally-diabetic rats. Ital. J. Biochem. 1986, 35, 232–241.

- N. R. Akarte; N. V. Shastri; Studies on Tryptophan-Niacin Metabolism in Streptozotocin Diabetic Rats. Diabetes 1974, 23, 977-981, 10.2337/diab.23.12.977.

- Andrew Patterson; Jessica A. Bonzo; Fei Li; Kristopher W. Krausz; Gabriel S. Eichler; Sadaf Aslam; Xenia Tigno; John N. Weinstein; Barbara C. Hansen; Jeff Idle; Frank J. Gonzalez; Metabolomics Reveals Attenuation of the SLC6A20 Kidney Transporter in Nonhuman Primate and Mouse Models of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 19511-19522, 10.1074/jbc.M111.221739.

- Favennec, M.; Hennart, B.; Caiazzo, R.; Leloire, A.; Yengo, L.; Verbanck, M.; Arredouani, A.; Marre, M.; Pigeyre, M.; Bessede, A.; et al.et al The kynurenine pathway is activated in human obesity and shifted toward kynurenine monooxygenase activation. Obesity 2015, 23, 2066–2074.

- V G Manusadzhian; Iu A Kniazev; L L Vakhrusheva; [Mass spectrometric identification of xanthurenic acid in pre-diabetes]. Voprosy meditsinskoi khimii 1974, 20, 95–97.

- Gregory Oxenkrug; Insulin resistance and dysregulation of tryptophan-kynurenine and kynurenine-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolic pathways.. Molecular Neurobiology 2013, 48, 294-301, 10.1007/s12035-013-8497-4.

- Yahito Kotake; XANTHURENIC ACID, AN ABNORMAL METABOLITE OF TRYPTOPHAN AND THE DIABETIC SYMPTOMS CAUSED IN ALBINO RATS BY ITS PRODUCTION. THE JOURNAL OF VITAMINOLOGY 1955, 1, 73-87, 10.5925/jnsv1954.1.2_73.

- Kotake, Y.; Ueda, T.; Mori, T.; Igaki, S.; Hattori, M. Abnormal tryptophan metabolism and experimental diabetes by xanthurenic acid (XA). Acta Vitaminol. Enzymol. 1975, 29, 236–239.

- G Meyramov; V Korchin; N Kocheryzkina; Diabetogenic activity of xanturenic acid determined by its chelating properties?. Transplantation Proceedings 1998, 30, 2682-2684, 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00788-x.

- K. S. Rogers; S. J. Evangelista; 3-Hydroxykynurenine, 3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid, and o-Aminophenol Inhibit Leucine-Stimulated Insulin Release from Rat Pancreatic Islets. Experimental Biology and Medicine 1985, 178, 275-278, 10.3181/00379727-178-42010.

- Halina Z Malina; Christoph Richter; Martin Mehl; Otto M Hess; Pathological apoptosis by xanthurenic acid, a tryptophan metabolite: activation of cell caspases but not cytoskeleton breakdown. BMC Physiology 2001, 1, 7.

- Praveen Kumar Munipally; Satish G. Agraharm; Vijay Kumar Valavala; Sridhar Gundae; Naga Raju Turlapati; Evaluation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression and kynurenine pathway metabolites levels in serum samples of diabetic retinopathy patients. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry 2011, 117, 254-258, 10.3109/13813455.2011.623705.

- Subrata Debnath; Chakradhar Velagapudi; Laney Redus; Farook Thameem; Balakuntalam Kasinath; Claudia E Hura; Carlos Lorenzo; Hanna E Abboud; Jason C. O'connor; Tryptophan Metabolism in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease Secondary to Type 2 Diabetes: Relationship to Inflammatory Markers. International Journal of Tryptophan Research 2017, 10, 1178646917694600.

- Miriam Cnop; Fatty acids and glucolipotoxicity in the pathogenesis of Type 2 diabetes. Biochemical Society Transactions 2008, 36, 348-352, 10.1042/bst0360348.

- Michele Longo; Federica Zatterale; Jamal Naderi; Luca Parrillo; Pietro Formisano; Gregoryalexander Raciti; Francesco Beguinot; Claudia Miele; Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 2358, 10.3390/ijms20092358.

- Sung Sik Choe; Jin Young Huh; In Jae Hwang; Jong In Kim; Jae Bum Kim; Adipose Tissue Remodeling: Its Role in Energy Metabolism and Metabolic Disorders. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2016, 7, 30, 10.3389/fendo.2016.00030.

- Severine G. Dubois; Leonie K. Heilbronn; Steven R. Smith; Jeanine B. Albu; David E. Kelley; Eric Ravussin; Look AHEAD Adipose Research Group; Decreased Expression of Adipogenic Genes in Obese Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes*. Obesity 2006, 14, 1543-52, 10.1038/oby.2006.178.

- Agnes M. Huber; Stanley N. Gershoff; D. Mark Hegsted; Carbohydrate and Fat Metabolism and Response to Insulin in Vitamin B6-deficient Rats. The Journal of Nutrition 1964, 82, 371-378, 10.1093/jn/82.3.371.

- J D Ribaya; S N Gershoff; Effects of vitamin B6 deficiency on liver, kidney, and adipose tissue enzymes associated with carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, and on glucose uptake by rat epididymal adipose tissue. The Journal of Nutrition 1977, 107, 443–452.

- R. Radhakrishnamurty; J. F. Angel; Z. I. Sabry; Response of Lipogenesis to Repletion in the Pyridoxine-deficient Rat. The Journal of Nutrition 1968, 95, 341-348, 10.1093/jn/95.3.341.

- Noriyuki Yanaka; Mayumi Kanda; Keigo Toya; Haruna Suehiro; Norihisa Kato; Vitamin B6 regulates mRNA expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ target genes. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2011, 2, 419-424, 10.3892/etm.2011.238.

- Yohei Sanada; Takahiro Kumoto; Haruna Suehiro; Fusanori Nishimura; Norihisa Kato; Yutaka Hata; Alexander Sorisky; Noriyuki Yanaka; RASSF6 Expression in Adipocytes Is Down-Regulated by Interaction with Macrophages. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61931, 10.1371/journal.pone.0061931.

- Sanada, Y.; Kumoto, T.; Suehiro, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Nishimura, F.; Kato, N.; Yanaka, N; IκB kinase epsilon expression in adipocytes is upregulated by interaction with macrophages. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 1357–1362.

- Erlend Tuseth Aasheim; Dag Hofsø; Jøran Hjelmesaeth; Kåre I Birkeland; Thomas Bøhmer; Vitamin status in morbidly obese patients: a cross-sectional study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008, 87, 362–369.

- M D Mostaqul Huq; Nien-Pei Tsai; Ya-Ping Lin; LeeAnn Higgins; Li-Na Wei; Vitamin B6 conjugation to nuclear corepressor RIP140 and its role in gene regulation. Nature Methods 2007, 3, 161-165, 10.1038/nchembio861.

- Ranjana P. Bird; The Emerging Role of Vitamin B6 in Inflammation and Carcinogenesis. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research 2018, 83, 151-194, 10.1016/bs.afnr.2017.11.004.

- Emma Nilsson; Per Anders Jansson; Alexander Perfilyev; Petr Volkov; Maria Pedersen; M.K. Svensson; Pernille Poulsen; Rasmus Ribel-Madsen; Nancy L. Pedersen; Peter Almgren; Joao Fadista; Tina Rönn; Bente Klarlund Pedersen; Camilla Scheele; Allan Vaag; C. Ling; Altered DNA Methylation and Differential Expression of Genes Influencing Metabolism and Inflammation in Adipose Tissue From Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2962-2976, 10.2337/db13-1459.

- Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Zhao, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.M.; Wang, S.X; Vitamin B6 Prevents Endothelial Dysfunction, Insulin Resistance, and Hepatic Lipid Accumulation in Apoe (−/−) Mice Fed with High-Fat Diet. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 1748065.

- James B. Meigs; Paul F. Jacques; Jacob Selhub; Daniel E. Singer; David M. Nathan; Nader Rifai; Ralph B. D’Agostino; Peter W.F. Wilson; Fasting plasma homocysteine levels in the insulin resistance syndrome: the Framingham offspring study.. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 1403-1410, 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1403.

- Oluwabukola A. Ala; Adeseye A. Akintunde; Rosemary T. Ikem; Babatope A. Kolawole; Olufemi O. Ala; T.A. Adedeji; Association between insulin resistance and total plasma homocysteine levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in south west Nigeria. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2017, 11, S803-S809, 10.1016/j.dsx.2017.06.002.

- Elena Azzini; Stefania Ruggeri; Angela Polito; Homocysteine: Its Possible Emerging Role in At-Risk Population Groups. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 1421, 10.3390/ijms21041421.

- Tawfik Khoury; Ami Ben Ya'acov; Yehudit Shabat; Lidya Zolotarovya; Ram Snir; Yaron Ilan; Altered distribution of regulatory lymphocytes by oral administration of soy-extracts exerts a hepatoprotective effect alleviating immune mediated liver injury, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and insulin resistance. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2015, 21, 7443-7456, 10.3748/wjg.v21.i24.7443.

- Li, F.J.; Zheng, S.R.; Wang, D.M; Adrenomedullin: An important participant in neurological diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 1199–1207.

- Mei Zhao; Yvonne Lamers; Maria A. Ralat; Bonnie S. Coats; Yueh-Yun Chi; Keith E. Muller; James R. Bain; Meena N. Shankar; Christopher B. Newgard; Peter W. Stacpoole; et al.Jesse Gregory Marginal vitamin B-6 deficiency decreases plasma (n-3) and (n-6) PUFA concentrations in healthy men and women. The Journal of Nutrition 2012, 142, 1791-7, 10.3945/jn.112.163246.