Neuropeptide oxytocin (OXT) has the capacity to modulate a wide spectrum of physiological and cognitive processes including motivation, learning, emotion, and the stress response playing a role in substance use disorders.

- oxytocin

- drug addiction

- social stress

- corticotropin-releasing factor

- reward system

- animal models

- human research

- neuroinflammation

1. Endogenous Oxytocin (OTX) System

There is huge scientific interest in the neuropeptide oxytocin (OXT) due to its putative capacity to modulate a wide spectrum of physiological and behavioral effects. It is mainly synthetized in the supraoptic nucleus (SON) and the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, and the majority is released into the peripheral bloodstream through neurohypophysis [1]. In the periphery, OXT acts as a hormone that modulates parturition, lactation, and sexual stimulation, among other functions [2]. Within the central nervous system (CNS), oxytocinergic neurons project from the hypothalamus to a variety of brain regions such as the nucleus accumbens (NAc), prefrontal cortex (PFC), anterior olfactory nucleus, lateral septum (LS), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), amygdala, and hippocampus [1].

The oxytocin receptor (OXTR) is a member of the rhodopsin-type 1 G protein-coupled receptor family, and the expression of these receptors is believed to fluctuate in a sex-dependent and species-specific manner [3]. These receptors are expressed in several tissues outside the CNS such as the heart, kidney, thymus, adipocyte tissue, gastrointestinal tract, mammary glands, and uterus [2]. Brain OXTRs are widely distributed and densely expressed in areas that are key to the regulation of social behavior, emotion, and motivation such as the mesolimbic circuit (including the PFC), NAc, and ventral tegmental area (VTA), among others [2][3][2,3].

This vast distribution of OXTR illustrates how OXT modulates a wide array of physiological and cognitive processes [2][4][2,4]. Considering its potential to modulate motivation, learning, emotion, and the stress response, it is a crucial component to be taken into consideration when addressing an individual’s vulnerability or resilience to developing a substance use disorder [5]. Moreover, the oxytocinergic system is reported to be altered after acute and chronic consumption of drugs of abuse, thus highlighting a possible use of exogenous OXT as a therapeutic tool in recovery from substance use disorders [6].

2. Drug Exposure Alters Oxytocin Neurotransmission

Clinical and preclinical studies suggest that oxytocinergic function in the brain is altered after acute or chronic exposure to drugs [6]. Preclinical studies show that acute exposure to psychostimulants such as cocaine can alter OXT levels in several brain areas. In a classic study, Johns, Caldwell, and Pedersen [7] found that two injections per day of 15 mg/kg cocaine over two days reduced hippocampal OXT in female rats, while no differences were observed in other structures such as the VTA or amygdala. Moreover, an up-regulation of OXTR in structures such as the piriform cortex, amygdala, NAc, and LS is usually observed after chronic psychostimulant administration in male rodents [8][9][8,9]. Interestingly, some studies have found that the dysfunction of the OXT system after psychostimulant administration can negatively affect several social and affiliative behaviors that are mediated by OXT such as pair bonding [10].With respect to opiates, acute administration of morphine has been reported to reduce hypothalamic OXT release in lactating females [11], whereas other studies have found increased OXT immunoreactivity in the amygdala, hippocampus, and basal forebrain of male mice [12]. It has been hypothesized that these differential effects of acute opiate administration on OXT activity are dependent on the brain structure in question or the sex of the animal [13]. When considering the effects of chronic opioid administration over the OXT system, Zanos and collaborators [13][14][13,14] described different examples of hypofunction such as reduced OXT synthesis, decreased OXT plasmatic levels, decreased OXT immunoreactivity in the hippocampus, and decreased OXT mRNA levels within the SON, arcuate, and median eminence nucleus of the hypothalamus. As a consequence, a compensatory increase in OXTR binding has been observed in different brain areas such as the olfactory nuclei and the amygdala, which should be taken into consideration when deciding a possible OXT dose in subjects chronically exposed to opiates [13].A similar pattern has been described regarding the effects of ethanol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. After chronic ethanol administration, abstinent male rats exhibit decreased levels of OXT in the brain and increased levels of OXTR in frontal and striatal areas [15], while chronic exposure to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol downregulates OXT-NP mRNA expression in the VTA and NAc [16].Clinical evidence of the impact of drug consumption on the OXT system is mainly derived from two types of studies: the analysis of plasmatic OXT levels in dependent and non-dependent subjects, and post-mortem studies. Broadly, clinical studies are in concordance with the aforementioned pre-clinical results, and confirm a similar dynamic change in the OXT system. For instance, acute alcohol consumption has been shown to decrease plasmatic OXT levels in women [17], while chronic exposure commonly produces a dysregulation of plasmatic OXT levels in men [18], in addition to neuroadaptations such as increases in OXTR mRNA and binding levels in frontal and striatal brain areas in post-mortem samples from alcohol-dependent male subjects [15].To summarize, clinical and preclinical evidence suggests that repeated exposure to drugs leads to a drop in OXT levels that seems to be related to a decrease in its synthesis [19]. While the exact mechanism that drives the decrease of OXT synthesis is not fully understood [20], the consequences of this OXT hypofunction are better ascertained and have been related to compensatory changes that upregulate OXTR in different brain areas [9][20][9,20]. These neuroadaptive changes in the endogenous OXT system mainly comprise brain regions involved in addiction and stress-related behaviors [6]. Discrepancies in the literature regarding the direction of OXT changes may be due to the brain region being analyzed [5] and the stage of the addictive cycle (acute administration, long-term dependence, or abstinence).

3. OXT Modulates the Addictive Cycle

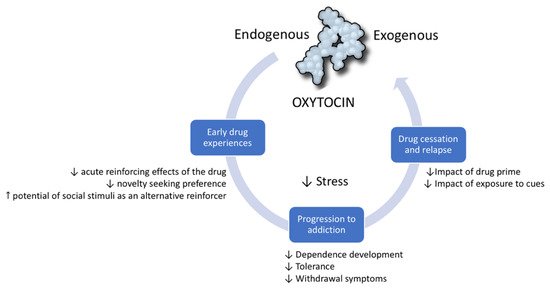

The relationship between drugs of abuse and OXT is reciprocal. A vast body of scientific literature shows that, similar to the way drugs of abuse dysregulate the endogenous OXT system, OXT can modulate the individual’s response to drugs. The therapeutic potential of OXT has been studied in all stages of the addiction cycle [21]. It has been shown to be protective in the initial stages of addiction as it diminishes behavioral and physiological responses to drugs. Preclinical evidence suggests that OXT prevents the progression from initial experimentation with a drug to dependence and escalation of drug-taking. Finally, OXT is a promising target in the management of drug abstinence and the rebalancing of brain functions after chronic exposure to drugs. In this section, we develop the hypothesis that this therapeutic potential is due to the way OXT modulates core neurobiological systems and processes that underlie the development of substance use disorders [21] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Oxytocin modulates the addiction cycle. Clinical and preclinical studies show that oxytocin has protective effects during all stages of the addiction cycle: (1) In early drug experiences, it diminishes the reinforcing and general effects of drugs. (2) It can prevent progression from initial drug experimentation to dependence and drug escalation. (3) In drug cessation, it can prevent relapse induced by cues, drug primes, and stress.

3.1. OXT in Early Stages of Addiction

During the early stages of addiction, drug taking is motivated mainly by the acute reinforcing effects of the drug [22]. The positive sensation or pleasure that is experienced is mediated by an increase in dopaminergic activity in the mesocorticolimbic system, which is also implicated in the development of neuroadaptations that underlie context-associated memories and the attachment to incentive salience to drug-related stimuli [22]. There is clear evidence that the neuropeptide OXT interacts with the reward system, and that the rewarding effects of pair bonding, sexual contact, and social interaction depend on the actions of OXT in the mesocorticolimbic circuit [23]. Additional evidence suggests that OXT is also able to interfere with the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse, mainly through its modulatory effect on dopamine (DA) activity in key regions such as the NAc, VTA, and PFC [24].

OXT administration has been shown to reduce drug-induced increases in DA in different mesolimbic regions including the NAc [24][25][24,25]. For instance, Sarnyai and collaborators [26] found that OXT administration (1 µg/µL) directly into the NAc blocked cocaine-induced increases in DA release in male mice. Similarly, other studies with psychostimulants reported that intracerebroventricular (2.5 μg/µL) or peripheral (1 mg/kg) administration of OXT blocked methamphetamine-induced increases in DA activation in the NAc in male rodents [27][28][27,28], an effect observed with other drugs such as alcohol. Peters and collaborators [25] found that intracerebroventricular administration of OXT (1 µg/5 µL) blocked the increase of DA in the NAc shell after ethanol administration in naïve and chronically treated male rats, and attributed the subsequent decrease of ethanol consumption in a self-administration (SA) paradigm to this effect.

There is evidence that a positive social environment plus a well-developed endogenous OXT system is a protective factor that diminishes an individual’s vulnerability to become initiated in the addictive cycle [29]. One of the mechanisms put forward to explain this effect is that OXT decreases novelty seeking and the initial response to drug reward [29][30][29,30]. Novelty seekers display a preference for novel environments and stimuli over familiar ones [31], and this behavioral trait has been linked to an increased risk of drug abuse in both humans and animal models [29][32][29,32]. For instance, rodent studies show that rats that display an enhanced locomotor response to a novel context also display an enhanced response to psychostimulant drugs and a faster acquisition of SA behavior [33]. Tops et al. [29] posited that an increased tone of endogenous OXT alters DA, serotonin, and endogenous opioid neurotransmission, thus promoting a shift in novelty processing from ventral to dorsal striatal structures and a subsequent decrease of preference and emotional reactivity to these contexts.

This protective effect of OXT in naïve animals during their first contacts with drugs has also been reported when OXT levels are acutely increased pharmacologically. For instance, the administration of intracerebroventricular OXT (2.5 μg/µL) to male mice prior to a methamphetamine conditioned place preference (CPP) protocol inhibited the acquisition of CPP for the context associated with the drug [34]. Moreover, repeated increases in OXT levels induced by pharmacological administration have been found to induce long-lasting neuroadaptive changes. In this regard, the repeated administration of OXT (1 mg/kg) during adolescence has been reported to decrease ethanol consumption and methamphetamine SA during adulthood in female and male rodents [35][36][35,36].

In addition, OXT has been shown to enhance the value of social stimuli, which in turn can act as an alternative reinforcer that changes the focus from drug reward to social reward [37]. For instance, Venniro and collaborators [38] found that in the presence of two possible rewards, social interaction versus the drug, rats that had developed methamphetamine SA behavior preferred the social reward. This effect has also been reported regarding the creation of drug-context-associated learning. For example, positive social interaction is rewarding enough to induce a strong conditioned preference [39] that can compete with the previously established conditioned preference for cocaine [40].

3.2. OXT in the Progression to Addiction

OXT also has the potential to prevent the progression of the addictive cycle by stemming the development of dependence and the appearance of behavioral alterations after continuous contact with the drug [6][20][6,20]. The initial motivation to consume a drug is first driven by positive reward experiences; however, after repeated drug consumption, there is a shift of motivation to avoid the negative emotional state that emerges during abstinence [22].

Dependence is a state in which drug users display neuroadaptive alterations within the reward system and in other brain structures such as those implicated in the stress response [22]. OXT has been found to attenuate the development of tolerance and dependence, and this effect has also been related to its potential to modulate DA neurotransmission in the mesocorticolimbic circuit [41]. In this regard, endogenous OXT attenuates the development of tolerance to the analgesic effects of opiates, a phenomenon that has been demonstrated by intracerebroventricular administration of selective OXT antagonists to tolerant male mice, which induces a further decrease in the analgesic effect of morphine [42][43][42,43]. OXT (5 or 0.5 µg) also reduces tolerance to the sedative and hypothermic effects of ethanol [44] and modulates psychostimulant-induced stereotypy and locomotor sensitization [45]. Based on its potential to prevent the development of tolerance, it has been posited that OXT exerts a general attenuation of the neuroadaptations that underlie drug addiction [41][46][41,46].

Finally, it has been demonstrated that OXT is useful in the management of long- and short-term abstinence [21]. During abstinence, individuals generally experience negative somatic symptomatology, hypohedonia (reduced response to natural reward), stress, and anxiety, all of which drive drug seeking and consumption to relieve this negative emotional state [22]. An exhaustive description of the neurobiological mechanism that sustains the so-called “dark side of addiction” can be found in Koob and Volkow [22]. In short, this negative affect stage is the result of hypodopaminergic activity in the reward system, while there is hyperactivity in the brain stress system and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Clinical and preclinical studies show that acute OXT administration can decrease both somatic and motivational symptoms of withdrawal from different drugs of abuse [21]. Generally, preclinical studies show that OXT can decrease withdrawal symptoms such as facial fasciculations, convulsion, hypothermia, and anxiety-like and depression-like behavior during morphine, cocaine, nicotine, and alcohol abstinence (an exhaustive review can be found in Bowen and Neumann [21]). For instance, when Szabó and co-workers [47] injected different doses of OXT (0.02, 0.2, and 2 IU) to alcohol-dependent male mice, they found that withdrawal convulsions decreased in a dose-dependent manner. This potential of OXT to decrease alcohol withdrawal has also been tested in a small sample of humans in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial, with positive results. Pedersen and collaborators [48] administered intranasal OXT (24 IU) twice daily for three days to alcohol-dependent patients admitted for medical detoxification. Their results showed that OXT-treated patients self-reported less severe withdrawal symptoms including craving, and required less lorazepam during their detoxification treatment. Similarly promising results have been obtained in other clinical trials with different drugs of abuse. For example, Stauffer and collaborators [49] found that intranasal OXT administration (40 IU) decreased cocaine and heroin craving in patients in methadone maintenance treatment. However, although preclinical studies provide strong evidence that OXT decreases withdrawal symptoms, clinical studies of OTX are still at an early stage, and mixed results have been reported [41].

3.3. OXT in the Prevention of Reinstatement and Relapse into Drug Use

Three classic triggers provoke relapse into drug seeking: exposure to drug cues, drug priming, and stressful experiences. Preclinical studies highlight the potential of OXT to impede the activation of the NAc by these factors, therefore decreasing its potential to promote a reinstatement of drug seeking behavior [21]. In this regard, Cox and collaborators [50][51][50,51] found that peripheral administration of OXT (1 mg/kg) prior to drug-paired cues, pharmacological stress, or drug-priming decreased the reinstatement of drug seeking in female and male rats in a methamphetamine SA paradigm.

In human studies, a single acute dose of intranasal OTX (20 IU) has been shown to reduce the craving for tobacco induced by cues in abstinent smokers of both sexes [52], though it has been reported not to diminish the craving for tobacco induced by social stress with a high dose (40 IU) [53][54][53,54]. OXT produces mixed effects with regard to modulating craving of cannabis, which may be determined by the level of dependence; for instance, it was shown to decrease craving induced by social stress in dependent individuals [55], while no effects were observed in recreational users [56].

The anti-stress effect of OXT may be one of the mechanisms underlying its therapeutic potential. Stress is considered to be a risk factor in all stages of the addictive process, first by increasing vulnerability to drug experimentation, then by enhancing the risk of developing dependence, and finally by provoking relapse during drug cessation [57]. Additionally, physical and social stress has been demonstrated to prime the immune system into a pro-inflammatory state, which in turn has been shown to modulate vulnerability to develop several health problems including drug addiction [58]. OXT has anti-stress and anti-inflammatory effects, and also enhances the stress-buffering effects of other interventions such as social support [59][60][61][59,60,61]. This effect can be explained broadly due to its potential to decrease the reactivity of the HPA axis by reducing the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) [1].