Genome editing technology is a flexible engineering tool for genetic manipulation of microorganisms including fungi.

- gene editing techniques

- CRISPR/Cas9

- medically important fungi

1. Introduction

The fungi represent a large, diverse group of eukaryotic microorganisms that have a small genome size, short timeframes for growth and reproduction, and share homologous genes with humans [1]. Aspergillus, Candida, and Cryptococcus are the major fungal genera that cause opportunistic and life-threatening mycoses [2,3][2][3]. Over the past decades, genetic engineering has paved the way for the desired modifications by gene manipulation using a wide range of methods [4,5][4][5]. Genetic tools have been widely used to understand the virulence potential and pathobiology of fungal infections [6], as well as patterns of resistance development against antifungals [7]. Genome editing is a very useful tool which allows manipulation of a target site in a shorter period of time [8,9][8][9].

2. Genome Editing Technologies

2.1. RNA Interference (RNAi)

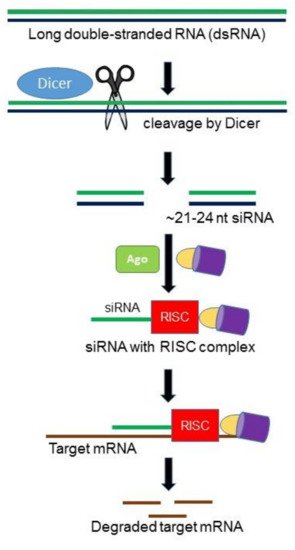

RNA interference (RNAi) is an RNA-mediated, sequence specific gene silencing mechanism involved in multiple biological processes, particularly in host defense and gene regulation [10,11][10][11]. RNAi is initiated by a RNAse III enzyme (Dicer) that cleaves a long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) into double stranded ~21–24 nucleotides small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Each siRNA consists of a guide strand and passenger strand. As guide strand becomes part of an active RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), the passenger strand is degraded by the following cellular events in the cytoplasm. The guide strand of the siRNA–RISC complex base-pairs with the complementary mRNA target sequences and initiates endonucleolytic cleavage by induced Argonaute protein (AGO; catalytic component of the RISC complex), which prevents translation of the target transcript (Figure 1). Different components of the fungal RNAi machinery not only play key roles in fungal growth and development, but also important in pathogenesis. In designing a single siRNA or an RNAi hairpin construct capable of producing a number of siRNAs specific for the target gene, it is important that the siRNA(s) targeting the mRNA must have a high efficiency of silencing as well as a low probability of binding to off-target mRNAs.

Figure 1. Hypothetical model of RNA interference (RNAi) pathway in fungi. The Dicer ribonuclease III enzyme (DCR) cleaves exogenous long double-stranded RNA (dsRNAs) into ~21–24 nucleotide small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). The guide siRNA then loaded onto the major catalytic component called Argonaute (Ago) and other proteins generating the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). siRNA, along with RISC, complementarily pair with messenger RNA (mRNA) resulting in degradation of mRNAs.

Impact of RNAi on the cyp51A gene in the itraconazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus has shown that in addition to reducing the expression of the cyp51A gene, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of itraconazole has also decreased [12]. Previous studies showed that the deletion of ERG3 and ERG11 genes in C. albicans isolates induced increased azole sensitivity [13,14][13][14]. Moreover, deletion of these genes impaired the invasion of C. albicans into the oral mucosa [15]. Epigenetic pathways establish drug resistance in fungi by affecting a number of chromatin or RNA modifications. The changes caused by RNA are induced through small RNAs (sRNAs) and RNAi. A type of genetic mutation that contributes to resistance to rapamycin and FK506 has also been identified in Mucor circinelloides through RNAi pathway. Histone acetylation also activates the epigenetic machinery of chromatin. The acetylation process, which influences the nature of histone, has been shown to be one of the mechanisms of drug resistance in C. albicans [16,17][16][17]. Histone deacetylation-induced chromatin alteration was revealed as a function of HDAC genes which directly affects the virulence of the microorganism [18,19][18][19]. RNAi has been used as an important reverse genetics approach to understand gene function in fungi. It is inexpensive and enables us to carry out high-throughput interrogation of gene function [20,21][20][21]. However, one of the major disadvantages of RNAi is that it provides only temporary inhibition of gene function and unpredictable off-target effects [22].

2.2. Restriction Enzymes

Restriction enzymes are among the first generation of genome editing tools used in the field of medical mycology. These enzymes are designed to induce genome changes by cutting DNA molecules at defined points and inserting new genes at the cutting sites [23]. This mechanism of action of the restriction enzymes has made them a valuable method for cloning. However, the major issue with this method is that it is not easy to specify in advance where exactly the gene will be inserted, as the recognition sequences of most restriction enzymes are just a few base pairs long and often repeat several times in a genome. Moreover, the specificity of a restriction enzyme is dependent on environmental conditions. Since the discovery of restriction enzymes in the early 1970s, they have been widely used for the genetic manipulation of medically important fungi. Restriction enzyme mediated integration (REMI) has been employed to create mutants in medically relevant fungi including C. albicans, A. nidulans, and A. fumigatus [24,25][24][25]. However, it is important to note that in C. albicans, only heterozygous mutations are obtained. Aspergillus and Candida spp. are best examples of pathogenic fungi in which azole resistance mechanisms have been explored using the ability of restriction enzymes to provide a series of genetic patterns [26,27,28][26][27][28].

2.3. Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs)

Due to the mentioned limitations regarding restriction enzymes, scientists looked for ways of improving the precision of these enzymes and altering them so that they could distinguish a unique sequence in the genome. Zinc finger nucleases are examples of such unique sequences [29].

The efficiency of ZFNs as a gene editing tool is much more advanced than that of restriction enzymes. ZFN monomers are molecular proteins with two functional fused domains including the C2H2 zinc-finger (ZF) DNA-binding domain, which targets three base pairs and a non-specific catalytic domain of the FokI endonuclease. The C2H2 ZF domain is consisting of about 30 amino acids, two antiparallel β-sheets and an α-helix, and a zinc ion coordinated by two cysteine residues in the β-sheets and two histidine residues in the α-helix. FokI is a type IIS restriction enzyme involved in cleaving DNA at a distinct distance away from their recognition sites. To generate three-finger ZFs recognizing a 9-bp sequence in modular assembly, the user joins the appropriate ZF modules together. A DNA double-stranded cleavage requires dimerization of two FokI nuclease domains [30,31][30][31]. Although ZFN method was applied to gene editing in human cells and model organisms including Arabidopsis thaliana, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Drosophila, there have not been any studies done in fungi.

2.4. Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs)

TALENs have emerged as an alternative genome editing tool to ZFNs and are similar to ZFNs in that they can cleave their double-stranded DNA target at any desired site. Fok1 nuclease is a common functional part between ZFNs and TALENs. However, designing TALENs is more straightforward than ZNFs. In TALEN-mediated gene editing process, TALEs bind their DNA at the desired site by arrays of highly conserved 33–35 amino acid repeats that are flanked by additional TALE-derived domains at the amino-terminal and carboxy-terminal ends of the array. Each TALE repeat is largely identical, except for two highly variable residues typically found at positions 12 and 13 of the domain, referred to as the repeat variable di-residues (RVDs). This structural difference has increased the detection coefficient in TALENs and has shown higher target binding specificity as compared to ZFNs. Thus, TALENs have the ability to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [32,33][32][33].

2.5. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-CRISPR Associated Protein 9 (CRISPR-Cas9)

The CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) is an adaptive immunity system in bacteria and was initially used for genome editing in mammalian and yeast cells [34,35,36][34][35][36]. Gradually it has become a revolutionary tool in molecular biology and biotechnology that enables us to perform precise genomic, epigenomic, RNA editing, gene expression regulation, nucleic acid detection, and several applications in a wide variety of organisms [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44]. Currently, delivery of the CRISPR system’s components into fungal cells through different types of vectors and assembled purified sgRNA/Cas9 complexes have enabled us to mutate the genome or alter gene expression regulation in dozens of fungal species [36,45,46,47,48][36][45][46][47][48]. Alternatively, cell-penetrating peptides have been shown to be able to enter into Candida spp. [49,50][49][50]. These CRISPR-empowered enhancements have been considered a scientific breakthrough in fungal molecular biology and biotechnology [51], and stem from its versatile potential to functional characterization and breeding of clinically and industrially important fungi.

(References would be added automatically after the entry is online)

References

- Lin, X.; Alspaugh, J.A.; Liu, H.; Harris, S. Fungal Morphogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 5, a019679.

- Schmiedel, Y.; Zimmerli, S. Common invasive fungal diseases: An overview of invasive candidiasis, aspergillosis, cryptococcosis and Pneumocystis pneumonia. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2016, 146, 14281.

- Ramana, K.V.; Kandi, S.P.V.B.; Sharada, C.V.; Rao, R.; Mani, R.; Rao, S.D. Invasive Fungal Infections: A Comprehensive Review. Am. J. Infect. Dis. Microbiol. 2013, 1, 64–69.

- Wang, Q.; Zhong, C.; Xiao, H. Genetic Engineering of Filamentous Fungi for Efficient Protein Expression and Secretion. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 293.

- Hittinger, C.T.; Alexander, W.G. Constructs and Methods for Genome Editing and Genetic Engineering of Fungi and Protists. U.S. Patent 9879270, 30 January 2018.

- Perez-Nadales, E.; Nogueira, M.F.A.; Baldin, C.; Castanheira, S.; El Ghalid, M.; Grund, E.; Lengeler, K.; Marchegiani, E.; Mehrotra, P.V.; Moretti, M.; et al. Fungal model systems and the elucidation of pathogenicity determinants. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014, 70, 42–67.

- Dudakova, A.; Spiess, B.; Tangwattanachuleeporn, M.; Sasse, C.; Buchheidt, D.; Weig, M.; Groß, U.; Bader, O. Molecular Tools for the Detection and Deduction of Azole Antifungal Drug Resistance Phenotypes in Aspergillus Species. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 1065–1091.

- Gaj, T.; Sirk, S.J.; Shui, S.-L.; Liu, J. Genome-Editing Technologies: Principles and Applications. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a023754.

- Hilton, I.B.; Gersbach, C.A. Enabling functional genomics with genome engineering. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1442–1455.

- Chang, S.-S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. RNA Interference Pathways in Fungi: Mechanisms and Functions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 66, 305–323.

- Lax, C.; Tahiri, G.; Patiño-Medina, J.A.; Cánovas-Márquez, J.T.; Pérez-Ruiz, J.A.; Osorio-Concepción, M.; Navarro, E.; Calo, S. The Evolutionary Significance of RNAi in the Fungal Kingdom. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9348.

- Mousavi, B.; Hedayati, M.T.; Teimoori-Toolabi, L.; Guillot, J.; Alizadeh, A.; Badali, H. cyp51A gene silencing using RNA interference in azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus. Mycoses 2015, 58, 699–706.

- Martel, C.M.; Parker, J.E.; Bader, O.; Weig, M.; Gross, U.; Warrilow, A.G.S.; Kelly, D.E.; Kelly, S.L. A Clinical Isolate of Candida albicans with Mutations in ERG11 (Encoding Sterol 14α-Demethylase) and ERG5 (Encoding C22 Desaturase) is Cross Resistant to Azoles and Amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 3578–3583.

- Sanglard, D.; Ischer, F.; Parkinson, T.; Falconer, D.; Bille, J. Candida albicans Mutations in the Ergosterol Biosynthetic Pathway and Resistance to Several Antifungal Agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2404–2412.

- Zhou, Y.; Liao, M.; Zhu, C.; Hu, Y.; Tong, T.; Peng, X.; Li, M.; Feng, M.; Cheng, L.; Ren, B.; et al. ERG3 and ERG11 genes are critical for the pathogenesis of Candida albicans during the oral mucosal infection. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 10, 1–8.

- Chang, Z.; Yadav, V.; Lee, S.C.; Heitman, J. Epigenetic mechanisms of drug resistance in fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2019, 132, 103253.

- Poças-Fonseca, M.J.; Cabral, C.G.; Manfrão-Netto, J.H.C. Epigenetic manipulation of filamentous fungi for biotechnological applications: A systematic review. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 885–904.

- Brandão, F.; Esher, S.K.; Ost, K.S.; Pianalto, K.; Nichols, C.B.; Fernandes, L.; Bocca, A.L.; Poças-Fonseca, M.J.; Alspaugh, J.A. HDAC genes play distinct and redundant roles in Cryptococcus neoformans virulence. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–17.

- Brandão, F.A.; Derengowski, L.S.; Albuquerque, P.; Nicola, A.M.; Silva-Pereira, I.; Poças-Fonseca, M.J. Histone deacetylases inhibitors effects on Cryptococcus neoformans major virulence phenotypes. Virulence 2015, 6, 618–630.

- Elbashir, S.M.; Harborth, J.; Weber, K.; Tuschl, T. Analysis of gene function in somatic mammalian cells using small interfering RNAs. Methods 2002, 26, 199–213.

- Martinez, J.; Patkaniowska, A.; Elbashir, S.M.; Harborth, J.; Hossbach, M.; Urlaub, H.; Meyer, J.; Weber, K.; VanDenburgh, K.; Manninga, H.; et al. Analysis of mammalian gene function using small interfering RNAs. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 2003, 3, 333.

- Alic, N.; Hoddinott, M.P.; Foley, A.; Slack, C.; Piper, M.D.W.; Partridge, L. Detrimental Effects of RNAi: A Cautionary Note on its use in Drosophila Ageing Studies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45367.

- Roberts, R.J.; Murray, K. Restriction Endonuclease. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 1976, 4, 123–164.

- Brown, D.H.; Slobodkin, I.V.; Kumamoto, C.A. Stable transformation and regulated expression of an inducible reporter construct in Candida albicans using restriction enzyme-mediated integration. Mol. Genet. Genom. 1996, 251, 75–80.

- Brown, J.S.; Aufauvre-Brown, A.; Holden, D.W. Insertional mutagenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol. Genet. Genom. 1998, 259, 327–335.

- Warrilow, A.G.S.; Parker, J.E.; Price, C.L.; Nes, W.D.; Kelly, S.L.; Kelly, D.E. In Vitro Biochemical Study of CYP51-Mediated Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 7771–7778.

- Jiang, C.; Dong, D.; Yu, B.; Cai, G.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y.; Peng, Y. Mechanisms of azole resistance in 52 clinical isolates of Candida tropicalis in China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 68, 778–785.

- Lartigue, C.; Vashee, S.; Algire, M.A.; Chuang, R.-Y.; Benders, G.A.; Ma, L.; Noskov, V.N.; Denisova, E.A.; Gibson, D.G.; Assad-Garcia, N.; et al. Creating Bacterial Strains from Genomes that Have Been Cloned and Engineered in Yeast. Science 2009, 325, 1693–1696.

- Kim, Y.G.; Cha, J.; Chandrasegaran, S. Hybrid restriction enzymes: Zinc finger fusions to Fok I cleavage domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 1156.

- Urnov, F.D.; Rebar, E.J.; Holmes, M.C.; Zhang, H.S.; Gregory, P.D. Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 636–646.

- Carroll, D. Genome engineering with zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics 2011, 188, 773–782.

- Joung, J.K.; Sander, J.D. TALENs: A widely applicable technology for targeted genome editing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 49–55.

- Gaj, T.; Gersbach, C.A.; Barbas, C.F. Zfn, Talen and Crispr/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 397–405.

- Cong, L.; Ran, F.A.; Cox, D.; Lin, S.; Barretto, R.; Habib, N.; Hsu, P.D.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Marraffini, L.A.; et al. Multiplex Genome Engineering using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science 2013, 339, 819–823.

- Mali, P.; Yang, L.; Esvelt, K.M.; Aach, J.; Guell, M.; DiCarlo, J.E.; Norville, J.E.; Church, G.M. RNA-Guided Human Genome Engineering via Cas9. Science 2013, 339, 823–826.

- Dicarlo, J.E.; Norville, J.E.; Mali, P.; Rios, X.; Aach, J.; Church, G.M. Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 4336–4343.

- Kennedy, E.M.; Bassit, L.C.; Mueller, H.; Kornepati, A.V.; Bogerd, H.P.; Nie, T.; Chatterjee, P.; Javanbakht, H.; Schinazi, R.F.; Cullen, B.R. Suppression of hepatitis B virus DNA accumulation in chronically infected cells using a bacterial CRISPR/Cas RNA-guided DNA endonuclease. Virology 2015, 476, 196–205.

- Ran, F.A.; Hsu, P.D.; Wright, J.; Agarwala, V.; Scott, D.A.; Zhang, F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 2281–2308.

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, G. CRISPR/Cas Systems towards Next-Generation Biosensing. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 730–743.

- Wang, J.; Lu, A.; Bei, J.; Zhao, G.; Wang, J. CRISPR/ddCas12a-based programmable and accurate gene regulation. Cell Discov. 2019, 5, 15.

- Vercoe, R.B.; Chang, J.T.; Dy, R.L.; Taylor, C.; Gristwood, T.; Clulow, J.S.; Richter, C.; Przybilski, R.; Pitman, A.R.; Fineran, P.C. Cytotoxic Chromosomal Targeting by CRISPR/Cas Systems Can Reshape Bacterial Genomes and Expel or Remodel Pathogenicity Islands. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003454.

- Farboud, B.; Jarvis, E.; Roth, T.L.; Shin, J.; Corn, J.E.; Marson, A.; Meyer, B.J.; Patel, N.H.; Hochstrasser, M.L. Enhanced Genome Editing with Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein in Diverse Cells and Organisms. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 135, e57350.

- Rahimi, H.; Salehiabar, M.; Barsbay, M.; Ghaffarlou, M.; Kavetskyy, T.; Sharafi, A.; Davaran, S.; Chauhan, S.C.; Danafar, H.; Kaboli, S.; et al. Crispr Systems for COVID-19 Diagnosis. ACS Sensors 2021.

- Sasano, Y.; Nagasawa, K.; Kaboli, S.; Sugiyama, M.; Harashima, S. CRISPR-PCS: A powerful new approach to inducing multiple chromosome splitting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–11.

- Kuivanen, J.; Wang, Y.-M.J.; Richard, P. Engineering Aspergillus niger for galactaric acid production: Elimination of galactaric acid catabolism by using RNA sequencing and CRISPR/Cas9. Microb. Cell Fact. 2016, 15, 1–9.

- Umeyama, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Shimosaka, H.; Inukai, T.; Yamagoe, S.; Takatsuka, S.; Hoshino, Y.; Nagi, M.; Nakamura, S.; Kamei, K.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing to Demonstrate the Contribution of Cyp51A Gly138Ser to Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62.

- Gu, Y.; Gao, J.; Cao, M.; Dong, C.; Lian, J.; Huang, L.; Cai, J.; Xu, Z. Construction of a series of episomal plasmids and their application in the development of an efficient CRISPR/Cas9 system in Pichia pastoris. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 79.

- Al Abdallah, Q.; Ge, W.; Fortwendel, J.R. A Simple and Universal System for Gene Manipulation in Aspergillus fumigatus: In Vitro-Assembled Cas9-Guide RNA Ribonucleoproteins Coupled with Microhomology Repair Templates. Msphere 2017, 2, e00446.

- Gong, Z.; Karlsson, A.J. Translocation of cell-penetrating peptides into Candida fungal pathogens. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 1714–1725.

- Farkhani, S.M.; Valizadeh, A.; Karami, H.; Mohammadi, S.; Sohrabi, N.; Badrzadeh, F. Cell penetrating peptides: Efficient vectors for delivery of nanoparticles, nanocarriers, therapeutic and diagnostic molecules. Peptides 2014, 57, 78–94.

- Idnurm, A.; Meyer, V. The CRISPR revolution in fungal biology and biotechnology, and beyond. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2018, 5, 19.