Raf kinase inhibitory protein (RKIP), also known as a phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 (PEBP1), functions as a tumor suppressor and regulates several signaling pathways, including ERK and NF-κκB. RKIP is severely downregulated in human malignant cancers, indicating a functional association with cancer metastasis and poor prognosis. The transcription regulation of RKIP gene in human cancers is not well understood. In this study, we suggested a possible transcription mechanism for the regulation of RKIP in human cancer cells. We found that Metadherin (MTDH) significantly repressed the transcriptional activity of RKIP gene.

- RKIP/PEBP1

- MTDH/AEG-1

- VEZF1

- transcription factor

- RKIP expression

- ChIP assay

- promoter assay

1. Introduction

Raf Kinase Inhibitory Protein (RKIP; also called PEBP1) was first elucidated as a binding protein of Raf1, a key regulator in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways. RKIP is ubiquitous in cellular structures, including cytoplasm, inner periplasmic membrane, and others

[1]

. Low expression of RKIP protein has been reported in many human cancers, including metastatic prostate, breast, and colon cancers, hepatocellular carcinoma, melanomas, and insulinomas

[2]

. Thus, lack of RKIP protein activates the MEK/ERK pathway, consequently promoting cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and migration during cancer progression

. As a result, RKIP is considered a diagnostic biomarker associated with cancer metastasis and poor prognosis. However, the mechanism responsible for the low expression of RKIP in human cancers is not well understood. One possible mechanism for the low intracellular level of RKIP in human diseases could involve reducing the RKIP gene transcription. To test this possibility, we investigated transcription factors and co-factors that directly or indirectly regulate the expression of the RKIP gene.

The oncogene Metadherin (MTDH, also known as astrocyte elevated gene 1, AEG1) was first identified as a novel transcript in the primary human fetal astrocytes (PHFAs) infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 and is specifically elevated in astrocytes[6]. MTDH is generally localized in the nucleus and cytoplasm as well as at the plasma membrane and is functionally associated with several oncogenic signaling pathways, such as PI3K/AKT pathway, and transcription factors, such as nuclear factor NF-κB. Many studies show that MTDH is overexpressed in all solid tumors, including breast, prostate, gastric, renal, colorectal, ovarian, and endometrial cancers[7][8][9]. A study suggests that MTDH could modulate gene expression by acting as a co-factor through its nuclear homing domain, as it does not contain any domains necessary for the direct DNA binding [10]. In this study, we examined whether MTDH plays a critical role in regulating RKIP expression as a transcription co-factor. We found that MTDH associates with the RKIP promoter and significantly inhibits the expression of RKIP. This suggests that MTDH negatively regulates the transcription of the RKIP gene, which could be a target for the development of new cancer therapy.

2. MTDH Is Upregulated In Cancer Tissues With Low Frequency Of Genetic Alterations

MTDH is broadly found in the nucleus or the cytoplasm of different types of malignant cells

2. MTDH Is Upregulated In Cancer Tissues With Low Frequency Of Genetic Alterations

MTDH is broadly found in the nucleus or the cytoplasm of different types of malignant cells

[11]

. Its expression is specifically regulated by nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and it is also highly related to tumor progression, such as metastasis and angiogenesis. In addition, the high expression of MTDH is connected to the aggressive metastasis in breast, ovarian, and cervical cancers

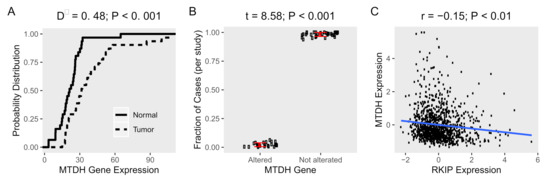

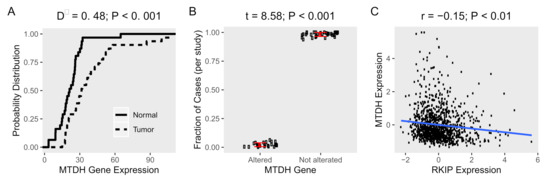

. First, we examined the expression profile of MTDH in cancer tissues (n = 31) obtained from human samples in the cancer genome atlas (TCGA), and the corresponding normal tissues from GEPIA

[13]. We found that the expression of MTDH was significantly higher in tumor tissues compared to control tissues (Figure 1A). More specifically, the percentage of tumor tissues at every expression level was higher than normal tissues, as demonstrated by empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDF). Since genetic changes exert a great influence on not only gene expression but also gene function, we investigated the genetic alterations (mutation, fusion, amplification, or deletion) of the MTDH gene obtained from human subjects (n = 10,953) in the same set of the TCGA cancer studies. We found that few cancer tissue samples had any genetic alterations (2% of cases) of the MTDH gene (Figure 1B). Our data indicate that MTDH was highly expressed in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues along with a lower frequency of genetic alterations of the MTDH gene.

Figure 1. Expression and alterations of MTDH gene in cancer tissues. Gene expression data of human samples and matched normal tissues (n = 31) were obtained from TCGA and GEPIA, respectively. (A) Empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDF) of expression of MTDH in cancer (dot line) and normal tissues (solid line) were calculated. The maximum distance (D−) between the curves was calculated using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. (B) The average fraction of cases (n = 10,953) with or without alterations (mutation, fusion, amplification, or deletion of the MTDH gene in cancer tissues (n = 31) from TCGA. The difference between altered and not altered were tested using t-test. (C) A scatter plot of the MTDH and RKIP expression in patient tissue (n = 1084) from TCGA, Breast Cancer cohort. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to evaluate the correlation between the two genes and test for association.

3. MTDH Knockdown Induces RKIP Expression in Breast Cancer Cell Lines

In general, RKIP, known as a tumor and metastasis suppressor, is severely downregulated in metastatic breast tissue compared to normal tissue

. We found that the expression of MTDH was significantly higher in tumor tissues compared to control tissues (Figure 1A). More specifically, the percentage of tumor tissues at every expression level was higher than normal tissues, as demonstrated by empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDF). Since genetic changes exert a great influence on not only gene expression but also gene function, we investigated the genetic alterations (mutation, fusion, amplification, or deletion) of the MTDH gene obtained from human subjects (n = 10,953) in the same set of the TCGA cancer studies. We found that few cancer tissue samples had any genetic alterations (2% of cases) of the MTDH gene (Figure 1B). Our data indicate that MTDH was highly expressed in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues along with a lower frequency of genetic alterations of the MTDH gene.

Figure 1. Expression and alterations of MTDH gene in cancer tissues. Gene expression data of human samples and matched normal tissues (n = 31) were obtained from TCGA and GEPIA, respectively. (A) Empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDF) of expression of MTDH in cancer (dot line) and normal tissues (solid line) were calculated. The maximum distance (D−) between the curves was calculated using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. (B) The average fraction of cases (n = 10,953) with or without alterations (mutation, fusion, amplification, or deletion of the MTDH gene in cancer tissues (n = 31) from TCGA. The difference between altered and not altered were tested using t-test. (C) A scatter plot of the MTDH and RKIP expression in patient tissue (n = 1084) from TCGA, Breast Cancer cohort. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to evaluate the correlation between the two genes and test for association.

3. MTDH Knockdown Induces RKIP Expression in Breast Cancer Cell Lines

In general, RKIP, known as a tumor and metastasis suppressor, is severely downregulated in metastatic breast tissue compared to normal tissue

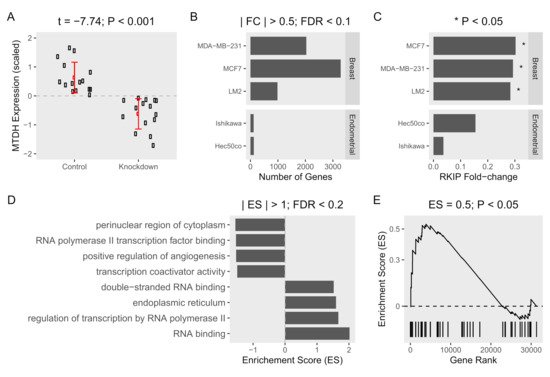

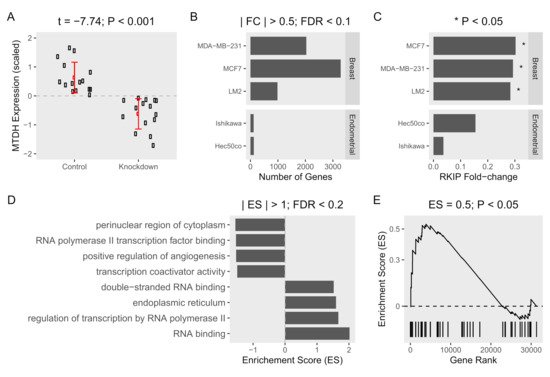

[14]. This is in contrast to MTDH on cancer tissue. To further examine the association of MTDH with RKIP expression in tumor cells, we then performed a systemic analysis using public-access datasets where the MTDH gene was knocked down (Table 1). As expected, the relative expression of MTDH in three breast and two endometrial cancer cell lines was lower in the knockdown condition compared to normal control (Figure 2A). When compared to the control cells, ablation of MTDH caused significant fold-changes in expression of many genes. Indeed, we observed that about 1000–3000 genes were differentially expressed in breast cancer cells when the MTDH gene was knocked down, but few genes were altered in endometrial cells according to the knockdown of MTDH (Figure 2B). Changes in gene expression were shown more clearly in breast cancer cells than endometrial cells, especially in MCF-7. In the same dataset, RKIP expression was found to be highly affected by the reduction of MTDH. In fact, knockdown of the MTDH gene resulted in a 0.3-fold increase in RKIP expression (p-value < 0.05) in the three MTDH-knockdown breast cells compared to controls (Figure 2C). Additionally, we found an inverse correlation of MTDH and RKIP expression (Figure 1C) in patient breast cancer cohort from TCGA. Due to the converse expressions of RKIP and MTDH in our data, it is important to determine the molecular mechanism of the correlation between the two proteins in order to understand the regulation of cancer progression.

Figure 2. Gene expression and gene set enrichment analysis of MTDH-knockdown in cancer cell lines. Datasets obtained from three MTDH-knockdown breast cells (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and LM2) and two MTDH-knockdown endometrial (Ishikawa, and Hec50co) cancer cell lines were compared to control cells (three samples of each cell line). (A) Expression of MTDH (scaled fold-change (log2)) in five knockdown breast and endometrial cancer cell lines and corresponding five control cells. The mean difference in expression was tested using t-test. (B) Gene expression was compared between knockdown and control cells in each cell line. Fold-change (FC) was calculated and tested for significance using false-discovery rate (FDR). (C) Fold-changes of RKIP in each cell line are shown. (D) Genes were ranked based on fold-change from the most positively changed to the most negatively changed in knockdown vs. control cells. Enrichment of MTDH-related gene ontology terms was calculated as the over-representation of the term members in the top or the bottom of the ranked list of differentially expressed genes in one or more breast cancer cell lines. Enrichment scores (ES) > 1 and FDR < 0.2 are shown. (E) Enrichment of the “negative regulation of autophagy” term.

Besides, we examined the enrichment of MTDH-related gene ontology terms among differentially expressed genes in MTDH-knockdown vs. control cells. Generally, the elevated level of MTDH in cancer cells is considered a hallmark for the severity of tumor progression. Several biological functions related to MTDH were enriched in the MTDH knockdown (Figure 2D). A positive enrichment score means that the gene numbers at a given term are over-represented in the upregulated genes as a result of MTDH knockdown. The reverse is true for negative enrichment scores and downregulated genes. As expected, gene products in terms related to tumor progression such as positive regulation of angiogenesis were dysregulated in the absence of MTDH. RNA polymerase II transcription factor binding and transcription coactivator binding terms were over-represented between the two experimental groups. Besides, genes in regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II term were downregulated by MTDH knockdown. This strongly indicates a role for MTDH in regulating gene transcription and expression. We additionally found that MTDH-knockdown induced significant changes in enrichment of the “negative regulation of autophagy” gene term in the same datasets (Figure 2E). Interestingly, RKIP was suggested to be a negative regulator of autophagy process in our recent study

. This is in contrast to MTDH on cancer tissue. To further examine the association of MTDH with RKIP expression in tumor cells, we then performed a systemic analysis using public-access datasets where the MTDH gene was knocked down (Table 1). As expected, the relative expression of MTDH in three breast and two endometrial cancer cell lines was lower in the knockdown condition compared to normal control (Figure 2A). When compared to the control cells, ablation of MTDH caused significant fold-changes in expression of many genes. Indeed, we observed that about 1000–3000 genes were differentially expressed in breast cancer cells when the MTDH gene was knocked down, but few genes were altered in endometrial cells according to the knockdown of MTDH (Figure 2B). Changes in gene expression were shown more clearly in breast cancer cells than endometrial cells, especially in MCF-7. In the same dataset, RKIP expression was found to be highly affected by the reduction of MTDH. In fact, knockdown of the MTDH gene resulted in a 0.3-fold increase in RKIP expression (p-value < 0.05) in the three MTDH-knockdown breast cells compared to controls (Figure 2C). Additionally, we found an inverse correlation of MTDH and RKIP expression (Figure 1C) in patient breast cancer cohort from TCGA. Due to the converse expressions of RKIP and MTDH in our data, it is important to determine the molecular mechanism of the correlation between the two proteins in order to understand the regulation of cancer progression.

Figure 2. Gene expression and gene set enrichment analysis of MTDH-knockdown in cancer cell lines. Datasets obtained from three MTDH-knockdown breast cells (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and LM2) and two MTDH-knockdown endometrial (Ishikawa, and Hec50co) cancer cell lines were compared to control cells (three samples of each cell line). (A) Expression of MTDH (scaled fold-change (log2)) in five knockdown breast and endometrial cancer cell lines and corresponding five control cells. The mean difference in expression was tested using t-test. (B) Gene expression was compared between knockdown and control cells in each cell line. Fold-change (FC) was calculated and tested for significance using false-discovery rate (FDR). (C) Fold-changes of RKIP in each cell line are shown. (D) Genes were ranked based on fold-change from the most positively changed to the most negatively changed in knockdown vs. control cells. Enrichment of MTDH-related gene ontology terms was calculated as the over-representation of the term members in the top or the bottom of the ranked list of differentially expressed genes in one or more breast cancer cell lines. Enrichment scores (ES) > 1 and FDR < 0.2 are shown. (E) Enrichment of the “negative regulation of autophagy” term.

Besides, we examined the enrichment of MTDH-related gene ontology terms among differentially expressed genes in MTDH-knockdown vs. control cells. Generally, the elevated level of MTDH in cancer cells is considered a hallmark for the severity of tumor progression. Several biological functions related to MTDH were enriched in the MTDH knockdown (Figure 2D). A positive enrichment score means that the gene numbers at a given term are over-represented in the upregulated genes as a result of MTDH knockdown. The reverse is true for negative enrichment scores and downregulated genes. As expected, gene products in terms related to tumor progression such as positive regulation of angiogenesis were dysregulated in the absence of MTDH. RNA polymerase II transcription factor binding and transcription coactivator binding terms were over-represented between the two experimental groups. Besides, genes in regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II term were downregulated by MTDH knockdown. This strongly indicates a role for MTDH in regulating gene transcription and expression. We additionally found that MTDH-knockdown induced significant changes in enrichment of the “negative regulation of autophagy” gene term in the same datasets (Figure 2E). Interestingly, RKIP was suggested to be a negative regulator of autophagy process in our recent study

[15]. Taken together, our analysis suggests that the expression of MTDH and RKIP are conversely correlated, and that the MTDH gene is functionally related to expression of many genes including RKIP in different oncogenic pathways.

. Taken together, our analysis suggests that the expression of MTDH and RKIP are conversely correlated, and that the MTDH gene is functionally related to expression of many genes including RKIP in different oncogenic pathways.

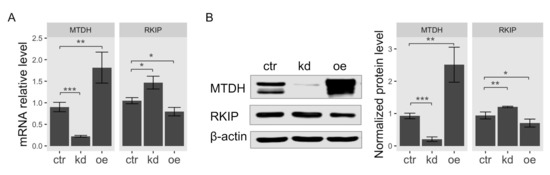

4. MTDH Regulates the Transcription of the RKIP Gene

According to the result of gene expression analysis in Figure 1, the observed expression level of RKIP was the most significantly upregulated in breast cancer cell line MCF-7 among MTDH-knockdown cells. Therefore, we used MCF-7 cells for further investigation in this study. To determine the functional association of MTDH with RKIP, we examined both mRNA and protein levels in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells when the MTDH gene was knocked down or overexpressed. First, we examined total RKIP mRNA levels in MTDH-knockdown and MTDH-overexpressing MCF-7 cancer cells using quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Total RKIP transcripts significantly increased when the MTDH gene was knocked down but reversely decreased in the overexpression of MTDH (Figure 3A). To verify the interaction between MTDH and RKIP indicated by the results of qRT-PCR and microarrays analyses, we examined RKIP protein levels by Western blotting. We found that the protein level of RKIP was specifically regulated by modulating MTDH expression (Figure 3B). Knockdown of MTDH resulted in a significant increase of RKIP protein level compared to control. By contrast, MTDH overexpression relatively decreased the level of RKIP protein, indicating that the intracellular level of RKIP is somehow regulated by MTDH. Collectively, we suggest that MTDH could be a transcriptional repressor of the RKIP gene.

4. MTDH Regulates the Transcription of the RKIP Gene

According to the result of gene expression analysis in Figure 1, the observed expression level of RKIP was the most significantly upregulated in breast cancer cell line MCF-7 among MTDH-knockdown cells. Therefore, we used MCF-7 cells for further investigation in this study. To determine the functional association of MTDH with RKIP, we examined both mRNA and protein levels in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells when the MTDH gene was knocked down or overexpressed. First, we examined total RKIP mRNA levels in MTDH-knockdown and MTDH-overexpressing MCF-7 cancer cells using quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Total RKIP transcripts significantly increased when the MTDH gene was knocked down but reversely decreased in the overexpression of MTDH (Figure 3A). To verify the interaction between MTDH and RKIP indicated by the results of qRT-PCR and microarrays analyses, we examined RKIP protein levels by Western blotting. We found that the protein level of RKIP was specifically regulated by modulating MTDH expression (Figure 3B). Knockdown of MTDH resulted in a significant increase of RKIP protein level compared to control. By contrast, MTDH overexpression relatively decreased the level of RKIP protein, indicating that the intracellular level of RKIP is somehow regulated by MTDH. Collectively, we suggest that MTDH could be a transcriptional repressor of the RKIP gene.

Figure 3.

Transcriptional activation of

RKIP

gene in

MTDH

-knockdown or -overexpressing cells. Lentiviral vector with

shMTDH

sequence and FLAG-MTDH plasmid were used for generating knockdown and overexpression in MCF-7 cells, respectively. (

A

) qRT-PCR analysis. The relative mRNA transcripts of MTDH or RKIP in

MTDH

-knockdown cells (

kd

),

MTDH

-overexpressing cells (

oe

), or control cells (

ctr

) were determined by qPCR analysis. The relative levels were normalized to the level of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Data represent the means ± S.D of the PCR reactions in triplicate. (

B

) Western blot analysis for RKIP expression. Total cellular proteins extracted from either

MTDH

-knockdown cells (

kd

) or

MTDH

-overexpressing cells (

oe

) were subjected to Western blotting analysis (

left

) using antibodies against MTDH or RKIP. The relative expression of each protein normalized to

β

-actin (an internal control). Data indicate the mean value ± S.D of at least three independent experiments. *** <0.005,** <0.01, * <0.05

p

-value.

5. MTDH Binds to the RKIP Promoter

5. MTDH Binds to the RKIP Promoter

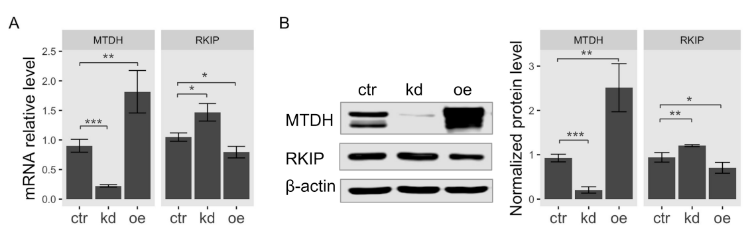

We determined whether MTDH binds to the RKIP promoter using the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis. Since MTDH contains no DNA-binding domain as previously described [10], we used a dual cross-linking ChIP method that allows effective transcription co-factors linking to DNA. The targeted regions on the RKIP promoter (251 bp, from −83 to +168) for ChIP analysis are represented in Figure 4A. The ChIP assay using anti-MTDH antibodies showed that MTDH was physically linked to the RKIP promoter region, but not in the case of using negative IgG (Figure 4A). Interestingly, when we used the conventional ChIP assay by a single cross-linking DNA-protein step with 4% formaldehyde, we were unable to detect any association of MTDH with the RKIP promoter (Figure S1). These results suggest that MTDH could be a transcriptional repressor that inhibits the transcription of RKIP. This repression could occur via an indirect association with other transcription factors that bind to a nearby region of the RKIP transcription start site.

To further confirm these results, we performed the luciferase reporter assay using the RKIP promoter. First, we constructed reporter vectors containing serial deletions of the RKIP promoter DNA (−806 to +168; −428 to +168; −83 to +168; −48 to +168; and +1 to +168) linked to the firefly luciferase gene (pGL4.20 vector), as shown in (Figure 4B). Then, we tested the RKIP promoter activity using these constructs in MCF-7 cells. Interestingly, deleting the upstream region of RKIP promoter up to −83 caused a gradual increase in the promoter activity. The promoter region of −83/+168 was the most active. However, further deletions of the RKIP promoter (either −48/+168 or +1/+168) led to a significant decrease in the promoter activity (Figure 4C). Similar results were observed by Zhang etet al. al. [16].

To test how MTDH influences the RKIP RKIP promoter activity, we measured the luciferase activity upon perturbing MTDH expression (either knockdown or overexpression). The promoter construct −83/+168 showed the highest activity in the assay. As expected, the RKIP promoter activity highly increased in MTDH-knockdown MCF-7 cells compared to control cells. Conversely, the promoter activity dramatically decreased in MTDH-overexpressing MCF-7 cells (Figure 4D). In addition to MTDH-dependent regulation of RKIP expression, the overexpression of vascular endothelial zinc finger 1 (VEZF1), a transcription factor, slightly inhibited the RKIP promoter activity. VEZF1 has been suggested as a functional partner of RKIP according to our previous study[17]. Accordingly these results indicate that MTDH plays an important role in the transcriptional regulation of RKIP gene through either direct or indirect binding with other factors to the RKIP promoter region.

Figure 4. MTDH binding to the RKIP promoter. (A) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. MCF-7 cells were double cross-linked with DSG and 4% formaldehyde and lysed with sonication. DNA fragments were immunoprecipitated with anti-MTDH antibodies (MTDH) or IgG as a negative control (IgG). Specific DNA fragments were amplified with a pair of primers. For input control, either none or purified DNA fragments were amplified. PCR primers used for ChIP assay were created to specifically amplify a 256 bp-DNA fragment (from −83 to +168 on the upstream region of RKIP gene, as shown in the top of (A). Amplified DNA fragments were separated on a 1% agarose gel and visualized by EtBr staining. The first lane indicates 100 bp size markers. (B) A schematic illustration of the constructs for the luciferase RKIP promoter assay. The serially deleted RKIP promoter DNA fragments (−806/+168, −428/+168, −83/+169, −48/+168, and +/+168) were inserted into the pGL4.20 luciferase vector. (C) The RKIP promoter activity. The relative luciferase activities were determined in MCF-7 cells transfected with serially deleted constructs of the RKIP promoter. Data represent fold-changes from three independent experiments. ** <0.01, * <0.05 p-value. (D) RKIP promoter activity upon modulating MTDH expression. MCF-7 cells were transfected by none (ctr), shMTDH (kdMTDH), FLAG-MTDH (oeMTDH), or VEZF1 plasmids (oeVEZF1) and used in luciferase assay with the RKIP promoter −83/+168 construct. Data represent fold changes from five independent experiments. ** <0.01, * <0.05 p-value.

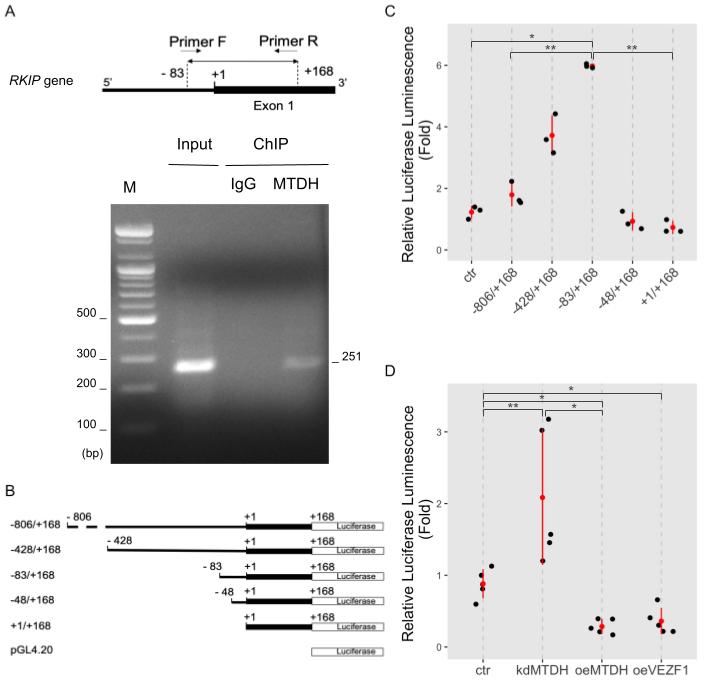

6. Functional Association between MTDH and VEZF1 during Transcriptional Activation of RKIP Gene

As mentioned above, MTDH could not directly bind to the RKIP promoter region. Instead, it might require other transcription factors to regulate RKIP gene. According to our recent work using weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), RKIP transcripts were functionally associated with the transcription factor VEZF1. In particular, their expression is inversely correlated with each other[17], which is a similar pattern to the RKIP and MTDH association shown above (Figures 2 and 3). Thus, MTDH-dependent transcriptional inhibition of the RKIP gene could require the functional connection with VEZF1. To test this possible mechanism, we first examined the binding ability of VEZF1 to the RKIP promoter region using ChIP assay. As expected, the VEZF1 protein bound to the RKIP promoter (Figure 5A), and the overexpression of VEZF1 strongly inhibited the transcriptional activity of the RKIP gene in the luciferase reporter assay. The activity of the −83/+168 RKIP promoter construct (last bar in Figure 4D) was very similar to the transcriptional activity exhibited in cells overexpressing MTDH. These data suggest that the transcription factor VEZF1 and MTDH could form a DNA-binding complex and subsequently repress RKIP gene expression in cancer cells.

We further examined how the two proteins MTDH and VEZF1 influence the transcriptional activation of RKIP gene using quantitative PCR analysis in cells in which the expression of these proteins was perturbed. As expected, knocking down MTDH increased the transcriptional activation of RKIP gene, and overexpressing VEZF1 significantly decreased the RKIP mRNA transcripts (Figure 5B). However, in the case of the double perturbation (MTDH-knockdown and VEZF1-overexpression), the amount of RKIP transcripts was similar to the value obtained from VEZF1-overexpressing cells. This result indicates that MTDH-dependent inhibition of RKIP expression is not observed at the high level of VEZF1 protein.

Figure 5. Functional linkage between VEZF1 and MTDH in RKIP transcription. (A) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay of the RKIP promoter with VEZF1. MCF-7 cells were cross-linked with 4% formaldehyde and lysed with sonication. DNA fragments were immunoprecipitated with anti-VEZF1 antibodies (VEZF1) or IgG as a negative control (IgG), and a specific DNA fragment of 251-bp was amplified with a pair of RKIP primers described in “Materials and Methods”. For input control, the purified DNA fragments were amplified. Amplified DNA fragments were separated on a 1% agarose gel and visualized by EtBr staining. The first lane indicates 100 bp size markers. (B) qRT-PCR analysis. The relative RKIP mRNA transcripts were determined in each condition: control (ctr), MTDH knockdown (kdMTDH), VEZF1 overexpression (kdVEZF1), and MTDH knockdown and VEZF1 overexpression (kdMTDH + oeVEZF1). PCR products amplified by RKIP primers (Figure 3A) were normalized to GAPDH. Data represents the means ± S.D of the PCR reactions in triplicate. ** <0.01 p-value (C) A schematic diagram for the MTDH-dependent inhibition of RKIP transcription. The transcriptional activity of RKIP gene is elevated in low level of MTDH (a), and suppressed in high level of MTDH (b), presumably by blocking the action of RNA polymerase II initiation complex. Factor X indicates an unknown protein. This figure was created with BioRender.com, accessed on 11 February 2021.

7. Conclussion

Based on our recent study, the expression of RKIP gene is functionally connected to the vascular endothelial zinc finger 1 (VEZF1), a transcription factor

7. Conclussion

Based on our recent study, the expression of RKIP gene is functionally connected to the vascular endothelial zinc finger 1 (VEZF1), a transcription factor

[17]

. Therefore, VEZF1 might also be involved in MTDH-dependent regulation of the gene. In this study, we showed that VEZF1 tightly bound to the region −83 to +168 on the RKIP promoter, and it significantly inhibited the promoter activity, similar to MTDH. These observations suggest that direct association of MTDH with VEZF1 or indirect connection with unknown proteins, as shown in Figure 5C, could reduce the transcriptional activity of RKIP gene and control its intracellular protein level in cancer. VEZF1 is highly expressed in endothelial cells, and it is an important regulator for angiogenesis in cancer

. By contrast, RKIP negatively regulates angiogenesis and inhibits cancer invasion and metastasis

[22][23]. Considering these results, VEZF1/MTDH-mediated inverse regulation of the RKIP gene could be a critical mechanism in tumorigenesis. However, we need further experiments to show how the two proteins VEZF1 and MTDH cooperatively regulate the expression of RKIP gene during cancer progression.

In conclusion, MTDH and RKIP proteins are important prognostic markers in human cancers. They exhibited an inverse correlation in expression in malignant cancer cells. MTDH transcriptionally repressed RKIP gene. Thus, perturbing the MTDH–RKIP relation in human cancer might serve as a target developing effective anticancer therapy.

. Considering these results, VEZF1/MTDH-mediated inverse regulation of the RKIP gene could be a critical mechanism in tumorigenesis. However, we need further experiments to show how the two proteins VEZF1 and MTDH cooperatively regulate the expression of RKIP gene during cancer progression.

In conclusion, MTDH and RKIP proteins are important prognostic markers in human cancers. They exhibited an inverse correlation in expression in malignant cancer cells. MTDH transcriptionally repressed RKIP gene. Thus, perturbing the MTDH–RKIP relation in human cancer might serve as a target developing effective anticancer therapy.

References

- Kam Yeung; Thomas Seitz; Shengfeng Li; Petra Janosch; Brian McFerran; Christian Kaiser; Frances Fee; Kostas D. Katsanakis; David W. Rose; Harald Mischak; et al.John M. SedivyWalter Kolch Suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity and MAP kinase signalling by RKIP. Nature 1999, 401, 173-177, 10.1038/43686.

- Devasis Chatterjee; Yin Bai; Zhe Wang; Sandy Beach; Stephanie Mott; Rajat Roy; Corey Braastad; Yaping Sun; Asok Mukhopadhyay; Bharat B. Aggarwal; et al.James DarnowskiPanayotis PantazisJames WycheZheng FuYasuhide KitagwaEvan T. KellerJohn M. SedivyKam C. Yeung RKIP Sensitizes Prostate and Breast Cancer Cells to Drug-induced Apoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 17515-17523, 10.1074/jbc.m313816200.

- Sungdae Park; Miranda L Yeung; Sandy Beach; Janiel M Shields; Kam C Yeung; RKIP downregulates B-Raf kinase activity in melanoma cancer cells. Oncogene 2005, 24, 3535-3540, 10.1038/sj.onc.1208435.

- Sarah F. Funderburk; Bridget K. Marcellino Ba; Zhenyu Yue; Cell “Self-Eating” (Autophagy) Mechanism in Alzheimer's Disease. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine: A Journal of Translational and Personalized Medicine 2010, 77, 59-68, 10.1002/msj.20161.

- Sun Young Kim; RKIP Downregulation Induces the HBx-Mediated Raf-1 Mitochondrial Translocation. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2011, 21, 525-528, 10.4014/jmb.1012.12023.

- Zao-Zhong Su; Dong-Chul Kang; Yinming Chen; Olga Pekarskaya; Wei Chao; David J Volsky; Paul B Fisher; Identification and cloning of human astrocyte genes displaying elevated expression after infection with HIV-1 or exposure to HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein by rapid subtraction hybridization, RaSH. Oncogene 2002, 21, 3592-3602, 10.1038/sj.onc.1205445.

- Guohong Hu; Robert A. Chong; QiFeng Yang; Yong Wei; Mario A. Blanco; Feng Li; Michael Reiss; Jessie L.-S. Au; Bruce G. Haffty; Yibin Kang; et al. MTDH Activation by 8q22 Genomic Gain Promotes Chemoresistance and Metastasis of Poor-Prognosis Breast Cancer. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 9-20, 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.11.013.

- Yajun Liang; Da Fu; Guohong Hu; Metadherin: An emerging key regulator of the malignant progression of multiple cancers. Thoracic Cancer 2011, 2, 143-148, 10.1111/j.1759-7714.2011.00064.x.

- Hongtao Song; Cong Li; Renbo Lu; Yuan Zhang; Jingshu Geng; Expression of Astrocyte Elevated Gene-1. International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer 2010, 20, 1188-1196, 10.1111/igc.0b013e3181ef8e21.

- Samuel A. Lambert; Arttu Jolma; Laura F. Campitelli; Pratyush K. Das; Yimeng Yin; Mihai Albu; Xiaoting Chen; Jussi Taipale; Timothy R. Hughes; Matthew T. Weirauch; et al. The Human Transcription Factors. Cell 2018, 172, 650-665, 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.029.

- Gourav Dhiman; Neha Srivastava; Mehendi Goyal; Emad Rakha; Jennifer Lothion-Roy; Nigel P. Mongan; Regina R. Miftakhova; Svetlana F. Khaiboullina; Albert A. Rizvanov; Manoj Baranwal; et al. Metadherin: A Therapeutic Target in Multiple Cancers. Frontiers in Oncology 2019, 9, 349, 10.3389/fonc.2019.00349.

- Yongbin Hou; Lihua Yu; Yonghua Mi; Jiwang Zhang; Ke Wang; Liyi Hu; Association of MTDH immunohistochemical expression with metastasis and prognosis in female reproduction malignancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 38365, 10.1038/srep38365.

- Zefang Tang; Chenwei Li; Boxi Kang; Ge Gao; Cheng Li; Zemin Zhang; GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Research 2017, 45, W98-W102, 10.1093/nar/gkx247.

- Qiongyan Zou; Haijun Wu; Fenfen Fu; Wenjun Yi; Lei Pei; Meirong Zhou; RKIP suppresses the proliferation and metastasis of breast cancer cell lines through up-regulation of miR-185 targeting HMGA2. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2016, 610, 25-32, 10.1016/j.abb.2016.09.007.

- Hae Sook Noh; Young-Sool Hah; Sahib Zada; Ji Hye Ha; Gyujin Sim; Jin Seok Hwang; Trang Huyen Lai; Huynh Quoc Nguyen; Jae-Yong Park; Hyun Joon Kim; et al.June-Ho ByunJong Ryeal HahmKee Ryeon KangDeok Ryong Kim PEBP1, a RAF kinase inhibitory protein, negatively regulates starvation-induced autophagy by direct interaction with LC3. Autophagy 2016, 12, 2183-2196, 10.1080/15548627.2016.1219013.

- Boyan Zhang; Ou Wang; Jingchao Qin; Shuaishuai Liu; Sheng Sun; Huitu Liu; Jian Kuang; Guohua Jiang; Wei Zhang; cis-Acting Elements and trans-Acting Factors in the Transcriptional Regulation of Raf Kinase Inhibitory Protein Expression. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e83097, 10.1371/journal.pone.0083097.

- Mahmoud Ahmed; Trang Huyen Lai; Sahib Zada; Jin Seok Hwang; Trang Minh Pham; Miyong Yun; Deok Ryong Kim; Functional Linkage of RKIP to the Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition and Autophagy during the Development of Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 273, 10.3390/cancers10080273.

- Marco Bruderer; Mauro Alini; Martin Stoddart; Role of HOXA9 and VEZF1 in Endothelial Biology. Journal of Vascular Research 2013, 50, 265-278, 10.1159/000353287.

- Ming He; QianYi Yang; Allison B. Norvil; David Sherris; Humaira Gowher; Characterization of Small Molecules Inhibiting the Pro-Angiogenic Activity of the Zinc Finger Transcription Factor Vezf1. Molecules 2018, 23, 1615, 10.3390/molecules23071615.

- Hiroki Miyashita; Yasufumi Sato; Metallothionein 1 is a Downstream Target of Vascular Endothelial Zinc Finger 1 (VEZF1) in Endothelial Cells and Participates in the Regulation of Angiogenesis. Endothelium 2005, 12, 163-170, 10.1080/10623320500227101.

- Lama AlAbdi; Ming He; QianYi Yang; Allison B. Norvil; Humaira Gowher; The transcription factor Vezf1 represses the expression of the antiangiogenic factor Cited2 in endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2018, 293, 11109-11118, 10.1074/jbc.ra118.002911.

- Evan T. Keller; Metastasis suppressor genes: a role for raf kinase inhibitor protein (RKIP). Anti-Cancer Drugs 2004, 15, 663-669, 10.1097/01.cad.0000136877.89057.b9.

- Le Feng; Conghui Zhang; Guodong Liu; Fang Wang; RKIP negatively regulates the glucose induced angiogenesis and endothelial-mesenchymal transition in retinal endothelial cells. Experimental Eye Research 2019, 189, 107851, 10.1016/j.exer.2019.107851.

- Le Feng; Conghui Zhang; Guodong Liu; Fang Wang; RKIP negatively regulates the glucose induced angiogenesis and endothelial-mesenchymal transition in retinal endothelial cells. Experimental Eye Research 2019, 189, 107851, 10.1016/j.exer.2019.107851.