Jerez (Sherry) is a well-known wine-producing region located in southern Spain, where world-renowned oenological products such as wines, vinegars, and brandies are produced. There are several factors that provide characteristic physical, chemical, and sensory properties to the oenological products obtained in this Sherry region: the climate in the area with hot summers, mild winters, and with limited rainfall; the raw material used consisting on Palomino Fino, Moscatel, and Pedro Ximénez white grape varieties; the special vinification with fortified wines; and aging techniques such as a dynamic system of biological or oxidative aging.

- Sherry

- wine

- vinegar

- brandy

- aroma

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The winemaking tradition in the agricultural areas within the Jerez (Sherry) region dates far back in time. This is an eminent wine-producing region located in the south of Spain, surrounded by mountains and coastal lands that condition the climate in the area, which together with its particular aging methods, are determinant to attain the highly desirable organoleptic characteristics of its oenological products [1]. Worldwide renowned oenological products such as wines, vinegars, and brandies are the result of this unique combination of factors.

Sherry wines are considered among the most highly appreciated products in the world of oenology [2]. Diversity is undoubtedly one of the distinctive features of Sherry’s identity, where just three grape varieties (Palomino, Moscatel, and Pedro Ximénez) give rise to different wines that clearly differ in terms of color, aroma, flavor, and texture depending on their elaboration process. [3].

Those wines that are subjected exclusively to biological aging—i.e., those which are protected from any direct contact with the air by the natural flor velum—retain their initial color, and display a series of distinctive aromatic and gustatory notes derived from the yeasts that form that essential flor velum [4]. On the other hand, other Sherry wines are aged by oxidative or physicochemical means, in direct contact with the oxygen in the air. These gradually acquire a darker hue, and exhibit more complex aromas and flavors [5].

Furthermore, the type of fermentation, which can be either complete or partial allows the production of highly dry wines (fortified wines) or extraordinarily sweet wines (natural sweet wines). By mixing these two types in different proportions, new wines with varying levels of sweetness (liqueur fortified wines) are also obtained [6,7].

Furthermore, the type of fermentation, which can be either complete or partial allows the production of highly dry wines (fortified wines) or extraordinarily sweet wines (natural sweet wines). By mixing these two types in different proportions, new wines with varying levels of sweetness (liqueur fortified wines) are also obtained [6][7].

With regard to Sherry vinegars, these are obtained from the grapes grown in the local vineyards. The authorized grape varieties for the production of Sherry vinegar are the same that those employed for Sherry wine. The Sherry vinegar production process basically consists in the acetic fermentation of local wines, as a result of the transformation of alcohol in acetic acid by acetic bacteria (Mycoderma aceti) and its subsequent aging in wooden casks. The final product presents a color between old gold and mahogany, with an intense aroma, lightly alcoholic, with notes of wine and wood predominating, and a pleasant taste, despite the acidity, with a long aftertaste [8,9].

With regard to Sherry vinegars, these are obtained from the grapes grown in the local vineyards. The authorized grape varieties for the production of Sherry vinegar are the same that those employed for Sherry wine. The Sherry vinegar production process basically consists in the acetic fermentation of local wines, as a result of the transformation of alcohol in acetic acid by acetic bacteria (Mycoderma aceti) and its subsequent aging in wooden casks. The final product presents a color between old gold and mahogany, with an intense aroma, lightly alcoholic, with notes of wine and wood predominating, and a pleasant taste, despite the acidity, with a long aftertaste [8][9].

On the other hand, Sherry Brandy is the product resulting from the distillation of wines (mainly Airén and Palomino ones) and its subsequent aging to confer the final product its distinctive organoleptic qualities [10].

All these products share in common a singular and dynamic aging process that is characteristic of the Sherry area: ‘Criaderas y Solera’. This aging process uses oak casks, generally American oak (Quercus alba), that may vary between 250 and 600 L volume depending on the product to be obtained. The porosity of the American oak is ideal to allow the contact of the aging product with the oxygen in the air, thus facilitating its oxidation and favoring the aging process. The evolution of all the product physicochemical parameters is largely due to the impact of wood on the aging process. In fact, wood is a definite determinant of the organoleptic properties achieved by all the Sherry oenological products [5,11]. Moreover, the high level of aromatic content of these Sherry products is also influenced by the high level of aromatic composition of the American oak, compared to other types of oaks, such as French oak (Quercus petraea, Quercus robur).

All these products share in common a singular and dynamic aging process that is characteristic of the Sherry area: ‘Criaderas y Solera’. This aging process uses oak casks, generally American oak (Quercus alba), that may vary between 250 and 600 L volume depending on the product to be obtained. The porosity of the American oak is ideal to allow the contact of the aging product with the oxygen in the air, thus facilitating its oxidation and favoring the aging process. The evolution of all the product physicochemical parameters is largely due to the impact of wood on the aging process. In fact, wood is a definite determinant of the organoleptic properties achieved by all the Sherry oenological products [5][11]. Moreover, the high level of aromatic content of these Sherry products is also influenced by the high level of aromatic composition of the American oak, compared to other types of oaks, such as French oak (Quercus petraea, Quercus robur).

During the aging phase in the winemaking process, the capacity of the wood to release certain compounds is essential and will vary according to the size and age (previous uses) of the cask. Thus, the smaller the cask size, the greater the wood surface in contact with the liquid. In this sense, the use of small barrels is not always convenient, since the effect of the wood on the final product could be greater than desirable [12]. Based on experience, 500–600 L barrels seem to be the most appropriate size for the aging of Sherry products, since they provide the ideal balance between wood surface and content volume.

Another characteristic of these wines is that they are aged in preconditioned casks, i.e., casks that have previously contained sherry wine. They are known as “barricas envinadas” (casks in which Sherry wine has been aged). This significantly contribute to providing these products with different nuances depending on the type of preconditioning undergone by the casks [13].

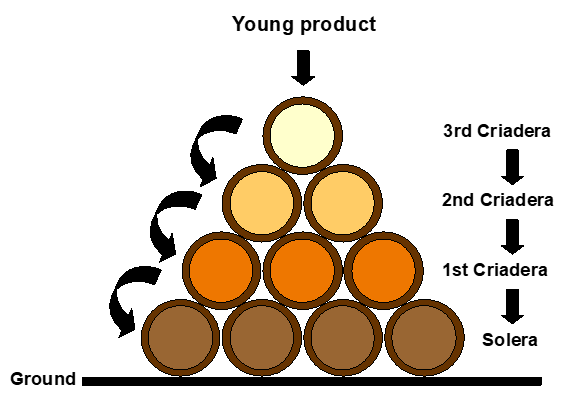

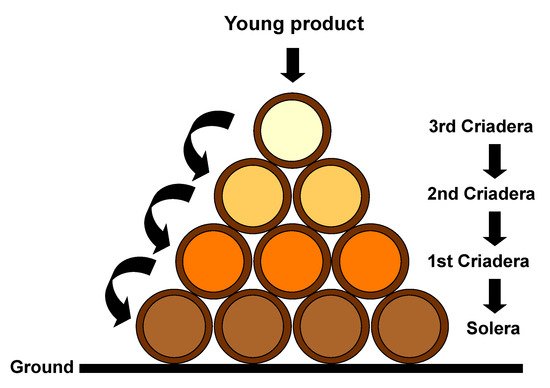

The aforementioned ‘Criaderas y Solera’ aging method could be defined as a dynamic aging process, as opposed to the static aging by vintages. In the latter system, the oenological product to be aged remains in the same barrel during the entire aging period, while in the Criaderas y Solera method, however, the oenological product is stored in casks classified into groups, known as ‘scales’, according to the age of the product that they contain. The scale that contains the oldest oenological product is called ‘solera’ and it is located at ground level. This is topped, according to its younger age, by the first criadera, the second, the third and so on (Figure 1). A small amount of the product, which must be the same from each of the casks that make up the solera, is extracted for bottling and distribution. The resulting empty space is replenished with the equivalent volume of the oenological product from the first criadera. The same procedure is applied to the first and second criadera, which are refilled with the product from the corresponding topping criadera. In this way, a uniform product is obtained in terms of flavor, aroma and color. The same organoleptic characteristics are obtained, since the amount of refilling product is rather reduced in comparison with the larger amount of product in the receiving cask. Thus, the small amount of product added to the cask acquires the characteristics of the predominant older product it is mixed with [14,15].

The aforementioned ‘Criaderas y Solera’ aging method could be defined as a dynamic aging process, as opposed to the static aging by vintages. In the latter system, the oenological product to be aged remains in the same barrel during the entire aging period, while in the Criaderas y Solera method, however, the oenological product is stored in casks classified into groups, known as ‘scales’, according to the age of the product that they contain. The scale that contains the oldest oenological product is called ‘solera’ and it is located at ground level. This is topped, according to its younger age, by the first criadera, the second, the third and so on (Figure 1). A small amount of the product, which must be the same from each of the casks that make up the solera, is extracted for bottling and distribution. The resulting empty space is replenished with the equivalent volume of the oenological product from the first criadera. The same procedure is applied to the first and second criadera, which are refilled with the product from the corresponding topping criadera. In this way, a uniform product is obtained in terms of flavor, aroma and color. The same organoleptic characteristics are obtained, since the amount of refilling product is rather reduced in comparison with the larger amount of product in the receiving cask. Thus, the small amount of product added to the cask acquires the characteristics of the predominant older product it is mixed with [14][15].

Figure 1. Criaderas y Solera aging method.

Criaderas y Solera aging method.

Because of this peculiar aging process, it is quite difficult to estimate the exact age of the oenological product, so it is usually referred to as average age. This parameter is defined as the ratio between the total volume of product in the system and the annual volume that is taken out for its commercialization. Depending on their average age, they will be classified into different categories, which will exhibit different characteristics, depending on the original oenological matrix that was used (wine, vinegar, or Brandy).

All the aforementioned features in the elaboration of Sherry products provide them with their own qualities that will constitute their seal of quality. Thus, such characteristics like polyphenolic compounds content [10,16–18], chromatic attributes [17,19,20], organic acids [13,17], or sugars contents [14] have been suggested to be determinant parameters regarding the ultimate quality of Sherry wine, vinegar, or brandy.

All the aforementioned features in the elaboration of Sherry products provide them with their own qualities that will constitute their seal of quality. Thus, such characteristics like polyphenolic compounds content [10][16][17][18], chromatic attributes [17][19][20], organic acids [13][17], or sugars contents [14] have been suggested to be determinant parameters regarding the ultimate quality of Sherry wine, vinegar, or brandy.

The aroma of oenological products, in general, represents an important determinant of their quality, and there are numerous studies that support this point [21–24]. Although not all volatile compounds contribute to aroma perception [25], the study of aromatic profile is still of major importance, since the acceptance of the final product by the consumer depends on them to a great extent [26]. Consequently, in recent years, significant technological advances have been made in terms of extraction methods and the subsequent analysis of these compounds [27,28]. In parallel, sensory analysis has been consolidated as an essential tool to perform a complete investigation that covers all the aspects related to aroma. An increasing number of studies propose sensory analysis as a crucial tool to determine the quality of the final product [29]. Moreover, a recent study by Cruces-Montes et al. [30] presented the perception of the attributes of Sherry wine and its consumption in young people in the south of Spain. Their results showed that the consumption of Sherry wine was recognized to different dimensions, and flavor was especially important for some types of Sherry wine.

The aroma of oenological products, in general, represents an important determinant of their quality, and there are numerous studies that support this point [21][22][23][24]. Although not all volatile compounds contribute to aroma perception [25], the study of aromatic profile is still of major importance, since the acceptance of the final product by the consumer depends on them to a great extent [26]. Consequently, in recent years, significant technological advances have been made in terms of extraction methods and the subsequent analysis of these compounds [27][28]. In parallel, sensory analysis has been consolidated as an essential tool to perform a complete investigation that covers all the aspects related to aroma. An increasing number of studies propose sensory analysis as a crucial tool to determine the quality of the final product [29]. Moreover, a recent study by Cruces-Montes et al. [30] presented the perception of the attributes of Sherry wine and its consumption in young people in the south of Spain. Their results showed that the consumption of Sherry wine was recognized to different dimensions, and flavor was especially important for some types of Sherry wine.

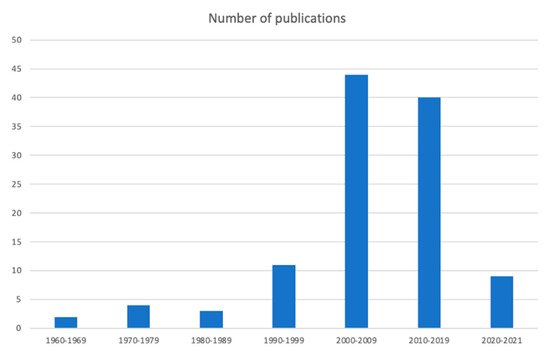

Figure 2 shows the growing progression in the number of studies that address the subject of aroma in the typical products from Jerez (Sherry) area: wine, vinegar, and brandy. This rising number of studies and publications is explained by the importance of the content of volatile compounds regarding the aroma of wine products, as well as by the socioeconomic relevance of these products in the region. Also, the evolution of analytical technologies and their innovations contribute for the increment of this kind of studies. On these bases, we have considered the importance of a literature review that would cover the most prominent aspects associated to this tandem: aroma and Sherry oenological products

You c

2. Study of the Aroma of Dry Sherry Wines

The aromatic content of Sherry wines and, in particular, that of Fino wines, has been extensively studied by employing the analytical methods previously described. Table 1 shows the main aromatic compounds detected in Fino, Amontillado, and Oloroso Sherry wines, together with the bibliographic references where these compounds are mentioned. Sensory descriptors and concentration ranges also appear in Table 1.

Tan access to the compblete review in the following link:

https://www 1.mdpi.com/2304-8158/10/4/753/htm

Volatile compounds identified in dry Sherry wines, sensory descriptors, concentration ranges, and bibliographic references

| Volatile Compounds | Sensory Descriptors | Concentration (mg/L) | References Fino |

References Amontillado | References Oloroso |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonyls | |||||

| Acetaldehyde | Overripe apple | 85–545 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32][38] |

| Acetoin | Butter | 0.011–74 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32] |

| Benzaldehyde | Bitter almond/cherry | 0.013–0.076 | [33][36] | [39] | |

| 2,3-Butanedione | Butter-cookie | 0.170–2.1 | [33][34][36] | [37] | [38] |

| Furfural | Sweet/woody/almond/baked/bread | 0.179–7.14 | [32] | [32] | [32] |

| β-Ionone | Balsamic/rose/violet/berry/phenolic | 0.062 | [32][35] | [32] | |

| Neral | Sweet/citrus/lemon peel | [33] | |||

| Octanal | Herbaceous | 0.090–0.390 | [32][33][34][35][36] | [37] | |

| Acids | |||||

| Butanoic acid | Cheese/butter | 0.607–14.6 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32][38] |

| Decanoic acid | Rancid | 0.004–0.370 | [31][33][36] | [39] | |

| Dodecanoic acid | Mild fatty/coconut/bay oil | [33][36] | |||

| Hexanoic acid | Fatty/sweat/cheese | 0.635–2.39 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32] | [32] |

| Isobutanoic acid | Acidic/cheese/dairy/buttery/rancid | 2.2–22.1 | [31][33][36] | ||

| Isobutyric acid | Acidic/cheese/dairy/buttery/rancid | 0.002–4.58 | [32] | [32][39] | |

| 3-Methylbutanoic acid | Cheese | 1.5–679 | [31][32][33][35][36] | [32][37] | [38] |

| Nonanoic acid | Waxy/cheesy/dairy | 0.003–0.011 | [39] | ||

| Octanoic acid | Fatty/waxy/rancid/oily/cheesy | 0.001–1.6 | [31][33][34][36] | [39] | |

| Alcohols | |||||

| Benzyl alcohol | Floral/rose/phenolic/balsamic | 0.045–3.3 | [31][32][33][36] | [32] | [32] |

| 1-Butanol | Fusel oil/sweet/balsam/whiskey | 0.001–19.9 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32] | [32][39] |

| 2-Butanol | Sweet/apricot | 1.1–4.4 | [31][32][33][35][36] | [32] | [32] |

| 2,3-Butanediol | Fruity/creamy/buttery | [33][36] | |||

| 1-Decanol | Fatty/waxy/floral | 0.124–1.26 | [32][33][35][36] | [32] | [32] |

| 3-Ethoxy-1-propanol | 0.250–0.490 | [31][33][35] | |||

| 1-Heptanol | Musty/pungent/leafy green/apple/banana | 0.300–0.870 | [33] | [32] | [32] |

| Hexanol | Fusel oil/fruity/alcoholic/sweet/green | 0.001–2.5 | [31][32][33][35][36] | [32] | [32][39] |

| E-3-Hexenol | Green/cortex/floral/oily/earthy | 0.055–0.085 | [31][32][35] | ||

| Z-3-Hexenol | Green/grassy/melon rind | 0.055–0.085 | [31][32][33][35] | ||

| Isoamyl alcohols | Vinous/solvent | 0.020–444 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32][38] |

| Isobutanol | Vinous/solvent | 25.7–102 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32] |

| Isopropyl alcohol | Alcohol/musty/woody | 1.4–2.7 | [31] | ||

| Methanol | Slight alcoholic | [33][36] | |||

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol | Roasted/fruity/fusel oil/alcoholic/wine/whiskey | [39] | |||

| 2-Methyl-1-pentanol | 0.020–0.090 | [32] | [32] | [32] | |

| 3-Methyl-1-pentanol | Pungent/fusel oil/brandy/wine/cocoa | 0.110–18 | [31][32][33][35][36] | [32] | [32] |

| 4-Methyl-1-pentanol | Nutty | 0.029–0.135 | [31][32][33][36] | [32] | |

| 1-Octanol | Waxy/green/citrus/aldehydic/floral/coconut | [33][36] | |||

| 1-Pentanol | Pungent/fermented/bready/yeasty/fusel oil/winey/solvent | 0.060–102 | [32][33] | [32] | [32] |

| Phenethyl alcohol | Rose | 0.003–99 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32][38][39] |

| Propanol | Alcoholic/fermented/musty/yeasty/apple/pear | 12.3–16.3 | [31][33][35][36] | ||

| Volatile phenols | |||||

| 4-Ethylguaiacol | Toasted/clove | 0.002–0.740 | [32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32][39] |

| 4-Ethylphenol | Smoke/phenolic/creosote | 0.004–0.094 | [33][36] | [32][39] | |

| Eugenol | Cinnamon/clove | 0.002–0.477 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32][39] |

| Guaiacol | Phenolic/smoke/spice/vanilla/woody | 0.280–0.434 | [39] | ||

| Methyleugenol | Spicy/cinnamon/clove/musty/waxy/phenolic | 0.157 | [32] | ||

| Esters | |||||

| Butyl acetate | Fruity/solvent/banana | 0.091–0.161 | [33] | [32][39] | |

| Diethyl malate | Brown sugar/sweet/wine/fruity/herbal | 0.800–23.6 | [31][32][33][35][36] | [32] | [32] |

| Diethyl succinate | Mild fruity/cooked apple/ylang | 0.001–55.4 | [31][32][33][35][36] | [32] | [32][39] |

| Ethyl acetate | Pineapple/varnish | 13.9–260 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32] |

| Ethyl benzoate | Fruity/dry/musty/sweet/wintergreen | 0.180–0.215 | [32] | [32] | |

| Ethyl butanoate | Banana/apple | 0.172–3.5 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [37] | [32][38][39] |

| Ethyl decanoate | Sweet/waxy/fruity/apple/grape/oily/brandy | 0.22 | [32] | ||

| Ethyl furoate | Balsamic | [33][36] | |||

| Ethyl heptanoate | Fruity/pineapple/brandy/rum/wine | 0.021–0.109 | [32][35] | [32] | [32] |

| Ethyl hexanoate | Almond/apple | 0.078–0.280 | [31][33][34][35][36] | [37] | [38][39] |

| Ethyl 3-hydroxybutanoate | Fruity/green grape/tropical | 0.030–0.747 | [31][33][35][36] | ||

| Ethyl 3-hydroxyhexanoate | Rubber | [33] | [37] | ||

| Ethyl isobutanoate | Apple/pineapple | 0.028–1.660 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32][38] |

| Ethyl isovalerate | Fruity/sweet/apple/pineapple/tutti frutti | 0.001–0.009 | [39] | ||

| Ethyl lactate | Raspberry/milky | 12–854 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32][38] |

| Ethyl laurate | Sweet/waxy/floral/soapy/clean | 0.024–0.140 | [32][35] | [32] | [32] |

| Ethyl myristate | Mild waxy/soapy | 0.099–0.119 | [32][33][35][36] | [32] | |

| Ethyl octanoate | Pear | 0.008–1.3 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [39] |

| Ethyl propanoate | Sweet/fruity/rum/juicy fruit/grape/pineapple | 0.109–1.92 | [31][32][33][35][36] | [32] | [32] |

| Ethyl palmitate | Mild waxy | 0.042–0.070 | [32][35] | [32] | |

| Ethyl pyruvate | Fruity/sweet/rum | 0.081–0.201 | [31][32][33][35][36] | [32] | [32] |

| Ethyl valerate | Sweet/fruity/apple/pineapple/green/tropical | 0.001–0.010 | [39] | ||

| Hexyl acetate | Green/fruity/sweet/fatty/fresh/apple/pear | 0.001–0.008 | [39] | ||

| Hexyl hexanoate | Green/sweet/waxy/fruity/berry | 0.247 | [32] | ||

| Hexyl lactate | Sweet/floral/green/fruity | 1.1 | [32] | ||

| Isoamyl acetate | Banana | 0.050–0.855 | [31][33][34][36] | [37] | [38][39] |

| Isoamyl laurate | Winey/alcoholic/fatty/creamy/yeasty/fusel oil | 0.357 | [32] | ||

| Isobutyl acetate | Sweet/fruity/banana | 0.025–0.137 | [31][33] | [32][39] | |

| Isobutyl isobutanoate | Fruity tropical/fruit pineapple/grape skin/banana | 0.066 | [32] | ||

| Isobutyl lactate | Faint buttery/fruity/caramel | 0.034–0.242 | [32][33][35][36] | [32] | |

| Methyl acetate | Solvent/fruity/winey/brandy/rum | 6.6 | [32] | ||

| Methyl butanoate | Strawberry/butter | 0.486–4.86 | [33][34][36] | [37] | [32][38] |

| Monoethyl succinate | Odorless | [33][36] | |||

| Phenethyl acetate | Flowers | 0.100–1.1 | [31][33][36] | [37] | [38] |

| Phenethyl octanoate | Sweet/waxy/slightly cocoa/caramel/winey/brandy | 0.190–0.275 | [32][33][36] | [32] | |

| Propyl acetate | Solvent/fusel oil/sweet/fruity | 0.042–0.162 | [31][32][33][36] | [32] | [32] |

| Propyl butanoate | Pungent/rancid | 0.112–0.150 | [32][35] | [32] | |

| Terpenes | |||||

| β-Citronellol | Rose | 0.280–1.33 | [31][32][33][35][36] | [32] | |

| Farnesol | Sweet/floral | 0.282–5.79 | [32][35] | [32] | [32] |

| Linalool | Citrus/orange/floral/terpy/waxy/rose | 0.009–0.032 | [31] | [38] | |

| Nerol | Floral/green | 0.151–0.176 | [32][35] | [32] | |

| E-Nerolidol | Floral/green/citrus/woody/waxy | 0.076–0.213 | [32][35] | [32] | [32] |

| Z-Nerolidol | Waxy/floral | 0.696 | [32][33][36] | ||

| 4-Terpineol | Pine | 0.777 | [32] | ||

| α-Terpineol | Pine/woody/resinous/lemon/citrus | 0.006–0.015 | [32][33][35] | [39] | |

| Lactones | |||||

| γ-Butyrolactone | Creamy/oily | 0.004–40.8 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32] | [32][39] |

| γ-Decalactone | Peach | 0.043 | [32][33][34][35][36] | ||

| Pantolactone | 0.470–5.22 | [31][32][33][35][36] | [32] | [32] | |

| Sotolon | Walnut/cotton candy/curry | 0.100–0.670 | [33][34][36] | [37] | [38] |

| cis-Whiskeylactone | Burnt/wood/vanilla/coconut | 0.009–0.410 | [31][34][36] | [37] | [38][39] |

| trans-Whiskeylactone | Sweet/spicy/coconut/vanilla | [33] | [39] | ||

| Miscellaneous | |||||

| Methionol | Cooked potato/cut hay | 0.063–3.4 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32][38] |

| p-Cymene | Citrus/terpene/woody/spice | [33][36] | |||

| 1,1-Diethoxyethane | Green fruit/liquorice | 8.4–58.8 | [31][32][33][34][35][36] | [32][37] | [32][38] |

All types of dry Sherry wines are produced from the same grape, ‘Palomino fino’, and it is the subsequent elaboration of the product (biological or oxidative aging), the main responsible of obtaining wines with different organoleptic characteristics. Also, the extracted wood components induce these changes. Therefore, it is mainly the aging process that will determine the differences between the three types of dry wines: Fino, Oloroso, and Amontillado. Thus, the aroma of Fino wines will be conditioned by the flor velum yeast, which, in addition to shielding the wine from oxygen, will contribute with a series of compounds derived from its metabolism. At the other end, we have the Oloroso wine that undergoes oxidative aging and contains higher levels of alcohol, so that during this aging stage the compounds that were initially present in the wine aroma will evolve due to oxidation, esterification, and other reactions. Finally, Amontillado wines undergo a first stage of biological aging and then an oxidative one [5].

A large number of volatile compounds are common to all of them, including acetaldehyde, acetoin, eugenol, and 1,1-diethoxyethane, among others. Acetaldehyde may come from different sources, although it appears particularly as a secondary product resulting from the aerobic metabolism of the flor velum yeasts responsible for the biological aging process [40][41]. This compound is also the precursor of a large number of other compounds that are involved in the aroma of Sherry wines, either as a result of biological or oxidative aging. In particular, it is the precursor of 1,1-diethoxyethane, one of the main acetals in Sherry wines, which is formed through chemical and biochemical reaction with ethanol [42]. This compound contributes to the fruity aromas and balsamic notes of these wines.

Acetoin is one of the other acetaldehyde-derived compounds with aromatic significance in Sherry wines. This compound is preferentially formed by a condensation reaction of two acetaldehyde molecules [42]. Acetoin is one of the compounds responsible for the bitter notes of Fino wines. The reduction of the acetoin gives rise to 2,3-butanediol, another aromatic compound involved in the aroma of Sherry wines.

The reaction between acetaldehyde and α-ketobutyric acid during the anaerobic metabolism of the yeasts in the flor velum gives rise to sotolon. This compound has a high impact on the aroma of these wines, particularly in the nutty, curry, and cotton candy notes that are present in all the Sherry wines [42].

It should be noted that Sherry wines from exclusively biological aging—i.e., Fino wines—have a particularly high acetaldehyde content, which is actually attributable to their biological aging. This compound is not only responsible for the sharp character of Fino wines’ aroma, but also contributes enriches it with the notes of overripe or ripe apples [33][35][43] that are inherent to this wine.

According to the bibliography, other major volatile compounds to be found in the wine are isoamyl alcohols, ethyl lactate, and 1,1-diethoxyethane (Table 1). A certain number of volatile compounds clearly differentiate Fino wines from other types of Sherry wines, among them E-3-hexenol, Z-3-hexenol, γ-decalactone, terpinen-4-ol, Z-nerolidol, farnesol, and octanal. This suggests that their origin may be linked to the biological aging process that characterizes this wine, and that they do not remain as part of the composition of other wine types, like Amontillado, which undergoes a subsequent oxidative aging procedure.

Other aromatic compounds that play a significant role in the aroma of biologically aged wines are β-citronellol and β-ionone. These compounds are responsible for the citrus and balsamic notes in the aroma of these wines, although they are present at concentration levels of μg/L (Table 1). Other compounds that also stand out are phenethyl octanoate, ethyl palmitate, nerol, propyl butanoate, and ethyl myristate. All of these compounds have been detected in both Fino and Amontillado wines (Table 1).

Amontillado wines, which are obtained through an initial biological aging stage and a subsequent oxidative process as above mentioned, exhibit certain characteristics of their own. For example, they do not contain ethyl benzoate in their composition; they are the only types of Sherry wines that present detectable concentrations of isobutyl isobutanoate (0.066 mg/L) and isoamyl laurate (0.357 mg/L), and present lower concentration levels of 1,1-diethoxyethane, isobutanol, and phenethyl alcohol, while their levels of E-nerolidol are higher with respect to that in Fino or Oloroso wines [32]. The main volatile compounds that can be found in Amontillado wines are ethyl lactate, acetaldehyde, isoamyl alcohols, diethyl succinate, and ethyl acetate, all of them at levels of concentration of dozens or even hundreds of mg/L (Table 1). It has long been known that oxidative aging results in a higher concentration of esterified compounds in Amontillado wines, since their greater concentration of ethanol results in evident increment in ethyl lactate and ethyl acetate concentrations during the aging phase [32]. However, the compound that contributes the most to the aroma of Amontillado wines is ethyl octanoate, that is usually present at concentrations below 1 mg/L [37], followed by ethyl butanoate, eugenol, ethyl isobutanoate, and sotolon, which maintain their relative contributions to the wine aroma throughout the period of oxidative aging, even though their concentrations increase with time. It is precisely this second aging stage, the oxidative one, which confers Amontillado wines their main odorant characteristics.

Considerable levels of acetaldehyde are also found in Oloroso and Amontillado wines, although in lower concentrations than in Fino wines (around five times lower) [42]. The most abundant compounds in Oloroso wines are isoamyl alcohols, ethyl lactate, ethyl acetate, acetaldehyde, and diethyl succinate. Other compounds such as ethyl butyrate, ethyl caproate, ethyl decanoate, ethyl isovalerate, ethyl valerate, guaiacol, hexyl acetate, hexyl hexanoate, hexyl lactate, methyl acetate, 2-methylbutan-1-ol, methyleugenol, β-methyl-γ-octalactone, nonanoic acid, 2-phenylethanol, and 2-phenylethanol acetate tend to be more characteristic of Oloroso wines, and are not found either in Amontillado or Fino wines.

The narrow correlation between the aromatic composition of Sherry wines and the type of cask wood as well as the degree of toasting of the wood has already been studied [39]. The wines aged in French oak and chestnut casks undergo greater changes in their volatile compound composition during the oxidative aging process. American and Spanish oak, on the other hand, modify to a lesser degree the volatile compound profile of these wines during their aging. In relation to the wood toasting degree, it is the medium-toasted casks that produces the wines with the greatest volatile composition. These results are similar to those reported by other authors with regard to fortified and sweet wines aged in wood [44][45]. Eugenol and guaiacol are compounds derived from the degradation of lignin and their content increases during the aging in contact with wood. β-methyl-γ-octalactone was only identified in Oloroso wines aged in contact with oak wood, but not in those aged with chestnut. High concentrations of γ-butyrolactone were also determined in all the samples studied, similarly to those already reported by Hevia et al. [44]. Ethyl valerate, hexyl acetate, or ethyl octanoate (compounds that contribute with floral and fruity notes to the aroma of the wines) decreased with aging, except for the wines aged in French oak casks, which saw their concentration increased along with other compounds such as isobutyl acetate, ethyl valerate or isoamyl acetate.

References

- Pardo-Calle, C.; Segovia-Gonzalez, M.M.; Paneque-Macias, P.; Espino-Gonzalo, C. An approach to zoning in the wine growing regions of “Jerez-Xérès-Sherry” and “Manzanilla-Sanlúcar de Barrameda” (Cádiz, Spain). INIA Span. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 9, 831–843.

- Johnson, H.; Robinson, J. The World Atlas of Wine, 8th ed.; Mitchell Beazley: London, UK, 2019.

- Pozo-Bayón, M.A.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Sherry Wines: Manufacture, Composition and Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 779–784.

- Marin-Menguiano, M.; Romero-Sanchez, S.; Barrales, R.R.; Ibeas, J.I. Population analysis of biofilm yeasts during fino sherry wine aging in the Montilla-Moriles, D.O. region. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 244, 67–73, doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.12.019.

- Pozo-Bayón, M.A.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Sherry Wines. In Advances in Food and Nutrition Research; Academic Press Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 63, pp. 17–40.

- Consejería de Agricultura y Pesca. Orden de 13 de Mayo de 2010, por la que se Aprueba el Reglamento de las Denominaciones de Origen «Jerez-Xérès-Sherry» y «Manzanilla de Sanlúcar de Barrameda», así Como sus Correspondientes Pliegos de Condiciones; Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía (BOJA): Sevilla, Spain, 2010; Volume 103, pp. 53–74.

- Council of the European Union. Council Regulation (EEC) No 4252/88 of 21 December 1988 on the Preparation and Marketing of Liqueur Wines Produced in the Community; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 1988.

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Orden de 26 de Diciembre de 2000 por la que se Ratifica el Reglamento de la Denominación de Origen «Vinagre de Jerez»; Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE): Madrid, Spain, 2000; p. 24477.

- Council of the European Union. Council Regulation (EC) No 510/2006 of 20 March 2006 on the Protection of Geographical Indications and Designations of Origin for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Dodero, M.C.R.; Sánchez, D.A.G.; Rodríguez, M.S.; Barroso, C.G. Phenolic compounds and furanic derivatives in the characterization and quality control of Brandy de Jerez. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 990–997, doi:10.1021/jf902965p.

- Carpena, M.; Pereira, A.G.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Wine aging technology: Fundamental role of wood barrels. Foods 2020, 9, doi:10.3390/foods9091160.

- Pérez-Prieto, L.J.; López-Roca, J.M.; Martínez-Cutillas, A.; Pardo Mínguez, F.; Gómez-Plaza, E. Maturing wines in oak barrels. Effects of origin, volume, and age of the barrel on the wine volatile composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3272–3276, doi:10.1021/jf011505r.

- Sánchez-Guillén, M.M.; Schwarz-Rodríguez, M.; Rodríguez-Dodero, M.C.; García-Moreno, M.V.; Guillén-Sánchez, D.A.; García-Barroso, C. Discriminant ability of phenolic compounds and short chain organic acids profiles in the determination of quality parameters of Brandy de Jerez. Food Chem. 2019, 286, 275–281, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.02.006.

- Martínez Montero, C.; Rodríguez Dodero, M.D.C.; Guillén Sánchez, D.A.; García Barroso, C. Sugar contents of Brandy de Jerez during its aging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1058–1064, doi:10.1021/jf0403078.

- Ruiz-Muñoz, M.; Cordero-Bueso, G.; Benítez-Trujillo, F.; Martínez, S.; Pérez, F.; Cantoral, J.M. Rethinking about flor yeast diversity and its dynamic in the “criaderas and soleras” biological aging system. Food Microbiol. 2020, 92, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2020.103553.

- Palacios, V.; Valcárcel, M.; Caro, I.; Pérez, L. Chemical and biochemical transformations during the industrial process of sherry vinegar aging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4221–4225, doi:10.1021/jf020093z.

- Schwarz, M.; Rodríguez, M.C.; Guillén, D.A.; Barroso, C.G. Analytical characterisation of a Brandy de Jerez during its ageing. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2011, 232, 813–819, doi:10.1007/s00217-011-1448-2.

- Cejudo Bastante, M.J.; Durán Guerrero, E.; Castro Mejías, R.; Natera Marín, R.; Rodríguez Dodero, M.C.; Barroso, C.G. Study of the polyphenolic composition and antioxidant activity of new sherry vinegar-derived products by maceration with fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11814–11820, doi:10.1021/jf1029493.

- Delgado-González, M.J.; García-Moreno, M.V.; Sánchez-Guillén, M.M.; García-Barroso, C.; Guillén-Sánchez, D.A. Colour evolution kinetics study of spirits in their ageing process in wood casks. Food Control 2021, 119, doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107468.

- Recamales, A.F.; Hernanz, D.; Álvarez, C.; González-Miret, M.L.; Heredia, F.J. Colour of Amontillado wines aged in two oak barrel types. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2007, 224, 321–327, doi:10.1007/s00217-006-0399-5.

- Ding, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, S.; Liang, J.; Xi, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Yu, H.; Guo, S. Characterization of biochemical compositions, volatile compounds and sensory profiles of cabernet sauvignon wine in successive vintages (2008–2017). Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 16, 380–391, doi:10.3844/ajbbsp.2020.380.391.

- Pati, S.; Crupi, P.; Savastano, M.L.; Benucci, I.; Esti, M. Evolution of phenolic and volatile compounds during bottle storage of a white wine without added sulfite. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 775–784, doi:10.1002/jsfa.10084.

- Niimi, J.; Tomic, O.; Næs, T.; Bastian, S.E.P.; Jeffery, D.W.; Nicholson, E.L.; Maffei, S.M.; Boss, P.K. Objective measures of grape quality: From Cabernet Sauvignon grape composition to wine sensory characteristics. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 123, doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109105.

- Zea, L.; Ruiz, M.J.; Moyano, L.Using Odorant Series as an Analytical Tool for the Study of the Biological Ageing of Sherry Wines. In Gas Chromatography in Plant Science, Wine Technology, Toxicology and Some Specific Applications; InTechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012.

- Dunkel, A.; Steinhaus, M.; Kotthoff, M.; Nowak, B.; Krautwurst, D.; Schieberle, P.; Hofmann, T. Nature’s chemical signatures in human olfaction: A foodborne perspective for future biotechnology. Angewandte Chemie 2014, 53, 7124–7143, doi:10.1002/anie.201309508.

- Souza Gonzaga, L.; Capone, D.L.; Bastian, S.E.P.; Jeffery, D.W. Defining wine typicity: Sensory characterisation and consumer perspectives. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2020, 27, 246–256, doi:10.1111/ajgw.12474.

- Welke, J.E.; Hernandes, K.C.; Nicolli, K.P.; Barbará, J.A.; Biasoto, A.C.T.; Zini, C.A. Role of gas chromatography and olfactometry to understand the wine aroma: Achievements denoted by multidimensional analysis. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 44, 135–168, doi:10.1002/jssc.202000813.

- Marín-San Román, S.; Rubio-Bretón, P.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P.; Garde-Cerdán, T. Advancement in analytical techniques for the extraction of grape and wine volatile compounds. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109712.

- Pérez-Elortondo, F.J.; Symoneaux, R.; Etaio, I.; Coulon-Leroy, C.; Maître, I.; Zannoni, M. Current status and perspectives of the official sensory control methods in protected designation of origin food products and wines. Food Control 2018, 88, 159–168, doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.01.010.

- Cruces-Montes, S.J.; Merchán-Clavellino, A.; Romero-Moreno, A.; Paramio, A. Perception of the attributes of sherry wine and its consumption in young people in the South of Spain. Foods 2020, 9, 417, doi:10.3390/foods9040417.

- Cortes, M.B.; Moreno, J.J.; Zea, L.; Moyano, L.; Medina, M. Response of the aroma fraction in Sherry wines subjected to accelerated biological aging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3297–3302, doi:10.1021/jf9900130.

- Zea, L.; Moyano, L.; Moreno, J.; Cortes, B.; Medina, M. Discrimination of the aroma fraction of Sherry wines obtained by oxidative and biological ageing. Food Chem. 2001, 75, 79–84, doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00190-X.

- Zea, L.; Moyano, L.; Moreno, J.A.; Medina, M. Aroma series as fingerprints for biological ageing in fino sherry-type wines. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2007, 87, 2319–2326, doi:10.1002/jsfa.2992.

- Zea, L.; Moyano, L.; Ruiz, M.J.; Medina, M. Chromatography-Olfactometry Study of the Aroma of Fino Sherry Wines. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2010, 2010, 1–5, doi:10.1155/2010/626298.

- Moyano, L.; Zea, L.; Moreno, J.; Medina, M. Analytical study of aromatic series in sherry wines subjected to biological aging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 7356–7361, doi:10.1021/jf020645d.

- Moreno, J.A.; Zea, L.; Moyano, L.; Medina, M. Aroma compounds as markers of the changes in sherry wines subjected to biological ageing. Food Control 2005, 16, 333–338, doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2004.03.013.

- Moyano, L.; Zea, L.; Moreno, J.A.; Medina, M. Evaluation of the active odorants in Amontillado sherry wines during the aging process. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6900–6904, doi:10.1021/jf100410n.

- Zea, L.; Moyano, L.; Ruiz, M.J.; Medina, M. Odor descriptors and aromatic series during the oxidative aging of oloroso sherry wines. Int. J. Food Prop. 2013, 16, 1534–1542, doi:10.1080/10942912.2011.599093.

- García-Moreno, M.V.; Sánchez-Guillén, M.M.; Delgado-González, M.J.; Durán-Guerrero, E.; Rodríguez-Dodero, M.C.; Guillén-Sánchez, D.A.; García-Barroso, C. Chemical content and sensory changes of Oloroso Sherry wine when aged with four different wood types. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 140, 110706, doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110706.

- Garcia-Maiquez, E. Les levures de voile dans l’élaboration des vins de Xéres. In Proceedings of the Application a l’Oenologie des Progres Recents en Microbiologie et en Fermentation; OIV (Ed.): Paris, France, 1988; pp. 341–351.

- Martínez, P.; Pérez Rodríguez, L.; Benítez, T. Velum formation by flor yeast isolated from Sherry wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1997, 48, 55–62.

- Zea, L.; Serratosa, M.P.; Mérida, J.; Moyano, L. Acetaldehyde as Key Compound for the Authenticity of Sherry Wines: A Study Covering 5 Decades. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015, 14, 681–693, doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12159.

- Muñoz, D.; Peinado, R.A.; Medina, M.; Moreno, J. Biological aging of sherry wines under periodic and controlled microaerations with Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. capensis: Effect on odorant series. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 1188–1195, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.10.065.

- Hevia, K.; Castro, R.; Natera, R.; González-García, J.A.; Barroso, C.G.; Durán-Guerrero, E. Optimization of Head Space Sorptive Extraction to Determine Volatile Compounds from Oak Wood in Fortified Wines. Chromatographia 2016, 79, 763–771, doi:10.1007/s10337-016-3088-y.

- Herrera, P.; Durán-Guerrero, E.; Sánchez-Guillén, M.M.; García-Moreno, M.V.; Guillén, D.A.; Barroso, C.G.; Castro, R. Effect of the type of wood used for ageing on the volatile composition of Pedro Ximénez sweet wine. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 2512–2521, doi:10.1002/jsfa.10276.