The circularization of viral genomes fulfills various functions, from evading host defense mechanisms to promoting specific replication and translation patterns supporting viral proliferation. Here, wthis entry describes the genomic structures and associated host factors important for flaviviruses genome circularization and summarize their functional roles. Flaviviruses are relatively small, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA viruses with genomes of approximately 11 kb in length. These genomes contain motifs at their 5′ and 3′ ends, as well as in other regions, that are involved in circularization. These motifs are highly conserved throughout the Flavivirus genus and occur both in mature virions and within infected cells.

- flavivirus

- circular RNA

- dengue

- Zika

- viruses

1. Introduction

Flaviviruses comprise a number of arthropod-borne infections, most of which are prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions around the globe [1][2][3][4]. Prominent members of the

genus include yellow fever (YFV), tick-borne encephalitis (TBEV), Japanese encephalitis (JEV), Zika (ZIKV), West Nile (WNV), and dengue (DENV) viruses [5][6]. DENV, transmitted by

spp. female mosquitoes (

and

), is estimated to infect approximately 400 million people per year, with some cases progressing to hemorrhagic dengue fever, leading to over 20,000 deaths worldwide every year [3]. Whereas vaccines are available and effective against YFV, a broadly effective vaccine against all four subtypes of DENV (DENV-1 to DENV-4), or against ZIKV, remains elusive [7][8]. ZIKV, transmitted by the same mosquitoes, is also a global concern due, among other factors, to the continued expansion of these mosquito vectors. Approaches to deal with DENV and ZIKV infections focus mainly on relieving and managing the symptoms. Appropriate medical care of patients progressing to severe dengue can reduce the mortality rate from approximately 20% to 1% [3]. However, this approach alone is insufficient, as medical care may not be affordable or available to vulnerable socio-economic groups in developing countries where flavivirus infections are most prevalent. Therefore, reducing the number of infections is also imperative. Moreover, as highlighted by the ongoing severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)/COVID-19 pandemic, rapid outbreaks can locally saturate medical care units, even in developed countries, by overwhelming the national healthcare system’s capacity. Further research of preventive or therapeutic strategies is critical, as their immediate availability could mitigate limited medical resources. In addition to accelerated spread, ZIKV poses risks not associated with DENV. Complications such as microcephaly and other neurological conditions arising from ZIKV infection may occur and add to a total mortality rate near 8%, as demonstrated in Brazil [9]. Both DENV and ZIKV cases have been rising in recent years, not only in at-risk developing countries, but also in developed nations, since outbreaks associated with travel are now documented in Europe and North America [3][10][11][12]. Two causal factors, operating concurrently, increase the spread of flavivirus infection: (i) globalization of travel and trade, which escalates virus circulation by exposing naive populations to these infectious agents of foreign origin, plus (ii) the expansion of mosquito habitat due to climate change, urbanization, and other factors that help to establish reservoir vector populations in regions that were previously inhospitable to these arthropods [13][14][15][16][17]. These changes in flaviviruses distribution and vector routes support predictions of further expansion worldwide. Thus, effective and readily available treatments and/or prophylactic measures have become a top priority of governments worldwide, with preventative actions being the best approach to deal with the devastating effects of major epidemics on affected populations and their countries’ economies.

2. General Genome Structure

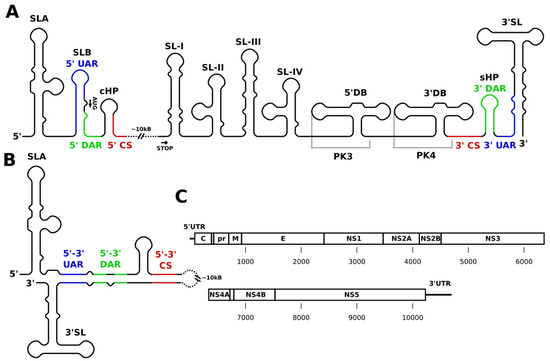

Flaviviruses contain single-stranded (+)-sense RNA genomes approximately 11 kilobases (kb) in length, with a single open reading frame encoding a genomic polyprotein that is post-translationally processed into its constituent parts. These genomes encode three structural proteins at the 5′ end, namely the capsid (C), precursor membrane, and the envelope protein, plus seven nonstructural proteins (detailed ahead). All flavivirus genomes include a short 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of approximately 100 nucleotides (nt) and a variable-length 3′ UTR containing a number of crucial RNA motifs broadly conserved across the family. As shown in

A, these motifs comprise a 5′ stem loop (SLA), a short hairpin (SLB), a capsid hairpin (cHP) at the 5′ end, and at the 3′ end of the genome frequently two dumbbell structures (5′ and 3′ DB) upstream of a terminal 3′ stem loop (3′ SL), and another short hairpin (sHP, also referred to as a “small stem loop” or SSL by some authors), which is preceded in sequence by a variable combination of stem-loops (SL), from 1 to 4 (SL-I to SL-IV), at the 5′ end of the 3′ UTR. In addition to these structures in the 5′ and 3′ regions, recent large-scale structure probing and crosslinking studies of DENV and ZIKV revealed a variety of conserved structural elements throughout the coding region, and functional experiments have demonstrated their importance for viral fitness [18][19][20]. In

, key elements are identified within a simplified graphical linear schematic of flaviviruses genomes. Overall, the flavivirus genome is relatively rich in conserved nucleotide sequences integrated into a variety of functional secondary structure elements with important roles in regulation and viral replication. The following section presents major functional regions individually and describes their particular structural characteristics.

Structural overview of flaviviral genomes. (

) Schematic representation of the linear 5′ and 3′ untranslated region (UTRs). Circularization motifs are indicated and labeled in color. The upstream AUG region (UAR; blue) is followed by the downstream AUG region (DAR; green) and the highly conserved circularization sequence (CS; red). Translation initiation happens within stem loop B (SLB) between 5′ UAR and 5′ DAR. The order of circularization sequence motifs is inverted in the 3′ region. (

) The circular form of the genome (paired motifs shown in color). SLB, capsid hairpin (cHP), short hairpin (sHP), and 3′SL undergo structural reorganization upon circularization. (

) Overview of flaviviral RNA genes. An ≈100 nt 5′ UTR is followed by a ≈10 kb single open reading frame coding a single genome polyprotein, which is post-translationally processed to form the structural (C, prM, and E) and non-structural proteins comprising the flaviviral proteome. The open reading frame is followed by an ≈300–700 nucleotides (depending on species) 3′ UTR containing conserved structural elements.

3. Circularization Structures

The occurrence of 5′-3′ circularization through intramolecular duplexes formation is conserved across the flaviviruses family, and it is effected by three complementary regions: (i) the DAR, (ii) the UAR, and (iii) the circularization sequence (CS) [21][22]. The circularization motif was first identified as a conserved sequence near the 3′ UTR by Hahn et al. [23]. These authors also located a complementary conserved element in the 5′ UTR and postulated potential circularization in a flaviviruses. The functional importance of these sites was shown by Men et al. [24] by examining various deletion mutants in the 3′ UTR [23]. Their study showed that all 3′ UTR deletion mutants of DENV-4 were viable (albeit attenuated), as long as the deletion did not include the last 113 nucleotides containing the circularization motif and 3′ SL. Subsequently, 5′–3′ interactions were shown to be important for other flaviviruses [25][26][27]. The DAR/UAR/CS cyclization motif is thought to act as a single regulatory unit. As Zhang et al. [28] have shown, deletion of CS in WNV is lethal, but can be rescued by compensatory strengthening of interactions in the DAR/UAR regions.

The UAR is located closer to the 5′ and 3′ ends than the CS. The UAR and DAR are mostly contained in structured elements in the linear form of the genomic RNA, whereas the CS is located in a single-stranded stretch between 3′ DB and sHP. Consequently, these structural elements undergo rearrangement upon circularization. Such a feature has been previously observed in different (+)-sense RNA viruses. Olsthoorn et al. described a conformational change in the 3′ region of plant viruses of the Alfamovirus and Ilarvirus families that is necessary to initiate viral replication [29]. In particular, 5′-3′ circularization as a regulatory point controlling RNA replication has been described for Tombusvirus, as negative-strand synthesis is inhibited by formation of the circular form [30]. Circularization as a regulatory mechanism is not confined to the 5′ and 3′ terminal regions, as demonstrated by Zhang et al. [31][32]. They found that an interaction of a 3′ structural element in the turnip crinkle virus genome with a large internal loop structure suppresses negative-strand RNA transcription and posit that such inhibitory motifs are responsible for asymmetric ratios of negative to positive strands in a range from 1:10 to 1:1000 during RNA-dependent RNA polymerase-dependent transcription [31][32].

Circularization of the genome is essential for its replication [25][26][27][33]. Corver et al. [33] identified specific interacting nucleotides of YFV in the 5′ UTR necessary for replication, such as an 18 nt stretch at positions 146–163, with a slightly longer stretch of 21 nucleotides (146–166), required for full replication efficiency, which is a longer segment than the universally conserved 8 nucleotides across flaviviruses. Noteworthy, not all sequences involved in the 3′–5′ interaction are located in the 5′ UTR (as some are in the coding region). Circularization has been shown to be necessary for (-) strand synthesis. Moreover, requirements for replication rely on the presence of specific nucleotides at certain positions beyond the requirement for complementarity [34]. Alvarez et al. [34] demonstrated that specific mutations within the UAR caused a significant delay in viral replication for variants with multiple mutations, despite reconstituted complementarity and the ability to form cyclical genomes in these variants. A possible explanation for this effect is that the sequences are multifunctional and have specific roles in the linear and circular form, forming either a local or a long-range interaction; whereas the transposition of these sequences would maintain their function in the circular state, the function in the local context of the linear form would be disrupted [34].

Lott and Doran [35] suggested that under cellular conditions, the formation of dimeric or multimeric forms connected by their respective circularization sequences is more likely. This argument is based on molecular crowding in local environments that arise from the remodeling of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane induced by flavivirus infection [36]. Brinton et al. [37] dispute that the formation of concatemers on the ground would lead to increased efficiency of minus strand synthesis, which is inconsistent with available evidence on minus strand abundance throughout the replication cycle [37]. WNV variants with a high abundance of minus strand have been shown to have decreased virus production and decreased positive strand levels [38]. Evidence from structure-probing studies show that a cyclized form is present in virions [18][19][20] and is consistently one of the most pronounced signals. Overall, genome circularisation is a key aspect of flaviviruses biology with important implications that must be considered in order to develop full models of the viruses biological activity.

References

- Aedes Albopictus - actsheet for Experts. Available online: (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Aedes Aegypti - Factsheet for Experts. Available online: (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Dengue and Severe Dengue. Available online: (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Zika Virus. Available online: (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Kuhn, R.J.; Rossmann, M.G. A structural perspective of the Flavivirus life cycle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 13–22.

- Ng, W.C.; Soto-Acosta, R.; Bradrick, S.S.; Garcia-Blanco, M.A.; Ooi, E.E. The 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of the flaviviral genome. Viruses 2017, 9, 137.

- Thomas, S.J.; Yoon, I.K. A review of Dengvaxia®: Development to deployment. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 2295–2314.

- Halstead, S. Recent advances in understanding dengue. F1000Research 2019, 8, 1279.

- Da Cunha, A.J.L.A.; De Magalhães-Barbosa, M.C.; Lima-Setta, F.; De Andrade Medronho, R.; Prata-Barbosa, A. Microcephaly case fatality rate associated with Zika virus infection in Brazil. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2016, 36, 528–530.

- Dengue in the US States and Territories | Dengue | CDC. Available online: (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Statistics and Maps | Zika Virus | CDC. Available online: (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Surveillance Atlas of Infectious Diseases. Available online: (accessed on 6 July 2020).

- Iwamura, T.; Guzman-Holst, A.; Murray, K.A. Accelerating invasion potential of disease vector Aedes aegypti under climate change. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2130.

- Kamal, M.; Kenawy, M.A.; Rady, M.H.; Khaled, A.S.; Samy, A.M. Mapping the global potential distributions of two arboviral vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus under changing climate. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0210122.

- Caminade, C.; Medlock, J.M.; Ducheyne, E.; McIntyre, K.M.; Leach, S.; Baylis, M.; Morse, A.P. Suitability of European climate for the Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus: Recent trends and future scenarios. J. R. Soc. Interface 2012, 9, 2708–2717.

- Powell, J.R.; Tabachnick, W.J. History of domestication and spread of Aedes aegypti—A review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2013, 108, 11–17.

- Kraemer, M.U.G.; Reiner, R.C.; Brady, O.J.; Messina, J.P.; Gilbert, M.; Pigott, D.M.; Yi, D.; Johnson, K.; Earl, L.; Marczak, L.B.; et al. Past and future spread of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 854–863.

- Ziv, O.; Gabryelska, M.M.; Lun, A.T.L.; Gebert, L.F.R.; Sheu-Gruttadauria, J.; Meredith, L.W.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Kwok, C.K.; Qin, C.-F.; MacRae, I.J.; et al. COMRADES determines in vivo RNA structures and interactions. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 785–788.

- Huber, R.G.; Lim, X.N.; Ng, W.C.; Sim, A.Y.L.; Poh, H.X.; Shen, Y.; Lim, S.Y.; Sundstrom, K.B.; Sun, X.; Aw, J.G.; et al. Structure mapping of dengue and Zika viruses reveals functional long-range interactions. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1408.

- Li, P.; Wei, Y.; Mei, M.; Tang, L.; Sun, L.; Huang, W.; Zhou, J.; Zou, C.; Zhang, S.; Qin, C.-F.; et al. Integrative Analysis of Zika Virus Genome RNA Structure Reveals Critical Determinants of Viral Infectivity. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 875–886.

- Mazeaud, C.; Freppel, W.; Chatel-Chaix, L. The Multiples Fates of the Flavivirus RNA Genome During Pathogenesis. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 595.

- Sanford, T.J.; Mears, H.V.; Fajardo, T.; Locker, N.; Sweeney, T.R. Circularization of flavivirus genomic RNA inhibits de novo translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 9789–9802.

- Hahn, C.S.; Hahn, Y.S.; Rice, C.M.; Lee, E.; Dalgarno, L.; Strauss, E.G.; Strauss, J.H. Conserved elements in the 3′ untranslated region of flavivirus RNAs and potential cyclization sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1987, 198, 33–41.

- Men, R.; Bray, M.; Clark, D.; Chanock, R.M.; Lai, C.J. Dengue type 4 virus mutants containing deletions in the 3′ noncoding region of the RNA genome: Analysis of growth restriction in cell culture and altered viremia pattern and immunogenicity in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 3930–3937.

- Khromykh, A.A.; Meka, H.; Guyatt, K.J.; Westaway, E.G. Essential Role of Cyclization Sequences in Flavivirus RNA Replication. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 6719–6728.

- Alvarez, D.E.; Lodeiro, M.F.; Ludueña, S.J.; Pietrasanta, L.I.; Gamarnik, A.V. Long-Range RNA-RNA Interactions Circularize the Dengue Virus Genome. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 6631–6643.

- Lo, M.K.; Tilgner, M.; Bernard, K.A.; Shi, P.-Y. Functional Analysis of Mosquito-Borne Flavivirus Conserved Sequence Elements within 3′ Untranslated Region of West Nile Virus by Use of a Reporting Replicon That Differentiates between Viral Translation and RNA Replication. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10004–10014.

- Zhang, B.; Dong, H.; Ye, H.; Tilgner, M.; Shi, P.Y. Genetic analysis of West Nile virus containing a complete 3′CSI RNA deletion. Virology 2010, 408, 138–145.

- Olsthoorn, R.C.L.; Mertens, S.; Brederode, F.T.; Bol, J.F. A conformational switch at the 3′ end of a plant virus RNA regulates viral replication. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 4856–4864.

- Pogany, J.; Fabian, M.R.; White, K.A.; Nagy, P.D. A replication silencer element in a plus-strand RNA virus. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 5602–5611.

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Simon, A.E. Repression and Derepression of Minus-Strand Synthesis in a Plus-Strand RNA Virus Replicon. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 7619–7633.

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; George, A.T.; Baumstark, T.; Simon, A.E. Conformational changes involved in initiation of minus-strand synthesis of a virus-associated RNA. RNA 2006, 12, 147–162.

- Corver, J.; Lenches, E.; Smith, K.; Robison, R.A.; Sando, T.; Strauss, E.G.; Strauss, J.H. Fine Mapping of a cis-Acting Sequence Element in Yellow Fever Virus RNA That Is Required for RNA Replication and Cyclization. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 2265–2270.

- Alvarez, D.E.; Filomatori, C.V.; Gamarnik, A.V. Functional analysis of dengue virus cyclization sequences located at the 5′ and 3′UTRs. Virology 2008.

- Lott, W.B.; Doran, M.R. Do RNA viruses require genome cyclisation for replication? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013, 38, 350–355.

- Welsch, S.; Miller, S.; Romero-Brey, I.; Merz, A.; Bleck, C.K.E.; Walther, P.; Fuller, S.D.; Antony, C.; Krijnse-Locker, J.; Bartenschlager, R. Composition and Three-Dimensional Architecture of the Dengue Virus Replication and Assembly Sites. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 365–375.

- Brinton, M.A.; Basu, M. Functions of the 3′ and 5′ genome RNA regions of members of the genus Flavivirus. Virus Res. 2015.

- Davis, W.G.; Blackwell, J.L.; Shi, P.-Y.; Brinton, M.A. Interaction between the Cellular Protein eEF1A and the 3′-Terminal Stem-Loop of West Nile Virus Genomic RNA Facilitates Viral Minus-Strand RNA Synthesis. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 10172–10187.