The NF-Y gene family is a highly conserved set of transcription factors. The functional transcription factor complex is made up of a trimer between NF-YA, NF-YB, and NF-YC proteins. While mammals typically have one gene for each subunit, plants often have multigene families for each subunit which contributes to a wide variety of combinations and functions. Soybean plants with an overexpression of a particular NF-YC isoform

GmNF-YC4-2

(Glyma.04g196200) in soybean cultivar Williams 82, had a lower amount of starch in its leaves, a higher amount of protein in its seeds, and increased broad disease resistance for bacterial, viral, and fungal infections in the field, similar to the effects of overexpression of its isoform

GmNF-YC4-1

(Glyma.06g169600). Interestingly,

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

(overexpression) plants also filled pods and senesced earlier, a novel trait not found in

GmNF-YC4-1-OE

plants. No yield difference was observed in

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

compared with the wild-type control. Sequence alignment of GmNF-YC4-2, GmNF-YC4-1 and AtNF-YC1 indicated that faster maturation may be a result of minor sequence differences in the terminal ends of the protein compared to the closely related isoforms.

- NF-YC4 transcription factor

- early maturation

- disease resistance

- seed protein

1. Introduction

Effectively feeding an ever-growing global population begins with nutrient rich, resilient crops. Over one in seven people in the world do not have access to a sufficient protein supply in their diets [1]. In addition, the majority of the population relies on a plant-based diet for their protein uptake [2]. As most livestock also requires plant-based diets for their protein, the dietary needs of the world can mostly be attributed to plants. Thus, generating plants with increased protein content can help efficiently feed the global population.

Crop plants such as

Glycine max (soybean) are grown in a wide range of environments and face a multitude of both biotic and abiotic challenges. While plants have evolved a complex immune system [3][4][5][6][7], crops across the world suffer yield loss due to diseases [8][9][10][11] and environmental factors [12][13]. Many genetic engineering methods have been used to combat these factors [8][14]. However, many of these induce constitutively active defense responses that can in turn negatively affect the growth and yield of the plant [15][16]. For example, silencing mitogen-activated protein kinase

(soybean) are grown in a wide range of environments and face a multitude of both biotic and abiotic challenges. While plants have evolved a complex immune system [3,4,5,6,7], crops across the world suffer yield loss due to diseases [8,9,10,11] and environmental factors [12,13]. Many genetic engineering methods have been used to combat these factors [8,14]. However, many of these induce constitutively active defense responses that can in turn negatively affect the growth and yield of the plant [15,16]. For example, silencing mitogen-activated protein kinase

MAPK4

in soybean plants severely stunts the plants when providing a resistance to pathogens [17]. Therefore, genetic engineered resistance that allows for an enhanced pathogen resistance while avoiding major growth defects is important.

While plants have evolved a complex immune system to deal with minor biotic and abiotic perturbations, they have also evolved a more drastic mechanism to deal with seasonal environmental changes. As plants are sessile organisms, rather than maintaining full function throughout a harsh season, they instead undergo programmed cell death called senescence [18][19][20]. This process allows for nutrient re-localization, such as nitrogen remobilization from leaves to seeds, and it is important for seed quality and nitrogen use efficiency [21][22][23][24]. With the looming threat of climate change and the growing global population, the challenge set before us is to improve crop nitrogen use efficiency in order to allow for less reliance on nitrate fertilizers [22]. It has been speculated that stimulating autophagy during stress response could improve crops’ resistance to the effects of climate change [22].

While plants have evolved a complex immune system to deal with minor biotic and abiotic perturbations, they have also evolved a more drastic mechanism to deal with seasonal environmental changes. As plants are sessile organisms, rather than maintaining full function throughout a harsh season, they instead undergo programmed cell death called senescence [18,19,20]. This process allows for nutrient re-localization, such as nitrogen remobilization from leaves to seeds, and it is important for seed quality and nitrogen use efficiency [21,22,23,24]. With the looming threat of climate change and the growing global population, the challenge set before us is to improve crop nitrogen use efficiency in order to allow for less reliance on nitrate fertilizers [22]. It has been speculated that stimulating autophagy during stress response could improve crops’ resistance to the effects of climate change [22].

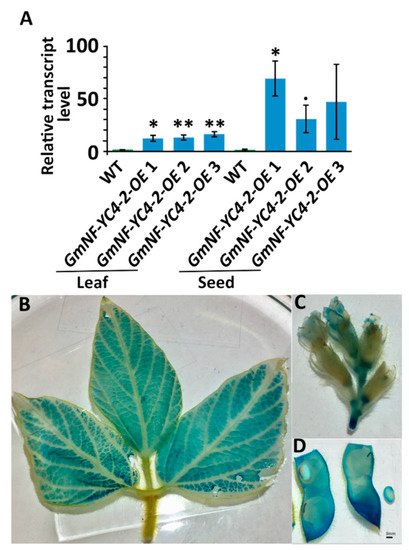

2. GmNF-YC4-2-OE Plants Have High Transcript Levels of GmNF-YC4-2 in Leaves and Seeds

To confirm the efficacy of our OE vectors, the transcript level ofGmNF-YC4-2

was assessed in leaves and seeds. The transcript level ofGmNF-YC4-2

in leaves ofGmNF-YC4-2-OE

lines ranged from 12.3-16.4 average relative quantification (RQ) compared to wild type (WT) (A). That magnitude was increased in seeds where the average RQ ranged from 31.0-69.3 (A). The validity of the 35S driven OE vectors used in this study was assessed by GUS (β-glucuronidase) staining of 35S-QQS-GUS constructs in soybean. Moderate to high levels of GUS signal were present in leaves, flowers, pods and seeds, indicating 35S activity in these tissues (Figure 1B–D) and confirming previous studies demonstrating no tissue specificity for the CaMV 35S promoter [25].

B–D) and confirming previous studies demonstrating no tissue specificity for the CaMV 35S promoter [30].

Figure 1.

GmNF-YC4-2

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

A

GmNF-YC4-2

B

C

D

n

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

p

p

•

p

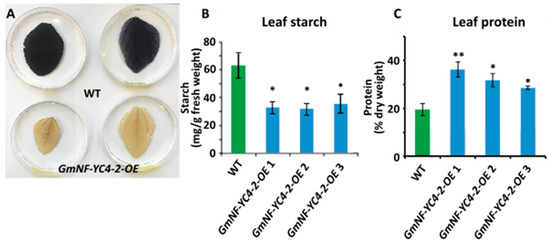

3. GmNF-YC4-2 Is Involved in Regulation of Plant Composition

Similar to previous studies inGmNF-YC4-1-OE plants [26],

plants [27],GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants also showed altered leaf and seed composition.GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants had a decrease in leaf starch (A,B,p

< 0.05 forGmNF-YC4-2-OE

1,2 andp

< 0.1 forGmNF-YC4-2-OE

3) and leaf protein content was increased (C,p

< 0.01 forGmNF-YC4-2-OE

1 andp

< 0.05 forGmNF-YC4-2-OE

2,3).

Figure 2.

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

A

B

C

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

n

C

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

p

p

•

p

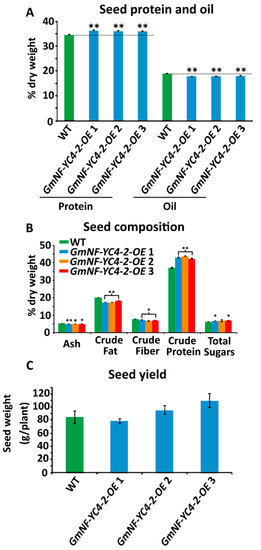

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

seeds was performed to determine if this metabolic effect in leaf tissue was unique. Near Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) analysis on seeds showed a significant increase in protein levels and decreased oil levels in three independentGmNF-YC4-2-OE

lines compared to WT plants (A,p

< 0.01 for all three lines). Chemical analysis on crushed seeds was performed to test levels of ash, crude fat, crude fiber, crude protein, and total sugars. Of these metabolites, ash (p

< 0.01, < 0.1, and < 0.05, respectively), crude fat (p

< 0.01 for all), and crude fiber (p

< 0.05 for all) showed a significant decrease in OE lines, while protein (p

< 0.01 for all) and total sugar (p

< 0.05 forGmNF-YC4-2-OE

1 and 3) levels were increased (B). In addition,GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants had an even higher seed protein content, approximately 5–10%, when compared toGmNF-YC4-1-OE

plants (,p

< 0.01). Interestingly, there was no significant difference in seed yield per plant between WT and OE plants (C). Therefore,GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants display similar metabolic alterations in both leaf and seed tissue.

Figure 3.

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

A

B

C

A

n

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

B

n

C

n

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

p

p

•

p

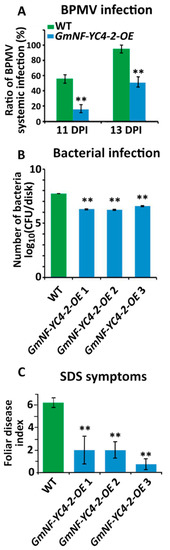

4. GmNF-YC4-2 Confers Broad Disease Resistance

To test ifGmNF-YC4-2-OE

could affect interactions between soybean and pathogens, WT and transgenic plants were inoculated with a virus, bacterium, and fungus.GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants inoculated with a recombinantBean pod mottle virus

(BPMV) expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) had reduced numbers of green fluorescent infection foci when compared to WT plants at both 11 and 13 days post inoculation (DPI) (A,p

< 0.01). TheGmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants were also infected withPseudomonas syringae

pv.glycinea

Race 4 (Psg

R4), the cause of bacterial blight. The growth of PsgR4 was decreased by 96.3%, 96.8%, and 92.8% inGmNF-YC4-2-OE 1

,GmNF-YC4-2-OE 2

, andGmNF-YC4-2-OE 3

plants compared to Williams 82 control plants (B, allp

< 0.01).

Figure 4. GmNF-YC4-2-OE

A

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

B

Psg

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

C

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

A

B

n

C

n

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

p

Fusarium virguliforme

. OE plants also displayed less severe symptoms of SDS in a field inoculation trial with a 67.8%, 67.8%, and 88.1% decrease in foliar disease index forGmNF-YC4-2-OE

1,GmNF-YC4-2-OE

2, andGmNF-YC4-2-OE

3 respectively (C, allp

< 0.01). These data show that overexpression ofGmNF-YC4-2

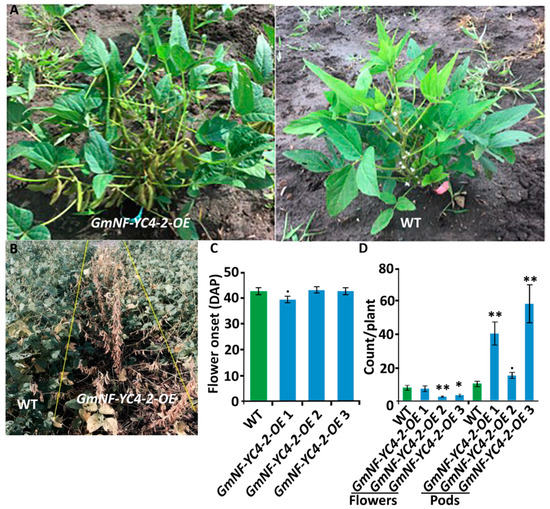

in soybean plants confers enhanced disease resistance to the viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens tested along with the altered leaf and seed composition.5. GmNF-YC4-2 Regulates Plant Maturation

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants displayed several aspects of expedited growth. In the field,

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants showed significantly faster pod development compared to the WT plants (

A). OE plants of all three lines also showed earlier senescence compared to WT (

B). As the date of flowering was similar for both WT and OE (

C), the faster maturation was seen mainly in the transition from flowering stage to pod development.

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants contained more pods than WT at 73 Days After Planting (DAP), while WT contained more flowers (

D, flowers:

p

< 0.01 for

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

2, <0.05 for

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

3; pods:

p

< 0.01

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

1 and

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

3, < 0.1 for

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

2). Thus,

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants transited quickly from flowering to pod development and this likely impacted senescence independent of flowering time. OE plants fully matured around two weeks prior to WT plants.

Figure 5.

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants transited from flowering stage to podding stage faster than WT plants. (

A

)

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants showed seeding pods while WT plants were still in the flowering stage at 77 DAP. (

B

)

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants senesced earlier than WT plants at 96 DAP. (

C

) The onset of flowering (DAP of first observed open flower) was slightly faster for

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

1 plants but similar in

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

2 and 3 plants compared to WT. (

D

) At 73 DAP, pod development for

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

plants was advanced compared to WT plants while the number of flowers was decreased. All data in bar charts show mean ± SE, (in

C

)

n

= 24 (WT), 46 (

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

1), 39 (

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

2), 26 (

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

3); (in

D

) 15 (WT), 9 (

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

1), 19 (

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

2), 11 (

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

3). A two-tailed Students t-test was used to compare

GmNF-YC4-2-OE

and WT; **

p

< 0.01, *

p

< 0.05,

•

p

< 0.1.