Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder that currently affects 1% of the population over the age of 60 years, and for which no disease-modifying treatments exist. Neurodegeneration and neuropathology in different brain areas are manifested as both motor and non-motor symptoms in patients. Recent interest in the gut–brain axis has led to increasing research into the gut microbiota changes in PD patients and their impact on disease pathophysiology. As evidence is piling up on the effects of gut microbiota in disease development and progression, another front of action has opened up in relation to the potential usage of microbiota-based therapeutic strategies in treating gastrointestinal alterations and possibly also motor symptoms in PD. This review provides status on the different strategies that are in the front line (i.e., antibiotics; probiotics; prebiotics; synbiotics; dietary interventions; fecal microbiota transplantation, live biotherapeutic products), and discusses the opportunities and challenges the field of microbiome research in PD is facing.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder that currently affects 1% of the population over the age of 60 years, and for which no disease-modifying treatments exist. Neurodegeneration and neuropathology in different brain areas are manifested as both motor and non-motor symptoms in patients. Recent interest in the gut–brain axis has led to increasing research into the gut microbiota changes in PD patients and their impact on disease pathophysiology. As evidence is piling up on the effects of gut microbiota in disease development and progression, another front of action has opened up in relation to the potential usage of microbiota-based therapeutic strategies in treating gastrointestinal alterations and possibly also motor symptoms in PD. This entry provides status on the different strategies that are in the front line (i.e., antibiotics; probiotics; prebiotics; synbiotics; dietary interventions; fecal microbiota transplantation, live biotherapeutic products), and discusses the opportunities and challenges the field of microbiome research in PD is facing.

- Parkinson’s disease

- gut microbiota

- therapeutic modulation

- gut–brain axis

- prebiotics

- probiotics

- antibiotics

- synbiotics

- Mediterranean diet

- fecal transplants

- live biotherapeutic products

1. Evidences for an Altered Gut–Brain Axis in Parkinson’s Disease

The gut–brain axis refers to the bi-directional communication between the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system (ENS) [56]. In a broader sense, it includes the neuroendocrine and neuroimmune systems, including the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis), sympathetic and parasympathetic arms of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), including the ENS and the vagus nerve, and the gut microbiota [57,58]. There is increasing evidence suggesting that gut microbiota is involved in signaling mechanisms that affect CNS neuronal circuits, thus being a modulator of brain physiology, function, communication, and even behavior. The gut microbiota includes bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses. However, evidence from comparative analyses of archea, fungi, and viruses in PD are limited. A recent report on the gut mycobiome in PD reported no differences in the fungi abundance between patients and controls [59], and another reported decreased total virus abundance in PD patients [60]. Thus, further studies are necessary to evaluate the contribution of archea/fungi/virus to PD. On the contrary, several recent and extensive reviews describe the different evidence suggesting that gut bacteria are involved in the pathophysiology of PD [61,62,63]. We do not aim to go through the same aspects but just to contextualize and briefly summarize the main findings that support the bacterial community in gut microbiota as a target for therapeutic development in PD.

1.1. Metagenomic Evidence

The use of shotgun metagenomics to carry out non-targeted sequencing of the gut microbiota community and the use of 16S rRNA gene amplicon surveys to study the bacterial and archaeal community structures have become popular and accessible techniques for clinical researchers [94][1]. These have facilitated studies in human cohorts to investigate the associations between gut microbiota dysbiosis, disruption of gut homeostasis, and CNS-related diseases such as PD [24,60,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21].

Table 1.

Different abundant taxa between Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients and healthy controls (HC).

| Phylum | Family | Genus | Increased Abundance | Decreased Abundance | References |

|---|

| Actinobacteria | 5 | 0 | [99,103,115,117,119] | [8][12][22][23][24] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Actinobacteria | Bifidobacteriaceae | 5 | 0 | [98,103,104,107,119] | [7][12][13][16][24] | |||||||||||||||||

| Actinobacteria | Bifidobacteriaceae | Bifidobacterium | 6 | 2 | [95,97, | 6 | 98, | ] | 100,102, | [7][9][11 | 107,111,119] | [4][][16][20][24] | ||||||||||

| Bacteroidetes | 2 | 5 | [95,97,99,101,104,109,119] | [4][6][8][10][13][18][24] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bacteroidetes | Prevotellaceae | 0 | 5 | [24,60,97,105,109] | [2][3][6][14][18] | |||||||||||||||||

| Bacteroidetes | Prevotellaceae | Prevotella | 3 | 5 | [24, | ] | 60, | [ | 95,98, | 3][4][7] | 100,107,110,111] | [2[9][16][19][20] | ||||||||||

| Firmicutes | 3 | 4 | [60,101,103,104,113,115,117] | [3][10][12][13][25][22][23] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Firmicutes | Enterococcaceae | 3 | 1 | [96,97,99,106] | [5][6][8][15] | |||||||||||||||||

| Firmicutes | Lachnospiraceae | 0 | 9 | [98,101,103,104, | [ | 106,107, | 10][ | 117, | 12][ | 118,119] | [7]13][15][16][23][26][24] | |||||||||||

| Firmicutes | Lachnospiraceae | Roseburia | 0 | 10 | [98,101, | ][10 | 103, | ][12 | 106, | ][15 | 107, | ][16 | 111, | ][20 | 114, | ][27 | 117, | ] | 118, | 23][26] | 119] | [7[[24] |

| Firmicutes | Lachnospiraceae | Blautia | 0 | 6 | [95,98,99,101,111,119] | [4][7][8][10][20][24] | ||||||||||||||||

| Firmicutes | Lactobacillaceae | 5 | 1 | [96,97,98,103,106,117] | [5][6][7][12][15][23] | |||||||||||||||||

| Firmicutes | Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus | 5 | 1 | [95,98,100,102,110,111] | [4][7][9][11][19][20] | ||||||||||||||||

| Firmicutes | Ruminococcaceae | 3 | 2 | [24,98,99,109,117] | [2][7][8][18][23] | |||||||||||||||||

| Firmicutes | Ruminococcaceae | Faecalibacterium | 0 | 10 | [95,97,98,99,104,111,112,114,117,118] | [4][6][7][8][13][20][21][27][23][26] | ||||||||||||||||

| Proteobacteria | 4 | 0 | [99,101,103,119] | [8][10][12][24] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Proteobacteria | Enterobacteriaceae | 6 | 0 | [24,97,,106] | [2 | 99, | ][6 | 103, | ][8][12] | 104 | [13][15] | |||||||||||

| Verrucomicrobia | 6 | 0 | [101,103,105,113,115,119] | [10][12][14][25][22][24] | ||||||||||||||||||

Verrucomicrobia | Verrucomicrobiaceae | 8 | 0 | [60,98,101, | [ | 103,105, | 7][ | 106, | 10][ | 109,119] | [3]12][14][15][18][24] | |||||||||||

| Verrucomicrobia | Verrucomicrobiaceae | Akkermansia | 13 | 0 | [60,97,98,101,103,105,109,110,] | [3] | 113, | [6] | 114, | [ | 115,118, | 7][10][12][14][18][19][25][27][22][26] | 119 | [24] |

The gut Verrucomicrobiaceae family and Akkermansia genus are beneficial bacteria that reduce gut barrier disruption and control gut permeability to maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier, although their role in neuron degeneration remains unclear [109][18]. In particular, Akkermansia muciniphila (A. muciniphila), a gram-negative bacteria located mainly in the mucus layer of the intestinal epithelium and producing mucin-degrading enzymes, that has an important role in maintaining intestinal barrier homeostasis and exerts competitive inhibition on other pathogenic bacteria that degrade the mucin [130,131][28][29]. Its abundance in the human intestinal tract is inversely correlated to several disease states such as obesity [132,133[30][31][32],134], while an increase of the relative abundance is consistently reported in PD patients [49,135][33][34]. A. muciniphila is capable of inducing a wide range of immune-modulatory responses in vitro including induction of cytokine production and activation of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 (TLR2 and TLR4) [136][35], indicating that it cannot be strictly defined as anti- or pro- inflammatory, but may instead have a more complex role in preserving the balance of the immune gut microenvironment. Nevertheless, an increased abundance of genus Akkermansia and an increased intestinal permeability in PD may expose the intestinal neural plexus directly to oxidative stress or toxins [114][27]. Thus, even if there is evidence that its presence is beneficial for normal gut function, and it is being considered a good probiotic [137[36][37],138], the maintenance of steady state levels of Akkermansia may be a pre-requisite for gut homeostasis. Enterobacteriaceae are a large family of gram-negative bacteria residing in the gut at low levels and localized closely to the mucosal epithelium [139][38]. This family is among the most commonly overgrown bacteria in many conditions involving gut inflammation [140,141][39][40] as they are responsible for the production of the endotoxins lipopolysaccharides (LPS) [142][41]. The presence of LPS disrupts gut homeostasis inducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines that may produce an inflammatory response in the CNS [143][42]. The increased levels of the families Lactobacillaceae and Bifidobacteriaceae in PD seem ironical, as they are usually well recognized as probiotics [23[43][44],144], and they are used in some clinical trials to treat constipation [145][45] and to reduce bloating and abdominal pain [146][46]. In addition, they increased the expression of tight junction proteins and upregulated mucus secretion [147][47]. However, even if they seem beneficial for the healthy population, they may act as opportunistic pathogens and cause infection in immune-compromised individuals [111,148][20][48]. Despite all the accumulated evidence, several inconsistencies exist between metagenomic studies that could be due to different experimental designs (i.e., fecal sampling, DNA extraction protocols, targeted 16S marker gene regions, statistical analysis) and/or patient enrollment criteria (i.e., ethnic origins, host genetics, geography, diet, lifestyle, and other confounding factors). These discrepancies make it difficult to reach a general agreement and determine which is the PD dysbiotic profile and which are the exact alterations in metabolic pathways [49,149][33][49].

2. Targeting the Gut–Brain Axis in PD

Because of the accumulating evidence from human and animal studies showing gut microbiota alterations in PD, several research groups are working in the identification of specific microbes and the pathways that connect them to the brain. Considering how much easier it is to manipulate the gut than the brain, the possibility to modulate the manifestation of PD symptoms by changing the gut microbiota is attracting a lot of attention both from the academic and pharmaceutical sectors. Much work is still needed given the complexity of the gut–brain axis, but many believe in the therapeutic potential of gut microbiota, and evidence is slowly coming out.

2.1. Antibiotics

Antibiotics are chemical substances that at low concentrations can inhibit or eliminate some microorganisms. They have attracted a lot of interest because some have other biological actions in the CNS that are independent from their anti-microbial activity such as anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, or α-syn anti-aggregation effects [202,203,204]. Those characteristics can be of crucial importance to design PD or other neurodegenerative diseases’ treatments. The new challenge is to uncover the mechanisms of these compounds and elucidate how they interact with CNS function. Since many are already approved by regulatory agencies for use in humans, the process of getting into clinical trials would be significantly accelerated [205,206]. However, the usage of antibiotics can alter the relative abundance of bacterial species causing the disappearance of some and the appearance and growth of new bacterial species, thus essentially leading to dysbiosis [207]. Thus, it is important to understand the biology, the properties, and the relations between the coexisting species and how they interact with the host to be able to design new therapeutic approaches while preserving and protecting the beneficial bacteria of our gut microbiota [208].

Antibiotics are chemical substances that at low concentrations can inhibit or eliminate some microorganisms. They have attracted a lot of interest because some have other biological actions in the CNS that are independent from their anti-microbial activity such as anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, or α-syn anti-aggregation effects [50][51][52]. Those characteristics can be of crucial importance to design PD or other neurodegenerative diseases’ treatments. The new challenge is to uncover the mechanisms of these compounds and elucidate how they interact with CNS function. Since many are already approved by regulatory agencies for use in humans, the process of getting into clinical trials would be significantly accelerated [53][54]. However, the usage of antibiotics can alter the relative abundance of bacterial species causing the disappearance of some and the appearance and growth of new bacterial species, thus essentially leading to dysbiosis [55]. Thus, it is important to understand the biology, the properties, and the relations between the coexisting species and how they interact with the host to be able to design new therapeutic approaches while preserving and protecting the beneficial bacteria of our gut microbiota [56].

2.2 Probiotics

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit to the host [236]. Increasing evidence supports the idea of using certain probiotics to modulate gut microbiota and its functions in order to prevent dysbiosis or to have a positive impact into the host health. Most of the commercially available probiotics contain

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit to the host [57]. Increasing evidence supports the idea of using certain probiotics to modulate gut microbiota and its functions in order to prevent dysbiosis or to have a positive impact into the host health. Most of the commercially available probiotics contain

Lactobacillus

,

Bifidobacterium

, or

Saccharomyces spp. [23]. Several studies in vitro and in vivo with animal models and humans’ preclinical trials demonstrated the potential benefits of probiotics in the prevention or treatment of GI disorders such as chronic inflammation or inflammatory bowel disease [237,238,239]. Interestingly, in the last 10 years, several studies reported that probiotics also have an influence in the CNS by showing efficacy in improving psychiatric disorder behaviors such as depression, anxiety or cognitive symptoms [240,241,242]. This evidence encouraged the field to test them for PD as they might be a powerful tool to modulate PD associated dysbiosis and improve GI dysfunction [63,243]. However, pre-clinical or clinical evidence on the beneficial effects of probiotics in PD is still very limited.

spp. [43]. Several studies in vitro and in vivo with animal models and humans’ preclinical trials demonstrated the potential benefits of probiotics in the prevention or treatment of GI disorders such as chronic inflammation or inflammatory bowel disease [58][59][60]. Interestingly, in the last 10 years, several studies reported that probiotics also have an influence in the CNS by showing efficacy in improving psychiatric disorder behaviors such as depression, anxiety or cognitive symptoms [61][62][63]. This evidence encouraged the field to test them for PD as they might be a powerful tool to modulate PD associated dysbiosis and improve GI dysfunction [64][65]. However, pre-clinical or clinical evidence on the beneficial effects of probiotics in PD is still very limited.

2.3 Prebiotics

Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients that beneficially affect the host’s health by selectively stimulating the growth and/or activity of some genera of microorganisms [

,

]. Prebiotic definitions are generally attributed to dietary fibers (oligo and polysaccharides substrates) that are really important as most gut microbiota degrade dietary fibers to obtain energy for their own growth [

]. For instance, they are the main source of energy for Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus [

]. However, as the complexity and function of gut microbial ecosystems is being unveiled, new microbial groups or species of interest for health purposes are being identified, and new research is also focused on the use of fructans, galacto-oligosaccharides, and lactulose for their benefits into the gut microbiota [

]. Prebiotics largely impact the composition of the gut microbiota and its metabolic activity, thus improving stool quality, reducing gut infections, improving bowel motility and general well-being [

,

]. Hence, it is relevant to study the beneficial effects they might have in GI dysfunction related with inflammatory processes and constipation [

] and that directly affect PD patients gut microbiota.

2.4. Synbiotics

Synbiotics are described to be a combination of synergistically acting probiotics and prebiotics, where a prebiotic component selectively favors the metabolism or growth of a probiotic microorganisms, thus providing a beneficial effect to the host’s health [282,283]. Synbiotics should be created in appropriate combination in order to overcome possible difficulties in the survival of probiotics in the GI tract. Moreover, the combination of both should have a superior effect in the host health compared to the activity that they may have alone [275].

Synbiotics are described to be a combination of synergistically acting probiotics and prebiotics, where a prebiotic component selectively favors the metabolism or growth of a probiotic microorganisms, thus providing a beneficial effect to the host’s health [66][67]. Synbiotics should be created in appropriate combination in order to overcome possible difficulties in the survival of probiotics in the GI tract. Moreover, the combination of both should have a superior effect in the host health compared to the activity that they may have alone [68].

2.5. Dietary Interventions

Our knowledge on the substances that can influence gut microbiota and their colonizing abilities has improved significantly in the past years. Therefore, another approach that can be used to modulate these microbial population is dietary intervention. Moreover, we can use specific nutrient combinations containing membrane phosphatide precursors such as uridine and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [287,288] together with cofactors, prebiotics, probiotics, or antibiotics in order to reduce barrier-related pathologies in the ENS and CNS, neuroinflammation, neurodegenerative processes, etc. [289]. This approach can also complement the traditional PD therapies and confer clinical benefits to PD patients since they might modulate motor and non-motor symptoms.

Our knowledge on the substances that can influence gut microbiota and their colonizing abilities has improved significantly in the past years. Therefore, another approach that can be used to modulate these microbial population is dietary intervention. Moreover, we can use specific nutrient combinations containing membrane phosphatide precursors such as uridine and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [69][70] together with cofactors, prebiotics, probiotics, or antibiotics in order to reduce barrier-related pathologies in the ENS and CNS, neuroinflammation, neurodegenerative processes, etc. [71]. This approach can also complement the traditional PD therapies and confer clinical benefits to PD patients since they might modulate motor and non-motor symptoms.

2.5.1. Mediterranean Diet

Mediterranean diet, which is based in the daily consumption of vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, whole grains, and healthy fats, can beneficially impact the brain by multiple mechanisms. On the contrary, the Western diet is known for high amounts of fat and sugar and low intake of dietary fibers. Thus, the microbiome of people having a Mediterranean diet is characterized by the abundance of bacteria that uses dietary fiber to produce SCFA [290]. As mentioned previously, SCFA are the end-products of fermentation of non-digestible carbohydrates by gut microbiota, and they are really important for intestinal barrier function, gene expression, and mitochondrial function. In Western diets, where dietary fiber ingestion is low, the microbiota uses protein as an energy source [291]. SCFA-producing bacteria may be reduced and the growth of gram-negative bacteria may be favored, thus causing dysbiosis and an increase of LPS [292,293]. Mediterranean diet is associated with a lower incidence and progression of PD, although further studies are needed to elucidate the potential causality of this association as well as the underlying neurobiological mechanisms. Still, one could speculate that the Mediterranean diet has a suggestive protective effect on PD risk, in a way that promotes SCFA production and anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory actions, thus maintaining a healthy microbiota profile contributing to GI homeostasis. In any case, there is not enough evidence yet to understand the exact type and quantity of individual food components required for effective neuroprotection and which are the exact mechanisms involved. Overall, these data provide a strong rationale for conducting randomized controlled dietary trials in prodromal and manifest PD patients to determine whether a Mediterranean diet can modulate gut microbiota composition and impact disease course [300].

Mediterranean diet, which is based in the daily consumption of vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, whole grains, and healthy fats, can beneficially impact the brain by multiple mechanisms. On the contrary, the Western diet is known for high amounts of fat and sugar and low intake of dietary fibers. Thus, the microbiome of people having a Mediterranean diet is characterized by the abundance of bacteria that uses dietary fiber to produce SCFA [72]. As mentioned previously, SCFA are the end-products of fermentation of non-digestible carbohydrates by gut microbiota, and they are really important for intestinal barrier function, gene expression, and mitochondrial function. In Western diets, where dietary fiber ingestion is low, the microbiota uses protein as an energy source [73]. SCFA-producing bacteria may be reduced and the growth of gram-negative bacteria may be favored, thus causing dysbiosis and an increase of LPS [74][75]. Mediterranean diet is associated with a lower incidence and progression of PD, although further studies are needed to elucidate the potential causality of this association as well as the underlying neurobiological mechanisms. Still, one could speculate that the Mediterranean diet has a suggestive protective effect on PD risk, in a way that promotes SCFA production and anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory actions, thus maintaining a healthy microbiota profile contributing to GI homeostasis. In any case, there is not enough evidence yet to understand the exact type and quantity of individual food components required for effective neuroprotection and which are the exact mechanisms involved. Overall, these data provide a strong rationale for conducting randomized controlled dietary trials in prodromal and manifest PD patients to determine whether a Mediterranean diet can modulate gut microbiota composition and impact disease course [76].

2.5.2. Omega-3 Fatty Acids

In addition to the benefits of SCFAs, several studies have reported that polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), especially omega (n)-3 (n-3 PUFAs), are essential in the human diet. There are three main types of n-3 PUFAs including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), DHA and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) [301], which are important structural components in cell membranes. N-3 PUFAs are present in high quantities in fish, especially cold-water fatty fish, such as salmon, mackerel, tuna, herring, and sardines; moreover, they can be found as purified supplements [302].

In addition to the benefits of SCFAs, several studies have reported that polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), especially omega (n)-3 (n-3 PUFAs), are essential in the human diet. There are three main types of n-3 PUFAs including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), DHA and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) [77], which are important structural components in cell membranes. N-3 PUFAs are present in high quantities in fish, especially cold-water fatty fish, such as salmon, mackerel, tuna, herring, and sardines; moreover, they can be found as purified supplements [78].

2.5.3. Vitamins

Food rich in vitamins has also gained attention in the treatments and prevention strategies for PD. Since oxidative stress plays an important role in neurodegeneration and PD, vitamins such as vitamin B, C, and E may prevent, delay, or alleviate the clinical symptoms of PD related with oxidative stress, free radical formation, and neuroinflammation [316,317].

Food rich in vitamins has also gained attention in the treatments and prevention strategies for PD. Since oxidative stress plays an important role in neurodegeneration and PD, vitamins such as vitamin B, C, and E may prevent, delay, or alleviate the clinical symptoms of PD related with oxidative stress, free radical formation, and neuroinflammation [79][80].

2.6. Fecal Microbiota Transplant (FMT)

FMT is the process of delivering fecal material from healthy donors to recipient patients with a disease related to an unhealthy gut microbiome in order to re-establish a stable gut microbiota [327]. FMT has shown a high amount of success in the short-term treatment of

FMT is the process of delivering fecal material from healthy donors to recipient patients with a disease related to an unhealthy gut microbiome in order to re-establish a stable gut microbiota [81]. FMT has shown a high amount of success in the short-term treatment of

Clostridium difficile infections, together with low-risk and short-term adverse effects, most commonly bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea and/or constipation [328,329]. During the last 10 years, there is an increasing interest on the benefits of FMT in GI diseases (i.e., inflammatory bowel syndrome [330]) but also in other diseases where the GI tract is thought to play a role. In the case of neurological disorders, treatments with FMT are limited although there are case reports that it is effective in the treatment of autism [53], multiple sclerosis [331], chronic fatigue syndrome [332], anxiety [333], depression [334], among others.

infections, together with low-risk and short-term adverse effects, most commonly bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea and/or constipation [82][83]. During the last 10 years, there is an increasing interest on the benefits of FMT in GI diseases (i.e., inflammatory bowel syndrome [84]) but also in other diseases where the GI tract is thought to play a role. In the case of neurological disorders, treatments with FMT are limited although there are case reports that it is effective in the treatment of autism [85], multiple sclerosis [86], chronic fatigue syndrome [87], anxiety [88], depression [89], among others.

2.7. Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs)

Apart from the already mentioned classical approaches for modulating gut microbiota (i.e., antibiotics, probiotics, prebiotics, dietary compounds, and FMT), there are new challenges and opportunities in order to modulate the structure and function of gut microbiota from a therapeutic point of view. Microbes can be engineered to act like living therapeutic factories designed and developed to perform specific actions in the human body in order to treat, cure or prevent a disease, infections or disorders [341]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defined LBPs as living organisms, which does not include vaccines, viruses, or oncolytic bacteria, which are applicable to the prevention, treatment, or cure of a disease or condition. LBPs are distinguished from probiotic supplements as most probiotics are regulated as dietary supplements and cannot make claims to treat or prevent disease. However, some probiotics can also fit in the LBP definition. Other LBPs can include recombinant LBPs that are genetically modified organisms that have been engineered by adding, deleting, or altering genetic material within the organism [342].

Apart from the already mentioned classical approaches for modulating gut microbiota (i.e., antibiotics, probiotics, prebiotics, dietary compounds, and FMT), there are new challenges and opportunities in order to modulate the structure and function of gut microbiota from a therapeutic point of view. Microbes can be engineered to act like living therapeutic factories designed and developed to perform specific actions in the human body in order to treat, cure or prevent a disease, infections or disorders [90]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defined LBPs as living organisms, which does not include vaccines, viruses, or oncolytic bacteria, which are applicable to the prevention, treatment, or cure of a disease or condition. LBPs are distinguished from probiotic supplements as most probiotics are regulated as dietary supplements and cannot make claims to treat or prevent disease. However, some probiotics can also fit in the LBP definition. Other LBPs can include recombinant LBPs that are genetically modified organisms that have been engineered by adding, deleting, or altering genetic material within the organism [91].

3. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Unprecedented breakthroughs in microbiome research have been achieved in the past 15 years. In line with this exciting new field in biomedical research, the gut microbiota has become an increasingly attractive research area in the quest to better understand the pathogenesis of PD and several studies have shown that PD patients have abnormal gut microbiota. Current studies should aim at clarifying the role of gut dysbiosis in PD development and progression. The future looks promising as we begin to recognize the specific strains and mechanisms underlying the effects of gut dysbiosis, and, as we see, the first attempts of clinical application in PD (

). However, there are still major limitations and challenges that the research community needs to address, especially regarding the definition of those specific strains that are directly related to PD pathogenesis independently of other co-variables (i.e., age, sex, ethnicity, geography, diet, lifestyle, medication), the mechanistic understanding of host–microbiome interactions and the integration of these insights into routine clinical practice. Then, mechanistically focused microbiome research aimed at demonstrating causality rather than association or correlation is a must before microbiome-derived data can really be incorporated into precision medicine.

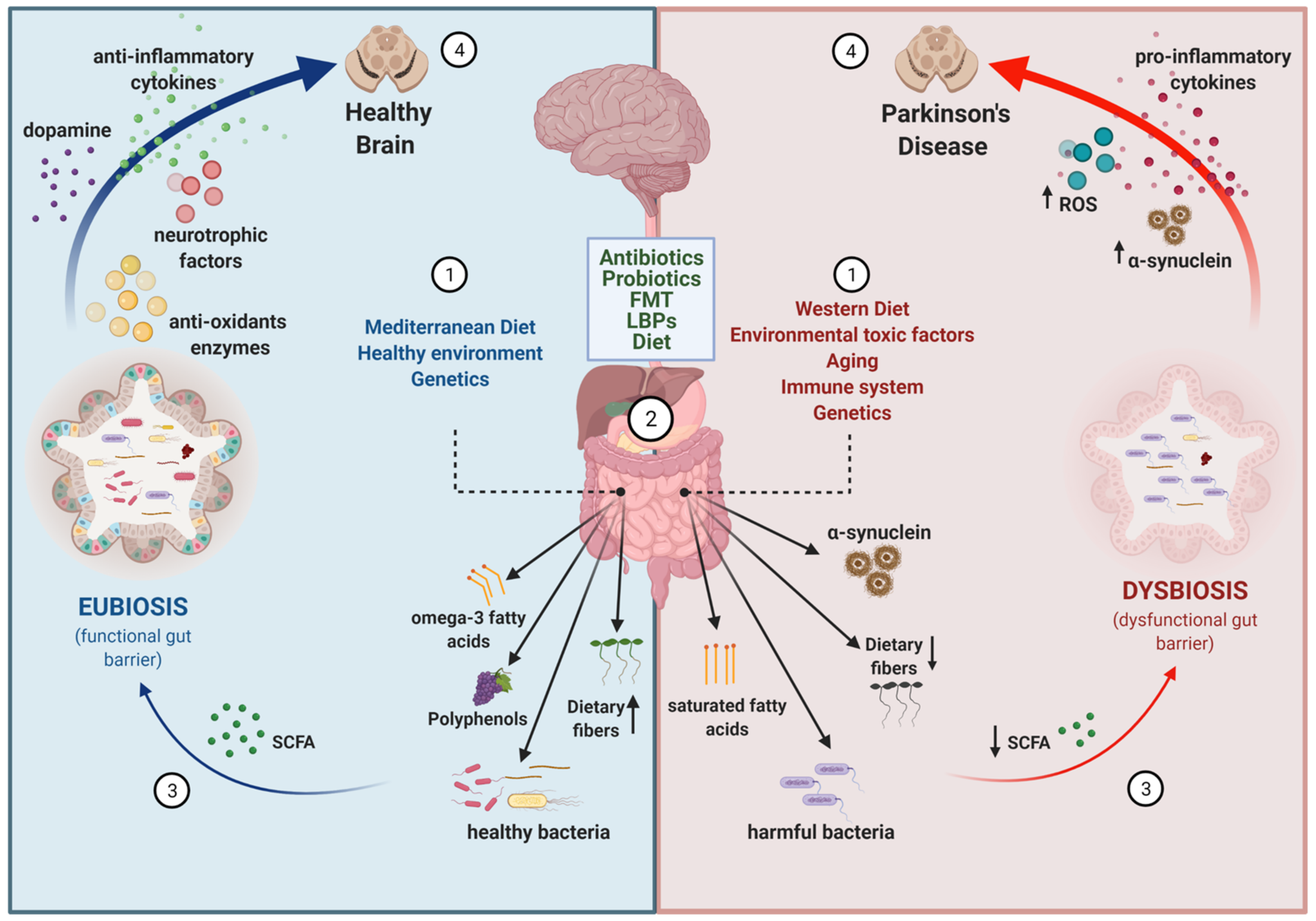

Figure 1.

Disease-modifying strategies based on the gut microbiota. (1) The gut microbiota composition is influenced by several intrinsic (i.e., genetics, aging and immune system function) and extrinsic factors, including dietary habits (e.g., Mediterranean diet vs. Western diet) and environmental conditions (e.g., healthy environment vs pesticides/polluted environment). (2) Several strategies can be used to modify the composition of the gut microbiota to revert a dysbiotic condition: antibiotics, probiotics, fecal microbiota transplants (FMT), live biotherapeutic products (LBP), and dietary factors. (3) As a result, the balance between healthy/harmful bacteria, the presence of dietary fibers, the levels of metabolites with anti/pro-oxidant and anti/pro-inflammatory properties (e.g., omega-3 fatty acids, polyphenols, short chain fatty acids (SCFA), saturated fatty acids), and the aggregation of proteins like α-synuclein in the gut will be modified. (4) Because of the existing communication between the gut and the brain, these changes in the gut may have a direct impact on brain function through different mechanisms: levels of neurotransmitters, cytokines, reactive oxygen species (ROS), neurotrophic factors, and aggregation of α-synuclein. Overall, changes of the gut microbiota composition can have a beneficial or detrimental impact on the neurodegenerative process occurring in Parkinson’s disease.

With this in mind, the opportunities microbiome research is offering the field are extraordinary. First, gut microbiota might represent a unique source for the development of pathophysiology-based therapies. If gut dysbiosis contributes to neurodegeneration and the manifestation of PD-symptoms, a therapeutic approach aiming to reestablish a healthy microbiota seems appropriate. Different strategies can be envisioned: lowering the abundance of certain pathogenic or detrimental strains with selective antimicrobials, repopulating the gut microbiome with alternate bacterial strains (such as with probiotics), or exploring the potential roles of selective FMT. Although preclinical and clinical evidence on these beneficial effects in PD is still very limited, examples from other neurological diseases are encouraging [353,354,355,356]. In addition, the interest in FMT is exemplified by more than 350 completed or planned clinical trials (NIH, December 2020). However, yet again, we need to identify the mechanisms underlying the reported effects of FMT and probiotics in order to move towards more controllable and potent precision interventions. In addition, defining the right time for intervention and the appropriate regime (continuous use vs long-term effects) will also be major challenges in the next few years.

With this in mind, the opportunities microbiome research is offering the field are extraordinary. First, gut microbiota might represent a unique source for the development of pathophysiology-based therapies. If gut dysbiosis contributes to neurodegeneration and the manifestation of PD-symptoms, a therapeutic approach aiming to reestablish a healthy microbiota seems appropriate. Different strategies can be envisioned: lowering the abundance of certain pathogenic or detrimental strains with selective antimicrobials, repopulating the gut microbiome with alternate bacterial strains (such as with probiotics), or exploring the potential roles of selective FMT. Although preclinical and clinical evidence on these beneficial effects in PD is still very limited, examples from other neurological diseases are encouraging [92][93][94][95]. In addition, the interest in FMT is exemplified by more than 350 completed or planned clinical trials (NIH, December 2020). However, yet again, we need to identify the mechanisms underlying the reported effects of FMT and probiotics in order to move towards more controllable and potent precision interventions. In addition, defining the right time for intervention and the appropriate regime (continuous use vs long-term effects) will also be major challenges in the next few years.

Second, gut microbiota might represent a unique source for biomarkers relevant to early/prodromal disease phases, to predict the in vivo L-Dopa bioavailability and efficacy, and to assess the impact of therapeutic approaches in PD patients. Overall, biomarkers that ultimately will improve the management of the disease. However, for metagenomic studies to be meaningful, the research community should standardize study designs in order to minimize variations due to different sources of technical and biological variability. Moreover, sequencing platforms are currently not available in all medical centers and their implementation into clinical care will require some efforts in sample processing and data analysis to render them clinically interpretable and affordable. Research on additional biomarkers related to gut microbiota dysbiosis not relying on abundance of phyla/families/genera/species of gut bacteria, hold great promise. In this sense, integrated multiomic analyses for functional interrogation of microbiome–host interactions will be very revealing. To have objective measures, a part from clinical scales and questionnaires, to assess the safety and efficacy of different therapeutic interventions in clinical trials, is fundamental.

Finally, gut microbiota might represent a new approach for personalized medicine. Recent studies identifying the bacteria that metabolize L-Dopa to dopamine (

Enterococcus faecalis

) and m-tyramine (

Eggerthella lenta) have highlighted the benefits of screening patients in order to anticipate those with a deleterious metabolism of L-Dopa in the gut and treat them with small molecule inhibitors to prevent TDC-dependent L-Dopa decarboxylation in the gut. Such discoveries offer a unique potential to personalize L-Dopa treatment in the hope of ameliorating the variability of L-Dopa bioavailability and motor fluctuations. In addition, the field of machine learning (ML) offers unprecedented opportunities for the field of PD. ML includes the development and application of computer algorithms that improve with experience, thus representing appropriate tools to build predictive models for the classification of biological data and identify biomarkers through a training procedure [357]. A recent study processed 846 16S rRNA microbiota published datasets coming from six different studies and applied an ML approach to define a classifier that could predict the pathological status of PD patients against HC. Moreover, they identified a subset of 22 bacterial families that were discriminative for the prediction, and, interestingly, not all families identified by the algorithm were reported in the literature. The identification of new bacterial families that may play an important role in predicting PD status highlights the power of a prediction analysis based on ML algorithms [358]. Importantly, the success of this type of approach is dependent on the willingness of the research community to apply honest data sharing policies.

) have highlighted the benefits of screening patients in order to anticipate those with a deleterious metabolism of L-Dopa in the gut and treat them with small molecule inhibitors to prevent TDC-dependent L-Dopa decarboxylation in the gut. Such discoveries offer a unique potential to personalize L-Dopa treatment in the hope of ameliorating the variability of L-Dopa bioavailability and motor fluctuations. In addition, the field of machine learning (ML) offers unprecedented opportunities for the field of PD. ML includes the development and application of computer algorithms that improve with experience, thus representing appropriate tools to build predictive models for the classification of biological data and identify biomarkers through a training procedure [96]. A recent study processed 846 16S rRNA microbiota published datasets coming from six different studies and applied an ML approach to define a classifier that could predict the pathological status of PD patients against HC. Moreover, they identified a subset of 22 bacterial families that were discriminative for the prediction, and, interestingly, not all families identified by the algorithm were reported in the literature. The identification of new bacterial families that may play an important role in predicting PD status highlights the power of a prediction analysis based on ML algorithms [97]. Importantly, the success of this type of approach is dependent on the willingness of the research community to apply honest data sharing policies.

In conclusion, albeit further studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms of gut dysbiosis in PD pathogenesis and to better define the clinical outcomes and safety issues, the potential usage of microbiota-based therapeutic strategies in treating GI alterations, and possibly also motor symptoms, is definitely in the spotlight, and we will be expectant to the new data coming from microbiome studies and clinical trials.

In conclusion, albeit further studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms of gut dysbiosis in PD pathogenesis and to better define the clinical outcomes and safety issues, the potential usage of microbiota-based therapeutic strategies in treating GI alterations, and possibly also motor symptoms, is definitely in the spotlight, and we will be expectant to the new data coming from microbiome studies and clinical trials.

References

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The gut-brain axis: Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 203–209.

- Liu, L.; Zhu, G. Gut–Brain Axis and Mood Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 223.

- Bonaz, B.; Bazin, T.; Pellissier, S. The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 49.

- Cirstea, M.S.; Sundvick, K.; Golz, E.; Yu, A.C.; Boutin, R.C.T.; Kliger, D.; Finlay, B.B.; Appel-Cresswell, S. The gut mycobiome in Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 2021, 11, 153–158.

- Bedarf, J.R.; Hildebrand, F.; Coelho, L.P.; Sunagawa, S.; Bahram, M.; Goeser, F.; Bork, P.; Wüllner, U. Functional implications of microbial and viral gut metagenome changes in early stage L-DOPA-naïve Parkinson’s disease patients. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 39.

- Haikal, C.; Chen, Q.Q.; Li, J.Y. Microbiome changes: An indicator of Parkinson’s disease? Transl. Neurodegener. 2019, 8, 38.

- Scheperjans, F.; Derkinderen, P.; Borghammer, P. The gut and Parkinson’s disease: Hype or hope? J. Parkinsons Dis. 2018, 8, S31–S39.

- Parashar, A.; Udayabanu, M. Gut microbiota: Implications in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2017, 38, 1–7.

- Fraher, M.H.; O’Toole, P.W.; Quigley, E.M.M. Techniques used to characterize the gut microbiota: A guide for the clinician. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 9, 312–322.

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 350–358.

- Petrov, V.A.; Saltykova, I.V.; Zhukova, I.A.; Alifirova, V.M.; Zhukova, N.G.; Dorofeeva, Y.B.; Tyakht, A.V.; Kovarsky, B.A.; Alekseev, D.G.; Kostryukova, E.S.; et al. Analysis of gut microbiota in patients with parkinson’s disease. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 162, 734–737.

- Hopfner, F.; Künstner, A.; Müller, S.H.; Künzel, S.; Zeuner, K.E.; Margraf, N.G.; Deuschl, G.; Baines, J.F.; Kuhlenbäumer, G. Gut microbiota in Parkinson disease in a northern German cohort. Brain Res. 2017, 1667, 41–45.

- Unger, M.M.; Spiegel, J.; Dillmann, K.U.; Grundmann, D.; Philippeit, H.; Bürmann, J.; Faßbender, K.; Schwiertz, A.; Schäfer, K.H. Short chain fatty acids and gut microbiota differ between patients with Parkinson’s disease and age-matched controls. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 32, 66–72.

- Hill-Burns, E.M.; Debelius, J.W.; Morton, J.T.; Wissemann, W.T.; Lewis, M.R.; Wallen, Z.D.; Peddada, S.D.; Factor, S.A.; Molho, E.; Zabetian, C.P.; et al. Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 739–749.

- Li, W.; Wu, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, T.; Liang, S.; Duan, Y.; Jin, F.; Qin, B. Structural changes of gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease and its correlation with clinical features. Sci China Life Sci 2017, 60, 1223–1233.

- Hasegawa, S.; Goto, S.; Tsuji, H.; Okuno, T.; Asahara, T.; Nomoto, K.; Shibata, A.; Fujisawa, Y.; Minato, T.; Okamoto, A.; et al. Intestinal dysbiosis and lowered serum lipopolysaccharide-binding protein in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142164.

- Keshavarzian, A.; Green, S.J.; Engen, P.A.; Voigt, R.M.; Naqib, A.; Forsyth, C.B.; Mutlu, E.; Shannon, K.M. Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1351–1360.

- Qian, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Wu, C.; Song, Y.; Qin, N.; Chen, S.D.; Xiao, Q. Alteration of the fecal microbiota in Chinese patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2018, 70, 194–202.

- Barichella, M.; Severgnini, M.; Cilia, R.; Cassani, E.; Bolliri, C.; Caronni, S.; Ferri, V.; Cancello, R.; Ceccarani, C.; Faierman, S.; et al. Unraveling gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 396–405.

- Lin, A.; Zheng, W.; He, Y.; Tang, W.; Wei, X.; He, R.; Huang, W.; Su, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H.; et al. Gut microbiota in patients with Parkinson’s disease in southern China. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 53, 82–88.

- Heintz-Buschart, A.; Pandey, U.; Wicke, T.; Sixel-Döring, F.; Janzen, A.; Sittig-Wiegand, E.; Trenkwalder, C.; Oertel, W.H.; Mollenhauer, B.; Wilmes, P. The nasal and gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease and idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 88–98.

- Pietrucci, D.; Cerroni, R.; Unida, V.; Farcomeni, A.; Pierantozzi, M.; Mercuri, N.B.; Biocca, S.; Stefani, A.; Desideri, A. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in a selected population of Parkinson’s patients. Park. Relat. Disord. 2019, 65, 124–130.

- Aho, V.T.E.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Voutilainen, S.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Auvinen, P.; Scheperjans, F. Gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease: Temporal stability and relations to disease progression. EBioMedicine 2019, 44, 691–707.

- Lin, C.H.; Chen, C.C.; Chiang, H.L.; Liou, J.M.; Chang, C.M.; Lu, T.P.; Chuang, E.Y.; Tai, Y.C.; Cheng, C.; Lin, H.Y.; et al. Altered gut microbiota and inflammatory cytokine responses in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16.

- Li, F.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Sui, X.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J. Alteration of the fecal microbiota in North-Eastern Han Chinese population with sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 707, 134297.

- Li, C.; Cui, L.; Yang, Y.; Miao, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Cui, G.; Zhang, Y. Gut microbiota differs between parkinson’s disease patients and healthy controls in northeast China. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12.

- Wallen, Z.D.; Appah, M.; Dean, M.N.; Sesler, C.L.; Factor, S.A.; Molho, E.; Zabetian, C.P.; Standaert, D.G.; Payami, H. Characterizing dysbiosis of gut microbiome in PD: Evidence for overabundance of opportunistic pathogens. NPJ Park. Dis. 2020, 6, 1–12.

- Weis, S.; Schwiertz, A.; Unger, M.M.; Becker, A.; Faßbender, K.; Ratering, S.; Kohl, M.; Schnell, S.; Schäfer, K.-H.; Egert, M. Effect of Parkinson’s disease and related medications on the composition of the fecal bacterial microbiota. NPJ Park. Dis. 2019, 5, 28.

- Zhang, F.; Yue, L.; Fang, X.; Wang, G.; Li, C.; Sun, X.; Jia, X.; Yang, J.; Song, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Altered gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease patients/healthy spouses and its association with clinical features. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 81, 84–88.

- Cilia, R.; Piatti, M.; Cereda, E.; Bolliri, C.; Caronni, S.; Ferri, V.; Cassani, E.; Bonvegna, S.; Ferrarese, C.; Zecchinelli, A.L.; et al. Does Gut Microbiota Influence the Course of Parkinson’s Disease? A 3-Year Prospective Exploratory Study in de novo Patients. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2020, 1–12, Preprint.

- Vascellari, S.; Palmas, V.; Melis, M.; Pisanu, S.; Cusano, R.; Uva, P.; Perra, D.; Madau, V.; Sarchioto, M.; Oppo, V.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Metabolome Alterations Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. mSystems 2020, 5.

- Qian, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Huang, P.; Li, B.; Du, J.; He, Y.; Su, B.; Xu, L.M.; Wang, L.; et al. Gut metagenomics-derived genes as potential biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2020, 143, 2474–2489.

- Nishiwaki, H.; Hamaguchi, T.; Ito, M.; Ishida, T.; Maeda, T.; Kashihara, K.; Tsuboi, Y.; Ueyama, J.; Shimamura, T.; Mori, H.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acid-Producing Gut Microbiota Is Decreased in Parkinson’s Disease but Not in Rapid-Eye-Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder. mSystems 2020, 5.

- Nishiwaki, H.; Ito, M.; Ishida, T.; Hamaguchi, T.; Maeda, T.; Kashihara, K.; Tsuboi, Y.; Ueyama, J.; Shimamura, T.; Mori, H.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Gut Dysbiosis in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1626–1635.

- Collado, M.C.; Derrien, M.; Isolauri, E.; De Vos, W.M.; Salminen, S. Intestinal integrity and Akkermansia muciniphila, a mucin-degrading member of the intestinal microbiota present in infants, adults, and the elderly. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 7767–7770.

- Van Passel, M.W.J.; Kant, R.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Plugge, C.M.; Derrien, M.; Malfatti, S.A.; Chain, P.S.G.; Woyke, T.; Palva, A.; de Vos, W.M.; et al. The genome of Akkermansia muciniphila, a dedicated intestinal mucin degrader, and its use in exploring intestinal metagenomes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16876.

- Xu, Y.; Wang, N.; Tan, H.Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y. Function of Akkermansia muciniphila in Obesity: Interactions With Lipid Metabolism, Immune Response and Gut Systems. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 219.

- Geerlings, S.; Kostopoulos, I.; de Vos, W.; Belzer, C. Akkermansia muciniphila in the Human Gastrointestinal Tract: When, Where, and How? Microorganisms 2018, 6, 75.

- Everard, A.; Belzer, C.; Geurts, L.; Ouwerkerk, J.P.; Druart, C.; Bindels, L.B.; Guiot, Y.; Derrien, M.; Muccioli, G.G.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9066–9071.

- Boertien, J.M.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Aho, V.T.E.; Scheperjans, F. Increasing Comparability and Utility of Gut Microbiome Studies in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2019, 9, S297–S312.

- Gerhardt, S.; Mohajeri, M.H. Changes of colonic bacterial composition in parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients 2018, 10, 708.

- Ottman, N.; Reunanen, J.; Meijerink, M.; Pietilä, T.E.; Kainulainen, V.; Klievink, J.; Huuskonen, L.; Aalvink, S.; Skurnik, M.; Boeren, S.; et al. Pili-like proteins of Akkermansia muciniphila modulate host immune responses and gut barrier function. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173004.

- ZHOU, J.C.; ZHANG, X.W. Akkermansia muciniphila: A promising target for the therapy of metabolic syndrome and related diseases. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2019, 17, 835–841.

- Zhang, T.; Li, Q.; Cheng, L.; Buch, H.; Zhang, F. Akkermansia muciniphila is a promising probiotic. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 1109–1125.

- Zeng, M.Y.; Inohara, N.; Nuñez, G. Mechanisms of inflammation-driven bacterial dysbiosis in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 18–26.

- Lupp, C.; Robertson, M.L.; Wickham, M.E.; Sekirov, I.; Champion, O.L.; Gaynor, E.C.; Finlay, B.B. Host-Mediated Inflammation Disrupts the Intestinal Microbiota and Promotes the Overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe 2007, 2, 119–129.

- Menezes-Garcia, Z.; Do Nascimento Arifa, R.D.; Acúrcio, L.; Brito, C.B.; Gouvea, J.O.; Lima, R.L.; Bastos, R.W.; Fialho Dias, A.C.; Antunes Dourado, L.P.; Bastos, L.F.S.; et al. Colonization by Enterobacteriaceae is crucial for acute inflammatory responses in murine small intestine via regulation of corticosterone production. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 1531–1546.

- Rhee, S.H. Lipopolysaccharide: Basic Biochemistry, Intracellular Signaling, and Physiological Impacts in the Gut. Intest. Res. 2014, 12, 90.

- Zhao, J.; Bi, W.; Xiao, S.; Lan, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Lu, D.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment in mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12.

- Dutta, S.K.; Verma, S.; Jain, V.; Surapaneni, B.K.; Vinayek, R.; Phillips, L.; Nair, P.P. Parkinson’s disease: The emerging role of gut dysbiosis, antibiotics, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019, 25, 363–376.

- Gareau, M.G.; Sherman, P.M.; Walker, W.A. Probiotics and the gut microbiota in intestinal health and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 7, 503–514.

- Cassani, E.; Privitera, G.; Pezzoli, G.; Pusani, C.; Madio, C.; Iorio, L.; Barichella, M. Use of probiotics for the treatment of constipation in Parkinson’s disease patients. Minerva Gastroenterol. Dietol. 2011, 57, 117–121.

- Georgescu, D.; Ancusa, O.E.; Georgescu, L.A.; Ionita, I.; Reisz, D. Nonmotor gastrointestinal disorders in older patients with Parkinson’s disease: Is there hope? Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1601–1608.

- La Fata, G.; Weber, P.; Mohajeri, M.H. Probiotics and the Gut Immune System: Indirect Regulation. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2018, 10, 11–21.

- Suez, J.; Zmora, N.; Segal, E.; Elinav, E. The pros, cons, and many unknowns of probiotics. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 716–729.

- Baldini, F.; Hertel, J.; Sandt, E.; Thinnes, C.C.; Neuberger-Castillo, L.; Pavelka, L.; Betsou, F.; Krüger, R.; Thiele, I. Parkinson’s disease-associated alterations of the gut microbiome predict disease-relevant changes in metabolic functions. BMC Biol. 2020, 18, 62.

- Bortolanza, M.; Nascimento, G.C.; Socias, S.B.; Ploper, D.; Chehín, R.N.; Raisman-Vozari, R.; Del-Bel, E. Tetracycline repurposing in neurodegeneration: Focus on Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2018, 125, 1403–1415.

- Pradhan, S.; Madke, B.; Kabra, P.; Singh, A. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of antibiotics and their use in dermatology. Indian J. Dermatol. 2016, 61, 469.

- Stoilova, T.; Colombo, L.; Forloni, G.; Tagliavini, F.; Salmona, M. A new face for old antibiotics: Tetracyclines in treatment of amyloidoses. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 5987–6006.

- Socias, S.B.; González-Lizárraga, F.; Avila, C.L.; Vera, C.; Acuña, L.; Sepulveda-Diaz, J.E.; Del-Bel, E.; Raisman-Vozari, R.; Chehin, R.N. Exploiting the therapeutic potential of ready-to-use drugs: Repurposing antibiotics against amyloid aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases. Prog. Neurobiol. 2018, 162, 17–36.

- Reglodi, D.; Renaud, J.; Tamas, A.; Tizabi, Y.; Socías, S.B.; Del-Bel, E.; Raisman-Vozari, R. Novel tactics for neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease: Role of antibiotics, polyphenols and neuropeptides. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 155, 120–148.

- Xu, L.; Surathu, A.; Raplee, I.; Chockalingam, A.; Stewart, S.; Walker, L.; Sacks, L.; Patel, V.; Li, Z.; Rouse, R. The effect of antibiotics on the gut microbiome: A metagenomics analysis of microbial shift and gut antibiotic resistance in antibiotic treated mice. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 263.

- Modi, S.R.; Collins, J.J.; Relman, D.A. Antibiotics and the gut microbiota. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 4212–4218.

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document: The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514.

- Derwa, Y.; Gracie, D.J.; Hamlin, P.J.; Ford, A.C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The efficacy of probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 389–400.

- Mazurak, N.; Broelz, E.; Storr, M.; Enck, P. Probiotic therapy of the irritable bowel syndrome: Why is the evidence still poor and what can be done about it? J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2015, 21, 471–485.

- Harper, A.; Naghibi, M.M.; Garcha, D. The role of bacteria, probiotics and diet in irritable bowel syndrome. Foods 2018, 7, 13.

- Wallace, C.J.K.; Milev, R. The effects of probiotics on depressive symptoms in humans: A systematic review. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2017, 16, 14.

- Wang, H.; Lee, I.S.; Braun, C.; Enck, P. Effect of probiotics on central nervous system functions in animals and humans: A systematic review. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 22, 589–605.

- Abildgaard, A.; Elfving, B.; Hokland, M.; Wegener, G.; Lund, S. Probiotic treatment reduces depressive-like behaviour in rats independently of diet. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 79, 40–48.

- Gazerani, P. Probiotics for Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4121.

- Gibson, G.R.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary Modulation of the Human Colonic Microbiota: Introducing the Concept of Prebiotics. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 1401–1412.

- De Vrese, M.; Schrezenmeir, J. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2008, 111, 1–66.

- Markowiak, P.; Ślizewska, K. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on human health. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1021.

- Cansev, M.; Ulus, I.H. Oral Administration of Phosphatide Precursors Enhances Learning and Memory by Promoting Synaptogenesis. In Handbook of Behavior, Food and Nutrition; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 489–504.

- Perez-Pardo, P.; de Jong, E.M.; Broersen, L.M.; van Wijk, N.; Attali, A.; Garssen, J.; Kraneveld, A.D. Promising Effects of Neurorestorative Diets on Motor, Cognitive, and Gastrointestinal Dysfunction after Symptom Development in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 57.

- Perez-Pardo, P.; Kliest, T.; Dodiya, H.B.; Broersen, L.M.; Garssen, J.; Keshavarzian, A.; Kraneveld, A.D. The gut-brain axis in Parkinson’s disease: Possibilities for food-based therapies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 817, 86–95.

- Makki, K.; Deehan, E.C.; Walter, J.; Bäckhed, F. The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 705–715.

- Statovci, D.; Aguilera, M.; MacSharry, J.; Melgar, S. The impact of western diet and nutrients on the microbiota and immune response at mucosal interfaces. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 838.

- Huang, B.; Liu, J.; Meng, T.; Li, Y.; He, D.; Ran, X.; Chen, G.; Guo, W.; Kan, X.; Fu, S.; et al. Polydatin Prevents Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Induced Parkinson’s Disease via Regulation of the AKT/GSK3β-Nrf2/NF-κB Signaling Axis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2527.

- Dutta, G.; Zhang, P.; Liu, B. The lipopolysaccharide Parkinson’s disease animal model: Mechanistic studies and drug discovery. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 22, 453–464.

- Jackson, A.; Forsyth, C.B.; Shaikh, M.; Voigt, R.M.; Engen, P.A.; Ramirez, V.; Keshavarzian, A. Diet in Parkinson’s Disease: Critical Role for the Microbiome. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1245.

- Dyall, S.C. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and the brain: A review of the independent and shared effects of EPA, DPA and DHA. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 52.

- Lombardi, V.C.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Subramanian, K.; Nourani, S.M.; Dagda, R.K.; Delaney, S.L.; Palotás, A. Nutritional modulation of the intestinal microbiota: Future opportunities for the prevention and treatment of neuroimmune and neuroinflammatory disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 61, 1–16.

- Ciulla, M.; Marinelli, L.; Cacciatore, I.; Di Stefano, A. Role of dietary supplements in the management of parkinson’s disease. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 271.

- Lange, K.W.; Nakamura, Y.; Chen, N.; Guo, J.; Kanaya, S.; Lange, K.M.; Li, S. Diet and medical foods in Parkinson’s disease. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2019, 8, 83–95.

- Kim, K.O.; Gluck, M. Fecal microbiota transplantation: An update on clinical practice. Clin. Endosc. 2019, 52, 137–143.

- Drekonja, D.; Reich, J.; Gezahegn, S.; Greer, N.; Shaukat, A.; MacDonald, R.; Rutks, I.; Wilt, T.J. Fecal microbiota transplantation for clostridium difficile infection a systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 630–638.

- Liubakka, A.; Vaughn, B.P. Clostridium difficile infection and fecal microbiota transplant. AACN Adv. Crit. Care 2016, 27, 324–337.

- Paramsothy, S.; Paramsothy, R.; Rubin, D.T.; Kamm, M.A.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Mitchell, H.M.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N. Faecal microbiota transplantation for inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2017, 11, 1180–1199.

- Kang, D.W.; Adams, J.B.; Coleman, D.M.; Pollard, E.L.; Maldonado, J.; McDonough-Means, S.; Caporaso, J.G.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Long-term benefit of Microbiota Transfer Therapy on autism symptoms and gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–9.

- Borody, T.; Leis, S.; Campbell, J.; Torres, M.; Nowak, A. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) in Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 352.

- Borody, T.J.; Nowak, A.; Finlayson, S. The GI microbiome and its role in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A summary of bacteriotherapy. J. Australas. College Nutr. Environ. Med. 2010, 31, 3.

- Li, N.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, A.; Lin, Y.; Jin, Y.; Li, X. Fecal microbiota transplantation from chronic unpredictable mild stress mice donors affects anxiety-like and depression-like behavior in recipient mice via the gut microbiota-inflammation-brain axis. Stress 2019, 22, 592–602.

- Kelly, J.R.; Borre, Y.; O’ Brien, C.; Patterson, E.; El Aidy, S.; Deane, J.; Kennedy, P.J.; Beers, S.; Scott, K.; Moloney, G.; et al. Transferring the blues: Depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 82, 109–118.

- Ainsworth, C. Therapeutic microbes to tackle disease. Nature 2020, 577, S20–S22.

- Early Clinical Trials With Live Biotherapeutic Products: Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Control Information; Guidance for Industry | FDA. Available online: (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Sandhu, K.; Peterson, V.; Dinan, T.G. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 179–194.

- Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 701–712.

- Kim, N.; Yun, M.; Oh, Y.J.; Choi, H.J. Mind-altering with the gut: Modulation of the gut-brain axis with probiotics. J. Microbiol. 2018, 56, 172–182.

- Morais, L.H.; Schreiber, H.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. The gut microbiota–brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 1–15.

- Libbrecht, M.W.; Noble, W.S. Machine learning applications in genetics and genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 321–332.

- Pietrucci, D.; Teofani, A.; Unida, V.; Cerroni, R.; Biocca, S.; Stefani, A.; Desideri, A. Can Gut Microbiota Be a Good Predictor for Parkinson’s Disease? A Machine Learning Approach. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 242.