A thrombus in a coronary artery causes ischemia, which eventually leads to myocardial infarction (MI) if not removed. However, removal generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), which causes ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury that damages the tissue and exacerbates the resulting MI. The mechanism of I/R injury is currently extensively understood. However, supplementation of exogenous antioxidants is ineffective against oxidative stress (OS). Enhancing the ability of endogenous antioxidants may be a more effective way to treat OS, and exosomes may play a role as targeted carriers. Exosomes are nanosized vesicles wrapped in biofilms which contain various complex RNAs and proteins. They are important intermediate carriers of intercellular communication and material exchange.

- exosome

- oxidative stress

- exosome therapy

- myocardial infarction

- coronary heart disease

- reactive oxygen radicals

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been the leading cause of mortality in recent years, and its incidence and mortality are closely related to coronary heart disease (CHD). CHD could cause a huge economic burden to regional or national medical systems [1,2][1][2]. CHD is, in fact, an inflammatory disease. Oxidative stress (OS) plays an important role in the development of coronary artery disease, and it is mainly caused by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and endogenous antioxidant defense system. At low levels, ROS causes subtle changes in intracellular pathways, such as redox signal transduction, but at higher levels it causes cell dysfunction and damage [3,4,5][3][4][5]. In the current research on exogenous anti-OS, the effects of OS damage were mot significantly reduced [6,7][6][7]. At present, strategies for the clinical treatment and prevention of atherosclerotic CVD still focus on the pharmacotherapy of arachidonic acid metabolism and antiplatelet aggregation (platelet P2Y12 inhibitors), as well as the treatment of related risk factors, such as high blood pressure, excessive lipids, and high blood sugar [8,9,10,11,12,13][8][9][10][11][12][13].

Exosomes are small vesicles [14,15,16][14][15][16] that contain complex RNAs and proteins which are found in natural body fluids, including blood, saliva, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, and milk [17,18][17][18]. Discovered in 1946, exosomes were first considered as “clotting factors” [19] that improved coagulation. After 20 years, electron microscopy revealed that platelet products contain vesicles measuring 20–50 nm [20]. Until 1987, Johnstone named these vesicles as “exosomes” [21]. Exosomes can be used as carriers for intercellular communication and can regulate protein expression in receptor cells by RNA transfer [22]. Intercellular communication is necessary in maintaining tissue/organ integrity/homeostasis and inducing adaptive changes to exogenous stimuli. In response to environmental damage and pathological conditions, many cell types release various exosomes of different quality and quantity into the circulation [23,24][23][24]. During OS, the exosomes released by cells can mediate signal transduction, change the defense mechanism of receptor cells, and enhance their resistance to OS [23]. In recent years, considerable attention was paid to the important role of exosomes in CVDs, such as ischemic heart disease [25,26,27,28,29][25][26][27][28][29].

Exosomes are released from damaged or diseased hearts, playing an important role in disease progression [30,31,32,33][30][31][32][33]. Considering the related experiments and clinical cell therapy studies, the important roles of exosomes in myocardial injury, repair, and regeneration are being increasingly recognized. According to some studies, the Framingham risk score used to predict CVD risk correlates with circulating exosomes [34,35][34][35]. Therefore, exosomes in the circulatory system are potential biomarkers of CVD. The selective packaging of miRNAs in exosomes and their functional transfer through specific signaling molecules are also important for disease treatment [36,37][36][37]. In addition, exosomes help detect the endogenous processes of myocardial recovery, regeneration, and protection [38]. They reflect the real-time microenvironment of the lesion, indicating that they are excellent biomarkers in clinical diagnosis. Exosomes are extremely useful because they can determine the pathophysiology of heart disease noninvasively.

In ischemic myocardium, especially after reperfusion, numerous ROS are produced [39,40][39][40]. ROS directly damage tissues, inducing cell death. In transgenic mice, infarct size was found to be significantly reduced when the antioxidant protein superoxide dismutase (SOD) was overexpressed [41,42][41][42]. Increasing the level of endogenous antioxidants can prevent reperfusion injury [43,44][43][44]. Exosomes can provide precise treatment through miRNAs by selecting the corresponding target cells and manipulating the corresponding components; thus, exosomes are a powerful tool for individualized therapy and gene therapy [45,46,47][45][46][47]. Therefore, the upregulation of endogenous antioxidants through exosomes seems to have good prospects.

2. Exosome-Regulated OS Responses after Myocardial Ischemia

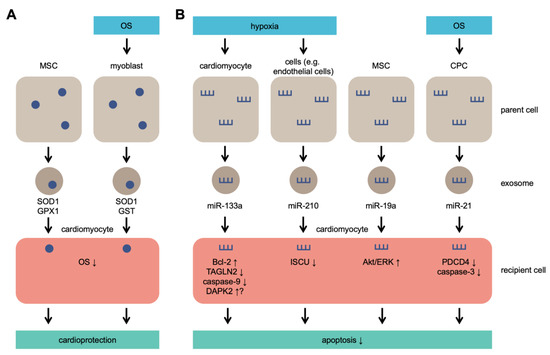

Although initially identified as cell debris, exosomes have many functions regulated by multiple signaling pathways. Exosomes are widely involved in the regulation of OS [48,49][48][49] and pathophysiological regulation of various cells; cellular pathophysiological processes include signal transduction, antigen presentation, and immune response [50,51][50][51]. Many of the previously conducted studies attempted to provide a detailed summary of the biogenesis of exosomes [52,53,54][52][53][54]. Figure 1 provides an illustration of exosome secretion under OS.

Exosome secretion under OS. Parent cells secrete exosomes containing antioxidant molecules that lead to cardioprotection (

) and/or microRNAs (miRs) that lead to inhibition of apoptosis (

). MSCs secrete SOD1, GPX1, and miR-19a without OS or hypoxia and protect cardiomyocytes exposed to OS. MSC: mesenchymal stem cells; CPC: cardiac progenitor cell; SOD1: superoxide dismutase 1; GPX1: glutathione peroxidase 1; GST: glutathione S-transferase; TAGLN2: transgelin 2; DAPK2: death-associated protein kinase 2; ISCU: iron–sulfur cluster assembly enzyme; PDCD4: programmed cell death 4.

In recent years, many studies concerning CVD highlighted that exosomes not only transport proteins, RNA, DNA, and other molecules under physiological conditions but also participate in pathological conditions such as ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury, atherosclerosis, and cardiac remodeling [55,56,57,58,59,60,61][55][56][57][58][59][60][61]. They can modify gene expression and protein synthesis by inhibiting protein synthesis or initiating mRNA degradation to perform their functions at the post-transcriptional level. Moreover, circulating exosomes are considered as new biomarkers of disease performance and progression [57,62,63][57][62][63].

Under pathological conditions, the exosomes released during OS carry antioxidant molecules, such as superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) and glutathione S-transferase (GST) [62[62][63],63], and defense molecules, such as glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1) [64], which can be absorbed by neighboring cells to enrich their cellular defense mechanisms; thus, these cells are already protected from OS induced by adverse environmental conditions. Therefore, exosomes can potentially transfer defense molecules from one cell to another [65]. For example, in vitro, serum exosomes from healthy human volunteers attenuated H2O2-induced H9c2 cell apoptosis via ERK1/2 signaling pathway activation [66]. Moreover, cardiomyocytes (CMs) secrete miR-30a–rich exosomes after hypoxia stimulation [67]. When the release of miR-30a from exosomes is inhibited, autophagy and OS response in CMs may be maintained after hypoxia [68].

Furthermore, rapid ROS increase and OS occurrence are related to antioxidant depletion. Supplementation of related exogenous antioxidants, such as vitamin E and folic acid, might achieve good effects against OS [69,70][69][70]. However, a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials involving 294,478 participants indicated that supplementation of exogenous vitamins and antioxidants was not associated with a reduction in the risk of major CVDs [71]. Interestingly, supplementation with N-acetylcysteine to increase endogenous antioxidants (e.g., glutathione (GSH)) can achieve good antioxidant capacity. After being absorbed by cells, N-acetylcysteine is transformed into cysteine. When the cysteine level increases, the synthesis rate of GSH also increases. More importantly, N-acetylcysteine supplementation not only improves the prognosis of patients but also produces no adverse side effects [72,73,74,75][72][73][74][75]. Increasing the ratio of GSH/oxidized GSH (GSSG) in patients with heart failure and acute myocardial infarction (MI) can reduce OS and improve the MI area and cardiac function [72,73,74,75][72][73][74][75]. This finding is also beneficial for the treatment of exosomes, considering that endogenous antioxidants, such as catalase, can be delivered directly through exosomes [76]. Catalase is the main enzyme that regulates H2O2 metabolism. The level of catalase gradually decreases over time after MI [77]. Its overexpression can reduce myocardial I/R injury [78]. After reformation and reshaping of exosomes by sonication and extrusion procedures, catalase could be loaded into exosomes, with a loading capacity of 20–26% [79]. In addition, catalase exosomes can be obtained by modifying parent cells (monocytes/macrophages) and then isolating from the conditioned medium [80].

As natural drug delivery nanoparticles, exosomes have the advantages of cell-based drug delivery and nanoscale size, which aid in achieving effective drug delivery. Exosomes are also lipid vesicles and ideal carriers [81]. In recent years, the application of exosomes as a biomaterial for drug delivery has improved rapidly. At present, treatment with autologous exosomes can help obtain long-term and stable activation of immune effectors [82]. Furthermore, certain drugs can modify exosomes to form carriers with different properties. In mice, the introduction of polyethylene glycol to the exosome surface significantly increased the circulation time of exosomes [83]. However, systemic delivery of exosomes appears to accumulate in the spleen and liver [84,85,86][84][85][86]. To solve this issue, we need to modify the exosomes to increase their targeting to specific tissues or cells. Cells that produce exosomes should be engineered to drive the expression of targeting moieties fused with exosomal membrane proteins. For example, Alvarez-Erviti et al. [87] modified dendritic cells to express Lamp2b, an exosomal membrane protein fused to neuron-specific rabies viral glycoprotein (RVG) peptide, to obtain exosomal targeting. In addition, Wiklander et al. [88] found that compared with unmodified exosomes, RVG-targeted exosomes greatly accumulate in the brain after systemic administration. At the same time, the ability of exosomes to target hypoxic cells in vivo can be enhanced by combining exosomes with hypoxia-targeting peptides or antibodies through bioengineering technology [89,90][89][90]. Moreover, exosomes released by different cells, such as immune cells, may be more effective in targeting hypoxic tissue in vivo [91]. An alternative strategy for the noninvasive targeting of magnetic drugs (i.e., enhancing drug delivery to selected tissues by applying a magnetic field gradient) was also proposed decades ago [92,93][92][93]. In this strategy, the therapeutic agent and iron oxide nanoparticles together with macrophages are incubated, leading to the production of exosomes loaded with both the therapeutic and magnetic nanoparticles. However, this method may have the disadvantages of toxicity and difficulty in targeting deep tissues. Moreover, exosomes can be used for different ways, such as intraperitoneal injection, subcutaneous injection, and nasal administration. Different administration routes may help improve the therapeutic effect [94]. For example, the intranasal administration of catalase-loaded exosomes in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease resulted in the increased accumulation of exosomes in brain tissue after four hours [76].

Exosomes as carriers can prevent internal molecular degradation and target special tissues, thereby improving bioavailability and reducing side effects. Moreover, exosomes can serve as carriers for drug delivery and have the potential to easily manipulate the expression of RNA and proteins [87]. Exosomes naturally occur and possess adhesion proteins, which can bind to target cells and remain in target tissues during transplantation [95]. In addition, exosomes have long-term preservation and no degradation because of the existence of resistant membranes. The membrane of exosomes may pass through the blood–brain barrier [96].

Exosomes have great advantages as carriers; however, “nonvesicles,” which are distinct particles that have low electron density without restrictive membranes, are present in exosome preparation [97]. Nonetheless, the appearance of artificial nanovesicles (exosome-mimetic nanovesicles) [91,98][91][98] may be helpful in solving this issue.

3. Several Possible Exosomal miRNA Loads

Exosomes contain various molecules, including proteins, lipids, DNA, mRNA, and miRNA, and relevant data can be acquired from the ExoCarta database [99]. Considering the various regulatory roles of miRNA in gene expression, more attention was paid to miRNA. The proportion of miRNA in exosomes is higher than that in their parent cells [100], and miRNA can be transferred between cells through exosomes [22,36][22][36]. Meanwhile, miRNAs in exosomes are protected by vesicles and can be stably maintained in circulation; eventually, they are transferred to target cells to inhibit the expression of some genes [101,102][101][102]. For example, the knockdown of beta-secretase 1 (BACE1) mRNA and protein was detected in mouse brains after tail vein injection of siRNA-containing exosomes [87]. Therefore, miRNA seems to have a good potential as a content in exosomes.

4. Advantages of Exosome Therapy in CHD Compared with Those of Stem-Cell Therapy

Over the years, various strategies were tried to find a more effective treatment after CVD occurrence. Currently, stem-cell therapy is an attractive method for CHD prevention and treatment [143,144,145][103][104][105]. In 1993, Koh et al. [146][106] proved that skeletal muscle myoblasts can be stably transplanted into CMs, demonstrating long-term survival, proliferation, and differentiation. Recently, research focus shifted to bone marrow-derived MSCs [147][107], and the relevant experiments achieved favorable results [148,149,150][108][109][110]. Previously, differentiation characteristics were the main mechanism for cell transplantation to exert therapeutic effects, however, stem cells did not necessarily differentiate into CMs or endothelial cells after transplantation into ischemic myocardium, but the antiapoptotic, antioxidant stress, and anti-inflammatory effects were mediated by exosomes, thereby improving cardiac function after ischemia [151][111]. Furthermore, stem-cell transplantation can lead to arrhythmia [152,153,154,155,156,157,158][112][113][114][115][116][117][118].

The secretory properties of cell transplantation represent an important scientific issue in CHD. Interestingly, exosomes produced during myocardial ischemia can mediate the preventive and therapeutic effects of cell transplantation [159][119]. Exosomes do have a protective effect on the cardiovascular system [26[26][120],160], which was first reported more than 10 years ago [161][121]. In porcine and mouse models of myocardial I/R injury, 100–200 nm macromolecular complexes secreted by stem cells protected cells under OS. In the subsequent biophysical studies, the biologically active component was characterized as an exosome. More direct evidence suggested that adult stem cells repair heart tissue by releasing paracrine and autocrine factors [162][122]. For instance, in the isolated Langendorff I/R injury model, purified exosomes derived from MSCs reduced MI in mice [62]. In further experiments, exosome therapy restored the energy consumption and OS levels of the mouse heart within 30 min after I/R and activated cardioprotective PI3K/Akt signaling [163][123]. Results of a meta-analysis confirmed these cardioprotective effects of MSC-derived exosomes in myocardial injury [164][124]. I/R results in consumption of intracellular ATP to a large extent, and exosomes from adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) were observed to supplement intracellular ATP, NADH, phosphorylated AKT, and phosphorylated GSK-3β levels, while reducing phosphorylated c-JNK and recovering cell bioenergy [165][125]. The exosomes from ADSCs also increase IL-6 expression and phosphorylate STAT3, which in turn activates the classical signaling pathway and accelerates recovery from injury and angiogenesis after I/R [166][126]. The effects of exosomes derived from stem cells due to reduction of myocardial OS damage are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Effect of exosomes derived from stem cells on the reduction of myocardial oxidative stress (OS) damage. ADSC: adipose-derived stem cell; CPC: cardiac progenitor cell; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; ATG7: autophagy-related 7; TLR4: Toll-like receptor 4; PDCD4: programmed cell death 4.

Origin of Exosome | Mechanistic Detail of OS Damage Reduction | References | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ADSC | promotes neovascularization and alleviates inflammation and apoptosis |

[165] |

[125] |

|||||

upregulated miR-93-5p suppresses autophagy and inflammatory cytokine expression by targeting ATG7 and TLR4 |

[174] |

[127] |

||||||

CPC | upregulated miR-21 inhibits apoptosis by targeting PDCD4 |

[175] |

[128] |

|||||

inhibits caspase 3/7 activity |

[173] |

[129] |

||||||

activates ERK1/2 pathway and inhibits apoptosis |

[66] |

|||||||

MSC | increases ATP level and activates PI3K/Akt pathway |

[163] |

[123] |

|||||

activates Akt/Sfrp2 pathway |

[176] |

[130] |

||||||

upregulated miR-19a activates Akt/ERK pathway |

[109] |

[131] |

References

- Hao, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, N.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; Huo, Y.; Fonarow, G.C.; Ge, J.; Taubert, K.A.; Morgan, L.; et al. Sex differences in in-hospital management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation 2019, 139, 1776–1785.

- Benjamin, E.J.; Muntner, P.; Alonso, A.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Das, S.R.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation 2019, 139, e56–e528.

- Li, R.; Jia, Z.; Trush, M.A. Defining ros in biology and medicine. React. Oxyg. Species 2016, 1, 9–21.

- Angelova, P.R.; Abramov, A.Y. Role of mitochondrial ros in the brain: From physiology to neurodegeneration. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 692–702.

- Yang, S.; Lian, G. Ros and diseases: Role in metabolism and energy supply. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2020, 467, 1–12.

- Lonn, E.; Bosch, J.; Yusuf, S.; Sheridan, P.; Pogue, J.; Arnold, J.M.; Ross, C.; Arnold, A.; Sleight, P.; Probstfield, J.; et al. Effects of long-term vitamin e supplementation on cardiovascular events and cancer: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005, 293, 1338–1347.

- van der Pol, A.; van Gilst, W.H.; Voors, A.A.; van der Meer, P. Treating oxidative stress in heart failure: Past, present and future. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 425–435.

- Weitz, J. Hemostasis, thrombosis, fibrinolysis and cardiovascular disease. In Braunwald’s Heart Disease; Mann, Z., Ed.; Elsevier/Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 1809–1833.

- Jellinger, P.S.; Handelsman, Y.; Rosenblit, P.D.; Bloomgarden, Z.T.; Fonseca, V.A.; Garber, A.J.; Grunberger, G.; Guerin, C.K.; Bell, D.S.H.; Mechanick, J.I.; et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists and american college of endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr. Pract. 2017, 23, 1–87.

- Kinoshita, M.; Yokote, K.; Arai, H.; Iida, M.; Ishigaki, Y.; Ishibashi, S.; Umemoto, S.; Egusa, G.; Ohmura, H.; Okamura, T.; et al. Japan atherosclerosis society (jas) guidelines for prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases 2017. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2018, 25, 846–984.

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; de Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 aha/acc/aacvpr/aapa/abc/acpm/ada/ags/apha/aspc/nla/pcna guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2019, 73, e285–e350.

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 acc/aha/aapa/abc/acpm/ags/apha/ash/aspc/nma/pcna guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive summary: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2018, 138, e426–e483.

- Ferdinandy, P.; Hausenloy, D.J.; Heusch, G.; Baxter, G.F.; Schulz, R. Interaction of risk factors, comorbidities, and comedications with ischemia/reperfusion injury and cardioprotection by preconditioning, postconditioning, and remote conditioning. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 1142–1174.

- Raposo, G.; Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 373–383.

- Alenquer, M.; Amorim, M.J. Exosome biogenesis, regulation, and function in viral infection. Viruses 2015, 7, 5066–5083.

- Doyle, L.M.; Wang, M.Z. Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells 2019, 8, 727.

- Thery, C.; Ostrowski, M.; Segura, E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 581–593.

- van der Pol, E.; Boing, A.N.; Harrison, P.; Sturk, A.; Nieuwland, R. Classification, functions, and clinical relevance of extracellular vesicles. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64, 676–705.

- Chargaff, E.; West, R. The biological significance of the thromboplastic protein of blood. J. Biol. Chem. 1946, 166, 189–197.

- Wolf, P. The nature and significance of platelet products in human plasma. Br. J. Haematol. 1967, 13, 269–288.

- Johnstone, R.M.; Adam, M.; Hammond, J.R.; Orr, L.; Turbide, C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes). J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 9412–9420.

- Valadi, H.; Ekstrom, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjostrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lotvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mrnas and micrornas is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659.

- Eldh, M.; Ekstrom, K.; Valadi, H.; Sjostrand, M.; Olsson, B.; Jernas, M.; Lotvall, J. Exosomes communicate protective messages during oxidative stress; possible role of exosomal shuttle rna. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15353.

- Yuan, M.J.; Maghsoudi, T.; Wang, T. Exosomes mediate the intercellular communication after myocardial infarction. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 13, 113–116.

- Sluijter, J.P.; Verhage, V.; Deddens, J.C.; van den Akker, F.; Doevendans, P.A. Microvesicles and exosomes for intracardiac communication. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 102, 302–311.

- Davidson, S.M.; Takov, K.; Yellon, D.M. Exosomes and cardiovascular protection. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2017, 31, 77–86.

- Lawson, C.; Vicencio, J.M.; Yellon, D.M.; Davidson, S.M. Microvesicles and exosomes: New players in metabolic and cardiovascular disease. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 228, R57–R71.

- Barile, L.; Moccetti, T.; Marban, E.; Vassalli, G. Roles of exosomes in cardioprotection. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1372–1379.

- Ibrahim, A.; Marban, E. Exosomes: Fundamental biology and roles in cardiovascular physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2016, 78, 67–83.

- Khan, M.; Nickoloff, E.; Abramova, T.; Johnson, J.; Verma, S.K.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Mackie, A.R.; Vaughan, E.; Garikipati, V.N.; Benedict, C.; et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived exosomes promote endogenous repair mechanisms and enhance cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 2015, 117, 52–64.

- Xie, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Du, H.; Sun, C.; Shao, X.; Tian, J.; Gu, X.; Wang, H.; Tian, J.; et al. Adipose-derived exosomes exert proatherogenic effects by regulating macrophage foam cell formation and polarization. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e007442.

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, W.; Xie, L.; Zhao, Z.A.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Lei, W.; Shen, Z. Microrna-133 overexpression promotes the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells on acute myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 268.

- Komaki, M.; Numata, Y.; Morioka, C.; Honda, I.; Tooi, M.; Yokoyama, N.; Ayame, H.; Iwasaki, K.; Taki, A.; Oshima, N.; et al. Exosomes of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells stimulate angiogenesis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 219.

- Nozaki, T.; Sugiyama, S.; Koga, H.; Sugamura, K.; Ohba, K.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Sumida, H.; Matsui, K.; Jinnouchi, H.; Ogawa, H. Significance of a multiple biomarkers strategy including endothelial dysfunction to improve risk stratification for cardiovascular events in patients at high risk for coronary heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 601–608.

- Amabile, N.; Cheng, S.; Renard, J.M.; Larson, M.G.; Ghorbani, A.; McCabe, E.; Griffin, G.; Guerin, C.; Ho, J.E.; Shaw, S.Y.; et al. Association of circulating endothelial microparticles with cardiometabolic risk factors in the framingham heart study. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2972–2979.

- Montecalvo, A.; Larregina, A.T.; Shufesky, W.J.; Stolz, D.B.; Sullivan, M.L.; Karlsson, J.M.; Baty, C.J.; Gibson, G.A.; Erdos, G.; Wang, Z.; et al. Mechanism of transfer of functional micrornas between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood 2012, 119, 756–766.

- Stoorvogel, W. Functional transfer of microrna by exosomes. Blood 2012, 119, 646–648.

- Sahoo, S.; Losordo, D.W. Exosomes and cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 333–344.

- Kukielka, G.L.; Smith, C.W.; Manning, A.M.; Youker, K.A.; Michael, L.H.; Entman, M.L. Induction of interleukin-6 synthesis in the myocardium. Potential role in postreperfusion inflammatory injury. Circulation 1995, 92, 1866–1875.

- von Knethen, A.; Callsen, D.; Brune, B. Superoxide attenuates macrophage apoptosis by nf-kappa b and ap-1 activation that promotes cyclooxygenase-2 expression. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 2858–2866.

- Chen, Z.; Siu, B.; Ho, Y.S.; Vincent, R.; Chua, C.C.; Hamdy, R.C.; Chua, B.H. Overexpression of mnsod protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in transgenic mice. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998, 30, 2281–2289.

- Wang, P.; Chen, H.; Qin, H.; Sankarapandi, S.; Becher, M.W.; Wong, P.C.; Zweier, J.L. Overexpression of human copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase (sod1) prevents postischemic injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 4556–4560.

- Suzuki, K.; Murtuza, B.; Sammut, I.A.; Latif, N.; Jayakumar, J.; Smolenski, R.T.; Kaneda, Y.; Sawa, Y.; Matsuda, H.; Yacoub, M.H. Heat shock protein 72 enhances manganese superoxide dismutase activity during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, associated with mitochondrial protection and apoptosis reduction. Circulation 2002, 106, I270–I276.

- Peng, X.; Li, Y. Induction of cellular glutathione-linked enzymes and catalase by the unique chemoprotective agent, 3h-1,2-dithiole-3-thione in rat cardiomyocytes affords protection against oxidative cell injury. Pharmacol. Res. 2002, 45, 491–497.

- Nouraee, N.; Mowla, S.J. Mirna therapeutics in cardiovascular diseases: Promises and problems. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 232.

- O’Loughlin, A.J.; Woffindale, C.A.; Wood, M.J. Exosomes and the emerging field of exosome-based gene therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2012, 12, 262–274.

- Houseley, J.; LaCava, J.; Tollervey, D. Rna-quality control by the exosome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 529–539.

- Wang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, M.; Yan, M.; Jiang, J.; Li, Z. Exosomes derived mir-126 attenuates oxidative stress and apoptosis from ischemia and reperfusion injury by targeting errfi1. Gene 2019, 690, 75–80.

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, W.; Zhao, B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Bihl, J.C. Ace2-epc-exs protect ageing ecs against hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury through the mir-18a/nox2/ros pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 1873–1882.

- Zhang, B.; Yin, Y.; Lai, R.C.; Tan, S.S.; Choo, A.B.; Lim, S.K. Mesenchymal stem cells secrete immunologically active exosomes. Stem Cells Dev. 2014, 23, 1233–1244.

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, H.; Xu, W.; Wang, B.; Wu, H.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, M.; Mao, F.; Yan, Y.; et al. Exosomes released by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells protect against cisplatin-induced renal oxidative stress and apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013, 4, 34.

- Pollet, H.; Conrard, L.; Cloos, A.S.; Tyteca, D. Plasma membrane lipid domains as platforms for vesicle biogenesis and shedding? Biomolecules 2018, 8, 94.

- Gola, A.; Niewolna, M.; Werynska, B. Results of the combined treatment of advanced multiple myeloma by the m-2 protocol: Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, melphalan, nitrosourea and prednisone. Pol. Arch. Med. 1987, 77, 200–205.

- Kang, X.; Zuo, Z.; Hong, W.; Tang, H.; Geng, W. Progress of research on exosomes in the protection against ischemic brain injury. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1149.

- Poe, A.J.; Knowlton, A.A. Exosomes as agents of change in the cardiovascular system. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2017, 111, 40–50.

- Shanmuganathan, M.; Vughs, J.; Noseda, M.; Emanueli, C. Exosomes: Basic biology and technological advancements suggesting their potential as ischemic heart disease therapeutics. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1159.

- Jansen, F.; Nickenig, G.; Werner, N. Extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular disease: Potential applications in diagnosis, prognosis, and epidemiology. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1649–1657.

- Bellin, G.; Gardin, C.; Ferroni, L.; Chachques, J.C.; Rogante, M.; Mitrecic, D.; Ferrari, R.; Zavan, B. Exosome in cardiovascular diseases: A complex world full of hope. Cells 2019, 8, 166.

- Shah, R.; Patel, T.; Freedman, J.E. Circulating extracellular vesicles in human disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 958–966.

- Hafiane, A.; Daskalopoulou, S.S. Extracellular vesicles characteristics and emerging roles in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Metabolism 2018, 85, 213–222.

- Osteikoetxea, X.; Nemeth, A.; Sodar, B.W.; Vukman, K.V.; Buzas, E.I. Extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular disease: Are they jedi or sith? J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 2881–2894.

- Lai, R.C.; Arslan, F.; Lee, M.M.; Sze, N.S.; Choo, A.; Chen, T.S.; Salto-Tellez, M.; Timmers, L.; Lee, C.N.; El Oakley, R.M.; et al. Exosome secreted by msc reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2010, 4, 214–222.

- Fahs, A.; Ramadan, F.; Ghamloush, F.; Ayoub, A.J.; Ahmad, F.A.; Kobeissy, F.; Mechref, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, R.; Hussein, N.; et al. Effects of the oncoprotein pax3-foxo1 on modulation of exosomes function and protein content: Implications on oxidative stress protection and enhanced plasticity. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1784.

- Yan, Y.; Jiang, W.; Tan, Y.; Zou, S.; Zhang, H.; Mao, F.; Gong, A.; Qian, H.; Xu, W. Hucmsc exosome-derived gpx1 is required for the recovery of hepatic oxidant injury. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 465–479.

- Saeed-Zidane, M.; Linden, L.; Salilew-Wondim, D.; Held, E.; Neuhoff, C.; Tholen, E.; Hoelker, M.; Schellander, K.; Tesfaye, D. Cellular and exosome mediated molecular defense mechanism in bovine granulosa cells exposed to oxidative stress. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187569.

- Li, P.; Liu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Gu, H.; Dai, Q.; Yao, J.; Zhou, L. Serum exosomes attenuate h2o2-induced apoptosis in rat h9c2 cardiomyocytes via erk1/2. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2019, 12, 37–44.

- Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Cheng, X.; Liao, Y.; Yu, X. Exosomal transfer of mir-30a between cardiomyocytes regulates autophagy after hypoxia. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 94, 711–724.

- Xu, Y.Q.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.H. Effect of exosome-carried mir-30a on myocardial apoptosis in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury rats through regulating autophagy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 7066–7072.

- Hamblin, M.; Smith, H.M.; Hill, M.F. Dietary supplementation with vitamin e ameliorates cardiac failure in type i diabetic cardiomyopathy by suppressing myocardial generation of 8-iso-prostaglandin f2alpha and oxidized glutathione. J. Card. Fail. 2007, 13, 884–892.

- Li, W.; Tang, R.; Ouyang, S.; Ma, F.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. Folic acid prevents cardiac dysfunction and reduces myocardial fibrosis in a mouse model of high-fat diet-induced obesity. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 14, 68.

- Myung, S.K.; Ju, W.; Cho, B.; Oh, S.W.; Park, S.M.; Koo, B.K.; Park, B.J.; Korean Meta-Analysis Study, G. Efficacy of vitamin and antioxidant supplements in prevention of cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2013, 346, f10.

- Sochman, J.; Vrbska, J.; Musilova, B.; Rocek, M. Infarct size limitation: Acute n-acetylcysteine defense (island trial): Preliminary analysis and report after the first 30 patients. Clin. Cardiol. 1996, 19, 94–100.

- Sochman, J.; Peregrin, J.H. Total recovery of left ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction: Comprehensive therapy with streptokinase, n-acetylcysteine and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Int. J. Cardiol. 1992, 35, 116–118.

- Arstall, M.A.; Yang, J.; Stafford, I.; Betts, W.H.; Horowitz, J.D. N-acetylcysteine in combination with nitroglycerin and streptokinase for the treatment of evolving acute myocardial infarction. Safety and biochemical effects. Circulation 1995, 92, 2855–2862.

- Mehra, A.; Shotan, A.; Ostrzega, E.; Hsueh, W.; Vasquez-Johnson, J.; Elkayam, U. Potentiation of isosorbide dinitrate effects with n-acetylcysteine in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 1994, 89, 2595–2600.

- Haney, M.J.; Klyachko, N.L.; Zhao, Y.; Gupta, R.; Plotnikova, E.G.; He, Z.; Patel, T.; Piroyan, A.; Sokolsky, M.; Kabanov, A.V.; et al. Exosomes as drug delivery vehicles for parkinson’s disease therapy. J. Control. Release 2015, 207, 18–30.

- Khaper, N.; Kaur, K.; Li, T.; Farahmand, F.; Singal, P.K. Antioxidant enzyme gene expression in congestive heart failure following myocardial infarction. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 251, 9–15.

- Li, G.; Chen, Y.; Saari, J.T.; Kang, Y.J. Catalase-overexpressing transgenic mouse heart is resistant to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 273, H1090–H1095.

- Batrakova, E.V.; Kim, M.S. Using exosomes, naturally-equipped nanocarriers, for drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2015, 219, 396–405.

- Zhao, Y.; Haney, M.J.; Gupta, R.; Bohnsack, J.P.; He, Z.; Kabanov, A.V.; Batrakova, E.V. Gdnf-transfected macrophages produce potent neuroprotective effects in parkinson’s disease mouse model. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106867.

- van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228.

- Escudier, B.; Dorval, T.; Chaput, N.; Andre, F.; Caby, M.P.; Novault, S.; Flament, C.; Leboulaire, C.; Borg, C.; Amigorena, S.; et al. Vaccination of metastatic melanoma patients with autologous dendritic cell (dc) derived-exosomes: Results of thefirst phase i clinical trial. J. Transl. Med. 2005, 3, 10.

- Kooijmans, S.A.A.; Fliervoet, L.A.L.; van der Meel, R.; Fens, M.; Heijnen, H.F.G.; van Bergen En Henegouwen, P.M.P.; Vader, P.; Schiffelers, R.M. Pegylated and targeted extracellular vesicles display enhanced cell specificity and circulation time. J. Control. Release 2016, 224, 77–85.

- Imai, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Nishikawa, M.; Kato, K.; Morishita, M.; Yamashita, T.; Matsumoto, A.; Charoenviriyakul, C.; Takakura, Y. Macrophage-dependent clearance of systemically administered b16bl6-derived exosomes from the blood circulation in mice. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 26238.

- Yanez-Mo, M.; Siljander, P.R.; Andreu, Z.; Zavec, A.B.; Borras, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066.

- Di Rocco, G.; Baldari, S.; Toietta, G. Towards therapeutic delivery of extracellular vesicles: Strategies for in vivo tracking and biodistribution analysis. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 5029619.

- Alvarez-Erviti, L.; Seow, Y.; Yin, H.; Betts, C.; Lakhal, S.; Wood, M.J. Delivery of sirna to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 341–345.

- Wiklander, O.P.; Nordin, J.Z.; O’Loughlin, A.; Gustafsson, Y.; Corso, G.; Mager, I.; Vader, P.; Lee, Y.; Sork, H.; Seow, Y.; et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 26316.

- Splith, K.; Bergmann, R.; Pietzsch, J.; Neundorf, I. Specific targeting of hypoxic tumor tissue with nitroimidazole-peptide conjugates. Chem. Med. Chem. 2012, 7, 57–61.

- Lee, K.Y.; Hopkins, J.D.; Syvanen, M. Direct involvement of is26 in an antibiotic resistance operon. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 3229–3236.

- Jang, S.C.; Kim, O.Y.; Yoon, C.M.; Choi, D.S.; Roh, T.Y.; Park, J.; Nilsson, J.; Lotvall, J.; Kim, Y.K.; Gho, Y.S. Bioinspired exosome-mimetic nanovesicles for targeted delivery of chemotherapeutics to malignant tumors. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 7698–7710.

- Widder, K.J.; Senyei, A.E.; Ranney, D.F. Magnetically responsive microspheres and other carriers for the biophysical targeting of antitumor agents. Adv. Pharmacol. Chemother. 1979, 16, 213–271.

- Senyei, A.E.; Reich, S.D.; Gonczy, C.; Widder, K.J. In vivo kinetics of magnetically targeted low-dose doxorubicin. J. Pharm. Sci. 1981, 70, 389–391.

- Vader, P.; Mol, E.A.; Pasterkamp, G.; Schiffelers, R.M. Extracellular vesicles for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 106, 148–156.

- Carrasco-Ramirez, P.; Greening, D.W.; Andres, G.; Gopal, S.K.; Martin-Villar, E.; Renart, J.; Simpson, R.J.; Quintanilla, M. Podoplanin is a component of extracellular vesicles that reprograms cell-derived exosomal proteins and modulates lymphatic vessel formation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 16070–16089.

- Zhuang, X.; Xiang, X.; Grizzle, W.; Sun, D.; Zhang, S.; Axtell, R.C.; Ju, S.; Mu, J.; Zhang, L.; Steinman, L.; et al. Treatment of brain inflammatory diseases by delivering exosome encapsulated anti-inflammatory drugs from the nasal region to the brain. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 1769–1779.

- Grigor’eva, A.E.; Dyrkheeva, N.S.; Bryzgunova, O.E.; Tamkovich, S.N.; Chelobanov, B.P.; Ryabchikova, E.I. Contamination of exosome preparations, isolated from biological fluids. Biomed. Khim. 2017, 63, 91–96.

- Lunavat, T.R.; Jang, S.C.; Nilsson, L.; Park, H.T.; Repiska, G.; Lasser, C.; Nilsson, J.A.; Gho, Y.S.; Lotvall, J. Rnai delivery by exosome-mimetic nanovesicles-Implications for targeting c-Myc in cancer. Biomaterials 2016, 102, 231–238.

- Simpson, R.J.; Kalra, H.; Mathivanan, S. Exocarta as a resource for exosomal research. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2012, 1, 1.

- Goldie, B.J.; Dun, M.D.; Lin, M.; Smith, N.D.; Verrills, N.M.; Dayas, C.V.; Cairns, M.J. Activity-associated mirna are packaged in map1b-enriched exosomes released from depolarized neurons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 9195–9208.

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Bian, Z.; Sun, F.; Lu, J.; Yin, Y.; Cai, X.; et al. Secreted monocytic mir-150 enhances targeted endothelial cell migration. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 133–144.

- de Jong, O.G.; Verhaar, M.C.; Chen, Y.; Vader, P.; Gremmels, H.; Posthuma, G.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Gucek, M.; van Balkom, B.W. Cellular stress conditions are reflected in the protein and rna content of endothelial cell-derived exosomes. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2012, 1, 1.

- Segers, V.F.; Lee, R.T. Stem-cell therapy for cardiac disease. Nature 2008, 451, 937–942.

- Michler, R.E. Stem cell therapy for heart failure. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc. J. 2013, 9, 187–194.

- Nagaya, N.; Kangawa, K.; Itoh, T.; Iwase, T.; Murakami, S.; Miyahara, Y.; Fujii, T.; Uematsu, M.; Ohgushi, H.; Yamagishi, M.; et al. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells improves cardiac function in a rat model of dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2005, 112, 1128–1135.

- Koh, G.Y.; Klug, M.G.; Soonpaa, M.H.; Field, L.J. Differentiation and long-term survival of c2c12 myoblast grafts in heart. J. Clin. Investig. 1993, 92, 1548–1554.

- Mendicino, M.; Bailey, A.M.; Wonnacott, K.; Puri, R.K.; Bauer, S.R. Msc-based product characterization for clinical trials: An fda perspective. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 141–145.

- Lalu, M.M.; Mazzarello, S.; Zlepnig, J.; Dong, Y.Y.R.; Montroy, J.; McIntyre, L.; Devereaux, P.J.; Stewart, D.J.; David Mazer, C.; Barron, C.C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of adult stem cell therapy for acute myocardial infarction and ischemic heart failure (safecell heart): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 857–866.

- Huang, P.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, G.; Qian, H.; Jin, C.; Yu, Y.; et al. Combinatorial treatment of acute myocardial infarction using stem cells and their derived exosomes resulted in improved heart performance. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 300.

- Kim, S.H.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, M.Y.; Lee, M.G.; Kang, W.Y.; Lee, K.S.; Ahn, Y.K.; et al. Improvement in left ventricular function with intracoronary mesenchymal stem cell therapy in a patient with anterior wall st-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2018, 32, 329–338.

- Ibrahim, A.G.; Cheng, K.; Marban, E. Exosomes as critical agents of cardiac regeneration triggered by cell therapy. Stem Cell Rep. 2014, 2, 606–619.

- Chong, J.J.; Yang, X.; Don, C.W.; Minami, E.; Liu, Y.W.; Weyers, J.J.; Mahoney, W.M.; Van Biber, B.; Cook, S.M.; Palpant, N.J.; et al. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature 2014, 510, 273–277.

- Hartman, M.E.; Dai, D.F.; Laflamme, M.A. Human pluripotent stem cells: Prospects and challenges as a source of cardiomyocytes for in vitro modeling and cell-based cardiac repair. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 96, 3–17.

- Zhang, Y.M.; Hartzell, C.; Narlow, M.; Dudley, S.C., Jr. Stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes demonstrate arrhythmic potential. Circulation 2002, 106, 1294–1299.

- Chen, H.S.; Kim, C.; Mercola, M. Electrophysiological challenges of cell-based myocardial repair. Circulation 2009, 120, 2496–2508.

- Menasche, P.; Hagege, A.A.; Vilquin, J.T.; Desnos, M.; Abergel, E.; Pouzet, B.; Bel, A.; Sarateanu, S.; Scorsin, M.; Schwartz, K.; et al. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for severe postinfarction left ventricular dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 1078–1083.

- Smits, P.C.; van Geuns, R.J.; Poldermans, D.; Bountioukos, M.; Onderwater, E.E.; Lee, C.H.; Maat, A.P.; Serruys, P.W. Catheter-based intramyocardial injection of autologous skeletal myoblasts as a primary treatment of ischemic heart failure: Clinical experience with six-month follow-up. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 42, 2063–2069.

- Dib, N.; McCarthy, P.; Campbell, A.; Yeager, M.; Pagani, F.D.; Wright, S.; MacLellan, W.R.; Fonarow, G.; Eisen, H.J.; Michler, R.E.; et al. Feasibility and safety of autologous myoblast transplantation in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. Cell Transplant. 2005, 14, 11–19.

- Giricz, Z.; Varga, Z.V.; Baranyai, T.; Sipos, P.; Paloczi, K.; Kittel, A.; Buzas, E.I.; Ferdinandy, P. Cardioprotection by remote ischemic preconditioning of the rat heart is mediated by extracellular vesicles. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 68, 75–78.

- Yellon, D.M.; Davidson, S.M. Exosomes: Nanoparticles involved in cardioprotection? Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 325–332.

- Timmers, L.; Lim, S.K.; Arslan, F.; Armstrong, J.S.; Hoefer, I.E.; Doevendans, P.A.; Piek, J.J.; El Oakley, R.M.; Choo, A.; Lee, C.N.; et al. Reduction of myocardial infarct size by human mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium. Stem Cell Res. 2007, 1, 129–137.

- Makridakis, M.; Roubelakis, M.G.; Vlahou, A. Stem cells: Insights into the secretome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1834, 2380–2384.

- Arslan, F.; Lai, R.C.; Smeets, M.B.; Akeroyd, L.; Choo, A.; Aguor, E.N.; Timmers, L.; van Rijen, H.V.; Doevendans, P.A.; Pasterkamp, G.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes increase atp levels, decrease oxidative stress and activate pi3k/akt pathway to enhance myocardial viability and prevent adverse remodeling after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2013, 10, 301–312.

- Zhang, H.; Xiang, M.; Meng, D.; Sun, N.; Chen, S. Inhibition of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by exosomes secreted from mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 4328362.

- Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Gao, J.; Chu, Y.; Li, J. Exosomes from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells prevent cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by oxidative stress. Cell. Death Discov. 2019, 5, 79.

- Pu, C.M.; Liu, C.W.; Liang, C.J.; Yen, Y.H.; Chen, S.H.; Jiang-Shieh, Y.F.; Chien, C.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, Y.L. Adipose-derived stem cells protect skin flaps against ischemia/reperfusion injury via il-6 expression. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 1353–1362.

- Liu, J.; Jiang, M.; Deng, S.; Lu, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, P.; Shen, X.; Ruan, H.; Jin, M.; et al. Mir-93-5p-containing exosomes treatment attenuates acute myocardial infarction-induced myocardial damage. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 11, 103–115.

- Xiao, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, X.H.; Yang, X.Y.; Feng, Y.L.; Tan, H.H.; Jiang, L.; Feng, J.; Yu, X.Y. Cardiac progenitor cell-derived exosomes prevent cardiomyocytes apoptosis through exosomal mir-21 by targeting pdcd4. Cell. Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2277.

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Shen, C.; Qin, G.; Ashraf, M.; Weintraub, N.; Ma, G.; Tang, Y. Cardiac progenitor-derived exosomes protect ischemic myocardium from acute ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 431, 566–571.

- Ni, J.; Liu, X.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xu, Y.W.; Liu, Z. Exosomes derived from timp2-modified human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells enhance the repair effect in rat model with myocardial infarction possibly by the akt/sfrp2 pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1958941.

- Yu, B.; Kim, H.W.; Gong, M.; Wang, J.; Millard, R.W.; Wang, Y.; Ashraf, M.; Xu, M. Exosomes secreted from gata-4 overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells serve as a reservoir of anti-apoptotic micrornas for cardioprotection. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 182, 349–360.