Phytoplasmas that are associated with fruit crops, vegetables, cereal and oilseed crops, trees, ornamental, and weeds are increasing at an alarming rate in the Middle East. Up to now, fourteen 16Sr groups of phytoplasma have been identified in association with more than 164 plant species in this region. Peanut witches’ broom phytoplasma strains (16SrII) are the prevalent group, especially in the south of Iran and Gulf states, and have been found to be associated with 81 host plant species. In addition, phytoplasmas belonging to the 16SrVI, 16SrIX, and 16SrXII groups have been frequently reported from a wide range of crops. On the other hand, phytoplasmas belonging to 16SrIV, 16SrV, 16SrX, 16SrXI, 16SrXIV, and 16SrXXIX groups have limited geographical distribution and host range. Twenty-two insect vectors have been reported as putative phytoplasma vectors in the Middle East, of which

Orosius albicinctus

can transmit diverse phytoplasma strains. Almond witches’ broom, tomato big bud, lime witches’ broom, and alfalfa witches’ broom are known as the most destructive diseases.

- Middle East

- phytoplasma diseases

- insect vectors

- 16SrII phytoplasma group

1. Introduction

The Middle East is a transcontinental region that includes Western Asia, Egypt, Iran, and Turkey, and in which agriculture plays a vital economical role. The wide range of temperature fluctuation makes it possible to cultivate a diverse variety of crops, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, cereals, tea, tobacco, and medicinal herbs. In the Middle East, more than 20,000 plant species are grown [1]. Date palm is one of the most important crops in this part of the world. It is widely cultivated in most countries of the Middle East [2]. Among the ten top producers of dates in the world, six countries are from the Middle East (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Oman, and UAE) [2]. Other important crops include wheat, tomatoes, potatoes, sugarcane, maize, sugar beet, and citrus.

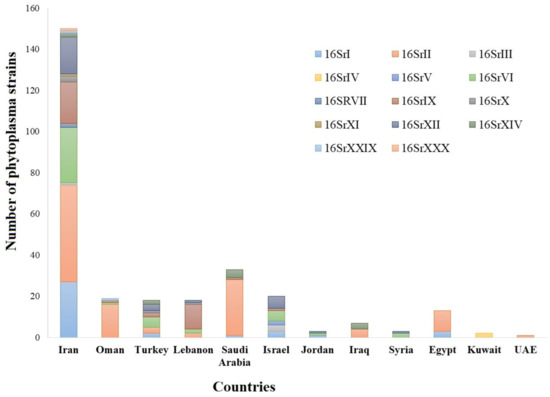

Many plant diseases that are associated with fungi, phytoplasmas, nematodes, viruses, and viroids have been reported in the Middle East [3,4,5,6,7]. Most plant diseases in the Middle East are caused by fungal pathogens [8]. However, the most challenging diseases have been reported as a result of phytoplasma or bacterial diseases [9,10]. Phytoplasmas have been reported in 164 plant species, including vegetables, cereals, fruit crops, medicinal herbs, shade trees, and forage crops. Among the 34 phytoplasma ribosomal groups reported globally, 14 were reported from the Middle Eastern countries (

Many plant diseases that are associated with fungi, phytoplasmas, nematodes, viruses, and viroids have been reported in the Middle East [3][4][5][6][7]. Most plant diseases in the Middle East are caused by fungal pathogens [8]. However, the most challenging diseases have been reported as a result of phytoplasma or bacterial diseases [9][10]. Phytoplasmas have been reported in 164 plant species, including vegetables, cereals, fruit crops, medicinal herbs, shade trees, and forage crops. Among the 34 phytoplasma ribosomal groups reported globally, 14 were reported from the Middle Eastern countries (

and

).

Distribution of phytoplasma groups in countries of the Middle East. The colors represent phytoplasma groups, while the numbers indicate the number of hosts infected by phytoplasmas from each group.

Distribution of phytoplasma groups in different crops, where (

) shows the relative occurrence (%) of phytoplasma diseases according to hosts, while the lateral pies show the relative occurrence (%) of phytoplasma groups on in ornamental crops (

), field crops (

), weeds (

), vegetable crops (

), fruit crops (

), and oilseed crops (

).

Phytoplasmas, which belong to the Mollicutes class, are wall-less pleomorphic phytopathogenic bacteria, annually destroying many economical plant species worldwide [11]. They have a diameter of 200–800 nm [12] and they are found only in the phloem of vascular plants and in the gut and salivary glands of some sap-sucking insects [13,14,15,16]. Phytoplasmas’ membranes usually contain three types of immunodominant protein (IDP): immunodominant membrane protein (Imp), immunodominant membrane protein A (IdpA), and antigenic membrane protein (Amp) [17]. Some IDPs play a role in host–phytoplasma interactions [18]. The Amps interact with leafhoppers microfilament complexes, thus playing a role in determining the specificity of insect vectors to phytoplasmas [19,20,21]. Phytoplasmas can modulate and regulate plant hosts genes, hormones, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis [22]. Phytoplasmas produce proteins, called effectors, which help them overcome plant defenses [23,24]. Effectors help phytoplasmas to multiply in plant hosts, spread by insects, and to modulate plant host growth. Additionally, phytoplasmas secrete effector proteins that alter plant development and enhance plant susceptibility to the insect vectors [14,25].

Phytoplasmas, which belong to the Mollicutes class, are wall-less pleomorphic phytopathogenic bacteria, annually destroying many economical plant species worldwide [11]. They have a diameter of 200–800 nm [12] and they are found only in the phloem of vascular plants and in the gut and salivary glands of some sap-sucking insects [13][14][15][16]. Phytoplasmas’ membranes usually contain three types of immunodominant protein (IDP): immunodominant membrane protein (Imp), immunodominant membrane protein A (IdpA), and antigenic membrane protein (Amp) [17]. Some IDPs play a role in host–phytoplasma interactions [18]. The Amps interact with leafhoppers microfilament complexes, thus playing a role in determining the specificity of insect vectors to phytoplasmas [19][20][21]. Phytoplasmas can modulate and regulate plant hosts genes, hormones, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis [22]. Phytoplasmas produce proteins, called effectors, which help them overcome plant defenses [23][24]. Effectors help phytoplasmas to multiply in plant hosts, spread by insects, and to modulate plant host growth. Additionally, phytoplasmas secrete effector proteins that alter plant development and enhance plant susceptibility to the insect vectors [14][25].

Phytoplasmas can induce disease symptoms, such as witches’ broom, phyllody, reddening and yellowing of leaves, virescence, proliferation of the shoots, and generalized stunting [26]. Some conserved genes, including 16Sr, ribosomal protein (

rp

), elongation factor TU (

tuf

), and translocase protein A and Y, have been utilized to classify them into diverse ribosomal groups and subgroups [27]. To date, 41 ‘

Candidatus

’ species, 33 ribosomal groups, and 160 subgroups were categorized based on RFLP analyses and/or sequencing of the 16S rDNA [28].

The feeding behavior of insect vectors plays an important role in the geographical distribution of phytoplasma strains [29]. In addition, transportation and the use of infected plant material for grafting and planting can result in the spread of phytoplasma diseases [9,30,31]. For example, the 16SrI group phytoplasma strains are transmitted by over 30 species of insect vectors, most of them polyphagous, and they can infect over 100 plant species worldwide, resulting in its vast geographical distribution [28]. On the contrary, phytoplasmas belonging to the coconut lethal yellowing (16SrIV), ash yellows (16SrVII), and apple proliferation (16SrX) groups are distributed in restricted regions and they are transmitted by specific vectors [32,33,34,35]. Plant disease epidemiologists are concerned about the impact of climate change on insect life cycle, as vectors might become more active and introduce phytoplasmas into new areas, hence expanding their geographical distribution [36]. In addition, climate change also has an impact on plants that are grown in a specific area, as it can restrict growth of certain plant species or allow for the introduction or widespread cultivation of new or less common plant species [37]. Given that quarantine measures are not strict in many countries in the Middle East [38,39], the frequent import of ornamental plants and crops from different countries has been associated with the introduction of new pathogens and strains into these countries [7,40]. Although phytoplasmas can evolve to attack new crops [41], limited studies addressed phytoplasma strain evolution in this part of the world. Therefore, data information on epidemic phytoplasmas, their associated host plants, and their vectors in the Middle East are important for quarantine purposes.

The feeding behavior of insect vectors plays an important role in the geographical distribution of phytoplasma strains [29]. In addition, transportation and the use of infected plant material for grafting and planting can result in the spread of phytoplasma diseases [9][30][31]. For example, the 16SrI group phytoplasma strains are transmitted by over 30 species of insect vectors, most of them polyphagous, and they can infect over 100 plant species worldwide, resulting in its vast geographical distribution [28]. On the contrary, phytoplasmas belonging to the coconut lethal yellowing (16SrIV), ash yellows (16SrVII), and apple proliferation (16SrX) groups are distributed in restricted regions and they are transmitted by specific vectors [32][33][34][35]. Plant disease epidemiologists are concerned about the impact of climate change on insect life cycle, as vectors might become more active and introduce phytoplasmas into new areas, hence expanding their geographical distribution [36]. In addition, climate change also has an impact on plants that are grown in a specific area, as it can restrict growth of certain plant species or allow for the introduction or widespread cultivation of new or less common plant species [37]. Given that quarantine measures are not strict in many countries in the Middle East [38][39], the frequent import of ornamental plants and crops from different countries has been associated with the introduction of new pathogens and strains into these countries [7][40]. Although phytoplasmas can evolve to attack new crops [41], limited studies addressed phytoplasma strain evolution in this part of the world. Therefore, data information on epidemic phytoplasmas, their associated host plants, and their vectors in the Middle East are important for quarantine purposes.

2. A Historical Overview of Phytoplasma Diseases in the Middle East

Phytoplasmas are associated with diseases in hundreds of plant species worldwide [29,43,44]. Losses due to phytoplasmas range from negligible effects on the growth to a complete decline of infected plants. Lethal yellowing diseases (LYD) of palms resulted in the death of millions of palms, especially in the Caribbean and Africa [45]. In Europe, apple proliferation, pear decline, and European stone fruit yellows (ESFY) diseases resulted in substantial losses [46]. In China and India, ‘

Phytoplasmas are associated with diseases in hundreds of plant species worldwide [29][42][43]. Losses due to phytoplasmas range from negligible effects on the growth to a complete decline of infected plants. Lethal yellowing diseases (LYD) of palms resulted in the death of millions of palms, especially in the Caribbean and Africa [44]. In Europe, apple proliferation, pear decline, and European stone fruit yellows (ESFY) diseases resulted in substantial losses [45]. In China and India, ‘

Cadidatus Phytoplasma ziziphi’ phytoplasma has been associated with severe outbreaks and losses in jujube, cherry, and peach [47]. Rice orange leaf (ROL) and rice yellow dwarf (RYD) diseases are some of the other common phytoplasma diseases in Asia [48,49].

Phytoplasma ziziphi’ phytoplasma has been associated with severe outbreaks and losses in jujube, cherry, and peach [46]. Rice orange leaf (ROL) and rice yellow dwarf (RYD) diseases are some of the other common phytoplasma diseases in Asia [47][48].

In the Middle East, several phytoplasma diseases are widespread. Some of the diseases only cause significant losses in this part of the world, such as witches’ broom disease of acid lime [50,51], while others are found to be associated with diseases in other parts of the world, such as phytoplasma diseases on almond, stone fruits, tomatoes, carrots, etc. [52,53].

In the Middle East, several phytoplasma diseases are widespread. Some of the diseases only cause significant losses in this part of the world, such as witches’ broom disease of acid lime [49][50], while others are found to be associated with diseases in other parts of the world, such as phytoplasma diseases on almond, stone fruits, tomatoes, carrots, etc. [51][52].

The first observation of a phytoplasma disease in the Middle East dates back to the early 1970s, when witches’ broom disease symptoms were observed on acid lime (

Citrus aurantifolia) in the northern parts of Oman [54,55]. Because they could not confirm the causal agent, a subsequent survey in the early 1980s by J.M. Bové showed that mycoplasma-like organisms (MLO, former name for phytoplasmas) were associated with the disease [56]. In 1987, symptoms of severe witches’ broom were observed on alfalfa in Kerman province in Iran by Rahimian [57]. Witches’ broom of acid lime was reported in the United Arab Emirates in 1989 [58]. No molecular work was done to identify and characterize the associated phytoplasma until 1993 [59]. The first phytoplasma reported in Iran was associated with sesame phyllody [60]. In Israel, research on phytoplasmas started in the 1980s on grapevine, although phytoplasma symptoms have been observed in the 1970s on Bermuda grass and strawberry [61]. In Iraq, the first observation dates back to 2015, when phytoplasma that was associated with Arabic Jasmin was characterized [62]. In Lebanon, a destructive phytoplasma disease on almond was characterized in the early 2000s [63]. In Egypt, the first report of phytoplasma disease was during 2001 with the description of phytoplasma disease symptoms associated with mango [64]. In Saudi Arabia, the first record of a phytoplasma disease was published in 2007 with the description of Al-Wijam, a phytoplasma disease occurring on date palm and associated with 16SrII [65].

) in the northern parts of Oman [53][54]. Because they could not confirm the causal agent, a subsequent survey in the early 1980s by J.M. Bové showed that mycoplasma-like organisms (MLO, former name for phytoplasmas) were associated with the disease [55]. In 1987, symptoms of severe witches’ broom were observed on alfalfa in Kerman province in Iran by Rahimian [56]. Witches’ broom of acid lime was reported in the United Arab Emirates in 1989 [57]. No molecular work was done to identify and characterize the associated phytoplasma until 1993 [58]. The first phytoplasma reported in Iran was associated with sesame phyllody [59]. In Israel, research on phytoplasmas started in the 1980s on grapevine, although phytoplasma symptoms have been observed in the 1970s on Bermuda grass and strawberry [60]. In Iraq, the first observation dates back to 2015, when phytoplasma that was associated with Arabic Jasmin was characterized [61]. In Lebanon, a destructive phytoplasma disease on almond was characterized in the early 2000s [62]. In Egypt, the first report of phytoplasma disease was during 2001 with the description of phytoplasma disease symptoms associated with mango [63]. In Saudi Arabia, the first record of a phytoplasma disease was published in 2007 with the description of Al-Wijam, a phytoplasma disease occurring on date palm and associated with 16SrII [64].

Nowadays, many phytoplasma diseases are being reported from countries in the Middle East. The advances in sequence technology and molecular identification provided by PCR helped to detect 14 16Sr groups of phytoplasma that are associated with 164 plant species (Table S1).

Nowadays, many phytoplasma diseases are being reported from countries in the Middle East. The advances in sequence technology and molecular identification provided by PCR helped to detect 14 16Sr groups of phytoplasma that are associated with 164 plant species.

3. Phytoplasmas Associated with Fruit Crops

Fruit crops are widely grown in the Middle East, with date palms being the most important fruit crop. Other fruit crops include

Citrusspp.,

Prunusspp., grapevines, pomegranates, pears, apples, and bananas.

3.1. Prunus Species

The genus

includes 430 plant species and it is distributed through temperate regions of the world. Nectarine, peach, European plum, almond, Japanese plum, sour cherry, apricot, and sweet cherry are known to be the most economically important

species [28]. Several phytoplasma groups threaten

production. The strains of the 16SrI-B, 16SrII (subgroup II-B, II-C), 16SrVI (subgroup VI-A and VI-D), 16SrIX (IX-B, IX-C, IX-D), 16SrX-F, and 16SrXII-A are the major phytoplasma groups causing economic losses in

species in the Middle East [65][66][67].

Almond witches’ broom (AlmWB) is a destructive disease of stone fruits in Lebanon and Iran [68]. In 2018, Iran was the main almond producer among the Middle Eastern countries, with 139,000 tons of yearly almond production, followed by Turkey (100,000 tons/year) [2]. Witches’-broom of almond (AlmWB) was first observed in Lebanon in the early 1990s and then in Iran in 1995 [62][69][70]. In Iran, AlmWB phytoplasma was primarily reported from almond orchards in the center of Iran and then identified in association with peach and almonds in other regions in Iran [71]. In Lebanon, it has been estimated that this disease destroyed more than 100,000 trees of almond during the outbreak that occurred in 2002, which was attributed to a new strain of phytoplasma [70][72]. The disease was also reported on peach and nectarine in Lebanon and Iran [68][73].

Abou-Jawdah, Karakashian, Sobh, Martini, and Lee [70] revealed that a strain of pigeon pea witches’ broom group was associated with AlmWB in Lebanon. Further studies showed that two different strains, 16SrIX-C and 16SrIX-B, were also associated with AlmWB; the latter was identified as a novel taxon and named ‘

. P. phoenicium’ [11][73]. Both of the subgroups are associated with AlmWB in Iran, while only the 16SrIX-B strain is known as the causal agent of AlmWB in Lebanon [72]. It has been found that all stone fruit trees were only associated with 16SrIX-B in Lebanon and Iran, although phytoplasmas belonging to the 16SrIX-C group are also known to be associated with wild plant species in Lebanon [73]. Abbasi, Hasanzadeh, Zamharir and Tohidfar [65] revealed that, in Iran, sweet orange can be infected by the 16SrIX-B phytoplasma. In addition, further studies revealed that the natural hosts of this strain in Iran include peach, apricot, nectarine, wild almond,

, and

spp. [74][75]. It has also been reported that other phytoplasma groups, including 16SrII-C, 16SrVI-D, and 16SrVII-A, were associated with ALmWB in Iran [76][77].

The 16SrIX-B and 16SrIX-C induce similar symptoms after 1–2 years of infection, including the proliferation of the auxillary branches, leaf yellowing, witches’ broom, severe dieback, the decline of the tree, and loss of production [73]. The main symptoms on nectarine and peach include early bud emergence, little leaves and yellowing, witches’ broom, and phyllody [78]. Zirak, et al. [79] reported that Japanese plum and cherry grown in Iran were associated with aster yellows (16SrI), peanut witches’ broom (16SrII), and stolbur phytoplasma group (16SrXII). Symptoms included yellowing, witches’ broom, proliferation of the shoots, and little leaf [51].

species can also be affected by another phytoplasma disease, namely European stone fruit yellows (ESFY). Plum leptonecrosis, apricot chloritic leaf roll, decline of peach, and plum yellowing are the disease symptoms that are caused by ESFY [80]. The phytoplasmas that are associated with ESFY are strains of ‘

. P. pronurum’ (16SrX-B) [81]. However, strains related to pigeon witches’ broom phytoplasma (16SrIX) have also been reported to be associated with

,

, and

in Iran [76][82]. In Israel, the association between 16SrXII-A and apricot (

) has also been reported [83]. In addition, studies revealed that sweet cherry (

) was associated with ‘

. P. asteris’ in Iran and Turkey [84], ‘

. P. aurantifolia’ in Iran [67], and ‘

. P. trifolii’ in Israel [85]. Phytoplasma strains of 16SrII-B, X-F and XII-A have been reported to be associated with

.

in Iran [67][82]. The association between

and ‘

. P. trifolii’ and 16SrI has been reported in Iran and Jordan, respectively, although the phytoplasma subgroup was not identified in Jordan [86].

Studies that were conducted in Lebanon revealed that the polyphagous leafhopper

is the vector of 16SrIX-B in Lebanon [87]. In addition, this leafhopper has been reported from almond orchards in Iran [88]. Transmission trials by

Dlabola and

Dlabola revealed that they can transmit the 16SrIX-B phytoplasma to peach in Lebanon [89].

and

, collected from

spp. and

, which were grown in the wild in Lebanon, also tested positive to AlmWB phytoplasma strains [89]. However, the vector of AlmWB disease has not been identified in Iran [72][79].

3.2. Pear

Pear decline (PD) is considered to be one of the most destructive pear diseases in the world. ‘

Phytoplasma pyri’ (16SrX-C) is the causal agent of PD and it has been reported in Lebanon and Iran [90]. The typical symptoms of PD include reddening and yellowing of the leaves, stunting, and abnormal foliage [81]. It has been shown that the associated phytoplasma overwinters in the root, so the rootstock cultivar can play a role in the severity of the symptoms. ‘

P. pyri’ (16SrX-C) is the phytoplasma strain that is associated with PD in Iran and Lebanon [90]. In addition, the 16SrI and 16SrX-B phytoplasmas have been reported to be associated with pear decline in Iran [81].

has been confirmed as a phytoplasma vector in Europe and the USA [91]. Although this species has been detected in Iran, no information is available regarding its ability to spread PD phytoplasma.

3.3. Apple

A phytoplasma disease that is similar to apple proliferation (AP) has been observed in apple orchards in Turkey, Lebanon, and Iran. The symptoms included defoliation, yellowing of leaves, enlarged stipules proliferation, small fruits, several small shoots, and decline. Phytoplasma strains that are associated with AP belong to the 16SrI and 16SrII groups in Iran [92], 16SrX-A in Turkey [93], and 16SrIX-C in Lebanon [94]. In addition, an association between 16SrIX-C and a wild apple

exhibiting virescence symptoms has been reported in Lebanon, which suggests that wild apple can work as a reservoir of AP and facilitates its spread [94]. However, little information is available on the relationship between these phytoplasmas strains and apple cultivars.

3.4. Grapevine

Grapevine (

L.) is common in Iran, Turkey, Jordan, and Syria. The most economical phytoplasma disease of grapevine is Flavescence dorée (FD), which is associated with 16SrV-C and 16SrV-D subgroup. This disease is prevalent in many grape-growing areas in Europe, but it has not been detected in the Middle East [95]. Grapevine is known to be a host for several phytoplasmas that cause grapevine yellow (GY). The symptoms of GY include reddening and yellowing in red and white cultivars, necrosis of terminal buds, the appearance of black pustules in infected shoots, downward curling of leaves, and the decline and drying of the berries [96]. Seven phytoplasma groups have been reported associated with GY symptomatic grapevine plants, including the 16SrII-B subgroup in Iran [97], 16SrVI in Syria [98], 16SrI, 16SrIII, and 16SrXII in Israel [60], and 16SrI-B, and 16SrIX in Turkey [99].

Bois noir (BN), which is associated with stolbur phytoplasma strains (subgroup 16SrXII-A, ‘

. P. solani’), is a widespread and significant phytoplasma disease in grapevine which was reported from Iran [100], Turkey [99], and Jordan [101]. It has been confirmed that

is the vector of BN in Europe [102] and, although its presence has been confirmed in vineyards grown in Iran, its ability to transmit BN phytoplasma to healthy plants has not been tested.

Other studies revealed that other phytoplasma groups, such as 16SrI (‘

. P. asteris’), 16SrVII (ash yellows, ‘

. P. fraxini’), and 16SrIX-C (‘

. P. phoenicium’), have been detected in symptomatic grapevines in the center and south of Iran [97][103][104].

The leafhopper

, and

are known as vectors of grapevine yellows in Israel [105].

3.5. Date Palms

Date palm (

L.), which is one of the oldest known fruit crops in the Middle East, is the most important fruit crop in Middle East, North Africa, and Arabian Peninsula. Based on FAO statistics, date palm production reached 8.5 Mt in 2018, with Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Iran being the top producers [2]. The association between date palm and phytoplasma groups 16SrI in Egypt [106], 16SrII in Saudi Arabia [107], and 16SrIV in Kuwait [108] have been documented. The latter is the only record of the 16SrIV group in the Middle East. Recently, the association between 16SrVI and 16SrVII and date palms has been reported in Iran [109], while the 16SrII-D subgroup has been reported to be associated with date palm streak yellows in Oman [110].

3.6. Acid Lime

Witches’ broom disease of lime (WBDL), the most devastating phytoplasma disease infecting Mexican limes, was first observed in Oman in the early 1970s [54]. This disease was then observed in the UAE in 1989 and destroyed many lime orchards in both countries [57]. WBDL was reported in Iran in 1997 and it has been reported in Saudi Arabia in 2009 [111][112]. The infected trees develop a large number of small branches and leaves. The leaves are smaller in size and light green to yellow in color. The symptomatic branches do not usually produce fruits and the infected trees usually die withing four to eight years after the first appearance of symptoms [113]. The disease killed over one million lime trees in Oman and Iran [50].

Other citrus species, like grapefruit, citron, limequat,

,

,

, and, especially, Bakraee, have been reported as hosts of the WBDL phytoplasma in Iran [65][114][115]. In Oman and the UAE, WBDL also infects Palestine sweet lime, citron,

, and sweet limetta [116]. WBDL symptoms were rarely observed on grapefruits [117][118].

P. aurantifolia’, the only member of the 16SrII-B subgroup, is the causal agent for the WBDL disease in Iran as well as in Oman, Saudi Arabia, and UAE [119][120].

In acid lime, the rapid spread of this disease in the infected areas reinforced a hypothesis of involvement of an insect vector. The successful transmission of the phytoplasma by

to Bakraee seedlings was reported by Salehi, Izadpanah, Siampour, Bagheri, and Faghihi [117]. Subsequently, Bagheri, Salehiz, Faghihi, Samavi, and Sadeghi [118] collected 1000

from WBD-affected limes, which were transferred to four healthy acid lime trees (the absence of phytoplasma confirmed by PCR) and covered with an insect-proof net. Three trees developed WBDL symptoms as compared to no symptoms in control trees exposed to 500

that were collected from disease-free fields. Queiroz, et al. [121] reported that the Asian psyllid

could also transmit phytoplasma to healthy plants with an efficiency 20 times lower when compared to

. Hemmati, et al. also confirmed the transmission of phytoplasma to Mexican lime seedlings by

[122].

3.7. Pistachios and Other Fruit Crops

Pistachios (

) is one of the most important fruit crops in Iran, which are mainly exported to other countries. To date, phytoplasmas belonging to the subgroups 16SrII, 16SrIX, and 16SrXII-A have been reported to be associated with pistachio yellows in Iran [123]. Casati et al. (2016) reported that

was affected by 16SrIX-C in Lebanon. Symptoms on pistachios include severe witches’ broom, stunted growth, yellowing, and malformation [123].

Other fruit crops were also reported to be associated with phytoplasma. For example, Salehi, et al. [124] reported that pomegranate (

) was associated with ‘

. P. australasia’ and ‘

. P. pruni’ in central and northeast Iran and phytoplasma belonging to subgroups 16SrII-B and 16SrII-C were reported in Chicoo and Barberry in Iran, respectively [125][126]. A destructive disease, named Nivun Haamir dieback (NHDB), has been reported in association with 16SrXII-A subgroup on papaya (

) in Israel [127].

4. Phytoplasmas Associated with Cereal and Forage Crops

4.1. Cereal Crops

Cereals are staple food in all parts of the world. The most cultivated cereals are wheat, rice, rye, barley, corn, and sorghum. Maize was found to be associated with the 16SrVI-H in Iran and 16SrXIV-A in Turkey [128]. In addition, phytoplasmas belonging to subgroup 16SrVI-A were found in sorghum plants that were grown in northwest of Iran [129].

4.2. Forage Crops

The most known phytoplasma disease of sugarcane is white leaf (SCWL), which is associated with 16SrII strains in Iran [42] and 16SrI strains in Egypt [131]. The stunting of the infected plants, leaf blades with stripped white color, and frail leaf and death of plants are the symptoms of SCWL.

The most known phytoplasma disease of sugarcane is white leaf (SCWL), which is associated with 16SrII strains in Iran [130] and 16SrI strains in Egypt [131]. The stunting of the infected plants, leaf blades with stripped white color, and frail leaf and death of plants are the symptoms of SCWL.

Most countries in the Middle East cultivate Alfalfa (

Medicago sativa L.). The most common disease of alfalfa is alfalfa witches’ broom (AlfWB), which has been reported in several countries. Several phytoplasma groups, including 16SrXII, 16SrVI, 16SrII, and 16SrI, have been reported in association with this disease in the Middle East. The symptoms of the disease include little leaves, stunting, witches’ broom, decline, and plant death [57,132]. Phytoplasma strains of the 16SrII group are the major causal agents of AlfWB in the Middle East. Indeed, only phytoplasma strains of the 16SrII-D subgroup were associated with AlfWB in Oman, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia [132,133,134]. However, 16SrXII has been reported from several alfalfa fields in Iran [135]. Esmailzadeh-Hosseini, et al. [136] confirmed that

L.). The most common disease of alfalfa is alfalfa witches’ broom (AlfWB), which has been reported in several countries. Several phytoplasma groups, including 16SrXII, 16SrVI, 16SrII, and 16SrI, have been reported in association with this disease in the Middle East. The symptoms of the disease include little leaves, stunting, witches’ broom, decline, and plant death [56][132]. Phytoplasma strains of the 16SrII group are the major causal agents of AlfWB in the Middle East. Indeed, only phytoplasma strains of the 16SrII-D subgroup were associated with AlfWB in Oman, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia [132][133][134]. However, 16SrXII has been reported from several alfalfa fields in Iran [135]. Esmailzadeh-Hosseini, et al. [136] confirmed that

O. albicinctus

is the vector of the 16SrII phytoplasmas causing AlfWB in Iran. In addition, weed species, including

Cardaria draba

and

Prosopis fracta, known preferred hosts for vectors, have also been identified as alternative hosts of the 16SrII phytoplasmas causing AlfWB [57].

, known preferred hosts for vectors, have also been identified as alternative hosts of the 16SrII phytoplasmas causing AlfWB [56].

References

- Moghaddam, V.K.; Changani, F.; Mohammadi, A.; Hadei, M.; Ashabi, R.; Majd, L.E.; Mahvi, A.H. Sustainable development of water resources based on wastewater reuse and upgrading of treatment plants: A review in the Middle East. Desalin. Water Treat. 2017, 65, 463–473.

- FAO. FAOSTAT. Available online: (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Kolmer, J.A.; Herman, A.; Ordoñez, M.E.; German, S.; Morgounov, A.; Pretorius, Z.; Visser, B.; Anikster, Y.; Acevedo, M. Endemic and panglobal genetic groups, and divergence of host-associated forms in worldwide collections of the wheat leaf rust fungus Puccinia triticina as determined by genotyping by sequencing. Heredity 2020, 124, 397–409.

- Kumar, S.; Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Siampour, M.; Sobh, H.; Tedeschi, R.; Alma, A.; Bianco, P.A.; Quaglino, F. Genetic diversity of ‘Candidatus phytoplasma phoenicium’ strain populations associated with almond witches’ broom in Lebanon and Iran. Phytopathogenic Mollicutes 2019, 9, 217–218.

- Donkersley, P.; Silva, F.W.S.; Carvalho, C.M.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Elliot, S.L. Biological, environmental and socioeconomic threats to citrus lime production. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2018, 125, 339–356.

- Alhudaib, K.A.; Rezk, A.A.; Soliman, A.M. Current status of watermelon chlorotic stunt virus (WmCSV) on some cucurbit plants (Cucurbitaceae) in Alahsa region of Saudi Arabia. Sci. J. King Faisal Univ. 2018, 19, 37–45.

- Al-Harthi, S.A.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Al-Saady, A.A. Potential of citrus budlings originating in the Middle East as sources of citrus viroids. Crop Prot. 2013, 48, 13–15.

- Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Al-Kharousi, M.; Al-Saady, N.A.; Hyde, K.D. A checklist of fungi in Oman. Phytotaxa 2016, 273, 219–261.

- Al-Sadi, A.M.; Al-Moqbali, H.S.; Al-Yahyai, R.A.; Al-Said, F.A. AFLP data suggest a potential role for the low genetic diversity of acid lime (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle) in Oman in the outbreak of witches’ broom disease of lime. Euphytica 2012, 188, 285–297.

- Mardi, M.; Nekouei, S.M.K.; Farsad, L.K.; Ehya, F.; Shabani, M.; Shafiee, M.; Tabatabaei, M.; Safarnejad, M.R.; Jouzani, G.S.; Salekdeh, G.H. Witches’ broom disease of Mexican lime trees: Disaster to be addressed before it will be too late. Bull. Insectol. 2011, 64, S205–S206.

- Firrao, G.; Andersen, M.; Bertaccini, A.; Boudon, E.; Bové, J.M.; Daire, X.; Davis, R.E.; Fletcher, J.; Garnier, M.; Gibb, K.S.; et al. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma’, a taxon for the wall-less, non-helical prokaryotes that colonize plant phloem and insects. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1243–1255.

- Doi, Y.; Teranaka, M.; Yora, K.; Asuyama, H. Mycoplasma or PLT group-like micro-organisms found in the phloem element of plants infected with mulberry dwarf, potato witches’ broom, aster yellows or Paulownia witches’ broom. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 1967, 33, 259–266.

- Hill, G.; Sinclair, W. Taxa of leafhoppers carrying phytoplasmas at sites of ash yellows occurrence in New York State. Plant Dis. 2000, 84, 134–138.

- Sugio, A.; MacLean, A.M.; Kingdom, H.N.; Grieve, V.M.; Manimekalai, R.; Hogenhout, S.A. Diverse targets of phytoplasma effectors: From plant development to defense against insects. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2011, 49, 175–195.

- Ammar, E.; Hogenhout, S. Mollicutes associated with arthropods and plants. Insect Symbiosis 2006, 2, 97–118.

- Weintraub, P.G.; Beanland, L. Insect vectors of phytoplasmas. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2006, 51, 91–111.

- Kakizawa, S.; Oshima, K.; Namba, S. Diversity and functional importance of phytoplasma membrane proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2006, 14, 254–256.

- Kakizawa, S.; Oshima, K.; Ishii, Y.; Hoshi, A.; Maejima, K.; Jung, H.-Y.; Yamaji, Y.; Namba, S. Cloning of immunodominantmembrane protein genes of phytoplasmas and their in planta expression. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 293, 92–101.

- Suzuki, S.; Oshima, K.; Kakizawa, S.; Arashida, R.; Jung, H.-Y.; Yamaji, Y.; Nishigawa, H.; Ugaki, M.; Namba, S. Interaction between the membrane protein of a pathogen and insect microfilament complex determines insect-vector specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 4252–4257.

- Ishii, Y.; Kakizawa, S.; Hoshi, A.; Maejima, K.; Kagiwada, S.; Yamaji, Y.; Oshima, K.; Namba, S. In the non-insect-transmissible line of onion yellows phytoplasma (OY-NIM), the plasmid-encoded transmembrane protein ORF3 lacks the major promoter region. Microbiology 2009, 155, 2058–2067.

- Galetto, L.; Bosco, D.; Balestrini, R.; Genre, A.; Fletcher, J.; Marzachì, C. The major antigenic membrane protein of “Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris” selectively interacts with ATP synthase and actin of leafhopper vectors. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22571.

- Sugio, A.; Kingdom, H.; MacLean, A.; Grieve, V.; Hogenhout, S. Phytoplasma protein effector SAP11 enhances insect vector reproduction by manipulating plant development and defense hormone biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, E1254–E1263.

- Sugio, A.; MacLean, A.M.; Hogenhout, S.A. The small phytoplasma virulence effector SAP11 contains distinct domains required for nuclear targeting and CIN-TCP binding and destabilization. New Phytol. 2014, 202, 838–848.

- Orlovskis, Z. Role of Phytoplasma Effector Proteins in Plant Development and Plant-Insect Interactions; University of East Anglia: Norwich, UK, 2017.

- Sugio, A.; Hogenhout, S.A. The genome biology of phytoplasma: Modulators of plants and insects. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2012, 15, 247–254.

- Du Toit, A. Bacterial pathogenicity: Phytoplasma converts plants into zombies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 393.

- Lee, I.M.; Gundersen-Rindal, D.E.; Bertaccini, A. Phytoplasma: Ecology and genomic diversity. Phytopathology 1998, 88, 1359–1366.

- Bertaccini, A.; Lee, I.M. Phytoplasmas: An update. In Phytoplasmas: Plant Pathogenic Bacteria—I: Characterisation and Epidemiology of Phytoplasma—Associated Diseases; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1–29.

- Hogenhout, S.A.; Oshima, K.; AMMAR, E.D.; Kakizawa, S.; Kingdom, H.N.; Namba, S. Phytoplasmas: Bacteria that manipulate plants and insects. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 9, 403–423.

- Mazraie, M.A.; Izadpanah, K.; Hamzehzarghani, H.; Salehi, M.; Faghihi, M.M. Spread and colonization pattern of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma aurantifolia’ in lime plants [Citrus aurantifolia (Christm.) Swingle] as revealed by real-time PCR assay. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 101, 629–637.

- Caglayan, K.; Gazel, M.; Škorić, D. Transmission of phytoplasmas by agronomic practices. In Phytoplasmas: Plant Pathogenic Bacteria—II: Transmission and Management of Phytoplasma—Associated Diseases; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 149–163.

- Foissac, X.; Wilson, M. Current and possible future distributions of phytoplasma diseases and their vectors. In Phytoplasmas: Genomes, Plant Hosts, and Vectors; Weintraub, P.G., Jones, P., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2010; pp. 309–324.

- Bila, J.; Mondjana, A.; Santos, L.; Högberg, N. Coconut lethal yellowing disease and the oryctes monoceros beetle: A joint venture against coconut production in Mozambique. Phytopathogenic Mollicutes 2019, 9, 153–154.

- Alma, A.; Lessio, F.; Nickel, H. Insects as phytoplasma vectors: Ecological and epidemiological aspects. In Phytoplasmas: Plant Pathogenic Bacteria—II: Transmission and Management of Phytoplasma—Associated Diseases; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–25.

- Solomon, J.J.; Hegde, V.; Babu, M.; Geetha, L. Phytoplasmal diseases. In The Coconut Palm (Cocos nucifera L.)—Research and Development Perspectives; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 519–556.

- Jones, R.A.; Barbetti, M.J. Influence of climate change on plant disease infections and epidemics caused by viruses and bacteria. Cab Rev. Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2012, 22, 1–31.

- Classen, A.T.; Sundqvist, M.K.; Henning, J.A.; Newman, G.S.; Moore, J.A.M.; Cregger, M.A.; Moorhead, L.C.; Patterson, C.M. Direct and indirect effects of climate change on soil microbial and soil microbial-plant interactions: What lies ahead? Ecosphere 2015, 6, 1–21.

- Al-Sadi, A.M.; Al-Hilali, S.A.; Al-Yahyai, R.A.; Al-Said, F.A.; Deadman, M.L.; Al-Mahmooli, I.H.; Nolasco, G. Molecular characterization and potential sources of Citrus tristeza virus in Oman. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 632–640.

- Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Sobh, H.; Akkary, M. First report of Almond witchesbroom phytoplasma (Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium) causing a severe disease on nectarine and peach trees in Lebanon. Eppo Bull. 2009, 39, 94–98.

- Casati, P.; Quaglino, F.; Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Picciau, L.; Cominetti, A.; Tedeschi, R.; Jawhari, M.; Choueiri, E.; Sobh, H.; Molino Lova, M.; et al. Wild plants could play a role in the spread of diseases associated with phytoplasmas of pigeon pea witches’-broom group (16SrIX). J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 98, 71–81.

- Mall, S.; Rao, G.P.; Marcone, C. Phytoplasma diseases of weeds: Detection, taxonomy and diversity. In Recent Trends in Biotechnology and Microbiology; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 87–108.

- Lee, I.M.; Davis, R.E.; Gundersen-Rindal, D.E. Phytoplasma: Phytopathogenic mollicutes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000, 54, 221–255.

- Bertaccini, A. Phytoplasmas: Diversity, taxonomy, and epidemiology. Front. Biosci. 2007, 12, 673–689.

- Gurr, G.M.; Johnson, A.C.; Ash, G.J.; Wilson, B.A.; Ero, M.M.; Pilotti, C.A.; Dewhurst, C.F.; You, M.S. Coconut lethal yellowing diseases: A phytoplasma threat to palms of global economic and social significance. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1521.

- Seemüller, E.; Schneider, B. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma mali’, ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pyri’ and ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma prunorum’, the causal agents of apple proliferation, pear decline and European stone fruit yellows, respectively. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1217–1226.

- Zhu, S.; Bertaccini, A.; Lee, I.; Paltrinieri, S.; Hadidi, A. Cherry Lethal Yellows and Decline Phytoplasmas. In Virus and Virus-Like Diseases of Pome and Stone Fruits; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2011; pp. 255–257.

- Li, S.; Hao, W.; Lu, G.; Huang, J.; Liu, C.; Zhou, G. Occurrence and Identification of a New Vector of Rice Orange Leaf Phytoplasma in South China. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 1483–1487.

- Zhu, Y.; He, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, G. Draft Genome Sequence of Rice Orange Leaf Phytoplasma from Guangdong, China. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e00430-17.

- Hemmati, C.; Nikooei, M.; Al-Sadi, A.M. Five decades of research on phytoplasma-induced witches’ broom diseases. Cab Rev. 2021, 16, 1–16.

- Al-Ghaithi, A.G.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Al-Hammadi, M.S.; Al-Shariqi, R.M.; Al-Yahyai, R.A.; Al-Mahmooli, I.H.; Carvalho, C.M.; Elliot, S.L.; Hogenhout, S. Expression of phytoplasma-induced witches’ broom disease symptoms in acid lime (Citrus aurantifolia) trees is affected by climatic conditions. Plant Pathol. 2017, 66, 1380–1388.

- Zirak, L.; Bahar, M.; Ahoonmanesh, A. Molecular characterization of phytoplasmas associated with peach diseases in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2010, 158, 105–110.

- Molino Lova, M.; Quaglino, F.; Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Choueiri, E.; Tedeschi, R.; Casati, P.; Bianco, P. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’-related strains infecting almond, peach and nectarine in Lebanon. Bull. Insectol. 2011, 64, S267–S268.

- Bridge, J.; Waller, J.M. Report on a Visit to the Sultanate of Oman to Review Plant Disease and Nematode Problems; Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries: Muscat, Oman, 1974.

- Waller, J.; Bridge, J. Plant diseases and nematodes in the Sultanate of Oman. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 24, 313–326.

- Bové, J.; Garnier, M.; Mjeni, A.; Khayrallah, A. Witches’ Broom Disease of Small-Fruited Acid Lime Trees in Oman: First MLO Disease of Citrus. In International Organization of Citrus Virologists Conference Proceedings (1957–2010); University of California: Riverside, CA, USA, 1988.

- Esmailzadeh Hosseini, S.; Salehi, M.; Khodakaramian, G.; Mirchenari, S.M.; Bertaccini, A. An up to date status of alfalfa witches’ broom disease in Iran. Phytopathogenic Mollicutes 2015, 5, 9–18.

- Garnier, M.; Zreik, L.; Bové, J.M. Witches’ broom, a lethal mycoplasmal disease of lime trees in the Sultanate of Oman and the United Arab Emirates. Plant Dis. 1991, 75, 546–551.

- Salehi, M.; Izadpanah, K. A comparative study of transmission, host range and symptomatology of sesame phyllody and alfalfa witches broom. Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 1993, 29, 157–158.

- Salehi, M.; Izadpanah, K. Etiology and transmission of sesame phyllody in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 1992, 135, 37–47.

- Orenstein, S.; Zahavi, T.; Weintraub, P. Distribution of phytoplasma in grapevines in the Golan Heights, Israel, and development of a new universal primer. Vitis 2001, 40, 219–223.

- Alkuwaiti, N.A.S.; Kareem, T.A.; Sabier, L.J. Molecular detection of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma australasia’ and ‘Ca. P. cynodontis’ in Iraq. Agriculture 2017, 63, 112–119.

- Choueiri, E.; Jreijiri, F.; Issa, S.; Verdin, E.; Bové, J.; Garnier, M. First report of a phytoplasma disease of almond (Prunus amygdalus) in Lebanon. Plant Dis. 2001, 85, 802.

- El-Banna, O.-H.M.; El-Deeb, S. First record of phytoplasma associated with malformed mango inflorescences in Egypt. Egypt J. Phytopathol. 2001, 29, 101–102.

- Alhudaib, K.; Arocha, Y.; Wilson, M.; Jones, P. “Al-Wijam”, a new phytoplasma disease of date palm in Saudi Arabia. Bull. Insectol. 2007, 60, 285–286.

- Abbasi, A.; Hasanzadeh, N.; Zamharir, M.G.; Tohidfar, M. Identification of a group 16SrIX ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’ phytoplasma associated with sweet orange exhibiting decline symptoms in Iran. Asutralas. Plant Dis. Notes 2019, 14, 11.

- Salehi, M.; Salehi, E.; Siampour, M.; Esmailzadeh-Hosseini, S.A.; Quaglino, F.; Bianco, P.A. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’ associated with apricot yellows and peach witches’ broom in Iran. Phytopathogenic Mollicutes 2019, 9, 215–216.

- Zirak, L.; Bahar, M.; Ahoonmanesh, A. Molecular characterization of phytoplasmas related to peanut witches’ broom and stolbur groups infecting plum in Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 2009, 91, 713–716.

- Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Dakhil, H.; El-Mehtar, S.; Lee, I.M. Almond witches’-broom phytoplasma: A potential threat to almond, peach, and nectarine. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2003, 25, 28–32.

- Salehi, M.; Izadpanah, K. Almond brooming. Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 1995, 32, 111–112.

- Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Karakashian, A.; Sobh, H.; Martini, M.; Lee, I.M. An epidemic of almond witches’-broom in Lebanon: Classification and phylogenetic relationships of the associated phytoplasma. Plant Dis. 2002, 86, 477–484.

- Salehi, M.; Haghshenas, F.; Khanchezar, A.; Esmailzadeh-Hosseini, S.A. Association of ‘candidatus phytoplasma phoenicium’ with Gf-677 witches’ broom in Iran. Bull. Insectol. 2011, 64, S113–S114.

- Salehi, M.; Izadpanah, K.; Heydarnejad, J. Characterization of a new almond witches’ broom phytoplasma in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2006, 154, 386–391.

- Lova, M.M.; Quaglino, F.; Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Choueiri, E.; Sobh, H.; Casati, P.; Tedeschi, R.; Alma, A.; Bianco, P.A. Identification of new 16SrIX subgroups, -F and -G, among ‘Candidatus phytoplasma phoenicium’ strains infecting almond, peach and nectarine in Lebanon. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2011, 50, 273–282.

- Motamedi, E.; Salehi, M.; Sabbagh, S.K.; Salari, M. Differentiation and classification of phytoplasmas associated with almond and GF-677 witches’-broom diseases using rRNA and rp Genes. J. Phytopathol. 2016, 164, 185–192.

- Salehi, M.; Esmailzadeh Hosseini, S.A.; Salehi, E.; Quaglino, F.; Bianco, P.A. Peach witches’-broom, an emerging disease associated with ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’ and ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma aurantifolia’ in Iran. Crop Prot. 2020, 127, 104946.

- Salehi, M.; Salehi, E.; Abbasian, M.; Izadpanah, K. Wild almond (Prunus scoparia), a potential source of almond witches’ broom phytoplasma in Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 2015, 97, 377–381.

- Zirak, L.; Bahar, M.; Ahoonmanesh, A. Characterization of phytoplasmas associated with almond diseases in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2009, 157, 736–741.

- Verdin, E.; Salar, P.; Danet, J.L.; Choueiri, E.; Jreijiri, F.; El Zammar, S.; Gélie, B.; Bové, J.M.; Garnier, M. ‘Candidatus phytoplasma phoenicium’ sp. nov., a novel phytoplasma associated with an emerging lethal disease of almond trees in Lebanon and Iran. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 833–838.

- Zirak, L.; Bahar, M.; Ahoonmanesh, A. Characterization of phytoplasmas related to ‘Candidatus phytoplasma asteris’ and peanut WB group associated with sweet cherry diseases in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2010, 158, 63–65.

- Salehi, M.; Salehi, E.; Siampour, M.; Quaglino, F.; Bianco, P.A. Apricot yellows associated with ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’ in Iran. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2018, 57, 269–283.

- Hashemi-Tameh, M.; Bahar, M.; Zirak, L. Molecular characterization of phytoplasmas related to apple proliferation and aster yellows groups associated with pear decline disease in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2014, 162, 660–669.

- Allahverdi, T.; Rahimian, H.; Babaeizad, V. Prevalence and distribution of peach yellow leaf roll in North of Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 96, 603.

- Gera, A.; Maslenin, L.; Weintraub, P.G.; Weintraub, M. Phytoplasma and spiroplasma diseases in open-field crops in Israel. Bull. Insectol. 2011, 64, S53–S54.

- Çaglayan, K.; Gazel, M.; Küçükgöl, C.; Paltrineri, S.; Contaldo, N.; Bertaccini, A. First report of ‘candidatus phytoplasma asteris’ (group 16sri-b) infecting sweet cherries in Turkey. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 95, 77.

- Weintraub, P.G.; Zeidan, M.; Spiegel, S.; Gera, A. Diversity of the known phytoplasmas in Israel. Bull. Insectol. 2007, 60, 143.

- Anfoka, G.H.; Fattash, I. Detection and identification of aster yellows (16SrI) phytoplasma in peach trees in Jordan by RFLP analysis of PCR-amplified products (16S rDNAs). J. Phytopathol. 2004, 152, 210–214.

- Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Dakhil, H.; Lova, M.M.; Sobh, H.; Nehme, M.; Fakhr-Hammad, E.A.; Alma, A.; Samsatly, J.; Jawhari, M.; Abdul-Nour, H.; et al. Preliminary survey of potential vectors of ‘Candidatus phytoplasma phoenicium’ in lebanon and probability of occurrence of apricot chlorotic leaf roll (ACLR) phytoplasma. Bull. Insectol. 2011, 64, S123–S124.

- Mozaffarian, F.; Wilson, A.M. A checklist of the leafhoppers of Iran (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha: Cicadellidae). Zootaxa 2016, 4062, 152–165.

- Tedeschi, R.; Picciau, L.; Quaglino, F.; Abou-Jawdah, Y.; Molino Lova, M.; Jawhari, M.; Casati, P.; Cominetti, A.; Choueiri, E.; Abdul-Nour, H.; et al. A cixiid survey for natural potential vectors of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’ in Lebanon and preliminary transmission trials. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2015, 166, 372–388.

- Salehi, M.; Izadpanah, K.; Taghayi, S.M.; Rahimian, H. Characterization of a phytoplasma associated with pear decline in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2008, 156, 493–495.

- Riedle-Bauer, M.; Paleskić, C.; Schwanzer, J.; Kölber, M.; Bachinger, K.; Antonielli, L.; Schönhuber, C.; Elek, R.; Stradinger, J.; Emberger, M.; et al. Epidemiological and molecular study on ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma prunorum’ in Austria and Hungary. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2019, 175, 400–414.

- Hashemi-Tameh, M.; Bahar, M.; Zirak, L. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’ and ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma aurantifolia’, New Phytoplasma Species Infecting Apple Trees in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2014, 162, 472–480.

- Canik, D.; Ertunc, F. Distribution and molecular characterization of apple proliferation phytoplasma in Turkey. Bull. Insectol. 2007, 60, 335–336.

- Salar, P.; Choueiri, E.; Jreijiri, F.; El Zammar, S.; Danet, J.L.; Foissac, X. Phytoplasmas in Lebanon: Characterization of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pyri’ and stolbur phytoplasma respectively associated with pear decline and grapevine “bois noir” diseases. Bull. Insectol. 2007, 60, 357–358.

- Bertaccini, A.; Duduk, B. Phytoplasma and phytoplasma diseases: A review of recent research. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2009, 48, 355–378.

- Salehi, E.; Salehi, M.; Taghavi, S.M.; Izadpanah, K. First report of a 16SrIX group (Pigeon pea witches’-broom) phytoplasma associated with grapevine yellows in Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 98, 376.

- Ghayeb Zamharir, M.; Paltrinieri, S.; Hajivand, S.; Taheri, M.; Bertaccini, A. Molecular identification of diverse ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma’ species associated with grapevine decline in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2017, 165, 407–413.

- Contaldo, N.; Soufi, Z.; Bertaccini, A. Preliminary identification of phytoplasmas associated with grapevine yellows in Syria. Bull. Insectol. 2011, 64, S217–S218.

- Canik, D.; Ertunc, F.; Paltrinieri, S.; Contaldo, N.; Bertaccini, A. Identification of different phytoplasmas infecting grapevine in Turkey. Bull. Insectol. 2011, 64, S225–S226.

- Mirchenari, S.M.; Massah, A.; Zirak, L. Bois noir: New phytoplasma disease of grapevine in Iran. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2015, 55, 88–93.

- Salem, N.M.; Quaglino, F.; Abdeen, A.; Casati, P.; Bulgari, D.; Alma, A.; Bianco, P.A. First Report of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma solani’ Strains Associated with Grapevine Bois Noir in Jordan. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 1505.

- Quaglino, F.; Sanna, F.; Moussa, A.; Faccincani, M.; Passera, A.; Casati, P.; Bianco, P.A.; Mori, N. Identification and ecology of alternative insect vectors of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma solani’ to grapevine. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19522.

- Ghayeb Zamharir, M.; Taheri, M. Effect of new resistance inducers on grapevine phytoplasma disease. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2019, 52, 1207–1214.

- Babaei, G.; Esmaeilzadeh-Hosseini, S.A.; Eshaghi, R.; Nikbakht, V. Incidence and molecular characterization of a 16SrI-B phytoplasma strain associated with Vitis vinifera leaf yellowing and reddening in the west of Iran. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 41, 468–474.

- Klein, M.; Weintraub, P.; Davidovich, M.; Kuznetsova, L.; Zahavi, T.; Ashanova, A.; Orenstein, S.; Tanne, E. Monitoring phytoplasma-bearing leafhoppers/planthoppers in vineyards in the Golan Heights, Israel. J. Appl. Entomol. 2001, 125, 19–23.

- Alkhazindar, M. Detection and molecular identification of aster yellows phytoplasma in date palm in Egypt. J. Phytopathol. 2014, 162, 621–625.

- Al-Awadhi, H. Molecular and microscopical detection of phytoplasma associated with yellowing disease of date palms Phoenix dactylifera L. in Kuwait. Kuwait J. Sci. Eng. 2002, 29, 87–109.

- Alhudaib, K.; Arocha, Y.; Wilson, M.; Jones, P. First report of a 16SrI, Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris group phytoplasma associated with a date palm disease in Saudi Arabia. Plant Pathol. 2008, 57, 366.

- Ghayeb Zamharir, M.; Eslahi, M.R. Molecular study of two distinct phytoplasma species associated with streak yellows of date palm in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2019, 167, 19–25.

- Hemmati, C.; Al-Subhi, A.M.; Al-Housni, M.T.; Al-Sadi, A.M. Molecular detection and characterization of a 16SrII-D phytoplasma associated with streak yellows of date palm in Oman. Asutralas. Plant Dis. Notes 2020, 15, 35.

- Alhudaib, K.; Arocha, Y.; Wilson, M.; Jones, P. Molecular identification, potential vectors and alternative hosts of the phytoplasma associated with a lime decline disease in Saudi Arabia. Crop Prot. 2009, 28, 13–18.

- Bove, J.M.; Danet, J.L.; Bananej, K.; Hassanzadeh, N.; Taghizadeh, M.; Salehi, M.; Garnier, M. Witches’ broom disease of lime (WBDL) in Iran. In International Organization of Citrus Virologists Conference Proceedings (1957–2010); University of California: Riverside, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 207–212.

- Al-Yahyai, R.A.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Al-Said, F.A.J.; Alkalbani, Z.H.; Carvalho, C.M.; Elliot, S.L.; Bertaccini, A. Development and morphological changes in leaves and branches of acid lime (Citrus aurantifolia) affected by witches’ broom. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2015, 54, 133–139.

- Djavaheri, M.; Rahimian, H. Witches’-broom of bakraee (Citrus reticulata hybrid) in iran. Plant Dis. 2004, 88, 683.

- Faghihi, M.; Bagheri, A.; Askari Seyahooei, M.; Pezhman, A.; Faraji, G. First report of a ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma aurantifolia’-related strain associated with witches’-broom disease of limequat in Iran. New Dis. Rep. 2017, 35, 24.

- Al-Subhi, A.M.; Al-Yahyai, R.A.; Al-Sadi, A.M. First report of a ‘Candidatus phytoplasma aurantifolia’-related strain in citrus macrophylla in Oman. Phytopathogenic Mollicutes 2019, 9, 7–8.

- Salehi, M.; Izadpanah, K.; Siampour, M.; Bagheri, A.; Faghihi, S.M. Transmission of ‘candidatus phytoplasma aurantifolia’ to bakraee (Citrus reticulata hybrid) by feral Hishimonus phycitis leafhoppers in Iran. Plant Dis. 2007, 91, 466.

- Bagheri, A.N.; Salehiz, M.; Faghihi, M.M.; Samavi, S.; Sadeghi, A. Transmission of ‘Candidatus phytoplasma aurantifolia’ to Mexican lime by the leafhopper Hishimonus phycitys in Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 2009, 91, 105.

- Zreik, L.; Carle, P.; Bove, J.M.; Garnier, M. Characterization of the mycoplasmalike organism associated with Witches’- broom disease of lime and proposition of a Candidatus taxon for the organism, ‘Candidatus phytoplasma aurantifolia’. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1995, 45, 449–453.

- Lee, I.-M.; Gundersen-Rindal, D.E.; Davis, R.E.; Bartoszyk, L.M. Revised classification scheme of phytoplasmas based on RFLP analyses of 16s rRNA and ribosomal protein gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1998, 48, 1153–1169.

- Queiroz, R.B.; Donkersley, P.; Silva, F.N.; Al-Mahmmoli, I.H.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Carvalho, C.M.; Elliot, S.L. Invasive mutualisms between a plant pathogen and insect vectors in the middle East and Brazil. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160557.

- Hemmati, C.; Seyahooei, M.A.; Nikooei, M.; Najafabadi, S.S.M.; Goodarzi, A.; Mazraie, M.A.; Faghihi, M.M. Vector transmission of lime witches’ broom phytoplasma to mexican lime seedlings under greenhouse condition. J. Crop Prot. 2020, 9, 209–215.

- Ghayeb Zamharir, M. Molecular study of phytoplasmas associated with pistachio yellows in Iran. J. Phytopathol. 2018, 166, 161–166.

- Salehi, M.; Esmailzadeh Hosseini, S.A.; Rasoulpour, R.; Salehi, E.; Bertaccini, A. Identification of a phytoplasma associated with pomegranate little leaf disease in Iran. Crop Prot. 2016, 87, 50–54.

- Tavanaei, S.R.; Shams Bakhsh, M.; Akbari Motlagh, M. The first report pf a phytoplasma associated with Barberry (Berberis vulgaris) stem fasciation in Iran. In Proceedings of the 22nd Iranian Plant Protection Congress, Tehran, Iran, 27–30 August 2016.

- Bagheri, A.; Faghihi, M.M.; Khankahdani, H.H.; Seyahooei, M.A.; Ghanbari, N.; Sarbijan, S.S. First report of a phytoplasma associated with sapodilla flattened stem disease in Iran. Asutralas. Plant Dis. Notes 2017, 12, 25.

- Gera, A.; Mawassi, M.; Zeidan, M.; Spiegel, S.; Bar-Joseph, M. An isolate of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma australiense’ group associated with Nivun Haamir dieback disease of papaya in Israel. Plant Pathol. 2005, 54, 560.

- Çağlar, B.K.; Satar, S.; Bertaccini, A.; Elbeaino, T. Detection and seed transmission of Bermudagrass phytoplasma in maize in Turkey. J. Phytopathol. 2019, 167, 248–255.

- Zibadoost, S.; Rastgou, M. Molecular identification of phytoplasmas associated with some weeds in West Azarbaijan province, Iran. Acta Agric. Slov. 2016, 107, 129–136.

- Siampour, M.; Izadpanah, K.; Salehi, M.; Afsharifar, A. Occurrence and Distribution of Phytoplasma Diseases in Iran. In Sustainable Management of Phytoplasma Diseases in Crops Grown in the Tropical Belt; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 47–86.

- Elsayed, A.I.; Boulila, M. Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of Sugarcane Yellow Leaf Phytoplasma (SCYLP) in Egypt. J. Phytopathol. 2014, 162, 89–97.

- Khan, A.J.; Botti, S.; Al-Subhi, A.M.; Gundersen-Rindal, D.E.; Bertaccini, A.F. Molecular identification of a new phytoplasma associated with alfalfa witches’-broom in Oman. Phytopathology 2002, 92, 1038–1047.

- Al-Saleh, M.A.; Amer, M.A.; Al-Shahwan, I.M.; Abdalla, O.A.; Damiri, B.V. Detection and molecular characterization of alfalfa witches’-broom phytoplasma and its leafhopper vector in riyadh region of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2014, 16, 300–306.

- Al-Kuwaiti, N.; Kareem, T.; Sadaq, F.H.; Al-Aadhami, L.H. First report of phytoplasma detection on sand olive, cowpea and alfalfa in Iraq. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2019, 59, 428–431.

- Salehi, M.; Izadpanah, K.; Siampour, M.; Esmailzadeh-Hosseini, S.A. Polyclonal antibodies for the detection and identification of fars alfalfa witches’ broom phytoplasma. Bull. Insectol. 2011, 64, S59–S60.

- Esmailzadeh-Hosseini, S.A.; Salehi, M.; Mirzaie, A. Alternate hosts of alfalfa witches’ broom phytoplasma and winter hosts of its vector orosius albicinctus in Yazd-Iran. Bull. Insectol. 2011, 64, S247–S248.