Plant-beneficial Pseudomonas spp. aggressively colonize the rhizosphere and produce numerous secondary metabolites, such as 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG). DAPG is a phloroglucinol derivative that contributes to disease suppression, thanks to its broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. A famous example of this biocontrol activity has been previously described in the context of wheat monoculture where a decline in take-all disease (caused by the ascomycete Gaeumannomyces tritici) has been shown to be associated with rhizosphere colonization by DAPG-producing Pseudomonas spp.

- 2

- 4-diacetylphloroglucinol

- DAPG

- Pseudomonas

- biocontrol

- antibiotic

1. Introduction

Phloroglucinol derivatives are a large class of secondary metabolites widely distributed in plants and brown algae. Over a thousand phloroglucinol derivatives have been characterized to date. As an example, 429 phloroglucinol derivatives have been isolated from the genus

alone [1]. Phloroglucinol derivatives found in plants and brown algae have extremely diverse structures, ranging from the simple grandinol, an acylphloroglucinol produced by several

species, to the more complex phlorotannins found in several families of brown algae [2][3]. These compounds often exhibit antiviral, antibacterial and antifungal activity [2]. Phloroglucinol derivatives are also produced by some microorganisms [2][4]. By contrast with the phloroglucinol derivatives found in plants and brown algae, phloroglucinol derivatives of microbial origin are rather simple. Some

strains produce 2,4-diacetylphlorglucinol (DAPG) alongside its biosynthetic intermediates monoacetylphloroglucinol (MAPG) and phloroglucinol.

DAPG-producing

spp. have received particular attention due to their ability to control numerous soil-borne plant diseases, including take-all of wheat, tobacco black root rot and sugar beet damping-off [4][5]. These bacteria also play an important role in natural disease suppressiveness found in several soils across the world. Besides their presence in the rhizosphere, DAPG-producing

spp. are also known to colonize various environment, including the phyllosphere [6], the skin surface of certain amphibians [7] and the surface of marine algae [8]. This review specifically covers rhizosphere-inhabiting DAPG-producing

spp.

Several reviews have been previously published on rhizosphere-inhabiting DAPG-producing

spp. and their role in take-all decline [4][9].

2. Genetics, Biochemistry, and Evolution of DAPG Biosynthesis

2.1. The Phl Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

Genes involved in DAPG biosynthesis were cloned several times from three different DAPG-producing

strains:

.

F113 [12] and

.

CHA0 [13]. Further characterization of the genomic fragment isolated from

sp. Q2-87 led to the description of the so-called

biosynthetic gene cluster (BCG) [14]. Six genes were originally described: four were found to be directly involved in DAPG biosynthesis (

) and the two others were shown to encode a putative permease (

) and a TetR regulatory protein (

). Three other genes were later discovered and associated with the BCG:

, which encodes a hydrolase involved in DAPG degradation [15],

, which encodes another TetR regulatory protein [15] and

, which encodes an uncharacterized protein [16][17]. The organization of the

BCG is conserved in all DAPG-producing

spp. sequenced to date [18]. The biosynthetic cluster and the current understanding of the DAPG biosynthesis pathway are presented in

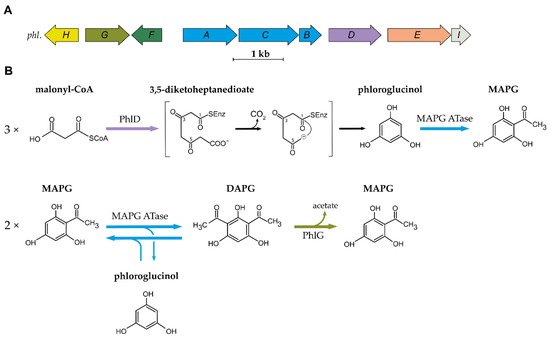

.

Organization of the 2,4-DAPG biosynthetic cluster and current understanding of the biosynthesis scheme. (

) Organization of the

biosynthetic gene cluster found in DAPG-producing

spp. (

) Current understanding of the biosynthesis and degradation of DAPG in the genus

. MAPG ATase is an enzyme multiplex composed of PhlA, PhlB and PhlC units. Abbreviations are as follows: MAPG, monoacetylphloroglucinol; DAPG, 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol.

2.2. Biosynthesis and Degradation of DAPG

The first step in the biosynthesis of DAPG is catalysed by the type III polyketide synthase (PKS) PhlD [14][19]. Type III PKSs are homodimeric enzymes that catalyse the iterative condensation of a starter substrate (usually an acyl-CoA) with several extender substrate units (usually malonyl-CoA) to generate a linear polyketide, which is subsequently cyclized [20]. Bangera and Thomashow [14] proposed that PhlD uses acetoacetyl-CoA as the starter substrate to produce monoacetylphloroglucinol (MAPG), but it was later showed that PhlD produces phloroglucinol from malonyl-CoA instead [19]. While PhlD uses malonyl-CoA as a preferred substrate, it also accepts other starter substrates with an aliphatic chain of C

-C

in vitro [21]. The proposed mechanism leading to the formation of phloroglucinol is that PhlD catalyses the iterative condensation of three molecules of malonyl-CoA into 3,5-diketoheptanedioate [19]. This polyketide intermediate undergoes decarboxylation and is subsequently cyclized via a Claisen condensation, leading to the formation of phloroglucinol [19][21].

In the following steps, acetylation of phloroglucinol leads to the formation of MAPG, which is subsequently acetylated into DAPG. MAPG was identified as a putative intermediate in DAPG biosynthesis by Shanahan and colleagues [22], who also found experimental evidence for an enzymatic acetyltransferase activity in cell-free extracts of

.

F113. Bangera and Thomashow [14] found that

was required for the biosynthesis of MAPG and DAPG, suggesting a role for PhlACB in the production and the acetylation of MAPG. Achkar and colleagues [19] confirmed that the product of

catalyses the acetylation of phloroglucinol and MAPG: The addition of phloroglucinol to the culture medium of an

.

strain carrying plasmid-localized

led to the formation of MAPG and DAPG. Later, Hayashi and colleagues [17] characterized the multimeric enzyme composed of PhlA, PhlC and PhlB units, which was named MAPG acetyltransferase (MAPG ATase). This enzyme, unlike most acetyltransferases described so far, was shown to catalyse C-C bond formation without the use of CoA-activated substrates [17]. The MAPG ATase catalyses the disproportionation of two molecules of MAPG, resulting in the formation of DAPG and the production of phloroglucinol.

The MAPG ATase also catalyses the reverse reaction, yielding two molecules of MAPG from a molecule of DAPG and a molecule of phloroglucinol [17]. This results in an equilibrium where DAPG, MAPG and phloroglucinol are present at quasi-equimolar concentration. Recent studies have provided new insight into the catalytic properties, the mechanism, and the structure of the MAPG ATase [23][24][25][26][27]. This enzyme was shown to use various non-natural substrates as acyl-donor in in vitro experiments [26][27][28]. This is particularly interesting given the fact that the acyl donor involved in MAPG biosynthesis from phloroglucinol remains to be characterized. The crystal structure revealed that PhlACB subunits are arranged in a Phl(A

C

)

B

composition where four PhlB units mediate the binding of two PhlA and two PhlC dimers [23]. Crystal soaking and site-directed mutagenesis experiments suggest that only PhlC units are involved in the acyl transfer reaction [23].

DAPG is degraded by the zinc-dependent hydrolase PhlG [29][30]. PhlG degrades DAPG into MAPG and acetate by cleaving one of the C-C bonds linking the acetyl groups to the phenolic ring [29][30]. This enzyme is highly specific for its substrate DAPG, as it is unable to degrade structurally similar compounds, such as MAPG or triacetylphloroglucinol [29]. The crystal structure of PhlG revealed that it cleaves C-C bonds using a Bet v1-like fold domain, contrary to the alpha/beta fold classically used by hydrolases [30].

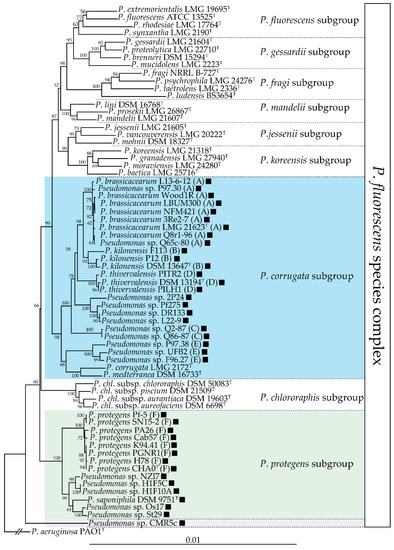

2.3. Distribution and Evolution of the Phl Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

The

BCG is mainly found in the

.

and

.

subgroups of the

.

species complex [18], as shown in

. The

BCG is not present in all the strains belonging to these two subgroups, and its distribution in these two subgroups is patchy [18][31][32].

Distribution of the

biosynthetic gene cluster in the

.

species complex. This neighbour-joining phylogeny is based on an alignment of the concatenated partial sequences of four housekeeping genes (16s rDNA,

,

,

; 2945 nucleotides total) generated using MUSCLE [33]. The phylogenetic tree was generated using PhyML [34] and the distance matrices were calculated by the Jukes-Cantor method. Bootstrap values over 50% (out of 1000 replicates) are indicated at the nodes. The presence of a black square indicates that that strain harbours the

biosynthetic gene cluster. The three subgroups encompassing DAPG-producing strains are highlighted in color. Letters following the strain names correspond to multilocus phylogenetic groups described by Frapolli and colleagues [35].

Almario and colleagues [18] proposed that the

cluster was acquired independently in these two groups and that this cluster was subsequently lost in some lineages of the

.

subgroup. A recent study reported that the

BCG is present in about half of the genomes sequenced from the

.

subgroup [32]. Interestingly, this subgroup includes numerous phytopathogenic strains, prominently strains belonging to the species

.

and

.

[36][37]. These phytopathogenic strains do not harbour the

BCG, suggesting that this cluster could have been lost during the transition between commensal and pathogenic lifestyles. The fact that DAPG can trigger induced systemic resistance in some plant species [38][39][40] is an undesirable trait for a plant pathogen, which means that it could have been counter-selected in these lineages. Outside of these two subgroups, the

BCG is also present in several other strains, both inside and outside of the

.

BCG has also been found outside of the

genus: the presence of the

BCG has been reported in three non-pathogenic

, namely

EGD-HP2,

MWU328 and

piscinae ND17 [18].

The origin of this cluster remains unclear. Most authors agreed upon the fact that the acquisition of the

BCG in the

.

species complex is an ancestral event [16][18][42]. The

BCG might have been acquired separately by the different groups of DAPG-producing

spp. [18]. In

sp. OT69, the

BCG is embedded in a putative genomic island, suggesting a more recent acquisition by this strain [18]. Kidarsa and colleagues [43] proposed that the

genes might have been acquired from an Archaea. Homologs of these three genes are present in a contiguous gene cluster and in the same order in multiple groups of Archaea, where they may play a role in fatty acid metabolism [43].

References

- Bridi, H.; de Carvalho Meirelles, G.; von Poser, G.L. Structural diversity and biological activities of phloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum species. Phytochemistry 2018, 155, 203–232.

- Singh, I.P.; Bharate, S.B. Phloroglucinol compounds of natural origin. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 558–591.

- Shrestha, S.; Zhang, W.; Smid, S. Phlorotannins: A review on biosynthesis, chemistry and bioactivity. Food Biosci. 2020, 100832.

- Weller, D.M.; Landa, B.; Mavrodi, O.; Schroeder, K.; De La Fuente, L.; Blouin Bankhead, S.; Allende Molar, R.; Bonsall, R.; Mavrodi, D.; Thomashow, L. Role of 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. in the defense of plant roots. Plant Biol. 2007, 9, 4–20.

- Weller, D.M. Pseudomonas biocontrol agents of soilborne pathogens: Looking back over 30 years. Phytopathology 2007, 97, 250–256.

- Müller, T.; Behrendt, U.; Ruppel, S.; von der Waydbrink, G.; Müller, M.E. Fluorescent pseudomonads in the phyllosphere of wheat: Potential antagonists against fungal phytopathogens. Curr. Microbiol. 2016, 72, 383–389.

- Myers, J.M.; Ramsey, J.P.; Blackman, A.L.; Nichols, A.E.; Minbiole, K.P.; Harris, R.N. Synergistic inhibition of the lethal fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis: The combined effect of symbiotic bacterial metabolites and antimicrobial peptides of the frog Rana muscosa. J. Chem. Ecol. 2012, 38, 958–965.

- Isnansetyo, A.; Cui, L.; Hiramatsu, K.; Kamei, Y. Antibacterial activity of 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol produced by Pseudomonas sp. AMSN isolated from a marine alga, against vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2003, 22, 545–547.

- Kwak, Y.-S.; Weller, D.M. Take-all of wheat and natural disease suppression: A review. Plant Pathol. J. 2013, 29, 125.

- Vincent, M.N.; Harrison, L.; Brackin, J.; Kovacevich, P.; Mukerji, P.; Weller, D.; Pierson, E. Genetic analysis of the antifungal activity of a soilborne Pseudomonas aureofaciens strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 2928–2934.

- Bangera, M.G.; Thomashow, L.S. Characterization of a genomic locus required for synthesis of the antibiotic 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol by the biological control agent Pseudomonas fluorescens Q2-87. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1996, 9, 83.

- Fenton, A.; Stephens, P.; Crowley, J.; O’callaghan, M.; O’gara, F. Exploitation of gene (s) involved in 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol biosynthesis to confer a new biocontrol capability to a Pseudomonas strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 3873–3878.

- Keel, C.; Schnider, U.; Maurhofer, M.; Voisard, C.; Laville, J.; Burger, U.; Wirthner, P.; Haas, D.; Défago, G. Suppression of Root Diseases by Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0: Importance of the Bacterial Secondary Metabolite 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1992, 5, 4–13.

- Bangera, M.G.; Thomashow, L.S. Identification and characterization of a gene cluster for synthesis of the polyketide antibiotic 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol from Pseudomonas fluorescens Q2-87. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 3155–3163.

- Schnider-Keel, U.; Seematter, A.; Maurhofer, M.; Blumer, C.; Duffy, B.; Gigot-Bonnefoy, C.; Reimmann, C.; Notz, R.; Défago, G.; Haas, D. Autoinduction of 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol biosynthesis in the biocontrol agent Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 and repression by the bacterial metabolites salicylate and pyoluteorin. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 1215–1225.

- Moynihan, J.A.; Morrissey, J.P.; Coppoolse, E.R.; Stiekema, W.J.; O’Gara, F.; Boyd, E.F. Evolutionary history of the phl gene cluster in the plant-associated bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 2122–2131.

- Hayashi, A.; Saitou, H.; Mori, T.; Matano, I.; Sugisaki, H.; Maruyama, K. Molecular and catalytic properties of monoacetylphloroglucinol acetyltransferase from Pseudomonas sp. YGJ3. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012, 76, 559–566.

- Almario, J.; Bruto, M.; Vacheron, J.; Prigent-Combaret, C.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; Muller, D. Distribution of 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol biosynthetic genes among the Pseudomonas spp. reveals unexpected polyphyletism. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1218.

- Achkar, J.; Xian, M.; Zhao, H.; Frost, J. Biosynthesis of phloroglucinol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5332–5333.

- Shimizu, Y.; Ogata, H.; Goto, S. Type III polyketide synthases: Functional classification and phylogenomics. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 50–65.

- Zha, W.; Rubin-Pitel, S.B.; Zhao, H. Characterization of the substrate specificity of PhlD, a type III polyketide synthase from Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 32036–32047.

- Shanahan, P.; Glennon, J.; Crowley, J.; Donnelly, D.; O’Gara, F. Liquid chromatographic assay of microbially derived phloroglucinol antibiotics for establishing the biosynthetic route to production, and the factors affecting their regulation. Anal. Chim. Acta 1993, 272, 271–277.

- Pavkov-Keller, T.; Schmidt, N.G.; Żądło-Dobrowolska, A.; Kroutil, W.; Gruber, K. Structure and catalytic mechanism of a bacterial Friedel–Crafts acylase. ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 88–95.

- Schmidt, N.G.; Żądło-Dobrowolska, A.; Ruppert, V.; Höflehner, C.; Wiltschi, B.; Kroutil, W. Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of acyltransferase from Pseudomonas protegens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 6057–6068.

- Sheng, X.; Kazemi, M.; Żądło-Dobrowolska, A.; Kroutil, W.; Himo, F. Mechanism of Biocatalytic Friedel–Crafts Acylation by Acyltransferase from Pseudomonas protegens. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 570–577.

- Schmidt, N.G.; Kroutil, W. Acyl donors and additives for the biocatalytic Friedel–Crafts acylation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 5865–5871.

- Żądło-Dobrowolska, A.; Schmidt, N.G.; Kroutil, W. Thioesters as Acyl Donors in Biocatalytic Friedel-Crafts-type Acylation Catalyzed by Acyltransferase from Pseudomonas protegens. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 1064–1068.

- Schmidt, N.G.; Pavkov-Keller, T.; Richter, N.; Wiltschi, B.; Gruber, K.; Kroutil, W. Biocatalytic Friedel–crafts acylation and fries reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7615–7619.

- Bottiglieri, M.; Keel, C. Characterization of PhlG, a hydrolase that specifically degrades the antifungal compound 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol in the biocontrol agent Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 418–427.

- He, Y.-X.; Huang, L.; Xue, Y.; Fei, X.; Teng, Y.-B.; Rubin-Pitel, S.B.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, C.-Z. Crystal structure and computational analyses provide insights into the catalytic mechanism of 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol hydrolase PhlG from Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 4603–4611.

- Garrido-Sanz, D.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M.; Martín, M.; Rivilla, R.; Redondo-Nieto, M. Genomic and Genetic Diversity within the Pseudomonas fluorescens Complex. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150183.

- Melnyk, R.A.; Hossain, S.S.; Haney, C.H. Convergent gain and loss of genomic islands drive lifestyle changes in plant-associated Pseudomonas. ISME J. 2019, 13, 1575–1588.

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797.

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.-F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321.

- Frapolli, M.; Défago, G.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y. Multilocus sequence analysis of biocontrol fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. producing the antifungal compound 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1939–1955.

- Catara, V.; Sutra, L.; Morineau, A.; Achouak, W.; Christen, R.; Gardan, L. Phenotypic and genomic evidence for the revision of Pseudomonas corrugata and proposal of Pseudomonas mediterranea sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 1749–1758.

- Trantas, E.A.; Licciardello, G.; Almeida, N.F.; Witek, K.; Strano, C.P.; Duxbury, Z.; Ververidis, F.; Goumas, D.E.; Jones, J.D.; Guttman, D.S. Comparative genomic analysis of multiple strains of two unusual plant pathogens: Pseudomonas corrugata and Pseudomonas mediterranea. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 811.

- Iavicoli, A.; Boutet, E.; Buchala, A.; Métraux, J.-P. Induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana in response to root inoculation with Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2003, 16, 851–858.

- Weller, D.M.; Mavrodi, D.V.; van Pelt, J.A.; Pieterse, C.M.; van Loon, L.C.; Bakker, P.A. Induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato by 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens. Phytopathology 2012, 102, 403–412.

- Chae, D.-H.; Kim, D.-R.; Cheong, M.S.; Lee, Y.B.; Kwak, Y.-S. Investigating the induced systemic resistance mechanism of 2, 4-Diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG) using DAPG hydrolase-transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Pathol. J. 2020, 36, 255.

- Biessy, A.; Novinscak, A.; Blom, J.; Léger, G.; Thomashow, L.S.; Cazorla, F.M.; Josic, D.; Filion, M. Diversity of phytobeneficial traits revealed by whole-genome analysis of worldwide-isolated phenazine-producing Pseudomonas spp. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 437–455.

- Frapolli, M.; Pothier, J.F.; Défago, G.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y. Evolutionary history of synthesis pathway genes for phloroglucinol and cyanide antimicrobials in plant-associated fluorescent pseudomonads. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2012, 63, 877–890.

- Kidarsa, T.A.; Goebel, N.C.; Zabriskie, T.M.; Loper, J.E. Phloroglucinol mediates cross-talk between the pyoluteorin and 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol biosynthetic pathways in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 81, 395–414.