Farmers markets are regular, recurring gatherings at a common facility or area where farmers and ranchers directly sell a variety of fresh fruits, vegetables, and other locally grown farm products to consumers. Markets rebuild and maintain local and regional food systems, leading to an outsized impact on the food system relative to their share of produce sales. Previous research has demonstrated the multifaceted impacts that farmers markets have on the communities, particularly economically. Recent scholarship in the United States has expanded inquiry into social impacts that markets have on communities, including improving access to fresh food products and increasing awareness of the sustainable agricultural practices adopted by producers, as well developing tools for producers and market stakeholders to measure their impact on both producers and communities.

1. Introduction

Farmers markets are regular or seasonal community gatherings where local farmers, ranchers, fishers, harvesters, food vendors, and artisans can sell their local and sustainably products directly to community members [1][2][3]. Since the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) began recording the number of farmers markets in 1994, the prevalence has increased from 1755 to 8761 in 2019 [4]. According to the 2015 Local Food Marketing Practices Survey, farmers market sales consisted of 23% of direct-to-consumer farm sales, totaling $711 million in revenue (USDA 2015). This growth may be attributed to grassroots promotion of farmers markets at the local level converging with an increase in the number of small farms and consumer interest and demand for fresh, high quality local foods [5][6]. Customers are also drawn to farmers markets for access to healthy food, social appeal, convenience, and atmosphere [7][8][9][10][11][12][13]. Farmers markets can contribute benefits towards public health, economic well-being, social engagement, and ecological concerns [14][15].

Farmers markets are regular or seasonal community gatherings where local farmers, ranchers, fishers, harvesters, food vendors, and artisans can sell their local and sustainably products directly to community members [1,2,3]. Since the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) began recording the number of farmers markets in 1994, the prevalence has increased from 1755 to 8761 in 2019 [4]. According to the 2015 Local Food Marketing Practices Survey, farmers market sales consisted of 23% of direct-to-consumer farm sales, totaling $711 million in revenue (USDA 2015). This growth may be attributed to grassroots promotion of farmers markets at the local level converging with an increase in the number of small farms and consumer interest and demand for fresh, high quality local foods [5,6]. Customers are also drawn to farmers markets for access to healthy food, social appeal, convenience, and atmosphere [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Farmers markets can contribute benefits towards public health, economic well-being, social engagement, and ecological concerns [14,15].

The current iteration of United States farmers markets developed in the 1970s and evolved as it built organizational and structural elements and created principles for successful markets [1][16]. In response to grassroots pressure, federal initiatives such as the Farmer-to-Consumer Direct Marketing Act of 1976 and the Farmers Market Promotion Program of the 2002 Farm Bill developed and played significant roles in fostering the growth and development of farmers markets [17][18]. At the state and local levels, municipalities, main street organizations, and nonprofits embrace markets as economic and equity development strategies [19]. Federal and nonprofit food assistance programs may use farmers markets to increase access to fresh produce for individuals in underserved neighborhoods [20].

The current iteration of United States farmers markets developed in the 1970s and evolved as it built organizational and structural elements and created principles for successful markets [1,16]. In response to grassroots pressure, federal initiatives such as the Farmer-to-Consumer Direct Marketing Act of 1976 and the Farmers Market Promotion Program of the 2002 Farm Bill developed and played significant roles in fostering the growth and development of farmers markets [17,18]. At the state and local levels, municipalities, main street organizations, and nonprofits embrace markets as economic and equity development strategies [19]. Federal and nonprofit food assistance programs may use farmers markets to increase access to fresh produce for individuals in underserved neighborhoods [20].

Due to their direct connection to both producers and end-users of food products, farmers markets contain multiple leverage points to improve health and ecological outcomes of the food system [2]. In 2008, Brown and Miller summarized the documented impacts of farmers markets on their local communities, finding that farmers markets generate significant economic benefits for both local economies and farmers [2]. In the following decade, the number of farmers markets in the US has grown by an additional 86%. The continued rapid growth of farmers markets has resulted in a significant expansion of the literature investigating the structure and impact of local markets throughout the supply chain, including lines of inquiry not explored in 2008. In particular, there has been increased attention to the role of farmers markets in contributing to a socially and ecologically sustainable food system, as well as the potential and limitations of utilizing farmers markets to contribute to food security and justice efforts across the US. In addition, partnerships between academia and organizations supporting farmers markets have stimulated the development of new tools to allow markets to engage in “citizen science” to track and communicate the impact of their markets on local communities.

2. Organizational Structure of Farmers Markets

A given market’s structure is determined by both its social mission and its organizational characteristics, such as size, business model, governance capacity, and available resources [21][22]. Most farmers markets are managed by a paid or volunteer market manager who runs day-to-day operations, as well as a governing body, such as a board of directors, that develops a mission statement, business plan, and by-laws [21][23][24][25]. Market operators create the market layout, manage staffing needs, formulate and enforce market policies, and ensure adequate and representative governance [22][26]. Understanding, navigating, and communicating relevant federal, state, and local policies to producers are all de facto parts of most market managers’ responsibilities. Governance also includes facilitating a board of directors or an advisory committee to ensure representation of all relevant stakeholder groups (such as farmers, shoppers, allied governmental and nongovernmental organizations) and development of appropriate market policies [26].

A given market’s structure is determined by both its social mission and its organizational characteristics, such as size, business model, governance capacity, and available resources [21,22]. Most farmers markets are managed by a paid or volunteer market manager who runs day-to-day operations, as well as a governing body, such as a board of directors, that develops a mission statement, business plan, and by-laws [21,23,24,25]. Market operators create the market layout, manage staffing needs, formulate and enforce market policies, and ensure adequate and representative governance [22,26]. Understanding, navigating, and communicating relevant federal, state, and local policies to producers are all de facto parts of most market managers’ responsibilities. Governance also includes facilitating a board of directors or an advisory committee to ensure representation of all relevant stakeholder groups (such as farmers, shoppers, allied governmental and nongovernmental organizations) and development of appropriate market policies [26].

Federal, state, and local agencies regulate farmers market business activities, some of which address public health and safety. Federal agencies (e.g., USDA and the Food and Drug Administration) may assign some food safety requirements pertaining to the production, harvest, post-harvest handling, and marketing of foods, as well as tax and labor laws pertaining both to farm businesses and farmers market organizations. State and local regulations vary by community and address some or all of the following: licensing, permits, collection and reporting of sales tax, labeling laws, food handling and preparation, food microbiological and chemical safety, labor issues, and farming practices. Often local regulations supersede state and federal regulations and therefore need to be considered during the creation of local farmers market regulations to avoid confusion or potentially contradictory or miscommunicated expectations [27]. A growing number of states, however, are attempting to simplify and streamline the duplicative or contradictory processes by which farmers sell and offer samples of their products at markets [28]. As markets grow in number, size, and product diversity, they must learn to interact comfortably with the plethora of official imperatives, restrictions, and fees that connect them to social, political, and economic systems.

Organizational structure, goals, zoning regulations, nearby land uses, proximity to other markets, and simple availability of space can influence where farmers markets are located as well as their dates of operation. Seasonal farmers markets often require minimal physical facilities. According to the 2019 Farmers Market Manager Survey (FMMS), 21% of markets operated year-round, and 36% utilized temporary facilities in their operations. Set up of temporary facilities is relatively quick, inexpensive, and flexible, relying mostly on energy and muscle as opposed to brick and mortar. This flexibility helps markets in both rural and urban areas to provide access to healthy and affordable foods close to the neighborhoods where customers live [29][30][31]. Markets are also flexible in their ability to open in different areas on different days; while the 2019 FMMS indicates that a majority of markets operate on Saturday, at least 10% of markets surveyed nationally operate on each day of the week with the exception of Monday. In areas with a high density of farmers markets, this provides households with multiple opportunities to buy local food products during a typical week.

Organizational structure, goals, zoning regulations, nearby land uses, proximity to other markets, and simple availability of space can influence where farmers markets are located as well as their dates of operation. Seasonal farmers markets often require minimal physical facilities. According to the 2019 Farmers Market Manager Survey (FMMS), 21% of markets operated year-round, and 36% utilized temporary facilities in their operations. Set up of temporary facilities is relatively quick, inexpensive, and flexible, relying mostly on energy and muscle as opposed to brick and mortar. This flexibility helps markets in both rural and urban areas to provide access to healthy and affordable foods close to the neighborhoods where customers live [29,30,31]. Markets are also flexible in their ability to open in different areas on different days; while the 2019 FMMS indicates that a majority of markets operate on Saturday, at least 10% of markets surveyed nationally operate on each day of the week with the exception of Monday. In areas with a high density of farmers markets, this provides households with multiple opportunities to buy local food products during a typical week.

Zoning ordinances can establish community areas for farmers markets, modify permit requirements, and protect existing markets from re-development. Well-conceived farmers market zoning ordinances aim to locate markets on properties that have stable tenure and are accessible to prospective patrons, while also fostering community development by expanding access to fresh produce or bringing foot traffic to a neglected commercial district. Such policies encourage partnerships between farmers markets and communities, schools, local commerce or business organizations, hospitals, universities, and faith-based organizations [32]. Sometimes zoning ordinances even require farmers markets to accept food assistance benefits. For example, San Francisco’s city code was amended in 2009 to require farmers markets operating within the city to accept various forms of food assistance, including SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) benefits via Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) [33].

Common business models include independent nonprofits, private for-profits, private social enterprises with unofficial agreements among producers, public services sponsored by city or county governments, and even programs under the umbrella of existing agencies or organizations [22][25]. Many farmers markets operate under the umbrella of another organization and therefore are not recognized by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Incorporation of markets as nonprofit organizations by registering them with a state government as opposed to applying for tax-exempt status with the IRS has become increasingly common due to the legal challenges involved in filing IRS 501(c)(3) documentation; as of 2019, over 65% of farmers markets were registered as a nonprofit (USDA 2019). Despite difficulties, obtaining 501(c)(3) status from the IRS may help communicate a market’s commitment to a broad social agenda due to the high transparency required by the IRS for federally incorporated nonprofits [23]. Federally recognized tax-exempt status exempts a market from federal, state, and often local taxes, and the 501(c)(3) statute allows them to accept tax-deductible donations and become eligible for a wider variety of private and government grant programs. Nonprofit status can help farmers markets attract local private and public partners who can help pay for start-up costs with financial contributions or in-kind donations. Beyond funding, these partnerships also serve to embed markets within the social fabric of their communities, enabling the pursuit of various social and economic objectives [34].

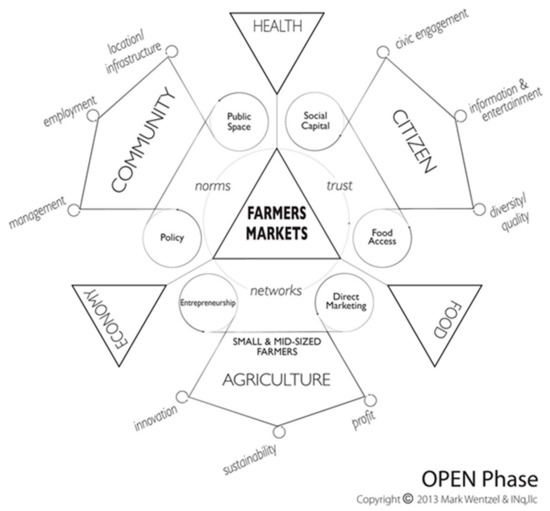

Common business models include independent nonprofits, private for-profits, private social enterprises with unofficial agreements among producers, public services sponsored by city or county governments, and even programs under the umbrella of existing agencies or organizations [22,25]. Many farmers markets operate under the umbrella of another organization and therefore are not recognized by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Incorporation of markets as nonprofit organizations by registering them with a state government as opposed to applying for tax-exempt status with the IRS has become increasingly common due to the legal challenges involved in filing IRS 501(c)(3) documentation; as of 2019, over 65% of farmers markets were registered as a nonprofit (USDA 2019). Despite difficulties, obtaining 501(c)(3) status from the IRS may help communicate a market’s commitment to a broad social agenda due to the high transparency required by the IRS for federally incorporated nonprofits [23]. Federally recognized tax-exempt status exempts a market from federal, state, and often local taxes, and the 501(c)(3) statute allows them to accept tax-deductible donations and become eligible for a wider variety of private and government grant programs. Nonprofit status can help farmers markets attract local private and public partners who can help pay for start-up costs with financial contributions or in-kind donations. Beyond funding, these partnerships also serve to embed markets within the social fabric of their communities, enabling the pursuit of various social and economic objectives [34]. illustrates the avenues of community impact frequently pursued by local markets and their synergies across actors.

Figure 1.

This framework illustrates the synergies created by farmers markets to benefit communities, individual citizens, and the farming community.

To attain financial sustainability, farmers markets must avoid dependence on grant support and be able to pay operational costs solely out of income derived from vendor fees and other market income. However, other markets, especially those whose primary purpose is to serve low-income or rural communities, may require outside funding for ongoing management and community outreach [35][36]. Over the last two decades, funding opportunities have expanded both in the diversity of funders and the total dollars available for market support, including grassroots neighborhood support, marketing assistance from agricultural extension services, in-store and online promotion by neighboring businesses, and federal funding. One prominent example is the growth of the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service’s Farmers Market Promotion Program (FMPP) [37]. The FMPP was originally created in 2006, and over the last decade has expanded the total funding made available from $1M in 2006 to $15M in 2016 [38]. FMPP funds can be used to support a wide swath of functions for farmers markets, including training, community outreach, marketing, and purchase and operations of Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) machines.

To attain financial sustainability, farmers markets must avoid dependence on grant support and be able to pay operational costs solely out of income derived from vendor fees and other market income. However, other markets, especially those whose primary purpose is to serve low-income or rural communities, may require outside funding for ongoing management and community outreach [35,36]. Over the last two decades, funding opportunities have expanded both in the diversity of funders and the total dollars available for market support, including grassroots neighborhood support, marketing assistance from agricultural extension services, in-store and online promotion by neighboring businesses, and federal funding. One prominent example is the growth of the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service’s Farmers Market Promotion Program (FMPP) [37]. The FMPP was originally created in 2006, and over the last decade has expanded the total funding made available from $1M in 2006 to $15M in 2016 [38]. FMPP funds can be used to support a wide swath of functions for farmers markets, including training, community outreach, marketing, and purchase and operations of Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) machines.

In addition to these forms of direct financial support, farmers markets are increasingly receiving indirect support from federal and state programs, such as the USDA Food and Nutrition Service’s (FNS) Farmers Market Nutrition Program (FMNP) for participants in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and for low-income seniors (SFMNP). These programs bring business to markets by distributing vouchers to eligible low-income families and seniors that can only be redeemed at farmers markets. Other programs, such as Double Up Food Bucks and equivalent programs developed by non-profits such as the Wholesome Wave Foundation and the Fair Food Network work to increase the value of food assistance dollars by using matching funds from donors, programs inspired in part due to effort by the former First Lady Michelle Obama [39][40].

In addition to these forms of direct financial support, farmers markets are increasingly receiving indirect support from federal and state programs, such as the USDA Food and Nutrition Service’s (FNS) Farmers Market Nutrition Program (FMNP) for participants in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and for low-income seniors (SFMNP). These programs bring business to markets by distributing vouchers to eligible low-income families and seniors that can only be redeemed at farmers markets. Other programs, such as Double Up Food Bucks and equivalent programs developed by non-profits such as the Wholesome Wave Foundation and the Fair Food Network work to increase the value of food assistance dollars by using matching funds from donors, programs inspired in part due to effort by the former First Lady Michelle Obama [39,40].

3. Evaluating the Impact of Farmers Markets

A rapidly expanding segment of the literature on farmers markets explores the theoretical and methodological approaches to characterizing their impact on communities and farmers. As Brown and Miller note, this push towards evaluating the impact of farmers markets is attributed to the development of the rapid market assessment by Lev, Stephenson, and Brewer in 2007, with a primary focus at the time on assessing the economic impact generated by farmers markets. The 2006 Farmers Market Manager Survey did not feature a question measuring the adoption of assessment techniques by markets. In 2019, the Market Manager Survey included both questions, asking whether markets had conducted an assessment of their operations, as well as the type of assessment conducted. They found that 25.1% of survey markets had conducted an evaluation in the last year, encompassing a wide spectrum of objectives, including customer counts and product preferences, vendor needs, and sales information from producers [41], reflecting the growing diversity of methods and lines of inquiry among scholars. Given the multiple avenues by which markets can affect local food systems, there has been a growing recognition among researchers that maximizing their benefits requires a simultaneous effort to increase the frequency, location, and product diversity at markets, concurrent with an appropriate balance of patronage and supply. Focusing on single dimensions of market performance, such as the overall sales of the market, will not allow markets to realize their full potential to improve public health and community well-being at multiple scales and in multiple dimensions. Single focus or myopia can hinder the ability of markets to reach their full potential to positively impact community development and public health. For example, evaluating changes in fruit and vegetable access or intake as a result of targeted nutrition education interventions at markets is only one of many potential measures of the public health benefits [42], when market location and access to adequate transportation, among other factors, also influence the purchase of fresh produce at markets.

A rapidly expanding segment of the literature on farmers markets explores the theoretical and methodological approaches to characterizing their impact on communities and farmers. As Brown and Miller note, this push towards evaluating the impact of farmers markets is attributed to the development of the rapid market assessment by Lev, Stephenson, and Brewer in 2007, with a primary focus at the time on assessing the economic impact generated by farmers markets. The 2006 Farmers Market Manager Survey did not feature a question measuring the adoption of assessment techniques by markets. In 2019, the Market Manager Survey included both questions, asking whether markets had conducted an assessment of their operations, as well as the type of assessment conducted. They found that 25.1% of survey markets had conducted an evaluation in the last year, encompassing a wide spectrum of objectives, including customer counts and product preferences, vendor needs, and sales information from producers [144], reflecting the growing diversity of methods and lines of inquiry among scholars. Given the multiple avenues by which markets can affect local food systems, there has been a growing recognition among researchers that maximizing their benefits requires a simultaneous effort to increase the frequency, location, and product diversity at markets, concurrent with an appropriate balance of patronage and supply. Focusing on single dimensions of market performance, such as the overall sales of the market, will not allow markets to realize their full potential to improve public health and community well-being at multiple scales and in multiple dimensions. Single focus or myopia can hinder the ability of markets to reach their full potential to positively impact community development and public health. For example, evaluating changes in fruit and vegetable access or intake as a result of targeted nutrition education interventions at markets is only one of many potential measures of the public health benefits [145], when market location and access to adequate transportation, among other factors, also influence the purchase of fresh produce at markets.

As a result, realizing the potential of farmers markets requires the use of transdisciplinary, trans-sector, and multilevel engagement of citizen, community, and agricultural stakeholders within the highly interconnected food, economic, and health systems () [43][44]. Assessing the impact of these interventions requires implementing a consistent data collection approach, which can be challenging for market managers, who are tasked with many different responsibilities, often with minimal budgets [45]. Several data collection tools have become available in the last decade to meet this need. For instance, Farm2Facts, a data collection tool developed and housed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is a citizen-science tool that enables individual markets to track and report their impact in the community through existing sources of potential secondary data such as vendor applications as well as simple primary data collection through customer and producer surveys [46][47][48]. This includes economic impact (e.g., the number of customers at the market and how much they spend at the market and at local businesses), social impact (e.g., food assistance spending, percentage of visitors who bike to the market), and is expanding its range of metrics to characterize ecological impact, though it currently tracks distance traveled by producers to the market. Another data collection tool to assist farmer market managers in tracking their impact is Farmers Market Metrics, developed by the Farmers Market Coalition, which offers a similar profile of metric collection and reporting. Placing farmers markets within the larger context of food, economic, and health systems can help planners, organizers, researchers, policy makers, and other farmers market stakeholders more effectively target potential points of intervention and anticipate the myriad consequences flowing from the complex social and cultural phenomenon that is the farmers market world [43][44].

) [146,147]. Assessing the impact of these interventions requires implementing a consistent data collection approach, which can be challenging for market managers, who are tasked with many different responsibilities, often with minimal budgets [148]. Several data collection tools have become available in the last decade to meet this need. For instance, Farm2Facts, a data collection tool developed and housed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is a citizen-science tool that enables individual markets to track and report their impact in the community through existing sources of potential secondary data such as vendor applications as well as simple primary data collection through customer and producer surveys [149,150,151]. This includes economic impact (e.g., the number of customers at the market and how much they spend at the market and at local businesses), social impact (e.g., food assistance spending, percentage of visitors who bike to the market), and is expanding its range of metrics to characterize ecological impact, though it currently tracks distance traveled by producers to the market. Another data collection tool to assist farmer market managers in tracking their impact is Farmers Market Metrics, developed by the Farmers Market Coalition, which offers a similar profile of metric collection and reporting. Placing farmers markets within the larger context of food, economic, and health systems can help planners, organizers, researchers, policy makers, and other farmers market stakeholders more effectively target potential points of intervention and anticipate the myriad consequences flowing from the complex social and cultural phenomenon that is the farmers market world [146,147].