Human mitochondrial pyruvate carriers (hMPCs), which are required for the uptake of pyruvate into mitochondria, are associated with several metabolic diseases, including type 2 diabetes and various cancers. Yeast MPC was recently demonstrated to form a functional unit of heterodimers. However, human MPC-1 (hMPC-1) and MPC-2 (hMPC-2) have not yet been individually isolated for their detailed characterization, in particular in terms of their structural and functional properties, namely, whether they exist as homo- or heterodimers. In this study, hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 were successfully isolated in micelles and they formed stable homodimers. However, the heterodimer state was found to be dominant when both hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 were present. In addition, as heterodimers, the molecules exhibited a higher binding capacity to both substrates and inhibitors, together with a larger structural stability than when they existed as homodimers. Taken together, our results demonstrated that the hetero-dimerization of hMPCs is the main functional unit of the pyruvate metabolism, providing a structural insight into the transport mechanisms of hMPCs.

- human mitochondrial pyruvate carrier

- hetero-complex

- cellular homeostasis

- oligomerization

1. Introduction

As the final product of glycolysis, pyruvate is essential for numerous aspects of the human metabolism [1]. It is necessary for the generation of ATP and drives several major biosynthetic pathways in mitochondria [1]. Many studies of the pyruvate metabolism have evaluated the correlations between diseases and pyruvate flow [1][2][3][4]. The pyruvate branch point, which controls the flow of pyruvate between oxidative and fermentative routes, is central to cellular homeostasis. Although the transport of pyruvate into mitochondria has been studied for decades [5][6], mitochondrial pyruvate carriers (MPCs), which play key roles in pyruvate uptake, have been discovered only recently [7][8]. MPCs regulate the uptake of pyruvate from the mitochondrial intermembrane space into the mitochondrial matrix, the dysfunction of which can lead to the development of metabolic diseases [9]. The discovery of MPCs has led to a number of molecular genetic studies, including those on numerous cellular processes controlled by pyruvate uptake.

Human MPCs (hMPCs) include two protomers, hMPC-1 and hMPC-2, which are essential for pyruvate transport [2][7]. However, the homo- and heterotypic assembly and stoichiometry of the two protomers is not yet fully understood [1][10]. Very recently, structural analyses demonstrated that the functional units of yeast MPC are heterodimers [11]. In a previous study, hMPCs were co-expressed and purified using a yeast expression system, and although no substantial complex formation was observed, the individual function of hMPC-2 as an autonomous pyruvate transporter was demonstrated [12]. Subsequently, the molecular characterization of the homo- and heterotypic assemblies of hMPCs in vitro is necessary to improve our understanding of these molecules.

Recently, several studies on MPCs have focused on the individual activities of homotypic as well as heterotypic MPCs. As a result, the downregulation or deletion of MPC-1 was found to be associated with various types of cancer, while MPC-2 was found to play an important role in the control of hepatic gluconeogenesis [13][14][15]. Thus, the different expression levels and activities of individual MPCs and the ratio of heterotypic MPC formation are associated with differences in cellular metabolism. Moreover, the dysfunction of MPCs has been associated with various diseases, including cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and type 2 diabetes, caused by abnormal metabolic activities. As a result, MPCs represent a potential target molecule for the development of therapeutic drugs [16][17][18][19][20].

Several compounds have been shown to inhibit MPC activity [21][22][23][24]. For example, thiazolidinediones (TZD), a group of oral anti-diabetic drugs, act as ligands for PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma) [3][25][26] and inhibit MPC activity at clinically relevant concentrations [27]. α-cyano-β-(1-phenylindol-3-yl)-acrylate (UK5099), an efficient blocker of MPC, inhibits pyruvate-dependent oxygen consumption and pyruvate mitochondrial transportation in vitro [2][22][28].

2. Expression and Purification of hMPCs

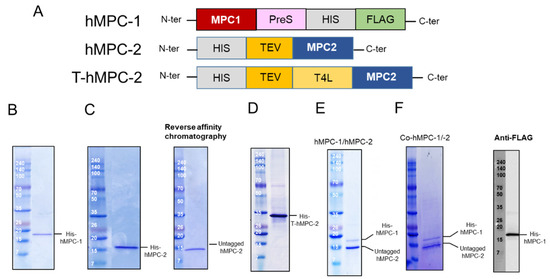

Although MPC-1 and MPC-2 are generally considered to form heterotypic complexes, there is little structural evidence to support this in vitro [4,10]. hMPCs were recently characterized in vitro, however, more information about their formation of heterotypic complexes is needed, since previous studies have mainly focused on the homotypic complex of hMPC-2, rather than its formation of a heterotypic complex with hMPC-1 [12]. In the case of hMPC-1, the N-terminal tags, including the 10× His-tag, FLAG tag, and PreScission enzyme recognition sequence, were moved to the C-terminal region for protein expression (Although MPC-1 and MPC-2 are generally considered to form heterotypic complexes, there is little structural evidence to support this in vitro [4][10]. hMPCs were recently characterized in vitro, however, more information about their formation of heterotypic complexes is needed, since previous studies have mainly focused on the homotypic complex of hMPC-2, rather than its formation of a heterotypic complex with hMPC-1 [12]. In the case of hMPC-1, the N-terminal tags, including the 10× His-tag, FLAG tag, and PreScission enzyme recognition sequence, were moved to the C-terminal region for protein expression (

Figure 1A). None of the hMPC-1 constructs containing N-terminal tags expressed well. To determine the structural and biochemical properties of the heterotypic complex of hMPCs in vitro, two constructs of hMPC-2 were designed and evaluated for their size distribution using size-exclusion gel chromatography (SEC). The first, labeled hMPC-2, contained an influenza hemagglutinin (HA) tag, 10× His-tag, and Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) cleavage sequence at the N-terminus. The other, labeled T-hMPC-2, contained an additional T4 Lysozyme (T4L) sequence after the 10× His-tag (

Figure 1A). A modified pFastBac vector comprised of a polyhedrin (PH) promoter and a HA tag was used for all of the constructs to increase expression on the membrane [29,30].A). A modified pFastBac vector comprised of a polyhedrin (PH) promoter and a HA tag was used for all of the constructs to increase expression on the membrane [29][30].

Construct design and purification of human mitochondrial pyruvate carriers (hMPCs). (

) Schematic diagram of designed hMPC constructs. (

–

) Purification profiles of (

) His-hMPC-1, (

) His-hMPC-2 (left) and untagged hMPC-2 (right), and (

) His-T-hMPC-2. The N-terminal tags were removed from hMPC-2 by Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV). Un-tagged hMPC-2 (14.3 kDa) was isolated after reversed affinity column. The recombinant proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining in SDS-PAGE after metal affinity purification. (

) His-hMPC-1 (15.9 kDa) and untagged hMPC-2 (14.3 kDa) after the FLAG-resin column was co-eluted and confirmed by SDS-PAGE. (

) The co-expressed proteins, co-hMPC-1/-2, were confirmed by Coomassie blue staining in SDS-PAGE after purification. After TEV cleavage reaction, His-hMPC-1 and untagged hMPC-2 was co-eluted in the FLAG-resin column. hMPC-1 was confirmed by anti-FLAG-tag immunoblot analysis.

Three constructs, hMPC-1, hMPC-2, and T-hMPC-2, were successfully purified using a TALON affinity column in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% (

w/

v) DDM with 500 mM imidazole (

Figure 1B–D). The purified hMPC-1, hMPC-2, and T-hMPC-2 showed a single protein band at the expected molecular weight in SDS-PAGE analysis. For hMPC-2, the sample was treated with TEV enzyme for tag cleavage, after which the untagged protein was isolated using reversed affinity column (

Figure 1C). For the hMPC-1/hMPC-2 complex sample, C-terminal tagged hMPC-1 and untagged hMPC-2 were used. After mixing hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 at a 1:1 molar ratio, FLAG-resin column work were performed. hMPC-2 was found to co-elute with hMPC-1, indicating that they interacted to form a stable complex (

Figure 1E).

hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 (co-hMPC-1/-2) were co-expressed using a co-infection method in Sf9 cells, the co-eluted MPCs was confirmed after purification using both Ni-NTA and FLAG affinity column works (

Figure 1F). In our result, since the intensities of the purified hMPC-1 was relatively weaker than those of the purified hMPC-2, we verified the hMPC-1 band using a FLAG-antibody, which does not exist in hMPC-2 (

Figure 1F).

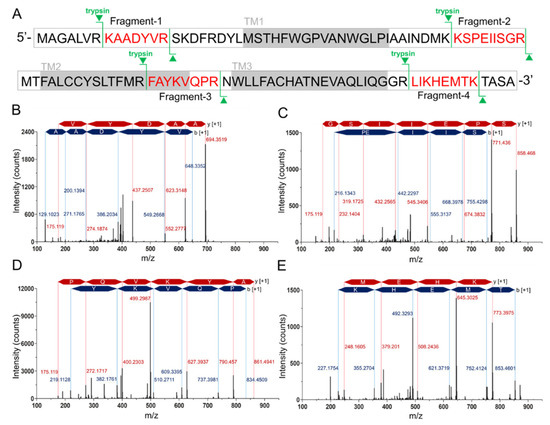

Since the difficulty of the protein expression and the similar molecular weight of hMPC-1 than hMPC-2, we further analyzed hMPC-1 through the liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (

Figure 2). In the tryptic peptide mapping, four trypsin digested peptide fragments such as KAADYVR (

Figure 2B), KSPEIISGR (

Figure 2C), FAYKVQPR (

Figure 2D), and LIKHEMTK (

Figure 2E) were seen. Sequence coverage is around 25% due to the limitation of the cleavage site of the trypsin. The purity of the protein was over 95% and no further peptide derived from other impurities identified. Non-specific glycosylation modification often occurs during protein expression in sf9 cells, which may affect the function of the target protein. In our experiments, there was no evidence of the glycosylation modification in the purified hMPCs from sf9 cell.

Tryptic peptide mapping of purified hMPC-1 by nano-LC-LTQ-Orbitrap-MS spectrum. (

) Sequence coverage of identified tryptic peptide fragments of hMPC-1. The peptide fragments identified in the LC-LTQ mass spectrum are highlighted in red. The trypsin digestion sites are marked in green lines. Gray boxes denote the transmembrane region. (

) The nano-LC-LTQ-Orbitrap-MS spectrum of tryptic peptide hMPC-1 fragments. The identified tryptic fragments sequence was as follows: (

) KAADYVR, (

) KSPEIISGR, (

) FAYKVQPR, and (

) LIKHEMTK. The peaks of the b-ion and y-ion are marked in blue and red together with identified amino acid sequences. The m/z of the identified peaks is labeled with blue and red characters.

The final yields of hMPC-1, hMPC-2, and T-hMPC-2 were approximately 0.9 mg, 0.8 mg, and 1.25 mg per liter, respectively. These results demonstrate the successful expression and purification of hMPCs on a large scale. These samples were then used for further characterization in vitro.

3. Discussion

Recently, evidence has suggested that MPCs are good therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases, including Parkinson’s disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes [18,19,31,32]. Moreover, the expression levels of MPC1 and MPC2 differ in various diseases, and the reduced expression of the MPC hetero-complex is associated with unfavorable clinicopathological characteristics [33]. The elucidation of the formation and properties of hetero- or homo-complex structures are very important owing to their direct links to functional and pathological features [33,34]. However, the composition of MPC complexes, oligomer states, and stoichiometry remain a topic of controversy. Despite the whole-body metabolic homeostasis of MPC and its important role in disease, little is known about the relationship between its function and structural conformation.Recently, evidence has suggested that MPCs are good therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases, including Parkinson’s disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes [18][19][31][32]. Moreover, the expression levels of MPC1 and MPC2 differ in various diseases, and the reduced expression of the MPC hetero-complex is associated with unfavorable clinicopathological characteristics [33]. The elucidation of the formation and properties of hetero- or homo-complex structures are very important owing to their direct links to functional and pathological features [33][34]. However, the composition of MPC complexes, oligomer states, and stoichiometry remain a topic of controversy. Despite the whole-body metabolic homeostasis of MPC and its important role in disease, little is known about the relationship between its function and structural conformation.

In this study, the large-scale purification of both hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 was performed for the first time using insect cells. Interestingly, although the same strategy was applied to hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 for high expression, their behaviors were markedly different. hMPC-1 with N-terminal tags was not well expressed, whereas hMPC-2 with N-terminal tags was expressed well in

Sf9. This suggests that the orientation during membrane anchoring differs [4]. Our model structures of hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 also suggest that they preferentially form a hetero-complex with reverse topology [4,35]. Very recently, hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 were co-expressed and purified in yeast; however, reliable homo- and hetero-complexes were not comprehensively characterized owing to the fact that a co-expression system was studied, rather than individual expression systems [12]. Thus, an advantage of our approach is that hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 were expressed and purified using both single and co-expression systems, with the flexibility to perform accurate comparisons in each experiment. Our results indicated that hMPC-1 is thermodynamically more stable than hMPC-2 and is the main determinant of the formation of hetero-complexes. These results support those reported in previous studies wherein hMPC-1 was found to be a key molecule in mitochondrial respiration, energy generation, various cancers, and type 2 diabetic kidney disease; despite this, hMPC-2 is also important [12,13,36,37,38]. In several studies, both the homo- and heterodimers of hMPCs have been proposed as functional units [11,12]. Our results suggest that the heterodimeric state is the more stable conformation, with higher binding affinities to ligands compared with the homodimeric state. Interestingly, the homo-complexes of hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 showed different stabilities and it may be related to their function. In the pyruvate-transport mechanism of hMPC-1 and hMPC-2, the hetero-complex is still considered the main conformation in vivo. Inhibitors were selected according to their ability to block pyruvate uptake in vivo, in which hMPCs exist as a hetero-complex. Our study of the interaction between hMPCs and various ligands demonstrated that the heterodimeric state had a stronger binding affinity than those of the homodimeric states of hMPCs. Even if the binding affinity did not directly represent the pyruvate uptake ability, it was indicative of the transport energy barrier under the same conditions. For this reason, we hypothesized that it is significantly easier to transport pyruvate by the hetero-complex than the homo-complex, where an efficient binding pocket of inhibitors is formed by hMPC hetero-complexes. The results of our interaction studies support this hypothesis to some degree.. This suggests that the orientation during membrane anchoring differs [4]. Our model structures of hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 also suggest that they preferentially form a hetero-complex with reverse topology [4][35]. Very recently, hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 were co-expressed and purified in yeast; however, reliable homo- and hetero-complexes were not comprehensively characterized owing to the fact that a co-expression system was studied, rather than individual expression systems [12]. Thus, an advantage of our approach is that hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 were expressed and purified using both single and co-expression systems, with the flexibility to perform accurate comparisons in each experiment. Our results indicated that hMPC-1 is thermodynamically more stable than hMPC-2 and is the main determinant of the formation of hetero-complexes. These results support those reported in previous studies wherein hMPC-1 was found to be a key molecule in mitochondrial respiration, energy generation, various cancers, and type 2 diabetic kidney disease; despite this, hMPC-2 is also important [12][13][36][37][38]. In several studies, both the homo- and heterodimers of hMPCs have been proposed as functional units [11][12]. Our results suggest that the heterodimeric state is the more stable conformation, with higher binding affinities to ligands compared with the homodimeric state. Interestingly, the homo-complexes of hMPC-1 and hMPC-2 showed different stabilities and it may be related to their function. In the pyruvate-transport mechanism of hMPC-1 and hMPC-2, the hetero-complex is still considered the main conformation in vivo. Inhibitors were selected according to their ability to block pyruvate uptake in vivo, in which hMPCs exist as a hetero-complex. Our study of the interaction between hMPCs and various ligands demonstrated that the heterodimeric state had a stronger binding affinity than those of the homodimeric states of hMPCs. Even if the binding affinity did not directly represent the pyruvate uptake ability, it was indicative of the transport energy barrier under the same conditions. For this reason, we hypothesized that it is significantly easier to transport pyruvate by the hetero-complex than the homo-complex, where an efficient binding pocket of inhibitors is formed by hMPC hetero-complexes. The results of our interaction studies support this hypothesis to some degree.

In summary, the changes in the homo- and hetero-conformation of hMPCs induced by differences in expression levels and stability are associated with cellular regulation, such as the compression of pyruvate uptake, the adjustment of protomer transcription, and the blocking of hMPC oligomerization, as well as disease generation and progression. Our results provide an insight into the detail properties of individual MPCs and provide a basis for further structural studies on MPCs.

References

- Gray, L.R.; Tompkins, S.C.; Taylor, E.B. Regulation of pyruvate metabolism and human disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 2577–2604.

- Patterson, J.N.; Cousteils, K.; Lou, J.W.; Fox, J.E.M.; MacDonald, P.E.; Joseph, J.W. Mitochondrial metabolism of pyruvate is essential for regulating glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 13335–13346.

- Colca, J.R.; McDonald, W.G.; Kletzien, R.F. Mitochondrial target of thiazolidinediones. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2014, 16, 1048–1054.

- McCommis, K.S.; Finck, B.N. Mitochondrial pyruvate transport: A historical perspective and future research directions. Biochem. J. 2015, 466, 443–454.

- Papa, S.; Francavilla, A.; Paradies, G.; Meduri, B. The transport of pyruvate in rat liver mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1971, 12, 285–288.

- PAPA, S.; PARADIES, G. On the mechanism of translocation of pyruvate and other monocarboxylic acids in rat-liver mitochondria. Eur. J. Biochem. 1974, 49, 265–274.

- Bricker, D.K.; Taylor, E.B.; Schell, J.C.; Orsak, T.; Boutron, A.; Chen, Y.C.; Cox, J.E.; Cardon, C.M.; Van Vranken, J.G.; Dephoure, N.; et al. A mitochondrial pyruvate carrier required for pyruvate uptake in yeast, Drosophila, and humans. Science 2012, 337, 96–100.

- Herzig, S.; Raemy, E.; Montessuit, S.; Veuthey, J.L.; Zamboni, N.; Westermann, B.; Kunji, E.R.; Martinou, J.C. Identification and functional expression of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Science 2012, 337, 93–96.

- Vanderperre, B.; Bender, T.; Kunji, E.R.; Martinou, J.C. Mitochondrial pyruvate import and its effects on homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 33, 35–41.

- Taylor, E.B. Functional properties of the mitochondrial carrier system. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 633–644.

- Tavoulari, S.; Thangaratnarajah, C.; Mavridou, V.; Harbour, M.E.; Martinou, J.C.; Kunji, E.R. The yeast mitochondrial pyruvate carrier is a hetero-dimer in its functional state. EMBO J. 2019, 38.

- Nagampalli, R.S.K.; Quesñay, J.E.N.; Adamoski, D.; Islam, Z.; Birch, J.; Sebinelli, H.G.; Girard, R.M.B.M.; Ascenção, C.F.R.; Fala, A.M.; Pauletti, B.A.; et al. Human mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 2 as an autonomous membrane transporter. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3510.

- McCommis, K.S.; Chen, Z.; Fu, X.; McDonald, W.G.; Colca, J.R.; Kletzien, R.F.; Burgess, S.C.; Finck, B.N. Loss of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 2 in the liver leads to defects in gluconeogenesis and compensation via pyruvate-alanine cycling. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 682–694.

- Takaoka, Y.; Konno, M.; Koseki, J.; Colvin, H.; Asai, A.; Tamari, K.; Satoh, T.; Mori, M.; Doki, Y.; Ogawa, K.; et al. Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 expression controls cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition and radioresistance. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 1331.

- Tang, X.P.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zou, H.B.; Fu, W.J.; Niu, Q.; Pan, Q.G.; Jiang, P.; Xu, X.S.; et al. Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 functions as a tumor suppressor and predicts the prognosis of human renal cell carcinoma. Lab. Investig. 2019, 99, 191.

- Gray, L.R.; Sultana, M.R.; Rauckhorst, A.J.; Oonthonpan, L.; Tompkins, S.C.; Sharma, A.; Fu, X.; Miao, R.; Pewa, A.D.; Brown, K.S.; et al. Hepatic mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 is required for efficient regulation of gluconeogenesis and whole-body glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 669–681.

- Schell, J.C.; Olson, K.A.; Jiang, L.; Hawkins, A.J.; Van Vranken, J.G.; Xie, J.; Egnatchik, R.A.; Earl, E.G.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Rutter, J. A role for the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier as a repressor of the Warburg effect and colon cancer cell growth. Mol. Cell 2014, 56, 400–413.

- Divakaruni, A.S.; Wallace, M.; Buren, C.; Martyniuk, K.; Andreyev, A.Y.; Li, E.; Fields, J.A.; Cordes, T.; Reynolds, I.J.; Bloodgood, B.L.; et al. Inhibition of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier protects from excitotoxic neuronal death. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 1091–1105.

- Ghosh, A.; Tyson, T.; George, S.; Hildebrandt, E.N.; Steiner, J.A.; Madaj, Z.; Schulz, E.; Machiela, E.; McDonald, W.G.; Galvis, M.L.E.; et al. Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier regulates autophagy, inflammation, and neurodegeneration in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, ra174–ra368.

- Zhong, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, D.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Long, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wen, J.G.; et al. Application of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier blocker UK5099 creates metabolic reprogram and greater stem-like properties in LnCap prostate cancer cells in vitro. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 37758.

- Halestrap, A.P.; Denton, R.M. Specific inhibition of pyruvate transport in rat liver mitochondria and human erythrocytes by α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamate. Biochem. J. 1974, 138, 313–316.

- Halestrap, A.P. The mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Kinetics and specificity for substrates and inhibitors. Biochem. J. 1975, 148, 85–96.

- Hildyard, J.C.; Ämmälä, C.; Dukes, I.D.; Thomson, S.A.; Halestrap, A.P. Identification and characterisation of a new class of highly specific and potent inhibitors of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics 2005, 1707, 221–230.

- Chen, Y.; McCommis, K.S.; Ferguson, D.; Hall, A.M.; Harris, C.A.; Finck, B.N. Inhibition of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier by tolylfluanid. Endocrinology 2017, 159, 609–621.

- Lehmann, J.M.; Moore, L.B.; Smith-Oliver, T.A.; Wilkison, W.O.; Willson, T.M.; Kliewer, S.A. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ). J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 12953–12956.

- Ye, J.P. Challenges in drug discovery for thiazolidinedione substitute. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2011, 1, 137–142.

- Divakaruni, A.S.; Wiley, S.E.; Rogers, G.W.; Andreyev, A.Y.; Petrosyan, S.; Loviscach, M.; Wall, E.A.; Yadava, N.; Heuck, A.P.; Ferrick, D.A.; et al. Thiazolidinediones are acute, specific inhibitors of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5422–5427.

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Kan, Q.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Xu, R.; Wang, J.; Yu, D.; Goscinski, M.A.; Wen, J.G.; et al. Mitochondrial pyruvate carrier function is negatively linked to Warburg phenotype in vitro and malignant features in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 1058.

- Guan, X.M.; Kobilka, T.S.; Kobilka, B.K. Enhancement of membrane insertion and function in a type IIIb membrane protein following introduction of a cleavable signal peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 21995–21998.

- Massotte, D. G protein-coupled receptor overexpression with the baculovirus–insect cell system: A tool for structural and functional studies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2003, 1610, 77–89.

- McCommis, K.S.; Hodges, W.T.; Brunt, E.M.; Nalbantoglu, I.; McDonald, W.G.; Holley, C.; Fujiwara, H.; Schaffer, J.E.; Colca, J.R.; Finck, B.N. Targeting the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier attenuates fibrosis in a mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2017, 65, 1543–1556.

- Corbet, C.; Bastien, E.; Draoui, N.; Doix, B.; Mignion, L.; Jordan, B.F.; Marchand, A.; Vanherck, J.C.; Chaltin, P.; Schakman, O.; et al. Interruption of lactate uptake by inhibiting mitochondrial pyruvate transport unravels direct antitumor and radiosensitizing effects. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1208.

- Li, X.; Ji, Y.; Han, G.; Li, X.; Fan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, M.; et al. MPC1 and MPC2 expressions are associated with favorable clinical outcomes in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 894.

- Bender, T.; Pena, G.; Martinou, J.C. Regulation of mitochondrial pyruvate uptake by alternative pyruvate carrier complexes. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 911–924.

- Xu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Cheung, L.S.; Fan, C.; Chen, L.Q.; Xu, S.; Perry, K.; Frommer, W.B.; Feng, L. Structures of bacterial homologues of SWEET transporters in two distinct conformations. Nature 2004, 515, 448.

- Zou, S.; Lang, T.; Zhang, B.; Huang, K.; Gong, L.; Luo, H.; Xu, W.; He, X. Fatty acid oxidation alleviates the energy deficiency caused by the loss of MPC1 in MPC1 + /- mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 1008–1013.

- Koh, E.; Kim, Y.K.; Shin, D.; Kim, K.S. MPC1 is essential for PGC-1α-induced mitochondrial respiration and biogenesis. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 1687–1699.

- Han, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, H.; Weng, W.; Yu, X.; Ge, N.; Wang, W.; Song, G.; Yi, T.; Li, S.; et al. Artemether ameliorates type 2 diabetic kidney disease by increasing mitochondrial pyruvate carrier content in db/db mice. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 1389–1402.