Botryosphaeriaceae (Botryosphaeriales) include several species reported as endophytes, latent, and woody plant pathogens on a broad range of host. The most common symptoms observed in association with species of Botryosphaeriaceae are twig, branch and trunk cankers, die-back, collar rot, root cankers, gummosis, decline and, in severe cases, plant death.

- Diplodia

- Dothiorella

- Lasiodiplodia

- Neofusicoccum

- pathogenic fungi

- phylogeny

1. Introduction

Citrus production represents one of the most important fruit industries worldwide in terms of total yield. Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain are the most important European producers of citrus fruit [1]. In 2019, nearly 11 million tons of citrus was produced in Europe on approximately 515,000 ha [2]. Most canker diseases of citrus, as well as further fruit-tree crops, are caused by a broad range of fungal species that infect the wood mainly through winter pruning wounds and a subsequent colonization of vascular tissues [3]. Several abiotic and biotic factors are considered responsible for rots and gumming on the trunk and main branches in citrus. Frost damage, sunscald, or water distribution can promote the infection of numerous ascomycetes and basidiomycetes [4]. Several fungal infections involving twigs, branches and trunks of citrus caused by

and

species were reported in different continents [5][6][7][8][9]. Guarnaccia and Crous [10] reported serious cankers developing in woody tissues of lemon trees caused by

spp., often with a gummose exudate, causing serious blight and dieback. Canker diseases of citrus are also caused by other fungal genera such as

and

[11],

[14]. Recently, significant attention has been dedicated to revising species and genera of Botryosphaeriaceae, which encompass species with a cosmopolitan distribution that are able to cause diseases of numerous plant species worldwide [15][16].

Botryosphaeriaceae (Botryosphaeriales) include several species reported as endophytes, latent, and woody plant pathogens on a broad range of host [15][16][17]. This family has undergone significant revision after the adoption of molecular tools to resolve its taxonomy [15][16][18][19][20][21][22][23]. Recently, the taxonomy of Botryosphaeriaceae (and other families in Botryosphaeriales) has been reviewed by Phillips et al. [23] based on morphology of the sexual morphs, phylogenetic relationships on internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and 28S large subunit (LSU) of nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA) sequences and evolutionary divergence times. The authors highlighted the main findings made by Yang et al. [16] who included new families, genera, and species in Botryosphaeriales based on morphology and multi-marker phylogenetic analyses of a large collection of isolates. Currently, six families are accepted in Botryosphaeriales and 22 genera have been included in Botryosphaeriaceae [23][24][25].

The most common symptoms observed in association with species of Botryosphaeriaceae are twig, branch and trunk cankers, die-back, collar rot, root cankers, gummosis, decline and, in severe cases, plant death [15][17]. Plant infections mainly occur through natural openings or wounds, but these fungal species could also survive in latency. This ability could lead to their spread worldwide through asymptomatic plant material, seedlings and fruit, frequently circumventing the adopted quarantine measures [22]. Moreover, stress and non-optimal plant growth conditions consistently induce the expression of diseases associated with Botryosphaeriaceae species. Thus, global warming could increase plant stress and induce favourable conditions for the development of Botryosphaeriaceae diseases [17][26][27]. Species within the Botryosphaeriaceae represent a serious threat to different crops including major fruit, berry fruit and nut crops cultivated in sub-tropical, tropical, or temperate areas [22][28][29][30].

Several species of

(

.),

(

.),

,

and

(

.) have been previously reported to affect

species [13][31][32][33]. For example,

has been reported causing citrus branch canker in California [13] and Italy [32];

.

,

.

,

and

have been described in association with branch and trunk dieback of citrus trees in Iran [14][34] and

spp. have been detected as causal agents of citrus gummosis in Tunisia [35]. Moreover,

,

,

,

and

have been recovered from symptomatic citrus trees in Algeria [33].

2. Results

2.1. Field Sampling and Fungal Isolation

2. Field Sampling and Fungal Isolation

In this study, the sampling focused on symptomatic plants of

,

,

,

×

and

. Samples were collected in 19 orchards. Citrus trees showed various external disease symptoms, including partial or complete yellowing, wilting leaves and twigs, and dieback of branch tips, but also defoliation and branch decline. Canker and cracking of the bark associated with gummose exudate occurred on trunks and branches. Internal observation of infected branches revealed black to brown wood discoloration in cross-sections, wedge-shaped necrosis or irregular wood discoloration. Twigs were wilted and occasionally presenting sporocarps (

). Symptoms were detected in all the orchards and regions investigated. A total of 63 fungal isolates were collected and were found to be characterized by dark green to grey, fast-growing mycelium on MEA. Moreover, the isolates produced pycnidia on pine needles within 40 days, containing pigmented or hyaline conidia. According to these characteristics, the fungal isolates were classified as Botryosphaeriaceae spp. based on comparison with the previous generic descriptions [15]. Among the collected isolates, 18 were obtained from trunk cankers, 10 were associated with branch infections, and 35 from twig dieback.

Symptoms on citrus tissues with associated Botryosphaeriacae species. (

) Branch decline in commercial lemon orchard. (

) Trunk canker and bark cracking of

(

,

) Trunk and branch canker with gummosis of

.

plants. (

,

) External cracking with gummosis and internal wood discoloration of the same affected branch of

plant. (

,

) Internal wood discoloration and branch blight of

. (

) Twig dieback of young

×

and

(

) plants.

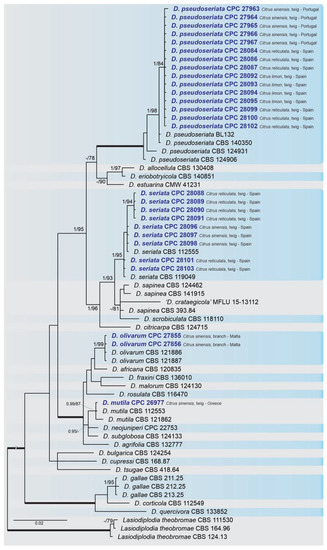

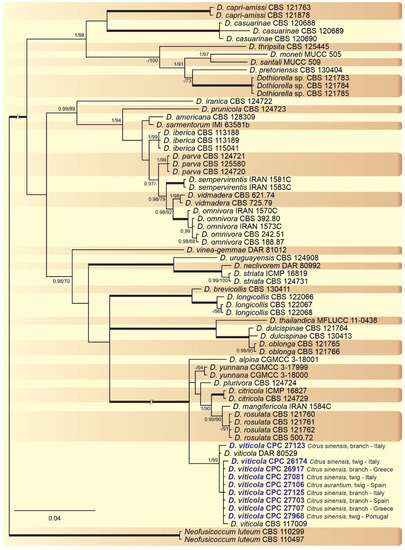

2.2. Phylogenetic Analyses

3. Phylogenetic Analyses

A combined multi-marker (ITS,

, and

) phylogenetic tree was inferred for each genus (

,

,

, and

) obtained in this study (

,

,

and

). The best nucleotide models for the Bayesian Inference analysis of each dataset were as follows: SYM (symmetrical model) + I (proportion of invariable sites) + G (gamma distribution) (

,

,

, and

) for ITS; GTR (generalized time-reversible model) + G (

,

and

) and HKY (Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano) + I + G (

) for

and GTR + G (

,

and

) and GTR + I + G (

) for

. The

phylogenetic analysis revealed the isolates as belonging to

(15 isolates, BPP = 1 and ML-BS = 100),

(9 isolates, BPP = 1 and ML-BS = 95),

(2 isolates, Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) = 1 and maximum likelihood bootstrapped (ML-BS) = 99), and

(1 isolate, BPP = 0.99 and ML-BS = 87) (

). The

phylogeny (

) grouped the isolates together within

(9 isolates, BPP = 1 and ML-BS = 99). The

phylogenetic analysis placed five isolates as

(BPP = 1 and ML-BS = 98) (

). The

phylogeny (

) grouped sequences from our isolates as belonging to

(2 isolates, BPP = 1 and ML-BS = 94),

(16 isolates) and

(4 isolates, BPP = 1 and ML-BS = 98).

Bayesian inference analysis of

species using ITS rDNA,

and

sequences. Isolates obtained in this study are in bold and blue. Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) and maximum likelihood-bootstrap (ML-BS) values equal or greater than 0.95 and 70%, respectively, are shown near nodes. Thickened branches represent clades with ML-BS = 100% and a BPP = 1.0. The tree was rooted to

(CBS 111530, CBS 164.96 and CBS 124.13).

Bayesian inference analysis of

species using ITS rDNA,