Plant-beneficial Pseudomonas spp. aggressively colonize the rhizosphere and produce numerous secondary metabolites, such as 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG). DAPG is a phloroglucinol derivative that contributes to disease suppression, thanks to its broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. A famous example of this biocontrol activity has been previously described in the context of wheat monoculture where a decline in take-all disease (caused by the ascomycete Gaeumannomyces tritici) has been shown to be associated with rhizosphere colonization by DAPG-producing Pseudomonas spp.

- 2

- 4-diacetylphloroglucinol

- DAPG

- Pseudomonas

- biocontrol

- antibiotic

1. Introduction

Hypericum

Eucalyptus species, to the more complex phlorotannins found in several families of brown algae [2][3]. These compounds often exhibit antiviral, antibacterial and antifungal activity [2]. Phloroglucinol derivatives are also produced by some microorganisms [2][4]. By contrast with the phloroglucinol derivatives found in plants and brown algae, phloroglucinol derivatives of microbial origin are rather simple. Some

Pseudomonas

Pseudomonas spp. have received particular attention due to their ability to control numerous soil-borne plant diseases, including take-all of wheat, tobacco black root rot and sugar beet damping-off [4][5]. These bacteria also play an important role in natural disease suppressiveness found in several soils across the world. Besides their presence in the rhizosphere, DAPG-producing

Pseudomonas

Pseudomonas

Pseudomonas spp. and their role in take-all decline [4][9].

2. Genetics, Biochemistry, and Evolution of DAPG Biosynthesis

2.1. The Phl Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

Pseudomonas

Pseudomonas sp. Q2-87 [10][11],

P

kilonensis

P

protegens

Pseudomonas

phl

phlABCD

phlE

phlF

phlG

phlH

phlI, which encodes an uncharacterized protein [16][17]. The organization of the

phl

Pseudomonas

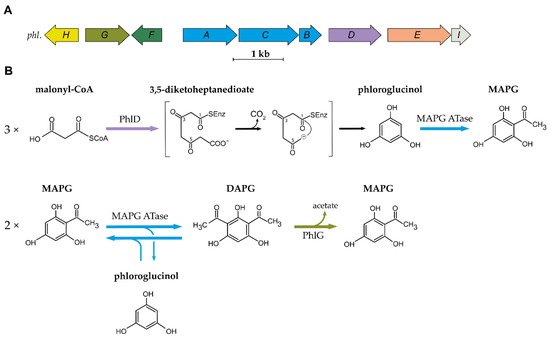

Figure 1.

A

phl

Pseudomonas

B

Pseudomonas

2.2. Biosynthesis and Degradation of DAPG

The first step in the biosynthesis of DAPG is catalysed by the type III polyketide synthase (PKS) PhlD [14][19]. Type III PKSs are homodimeric enzymes that catalyse the iterative condensation of a starter substrate (usually an acyl-CoA) with several extender substrate units (usually malonyl-CoA) to generate a linear polyketide, which is subsequently cyclized [20]. Bangera and Thomashow [14] proposed that PhlD uses acetoacetyl-CoA as the starter substrate to produce monoacetylphloroglucinol (MAPG), but it was later showed that PhlD produces phloroglucinol from malonyl-CoA instead [19]. While PhlD uses malonyl-CoA as a preferred substrate, it also accepts other starter substrates with an aliphatic chain of C

4

12 in vitro [21]. The proposed mechanism leading to the formation of phloroglucinol is that PhlD catalyses the iterative condensation of three molecules of malonyl-CoA into 3,5-diketoheptanedioate [19]. This polyketide intermediate undergoes decarboxylation and is subsequently cyclized via a Claisen condensation, leading to the formation of phloroglucinol [19][21].

P

kilonensis

phlACB

phlACB

E

coli

phlACB

The MAPG ATase also catalyses the reverse reaction, yielding two molecules of MAPG from a molecule of DAPG and a molecule of phloroglucinol [17]. This results in an equilibrium where DAPG, MAPG and phloroglucinol are present at quasi-equimolar concentration. Recent studies have provided new insight into the catalytic properties, the mechanism, and the structure of the MAPG ATase [23][24][25][26][27]. This enzyme was shown to use various non-natural substrates as acyl-donor in in vitro experiments [26][27][28]. This is particularly interesting given the fact that the acyl donor involved in MAPG biosynthesis from phloroglucinol remains to be characterized. The crystal structure revealed that PhlACB subunits are arranged in a Phl(A

2

2

2

4

DAPG is degraded by the zinc-dependent hydrolase PhlG [29][30]. PhlG degrades DAPG into MAPG and acetate by cleaving one of the C-C bonds linking the acetyl groups to the phenolic ring [29][30]. This enzyme is highly specific for its substrate DAPG, as it is unable to degrade structurally similar compounds, such as MAPG or triacetylphloroglucinol [29]. The crystal structure of PhlG revealed that it cleaves C-C bonds using a Bet v1-like fold domain, contrary to the alpha/beta fold classically used by hydrolases [30].

2.3. Distribution and Evolution of the Phl Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

phl

P

corrugata

P

protegens

P

fluorescens

phl BCG is not present in all the strains belonging to these two subgroups, and its distribution in these two subgroups is patchy [18][31][32].

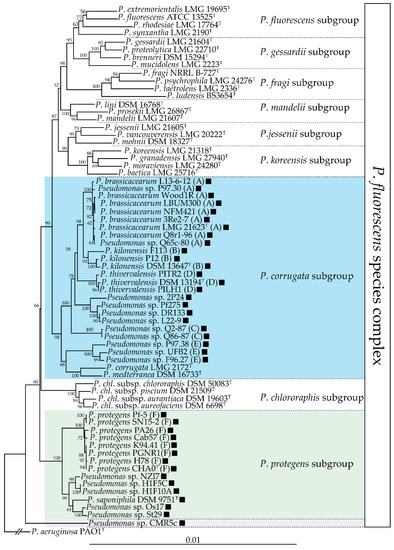

Figure 2.

phl

P

fluorescens

gyrB

rpoB

rpoD

phl

phl

P

corrugata

phl

P

corrugata

P

corrugata

P

mediterranea [36][37]. These phytopathogenic strains do not harbour the

phl BCG, suggesting that this cluster could have been lost during the transition between commensal and pathogenic lifestyles. The fact that DAPG can trigger induced systemic resistance in some plant species [38][39][40] is an undesirable trait for a plant pathogen, which means that it could have been counter-selected in these lineages. Outside of these two subgroups, the

phl

P

fluorescens species complex [18][41]. The

phl

Pseudomonas

phl

Betaproteobacteria

Pseudogulbenkiania ferrooxidans

Chromobacterium vaccinii

Chromobacterium

phl

P

fluorescens species complex is an ancestral event [16][18][42]. The

phl

Pseudomonas

Pseudomonas

phl

phlACB