The field of mRNA has made significant progress in the last ten years and has emerged as a highly attractive means of encoding and producing any protein of interest in vivo. Through the natural role of mRNA as a transient carrier of genetic information for translation into proteins, in vivo expression of mRNA-encoded antibodies offer many advantages over recombinantly produced antibodies.

- mRNA

- antibody

- immunotherapy

1. Introduction

Antibodies are components of the human adaptive immune system that are crucial to prevent, control and resolve infections [1]. Prior to the introduction of antibiotics and vaccines, passive transfer of serum containing antibodies from convalescent individuals or animals was the “standard of care” against infectious diseases [2]; this approach is still used today to treat venomous snake bites, toxin exposure, rabies and, more recently, the Ebola virus and SARS-CoV-2 infections [3,4,5][3][4][5]. Over the last two decades, the field of antibody-mediated immunotherapy has been transformed by the development of methods to immortalize B cells [6]. Further breakthroughs in recombinant antibody technologies, such as antibody isolation and gene sequencing, have resulted in the regulatory approval and commercialization of over 100 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to treat autoimmune diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, cancer and infectious disease [7,8,9,10][7][8][9][10]. To date, all licensed mAbs are purified IgG proteins that are administered intravenously (IV), intramuscularly (IM) or subcutaneously (SC) [2,8][2][8].

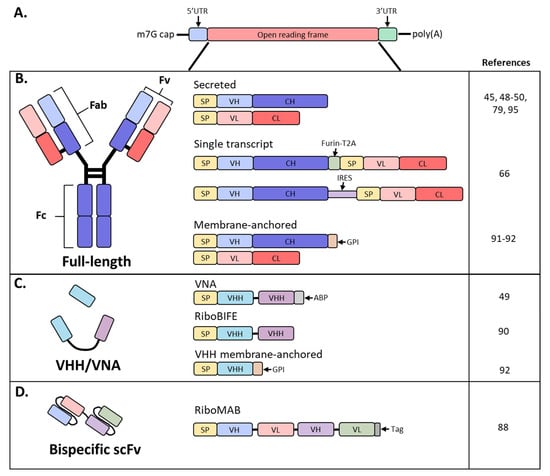

Antibodies are hetero-tetrameric proteins formed by two full-length heavy (H) and light (L) chains held together via charge–charge interactions and disulfide bonds. Two distinct parts of an antibody are critical for its function: the antigen binding fragment (Fab) and the crystallizable fragment (Fc) (Figure 1). The Fab region determines antibody specificity and is composed of one constant and one variable domain (Fv) of the H and L chains. The Fc region, comprised of the constant domains of two H chains, determines the in vivo antibody half-life by binding to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) [11,12] [11][12] and can modulate immune cell activity through binding to Fc receptors on innate immune cells [13]. The Fc effector functions can be altered by post-translational modifications such as glycosylation, methionine oxidation or deamidation, which can also impact antibody distribution and stability [14,15,16][14][15][16].

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of mRNA and antibody designs used in recent studies. (A) Basic structure of an mRNA construct; (B) different formats used by recent studies to encode a full-length antibody as mRNA; (C) derivatives of full-sized antibodies that are comprised of only the heavy chain; (D) bispecific antibody, single-chain variable fragment (scFv) format; SP, signal peptide; VH, variable heavy chain domain; CH, constant heavy chain domain; VL, variable light chain domain; CL, constant light chain domain; Furin-T2A, furin and thosea asigna virus 2A peptide; IRES, internal ribosomal entry site; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane anchor; VHH, VH domain, heavy chain only.

2. mRNA as a Platform for Efficient Protein

Expression In VivomRNA synthesis starts with in vitro transcription (IVT) by RNA polymerases of a linear DNA template that contains a promoter, 5’ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs), and an open reading frame [53][17]. Two additional elements are required for the mRNA to be biologically active: an inverted triphosphate cap at the 5′ end and a poly(A) tail at the 3′ end. Both a cap and poly(A) tail are required for efficient translation and stabilization of the mRNA, and both elements can be added either during transcription or enzymatically after [54][18]. Importantly, cap structure [19] [55] and poly(A) tail lengths [20] [56] can impact the amount of protein produced by an mRNA-based therapy (Figure 1A). Other factors that can affect mRNA translation or half-life include UTRs ][21][22][23] [57,58,59] and codon optimization [60][24]; the work of understanding and balancing these mRNA elements is an area of intense research.Protein expression from exogenous mRNA was demonstrated in vivo two decades ago when direct injection of mRNA into mouse muscle was shown to result in local protein expression [61][25]; however, there are still several hurdles that need to be solved. First and foremost, mRNA is an unstable molecule that is degradable by ribonucleases in the body resulting in a very short half-life. Additionally, naked mRNA is not efficiently delivered to cells and mRNA can activate innate immune pathways that may decrease protein expression [52][26]. In the last decade, significant progress has been made in all these areas.

3. Modified mRNA

mRNA and the side products of the mRNA in vitro transcription (IVT) process can trigger an innate immune response through pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) receptors, such as toll-like receptor (TLR)3, TLR7, TLR8, retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 (RIG-I) and nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain containing protein 2-(NOD-2), which recognize either double-or single-stranded RNA [52][26]. Activation of the innate immune pathways could interfere with therapeutic applications by decreasing protein expression and undermining tolerability. Modified bases found in natural RNAs have been revealed to not only suppress recognition by TLRs in vivo but also to increase the stability and translation of mRNA [42,43][27][28]. A common modification is replacement of uridine with pseudouridine, which has been shown to increase mRNA translation and decrease innate immune stimulation [43,62][28][29]. Further reduction in stimulation of innate immunity has been obtained by stringent mRNA purification by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), which can remove the aberrant RNAs created in the IVT reaction [63,64][30][31].

4. Self-Amplifying mRNA

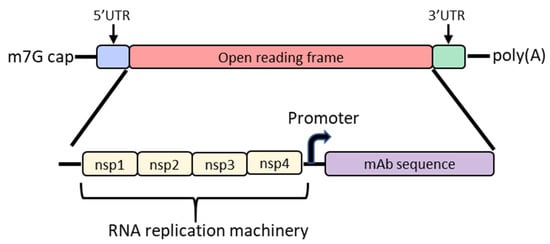

In order to increase protein expression and decrease mRNA dose, some groups have developed a self-amplifying mRNA (SAM) approach based on the alphavirus genome that encodes its own RNA replication machinery [65,66][32][33]. Due to the bipartite division of structural and nonstructural regions in the alphavirus genome, structural genes can be replaced with genes of interest while still retaining the machinery for replicative functions (Figure 2). However, there are significant drawbacks to this approach, largely due to the sheer size of the construct and their intrinsically high innate immune stimulation. To encode the polymerase, replicons start at a size of ~7.6 kb; the addition of the gene of interest results in a large construct that is prone to cleavage and therefore unstable [67,68,69][34][35][36]. As such, large-scale manufacturing, storage and characterization of these constructs are quite complex and expensive and constitute an active area of research in the field [65,68][32][35]. To overcome the difficulties of SAM resulting from size, the replicase can be provided in trans [70][37]. While this results in shorter mRNAs, it requires manufacturing of at least two RNAs and efficient delivery of both into the same cell. Another disadvantage of SAMs is their intrinsic immunogenicity due to the formation of short double-stranded RNA during production and self-amplification [68][35]. There will need to be significant improvements in the stability of long mRNAs, immunogenicity and more complex manufacturing before SAM can become a realistic option in the clinic to produce monoclonal antibodies in vivo.

Figure 2. Diagram of the basic structure of self-amplifying mRNA (RepRNA) that includes the typical cap, 5′ and 3′ UTRs and poly(A) tail. The details of the open reading frame are depicted and contain the nsp1, nsp2, nsp3 and nsp4 genes from the alphavirus genome that encode for RNA replication machinery. Downstream from the rep genes are a subgenomic promoter and the elements encoding a monoclonal antibody (mAb). Abbreviations: m7G: 7-methylguanosine; UTR: untranslated region; nsp: nonstructural protein.

References

- Plotkin, S.A. Correlates of Protection Induced by Vaccination. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010, 17, 1055–1065.

- Hale, G. Therapeutic antibodies—Delivering the promise? Adv. Drug Deliver. Rev. 2006, 58, 633–639.

- Shen, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Wang, F.; Li, D.; Yang, M.; Xing, L.; et al. Treatment of 5 Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19 with Convalescent Plasma. JAMA 2020, 323, 1582–1589.

- Sparrow, E.; Torvaldsen, S.; Newall, A.T.; Wood, J.G.; Sheikh, M.; Kieny, M.P.; Abela-Ridder, B. Recent advances in the development of monoclonal antibodies for rabies post exposure prophylaxis: A review of the current status of the clinical development pipeline. Vaccine 2018, 37, A132–A139.

- Chippaux, J.-P.; Boyer, L.V.; Alagón, A. Post-exposure treatment of Ebola virus using passive immunotherapy: Proposal for a new strategy. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins 2015, 21, 3.

- Köhler, G.; Milstein, C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 1975, 256, 495–497.

- Kaplon, H.; Muralidharan, M.; Schneider, Z.; Reichert, J.M. Antibodies to watch in 2020. MABs 2019, 12, 1703531.

- Ecker, D.M.; Jones, S.D.; Levine, H.L. The therapeutic monoclonal antibody market. MABs 2015, 7, 9–14.

- Tiller, T.; Meffre, E.; Yurasov, S.; Tsuiji, M.; Nussenzweig, M.C.; Wardemann, H. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J. Immunol. Methods 2008, 329, 112–124.

- Hoogenboom, H.R. Selecting and screening recombinant antibody libraries. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 1105–1116.

- Nimmerjahn, F.; Ravetch, J.V. Antibodies, Fc receptors and cancer. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007, 19, 239–245.

- Pyzik, M.; Sand, K.M.K.; Hubbard, J.J.; Andersen, J.T.; Sandlie, I.; Blumberg, R.S. The Neonatal Fc Receptor (FcRn): A Misnomer? Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1540.

- Mkaddem, S.B.; Benhamou, M.; Monteiro, R.C. Understanding Fc Receptor Involvement in Inflammatory Diseases: From Mechanisms to New Therapeutic Tools. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 811.

- Jennewein, M.F.; Alter, G. The Immunoregulatory Roles of Antibody Glycosylation. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 358–372.

- Lu, X.; Machiesky, L.A.; Mel, N.D.; Du, Q.; Xu, W.; Washabaugh, M.; Jiang, X.R.; Wang, J. Characterization of IgG1 Fc Deamidation at Asparagine 325 and Its Impact on Antibody-dependent Cell-mediated Cytotoxicity and FcγRIIIa Binding. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 383.

- Cymer, F.; Thomann, M.; Wegele, H.; Avenal, C.; Schlothauer, T.; Gygax, D.; Beck, H. Oxidation of M252 but not M428 in hu-IgG1 is responsible for decreased binding to and activation of hu-FcγRIIa (His131). Biologicals 2017, 50, 125–128.

- Sahin, U.; Karikó, K.; Türeci, Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics—developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 759–780.

- Shuman, S. Catalytic Activity of Vaccinia mRNA Capping Enzyme Subunits Coexpressed in Escherichia coZi*. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 11960–11966.

- Ramanathan, A.; Robb, G.B.; Chan, S.-H. mRNA capping: Biological functions and applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 7511–7526.

- Holtkamp, S.; Kreiter, S.; Selmi, A.; Simon, P.; Koslowski, M.; Huber, C.; Türeci, O.; Sahin, U. Modification of antigen-encoding RNA increases stability, translational efficacy, and T-cell stimulatory capacity of dendritic cells. Blood 2006, 108, 4009–4017.

- Guhaniyogi, J.; Brewer, G. Regulation of mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Gene 2001, 265, 11–23.

- Leppek, K.; Das, R.; Barna, M. Functional 5′ UTR mRNA structures in eukaryotic translation regulation and how to find them. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 158–174.

- von Niessen, A.G.O.; Poleganov, M.A.; Rechner, C.; Plaschke, A.; Kranz, L.M.; Fesser, S.; Diken, M.; Löwer, M.; Vallazza, B.; Beissert, T.; et al. Improving mRNA-based therapeutic gene delivery by expression augmenting 3’-untranslated regions identified by cellular library screening. Mol. Ther. 2018, 27, 824–836.

- Mauger, D.M.; Cabral, B.J.; Presnyak, V.; Su, S.V.; Reid, D.W.; Goodman, B.; Link, K.; Khatwani, N.; Reynders, J.; Moore, M.J.; et al. mRNA structure regulates protein expression through changes in functional half-life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 24075–24083.

- Wolff, J.; Malone, R.; Williams, P.; Chong, W.; Acsadi, G.; Jani, A.; Felgner, P.L. Direct gene transfer into mouse muscle in vivo. Science 1990, 247, 1465–1468.

- Nelson, J.; Sorensen, E.W.; Mintri, S.; Rabideau, A.E.; Zheng, W.; Besin, G.; Khatwani, N.; Su, S.V.; Miracco, E.J.; Issa, W.J.; et al. Impact of mRNA chemistry and manufacturing process on innate immune activation. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz6893.

- Karikó, K.; Buckstein, M.; Ni, H.; Weissman, D. Suppression of RNA Recognition by Toll-like Receptors: The Impact of Nucleoside Modification and the Evolutionary Origin of RNA. Immunity 2005, 23, 165–175.

- Karikó, K.; Muramatsu, H.; Welsh, F.A.; Ludwig, J.; Kato, H.; Akira, S.; Weissman, D. Incorporation of Pseudouridine Into mRNA Yields Superior Nonimmunogenic Vector With Increased Translational Capacity and Biological Stability. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 1833–1840.

- Svitkin, Y.V.; Cheng, Y.M.; Chakraborty, T.; Presnyak, V.; John, M.; Sonenberg, N. N1-methyl-pseudouridine in mRNA enhances translation through eIF2α-dependent and independent mechanisms by increasing ribosome density. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 6023–6036

- Triana-Alonso, F.J.; Dabrowski, M.; Wadzack, J.; Nierhaus, K.H. Self-coded 3′-Extension of Run-off Transcripts Produces Aberrant Products during in Vitro Transcription with T7 RNA Polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 6298–6307.

- Gholamalipour, Y.; Karunanayake Mudiyanselage, A.; Martin, C.T. 3′ end additions by T7 RNA polymerase are RNA self-templated, distributive and diverse in character—RNA-Seq analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 9253–9263.

- Geall, A.J.; Verma, A.; Otten, G.R.; Shaw, C.A.; Hekele, A.; Banerjee, K.; Cu, Y.; Beard, C.W.; Brito, L.A.; Krucker, T.; et al. Nonviral delivery of self-amplifying RNA vaccines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14604–14609.

- Erasmus, J.H.; Archer, J.; Fuerte-Stone, J.; Khandhar, A.P.; Voigt, E.; Granger, B.; Bombardi, R.G.; Govero, J.; Tan, W.; Durnell, L.A.; et al. Intramuscular delivery of replicon RNA encoding ZIKV-117 human monoclonal antibody protects against Zika virus infection. Mol. Ther.-Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 18, 402–414.

- Melton, D.A.; Krieg, P.A.; Rebagliati, M.R.; Maniatis, T.; Zinn, K.; Green, M.R. Efficient in vitro synthesis of biologically active RNA and RNA hybridization probes from plasmids containing a bacteriophage SP6 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984, 12, 7035–7056.

- Bloom, K.; van den Berg, F.; Arbuthnot, P. Self-amplifying RNA vaccines for infectious diseases. Gene Ther. 2020, 1–13.

- Krieg, P.A. Improved synthesis of full-length RNA probe at reduced incubation temperatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990, 18, 6463.

- Beissert, T.; Perkovic, M.; Vogel, A.; Erbar, S.; Walzer, K.C.; Hempel, T.; Brill, S.; Haefner, E.; Becker, R.; Türeci, O.; et al. A trans-amplifying RNA vaccine strategy for induction of potent protective immunity. Mol. Ther. 2019, 28, 119–128.