Status epilepticus (SE) carries an exceedingly high mortality and morbidity, often warranting an aggressive therapeutic approach. Recently, the implementation of a ketogenic diet (KD) in adults with refractory and super-refractory SE has been shown to be feasible and effective. We describe our experience, including the challenges of achieving and maintaining ketosis, in an adult with new onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE).

- ketogenic diet

- status epilepticus

- new onset refractory status epilepticus

- seizures

- critical care

- ketosis

1. Introduction

Status epilepticus (SE) carries an exceedingly high mortality and morbidity, often warranting an aggressive therapeutic approach. Recently, the implementation of ketogenic diet (KD) in adults with refractory and super-refractory SE has been shown to be feasible and potentially effective [1][2][3][4][5]. Most often used in childhood epilepsies, KD has emerged as a potential adjunctive treatment for pediatric SE [6][7]. We describe our experience with an adult with new onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) focusing on the unexpected challenge of achieving and maintaining ketosis. Practical advice, and a comprehensive review of factors potentially jeopardizing ketosis commonly encountered in the critical care setting and alternatives are provided.

2. Ketogenic Diet

Ketosis is commonly defined as sustained beta-hydroxybutyrate levels > 2 mmol/L [8] or a urinary acetoacetate level of >40 mg/dL [9]. There is evidence supporting the use of KD in children with autoimmune epilepsies, symptomatic epilepsy syndromes, pediatric refractory and super-refractory SE [6][10]. In a study of 10 children (age six months—16 years old) with refractory focal SE, initiation of a KD resulted in lower seizure burden (50% reduction in seizures for 70% of the cohort) and resolution of seizures in 20% [6]. In the minority of patients with less than 50% seizure reduction (

Ketosis is commonly defined as sustained beta-hydroxybutyrate levels > 2 mmol/L [30] or a urinary acetoacetate level of >40 mg/dL [31]. There is evidence supporting the use of KD in children with autoimmune epilepsies, symptomatic epilepsy syndromes, pediatric refractory and super-refractory SE [6,32]. In a study of 10 children (age six months—16 years old) with refractory focal SE, initiation of a KD resulted in lower seizure burden (50% reduction in seizures for 70% of the cohort) and resolution of seizures in 20% [6]. In the minority of patients with less than 50% seizure reduction (n = 3), severe adverse events (pancreatitis or severe vomiting and hypoglycemia) prompted KD discontinuation. In another study of 12 children with fever induced refractory epileptic encephalopathy, KD was able to stop seizures within two days following ketonuria [10]. Nevertheless, the side effects of KD limit its widespread use, and successful ketosis must be attained for seizure control.

= 3), severe adverse events (pancreatitis or severe vomiting and hypoglycemia) prompted KD discontinuation. In another study of 12 children with fever induced refractory epileptic encephalopathy, KD was able to stop seizures within two days following ketonuria [32]. Nevertheless, the side effects of KD limit its widespread use, and successful ketosis must be attained for seizure control.More recently, KD has been evaluated in adult patients; a systematic review of 38 adult patients with RSE or SRSE demonstrated that 82% were able to achieve SE cessation with KD [11]. There are several complex mechanisms for the efficacious effect of KD on reducing seizure activity, which result from reduction in glucose intake, ketone body production and alteration of the gut microbiome. The metabolic changes induced by KD alter the balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters, lead to reductions in oxidative stress and systemic as well as neuroinflammation, and have further long-term effects on gene expression [3][12].

More recently, KD has been evaluated in adult patients; a systematic review of 38 adult patients with RSE or SRSE demonstrated that 82% were able to achieve SE cessation with KD [33]. There are several complex mechanisms for the efficacious effect of KD on reducing seizure activity, which result from reduction in glucose intake, ketone body production and alteration of the gut microbiome. The metabolic changes induced by KD alter the balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters, lead to reductions in oxidative stress and systemic as well as neuroinflammation, and have further long-term effects on gene expression [3,34].We sought KD as a rescue therapy after conventional treatments had failed.

3. Question: Should You Fast the Patient to Achieve Ketosis Quickly? If So, How Long and What Are Potential Consequences? If You Decide Not to Fast, Can Ketosis Still Be Achieved?

Variations in KD Protocols

Historically, KD implementation in the setting of childhood epilepsy included an initial fasting period ranging anywhere from 12 [7] to 48 [13][14] hours or more. Once satisfactory ketosis is achieved, ketogenic formulations or meals (typically 4:1 g of fat: carbohydrate + protein ratio) can then be titrated as tolerated until full caloric requirements are met. To avoid potential complications of a fasting period (e.g., dehydration, hypoglycemia), Kim et al. began KD without initial fasting and found equivalency in time to ketosis and seizure reduction in 41 children with intractable epilepsy compared to a retrospective control population of 83 children who fasted prior to KD initiation [15]. While rates of hypoglycemia were similar when compared to controls, there were reduced rates of dehydration and reduced length of hospital stay.

An alternative, yet equally efficacious approach for childhood epilepsy, does not involve initial fasting or limiting caloric intake. This protocol differs from others in the fact that there is a gradual increase from 1:1 to 2:1 until the goal 4:1 ratio is reached [14]. This gradual induction and establishment of ketosis in children diagnosed with intractable epilepsy showed an equal reduction in seizure activity yet decreased weight loss and episodes of hypoglycemia, acidosis and dehydration. Nevertheless, since time is a major factor in terms of avoiding neurologic and systemic consequences of SE, a more aggressive approach to KD initiation (i.e., fasting and/or more rapidly advancing to full calories as tolerated) may be warranted in this setting.

Individual patient characteristics including age, illness severity, duration of anesthetic use prior to diet initiation resulting in reduction in gastrointestinal motility, and diet complications, may not allow the luxury of initiating a preferred protocol with certain ketogenic ratio or at a faster rate. This was evident in Cobo’s pediatric SRSE study in which ratios were started as low as 0.75:1 in some instances, and ratios never exceeding 2:1 in some cases [7]. The need for higher protein intake (often in cases of poor wound healing, malnutrition and/or low basal resting energy expenditure) challenges the use of higher fat:protein + carbohydrate ratios, although this is more of a concern with chronic KD use rather than in the acute setting of RSE and SRSE. A possible way to maximize ketosis when using lower ratios (thus, higher protein intake) is the addition of medium-chain triglyceride oils as they yield greater amounts of ketones/kcal of energy than longer chain varieties [13].

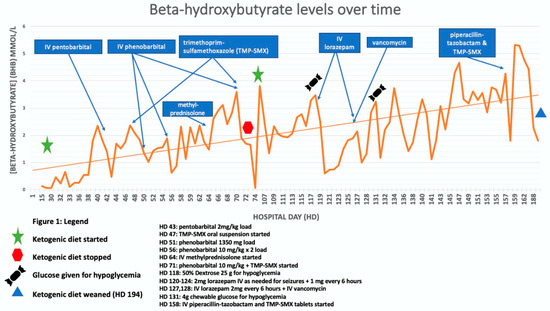

We used these principles, most frequently used in the setting of childhood epilepsy, to initiate KD for our NORSE patient with the goal of achieving ketosis quickly. Our patient was initially started on KD on hospital day 28 (HD 28) with a goal of 5:1 ratio (KetoCal® 4:1 at 55 mL/h plus 33 mL medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) oil to balance carbohydrate intake from medications, documented as 51 g daily on HD 30). At this time, supplemental protein via PROsource® was discontinued to assist with achieving ketosis. On HD 35, beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) levels continued to show inadequate ketosis [Figure 1] prompting the increase to 6:1 with additional MCT Oil. Through HD 65, beta-hydroxybutyrate continued to fluctuate below the 2.0 goal. On HD 71, beta-hydroxybutyrate again dropped with the only documented potential carbohydrate source (at that time) being a milk and molasses enema administered by a care team to alleviate constipation. The decision was made to return to a higher carbohydrate-containing formula and refocus nutrition goals on wound healing. At this time, our patient was identified as meeting the criteria for severe malnutrition based on weight loss of >7.5% in three months and limited energy intake for greater than or equal to five days [16].

Figure 1.

4. Question: Aside from Sedative Agents, What Other Widely Used Agents in the Neurological ICU Can Hinder Ketosis?

4.1. Antimicrobials and Respective Diluents as Source of Carbohydrates

Various antibiotics that are used frequently in the neurological ICU [17][18] can hinder ketosis. Intravenous trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX, Bactrim

®) requires reconstitution with dextrose 5% water and, similarly, vancomycin is often diluted in dextrose 5% water prior to intravenous administration.

Figure 1 (line graph) shows several instances in which administration of TMP-SMX and vancomycin were associated with troughs in beta-hydroxybutyrate levels.

4.2. Non “Medications” Contain Hidden Carbohydrates

TM), reported to be superior to toothbrushing at reducing early ventilator-associated pneumonia [19], contains glycerin and ethyl alcohol, both carbohydrate-containing substances that can affect KD [20]. Oral fiber supplements, such as psyllium, have a significant carbohydrate load (e.g., 9 g/tablespoon). However, as fiber has a lower glycemic index compared to other carbohydrate-containing sources in the ICU setting, it may still be used in some instances to counteract constipation.

4.3. Comprehensive Approach to Implementing KD in Adult SE

Table 1 with a summary of the suggested steps for successful KD initiation [4].

Table 13.

| Pearls to Consider for Starting and Maintaining a Ketogenic Diet (KD) |

|---|

| I. KD initiation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| II. KD maintenance |

|

| III. Pitfalls to consider: |

|