Phosphorus (P) is a vital element in biological molecules, and one of the main limiting elements for biomass production as plant-available P represents only a small fraction of total soil P. Increasing global food demand and modern agricultural consumption of P fertilizers could lead to excessive inputs of inorganic P in intensively managed croplands, consequently rising P losses and ongoing eutrophication of surface waters. Despite phosphate solubilizing microorganisms (PSMs) are widely accepted as eco-friendly P fertilizers for increasing agricultural productivity, a comprehensive and deeper understanding of the role of PSMs in P geochemical processes for managing P deficiency has received inadequate attention. In this review, we summarize the basic P forms and their geochemical and biological cycles in soil systems, how PSMs mediate soil P biogeochemical cycles, and the metabolic and enzymatic mechanisms behind these processes. We also highlight the important roles of PSMs in the biogeochemical P cycle and provide perspectives on several environmental issues to prioritize in future PSM applications.

- phosphate solubilizing microorganisms

- soil P

- P forms

- P biogeochemical cycle

1. Introduction

Phosphorus (P) is a macronutrient that plays essential roles in plant growth and participates in many metabolic reactions [1]. It is a vital element for life as it is present in biological molecules, including nucleic acids, co–enzymes, phosphoproteins, and phospholipids [2][3][4]. Additionally, P is one of the main limiting elements for biomass production in terrestrial ecosystems and the reason for the ongoing eutrophication of continental and coastal waters because of extensive utilization of P–fertilizers [5][6][7]. The P cycle exists within individual ecosystems including soil, stream, forest, and marine, which are closely related to key security issues of surrounding environment and human society [6][8][9][10].

P cycle differs from the N and C biogeochemical cycles since it does not form any stable gaseous species at Earth temperatures and atmospheric pressures [11][12]. Only small amounts of phosphoric acid (H3PO4) may enter the atmosphere and contribute to acid rain in some cases [13]. P emitted by combustion of fossil fuels and biofuels into the atmosphere, which has been listed as one of the ten critical ‘planetary boundaries’ of the Earth system [14], will be subsequently transported to aerosol-borne P and rapidly deposited in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Thus, the largest reservoirs of P in soil and marine environment are phosphate rock (PR) and sedimentary rock, respectively. The natural P cycle is a simple one-way flow from terrestrial to aquatic ecosystems through inorganic PR denudation and sediment immobilization on medium-term timescales (103 years) [8][15].

Previous studies have considered biological activity, human perturbation, and climate change as important factors impacting global P cycling by increasing P concentrations from both external and internal sources, with consequences for terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems [6][8][16][17][18]. Human activities, including the development and utilization of organophosphorus chemicals, extraction of geological P reserves to produce P–fertilizers, and the disposal of animal excreta into the environment, have dramatically impaired soil P geochemical balances and ecosystem functions [19][20][21][22]. Both precipitation and soil temperature have contrasting effects on P availability and control the soil P cycle through interactions with soil particles [23]. Hence, environmental factors involved in soil P geochemical reactions or affecting P-containing compounds can definitely influence the soil P cycle. Although the soil carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) cycles have received considerable attention, much less is known about the change in the P cycle and P availability in response of biological activities and climate change [23].

Phosphate solubilizing microorganisms (PSMs), a large microflora that mediate bioavailable soil P, play a critical role in the soil P cycle by mineralizing organic P, solubilizing inorganic P minerals, and storing large amounts of P in biomass [24][25]. By releasing phosphatase enzymes and organic acids, reducing soil pH, and increasing chelation activities with additional P adsorption sites, PSMs can dissolve soil P into soluble and plant available orthophosphate forms (mostly PO43–, HPO42–, and H2PO4–) [1]. Therefore, distinguishing the contributions of PSMs to plant nutrition acquisition, understanding the opportunities for manipulating PSMs to enhance soil P availability with the aim of restoring other soil elements, and improving soil health have received considerable interest [1][26]. Although inoculation with PSMs is a widely accepted environmentally-friendly approach for increasing soil soluble P concentrations and agricultural productivity, a comprehensive and complete understanding about the roles of PSM in P geochemical processes (i.e., dissolution–precipitation, sorption–desorption, and weathering) has not received the merited attentions [27]. In addition, the efficient utilization of PSMs in situ remains in its infancy as the wide-ranging applicability and potential eco-toxicity has not yet been demonstrated. In this review, we discuss the basic P forms and P cycling in the soil, how PSMs mediate soil orthophosphate levels, and the biogenic mechanisms behind these activities. Finally, we highlight the roles of PSMs in each P biogeochemical process, and propose environmental issues to prioritize in future PSM applications.

2. Basic P Forms and P Cycling in the Soil

Soil Po, which contributes a large proportion of total soil P, originates mainly from biological tissues where P is present as an integral part of organic compounds, such as nucleotides, phospholipids, phosphoproteins, and co-enzymes [1][30]. Soil nutrient cycling processes (e.g., nitrogen cycling) are also responsible for the re-distribution of primary Pi into Po forms over timescales of 104–106 years [30]. The widespread application of Po-containing products, such as plasticizers, fire retardants, antifoam agents, and pesticides, has resulted in their frequent occurrence in the environment as new Po sources, consequently increasing the quantities and varieties of Po forms in soils [31][32][33].

Unlike Po, which is more easily leached because of weak interactions with the soil particles [34], soil Pi is usually present as relatively insoluble and stable forms of primary (including apatite, strengite, and variscite) and secondary (including calcium, iron, and aluminum phosphates) P minerals [35][36][37][38]. Early studies developed chemical fractionation schemes to determine the fractions of Pi as (i) acid-extractable calcium-bonded P (including apatite and lattice-P), (ii) non–occluded P (including NH4F and NH4Cl extractable P, and 1st NaOH extractable P), and (iii) occluded P (including 2nd NaOH extractable P and residual Pi) [39][40]. The P ions in non-occluded P are adsorbed at the surfaces of Fe and Al oxides and are more easily extracted by NaOH than occluded P, in which P is incorporated within developing Fe and Al oxide coatings and concretions during diffusive penetration and soil development [39]. Pi concentrations also decrease as a function of soil development, ranging from an average of 684 µg /g soil in Entisols, to between 200 and 430 µg/g soil in Ultisols and Oxisols [29].

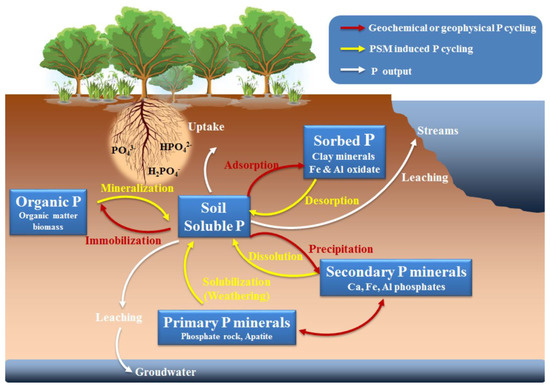

Pi exists in different forms and proportions in soil, which may leach into streams to deposit P in ocean sediments, or be taken up by plants or soil microorganisms in the secondary Po cycle [41]. After mineralization by plant structures (e.g., roots, stems, leaves), dead soil animals, and microorganisms, a large share of the assimilated Po returns to soils [42]. Even though P has a number of indispensable biochemical roles in the soil, it does not have rapid cycles compared with those of C, N, and S, which are transported not only in soil and water but also in the atmosphere [42][43]. In most natural ecosystems, geochemical processes, including weathering, adsorption/desorption, precipitation/dissolution, and solid–phase transformations (Figure 1), determine the forms (available or unavailable to plants) and distribution of P in soils over long-term timescales (> 103 years) [23]. However, in the short-term (10–2 to 100 years), biological processes influence P distribution because most of the plant-available P derived from soil organic matter is immobilized and mineralized by soil microbes [2][29]. While the effects of geochemical processes in controlling soil P availability are rather well understood, much about the importance of biological processes remains unknown [2].

3. PSM Enhance Soil P Cycle through Organic P Mineralization

Soil Po, which derives mainly from biomolecules, including nucleotides, phosphides, co-enzymes, phosphoproteins, sugar phosphates, and phosphonates, plays an essential role in soil P cycling [2][3][4]. Po substances (e.g., orthophosphate esters, phosphonates, and polyphosphates) are mostly short-lived compounds, and may comprise as much as 65% of Pt in most soils [31][44]. Based on its sources, soil Po can be considered to exist in a rapidly cycling pool (fast Po) and a slowly cycling pool (slow Po) [44]. The fast pool consists of the constant Po from soil solution immobilized in microbial biomass and resupplies the slow pool following cell death. Soil soluble orthophosphate ions can be immobilized in microbial cells to improve biomass growth. It is found that most of the P mineralized from organic P by PSM is incorporated into the bacterial cells as cellular P [45]. Concurrently, these soil microbes can rapidly release Po to the slow pool following cell lysis, cell death, and soil fauna predation [44][46]. Plant detritus, dead animals and microbes, and non-living Po fertilizers (e.g., dry straw and animal manure) are the most common slow Po sources that can directly replenish soil orthophosphate contents through geochemical or biological decomposition, beneficial for plant-available P supplies and soil quality improvement (Figure 1) [47][48][49]. Hence, manipulation of the orthophosphate release from soil Po sources is an important soil P cycle, which has the potential to increase the availability of soil Po for plant uptake and reduce reliance on the P fertilizer inputs. Soil microbes, especially PSM, can enhance soil Po cycle through Po mineralization and decomposition. By analyzing soil P pools and oxygen isotope ratios in P (δ18OP), Bi et al. [50] have uncovered that soil microbes could activate the soil P cycle by promoting extracellular hydrolysis of Po compounds and facilitating the turnover of bioavailable P pools (H2O-Pi, NaHCO3-Pi, and NaOH-Pi). These biogeochemical processes are mainly moderated by the activities of phosphatase enzymes in PSM and soils [48].

PSMs isolated from bulk soils and rhizospheres have been shown to hydrolyze Po by the release of phosphatases [50]. Phosphatases are enzymes responsible for Po decomposition and mineralization by catalyzing the hydrolysis of both esters and anhydrides of phosphoric acid, and they are usually classified as phosphomonoesterases, phosphodiesterases, and enzymes acting on phosphoryl–containing anhydrides or on P–N bonds [51]. These enzymes originate mainly from soil microorganisms and plant cells, and the enzyme activities are always higher in rhizosphere than in bulk soil [47]. The Po hydrolysis activities of extracellular phosphatase enzymes are affected by soil properties, microbial interactions, plant cover, and environmental inhibitors and activators [51]. Some key environmental traits associated with phosphatase enzyme activities can be genetically manipulated by the regulation of P-cycling-related genes in PSMs and other microorganisms under P deficiency conditions [26][52]. Although soil PSM is involved in Po mineralization and P cycle at various scales, the dominant enzymes and the functional genes are always similar. It has been established that the dynamics of microbial genes and expression of phosphatase enzymes are the key factors governing mineralization of Po into bioavailable orthophosphates by PSMs [50].

The non-specific acid phosphatases (phosphohydrolases, or NSAPs) released by PSMs perform dephosphorylation of phosphodiester or phosphoanhydride bonds in Po matters, and they play a major role in Po mineralization in most soils [53]. These NSAPs may be either acid or alkaline phosphomonoesterases [54], and several NSAP genes have been isolated and characterized in PSMs [53]. For example, olpA gene of Chryseobacterium meningosepticum encodes and expresses a broad–spectrum of phosphatases that efficiently hydrolyze monophosphates and sugar phosphates [55]. PhoN and PhoK from indigenous soil PSMs could express periplasmic acid phosphatase and extracellular alkaline phosphatase, in genetically modified Deinococcus radiodurans and Escherichia coli, respectively, to enhance the biomineralization of toxic ions in polluted soil [56]. Cyanobacterial Microcystis aeruginosa harbors genes encoding extracellular alkaline phosphatase to utilize a variety of inorganic or organic insoluble P [57][58]. Phytase enzyme, encoded by appA or phyA genes, is another important Po mineralization enzyme responsible for P release from phytate in soil [54]. Previous studies have focused on applications of phytase in the Po mineralization as phytate is the major component of Po forms in soil [53]. Approximately 30–48% of culturable soil microorganisms were reported to utilize phytate by producing phytase enzyme [59]. Yeasts (including Pichia acacia and Candida argentea) were also demonstrated to produce phytase and utilize phytic acid as their sole P source [60], while a great diversity of phytase exists in the vast majority of unculturable soil microorganisms, which have been rarely studied. Using metagenomics, Farias et al. [61] constructed environmental genomic libraries to determine the complete sequencing of the clone phytase gene from unculturable soil microorganisms in red rice crop residues and castor bean cake. The newly isolated phytase enzyme showed high hydrolase activity at neutral pH under β-propeller structure. Therefore, it is crucial to develop and utilize more advanced approaches to support the roles of PSM–derived enzymes in releasing free orthophosphate from organic P forms in the soil P cycle [25][54][59][62].

4. PSM-Mediated Inorganic P Solubilization to Enhance Soil Orthophosphate Contents

Pi is an essential but non-renewable resource for plants on Earth. As plant-available Pi comes mainly from the soil environment, increasing global food demand has substantially increased the use of PR for the production of P fertilizer [63]. Previous studies have shown that the peak of global PR mining is estimated to occur in 2030, and the global Pi mine will be exhausted in the next 50 to 100 years [7][64]. The types of Pi in PR and other primary Pi minerals are insoluble and unavailable to most plants. In addition, modern agricultural consumption of PR and Pi fertilizers can lead to excessive accumulation of soil P in intensively managed croplands, resulting in P losses and eutrophication of surface waters [65]. Thus, sustainable and judicious PR mining management strategies to reduce water pollution and eutrophication problems have attracted worldwide attention [7]. From the last century to the present, researchers have proved that the application of PSMs is an accepted solution for successful PR mining management and agricultural sustainability [66][67][68][69].

In early studies, PSMs are defined as microbes that transform insoluble Pi and Po to soluble P forms and regulate biogeochemical P cycling in agroecosystems [70][71]. Among heterogeneously distributed soil microflora, a large number of heterotrophic and autotrophic microorganisms, including phosphate solubilizing bacteria (PSB), phosphate solubilizing fungi (PSF), phosphate solubilizing actinomycetes (PSA), and cyanobacteria are commonly identified as PSM [65][72]. PSB, such as Bacillus sp., Pseudomonas sp., Rhizobium sp., and Escherichia sp., form the largest microbial communities with P solubilization abilities in soil. PSF have greater Pi solubilizing abilities than PSB by attaching Pi minerals to increase the contact area in liquid medium [73]. Penicillium sp., Aspergillus sp., Mucor sp., and Rhizopus sp. are the commonly isolated and demonstrated PSF microflora in soil. Some previous studies have found that several arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), such as Rhizophagus irregularis [74], Glomus aggregatum, and Glomus mosseae [75], can also solubilize Pi either directly through exudation, or indirectly through modification of soil PSM communities [74]. Owing to their dominance and strong antimicrobial potential, filamentous actinobacteria have been extensively used for colonizing plant tissue and producing antibiotics, anti–fungal, and phytohormone-like products that can be beneficial to plant growth [62][76][77][78]. Moreover, actinobacteria, especially Streptomyces and Micromonospora, are of increasing interest since these sporulating bacteria are capable to solubilize insoluble P minerals in Pi weathering process and the soil P cycle [78][79][80]. In addition to these common heterotrophic PSM, autotrophic microorganisms with Pi solubilizing abilities were also reported [65]. Yandigeri [81] evaluated the rock phosphate and tricalcium phosphate solubilizing abilities of two diazotrophic cyanobacteria, Westiellopsis prolifica, and Anabaena variabilis. Periodic monitoring showed that both cyanobacterial strains could significantly increase Pt and available-P contents in medium in P-starved or insoluble-P cultures.

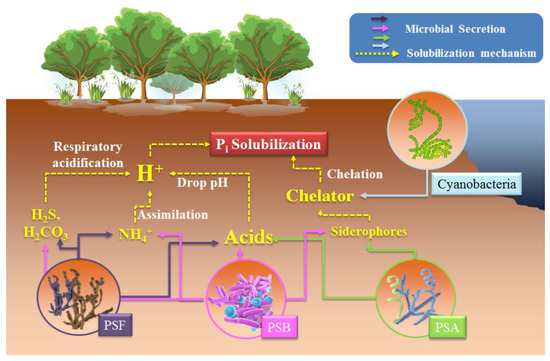

PSMs, including PSB, PSF, and PSA, can transform insoluble Pi to soluble orthophosphate forms (PO43–, HPO42–, and H2PO4–) by secreting various organic or inorganic acids that release H+ and lower the medium pH [27][72] (Figure 2). Moderately labile Pi (Pi partly from Fe/Al–P and from the surface of sesquioxides) can become accessible to soil organisms through organic acid excretion by PSMs which, in turn, chelate Fe and Al ions so that P is liberated [82]. The carboxyl groups of organic acids can bind P by replacing cations or compete for P adsorption sites, enhancing the soil absorption of PO43– and increasing Pi solubilization. Notable levels of organic acid production and Pi solubilization performance are achieved by PSM isolates [83]. Although PSB represent the largest PSM population in soil environment, PSF exhibit greater Pi solubilization abilities by producing 10 times more organic acids than PSB, declining pH by 1–2 units in both liquid and solid media [73]. Furthermore, different Pi minerals show a range of H+ production and Pi solubility levels, which can be explained based on Ksp values, acidity coefficients, and chemical equilibria [83]. Under strong acid conditions, PO34− will be dissolved first from Pi minerals and protonated to form hydrogen P (HPO42− or H2PO4−). Metal ions (e.g., Ca2+, Fe3+, or Al3+) are likely to subsequently capture the hydrogen P to form metal hydrogen P with generally higher Ksp values than their equivalent metal P [84]. Hence, Pi minerals can almost completely dissolve under strongly acidic conditions. For example, the majority of Ca3(PO4)2 solubilization occurs in the pH range of 2.5 to 4.0, while FePO4 solubilization occurrs from 2.0 to 2.5 [73]. Accordingly, this explains the lower Pi solubilization efficiencies obtained with monocarboxylic acids (acetic, formic, lactic, and gluconic acids) compared to di- and tri-carboxylic acids (oxalic, malic, and citric acids), which have higher acidity coefficients [73][84].

H+ may originate from other biotic phenomena, for example from H2S and H2CO3 respiratory acidification (Figure 2), but these acidification processes cannot be responsible for all Pi solubilization. Instead, the total solubilization of apatite and brushite were observed in H+ production accompanying NH4+ assimilation in Pseudomonas sp. and Penicillium sp. [85]. Exopolysaccharides (EPS), important polymers consisting mainly of carbohydrates, were suggested as an important factor in Pi solubilization by PSB [27]. EPS could disturb the homeostasis of organic acids or H+ involved in Pi solubilization process by holding free P in the medium, consequently resulting in more P release from Pi minerals [86]. However, further studies are required to understand the mechanisms of synergistic Pi solubilization by organic acids and EPS.

Actinobacteria and Cyanobacteria have rarely been reported for production and quantification of organic acids in Pi solubilization [76][79]. Streptomyces sp. were isolated from wheat rhizospheric soil and demonstrated to solubilize Ca3(PO4)2 and PR by malic and gluconic acid secretion in glucose-supplemented medium [76]. PSAs of Streptomyces sp. and Micromonospora sp. were previously reported to solubilize PR by producing Ca-chelators or siderophores [78]. In addition to organic acid secretion and H+ dissolving mechanisms, P may be liberated from Pi minerals by the synthesis of chelators (e.g., Ca, Al, and Fe-chelators) in PSB, PSA, and blue green algae (Figure 2) [78][81][87][88]. Since PR and other primary Pi minerals are mainly insoluble hydroxyapatite, or Ca, Al, and Fe/phosphate, the siderophores and chelators could form chelates with Ca, Al, and Fe, resulting in the release of P originally bound by these metals [81].

5. PSM-Derived P Desorption from Clay Minerals

Soluble P forms are easily fixed and removed from soil solution by adsorption reactions and incorporated into the solid phase. These chemical reactions are particularly strong on the surfaces of amorphous iron (Fe) and aluminum (Al) (hydr)oxides in highly weathered tropical and volcanic ash soils (Figure 1) [89][90]. Fe and Al (hydr)oxides are the most important variable-charge minerals with higher P adsorption capacity and binding energy compared with permanent-charge minerals [91]. After long–term fertilization, most soil P is absorbed to Al (hydr)oxides, whereas, in unfertilized soils, P absorbed on Fe is the dominant P species in clay minerals [92]. The strong correlation between Fe (Al) and orthophosphate produces as Fe–P (Al–P) hydroxides with a high capacity of sorption that results in soil P deposition [93][94]. In addition, soil organic matters can also absorb or immobilize orthophosphate into relatively stable Po compounds and reduce dissolved P concentrations [95].

Indigenous soil microorganisms with P solubilization abilities were identified to desorb P from the surfaces of clay minerals and soil organic matter [89]. He and Zhu [91] reported that microbial transformation and desorption of P from the surfaces of variable charge–minerals, including Fe and Al (hydr)oxides, predominates in Chinese red soils. Seventeen to thirty-four percent of clay mineral-absorbed P are transformed and desorbed to water-soluble and plant-available P by microbes. As the capacity of PSM to desorb P depends on the Pi-adsorption capacity, surface areas of clay minerals, and the saturation of Pi-absorbing sites, the effectiveness of Mortiella sp. to desorb P is ranked as montmorillonite > kaolinite > goethite > allophane [90]. Furthermore, inoculation with Mortiella sp. can significantly increase in situ soil Pi solution through desorption, and the efficiency is enhanced by increasing the absorbed Pi levels in different soils. It can be concluded that the capacity of PSM to augment soil soluble Pi is directly related to the quantity of P absorbed by soil and clay minerals, while the magnitude of Pi desorption by PSM is inversely correlated with the Pi-sorption capacities of soil and clay minerals [96].

The phenomenon of P desorption by PSM usually occurs along with the drop of pH. It is presumed that P desorption may result from the increased solubility of Fe and Al by the possible complexation with low molecular weight organic acids [91][97]. Plant roots and PSM could release various low molecular weight organic acids, such as citrate, oxalate, and malate, during Pi mineral solubilization processes, and these organic acids are widely recognized to enhance Pi availability in soils through desorption [44][90][97]. Organic acids and anions can displace Pi from absorbing sites through ligand exchange from microbial activities and transitory blockage of Pi adsorption sites [98]. Depending on their dissociation properties and carboxylic groups, organic acids can carry varying negative charges to increase the desorption of Pi [97]. For example, the effectiveness of organic acids in reducing Pi sorption follows the order tricarboxylic > dicarboxylic > monocarboxylic acid, which is explained by the constant of complex formation values [96]. Oburger [99] found that the adsorption and desorption isotherms of organic acids could be described by the Freundlich equation and the dynamic sorption model. This model succeeds in both predicting the solid solution partitioning of citrate in soils and demonstrating the plateau and steady state concentrations of citrate in solution, highlighting the key effects of organic acid dynamics on the Pi adsorption-desorption reactions and the functional roles of PSM in soil [98][100].

6. PSM-Induced Dissolution in Accelerating Metal Precipitation to form Secondary Pi Minerals

Insoluble Pi in soils is always constrained by the presence of Ca, Fe, Al, or heavy metal cations [84]. Generally, in acidic soils, P ions tend to precipitate with Fe and Al cations to form insoluble oxyhydroxides or secondary Pi minerals. In alkaline soils, P ions mainly precipitate with Ca to form secondary Pi minerals, such as fluroapatite, hydroxyapatite, and chloroapatite [101][102][103]. Thus, the geochemical precipitation of P in soil and wastewater have contrasting effects on physicochemical stabilization of organic P compounds and environmental control of Pi levels [44][104][105].

The apatite families, including Ca–phosphate apatites (Ca5(PO4)3X, where X = Cl, OH, or F) and strontium–phosphate apatite (Sr5(PO4)3H), are environmentally important secondary minerals [106][107]. PSMs can accelerate apatite formation by the release of Pi and the hydrolysis of Po with alkaline phosphataes [108]. An oxygen isotope tracing method reveals that a metastable apatite precursor is initially precipitated and then transforms to hydroxy apatite on the surface of microbial filaments, suggesting that the apatite precipitation process involves extensive biological turnover of Pi by microorganisms [109]. Fe–P minerals are effectively precipitated and formed by orthophosphate ions and goethite (α–FeO(OH)), the most common secondary Fe oxyhydroxide in natural environments, through monodentate- or bidentate-complexing process [101]. Accordingly, precipitated Fe–P minerals, including vivianite, strengite, and ferrihydrite, are demonstrated as effective and promising approach to improve P removal and recovery [110]. These precipitated P minerals can release P in soil upon dissolution, the processes of which are enhanced by soil PSMs.

Among Ca–P secondary minerals, hydroxyapatite is a common P source for soil microorganisms and is often utilized to isolate PSMs accompanied by Ca3(PO4)2 and apatite [111][112]. This crystallized Ca–P mineral is much more dissolution–resistant than amorphous Ca3(PO4)2, and hydroxyapatite dissolution is driven by the microbial production of D–gluconic and 2–keto–D–gluconic acids, which were more effective than Pi desorption from Fe oxyhydroxide [101]. Fe–P and Al–P minerals also commonly exist as plant P sources in soil. These secondary minerals show relatively higher pKsp and lower dissolution rates than Ca–P minerals [85][113], and the dissolution mechanisms are characterized as plant- or PSM-mediated organic acid release (such as citric and piscidic acids that have high acidity coefficients) [114] and iron–binding siderophore production [115].

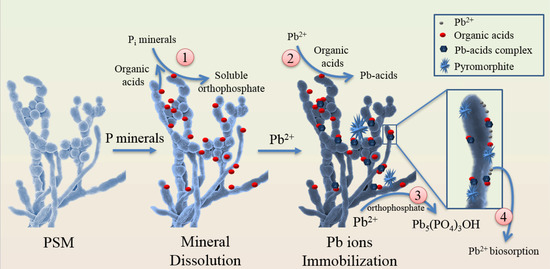

Research has focused increasingly on biomineralization of heavy metals to form stable precipitations or secondary Pi minerals in soil [116][117][118][119]. Biomineralization based microbial induced phosphate precipitation (MIPP) is a novel approach for soil heavy metal remediation. By adding exogenous P sources, indigenous PSMs can release various organic acids and phosphatases to increase soluble orthophosphate concentrations, which then mediate metals ions mineralization as P–containing minerals [56]. Many toxic heavy metals including Pb, U, Zn, Cu, and Cd are reportedly immobilized as stable P–containing minerals through MIPP processes [120]. Among them, Pb is the most frequently reported heavy metal that can be precipitated by MIPP (Figure 3). Pb ions can be immobilized by cell surface biosorption, organic acid-mediated precipitation, and P-containing mineralization [117][121]. These P-containing minerals include Pb3(PO4)2, Pb9(PO4)6, lead apatite (Ca(10–x)Pbx(PO4)6(OH)2), and pyromorphite family (Pb5(PO4)3X, X = Cl–, OH–, Br–, F–, Ksp = 10–71.6 ~10–84.4), considered as the most stable precipitated Pb minerals in the environment [56][117][122].

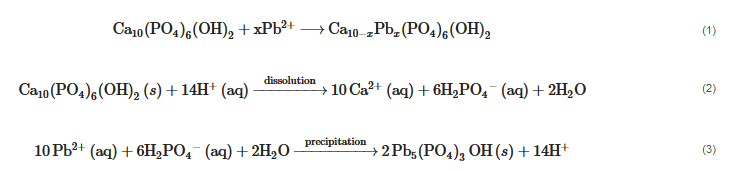

In the presence of Pi minerals (such as apatite and PR), Pb2+ can replace Ca2+ by ion exchange to form lead apatite (Equation (1)), or be absorbed to form Ca8Pb2(PO4)6(OH)2 [123]. In the presence of both Pi minerals and PSM, hydroxypyromorphite precipitation includes the reaction of Pb2+ with apatite through PSM–induced hydroxyapatite dissolution as shown in Equations (2) and (3) [119].

PSBs Pabtoea ananatis and Bacillus thuringiensis can effectively solubilize PR to release soluble P, which rapidly reacts with Pb2+ to form insoluble lead minerals, and reduces the phytoavailability of Pb2+ to benefit plant grwoth and net photosynthetic rate [124]. Zhang [118] found that the Pb3(PO4)2 and Pb5(PO4)3OH precipitates produced by PSBs decomposing organophosphorus polymers were more stable than those of urease-producing bacteria that produce PbCO3. Furthermore, other toxic metals, such as U, Cu, Zn, Cd, and Ni, have also been reported to be bioimmobilized by MIPP. For example, U could react with PSM–released orthophosphate to precipitate numerous U–P minerals, such as chernikovite (H2(UO2)2(PO4)2), autunite (Ca(UO2)2(PO4)2), uramphite (NH4(UO2)2(PO4)3H2O), and ankoleite (K2(UO2)2(PO4)2) [56]. PSA Streptomyces showed high heavy metal resistance and mineralization properties to form crystallized P–containing switzerite (Mn3(PO4)2•7H2O) and hydrated nickel hydrogen phosphate [125]. Therefore, PSM-induced Pi mineral dissolution can both supply bioavailable orthophosphate to plants and accelerate metal precipitation to form secondary P-containing minerals in soil.

7. Effect of PSM on Pi Mineral Weathering and the Biogeochemical P Cycle

Chemical or biological weathering of primary P minerals has substantial influence on the global biogeochemical P cycle [36][126][127]. Continental weathering of P minerals provides the ultimate source of bioavailable P to marine systems and supplies almost the entire source of P in most soil profiles [128]. Globally-enhanced continental weathering has delivered vast amounts of P to the oceans, resulting in the increased levels of subsequent eutrophication and marine anoxia [12][36]. The weathering of P minerals depends on numerous environmental factors, including earth history, environmental erosion, atmospheric composition, rock P contents, soil microaggregate fractions, and biological response [15][36][126][129][130][131]. As soil microorganisms with Pi mineral weathering abilities, PSM or phosphate-dissolving microorganisms, are environmentally widespread [111][132]. These microorganisms can release orthophosphate from amorphous Pi minerals, such as Ca3(PO4)2, FePO4, P–bearing mineral powders, and crystalline Pi minerals, such as apatite, fluorapatite, and phosphorites, mainly through acidolysis [111][132][133][134]. PSM Pseudomonas fluorescens can dissolve fluorapatite as its sole P source to release P, Ca, and F in acidified medium, which is important in the weathering of fluorine-bearing minerals [132]. Several unfamiliar PSMs, along with Micromonospora sp. and Streptomyces sp., are found to produce siderophores but not organic acids during PR weathering processes [135]. PSMs with thermo-tolerance and drought tolerance abilities are able to release large amounts of other useful minerals, such as K, Mg, Fe, and F, by weathering P minerals, fluorapatite, extrusive igneous rock and limestone [132][136]. Therefore, the net effects of PSMs on Pi mineral weathering are similar to those of Pi mineral solubilization, resulting in accelerated dissolution of primary Pi minerals to release P and laterally transporting P in soil systems.

8. PSM Enhance P Uptake from Soil to Plant in the Rhizosphere Environment

Bioavailable P content in soil is an important factor to enhance plant P uptake and achieve higher crop yields [72][137]. Soil PSM can employ different biogeochemical strategies to make use of the unavailable P forms and in turn help in enhancing P uptake from soil to plants. Hence, most studies have considered PSM as a promising inoculant/biofertilizer for raising the productivity of agronomic crops in agroecological niches [72][137][138]. However, the soil is a more diverse and spatially heterogeneous matrix than a growth medium, which will result in some of the discrepancies between the in vitro and in vivo potential of PSM to improve plant nutrition and growth [139]. The PSM-mediated bioavailable P is not utilized directly by plant or soil microbes; instead, it is quickly subject to precipitation or adsorption reactions in the immediate vicinity in which it is solubilized or desorbed by PSM [140]. Additionally, the P solubilization of exogenous PSM may be reduced due to the lack of persistence by competition with endogenous microbes for P resources, or by maladjustment of newly inoculated soil environment [141][142]. Hence, the PSM-enhanced P uptake from soil to plant likely occurs in the rhizosphere environment, which provides higher growth potential for PSM than bulk soils [74][142].

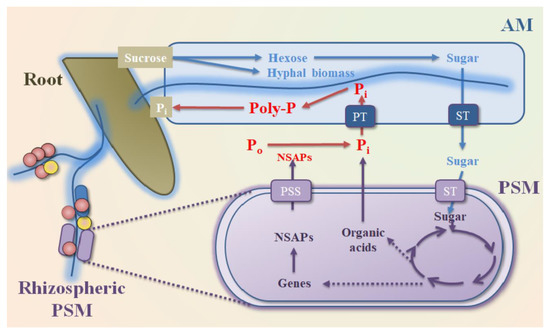

Rhizosphere PSMs, which are commonly considered as symbiotic or free–living microorganisms, are capable of colonizing rhizospheric plant roots, improving plant stress tolerance to drought, salinity, and heavy metals, and increasing the rhizospheric orthophosphate contents by inorganic or organic P solubilization [143][144][145]. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are the most common symbiont to increase P uptake capacity of plants [146]. Plants in symbiosis with AMF through formation of dense “cluster roots” can produce organic anions or H+ to release Pi from P minerals, enhancing soil Pi uptake by AMF and plants. The concentration of bioavailable Pi ions (e.g., H2PO4–) in plants and AMF cells can reach about 1000-fold higher than in the soil solution [147]. Using a compartmented pot system with an isotope 33P labeled pool dilution, the P uptake performance of wheat was significantly improved by high levels of AMF Rhizophagus irregularis colonization from soluble P, dried sewage sludge, and incinerated sewage sludge [74]. Moreover, AMF can enhance plant P uptake by recruiting and enriching beneficial microbes, including soil PSM, in the extensive hyphae under nutrient-scarce conditions, and thus provide a wider physical exploration of P undepleted soil [148].

Nevertheless, the ability of AMF to acquire P from the soil Po pool may depend on the reactions with rhizospheric PSM because several AMF lack NSAPs genes [149]. Hence, the beneficial interactions between AMF and PSM occur by providing key resources for each other [150]. AMF can extend hyphae and transform PSM to the Po pool. The exudates (e.g., sugars, carboxylates, amino acids) released by AMF or plants then stimulate the growth of rhizospheric PSM, and further improve the Po mineralization, which, in turn, gives positive effects on the uptake of P by AMF and plants (Figure 4) [151]. A similar study found that the fructose excreted by AMF Rhizophagus irregularis stimulated the expression of phosphatase genes in PSB Rahnella aquatilis. Meanwhile, the fructose stimulated the release rate of phosphatase by regulating the protein secretary system (Figure 4), promoting the Pi release from Po mineralization and the subsequent Pi uptake by AMF [152]. Using metagenomics and amplicon sequencing, increasing microbial communities with P solubilizing abilities and soil P cycling potentials are found in the hyphae-associated communities, also suggesting that AMF can recruit rhizospheric PSM to transfer P-containing nutrients from AMF hyphae to their symbiotic plants and enhance the P uptake from soil to plants [153][154].

9. Conclusions and Future Prospects

PSMs have gained wide acceptance as environmentally friendly and easily acquired P fertilizers to improve soil orthophosphate concentrations and P geochemical cycles since the beginning of the 20th century. A considerable number of PSMs with Po or Pi solubilizing characteristics have been isolated, with selected ones used in plant growth and soil trails. These PSMs are highly abundant in soil and definitely have important roles in the global biogeochemistry of soil P cycling, including mineralization, solubilization, desorption, dissolution, and weathering. However, large scale in situ field tests are still urgently required. Previous studies have discussed improvements in plant growth, such as biomass increase, rhizosphere expansion, and physiological properties, while changes are usually ignored in important intermediates or metabolites of plants and PSMs, plant signal transductions, P morphological variations, and plant-microbe interactions during Po or Pi solubilization processes in the rhizosphere. For example, although AMF are obligate biotrophs that compensate the host plants through nutrient acquisition and produce extensive extraradical hyphae as habitat for other soil microbes, they can only utilize Po and improve plant P uptake in symbiosis with PSMs, as they lack the ability to secrete phosphatases [150][152]. Unfortunately, the relative contribution of PSMs to the acquisition of P in this symbiotic relationship remains largely unknown.

P cycling in soil depends on a combination of physical, chemical, and biological processes. Inoculation with PSM—which are always non-indigenous—as P fertilizers, may be considered a biological intervention or anthropogenic perturbation affecting the soil P cycle and native microbial community structure. It is a great hurdle to characterize the growth and the functions of PSM in soil. Recent studies have introduced some novel approaches (e.g., isotope labeling, metagenomics) to discuss the resistance of inoculated PSMs and their roles in soil P cycle [155]. Liang et al. [25] found that previously unknown PSB isolates were capable of solubilizing Po and played important roles in driving the enhancement of soil P cycle using metagenomic sequencing. Hong et al. recently pointed out Raman spectroscopy as a promising tool for identifying microbial phenotypic and functional heterogeneity at the single-cell level without destroying the original cells or samples. Li et al. [156] applied single-cell Raman spectroscopy coupled with D2O labeling to probing Po and Pi solubilizing bacteria, which discerned and located PSB in a mixed bacterial medium and complex soil communities at the single-cell level. These approaches may give us more novel options to understand the ecological functions and risks of PSM inoculation in soil P migration behavior, spatiotemporal variation characteristics of biologically available P, and soil indigenous microbial communities. In addition, studies on spatiotemporal changes in soil P dynamics and the relative rates of C and N erosion are required to improve our understanding of the roles of PSMs in the soil P cycle, and to develop some conceptual C and N biogeochemistry models for dynamic landscapes [129][131]. Based on the contribution of PSMs to global P cycling, there are important ecological, biogeochemical, and financial reasons to improve our understanding on PSM abilities and their utilization potentials in agricultural development.

References

- Billah, M.; Khan, M.; Bano, A.; Hassan, T.U.; Munir, A.; Gurmani, A.R. Phosphorus and phosphate solubilizing bacteria: Keys for sustainable agriculture. Geomicrobiol. J. 2019, 36, 904–916.

- Tamburini, F.; Pfahler, V.; Bunemann, E.K.; Guelland, K.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Frossard, E. Oxygen isotopes unravel the role of microorganisms in phosphate cycling in soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 5956–5962.

- Tate, K.R. The biological transformation of P in soil. Plant Soil 1984, 76, 245–256.

- Westheimer, F.H. Why nature chose phosphates. Science 1987, 235, 1173–1178.

- Ma, Y.; Prasad, M.N.; Rajkumar, M.; Freitas, H. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and endophytes accelerate phytoremediation of metalliferous soils. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 248–258.

- Onodera, S.; Okuda, N.; Ban, S.H.; Saito, M.; Paytan, A.; Iwata, T. Phosphorus cycling in watersheds: From limnology to environmental science. Limnology 2020, 21, 327–328.

- Xiong, C.; Guo, Z.; Chen, S.S.; Gao, Q.; Kishe, M.A.; Shen, Q. Understanding the pathway of phosphorus metabolism in urban household consumption system: A case study of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274.

- Liu, X.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, H.; Jiang, S. Historic Trends and Future Prospects of Waste Generation and Recycling in China’s Phosphorus Cycle. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 5131–5139.

- Lu, G.Y.; Song, X.X.; Yu, Z.M.; Cao, X.H. Application of PAC-modified kaolin to mitigate Prorocentrum donghaiense: Effects on cell removal and phosphorus cycling in a laboratory setting. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 917–928.

- McMahon, K.D.; Read, E.K. Microbial Contributions to Phosphorus Cycling in Eutrophic Lakes and Wastewater. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 67, 199–219.

- Falkowski, P.G.; Fenchel, T.; Delong, E.F. The microbial engines that drive Earth’s biogeochemical cycles. Science 2008, 320, 1034–1039.

- Percival, L.M.E.; Bond, D.P.G.; Rakocinski, M.; Marynowski, L.; Hood, A.V.S.; Adatte, T.; Spangenberg, J.E.; Follmi, K.B. Phosphorus-cycle disturbances during the Late Devonian anoxic events. Global Planet Change 2020, 184, 103070.

- Nguyen, T.B.; Lee, P.B.; Updyke, K.M.; Bones, D.L.; Laskin, J.; Laskin, A.; Nizkorodov, S.A. Formation of nitrogen- and sulfur-containing light-absorbing compounds accelerated by evaporation of water from secondary organic aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012, 117.

- Wang, R.; Balkanski, Y.; Boucher, O.; Ciais, P.; Penuelas, J.; Tao, S. Significant contribution of combustion-related emissions to the atmospheric phosphorus budget. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 48–54.

- Laakso, T.A.; Sperling, E.A.; Johnston, D.T.; Knoll, A.H. Ediacaran reorganization of the marine phosphorus cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11961–11967.

- Yuan, Z.; Jiang, S.; Sheng, H.; Liu, X.; Hua, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. Human Perturbation of the Global Phosphorus Cycle: Changes and Consequences. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2438–2450.

- Chapuis-Lardy, L.; Le Bayon, R.-C.; Brossard, M.; López-Hernández, D.; Blanchart, E. Role of Soil Macrofauna in Phosphorus Cycling. In Phosphorus in Action; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 199–213.

- Mooshammer, M.; Hofhansl, F.; Frank, A.H.; Wanek, W.; Hammerle, I.; Leitner, S.; Schnecker, J.; Wild, B.; Watzka, M.; Keiblinger, K.M.; et al. Decoupling of microbial carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling in response to extreme temperature events. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1602781.

- Cordell, D.; Drangert, J.-O.; White, S. The story of phosphorus: Global food security and food for thought. Global Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 292–305.

- Elser, J.; Bennett, E. Phosphorus cycle A broken biogeochemical cycle. Nature 2011, 478, 29–31.

- Hébert, M.-P.; Fugère, V.; Gonzalez, A. The overlooked impact of rising glyphosate use on phosphorus loading in agricultural watersheds. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 48–56.

- Liu, X.; Sheng, H.; Jiang, S.Y.; Yuan, Z.W.; Zhang, C.S.; Elser, J.J. Intensification of phosphorus cycling in China since the 1600s. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2609–2614.

- Hou, E.; Chen, C.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, G.; Kuang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Heenan, M.; Lu, X.; Wen, D. Effects of climate on soil phosphorus cycle and availability in natural terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 3344–3356.

- Gross, A.; Lin, Y.; Weber, P.K.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Silver, W.L. The role of soil redox conditions in microbial phosphorus cycling in humid tropical forests. Ecology 2020, 101, e02928.

- Liang, J.L.; Liu, J.; Jia, P.; Yang, T.T.; Zeng, Q.W.; Zhang, S.C.; Liao, B.; Shu, W.S.; Li, J.T. Novel phosphate-solubilizing bacteria enhance soil phosphorus cycling following ecological restoration of land degraded by mining. ISME J. 2020, 14, 1600–1613.

- Richardson, A.E.; Simpson, R.J. Soil Microorganisms Mediating Phosphorus Availability. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 989–996.

- Sharma, S.B.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Trivedi, M.H.; Gobi, T.A. Phosphate solubilizing microbes: Sustainable approach for managing phosphorus deficiency in agricultural soils. Springerplus 2013, 2, 587.

- Xu, X.L.; Mao, X.L.; Van Zwieten, L.; Niazi, N.K.; Lu, K.P.; Bolan, N.S.; Wang, H.L. Wetting-drying cycles during a rice-wheat crop rotation rapidly (im)mobilize recalcitrant soil phosphorus. J. Soils Sediment. 2020.

- Cross, A.F.; Schlesinger, W.H. A literature review and evaluation of the Hedley. Geoderma 1995, 64, 197–214.

- Adams, M.A.; Pate, J.S. Availability of organic and inorganic forms of phosphorus to lupins (Lupinus spp.). Plant Soil 1992, 145, 107–113.

- Fabianska, M.J.; Kozielska, B.; Konieczynski, J.; Bielaczyc, P. Occurrence of organic phosphates in particulate matter of the vehicle exhausts and outdoor environment—A case study. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 244, 351–360.

- Hoffman, K.; Butt, C.M.; Webster, T.F.; Preston, E.V.; Hammel, S.C.; Makey, C.; Lorenzo, A.M.; Cooper, E.M.; Carignan, C.; Meeker, J.D.; et al. Temporal Trends in Exposure to Organophosphate Flame Retardants in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2017, 4, 112–118.

- Wu, H.J.; Yuan, Z.W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Gao, L.M.; Liu, S.M. Life-cycle phosphorus use efficiency of the farming system in Anhui Province, Central China. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2014, 83, 1–14.

- Gebrim, F.D.; Novais, R.F.; da Siva, I.R.; Schulthais, F.; Vergutz, L.; Procopio, L.C.; Moreira, F.F.; de Jesus, G.L. Mobility of Inorganic and Organic Phosphorus Forms under Different Levels of Phosphate and Poultry Litter Fertilization in Soils. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo. 2010, 34, 1195–1205.

- Maltais-Landry, G.; Scow, K.; Brennan, E. Soil phosphorus mobilization in the rhizosphere of cover crops has little effect on phosphorus cycling in California agricultural soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 255–262.

- Hao, J.; Knoll, A.H.; Huang, F.; Schieber, J.; Hazen, R.M.; Daniel, I. Cycling phosphorus on the Archean Earth: Part II. Phosphorus limitation on primary production in Archean ecosystems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 280, 360–377.

- Prietzel, J.; Harrington, G.; Hausler, W.; Heister, K.; Werner, F.; Klysubun, W. Reference spectra of important adsorbed organic and inorganic phosphate binding forms for soil P speciation using synchrotron-based K-edge XANES spectroscopy. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 2016, 23, 532–544.

- Hesterberg, D.; Zhou, W.; Hutchison, K.J.; Beauchemin, S.; Syers, D.E. XAFS study of adsorbed and mineral forms of phosphate. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 1999, 6, 636–638.

- Walker, T.W.; Syers, J.K. The fate of phosphorus during pedogenesis. Geoderma 1976, 15, 1–19.

- Williams, J.D.H.; Syers, J.K.; Walker, T.W. Fractionation of soil inorganic phosphate by a modification of Chang and Jackson’s procedure. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1967, 31, 736–739.

- Mathew, D.; Gireeshkumar, T.R.; Balachandran, K.K.; Udayakrishnan, P.B.; Shameem, K.; Deepulal, P.M.; Nair, M.; Madhu, N.V.; Muraleedharan, K.R. Influence of hypoxia on phosphorus cycling in Alappuzha mud banks, southwest coast of India. Reg. Stud. Mar Sci. 2020, 34, 101083.

- Smil, V. Phosphorus in the Environment Natural Flows and Human Interferences. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2000, 25, 53–88.

- Anantharaman, K.; Brown, C.T.; Hug, L.A.; Sharon, I.; Castelle, C.J.; Probst, A.J.; Thomas, B.C.; Singh, A.; Wilkins, M.J.; Karaoz, U.; et al. Thousands of microbial genomes shed light on interconnected biogeochemical processes in an aquifer system. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13219.

- Dodd, R.J.; Sharpley, A.N. Recognizing the role of soil organic phosphorus in soil fertility and water quality. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2015, 105, 282–293.

- Tao, G.-C.; Tian, S.-J.; Cai, M.-Y.; Xie, G.-H. Phosphate-Solubilizing and -Mineralizing Abilities of Bacteria Isolated from Soils. Pedosphere 2008, 18, 515–523.

- Müller, C.; Bünemann, E.K. A 33P tracing model for quantifying gross P transformation rates in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 76, 218–226.

- Bi, Q.F.; Li, K.J.; Zheng, B.X.; Liu, X.P.; Li, H.Z.; Jin, B.J.; Ding, K.; Yang, X.R.; Lin, X.Y.; Zhu, Y.G. Partial replacement of inorganic phosphorus (P) by organic manure reshapes phosphate mobilizing bacterial community and promotes P bioavailability in a paddy soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703.

- Sun, F.; Song, C.; Wang, M.; Lai, D.Y.F.; Tariq, A.; Zeng, F.; Zhong, Q.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Peng, C. Long-term increase in rainfall decreases soil organic phosphorus decomposition in tropical forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020.

- Bai, J.H.; Yu, L.; Ye, X.F.; Yu, Z.B.; Guan, Y.N.; Li, X.W.; Cui, B.S.; Liu, X.H. Organic phosphorus mineralization characteristics in sediments from the coastal salt marshes of a Chinese delta under simulated tidal cycles. J. Soils Sediment. 2020, 20, 513–523.

- Bi, Q.-F.; Zheng, B.-X.; Lin, X.-Y.; Li, K.-J.; Liu, X.-P.; Hao, X.-L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.-B.; Jaisi, D.P.; Zhu, Y.-G. The microbial cycling of phosphorus on long-term fertilized soil: Insights from phosphate oxygen isotope ratios. Chem. Geol. 2018, 483, 56–64.

- Nannipieri, P.; Giagnoni, L.; Landi, L.; Renella, G. Role of Phosphatase Enzymes in Soil. In Phosphorus in Action; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 215–243.

- Zheng, L.; Ren, M.L.; Xie, E.; Ding, A.Z.; Liu, Y.; Deng, S.Q.; Zhang, D.Y. Roles of Phosphorus Sources in Microbial Community Assembly for the Removal of Organic Matters and Ammonia in Activated Sludge. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1023.

- Rodriguez, H.; Fraga, R.; Gonzalez, T.; Bashan, Y. Genetics of phosphate solubilization and its potential applications for improving plant growth-promoting bacteria. Plant Soil 2006, 287, 15–21.

- Alori, E.T.; Glick, B.R.; Babalola, O.O. Microbial Phosphorus Solubilization and Its Potential for Use in Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 971.

- Passariello, C.; Schippa, S.; Iori, P.; Berlutti, F.; Thaller, M.C.; Rossolini, G.M. The molecular class C acid phosphatase of Chryseobacterium meningosepticum (OlpA) is a broad-spectrum nucleotidase with preferential activity on 5′-nucleotides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2003, 1648, 203–209.

- Jiang, L.H.; Liu, X.D.; Yin, H.Q.; Liang, Y.L.; Liu, H.W.; Miao, B.; Peng, Q.Q.; Meng, D.L.; Wang, S.Q.; Yang, J.J.; et al. The utilization of biomineralization technique based on microbial induced phosphate precipitation in remediation of potentially toxic ions contaminated soil: A mini review. Ecotox. Environ. Safety 2020, 191, 110009.

- Xie, E.; Su, Y.P.; Deng, S.Q.; Kontopyrgou, M.; Zhang, D.Y. Significant influence of phosphorus resources on the growth and alkaline phosphatase activities of Microcystis aeruginosa. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115807.

- Xie, E.; Li, F.F.; Wang, C.Z.; Shi, W.; Huang, C.; Fa, K.Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, D.Y. Roles of sulfur compounds in growth and alkaline phosphatase activities of Microcystis aeruginosa under phosphorus deficiency stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2020, 27, 21533–21541.

- Rodriguez, H.; Fraga, R. Phosphate solubilizing bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion. Biotechnol. Adv. 1999, 17, 319–339.

- Liang, X.; Csetenyi, L.; Gadd, G.M. Lead Bioprecipitation by Yeasts Utilizing Organic Phosphorus Substrates. Geomicrobiol. J. 2016, 33, 294–307.

- Farias, N.; Almeida, I.; Meneses, C. New Bacterial Phytase through Metagenomic Prospection. Molecules 2018, 23, 448.

- Kour, D.; Rana, K.L.; Kaur, T.; Yadav, N.; Yadav, A.N.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, V.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Saxena, A.K. Biodiversity, current developments and potential biotechnological applications of phosphorus-solubilizing and -mobilizing microbes: A review. Pedosphere 2021, 31, 43–75.

- Cong, W.F.; Suriyagoda, L.D.B.; Lambers, H. Tightening the Phosphorus Cycle through Phosphorus-Efficient Crop Genotypes. Trends Plant Sci. 2020.

- Fixen, P.E.; Johnston, A.M. World fertilizer nutrient reserves: A view to the future. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 1001–1005.

- Turan, M.; Ataoğlu, N.; Şahιn, F. Evaluation of the Capacity of Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria and Fungi on Different Forms of Phosphorus in Liquid Culture. J. Sustain. Agr. 2006, 28, 99–108.

- Kucey, R.M. Increased Phosphorus Uptake by Wheat and Field Beans Inoculated with a Phosphorus-Solubilizing Penicillium bilaji Strain and with Vesicular-Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 2699–2703.

- Liu, S.T.; Lee, L.Y.; Tai, C.Y.; Hung, C.H.; Chang, Y.S.; Wolfram, J.H.; Rogers, R.; Goldstein, A.H. Cloning of an Erwinia herbicola gene necessary for gluconic acid production and enhanced mineral phosphate solubilization in Escherichia coli HB101: Nucleotide sequence and probable involvement in biosynthesis of the coenzyme pyrroloquinoline quinone. J. Bacteriol. 1992, 174, 5814–5819.

- Wang, Q.; Xiao, C.Q.; Feng, B.; Chi, R. Phosphate rock solubilization and the potential for lead immobilization by a phosphate-solubilizing bacterium (Pseudomonas sp.). J. Environ. Sci. Heal. A 2020, 55, 411–420.

- Alaylar, B.; Egamberdieva, D.; Gulluce, M.; Karadayi, M.; Arora, N.K. Integration of molecular tools in microbial phosphate solubilization research in agriculture perspective. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 93.

- Halder, A.K.; Chakrabartty, P.K. Solubilization of inorganic phosphate byRhizobium. Folia Microbiol. 1993, 38, 325–330.

- Sperber, J.I. Solution of mineral phosphate by soil bacteria. Nature 1957, 180, 994–995.

- Zaidi, A.; Ahemad, M.; Oves, M.; Ahmad, E.; Khan, M.S. Role of Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria in Legume Improvement. In Microbes for Legume Improvement; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 273–292.

- Jiang, Y.F.; Tian, J.; Ge, F. New Insight into Carboxylic Acid Metabolisms and pH Regulations During Insoluble Phosphate Solubilisation Process by Penicillium oxalicum PSF-4. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 4095–4103.

- Mackay, J.E.; Cavagnaro, T.R.; Müller Stöver, D.S.; Macdonald, L.M.; Grønlund, M.; Jakobsen, I. A key role for arbuscular mycorrhiza in plant acquisition of P from sewage sludge recycled to soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 115, 11–20.

- Zai, X.M.; Zhang, H.S.; Hao, Z.P. Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Phosphate-Solubilizing Fungus on the Rooting, Growth and Rhizosphere Niche of Beach Plum (Prunus maritima) Cuttings in a Phosphorus-deficient Soil. J. Am. Pomol. Soc. 2017, 71, 226–235.

- Jog, R.; Pandya, M.; Nareshkumar, G.; Rajkumar, S. Mechanism of phosphate solubilization and antifungal activity of Streptomyces spp. isolated from wheat roots and rhizosphere and their application in improving plant growth. Microbiology 2014, 160, 778–788.

- Hamdali, H.; Smirnov, A.; Esnault, C.; Ouhdouch, Y.; Virolle, M.J. Physiological studies and comparative analysis of rock phosphate solubilization abilities of Actinomycetales originating from Moroccan phosphate mines and of Streptomyces lividans. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2010, 44, 24–31.

- Hamdali, H.; Bouizgarne, B.; Hafidi, M.; Lebrihi, A.; Virolle, M.J.; Ouhdouch, Y. Screening for rock phosphate solubilizing Actinomycetes from Moroccan phosphate mines. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2008, 38, 12–19.

- Chaiharn, M.; Pathom-aree, W.; Sujada, N.; Lumyong, S. Characterization of Phosphate Solubilizing Streptomyces as a Biofertilizer. Chiang Mai. J. Sci. 2018, 45, 701–716.

- Farhat, M.B.; Boukhris, I.; Chouayekh, H. Mineral phosphate solubilization by Streptomyces sp. CTM396 involves the excretion of gluconic acid and is stimulated by humic acids. Fems Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362.

- Yandigeri, M.S.; Yadav, A.K.; Srinivasan, R.; Kashyap, S.; Pabbi, S. Studies on mineral phosphate solubilization by cyanobacteria Westiellopsis and Anabaena. Microbiology 2011, 80, 558–565.

- Baumann, K.; Jung, P.; Samolov, E.; Lehnert, L.W.; Budel, B.; Karsten, U.; Bendix, J.; Achilles, S.; Schermer, M.; Matus, F.; et al. Biological soil crusts along a climatic gradient in Chile: Richness and imprints of phototrophic microorganisms in phosphorus biogeochemical cycling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 127, 286–300.

- Nahas, E. Factors determining rock phosphate solubilization by microorganisms isolated from soil. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1996, 12, 567–572.

- Luyckx, L.; Geerts, S.; Van Caneghem, J. Closing the phosphorus cycle: Multi-criteria techno-economic optimization of phosphorus extraction from wastewater treatment sludge ash. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 135543.

- Illmer, P.; Schinner, F. Solubilization of inorganic calcium phosphates-solubilization mechanisms. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1995, 27, 257–263.

- Yi, Y.; Huang, W.; Ge, Y. Exopolysaccharide: A novel important factor in the microbial dissolution of tricalcium phosphate. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 24, 1059–1065.

- Whitton, B.A.; Grainger, S.L.J.; Hawley, G.R.W.; Simon, J.W. Cell-bound and extracellular phosphatase activities of cyanobacterial isolates. Microb. Ecol. 1991, 21, 85–98.

- Zhao, X.; Lin, Q.; Li, B. The solubilization of four insoluble phosphates by some microorganisms. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 2002, 42, 236–241.

- Osorno, L.; Osorio, N.W.; Habte, M. Phosphate desorption by a soil fungus in selected Hawaiian soils differing in their mineralogy. Trop. Agric. 2018, 95, 154–166.

- Osorio, N.W.; Habte, M. Phosphate desorption from the surface of soil mineral particles by a phosphate-solubilizing fungus. Biol. Fert. Soils 2012, 49, 481–486.

- He, Z.; Zhu, J. Microbial utilization and transformation of phosphate adsorbed by variable charge minerals. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1998, 30, 917–923.

- Eriksson, A.K.; Gustafsson, J.P.; Hesterberg, D. Phosphorus speciation of clay fractions from long-term fertility experiments in Sweden. Geoderma 2015, 241-242, 68–74.

- Wu, S.J.; Zhao, Y.P.; Chen, Y.Y.; Dong, X.M.; Wang, M.Y.; Wang, G.X. Sulfur cycling in freshwater sediments: A cryptic driving force of iron deposition and phosphorus mobilization. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1294–1303.

- de Campos, M.; Antonangelo, J.A.; Alleoni, L.R.F. Phosphorus sorption index in humid tropical soils. Soil Till. Res. 2016, 156, 110–118.

- Qiao, Z.; Hong, J.; Li, L.; Liu, C. Effect of Phosphobacterias on Nutrient, Enzyme Activities and Phosphorus Adsorption—Desorption Characteristics in a Reclaimed Soil. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2017, 31, 166–171.

- Osorio, N.W.; Habte, M. Soil Phosphate Desorption Induced by a Phosphate-Solubilizing Fungus. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant 2014, 45, 451–460.

- Hoberg, E.; Marschner, P.; Lieberei, R. Organic acid exudation and pH changes by Gordonia sp. and Pseudomonas fluorescens grown with P adsorbed to goethite. Microbiol. Res. 2005, 160, 177–187.

- Andrade, F.V.; Mendonça, E.S.; Silva, I.R. Organic Acids and Diffusive Flux of Organic and Inorganic Phosphorus in Sandy-Loam and Clayey Latosols. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant 2013, 44, 1211–1223.

- Oburger, E.; Leitner, D.; Jones, D.L.; Zygalakis, K.C.; Schnepf, A.; Roose, T. Adsorption and desorption dynamics of citric acid anions in soil. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2011, 62, 733–742.

- Suriyagoda, L.B.D.; Tibbett, M.; Edmonds-Tibbett, T.; Cawthray, G.R.; Ryan, M.H. Poor regulation of phosphorus uptake and rhizosphere carboxylates in three phosphorus-hyperaccumulating species of Ptilotus. Plant Soil 2015, 402, 145–158.

- Pastore, G.; Kaiser, K.; Kernchen, S.; Spohn, M. Microbial release of apatite- and goethite-bound phosphate in acidic forest soils. Geoderma 2020, 370, 114360.

- Li, C.K.; Li, Q.S.; Wang, Z.P.; Ji, G.N.; Zhao, H.; Gao, F.; Su, M.; Jiao, J.G.; Li, Z.; Li, H.X. Environmental fungi and bacteria facilitate lecithin decomposition and the transformation of phosphorus to apatite. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15291.

- Huang, D.; Deng, R.; Wan, J.; Zeng, G.; Xue, W.; Wen, X.; Zhou, C.; Hu, L.; Liu, X.; Xu, P.; et al. Remediation of lead-contaminated sediment by biochar-supported nano-chlorapatite: Accompanied with the change of available phosphorus and organic matters. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 348, 109–116.

- Lei, Y.; Remmers, J.C.; Saakes, M.; van der Weijden, R.D.; Buisman, C.J.N. Is There a Precipitation Sequence in Municipal Wastewater Induced by Electrolysis? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 8399–8407.

- DeJong, J.T.; Mortensen, B.M.; Martinez, B.C.; Nelson, D.C. Bio-mediated soil improvement. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 197–210.

- Eighmy, T.T.; Kinner, A.E.; Shaw, E.L.; Eusden, J.D.; Francis, C.A. Chlorapatite (Ca5(PO4)3Cl) Characterization by XPS: An Environmentally Important Secondary Mineral. Surf. Sci. Spectra 1999, 6, 210–218.

- Mutschke, A.; Wylezich, T.; Ritter, C.; Karttunen, A.J.; Kunkel, N. An Unprecedented Fully H-Substituted Phosphate Hydride Sr5(PO4)3H Expanding the Apatite Family. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 2019, 5073–5076.

- Hirschler, A.; Lucas, J.; Hubert, J.C. Apatite genesis: A biologically induced or biologically controlled mineral formation process? Geomicrobiol. J. 1990, 8, 47–56.

- Chang, S.J.; Blake, R.E.; Stout, L.M.; Kim, S.J. Oxygen isotope, micro-textural and molecular evidence for the role of microorganisms in formation of hydroxylapatite in limestone caves, South Korea. Chem. Geol. 2010, 276, 209–224.

- Deng, S.; Zhang, C.; Dang, Y.; Collins, R.N.; Kinsela, A.S.; Tian, J.; Holmes, D.E.; Li, H.; Qiu, B.; Cheng, X.; et al. Iron Transformation and Its Role in Phosphorus Immobilization in a UCT-MBR with Vivianite Formation Enhancement. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 12539–12549.

- Fontaine, L.; Thiffault, N.; Paré, D.; Fortin, J.A.; Piché, Y. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria isolated from ectomycorrhizal mycelium of Picea glaucaare highly efficient at fluorapatite weathering. Botany 2016, 94, 1183–1193.

- Reyes, I.; Bernier, L.; Simard, R.R.; Tanguay, P.; Antoun, H. Characteristics of phosphate solubilization by an isolate of a tropical Penicillium rugulosum and two UV-induced mutants. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1999, 28, 291–295.

- Iuliano, M.; Ciavatta, L.; De Tommaso, G. On the Solubility Constant of Strengite. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2007, 71, 1137–1140.

- Ae, N.; Otani, T.; Makino, T.; Tazawa, J. Role of cell wall of groundnut roots in solubilizing sparingly soluble phosphorus in soil. Plant Soil 1996, 186, 197–204.

- Kranzler, C.; Kessler, N.; Keren, N.; Shaked, Y. Enhanced ferrihydrite dissolution by a unicellular, planktonic Cyanobacterium: A biological contribution to particulate iron bioavailability. Environ. Microbiol 2016, 18, 5101–5111.

- Chen, Z.; Pan, X.; Chen, H.; Guan, X.; Lin, Z. Biomineralization of Pb(II) into Pb-hydroxyapatite induced by Bacillus cereus 12-2 isolated from Lead-Zinc mine tailings. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 301, 531–537.

- Zhang, K.J.; Xue, Y.W.; Zhang, J.Q.; Hu, X.L. Removal of lead from acidic wastewater by bio-mineralized bacteria with pH self-regulation. Chemosphere 2020, 241, 125041.

- Wang, T.J.; Wang, S.L.; Tang, X.C.; Fan, X.P.; Yang, S.; Yao, L.G.; Li, Y.D.; Han, H. Isolation of urease-producing bacteria and their effects on reducing Cd and Pb accumulation in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2020, 27, 8707–8718.

- Park, J.H.; Bolan, N.; Megharaj, M.; Naidu, R.; Chung, J.W. Bacterial-Assisted Immobilization of Lead in Soils: Implications for Remediation. Pedologist 2011, 54, 162–174.

- White, D.A.; Hafsteinsdottir, E.G.; Gore, D.B.; Thorogood, G.; Stark, S.C. Formation and stability of Pb-, Zn- and Cu-PO(4) phases at low temperatures: Implications for heavy metal fixation in polar environments. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 161, 143–153.

- Naik, M.M.; Dubey, S.K. Lead resistant bacteria: Lead resistance mechanisms, their applications in lead bioremediation and biomonitoring. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 98, 1–7.

- Zhao, W.-W.; Zhu, G.; Daugulis, A.J.; Chen, Q.; Ma, H.-Y.; Zheng, P.; Liang, J.; Ma, X.-k. Removal and biomineralization of Pb2+ in water by fungus Phanerochaete chrysoporium. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260.

- Xu, Y.; Schwartz, F.W. Lead immobilization by hydroxyapatite in aqueous solutions. J. Contam. Hydrol. 1994, 15, 187–206.

- Xu, J.C.; Huang, L.M.; Chen, C.Y.; Wang, J.; Long, X.X. Effective lead immobilization by phosphate rock solubilization mediated by phosphate rock amendment and phosphate solubilizing bacteria. Chemosphere 2019, 237, 124540.

- Schütze, E.; Weist, A.; Klose, M.; Wach, T.; Schumann, M.; Nietzsche, S.; Merten, D.; Baumert, J.; Majzlan, J.; Kothe, E. Taking nature into lab: Biomineralization by heavy metal-resistant Streptomycetes in soil. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 3605–3614.

- Jiang, K.; Qi, H.-W.; Hu, R.-Z. Element mobilization and redistribution under extreme tropical weathering of basalts from the Hainan Island, South China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2018, 158, 80–102.

- Ouahmane, L.; Revel, J.C.; Hafidi, M.; Thioulouse, J.; Prin, Y.; Galiana, A.; Dreyfus, B.; Duponnois, R. Responses of Pinus halepensis growth, soil microbial catabolic functions and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria after rock phosphate amendment and ectomycorrhizal inoculation. Plant Soil 2009, 320, 169–179.

- Buss, H.L.; Mathur, R.; White, A.F.; Brantley, S.L. Phosphorus and iron cycling in deep saprolite, Luquillo Mountains, Puerto Rico. Chem. Geol. 2010, 269, 52–61.

- Garland, G.; Bunemann, E.K.; Oberson, A.; Frossard, E.; Snapp, S.; Chikowo, R.; Six, J. Phosphorus cycling within soil aggregate fractions of a highly weathered tropical soil: A conceptual model. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 116, 91–98.

- Rathi, M.; Gaur, N. Phosphate solubilizing bacteria as biofertilizer and its applications. J. Pharm. Res. 2016, 10, 146–148.

- Berhe, A.A.; Barnes, R.T.; Six, J.; Marin-Spiotta, E. Role of Soil Erosion in Biogeochemical Cycling of Essential Elements: Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2018, 46, 521–548.

- Zhou, J.; Wang, H.; Cravotta, C.A.; Dong, Q.; Xiang, X. Dissolution of Fluorapatite by Pseudomonas fluorescens P35 Resulting in Fluorine Release. Geomicrobiol. J. 2016, 1–13.

- Bashan, Y.; Kamnev, A.A.; de-Bashan, L.E. Tricalcium phosphate is inappropriate as a universal selection factor for isolating and testing phosphate-solubilizing bacteria that enhance plant growth: A proposal for an alternative procedure. Biol. Fert. Soils 2012, 49, 465–479.

- Qiu, S.; Lian, B. Weathering of phosphorus-bearing mineral powder and calcium phosphate by Aspergillus niger. Chinese J. Geochem. 2012, 31, 390–397.

- Hanane, H. Isolation and characterization of rock phosphate solubilizing actinobacteria from a Togolese phosphate mine. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 11.

- Puente, M.E.; Bashan, Y.; Li, C.Y.; Lebsky, V.K. Microbial populations and activities in the rhizoplane of rock-weathering desert plants. I. Root colonization and weathering of igneous rocks. Plant Biol. 2004, 6, 629–642.

- Mendes, G.d.O.; Galvez, A.; Vassileva, M.; Vassilev, N. Fermentation liquid containing microbially solubilized P significantly improved plant growth and P uptake in both soil and soilless experiments. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2017, 117, 208–211.

- Ahemad, M. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-assisted phytoremediation of metalliferous soils: A review. 3 Biotech 2015, 5, 111–121.

- Estrada-Bonilla, G.A.; Durrer, A.; Cardoso, E.J.B.N. Use of compost and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria affect sugarcane mineral nutrition, phosphorus availability, and the soil bacterial community. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 157, 103760.

- Raymond, N.S.; Gomez-Munoz, B.; van der Bom, F.J.T.; Nybroe, O.; Jensen, L.S.; Muller-Stover, D.S.; Oberson, A.; Richardson, A.E. Phosphate-solubilising microorganisms for improved crop productivity: A critical assessment. New Phytol. 2020.

- Meyer, G.; Maurhofer, M.; Frossard, E.; Gamper, H.A.; Mäder, P.; Mészáros, É.; Schönholzer-Mauclaire, L.; Symanczik, S.; Oberson, A. Pseudomonas protegens CHA0 does not increase phosphorus uptake from 33P labeled synthetic hydroxyapatite by wheat grown on calcareous soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 131, 217–228.

- Romero-Perdomo, F.; Beltrán, I.; Mendoza-Labrador, J.; Estrada-Bonilla, G.; Bonilla, R. Phosphorus Nutrition and Growth of Cotton Plants Inoculated With Growth-Promoting Bacteria Under Low Phosphate Availability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4.

- Khan, M.S.; Zaidi, A.; Wani, P.A.; Oves, M. Role of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria in the Remediation of Metal Contaminated Soils: A Review. In Organic Farming, Pest Control and Remediation of Soil Pollutants: Organic Farming, Pest Control and Remediation of Soil Pollutants; Lichtfouse, E., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 319–350.

- Yahaghi, Z.; Shirvani, M.; Nourbakhsh, F.; de la Pena, T.C.; Pueyo, J.J.; Talebi, M. Isolation and Characterization of Pb-Solubilizing Bacteria and Their Effects on Pb Uptake by Brassica juncea: Implications for Microbe-Assisted Phytoremediation. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 28, 1156–1167.

- Zheng, B.X.; Ding, K.; Yang, X.R.; Wadaan, M.A.M.; Hozzein, W.N.; Penuelas, J.; Zhu, Y.G. Straw biochar increases the abundance of inorganic phosphate solubilizing bacterial community for better rape (Brassica napus) growth and phosphate uptake. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 1113–1120.

- Kumar, A.; Teja, E.S.; Mathur, V.; Kumari, R. Phosphate-Solubilizing Fungi: Current Perspective, Mechanisms and Potential Agricultural Applications. In Agriculturally Important Fungi for Sustainable Agriculture: Volume 1: Perspective for Diversity and Crop Productivity; Yadav, A.N., Mishra, S., Kour, D., Yadav, N., Kumar, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 121–141.

- Smith, S.E.; Jakobsen, I.; Gronlund, M.; Smith, F.A. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizas in plant phosphorus nutrition: Interactions between pathways of phosphorus uptake in arbuscular mycorrhizal roots have important implications for understanding and manipulating plant phosphorus acquisition. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1050–1057.

- Arora, N.K.; Tewari, S.; Singh, R. Multifaceted Plant-Associated Microbes and Their Mechanisms Diminish the Concept of Direct and Indirect PGPRs; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2013; pp. 411–449.

- Tisserant, E.; Malbreil, M.; Kuo, A.; Kohler, A.; Symeonidi, A.; Balestrini, R.; Charron, P.; Duensing, N.; Frei dit Frey, N.; Gianinazzi-Pearson, V.; et al. Genome of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus provides insight into the oldest plant symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20117–20122.

- Zhang, L.; Xu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Hodge, A.; Feng, G. Carbon and phosphorus exchange may enable cooperation between an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and a phosphate-solubilizing bacterium. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1022–1032.

- Jiang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; George, T.S.; Feng, G. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance mineralisation of organic phosphorus by carrying bacteria along their extraradical hyphae. New Phytol. 2020.

- Zhang, L.; Feng, G.; Declerck, S. Signal beyond nutrient, fructose, exuded by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus triggers phytate mineralization by a phosphate solubilizing bacterium. ISME J. 2018, 12, 2339–2351.

- Liu, N.; Shao, C.; Sun, H.; Liu, Z.B.; Guan, Y.M.; Wu, L.J.; Zhang, L.L.; Pan, X.X.; Zhang, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.Y.; et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi biofertilizer improves American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) growth under the continuous cropping regime. Geoderma 2020, 363, 114155.

- Hao, X.L.; Zhu, Y.G.; Nybroe, O.; Nicolaisen, M.H. The Composition and Phosphorus Cycling Potential of Bacterial Communities Associated With Hyphae of Penicillium in Soil Are Strongly Affected by Soil Origin. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 2951.

- Hong, J.K.; Kim, S.B.; Lyou, E.S.; Lee, T.K. Microbial phenomics linking the phenotype to function: The potential of Raman spectroscopy. J. Microbiol. 2021.

- Li, H.Z.; Bi, Q.F.; Yang, K.; Zheng, B.X.; Pu, Q.; Cui, L. D2O-Isotope-Labeling Approach to Probing Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria in Complex Soil Communities by Single-Cell Raman Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 2239–2246.