沸石是一种具有优异的水热稳定性的结晶微孔材料,是最重要的工业无机固体之一,已广泛应用于离子交换,吸附,分离,医学,光电和催化领域。

The traditional hydrothermal method to prepare zeolite will inevitably use a large amount of water as a solvent, which will lead to higher autogenous pressure, low efficiency, and wastewater pollution. The solvent-free method can be used to synthesize various types of zeolites by mechanical mixing, grinding, and heating of solid raw materials, which exhibits the apparent advantages of high yield, low pollution, and high efficiency. This review mainly introduces the development process of solvent-free synthesis, preparation of hierarchical zeolite, morphology control, synthesis mechanism and applications of solvent-free methods. It can be believed that solvent-free methods will become a research focus and have enormous industrial application potential.

- zeolites

- solvent-free method

- mechanism

- applications

1.简介

1. Introduction

Zeolites, a kind of crystalline microporous material with outstanding hydrothermal stability, are one of the most important industrial inorganic solids [1][2][3][4], which have been widely applied in the field of ion exchange, adsorption, separation, medicine, optoelectronics and catalysis [5][6][7][8][9][10][11]. Zeolites can be obtained from natural ores or artificially synthesized. Generally, artificially synthesized zeolites have higher crystallinity and are widely used for ion exchangers and catalysts [12]. Hydrothermal synthesis has become a conventional method for zeolite preparation since Barrer and Milton proposed hydrothermal synthesis technology by simulating the natural conditions [13].

However, the hydrothermal method inevitably uses a lot of water as a solvent. Though water can be considered harmless, the excessive addition of water can cause many problems including the following: (1) filling too high with water will produce higher autogenous pressure, which will lead to equipment safety problems; (2) the space utilization efficiency of the autoclave is low, and the product yield is low; (3) the pollution from wastewater [14]. Therefore, synthesizing zeolites under anhydrous conditions reducing or removing solvents from the synthesis process is of great significance and conforms to the concept of green chemistry [15][16].

Pioneering research has challenged the necessity of water during zeolite synthesis. In 1990, Xu et al. [17] developed a new vapor-phase transport (VPT) method for the synthesis of zeolites, successfully avoiding the use of large amounts of water solvents during the crystallization process. In 1994, Althoff et al. [18] used ammonium fluoride instead of water vapor and proved that the presence of water during the crystallization process is not necessary.

Although the VPT method can solve some of the problems, it still necessary to use a lot of solvents in the process of preparing xerogels. In 2012, Xiao et al. [19] reported a solvent-free method of preparing zeolites without solvents by mechanical grinding and heating raw materials without adding additional water. In the solvent-free process, there is no evident free water or the use of other solvents instead of water. It does not really mean that there is no water in the system. This review mainly introduces the development process of solvent-free synthesis, preparation of hierarchical zeolite, morphology control, synthesis mechanism and applications of solvent-free methods.

2. Vapor-Phase Transport Technology

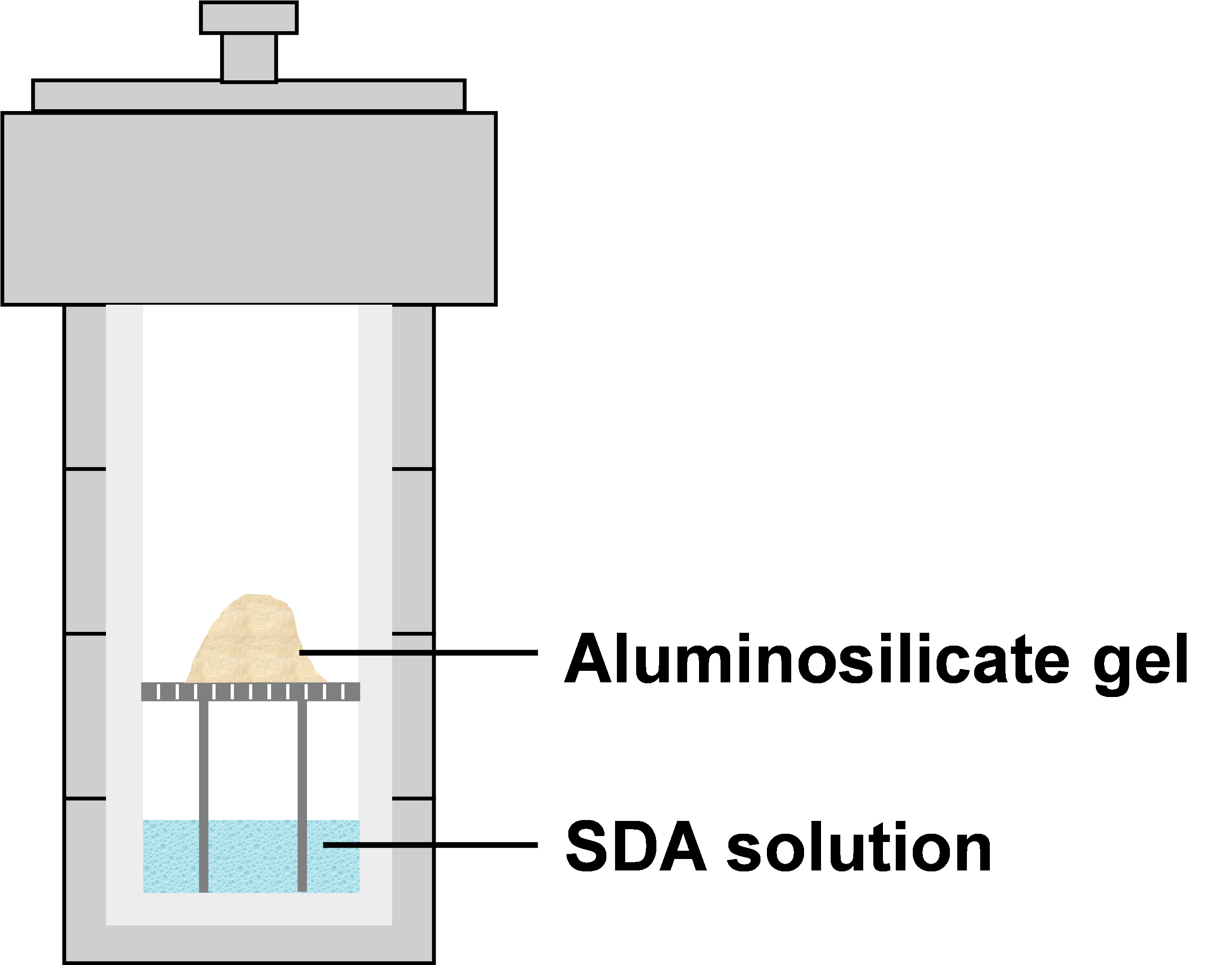

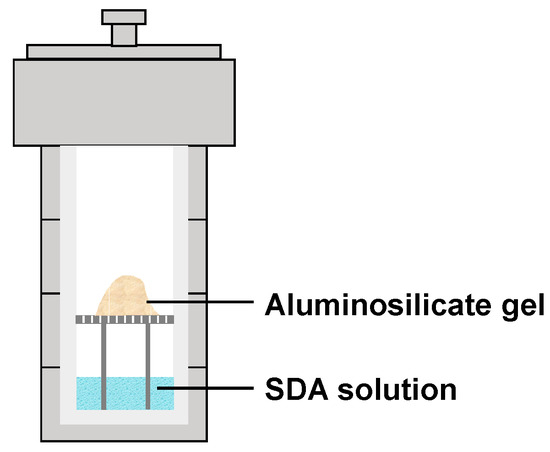

In response to a series of problems caused by the excessive usage of water in the synthesis of zeolite, dry-gel conversion (DGC) and vapor-phase transport (VPT) techniques were developed [20]. The dry-gel sample was placed above the structure-directing agent (SDA) solution and reacted with water and amine vapors at a sealed autoclave under elevated temperature and autogenous pressure (Figure 1) [17][21]. ZSM-5 was successfully synthesized at 180–200 ◦C for 5–7 days. The mixed solution of water and amine was separated from the solid phase, which facilitated the recovery of the solution and could be reused to avoid wastewater treatment. Moreover, the cost of organic amines occupied a large part of the synthesis of zeolite, which reduced the consequent cost of the product.

Figure 1. Synthesis of zeolites by vapor-phase transport (VPT) method.

To explore the necessity of water in the VPT method, Althoff et al. [18] treated the precursor at 650 ◦C for 24 h to form a dry powder. In the subsequent crystallization process, they used ammonium fluoride instead of directly using water vapor and gradually reduced the water content in the system ending in an absolutely dry mixture. They found that zeolite was still synthesized successfully in the case of extremely anhydrous conditions, indicating that water was not necessary for the crystallization process. They suggested that SiF4 was a mobile phase formed by the transformation of the amorphous precursor.

Kim et al. [22] and Matsukata et al. [23] improved relevant studies and proved that the gas phase transport technology could be applied to the synthesis of various zeolites, for example, MFI, FER, MOR and so on. Besides, the VPT method can expand the compositions of zeolite formation.

3. Solvent-Free Synthesis of Zeolite

The VPT technique addressed the problem of excessive usage of water in the crystallization process of zeolite. Through the success of VPT, it can be proposed that a solvent was not necessary for the crystallization process of zeolite. However, it is worth noting that an abundance of water was essential for the preparation of the gel. To address these problems, Xiao et al. [19] developed a solvent-free method based on mechanochemistry. Several of the most industrially important zeolites, with MFI, MOR, FAU, SOD, and *BEA frameworks, were successfully synthesized with this approach. The specific surface area, pore volume and pore size of the solvent-free ZSM-5 were 276 m2·g−1, 0.13 cm3·g−1 and 0.53 nm, respectively. Interestingly, zeolite seeds could replace SDA to direct the synthesis of Beta zeolite under solvent-free conditions, which could greatly reduce the use of SDA. Removing the use of expensive and toxic organic templates and excessive solvents can reduce the costs of zeolite synthesis and environmental pollution caused by calcined template agents and wastewater discharge, which would be the ultimate goal of synthesizing zeolite in an environmentally friendly and economical way.

Xiao et al. [24] conducted extended research on solvent-free synthesis combined with the template-free method with the assistance of NH4F. Eventually, silicalite-1, Beta, EU-1, and ZSM-22 zeolites were successfully synthesized. However, zeolite seeds were still necessary by this method. Thus, how to avoid using zeolite seeds should be the next research focus.

Gao et al. [25] successfully synthesized a high-crystallinity MOR zeolite in laboratory-scale conditions (650 g MOR was produced by 1 L autoclave) through the solvent-free method without an organic template. The specific surface area and pore volume of MOR zeolites synthesized at 473 K for 48 h were 392.1 m2·g−1 and 0.314 cm3·g−1, respectively, which are similar to those synthesized by conventional methods (397.9 m2·g−1 and 0.093 cm3·g−1). Though the pore volume was much larger than conventional MOR zeolites, the relative crystallinity was only 70%, which required further improvement. Notably, MFI structure appeared when SBA-15 was used as silica source, which indicated that it was possible to synthesize the MFI structure through a solvent-free and template-free method. Nada et al. [26][27] conducted related studies; they found that different zeolites can be synthesized by changing the ratio of raw materials. The higher Si content and lower Na content in the mixture were beneficial to ZSM-5 zeolites, while higher Na and Al contents were beneficial to mordenite, which was similar to the observations of synthesis. Currently, only a few zeolites can be synthesized without the use of templates and zeolite seeds by the solvent-free method.

In addition to the synthesis of aluminosilicates, the solvent-free method was extended to the preparation of aluminophosphates. Jin et al. [28] reported the use of the solvent-free method in the synthesis of silicoaluminophosphate, aluminophosphate, and heteroatom containing aluminophosphate zeolites. The specific surface area and pore volume of the solvent-free SAPO-34 were 459 m2·g−1 and 0.27 cm3·g−1, respectively. The solvent-free SAPO-34 had a conversion of close to 100%. The total yield was 88.9%, which was close to that of the SAPO-34 prepared by the traditional method (91.3%). Moreover, the obtained SAPO-34 exhibited the hierarchically porous structure which was beneficial for improving the selectivity of propylene and butylene and reducing ethylene selectivity.

It is worth noting that heteroatom can be conveniently incorporated into the framework of zeolites by solvent-free method, which has been commonly used in industry [29][30][31][32][33]. Generally, metal-exchanged zeolites were synthesized by performing multiple ion ex- changes under hydrothermal conditions, which was complicated and also produced a lot of wastewater. Using the solvent-free method to synthesize heteroatom zeolites could overcome those shortcomings. Ma et al. [34] synthesized heteroatom zeolites in one pot through the solvent-free method by mechanical mixing, grinding and heating raw materials (aluminosilicate gel, templates, and metal-amine complexes). The 27Al MAS NMR spectrum of Cu-SSZ-13 has shown that there were no extra-framework aluminum species in the sample, which was in good agreement with the conventional hydrothermal method. Moreover, the yield of Cu-SSZ-13 was 98.1%, which was much higher than traditional ion exchange (55.6%) [35].

The solvent-free method could also be applied to metal-doped silicoaluminophosphate zeolites. Wang et al. [36] synthesized nanoscale Mg incorporated SAPO-34 by the solvent-free method. In this process, layered clay mineral, a cheap Mg-rich aluminosilicate, was used as Mg, Si and Al source. Besides, it also acted as a hard template to significantly reduce crystal size. The product had an Mg content of up to 6.65% and a small crystal size (50 nm), which was conducive to mass transfer. Zeolites with an Mg content of 3% exhibited a chloromethane conversion of almost 100% and a high light olefin selectivity of 88.1%.

4. Formation of Hierarchical Pore Structure

Zeolites have received extensive attention due to their easily adjustable physicochemical properties. However, the diffusion limitation of micropores will constrain the mass transfer of the reactants and products, thereby reducing the kinetics of the reaction. Therefore, the hierarchically porous structure is necessary for macromolecular reactions. Commonly, the synthesis method of hierarchically porous zeolites is classified into bottom-up and top-down methods [37][38][39]. In the hydrothermal synthesis process, different methods that utilize hard-template or soft-template are categorized as bottom-up approaches, while those by treating zeolites by dealumination and desilication are classified as top-down methods [39]. Herein, the concept is still used in the solvent-free method.

4.1. Bottom-Up Strategy

Jin et al. [40] synthesized hierarchically porous aluminophosphate-based zeolites through the solvent-free method. In the synthesis of zeolites with AEL structure (APO-11), di-n-propylamine phosphate (DPA·H3PO4) and boehmite were ground at room temperature and heated at 200 °C. After calcination at 600 °C for 4 h, the relative pressure of the sample increased sharply at 10−6–0.01, which could be attributed to the filling of micropores. Meanwhile, a hysteresis loop can be observed at a relative pressure of 0.45–0.95, suggesting the presence of mesoporosity and macroporosity in the sample. DPA·H3PO4 was served as an organic template and phosphorus source, and avoided the volatilization of amines during synthesis. Sheng et al. [41] found that a large amount of gaseous di-n-propylamine (DPA) molecules could be quickly released from DPA·H3PO4 during the crystallization process, which could be served as “porogens” for the formation of mesoporosity.

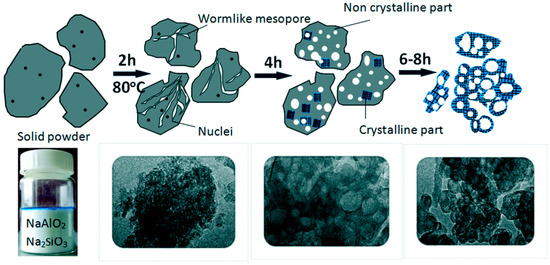

Zeng et al. [42] synthesized hierarchically porous SOD zeolites by the solvent-free method with organosilane as a mesopore-generating agent. Figure 2 illuminated the schematic process of the growth mechanism for hierarchically porous SOD via the solvent-free method. Before crystallization after grinding, the samples formed an amorphous solid. After crystallization for 2 h, worm-like mesoporous channels resulting from amorphous aggregates could be observed. After crystallization for 4 h, voids or cavities were detected, which would result in the formation of cell-like SOD zeolite. The synthesized SOD zeolites exhibited small mesopores (4.6 nm) owing to organosilane surfactant and meso-macropores (20–55 nm) attributed to interparticle voids.

![Figure 2. Schematic process of the growth mechanism for hierarchically porous SOD via solvent-free method. Reproduced from Ref. [42] with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.](/media/item_content/202103/figure2-605b27c0462cf.png)

Figure 2. Schematic process of the growth mechanism for hierarchically porous SOD via the solvent-free method. Reproduced from Ref. [42] with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

In addition to the soft templates mentioned above, hard templates were also feasible. Ren et al. [19] found that after the addition of CaCO3 in the solid raw materials as a hard template followed by acid treatment, ZSM-5 crystals possessed macropores about 100 nm. Moreover, Li et al. [43] used graphene oxide (GO) sheets as a hard template to prepare hierarchically porous ZSM-5. After removing the template, the sizes of the micropores and mesopores were about 0.6 nm and 2–60 nm, respectively.

4.2. Up–Down Strategy

Organic compounds were usually served as a secondary template or porogen to assist the formation of mesopores or macropores [44] via a bottom-up strategy that was not environmentally friendly and economical. The up-down strategy could eliminate the use of mesoporogen.

Hierarchically porous HY zeolites were prepared by Nichterwitz et al. [45] using carbochlorination in solvent-free conditions. HY zeolites were ground with furfuryl alcohol (FA) and ethanol (EtOH) followed by temperature-programmed carbonized and carbochlorination. As the chlorination temperature increased, the total pore volume and mesopore volume increased, while the micropore volume decreased. Meanwhile, the pore size became larger. The apertures of samples chloridized at 673 K and 773 K were 4 and 7 nm, respectively. For the samples chloridized at 873 K, the pore size distributed from 6 to 16 nm. While chloridized at 973 and 1073 K, samples showed two main pore sizes of 10 and 16 nm. Carbon content in composite, chlorination time and Si/Al ratio might also affect the physicochemical properties of zeolites. Carbochlorination can double the pore volume, while the surface area and crystallinity of the material can be maintained under optimal conditions.

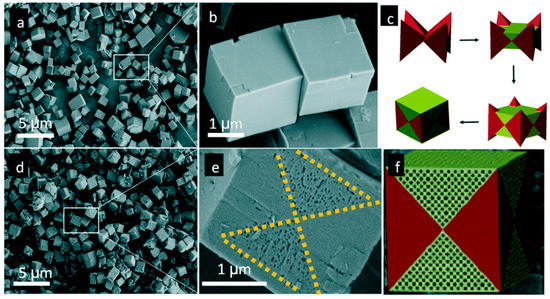

Though carbochlorination was effective, its conditions were relatively severe (around 800 °C). Dealumination or desilication by acids or bases were adopted alternatively. Hierarchically porous SAPO-34 zeolites were synthesized by grinding SAPO-34 with solid oxalic acid followed by heating at 373 K for 6 h [46]. Interestingly, the surface of the product presented a clear pattern of butterfly pores with a pore size of 60–100 nm. The formation of butterfly pattern SAPO-34 was related to the synthesis process of the cubic SAPO-34 and the following etching process. In the early stages of the synthesis of cubic SAPO-34, crystals had preferentially grown in a specific direction, thus forming a specific crystal morphology, which consisted of eight cone parts and a void around the center. Then, the void was filled along with crystal growth to form a perfect cube (Figure 3c). However, the energy of subsequently filled parts was unstable. Therefore, it was preferable to etch them after treatment with solid oxalic acid to form a layered structure with a butterfly pattern.

![Figure 3. SEM images of SAPO-34 (a,b) before and (d,e) after solid oxalic acid treatment, (c) schematic drawing of the growth of SAPO-34, and (f) the drawing of the morphology of treated SAPO-34. Reproduced from Ref. [46] with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.](/media/item_content/202103/figure3-605b2bc13708f.png)

Figure 3. SEM images of SAPO-34 (a,b) before and (d,e) after solid oxalic acid treatment, (c) schematic drawing of the growth of SAPO-34, and (f) the drawing of the morphology of treated SAPO-34. Reproduced from Ref. [46] with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Hierarchically porous SAPO-11 zeolites were also prepared by this method [47]. It was discovered that high crystallinity and uniform morphology were retained after etching by solid oxalic acid. In addition, more (002) crystal planes were exposed meaning more acidic sites could be provided. The results of N2 adsorption-desorption showed that though the mesoporous structure (4 nm) was dominant, all samples contained microporous (0.5 nm) and mesoporous structures.

5. Synthesis of Zeolites with Different Morphologies

It was reported that the morphologies of zeolites might improve mass transfer because the physicochemical properties of zeolites could be strongly affected by their morphologies [48][49][50].

Wu et al. [51] synthesized a hollow zeolite shell assembled by ZSM-5 with a short b-axis by the solvent-free method. SiO2 spheres were used as silica sources, with prefabricated ZSM-5 and NH4F as Al source and mineralizer, respectively. In-situ XRD analysis and SEM were performed to analyze the morphological and structural evolutions. After crystallizing for 1 h, the peaks of MFI significantly weakened, indicating that prefabricated ZSM-5 was broken down into small segments. Meanwhile, the peak at 18.68° was associated with (NH4)2SiF6, inferring that NH4F reacted with silica from the substrate and prefabricated ZSM-5 which roughen the surface of the silica ball (Figure 4b,c). No (NH4)3AlF6 peaks appeared in all samples, indicating that the confined Al source prevented coordination between Al and the fluoride species giving a well-preserved acidic framework Al in the final products. After crystallizing for 2–4 h, SiF62− species were gradually condensed to Si(OSi)4 in the initial stage of MFI crystallization (Figure 4d). As the crystallization was prolonged, SiF62− species were completely converted into ZSM-5 (Figure 4e). During crystallization, silica was migrated to the surface leading to the formation of the hollow structure.

![Figure 4. (a) In-situ XRD patterns, (b–e) SEM images, and (f–i) corresponding illustration of hollow ZSM-5 shell at different crystallization times. Reproduced from Ref. [51] with permission from 2019 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.](/media/item_content/202103/figure4-605b2d374a2d6.png)

Figure 4. (a) In-situ XRD patterns, (b–e) SEM images, and (f–i) corresponding illustration of hollow ZSM-5 shell at different crystallization times. Reproduced from Ref. [51] with permission from 2019 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

In hydrothermal synthesis, additives were often used to adjust crystal morphology [52], which were also used in the solvent-free method. Zhang et al. [53] synthesized silicalite-1 zeolites by the solvent-free method with the assistance of NH4F. It was discovered that the addition of NaOH (NaOH/SiO2 = 0.09) could reduce the crystal sizes and the samples were in a morphology of coffin which had a long c-axis. As the content of NaOH increased (NaOH/SiO2 = 0.19), the morphology of crystals became spherical.

Chen et al. [54] synthesized SAPO-5 zeolites with plate-like morphology with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) as a surfactant through the solvent-free method. It was discovered that CTAB strongly suppressed the growth of SAPO-5 crystal in the (002) direction. The morphology of the product was spherical in the absence of CTAB.

When the amount of CTAB added increased, the morphology of the zeolite gradually changed from a spherical shape to a discus-like shape, and finally to a sheet shape. Different from the formation of self-assembly micelles in the solvent, CTAB could selectively adsorb on certain surfaces of the SAPO-5, thereby inhibiting the growth in the (002) direction.

Yu et al. [55] synthesized well-crystallized hollow fibers composed of c-axis-oriented ZSM-5 by the solvent-free method with quartz fiber as silicon source and NH4HCO3 as additives. During the process of crystallization, the silicon source continuously migrated to the surface of the quartz fiber and crystallized on the surface to form ZSM-5, giving a hollow morphology. Moreover, the length of the c-axis of ZSM-5 was adjustable by controlling the amount of NH4HCO3. NH3 decomposition by NH4HCO3 could inhibit the growth of (010) surface. Liu et al. [56] also synthesized c-axis-oriented ZSM-5 by the solvent-free method in the presence of urea. It was discovered that NH3 decomposition by urea suppressed the growth of b-axis orientation and developed the growth in the c-axis direction.

Graphene oxide (GO) sheets were also used as an additive to synthesize c-axis-oriented ZSM-5 by the solvent-free method [43]. It was discovered that GO sheet adsorbed more stably on (010) and (100) planes than on (101) planes leading to the growth restriction of the (010) and (100) facets. So, ZSM-5 crystals had an elongated shape along the c-axis, which was analogous to the conclusion of hydrothermal synthesis [57]. Moreover, GO could prevent the aggregation of the ZSM-5 crystals during the synthesis. Furthermore, the addition of GO sheets led to the formation of hierarchical pore structures, which is conducive to mass transfer and product selectivity [58].

6. Mechanism on Zeolite Synthesis

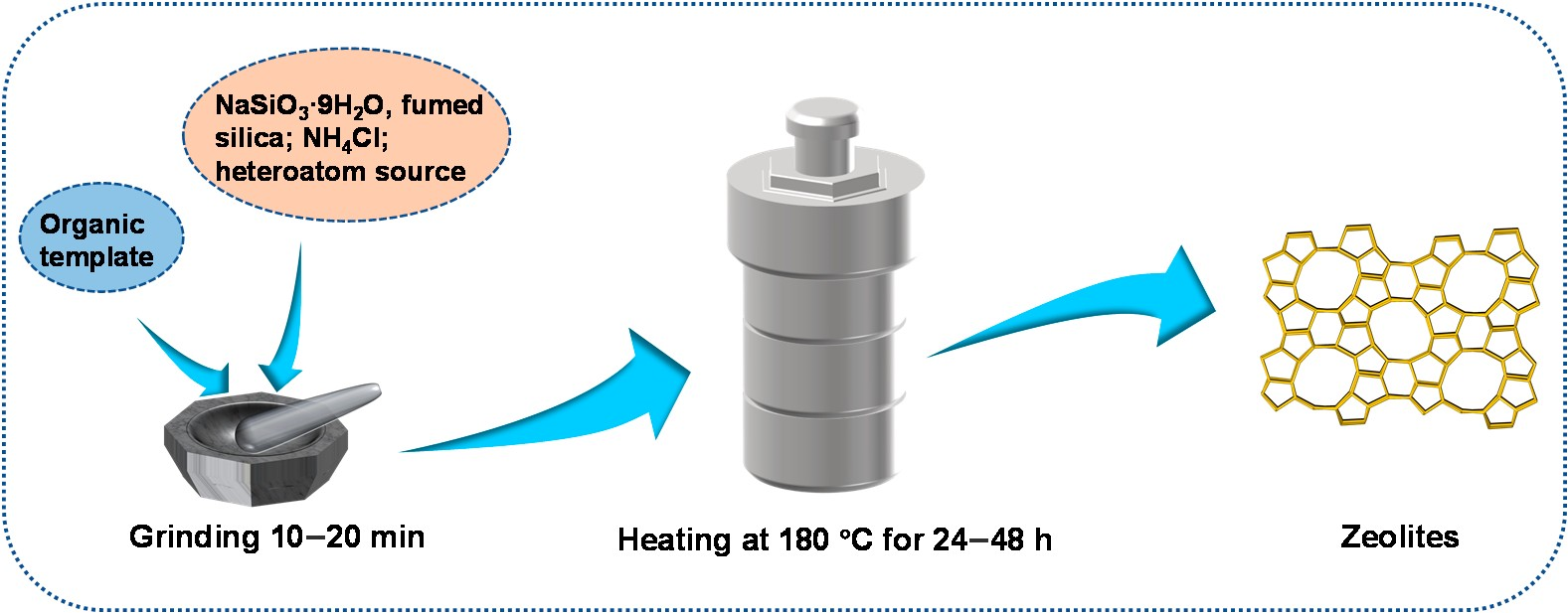

Xiao et al. [19] first reported the solvent-free method in 2012. Typically, the solid raw materials (NaSiO3·9H2O, fumed silica, NH4Cl, organic SDA and heteroatom source such as Al and Fe) were ground for 10–20 min without the addition of any water. Then the mixture was heated in an autoclave at 453 K for 24–72 h. Figure 5 is a schematic diagram of the solvent-free method.

Figure 5. Synthesis of zeolites through the solvent-free method.

They found that the sample after grinding showed diffraction peaks of NaCl, though NaCl was not one of the raw materials. It was believed that NaCl was obtained by the reaction between Na2SiO3 and NH4Cl, which was consistent with the research of Nada [27]. Ammonia, metasilicic acid and water were also generated in the process of grinding. Simultaneously, the trace amount of water from the hydrated raw material acted as a medium that diffused and intimately mixed Si, Al and O ions, promoting the growth of ZSM-5 crystals. Xiao et al. [19] found that that the ultraviolet Raman signal attributed to the template was significantly weakened after heating at 453 K for 2 h, indicating that the template was highly dispersed on the amorphous carrier. Moreover, the amorphous intermediate sample heating for 2 h exhibited a pore size of 0.8 nm, while there was no porosity in the intermediate materials at a similar stage in hydrothermal synthesis.

It was worth mentioning that when all raw materials do not contain crystal water, ZSM-5 cannot be obtained by solvent-free methods [59]. Trace water was a key factor for zeolite crystallization in the solvent-free route, which was similar to the role of “catalyst” that promoted depolymerization and condensation of silica species. To prove this point of view, solvent-free zeolite synthesis was performed from anhydrous solid raw materials with NH4F as a mineralizer, and a zeolite product with high crystallinity was obtained [24]. At the beginning of the synthesis process, SiF62− species produced by the reaction of silica and NH4F were observed. After crystallization for 2.5 h, SiF62− species were condensed to Si(OSi)4, and F− was released. It was suggested that F− could serve as a “catalyst” for depolymerization and condensation of silica species, similar to water.

The crystallization process of the ground mixture was demonstrated by NaA zeolite [60]. The result of UV-Raman characterization demonstrated that after 24 h of aging at room temperature, the ground sample showed a weak band at 498 cm−1, which was related to the four-membered rings (4R). It was consistent with the peak position of the sample after crystallization at 80 °C for 2 h. However, the as-ground sample did not exhibit the same band. This indicated that the raw materials could interact with each other at room temperature after grinding, and spontaneously form a four-membered rings (4R) structure. With the increase in crystallization time, in addition to 4R, six-membered rings (6R) and eight-membered rings (8R) appeared, and the intensities of these signals increased. The results of 27Al MAS NMR, 29Si NMR and 27Al 2D MQMAS NMR further showed that 4R in the parent mixture were double four-membered rings (D4R) rather than a single four-membered ring (S4R). After 4 h of crystallization, all D4R units had been converted into LTA structure. It can be concluded that hydrated silica and sodium aluminate would interact with each other spontaneously, leading to the formation of D4R, which could be further assembled or rearranged into NaA crystals in the absence of water solvent, as shown in Figure 6.

![Figure 6. The proposed route for the synthesis of zeolite A in the absence of solvent. Reproduced from Ref. [60] with permission from 2016 Elsevier Inc.](/media/item_content/202103/figure6-605b2fb6348d2.bmp)

Figure 6. The proposed route for the synthesis of zeolite A in the absence of solvent. Reproduced from Ref. [60] with permission from 2016 Elsevier Inc.

7. Applications of Solvent-Free Zeolite

Although the solvent-free method was a convenient method to synthesize zeolites, the performance of synthesized zeolite was unknown, which needed to be tested in practice. Wang et al. [61] successfully synthesized CHA zeolite SSZ-13 with N,N,N- dimethylethylcyclohexylammonium bromide as a template by the solvent-free method. The specific surface area and pore volume of the product were 584 m2·g−1 and 0.27 cm3·g−1, respectively, which was close to those of SSZ-13 prepared by a hydrothermal route. The solvent-free SSZ-13 was used in the methanol-to-olefins (MTO) reaction at 623 K. It was found that the conversion rate of methanol was close to 100%, and the selectivity of propylene was about 35%, which was similar to SSZ-13 synthesized by a hydrothermal method.

Liu et al. [62] synthesized a hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolite with high crystallinity, adjustable Si/Al ratio for methanol to gasoline (MTG) conversion by the solvent-free method [63]. Activated carbon was blended with other raw materials and ground for 20 s to form the hierarchical pore structure. Si/Al ratio was facilely adjusted from 20 to 100 by controlling the amount of NaAlO2 added. Solvent-free ZSM-5 exhibits excellent MTG performance, with a methanol conversion rate close to 100%, C5+ selectivity higher than 60%, and a lifetime of 350 h.

Zhang et al. [63] also synthesized ZSM-5 by a solvent-free method applied in MTO reaction and compared it with ZSM-5 prepared by the traditional hydrothermal method. The characteristic diffraction peaks of ZSM-5 appeared when the crystallization time reached 3 h. When it reached 6 h, the crystallinity was similar to the traditional ZSM-5. When the crystallization time was 30 h and the Si/Al ratio of raw materials was 150 under the solvent-free conditions, the selectivity of the catalyst to propylene was as high as 50%, and the catalyst life was as long as 9 h, which were much better than those of the traditional ZSM-5 zeolites with propylene selectivity of 38.9% and catalyst life of 3 h. Moreover, the presence of mesoporous was confirmed by high-resolution TEM, which was favorable for the mass transfer. More interestingly, these mesopore size distributions were adjustable by controlling the crystallization time.

8. Conclusions and Perspective

Compared with the traditional hydrothermal method, the solvent-free synthesis method displays the following prominent advantages [19]. (1) High yields—a large amount of solvent used in traditional hydrothermal synthesis will dissolve partial nutrients such as silicate or aluminate, reducing the yield of the product. (2) High single-autoclave yield—the solvent occupies most of the space in the autoclaves during the hydrothermal synthesis process, otherwise, the autoclave can hold more solid raw materials through the solvent-free method; as such, the single-autoclave yield is greatly increased. (3) Fewer pollutants— solvents are not used in solvent-free methods, reducing wastewater emissions efficiently. (4) Low crystallization pressure—since solvents are not adopted in the solvent-free method, the autogenous pressure generated at high temperatures is relatively lower, which makes the requirements for equipment moderate. (5) High space-time yields—the long-term aging process does not exist in the solvent-free method, so the space-time yield is greatly increased. Table 1 lists the zeolites synthesized by the solvent-free method, including silica, aluminosilicate, and aluminophosphate zeolites.

Table 1. Zeolites synthesized by the solvent-free method.

| Zeolite | IZA Code | Dimension | Crystal System | Space Group | Reference |

|

ZSM-5 |

MFI |

3 |

orthorhombic |

P n m a |

[16][19][24][43][51][64][65][66] |

|

silicalite-1 |

MFI |

3 |

orthorhombic |

P n m a |

|

|

Beta |

*BEA |

3 |

tetragonal |

P 41 2 2 |

|

|

Y |

FAU |

3 |

cubic |

F d 3 m |

[19] |

|

ZSM-39 |

MTN |

0 |

cubic |

F d 3 m |

[19] |

|

EU-1 |

EUO |

1 |

orthorhombic |

C m m e |

[24] |

|

ZSM-22 |

TON |

1 |

orthorhombic |

C m c m |

[24] |

|

Mordenite |

MOR |

2 |

orthorhombic |

C m c m |

|

|

TS-1 |

MFI |

3 |

orthorhombic |

P n m a |

[68] |

|

sodalite |

SOD |

0 |

cubic |

I m 3 m |

|

|

A |

LTA |

3 |

cubic |

P m 3 m |

[60] |

|

SAPO-34 |

CHA |

3 |

trigonal |

R 3 m |

[28] |

|

SAPO-43 |

SOD |

0 |

cubic |

I m 3 m |

[28] |

|

SAPO-20 |

GIS |

3 |

tetragonal |

I 41/a m d |

[28] |

|

SAPO-11 |

AEL |

1 |

orthorhombic |

I m m a |

|

|

SAPO-5 |

AFL |

1 |

hexagonal |

P 6/m c c |

|

|

SSZ-13 |

CHA |

3 |

trigonal |

R 3 m |

|

|

ITQ-12 |

ITW |

2 |

monoclinic |

C1 2/m 1 |

[72] |

|

ITQ-13 |

ITH |

|

orthorhombic |

A m m 2 |

[72] |

|

ITQ-17 |

BEC |

3 |

tetragonal |

P 42/m m c |

[72] |

|

Cancrinite |

CAN |

1 |

hexagonal |

P 63/m m c |

[73] |

|

Na-EMT |

EMT |

3 |

hexagonal |

P 63/m m c |

[74] |

|

SSZ-39 |

AEI |

3 |

orthorhombic |

C m c m |

[75] |

In view of the above factors, the solvent-free route will be of great significance to the industrial production of zeolites in the future. Combined with the template-free method, the cost of the solvent-free method will also be reduced, making it more competitive than hydrothermal synthesis. However, in the solvent-free process, the template-free method can only be used to synthesize a few special zeolites, and most zeolites still require SDA. Although the use of zeolite seeds can expand the synthesis range of template-free and solvent-free methods, the preparation of seed crystals is still a relatively complicated step. Hence, how to synthesize zeolite solvent-free without using templating agents and zeolite seeds is the focus of future research.

In addition, insights into the mechanism of the solvent-free synthesis of zeolite are still necessary, especially regarding the interaction between SDA and framework. The current research results show that the primary and secondary structural units play a vital role in the crystallization process of zeolite, but the interaction between the template and the zeolite is not well understood. Different from the hydrothermal method, there is microporosity in the amorphous intermediate materials by solvent-free method indicating a distinguishable mechanism on the crystallization of zeolites. There is still a lack of appropriate theories to explain how SDA directs amorphous silica to a specific zeolite structure.

沸石,一种具有优秀的水热稳定性的结晶微孔材料的,是最重要的工业无机固体之一[ 1,2,3,4 ],已在离子交换,吸附,分离,医药领域被广泛应用,光电子和催化[ 5,6,7,8,9,10,11 ]。沸石可以从天然矿石获得或人工合成。通常,人工合成的沸石具有较高的结晶度,并广泛用于离子交换剂和催化剂[ 12]。自Barrer和Milton通过模拟自然条件提出水热合成技术以来,水热合成已成为制备沸石的常规方法[ 13 ]。

In summary, the solvent-free method is a simplified, efficient, high-yield, and low-cost methodology for the preparation of zeolites but is not limited to zeolites. A small amount of water was a critical parameter for zeolite formation. By combining the advantages of solvent-free and template-free synthesis, a large-scale application in zeolite synthesis would have great potential in the industry.

然而,水热法不可避免地使用大量的水作为溶剂。尽管可以认为水是无害的,但过量添加水会引起许多问题,其中包括:(1)用水填充过多会产生较高的自生压力,这会导致设备安全问题;(2)高压釜的空间利用效率低,产品收率低;(3)来自废水的污染[ 14 ]。因此,在无水条件下合成的沸石降低或从合成过程中除去的溶剂是具有重要意义,并且符合绿色化学[概念15,16 ]。

Author Contributions: Writing—review and editing, J.M.; supervision, A.D., X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

开拓性研究挑战了沸石合成过程中水的必要性。1990年,Xu等。[ 17 ]开发了一种新的合成沸石的气相传输(VPT)方法,成功地避免了在结晶过程中使用大量的水溶剂。1994年,Althoff等人。[ 18 ]使用氟化铵代替水蒸气,并证明在结晶过程中不需要水的存在。

Funding: This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFC1907602), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21878330), the National Science and Technology Major Project (No. 2019YFC1907700) and the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) Office of Sponsored Research (OSR) under Award (No. OSR-2019-CPF-4103.2).

尽管VPT方法可以解决一些问题,但在制备干凝胶的过程中仍然需要使用许多溶剂。2012年,Xiao等人。[ 19 ]报道了一种无溶剂的方法,该方法通过机械研磨和加热原料而不添加额外的水来制备不含溶剂的沸石。在无溶剂工艺中,没有明显的游离水或使用其他溶剂代替水。这并不是说系统中没有水。

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

2.汽相运输技术

针对由沸石合成中过量使用水引起的一系列问题,开发了干凝胶转化(DGC)和气相传输(VPT)技术[ 20 ]。干凝胶样品升高的温度和自生压力下放置在结构导向剂(SDA)溶液上方,并用水和胺蒸气反应在密封的高压釜(图1)[ 17,21]。ZSM-5在180–200°C下成功合成5–7天。将水和胺的混合溶液从固相中分离出来,这有助于溶液的回收,并且可以重复使用以避免废水处理。而且,有机胺的成本占据了沸石合成的很大一部分,这降低了产物的最终成本。

图1.通过气相传输(VPT)方法合成沸石。

为了探索在VPT方法中水的必要性,Althoff等人。[ 18 ]在650°C下处理前体24小时以形成干粉。在随后的结晶过程中,他们使用氟化铵代替直接使用水蒸气,并逐渐降低了系统中的水含量,最终形成了绝对干燥的混合物。他们发现,在极端无水的情况下,沸石仍能成功合成,表明结晶过程不需要水。他们认为SiF 4是由无定形前体的转化形成的流动相。

Kim等。[ 22 ]和Matsukata等。[ 23 ]改进了相关研究,并证明了气相传输技术可用于合成各种沸石,例如MFI,FER,MOR等。此外,VPT法可以扩大沸石形成的组成。

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

3.沸石的无溶剂合成

VPT技术解决了在沸石结晶过程中过量使用水的问题。通过VPT的成功,可以提出在沸石的结晶过程中不需要溶剂。但是,值得注意的是,大量的水对于凝胶的制备至关重要。为了解决这些问题,Xiao等人。[ 19 ]开发了一种基于机械化学的无溶剂方法。使用该方法成功合成了几种具有MFI,MOR,FAU,SOD和* BEA骨架的最重要的工业沸石。无溶剂的ZSM-5的比表面积,孔体积和孔径为276米2 ·克-1,0.13厘米3 ·克-1和0.53 nm。有趣的是,沸石种子可以代替SDA来指导无溶剂条件下β沸石的合成,这可以大大减少SDA的使用。消除使用昂贵且有毒的有机模板和过量溶剂的使用,可以减少合成沸石的成本,并减少煅烧模板剂和废水排放所造成的环境污染,这将是以环保和经济的方式合成沸石的最终目标。

肖等。[ 24 ]在NH 4 F的辅助下,结合无模板方法对无溶剂合成进行了扩展研究。最终,成功合成了silicalite-1,Beta,EU-1和ZSM-22沸石。然而,通过这种方法仍然需要沸石种子。因此,如何避免使用沸石种子将成为下一个研究重点。

高等。[ 25 ]在无有机模板的情况下,通过无溶剂方法成功地在实验室规模条件下合成了高结晶度的MOR沸石(通过1 L高压釜生产650 g MOR)。在473 K下合成48 h的MOR分子筛的比表面积和孔容分别为392.1 m 2 ·g -1和0.314 cm 3 ·g -1,与常规方法合成的分子筛(397.9 m 2 · g -1)相似。 g -1和0.093 cm 3 ·g -1)。尽管孔体积比常规的MOR沸石大得多,但相对结晶度仅为70%,需要进一步改进。值得注意的是,当将SBA-15用作二氧化硅源时,出现MFI结构,这表明可以通过无溶剂和无模板方法合成MFI结构。Nada等。[ 26,27]进行了相关研究;他们发现通过改变原料比例可以合成不同的沸石。混合物中较高的Si含量和较低的Na含量有利于ZSM-5沸石,而较高的Na和Al含量有利于丝光沸石,这与合成观察结果相似。当前,通过无溶剂方法,在不使用模板和沸石种子的情况下,仅可以合成少量沸石。

除了合成硅铝酸盐外,无溶剂方法还扩展到了铝磷酸盐的制备。Jin等。[ 28 ]报道了在合成硅铝磷酸盐,铝磷酸盐和含杂原子的铝磷酸盐沸石中使用无溶剂方法。无溶剂SAPO-34的比表面积和孔体积为459 m 2 ·g -1和0.27 cm 3 ·g -1, 分别。无溶剂的SAPO-34的转化率接近100%。总产率为88.9%,接近于通过传统方法制备的SAPO-34的产率(91.3%)。此外,所得SAPO-34表现出分层的多孔结构,这有利于提高丙烯和丁烯的选择性并降低乙烯的选择性。

值得一提的是,杂原子可以被方便地掺入到沸石的由无溶剂方法,该方法已在工业上被广泛使用[框架29,30,31,32,33 ]。通常,通过在水热条件下进行多次离子交换来合成金属交换的沸石,这很复杂并且也产生大量废水。使用无溶剂方法合成杂原子沸石可以克服这些缺点。Ma等。[ 34 ]通过机械混合,研磨和加热原材料(铝硅酸盐凝胶,模板和金属-胺配合物)的无溶剂方法,在一锅中合成了杂原子沸石。在27Cu-SSZ-13的Al MAS NMR光谱表明样品中没有骨架外的铝物种,这与常规的水热法非常吻合。而且,Cu-SSZ-13的产率为98.1%,远高于传统的离子交换(55.6%)[ 35 ]。

无溶剂方法也可以应用于金属掺杂的硅铝磷酸盐沸石。Wang等。[ 36 ]合成的纳米级镁通过无溶剂方法掺入SAPO-34。在此过程中,层状粘土矿物(一种廉价的富含Mg的铝硅酸盐)被用作Mg,Si和Al的来源。此外,它还用作硬模板,可显着减小晶体尺寸。该产物的Mg含量高达6.65%,并且晶体尺寸小(50nm),这有利于传质。Mg含量为3%的沸石显示出几乎100%的氯甲烷转化率和88.1%的高轻烯烃选择性。

Data Availability Statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

4.层级孔隙结构的形成

沸石因其易于调节的理化性质而受到广泛关注。然而,微孔的扩散限制将限制反应物和产物的传质,从而降低反应动力学。因此,分级多孔结构对于大分子反应是必需的。常见的是,分级多孔沸石的合成方法分为自下而上和自上而下的方法[ 37,38,39 ]。在水热合成过程中,使用硬模板或软模板的不同方法被归类为自下而上的方法,而通过脱铝和脱硅处理沸石的方法被归类为自上而下的方法[ 39]。在此,该概念仍在无溶剂方法中使用。

4.1。自下而上的策略

Jin等。[ 40 ]通过无溶剂方法合成了分层多孔的铝磷酸盐基沸石。在合成具有AEL结构的沸石(APO-11)时,在室温下研磨磷酸二正丙胺(DPA·H 3 PO 4)和勃姆石并在200°C下加热。在600°C下煅烧4 h后,样品的相对压力在10 -6 –0.01处急剧增加,这可能是由于微孔的填充所致。同时,在0.45-0.95的相对压力下可以观察到磁滞回线,表明样品中存在中孔和大孔。DPA·H 3 PO 4用作有机模板和磷源,避免了合成过程中胺的挥发。盛等。[ 41 ]发现,在结晶过程中,大量的气态二正丙胺(DPA)分子可以迅速从DPA·H 3 PO 4中释放出来,这可以作为中孔形成的“致孔剂”。

Zeng等。[ 42 ]通过无溶剂方法以有机硅烷作为介孔生成剂合成了分级多孔SOD沸石。图2阐明了通过无溶剂方法分层生长SOD的生长机理的示意性过程。研磨后结晶之前,样品形成无定形固体。结晶2小时后,可以观察到由无定形聚集体形成的蠕虫状中孔通道。结晶4小时后,检测到空隙或孔洞,这将导致形成细胞状SOD沸石。归因于有机硅烷表面活性剂,合成的SOD沸石表现出小的中孔(4.6 nm),而归因于颗粒间空隙的中观大孔(20-55 nm)。

图2.通过无溶剂方法分层多孔SOD的生长机理示意图。转载自参考文献。[ 42 ]经英国皇家化学学会许可。

除了上面提到的软模板,硬模板也是可行的。任等人。[ 19 ]发现,在固体原料中添加CaCO 3作为硬模板,然后进行酸处理后,ZSM-5晶体具有约100 nm的大孔。此外,李等。[ 43 ]使用氧化石墨烯(GO)片作为硬模板来制备分层多孔的ZSM-5。除去模板后,微孔和中孔的大小分别约为0.6 nm和2-60 nm。

4.2。上下策略

有机化合物通常被用作辅助模板或致孔剂,以通过不环保且不经济的自下而上的策略来协助中孔或大孔的形成[ 44 ]。上下策略可以消除中孔致病菌的使用。

Nichterwitz等人制备了分层多孔的HY沸石。[ 45]在无溶剂的条件下使用碳氯化法。用糠醇(FA)和乙醇(EtOH)研磨HY沸石,然后进行程序升温的碳化和碳氯化反应。随着氯化温度的升高,总孔体积和中孔体积增加,而微孔体积减少。同时,孔径变大。在673 K和773 K下氯化的样品的孔径分别为4和7 nm。对于在873 K下氯化的样品,孔径分布在6至16 nm之间。在973和1073 K下进行氯化时,样品显示出两个主要的孔径,分别为10和16 nm。复合材料中的碳含量,氯化时间和Si / Al比也可能影响沸石的理化性质。碳氯化可以使孔体积增加一倍,

尽管碳氯化法是有效的,但其条件相对较苛刻(约800°C)。可替代地采用通过酸或碱的脱铝或脱硅。通过将SAPO-34与固体草酸一起研磨,然后在373 K下加热6 h,可以合成出多孔的SAPO-34分子筛[ 46]。有趣的是,产品表面呈现出清晰的蝴蝶孔图案,孔径为60–100 nm。蝶形图案SAPO-34的形成与立方SAPO-34的合成过程以及随后的蚀刻过程有关。在立方SAPO-34合成的早期阶段,晶体优先向特定方向生长,因此形成了特定的晶体形态,该形态由八个锥体部分和围绕中心的空隙组成。然后,将空隙与晶体生长一起填充以形成理想的立方体(图3c)。但是,随后填充的零件的能量不稳定。因此,优选在用固体草酸处理之后将它们蚀刻以形成具有蝴蝶图案的层状结构。

图3.固体草酸处理之前和之后(d,e)的SAPO-34的SEM图(a,b),(c)SAPO-34的生长示意图和(f)处理过的SAPO-34。转载自参考文献。[ 46 ]经英国皇家化学学会许可。

分层多孔的SAPO-11沸石也可以通过这种方法制备[ 47 ]。发现通过固体草酸蚀刻后,保留了高结晶度和均匀的形态。另外,更多的(002)晶面被暴露,这意味着可以提供更多的酸性位点。N 2吸附-解吸的结果表明,尽管介孔结构(4 nm)占主导,但所有样品均含有微孔(0.5 nm)和介孔结构。

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Corma, A.; Inorganic solid acids and their use in acid-catalyzed hydrocarbon reactions. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 559-614, 10.1021/cr00035a006.

- Corma, A.; From microporous to mesoporous molecular sieve materials and their use in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 2373–2420, 10.1021/cr960406n.

- Davis, M.E.; Ordered porous materials for emerging applications. Nature 2002, 417, 813-821, 10.1038/nature00785.

- Li, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, J.; Applications of zeolites in sustainable chemistry. Chem. 2017, 3, 928–949, 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.10.009.

- Amorim, R.; Vilaça, N.l.; Martinho, O.; Reis, R.M.; Sardo, M.; Rocha, J.o.; Fonseca, A.n.M.; Baltazar, F.t.; Neves, I.C.; Zeolite structures loading with an anticancer compound as drug delivery systems. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 25642–25650, 10.1021/jp3093868.

- Corma, A.; Iborra, S.; Velty, A.; Chemical routes for the transformation of biomass into chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2411–2502, 10.1021/cr050989d.

- Tao, Y.; Kanoh, H.; Kaneko, K.; ZSM-5 monolith of uniform mesoporous channels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6044–6045, 10.1021/ja0299405.

- Ohlin, L.; Bazin, P.; Thibault-Starzyk, F.; Hedlund, J.; Grahn, M.; Adsorption of CO2 , CH4 , and H2O in zeolite ZSM-5 studied using in situ ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 16972–16982, 10.1021/jp4037183.

- Valtchev, V.; Tosheva, L.; Porous nanosized particles: Preparation, properties, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 6734–6760, 10.1021/cr300439k.

- Fiorillo, A.S.; Tiriolo, R.; Pullano, S.A.; Absorption of urea into zeolite layer integrated with microelectronic circuits. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 214–217, 10.1109/TNANO.2014.2378892.

- Fiorillo, A.; Pullano, S.; Rudenko, S.; Stetsenko, M.; Maksimenko, L.; Krishchenko, I.; Synyuk, V.; Antireflection properties of composite zeolite gold nanoparticles film. Electron. Lett. 2018, 54, 370–372, 10.1049/el.2017.4647.

- Johnson, E.B.G.; Arshad, S.E.; Hydrothermally synthesized zeolites based on kaolinite: A review . Appl. Clay. Sci. 2014, 97–98, 215–221, 10.1016/j.clay.2014.06.005.

- Rabenau, A.; The role of hydrothermal synthesis in preparative chemistry.. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1985, 24, 1026–1040, 10.1002/anie.198510261.

- Meng, X.; Xiao, F.-S.; Green routes for synthesis of zeolites. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1521–1543, 10.1021/cr4001513.

- Hari, P.; Rao, P.; Matsukata, M.; Dry-gel conversion technique for synthesis of zeolite BEA. Chem. Commun. 1996, 12, 1441–1442, 10.1039/CC9960001441.

- Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Qi, G.; Guo, Q.; Pan, S.; Meng, X.; Xu, J.; Deng, F.; Fan, F.; Feng, Z. S; et al. ustainable synthesis of zeolites without addition of both organotemplates and solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4019–4025, 10.1021/ja500098j.

- Xu, W.; Dong, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Wu, F.; A novel method for the preparation of zeolite ZSM-5. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1990, 10, 755–756, 10.1039/c39900000755.

- Althoff, R.; Unger, K.; Schüth, F.; Is the formation of a zeolite from a dry powder via a gas phase transport process possible? . Microporous Mater. 1994, 2, 557–562, 10.1016/0927-6513(94)E0027-R.

- Ren, L.; Wu, Q.; Yang, C.; Zhu, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; Meng, X.; Xiao, F.S.; Solvent-free synthesis of zeolites from solid raw materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15173–15176, 10.1021/ja3044954.

- Naik, S.P.; Chiang, A.S.; Thompson, R.; Synthesis of zeolitic mesoporous materials by dry gel conversion under controlled humidity. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 7006–7014, 10.1021/jp034425u.

- Matsukata, M.; Ogura, M.; Osaki, T.; Rao, P.R.H.P.; Nomura, M.; Kikuchi, E.; Conversion of dry gel to microporous crystals in gas phase. Top. Catal. 1999, 9, 77–92, 10.1023/A:1019106421183.

- Kim, M.-H.; Li, H.-X.; Davis, M.E.; Synthesis of zeolites by water-organic vapor-phase transport. Microporous Mater. 1993, 1, 191–200, 10.1016/0927-6513(93)80077-8.

- Nishiyama, N.; Ueyama, K.; Matsukata, M.; Synthesis of defect-free zeolite-alumina composite membranes by a vapor-phase transport method. Microporous Mater. 1996, 7, 299–308, 10.1016/S0927-6513(96)00053-3.

- Wu, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Ding, L.; Gao, P.; Wang, X.; Pan, S.; Bian, C.; Meng, X.; Xu, J.; et al.et al. Solvent-free synthesis of zeolites from anhydrous starting raw solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1052–1055, 10.1021/ja5124013.

- Gao, W.; Amoo, C.C.; Zhang, G.; Javed, M.; Mazonde, B.; Lu, C.; Yang, R.; Xing, C.; Tsubaki, N.; Insight into solvent-free synthesis of MOR zeolite and its laboratory scale production. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 280, 187–194, 10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.01.041.

- Nada, M.H.; Larsen, S.C.; Gillan, E.G.; Mechanochemically-assisted solvent-free and template-free synthesis of zeolites ZSM-5 and mordenite. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 3918–3928, 10.1039/C9NA00399A.

- Nada, M.H.; Gillan, E.G.; Larsen, S.C.; Mechanochemical reaction pathways in solvent-free synthesis of ZSM-5. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 276, 23–28, 10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.09.009.

- Jin, Y.; Sun, Q.; Qi, G.; Yang, C.; Xu, J.; Chen, F.; Meng, X.; Deng, F.; Xiao, F.S.; Solvent-free synthesis of silicoaluminophosphate zeolites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9172–9175, 10.1002/anie.201302672.

- Joshi, R.; Zhang, G.; Miller, J.T.; Gounder, R.; Evidence for the coordination–insertion mechanism of ethene dimerization at nickel cations exchanged onto beta molecular sieves. Acs Catal. 2018, 8, 11407–11422, 10.1021/acscatal.8b03202.

- Fickel, D.W.; Lobo, R.F.; Copper coordination in Cu-SSZ-13 and Cu-SSZ-16 investigated by variable-temperature XRD. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 1633–1640, 10.1021/jp9105025.

- Narsimhan, K.; Michaelis, V.K.; Mathies, G.; Gunther, W.R.; Griffin, R.G.; Roman-Leshkov, Y.; Methane to acetic acid over Cu-exchanged zeolites: Mechanistic insights from a site-specific carbonylation reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1825–1832, 10.1021/ja5106927.

- Pappas, D.K.; Borfecchia, E.; Dyballa, M.; Pankin, I.A.; Lomachenko, K.A.; Martini, A.; Signorile, M.; Teketel, S.; Arstad, B.; Berlier, G.; et al. Methane to methanol: Structure–activity relationships for Cu-CHA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14961–14975, 10.1021/jacs.7b06472.

- Ryu, T.; Ahn, N.H.; Seo, S.; Cho, J.; Kim, H.; Jo, D.; Park, G.T.; Kim, P.S.; Kim, C.H.; Bruce, E.L.; et al. Fully copper-exchanged high-silica LTA zeolites as unrivaled hydrothermally stable NH3 -SCR catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 129, 3304–3308, 10.1002/ange.201610547.

- Ma, Y.; Han, S.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, L.; Luan, H.; Meng, X.; Xiao, F.-S.; One-pot fabrication of metal-zeolite catalysts from a combination of solvent-free and sodium-free routes. Catal. Today 2020, in press, in press, 10.1016/j.cattod.2020.06.037.

- Kwak, J.H.; Tonkyn, R.G.; Kim, D.H.; Szanyi, J.; Peden, C.H.; Excellent activity and selectivity of Cu-SSZ-13 in the selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3. J. Catal. 2010, 275, 187–190, 10.1016/j.jcat.2010.07.031.

- Wang, T.; Yang, C.; Li, S.; Yu, G.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Gao, P.; Sun, Y.; Solvent-free synthesis of Mg-incorporated nanocrystalline SAPO-34 zeolites via natural clay for chloromethane-to-olefin conversion. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 4185–4193, 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b07129.

- Liu, Z.; Nomura, N.; Nishioka, D.; Hotta, Y.; Matsuo, T.; Oshima, K.; Yanaba, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Ohara, K.; Kohara, S.; et al. A top-down methodology for ultrafast tuning of nanosized zeolites. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12567–12570, 10.1039/C5CC04542H.

- Přech, J.; Pizarro, P.; Serrano, D.; Čejka, J.; From 3D to 2D zeolite catalytic materials . Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 8263–8306, 10.1039/C8CS00370J.

- Zhang, K.; Ostraat, M.L.; Innovations in hierarchical zeolite synthesis. Catal. Today 2016, 264, 3–15, 10.1016/j.cattod.2015.08.012.

- Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Sun, Q.; Sheng, N.; Liu, Y.; Bian, C.; Chen, F.; Meng, X.; Xiao, F.S.; Solvent-free syntheses of hierarchically porous aluminophosphate-based zeolites with AEL and AFI structures. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 17616–17623, 10.1002/chem.201403890.

- Sheng, N.; Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Chu, Y.; Han, S.; Meng, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Xiao, F.-S.; Self-formation of hierarchical SAPO-11 molecular sieves as an efficient hydroisomerization support. Catal. Today 2020, 350, 165–170, 10.1016/j.cattod.2019.06.069.

- Zeng, S.; Wang, R.; Li, A.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, S.; Solvent-free synthesis of nanosized hierarchical sodalite zeolite with a multi-hollow polycrystalline structure. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 6779–6783, 10.1039/C6CE01373B.

- Li, H.; Liu, X.; Qi, S.; Xu, L.; Shi, G.; Ding, Y.; Yan, X.; Huang, Y.; Geng, J.; Graphene oxide facilitates solvent-free synthesis of well-dispersed, faceted zeolite crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 14090–14095, 10.1002/anie.201707823.

- Maghfirah, A.; Ilmi, M.M.; Fajar, A.T.N.; Kadja, G.T.M.; A review on the green synthesis of hierarchically porous zeolite. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, , 17, 100348, 10.1016/j.mtchem.2020.100348.

- Nichterwitz, M.; Grätz, S.; Nickel, W.; Borchardt, L.; Solvent-free hierarchization of zeolites by carbochlorination. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 221-229, 10.1039/C6TA09145H.

- Liu, Z.; Ren, S.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, G.; Wu, X.; Yu, G.; Qiu, M.; Yang, C.; Sun, Y.; et al. Melting-assisted solvent-free synthesis of hierarchical SAPO-34 with enhanced methanol to olefins (MTO) performance. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 423–427, 10.1039/C7CY02283B.

- Yu, G.; Chen, X.; Xue, W.; Ge, L.; Wang, T.; Qiu, M.; Wei, W.; Gao, P.; Sun, Y.; Melting-assisted solvent-free synthesis of SAPO-11 for improving the hydroisomerization performance of n-dodecane. Chin. J. Catal. 2020, 41, 622–630, 10.1016/S1872-2067(19)63466-2.

- Seo, Y.; Lee, S.; Jo, C.; Ryoo, R.; Microporous aluminophosphate nanosheets and their nanomorphic zeolite analogues tailored by hierarchical structure-directing amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8806–8809, 10.1021/ja403580j.

- Kodaira, T.; Nabata, A.; Ikeda, T.; A new aluminophosphate phase, AlPO-NS, with a bellows-like morphology obtained from prolonged hydrothermal process or increased pH value of initial solution for synthesizing AlPO4-5. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 162, 31–35, 10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.06.003.

- Wu, L.; Liu, Z.; Xia, L.; Qiu, M.; Liu, X.; Zhu, H.; Sun, Y.; Effect of SAPO-34 molecular sieve morphology on methanol to olefins performance. Chin. J. Catal. 2013, 34, 1348–1356, 10.1016/S1872-2067(12)60575-0.

- Wu, D.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; Yu, G.; Zhang, K.; Qiu, M.; Xue, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; et al. Morphology-controlled synthesis of H-type MFI zeolites with unique stacked structures through a one-pot solvent-free Strategy. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 3871–3877, 10.1002/cssc.201900663.

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Dong, M.; Fan, S.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J.; Fan, W.; Strategies to control zeolite particle morphology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 885–907, 10.1039/C8CS00774H.

- Zhang, J.; Lu, X.; Wang, Z.; Control of crystallization rate and morphology of zeolite silicalite-1 in solvent-free synthesis.. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 283, 14–24, 10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.03.044.

- Chen, X.; Meng, X.; Xiao, F.-S.; Solvent-free synthesis of SAPO-5 zeolite with plate-like morphology in the presence of surfactants. Chin. J. Catal. 2015, 36, 797–800, 10.1016/S1872-2067(14)60285-0.

- Yu, X.; Zhou, C.; Chen, X.; Gao, P.; Qiu, M.; Xue, W.; Yang, C.; Zhao, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; et al.et al. Facile solvent-free synthesis of hollow fiber catalyst assembled by c-axis oriented ZSM-5 crystals. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 5619–5626, 10.1002/cctc.201801517.

- Liu, Z.; Wu, D.; Ren, S.; Chen, X.; Qiu, M.; Wu, X.; Yang, C.; Zeng, G.; Sun, Y.; Solvent-free synthesis of c-axis oriented ZSM-5 crystals with enhanced methanol to gasoline catalytic activity. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 3317–3322, 10.1002/cctc.201600896.

- Li, D.; Qiu, L.; Wang, K.; Zeng, Y.; Williams, T.; Huang, Y.; Tsapatsis, M.; Wang, H.; Growth of zeolite crystals with graphene oxide nanosheets. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2249–2251, 10.1039/c2cc17378f.

- Chen, L.-H.; Li, X.-Y.; Rooke, J.C.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Yang, X.-Y.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, F.-S.; Su, B.-L.; Hierarchically structured zeolites: Synthesis, mass transport properties and applications. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 17381–17403, 10.1039/c2jm31957h.

- Morris, R.E.; James, S.L.; Solventless synthesis of zeolites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2163–2165, 10.1002/anie.201209002.

- Xiao, Y.; Sheng, N.; Chu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, X.; Deng, F.; Meng, X.; Feng, Z.; Mechanism on solvent-free crystallization of NaA zeolite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 237, 201–209, 10.1016/j.micromeso.2016.09.029.

- Wang, X.; Wu, Q.; Chen, C.; Pan, S.; Zhang, W.; Meng, X.; Maurer, S.; Feyen, M.; Muller, U.; Xiao, F.S.; et al. Atom-economical synthesis of a high silica CHA zeolite using a solvent-free route. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 16920–16923, 10.1039/C5CC05980A.

- Liu, Z.; Wu, D.; Ren, S.; Chen, X.; Qiu, M.; Liu, G.; Zeng, G.; Sun, Y.; Facile one-pot solvent-free synthesis of hierarchical ZSM-5 for methanol to gasoline conversion. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 15816–15820, 10.1039/C6RA00247A.

- Zhang, C.; Wu, Q.; Lei, C.; Pan, S.; Bian, C.; Wang, L.; Meng, X.; Xiao, F.-S.; Solvent-free and mesoporogen-free synthesis of mesoporous aluminosilicate ZSM-5 zeolites with superior catalytic properties in the methanol-to-olefins reaction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 1450–1460, 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b00062.

- Nada, M.H.; Larsen, S.C.; Gillan, E.G.; Solvent-free synthesis of crystalline ZSM-5 zeolite: Investigation of mechanochemical pre-reaction impact on growth of thermally stable zeolite structures. Solid State Sci. 2019, 94, 15–22, 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2019.05.009.

- Zhang, B.; Douthwaite, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Q.; Shi, R.; Wu, P.; Liu, K.; Wang, Z.; Lin, W.; et al. Seed-and solvent-free synthesis of ZSM-5 with tuneable Si/Al ratios for biomass hydrogenation. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 1630–1638, 10.1039/C9GC03622A.

- Bian, C.; Zhang, C.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Zhang, W.; Meng, X.; Maurer, S.; Dai, D.; Parvulescu, A.-N.; Müller, U.; et al. Generalized high-temperature synthesis of zeolite catalysts with unpredictably high space-time yields (STYs). J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 2613–2618, 10.1039/C6TA09866E.

- Kornas, A.; Olszówka, J.E.; Urbanova, M.; Mlekodaj, K.; Brabec, L.; Rathousky, J.; Dedecek, J.; Pashkova, V.; Milling activation for the solvent-free synthesis of the zeolite mordenite. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 2791–2797, 10.1002/ejic.202000320.

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, Q.; Bian, C.; Pan, S.; Meng, X.; Xiao, F.-S.; Solvent-free synthesis of titanosilicate zeolites. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 14093–14095, 10.1039/C5TA02680F.

- Zhai, H.; Bian, C.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Guo, L.; Wang, X.; Yu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Cao, X.; Sustainable route for synthesis of all-silica SOD zeolite. Crystals 2019, 9, 338, 10.3390/cryst9070338.

- Liu, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xu, L.; Mintova, S.; Yan, Z.; Liu, X.; Silicoaluminophosphate-11 (SAPO-11) molecular sieves synthesized via a grinding synthesis method. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 10950–10953, 10.1039/C8CC05952G.

- Shan, Y.; Shi, X.; Du, J.; Yan, Z.; Yu, Y.; He, H.; SSZ-13 synthesized by solvent-free method: A potential candidate for NH3-SCR catalyst with high activity and hydrothermal stability. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 5397–5403, 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b05822.

- Wu, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Meng, X.; Deng, F.; Fan, F.; Feng, Z.; Li, C.; Maurer, S.; Feyen, M.; et al. Solvent-free synthesis of ITQ-12, ITQ-13, and ITQ-17 zeolites. Chin. J. Chem. 2017, 35, 572–576, 10.1002/cjoc.201600646.

- Cheng, S.; Zhang, G.; Javed, M.; Gao, W.; Mazonde, B.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, C.; Yang, R.; Xing, C.; Solvent-free synthesis of 1D cancrinite zeolite for unexpectedly improved gasoline selectivity. Chemistryselect 2018, 3, 2115–2119, 10.1002/slct.201703056.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Meng, X.; Han, S.; Zhu, Q.; Sheng, N.; Wang, L.; Xiao, F.-S.; Sustainable and efficient synthesis of nanosized EMT zeolites under solvent-free and organotemplate-free conditions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 286, 105–109, 10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.05.037.

- Xu, H.; Zhu, J.; Qiao, J.; Yu, X.; Sun, N.-B.; Bian, C.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Solvent-free synthesis of aluminosilicate SSZ-39 zeolite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 312, 110736, 10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110736.