Immunotherapy, including chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, cancer vaccines, and dendritic cell therapy, has been incorporated as a fifth modality of modern cancer care, along with surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and target therapy. Among them, CAR T-cell therapy emerges as one of the most promising treatments. In 2017, the first two CAR T-cell drugs, tisagenlecleucel and axicabtagene ciloleucel for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), respectively, were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In addition to the successful applications to hematologi-cal malignancies, CAR T-cell therapy has been investigated to potentially treat solid tumors, in-cluding pediatric brain tumor, which serves as the leading cause of cancer-associated death for children and adolescents.

- chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells

- gene modified-based cellular platform

- immunothera-py

- pediatric brain tumor

1. Introduction of Pediatric Brain Tumors

Primary malignant central nervous system (CNS) tumors, including medulloblastomas, ependymomas, astrocytomas, and germ cell tumors, serve as the second most common pediatric malignancies, just after hematological cancers [1]. Nevertheless, they last as a main reason of pediatric cancer-related death [2]. Among them, more than 90% are located in the brain, with an incidence of 1.12–5.14 cases per 100,000 children [3]. While the etiology of childhood brain tumors remains unclear, it has been proposed that genetic factors, environmental factors, family history, parental age at birth and cancer predisposition syndromes might be related [4].

Currently, surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy are the major therapeutic strategies for pediatric brain tumors [5]. Even though chemotherapy and radiotherapy are more effective in pediatric patients with brain tumors than their adult counterparts [6], significant neurologic deficits and neurocognitive morbidities which impede future ability to live independently are concern [7]. Under these circumstances, immunotherapy, which only selectively destroys malignant cells expressing target antigen while leaving healthy tissues undamaged, may be a valuable therapeutic option. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, in particular, targeting tumor-specific antigens via genetically modified T cells, might be more useful for pediatric brain tumors, as they are well-known for the lack of high somatic tumor mutational burden [8][9].

2. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-Cell Therapy

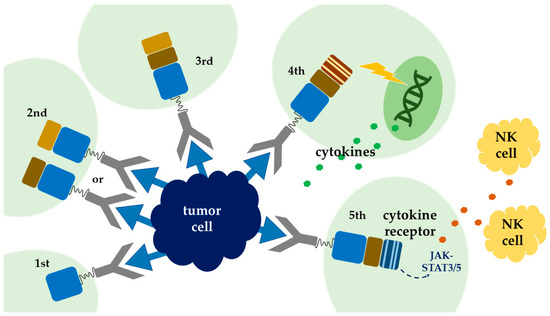

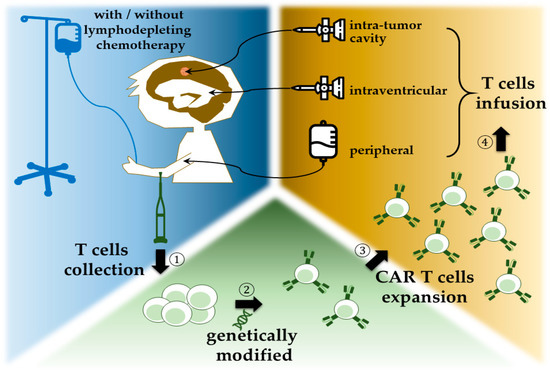

CARs are artificially synthesized proteins which incorporate three major components: an extracellular tumor-specific antibody, an intracellular signaling motif, and a transmembrane domain serving as a bridge

. The outermost part is responsible for antigen targeting, as it possesses a single-chain fragment (scFv) purified from antibody that is specific for tumor antigens

. This part of CARs is responsible for being bound to tumor cells and triggering consequent T-cell activation and proliferation, and inaugurates cytokine release and cytolytic degranulation

. As for intracellular domain, it determines the strength, quality, and persistence of a T-cell response to tumor antigens

, and it is frequently manipulated to enhance the potency of CAR T-cell therapy. To date, there are five generations of CARs being developed. The endodomain of the first generation of CARs comprises the CD3-ζ chain alone, with limited T-cell expansion and insufficient cytokine release

. Under this consideration, the second generation of CARs incorporated costimulatory domain, either CD28

or 4-1BB

, intracellularly, to ameliorate T-cell proliferation and persistence

. The third generation combined CD28 and 4-1BB

, to further increase T-cell expression and persistence. Meanwhile there are two main immune systems, namely innate immune and adaptive immune in human body. Innate immune system, which serves as the first line of immune response and is antigen-independent, is thought to be helpful in adaptive T-cell therapy. Thus, another modulation combining innate immune response with CAR T cells was proposed. The recent fourth generation added cytokines, such as interleukin-12 (IL-12), to the endodomain of the second generation; they which could activate T cells, as well as natural killer cells, simultaneously, when encountering tumor cells

. A natural killer cell is capable of appealing cytokine cassette and inducing cytotoxicity against tumor cells

. This combination allows antigen-negative cancer cells to be eliminated concurrently. This mergence was termed T cell redirected for universal cytokine-mediated killing (TRUCKs)

. In this situation, tumor microenvironments are amended, and the lifespan of CAR T cells is prolonged. The clinical trials of this concept combining innate and adaptive immunity are still in cradle

. By synchronous installation of IL-2 receptor and binding site for the transcription factor STAT3 to the endodomain, vigorous JAK–STAT3/5 cytokine, cascade can be instigated in local tumor environment and thus minimizes systemic inflammation

(

). The contemporary protocol of CAR T-cell therapy adopted autologous T cells (

).

3. Application of CAR T-Cell Therapy, from Hematological Malignancies to Pediatric Brain Tumors

In 2012, the first child received CD19-targeted CAR-T therapy for her relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia exhibited complete remission and no refractory or relapse for more than five years [26]. This finding opened up a new era of CAR-T therapy for malignancies. Afterwards, several studies demonstrated promising response, ranging from 60% to 93% complete remission rate, with minimal residual disease (MRD)-negative of CAR-T therapy for pediatric hematological malignancies [27][28][29][30]. The first CAR-T therapy, tisagenlecleucel, was approved by the FDA in August 2017 for refractory or relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia in patients younger than 25 years old [31][32][33]. In October of the same year, axicabtagene ciloleucel was approved for refractory or relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as well [34]. These striking successes may be due to specific homogeneous tumor target antigens in B-cell lineages [35]. With the encouraging results in hematological malignancies, CAR-T therapy was used to treat a variety of solid tumors. However, the response to solid tumors was not as effective as that of hematological malignancies [36]. The possible reasons include heterogeneous and low specific target antigen expression on tumor surface, insufficient CAR T cells traveling to and infiltrating into the tumor, limited T-cell expansion, and poor persistence because of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment [35][37]. Brain tumors are notorious for their immunosuppression environment, possibly due to the unique composition of the extracellular matrix; distinctive tissue-resident cell types, such as astrocytes, which are known to blunt cytotoxicity; and a natural inflammation shelter/blood–brain barrier (BBB) [38]. Furthermore, possible on-target off-tumor toxicity of CAR-T therapy may reduce the cytotoxic effect on tumor cells and may increase potential treatment-related toxicities on normal tissues [39]. Nevertheless, several clinical and preclinical studies have shown favorable efficacy in solid tumors, especially anti-carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) therapy, including CD3ζ, CD28–CD3ζ, and locally administered CAR T cells [40].

Zhang et al. demonstrated that 7 of 10 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard treatments became stable disease (SD) from progressive disease (PD) after undergoing treatment with CAR T cells [41]. Thistlethwaite and her colleagues also reported that 7 of 14 relapsed and refractory metastatic gastrointestinal patients achieved stable disease and persisted for six weeks after CAR T-cells infusion. One of the patients even stayed alive for 56 months [42]. In other kinds of malignancies, such as high-risk osteosarcoma, Chulanetra et al. proved that CAR T cells have synergistic effect with doxorubicin on eliminating tumor cells of osteosarcoma [43]. Some patients developed transient side effects such as acute respiratory toxicity, but no severe irreversible toxicity was observed in patients underwent treatment [44]. The outcomes of these abovementioned trials support the efficacy and safety of the CAR-T therapy. Therefore, more and more clinical trials aim to achieve the promising results of application in pediatric solid tumors, especially brain tumors [45][46][47][48]. Though medical technology has improved largely in the past few decades, treatments for brain tumors are still disappointing [49][50]. Highly specific and personalized treatments such as CAR T-cell therapy offer an opportunity to fight against pediatric brain tumors [51].

References

- Bhakta, N.; Force, L.M.; Allemani, C.; Atun, R.; Bray, F.; Coleman, M.P.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Frazier, A.L.; Robison, L.L.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; et al. Childhood cancer burden: A review of global estimates. Lancet. Oncol. 2019, 20, e42–e53.

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30.

- Subramanian, S.; Ahmad, T. Cancer, Childhood Brain Tumors; StatPearls Publishing: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2019.

- Reilly, K.M. Brain tumor susceptibility: The role of genetic factors and uses of mouse models to unravel risk. Brain Pathol. 2009, 19, 121–131.

- Udaka, Y.T.; Packer, R.J. Pediatric brain tumors. Neurol. Clin. 2018, 36, 533–556.

- Merchant, T.E.; Pollack, I.F.; Loeffler, J.S. Brain Tumors Across the Age Spectrum: Biology, Therapy, and Late Effects. In Seminars in Radiation Oncology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 58–66.

- Wang, S.S.; Bandopadhayay, P.; Jenkins, M.R. Towards immunotherapy for pediatric brain tumors. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 748–761.

- Grigor, E.J.M.; Fergusson, D.; Kekre, N.; Montroy, J.; Atkins, H.; Seftel, M.D.; Daugaard, M.; Presseau, J.; Thavorn, K.; Hutton, B.; et al. Risks and benefits of chimeric antigen receptor t-cell (car-t) therapy in cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2019, 33, 98–110.

- June, C.H.; Sadelain, M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 64–73.

- Sadelain, M.; Brentjens, R.; Rivière, I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 388–398.

- Srivastava, S.; Riddell, S.R. Engineering car-t cells: Design concepts. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 494–502.

- Sadelain, M.; Rivière, I.; Brentjens, R. Targeting tumours with genetically enhanced t lymphocytes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 35–45.

- Hombach, A.; Wieczarkowiecz, A.; Marquardt, T.; Heuser, C.; Usai, L.; Pohl, C.; Seliger, B.; Abken, H. Tumor-specific t cell activation by recombinant immunoreceptors: Cd3 zeta signaling and cd28 costimulation are simultaneously required for efficient il-2 secretion and can be integrated into one combined cd28/cd3 zeta signaling receptor molecule. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 6123–6131.

- Lafferty, K.J.; Cunningham, A.J. A new analysis of allogeneic interactions. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 1975, 53, 27–42.

- Firor, A.E.; Jares, A.; Ma, Y. From humble beginnings to success in the clinic: Chimeric antigen receptor-modified t-cells and implications for immunotherapy. Exp. Biol. Med. 2015, 240, 1087–1098.

- Finney, H.M.; Lawson, A.D.; Bebbington, C.R.; Weir, A.N. Chimeric receptors providing both primary and costimulatory signaling in t cells from a single gene product. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 2791–2797.

- Brentjens, R.J.; Santos, E.; Nikhamin, Y.; Yeh, R.; Matsushita, M.; La Perle, K.; Quintás-Cardama, A.; Larson, S.M.; Sadelain, M. Genetically targeted t cells eradicate systemic acute lymphoblastic leukemia xenografts. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 5426–5435.

- Imai, C.; Mihara, K.; Andreansky, M.; Nicholson, I.C.; Pui, C.H.; Geiger, T.L.; Campana, D. Chimeric receptors with 4–1bb signaling capacity provoke potent cytotoxicity against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2004, 18, 676–684.

- Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhong, J.F.; Zhang, X. Engineering car-t cells. Biomark Res. 2017, 5, 22.

- Morgan, R.A.; Yang, J.C.; Kitano, M.; Dudley, M.E.; Laurencot, C.M.; Rosenberg, S.A. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of t cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 843–851.

- Heczey, A.; Louis, C.U.; Savoldo, B.; Dakhova, O.; Durett, A.; Grilley, B.; Liu, H.; Wu, M.F.; Mei, Z.; Gee, A.; et al. Car t cells administered in combination with lymphodepletion and pd-1 inhibition to patients with neuroblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 2214–2224.

- Chmielewski, M.; Abken, H. Trucks: The fourth generation of cars. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2015, 15, 1145–1154.

- Vivier, E.; Tomasello, E.; Baratin, M.; Walzer, T.; Ugolini, S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 503–510.

- Chmielewski, M.; Abken, H. Trucks, the fourth-generation car t cells: Current developments and clinical translation. Adv. Cell Gene Ther. 2020, 3, e84.

- Tokarew, N.; Ogonek, J.; Endres, S.; von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.; Kobold, S. Teaching an old dog new tricks: Next-generation car t cells. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 26–37.

- Rosenbaum, L. Tragedy, perseverance, and chance—the story of car-t therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 10–56.

- Gardner, R.A.; Finney, O.; Annesley, C.; Brakke, H.; Summers, C.; Leger, K.; Bleakley, M.; Brown, C.; Mgebroff, S.; Kelly-Spratt, K.S.; et al. Intent-to-treat leukemia remission by cd19 car t cells of defined formulation and dose in children and young adults. Blood 2017, 129, 3322–3331.

- Ghorashian, S.; Pule, M.; Amrolia, P. Cd 19 chimeric antigen receptor t cell therapy for haematological malignancies. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 169, 463–478.

- Lee, D.W.; Kochenderfer, J.N.; Stetler-Stevenson, M.; Cui, Y.K.; Delbrook, C.; Feldman, S.A.; Fry, T.J.; Orentas, R.; Sabatino, M.; Shah, N.N.; et al. T cells expressing cd19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: A phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 517–528.

- Maude, S.L.; Frey, N.; Shaw, P.A.; Aplenc, R.; Barrett, D.M.; Bunin, N.J.; Chew, A.; Gonzalez, V.E.; Zheng, Z.; Lacey, S.F.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor t cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1507–1517.

- Ahmad, A.; Uddin, S.; Steinhoff, M. Car-t cell therapies: An overview of clinical studies supporting their approved use against acute lymphoblastic leukemia and large b-cell lymphomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3906.

- Maude, S.L.; Laetsch, T.W.; Buechner, J.; Rives, S.; Boyer, M.; Bittencourt, H.; Bader, P.; Verneris, M.R.; Stefanski, H.E.; Myers, G.D.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with b-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 439–448.

- O’Leary, M.C.; Lu, X.; Huang, Y.; Lin, X.; Mahmood, I.; Przepiorka, D.; Gavin, D.; Lee, S.; Liu, K.; George, B. Fda approval summary: Tisagenlecleucel for treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory b-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 1142–1146.

- Bouchkouj, N.; Kasamon, Y.L.; de Claro, R.A.; George, B.; Lin, X.; Lee, S.; Blumenthal, G.M.; Bryan, W.; McKee, A.E.; Pazdur, R. Fda approval summary: Axicabtagene ciloleucel for relapsed or refractory large b-cell lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 1702–1708.

- Akhavan, D.; Alizadeh, D.; Wang, D.; Weist, M.R.; Shepphird, J.K.; Brown, C.E. Car t cells for brain tumors: Lessons learned and road ahead. Immunol. Rev. 2019, 290, 60–84.

- Dai, H.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X.; Han, W. Chimeric antigen receptors modified t-cells for cancer therapy. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108.

- Tormoen, G.W.; Crittenden, M.R.; Gough, M.J. Role of the immunosuppressive microenvironment in immunotherapy. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 3, 520–526.

- Quail, D.F.; Joyce, J.A. The microenvironmental landscape of brain tumors. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 326–341.

- Sun, S.; Hao, H.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y. Immunotherapy with car-modified t cells: Toxicities and overcoming strategies. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018.

- Holzinger, A.; Abken, H. Car t cells targeting solid tumors: Carcinoembryonic antigen (cea) proves to be a safe target. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2017, 66, 1505–1507.

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wang, M.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xiong, Z.; Wei, Z.; Shen, J.; et al. Phase i escalating-dose trial of car-t therapy targeting cea + metastatic colorectal cancers. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 1248–1258.

- Thistlethwaite, F.C.; Gilham, D.E.; Guest, R.D.; Rothwell, D.G.; Pillai, M.; Burt, D.J.; Byatte, A.J.; Kirillova, N.; Valle, J.W.; Sharma, S.K.; et al. The clinical efficacy of first-generation carcinoembryonic antigen (ceacam5)-specific car t cells is limited by poor persistence and transient pre-conditioning-dependent respiratory toxicity. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2017, 66, 1425–1436.

- Chulanetra, M.; Morchang, A.; Sayour, E.; Eldjerou, L.; Milner, R.; Lagmay, J.; Cascio, M.; Stover, B.; Slayton, W.; Chaicumpa, W.; et al. Gd2 chimeric antigen receptor modified t cells in synergy with sub-toxic level of doxorubicin targeting osteosarcomas. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 674.

- Katz, S.C.; Burga, R.A.; McCormack, E.; Wang, L.J.; Mooring, W.; Point, G.R.; Khare, P.D.; Thorn, M.; Ma, Q.; Stainken, B.F.; et al. Phase i hepatic immunotherapy for metastases study of intra-arterial chimeric antigen receptor–modified t-cell therapy for cea + liver metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 3149–3159.

- Ahmed, N.; Brawley, V.; Hegde, M.; Bielamowicz, K.; Kalra, M.; Landi, D.; Robertson, C.; Gray, T.L.; Diouf, O.; Wakefield, A.; et al. Her2-specific chimeric antigen receptor—modified virus-specific t cells for progressive glioblastoma: A phase 1 dose-escalation trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1094–1101.

- Brown, C.E.; Badie, B.; Barish, M.E.; Weng, L.; Ostberg, J.R.; Chang, W.-C.; Naranjo, A.; Starr, R.; Wagner, J.; Wright, C.; et al. Bioactivity and safety of il13rα2-redirected chimeric antigen receptor cd8 + t cells in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4062–4072.

- Goff, S.L.; Morgan, R.A.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Robbins, P.F.; Restifo, N.P.; Feldman, S.A.; Lu, Y.-C.; Lu, L.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Pilot trial of adoptive transfer of chimeric antigen receptor transduced t cells targeting egfrviii in patients with glioblastoma. J. Immunother. 2019, 42, 126.

- O’Rourke, D.M.; Nasrallah, M.P.; Desai, A.; Melenhorst, J.J.; Mansfield, K.; Morrissette, J.J.; Martinez-Lage, M.; Brem, S.; Maloney, E.; Shen, A.; et al. A single dose of peripherally infused egfrviii-directed car t cells mediates antigen loss and induces adaptive resistance in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9.

- Davis, M.E. Glioblastoma: Overview of disease and treatment. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 20, S2–S8.

- DeNunzio, N.J.; Yock, T.I. Modern radiotherapy for pediatric brain tumors. Cancers 2020, 12, 1533.

- Feins, S.; Kong, W.; Williams, E.F.; Milone, M.C.; Fraietta, J.A. An introduction to chimeric antigen receptor (car) t-cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, S3–S9.