RNAs with methylated cap structures are present throughout multiple domains of life. Given that cap structures play a myriad of important roles beyond translation, such as stability and immune recognition, it is not surprising that viruses have adopted RNA capping processes for their own benefit throughout co-evolution with their hosts. In fact, that RNAs are capped was first discovered in a member of the Spinareovirinae family, Cypovirus, before these findings were translated to other domains of life.

- Spinareovirinae

- reovirus

- capping

- RNA

- Orthoreovirus

- Aquareovirus

- Cypovirus

- transcription

- nucleotide

- virus

1. Introduction

Although this review centers on RNA capping by members of the Spinareovirinae subfamily, we will first provide a brief introduction to the virus family phylogeny, basic structure, and replication cycle.

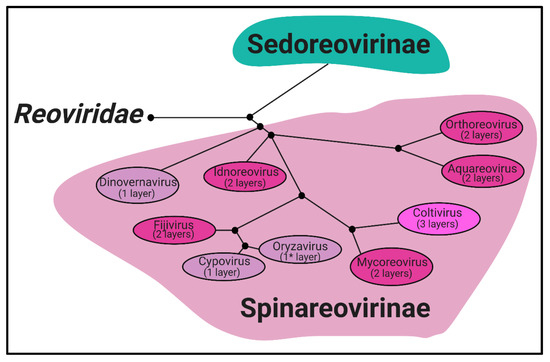

Phylogeny. Reoviridae is a family of segmented, dsRNA viruses divided into two subfamilies based on the presence of “turrets/spikes” at the vertices of the viral capsid [1]. The non-turreted members of the Reoviridae family form the Sedoreovirinae subfamily, while the turreted viruses form the Spinareovirinae subfamily, the focus of this review. The Spinareovirinae subfamily is composed of nine genera: Orthoreovirus, Aquareovirus, Coltivirus, Mycoreovirus, Cypovirus, Fijivirus, Dinovernavirus, Idnoreovirus, and Oryzavirus, with a wide host range including vertebrates, invertebrates, plants, and fungi. Phylogenetic trees based on the amino acid (aa) sequences of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps) have been built to visualize the relationship between each virus, as depicted in Figure 1. Though structurally conserved, when comparing aa sequences of homologous proteins among the genera, there is often less than 26% sequence similarity. However, protein regions with structural and/or enzymatic function are typically more similar than the rest of the protein [1].

phylogenetic tree. A phylogenetic tree (neighbour joining) of the

subfamily,

. Clustering is determined by sequence homology between the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase protein sequences. Capsid layers found among each genus are indicated. *

contains a complete core particle, and a partial outercapsid more closely resembling intermediate subviral particles (ISVPs) seen with

(MRV),

. Figure generated using BLOSUM62 and re-illustrated using Biorender.com. Accession numbers: (AKG65873, ALK02203 for

), (AGR34045, AAM92745, AAL31497 for

), (AAM18342, 690891, AAK00595 for

), (001936004, BAC98431 for

), (AEC32904, AAC36456 for

), (AAN46860, AAK73087 for

), (Q8JYK1, BAA08542 for

), (ABB17205 for

) and (AAZ94068 for

).

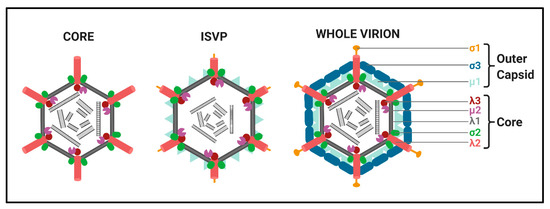

Structures of

: Transcriptionally active MRV cores composed of the λ1 shell (grey) held together by the σ2 clamps (green). The λ2 turrets (red) are found at each vertex, below which the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) λ3 (maroon) and μ2 (purple) are predicted to sit;

: Intermediate subviral particles (ISVPs) are generated through proteolytical cleavage within endosomes after cell-entry. The σ3 outercapsid protein is completely cleaved away, while μ1 (light blue) is cleaved to δ. The σ1 attachment protein (yellow) is also cleaved at the N-terminus. ISVPs may also be generated in the natural niche, which for MRV is the intestinal tract;

: Transcriptionally inactive whole virions are generated from core particles becoming decorated with σ3 (dark blue) and μ1 heterohexamers, forming the outercapsid. Additionally, complete σ1 proteins also attach to the λ2 pentamers. Figure generated using Biorender.com.

Structure. All Spinareovirinae members share the same, basic virion structure: concentric layers of proteins with icosahedral symmetry encapsidating the segmented dsRNA genomes (Figure 2) [1]. The number of layers varies among the genera, as depicted in Figure 1. All Spinareovirinae members consist of a core, or innermost particle, which is transcriptionally active with T = 1 symmetry. The core particle is formed by 60 asymmetric homodimers of the major-core structural protein, λ1 of Mammalian Orthoreovirus (MRV, or “reovirus” henceforth) [2,3][2][3]. All proteins discussed hereafter will be given the MRV designation; however, it is important to recognize that homologous proteins of the other genera may have different names. Enforcing this backbone structure are the “clamp” σ2 proteins, which are only present among Spinareovirinae [2,4][2][4]. MRV contains 150 copies of the clamp protein, distributed about the 5-, 3-, and 2-fold axes [2]. At the twelve 5-fold axes sits the pentameric “turrets”, formed by the λ2 protein [2,5][2][5]. These turrets form hollow cylinders and possess both methyl- and guanylyl-transferase activity (MTase and GTase, respectively), discussed in detail in later sections. Among all the genera, there are always 12 turrets; however, their shapes and configurations vary. For example, Oryzavirus has both wider and taller turrets compared to MRV [4]. The shape of the λ2 turrets may reflect differences in infection and transcriptional mechanisms; when the outercapsid of MRV is cleaved away, the λ2 turrets take on a more “open” conformation, potentially facilitating the release of mRNA into the host cytoplasm [6].

Some Spinareovirinae members, such as Oryzavirus, Cypovirus, and Dinovernavirus, do not have additional layers beyond the core particle. In contrast, Orthoreovirus, Aquareovirus, Coltivirus, Mycoreovirus, Fijivirus, and Idnoreovirus have layers of outercapsid proteins with considerable structural similarity that surround the innermost core particle, forming a T = 13 symmetrical structure. (Figure 2) [1]. Two major outercapsid proteins, μ1 and σ3, form heterohexamers (200 units for MRV) that attach onto the core particles, forming the T = 13 lattice [3,7][3][7]. The μ1 proteins found within these complexes contact both the σ2 clamps and λ2 turrets to anchor the outercapsid onto the core [2,3][2][3]. In the case of MRV, there is an additional outercapsid receptor binding protein that is absent among the other Spinareovirinae genera, σ1, known to bind both junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A) and sialic acids (SAs) on the surface of mammalian cells [1,8][1][8].

Members of the Spinareovirinae subfamily have genomes consisting of 9–12 dsRNA segments, depending on the genera [1]. Most of these dsRNA segments encode a single viral protein, thus they are largely monocistronic. Spinareovirinaes’ genome segments share conserved sequences at their termini with 3′ terminal regions (UCAUC-3′ for MRV) typically more conserved than the 5′ sequences [1]. This may suggest functions for the non-coding regions of reovirus genomes, potentially in the regulation of transcription or encapsidation. As will be discussed in detail throughout this review, the (+)-sense RNAs of Spinareovirinae are capped. Unlike eukaryotic mRNAs, both genomic and transcribed Spinareovirinaes RNAs lack 3′-polyA tails.

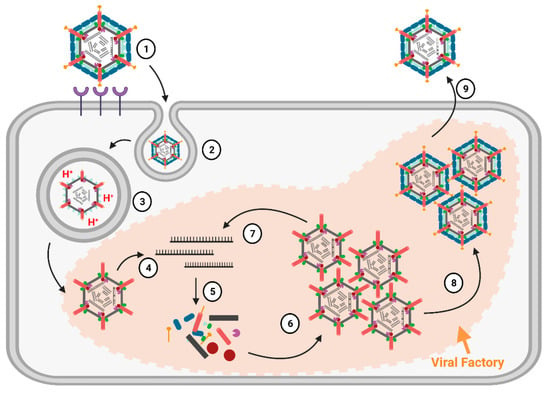

Replication Cycle. We will provide a brief overview of the replication cycle for MRV here, as illustrated in Figure 3; however, readers are directed to a recently published review [9] for a more in-depth description. Infection begins with entry of the virus into host cells, a process mediated by the attachment of the σ1 receptor binding protein to sialic acids (SAs) and/or junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A) residues [10]. In cell culture, MRVs are generally internalized by clathrin-mediated endocytosis, but can also internalize by phagocytosis or pinocytosis [11]. Within endosomes, acid-dependent proteolytic processing allows stepwise degradation of the outercapsid, beginning with σ3 degradation followed by μ1C cleavage, generating intermediate subviral particles (ISVPs) (Figure 2) [12]. Eventually, transcriptionally active core particles penetrate into the cytoplasm of the cell [12]. Given the natural niche for MRV is the intestine, it is believed that intestinal enzymes such as chymotrypsin kickstart the proteolytic degradation required for infection, generating ISVPs that can penetrate host membranes directly [13]. While MRV entry is well characterized, modes of entry for other Spinareovirinae members likely vary. For example, some Orthoreoviruses express a membrane fusion-inducing protein and can make use of syncytium formation for cell-to-cell spread [14].

Replication cycle of

. (1) Receptor-mediated attachment of complete virions via σ1 to junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A) and/or sialic acid (SA) residues on the mammalian cell surface; (2) Following membrane attachment, virions enter the cell via clathrin-mediated endocytosis; (3) Endosomal acid-dependent proteases digest the MRV outercapsid, generating ISVPs before the eventual release of core particles into the cytoplasm; (4) Now-transcriptionally active core particles produce mRNAs (initial replication) using the viral λ3 polymerase; (5) After being secreted through the λ2 channels, mRNAs are translated into proteins. Viral factories are formed which serve as sites for viral replication, and (6) assemble into more core particles; (7) These newly generated cores then transcribe more mRNA, which in turn is translated into more proteins and assembles into more cores; (8) Outercapsid proteins assemble onto cores, halting transcription and producing progeny fully-infectious virions; (9) Mature infectious virions egress from the cell and disseminate. Figure generated using Biorender.com.

An important feature of Spinareovirinae is that RNA transcription occurs within the core particles, and full-length mRNAs are extruded from the λ2 pentameric turrets. As will be comprehensively discussed in this review, the RNAs can also be capped before extrusion to the cytoplasm. The (+)-sense RNAs serve as messenger RNAs for the expression of viral proteins by the host translation machinery. Moreover, as de novo viral capsid proteins are synthesized, (+)-sense RNAs can also be encapsidated into progeny cores. Within progeny cores, (-)-sense RNAs are transcribed, producing the dsRNA genome that serves to amplify (+)-sense RNA synthesis. Primary transcription refers to the first RNA molecules produced by the incoming core particles, while secondary transcription refers to RNA synthesis by newly assembled core particles (Figure 3). The replication of reovirus occurs within localized areas called factories, which are composed of both viral proteins (μ2, μNS, and σNS) and host materials (endoplasmic reticulum (ER) fragments, microtubules, and possibly more) [15]. Ultimately, whole progeny viruses are assembled that can egress from cells, predominantly in a non-lytic manner [9].

2. Capping Status of Viral RNAS

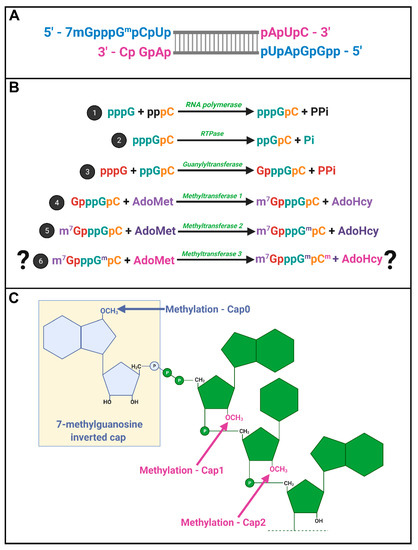

Spinareovirinae +RNAs have Cap1 structures. The years 1974–1976 were riveting for the topic of mRNA capping; Shatkin, Lengyel, and Kozak, along with their trainees and colleagues, discovered that mRNAs were capped and unravelled the enzymatic steps involved in cap addition and modification (Figure 4) [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27]. We recommend visiting these original publications to appreciate how this pivotal discovery was made and disseminated using radioisotopes such as 3H and 32P, enzymatic or chemical treatments, chromatography, brilliant experimental design, and a typewriter. Miura et al. (1974) first discovered that the 5′-terminal phosphates of MRV-synthesized RNAs were in a blocked configuration and could only be labelled by [32P] if the RNAs first underwent oxidation, beta-elimination, and phosphomonesterase treatment [28]. Upon removal of the blocking group, they found that the first nucleotide was always a modified guanine, thought probably to contain a 2′-O-methyl group, followed by a cytosine (GpCp). It is now well recognized that a 5′-GCUA sequence is indeed common to all ten MRV genome segments.

mRNA capping by

. (

) A depiction of the cap structures on 5′ termini of a dsRNA segment; (

) Proposed stepwise enzymatic generation of cap structures found within

RNA. An RdRp catalyzes the first step of the reaction, production of (+)RNA. Secondly, RTPase-mediated hydrolysis of the γ phosphate produces diphosphate RNA 5′ ends. In the third step, guanylyltransferase activity mediates the addition of guanosine via a reverse 5′ to 5′ triphosphate linkage. Methyltransferases then mediate methylation at the N7 position of the guanosine cap (step 4), and at the 2′O position of the adjacent first mRNA nucleotide (step 5), producing cap0 and cap1 structures sequentially. While it is debatable whether reovirus RNAs have additional methylation of the second RNA nucleotide to produce cap2 structures, such an activity would also require a methyltransferase; (

) Depictions of the molecular structures of RNA cap0, cap1, and cap2 with key methylated residues. Figure generated using Biorender.com.

Motivated by the finding that RNAs of several different viruses, including MRV, also contained methylated nucleotides [29[29][30][31][32],30,31,32], Shatkin’s group set out to define the precise composition of the 5′ termini. Through a series of differential enzymatic treatments and interpretation of chromatographic peaks, the Shatkin group showed that MRV cores synthesize mRNAs with a guanylate cap added to the 5′ end through a 5′-5′ inverted linkage (G(5′)ppp(5′)GpCp), rather than the conventional 5′-3′ linkage. The Shatkin lab also discovered that methyltransferase activities add a methyl group from S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) to the N7 position of the guanosine cap and the 2′O position of the adjacent first mRNA nucleotide (which is a guanine for MRV) to produce m7G(5′)ppp(5′)Gmp; a structure later termed “cap1”. It was already known that a viral-associated RNA triphosphatase (RTPase) could remove the γ-phosphate of nucleotides [33,34][33][34]; this hydrolase activity was now predicted to produce the diphosphate 5′guanine-cytosine terminus (5′ppGpCp) to which the inverted guanosine cap is added. One month following their description of the cap1 structure on in vitro synthesized RNAs, the Shatkin team demonstrated that the same cap1 structure was found on RNA genomes of viruses purified from infected cells; this suggested that cap1 structures are indeed produced during MRV infection and not just an artifact of in vitro systems [25]. By 1976, the cap1 structure was observed in numerous viruses and eukaryotes ranging from humans to silkworms to yeast; mRNAs being capped became an accepted dogma. The Spinareovirinae genomic dsRNA was then found to consist of capped (+)-sense RNAs, but diphosphate bearing (−)-sense RNAs that are uncapped and unmethylated at the 5′ end (Figure 4A).

In 1976, Furuichi et al. depicted the sequence of capping reactions along with the substrates and enzymatic activities involved [16,17,20][16][17][20]. Specifically, RTPase, guanylyltransferase (GTase), and two methyltransferases (MTases) are necessary, in that order, to generate the final cap1 structure on reovirus RNAs (Figure 4B). Later sections will discuss the possible location and orchestration of these enzymes in the context of Spinareovirinae.

Does reovirus also make cap2 structures? In 1976, Desrosiers et al. found that in L929 cells, 50% of MRV derived mRNAs also had a methyl group on the 2nd nucleotide not counting the guanosine cap; a structure referred to as cap2 (m7G5′ppp5′GmpCmp) (Figure 4C) [35]. The presence of cap2 structures on reovirus RNAs was also suggested by Shatkin and Both [19]. Specifically, while (+)-sense RNAs generated in vitro by reovirus cores had cap1, ~40% of (+)-sense RNAs synthesized during the infection of L929 cells at 5–11 h post infection (hpi) had cap2 structures. Moreover, cap2 was absent from the (+) strand of the dsRNA genome, suggesting that packaged (+)RNA was cap1-modified while ~40% of unpackaged (+)RNAs had cap2 structures [36]. Based on these findings, the authors proposed that cap1 versus cap2 structures may help regulate the fate of (+)RNAs, distinguishing protein translation versus packaging.

3. Functions of RNA Capping during Infection

Viral RNA transcription is not contingent on capping activity. As early as 1975 when the 5′cap structure was being discovered, there were speculations about its possible functions. Early studies demonstrated that capping was not essential for viral RNA transcription. Specifically, Reeve et al. [44][37] showed that the addition of [γ-S]GTP effectively prevented capping by resisting hydrolysis to the diphosphate (ppGpCp) substrate required for the capping reaction. Importantly, the addition of [γ-S]GTP did not interfere with viral RNA synthesis in vitro [44][37]. It would be interesting to perform similar studies in cell culture infections, not only to confirm that capping is dispensable for viral RNA synthesis, but as a strategy to explore the role of capping during reovirus replication. Noteworthy is that although [γ-S]GTP did not prevent RNA transcription, this does not indicate whether the RNA template within the virus particle had to be capped to serve as a template, as the addition of [γ-S]GTP does not affect the capping status of the input genomic template.

RNA capping promotes virus protein translation and RNA assembly. Unlike for viral RNA synthesis, the importance of mRNA capping for protein translation was well established by the 1980s. MRV mRNAs produced in the presence of methyl-donor SAM exhibited heightened ribosome binding and efficient translation in wheat germ or L929 cell lysate-based cell free translation systems [21,45][21][38]. These early studies inferred that 5′caps are involved in ribosome recruitment. Marilyn Kozak and Aaron Shatkin then demonstrated in 1976 that, indeed, the 43S ribosome initiation complex was recruited to the 5′terminus of mRNAs [18]. A higher proportion of 43S-protected fragments was obtained using methylated versus unmethylated mRNA, suggesting that m7G contributes to increased efficiency of 43S binding but is not absolutely required [45][38]. Furthermore, the 80S ribosomal complex was suggested to be formed at AUG-containing regions by recruitment of the 60S ribosomal subunit, since cap-containing RNAs without AUG start codons showed neither 43S nor 80S ribosome rebinding.

Given that mRNA capping promotes translation by recruiting the 43S ribosome complex to the initiation AUG site, the next logical question to ask would be: to what extent does the capping of reovirus mRNA enhance protein translation and assist in competition for host translation machinery? To begin addressing this question, our lab recently used the reovirus reverse genetics approach to compare de novo virus protein synthesis and progeny production in the presence versus absence of mRNA capping [46][39]. Specifically, transcription of all ten plasmid-derived MRV genome segments was driven by a T7 RNA polymerase promoter as is typical for the reverse genetics system, but the baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells were also variably transfected with the African Swine Fever Virus NP868R capping enzyme. In these experiments, it is important to point out that host capping enzymes are normally found in the nucleus where they remain inaccessible to reovirus particles present in the cytoplasm, thus the transfection of an exogenous capping enzyme allows mRNA produced in the cytoplasm to be capped. With that in mind, the inclusion of NP868R increased reovirus protein levels by ~10-fold, yet increased new progeny particle production by ~100-fold. These experiments suggested that mRNA capping serves additional functions beyond protein expression. To determine if capping promotes translation-independent steps of reovirus replication, BHK cells were infected with reovirus to produce capped viral RNAs, but also transfected concurrently with a plasmid-derived S1 genome segment modified to encode the green fluorescent protein, UnaG. Importantly, the experiments were conducted in the presence or absence of NP868R to produce capped or uncapped S1-UnaG mRNAs, respectively. In this experimental system, the virus infection produced all components for virus amplification and assembly, and the fate of capped or uncapped S1-UnaG alongside the infection could be monitored. Purified virions from the infected-transfected BHK cells were then added to Ras-transformed NIH3T3 cells, and the expression of UnaG from progeny virions was assessed by RT-qPCR and flow cytometry. S1-UnaG expression was only observed when progeny virions were produced in the presence of NP868R. These findings can be interpreted in two ways: (1) capping was essential for S1-UnaG mRNA to be encapsidated, or (2) both capped and uncapped S1-UnaG mRNAs were encapsidated but capping was essential for the subsequent transcription and expression of S1-UnaG transcripts. As discussed below, the reovirus polymerase has a cap-binding site that was previously suggested to serve as an anchor for the viral genomic RNA during transcription. Thus, a feasible possibility to explain the lack of infectious progeny with uncapped S1-UnaG is that the association of the polymerase with RNA caps is essential for RNA encapsidation, transcription, or both.

Aside from its roles in virus replication, the composition of the 5′ termini of RNAs can affect the host response to virus infection. It is now well established that viral RNAs are recognized as foreign by pattern recognition receptors such as toll-like receptors (TLR), RIG-I–like receptors (RIG-I), double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR), and melanoma differentiation–associated protein 5 (MDA5). The binding of viral RNA to these receptors results in type I IFN induction and downstream expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISG), many of which have antiviral properties. RIG-I was found to be the key pattern recognition receptor during MRV infection [47][40], as shRNA-mediated silencing of RIG-I prevented IFN production following reovirus infection. Additionally, while Ras-transformed cells with impaired RIG-I signaling permitted efficient reovirus dissemination, the silencing of RIG-I in non-transformed cells with functional RIG-I-signaling was necessary to allow efficient MRV cell-to-cell spread. In these studies, either MRV infection or transfection of in vitro synthesized m7G-capped but unmethylated reovirus (+)RNAs induced IFN-dependent antiviral effects. It would be interesting to repeat these studies with differentially modified reovirus (+)RNAs, cap1 or cap2 structures, to determine the role of methylation for RIG-I detection. Another study showed that 5′diphosphate-bearing reovirus -RNAs were also able to induce the IFN response in a RIG-I-dependent manner [48][41].

References

- Andrew, M.Q.; King, M.J.A.; Carstens, E.B.; Lefkowitz, E.J. Virus Taxonomy; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012.

- Reinisch, K.M.; Nibert, M.L.; Harrison, S.C. Structure of the reovirus core at 3.6?Å resolution. Nature 2000, 404, 960–967.

- Chandran, K.; Walker, S.B.; Chen, Y.A.; Contreras, C.M.; Schiff, L.A.; Baker, T.S.; Nibert, M.L. In Vitro Recoating of Reovirus Cores with Baculovirus-Expressed Outer-Capsid Proteins 1 and 3. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 3941–3950.

- Miyazaki, N.; Uehara-Ichiki, T.; Xing, L.; Bergman, L.; Higashiura, A.; Nakagawa, A.; Omura, T.; Cheng, R.H. Structural Evolution of Reoviridae Revealed by Oryzavirus in Acquiring the Second Capsid Shell. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11344–11353.

- Li, X.; Fang, Q. High-resolution 3D structures reveal the biological functions of reoviruses. Virol. Sin. 2013, 28, 318–325.

- Dryden, K.A.; Wang, G.; Yeager, M.; Nibert, M.L.; Coombs, K.M.; Furlong, D.B.; Fields, B.N.; Baker, T.S. Early Steps in Reovirus Infection Are Associated with Dramatic Changes in Supramolecular Structure and Protein Conformation: Analysis of Virions and Subviral Particles by Cryoelectron Microscopy and Image Reconstruction. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 122, 1023–1041.

- Snyder, A.J.; Wang, J.C.-Y.; Danthi, P. Components of the reovirus capsid differentially contribute to stability. J. Virol. 2018, 93.

- Kim, J.; Tao, Y.; Reinisch, K.M.; Harrison, S.C.; Nibert, M.L. Orthoreovirus and Aquareovirus core proteins: Conserved enzymatic surfaces, but not protein-protein interfaces. Virus Res. 2004, 101, 15–28.

- Roth, A.N.; Aravamudhan, P.A. Ins and outs of reovirus: Vesicular trafficking in viral entry and egress. Trends Microbiol. 2020.

- Barton, E.S.; Connolly, J.L.; Forrest, J.C.; Chappell, J.D.; Dermody, T.S. Utilization of sialic acid as a coreceptor enhances reovirus attachment by multistep adhesion strengthening. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 2200–2211.

- Schulz, W.L.; Haj, A.K.; Schiff, L.A. Reovirus uses multiple endocytic pathways for cell entry. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 12665–12675.

- Mainou, B.A.; Dermody, T.S. Transport to late endosomes is required for efficient reovirus infection. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 8346–8358.

- Amerongen, H.M.; Wilson, G.A.R.; Fields, B.N.; Neutral, M.R. Proteolytic Processing of Reovirus Is Required for Adherence to Intestinal M Cells. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 8428–8432.

- Shmulevitz, M.; Epand, R.F.; Epand, R.M.; Duncan, R. Structural and functional properties of an unusual internal fusion peptide in a nonenveloped virus membrane fusion protein. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 2808–2818.

- Tenorio, R.; de Castro, I.F.; Knowlton, J.J.; Zamora, P.F.; Sutherland, D.M.; Risco, C.; Dermody, T.S. Function, architecture, and biogenesis of reovirus replication neoorganelles. Viruses 2019, 11, 288.

- Furuichi, Y.; Shatkin, A.J. Differential synthesis of blocked and unblocked 5′-termini in reovirus mRNA: Effect of pyrophosphate and pyrophosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1976, 73, 3448–3452.

- Furuichi, Y.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Tomasz, J.; Shatkin, A.J. Mechanism of formation of reovirus mRNA 5′-terminal blocked and methylated sequence, m7GpppGmpC. J. Biol. Chem. 1976, 251, 5043–5053.

- Kozak, M.; Shatkin, A.J. Characterization of ribosome-protected fragments from reovirus messenger RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1976, 251, 4259–4266.

- Shatkin, A.J.; Both, G.W. Reovirus mRNA: Transcription and translation. Cell 1976, 7, 305–313.

- Furuichi, Y.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Tomasz, J.; Shatkin, A.J. Caps in eukaryotic mRNAs: Mechanism of formation of reovirus mRNA 5′-terminal m7GpppGm-C. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1976, 19, 3–20.

- Both, G.W.; Furuichi, Y.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Shatkin, A.J. Ribosome binding to reovirus mRNA in protein synthesis requires 5′ terminal 7-methylguanosine. Cell 1975, 6, 185–195.

- Both, G.W.; Lavi, S.; Shatkin, A.J. Synthesis of all the gene products of the reovirus genome in vivo and in vitro. Cell 1975, 4, 173–180.

- Chow, N.L.; Shatkin, A.J. Blocked and unblocked 5′ termini in reovirus genome RNA. J. Virol. 1975, 15, 1057–1064.

- Furuichi, Y.; Morgan, M.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Shatkin, A.J. Reovirus messenger RNA contains a methylated, blocked 5′-terminal structure: M-7G(5′)ppp(5′)G-MpCp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 362–366.

- Furuichi, Y.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Shatkin, A.J. 5′-Terminal m-7G(5′)ppp(5′)G-m-p in vivo: Identification in reovirus genome RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 742–745.

- Muthukrishnan, S.; Shatkin, A.J. Reovirus genome RNA segments: Resistance to S-1 nuclease. Virology 1975, 64, 96–105.

- Sen, G.C.; Lebleu, B.; Brown, G.E.; Rebello, M.A.; Furuichi, Y.; Morgan, M.; Shatkin, A.J.; Lengyel, P. Inhibition of reovirus messenger RNA methylation in extracts of interferon-treated Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1975, 65, 427–434.

- Miura, K.; Watanabe, K.; Sugiura, M.; Shatkin, A.J. The 5′-terminal nucleotide sequences of the double-stranded RNA of human reovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 3979–3983.

- Shatkin, A.J. Methylated messenger RNA synthesis in vitro by purified reovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 3204–3207.

- Furuichi, Y. "Methylation-coupled" transcription by virus-associated transcriptase of cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus containing double-stranded RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1974, 1, 809–822.

- Rhodes, D.P.; Moyer, S.A.; Banerjee, A.K. In vitro synthesis of methylated messenger RNA by the virion-associated RNA polymerase of vesicular stomatitis virus. Cell 1974, 3, 327–333.

- Wei, C.M.; Moss, B. Methylation of newly synthesized viral messenger RNA by an enzyme in vaccinia virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 3014–3018.

- Banerjee, A.K.; Ward, R.; Shatkin, A.J. Cytosine at the 3′-termini of reovirus genome and in vitro mRNA. Nat. New Biol. 1971, 232, 114–115.

- Borsa, J.; Grover, J.; Chapman, J.D. Presence of nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase activity in purified virions of reovirus. J. Virol. 1970, 6, 295–302.

- Desrosiers, R.C.; Sen, G.C.; Lengyel, P. Difference in 5′ terminal structure between the mRNA and the double-stranded virion RNA of reovirus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1976, 73, 32–39.

- Desrosiers, R.C.; Lengyel, P. Impairment of reovirus mRNA ‘cap’ methylation in interferon-treated mouse L929 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1979, 562, 471–480.

- Reeve, A.E.; Shatkin, A.J.; Huang, R.C. Guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) inhibits capping of reovirus mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 7018–7022.

- Kozak, M.; Shatkin, A.J. Identification of features in 5′ terminal fragments from reovirus mRNA which are important for ribosome binding. Cell 1978, 13, 201–212.

- Eaton, H.E.; Kobayashi, T.; Dermody, T.S.; Johnston, R.N.; Jais, P.H.; Shmulevitz, M. African swine fever virus NP868R capping enzyme promotes reovirus rescue during reverse genetics by promoting reovirus protein expression, virion assembly, and RNA incorporation into infectious virions. J. Virol. 2017, 91.

- Shmulevitz, M.; Pan, L.Z.; Garant, K.; Pan, D.; Lee, P.W. Oncogenic Ras promotes reovirus spread by suppressing IFN-beta production through negative regulation of RIG-I signaling. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 4912–4921.

- Goubau, D.; Schlee, M.; Deddouche, S.; Pruijssers, A.J.; Zillinger, T.; Goldeck, M.; Schuberth, C.; Van der Veen, A.G.; Fujimura, T.; Rehwinkel, J.; et al. Antiviral immunity via RIG-I-mediated recognition of RNA bearing 5′-diphosphates. Nature 2014, 514, 372–375.