Hypothalamic inflammation is a condition frequently observed in experimental models of diet-induced obesity (DIO) and obese humans. This inflammatory response is mainly triggered by excessive saturated fatty acids (SFAs) from the diet, which reach the neural tissue mainly through the median eminence (ME), where fenestrated vascular endothelium lacks a blood–brain barrier (BBB). Brain perivascular macrophages (PVMs) also react to excessive free fatty acids (FFAs) circulating in the blood vessels, with a consequent increase in BBB permeability. Glial cells, such as astrocytes and microglia, quickly sense and react to the presence of those SFAs in the hypothalamic parenchyma, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species (ROS). If the stimulus persists, the hypothalamic neuronal network may be damaged, resulting in neuro-inflammation, which eventually leads to energy balance disruption, and finally, to neuronal dysfunction/apoptosis.

- microglia

- gliosis

- hypothalamus

1. Introduction

Researchers have shown that hypothalamic inflammation initiates just a few hours/days upon high-fat feeding [5,15,19]. After the onset of the inflammatory response, bone marrow–derived cells (BMDC) and other peripheral immune cells, such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, and regulatory T (Treg) cells can arise into the hypothalamic parenchyma in a time-dependent manner, directly affecting glial functions [12,20,21]. To avoid further metabolic complications, hypothalamic neuronal and non-neuronal cells, along with peripheral immune cells, should act together in an orchestrated mode beginning with the earliest phase of the inflammatory response.

Researchers have shown that hypothalamic inflammation initiates just a few hours/days upon high-fat feeding [1][2][3]. After the onset of the inflammatory response, bone marrow–derived cells (BMDC) and other peripheral immune cells, such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, and regulatory T (Treg) cells can arise into the hypothalamic parenchyma in a time-dependent manner, directly affecting glial functions [4][5][6]. To avoid further metabolic complications, hypothalamic neuronal and non-neuronal cells, along with peripheral immune cells, should act together in an orchestrated mode beginning with the earliest phase of the inflammatory response.

The molecular mechanisms underlying microglial immune and metabolic interactions with other cell types under high-fat diet (HFD)-induced hypothalamic inflammation still require a more detailed exploration [22]. Recent data unveiling microglial diversity and signatures throughout the brain have contributed to the development of novel state-of-the-art approaches in experimental studies, which can be valuable for this field in the coming years.

The molecular mechanisms underlying microglial immune and metabolic interactions with other cell types under high-fat diet (HFD)-induced hypothalamic inflammation still require a more detailed exploration [7]. Recent data unveiling microglial diversity and signatures throughout the brain have contributed to the development of novel state-of-the-art approaches in experimental studies, which can be valuable for this field in the coming years.

2. Microglial Signature Changes Upon HFD-Induced Hypothalamic Inflammation

There are sufficient clues indicating that microglia present distinct activated signatures under inflammatory conditions. Sousa et al. [72] performed scRNA-seq to investigate the microglial profile in the brain of LPS-injected mice. They found that microglia isolated from these mice exhibit a downregulation of their homeostatic signature together with an upregulation of inflammatory genes. They obtained this data by excluding other CNS-resident immune cells and peripheral cells in the analysis.

There are sufficient clues indicating that microglia present distinct activated signatures under inflammatory conditions. Sousa et al. [8] performed scRNA-seq to investigate the microglial profile in the brain of LPS-injected mice. They found that microglia isolated from these mice exhibit a downregulation of their homeostatic signature together with an upregulation of inflammatory genes. They obtained this data by excluding other CNS-resident immune cells and peripheral cells in the analysis.

To explore deeply how HFD-induced inflammation affects microglial transcriptomics, we have searched for transcriptomic data published from HFD-fed rodents at a single-cell resolution. As already mentioned, Campbell et al. [108] performed Drop-seq profiling on the ARC and ME from mice across different feeding conditions, including 1-week HFD (60% calories from fat). They found that microglia present high P2ry12 and low Mrc1 while PVMs show low P2ry12 and high Mcr1. However, when comparing low fat diet–fed mice with HFD-fed mice, they found the transcripts from these clusters downregulated, but they did not describe which HFD-sensitive genes were modulated.

To explore deeply how HFD-induced inflammation affects microglial transcriptomics, we have searched for transcriptomic data published from HFD-fed rodents at a single-cell resolution. As already mentioned, Campbell et al. [9] performed Drop-seq profiling on the ARC and ME from mice across different feeding conditions, including 1-week HFD (60% calories from fat). They found that microglia present high P2ry12 and low Mrc1 while PVMs show low P2ry12 and high Mcr1. However, when comparing low fat diet–fed mice with HFD-fed mice, they found the transcripts from these clusters downregulated, but they did not describe which HFD-sensitive genes were modulated.

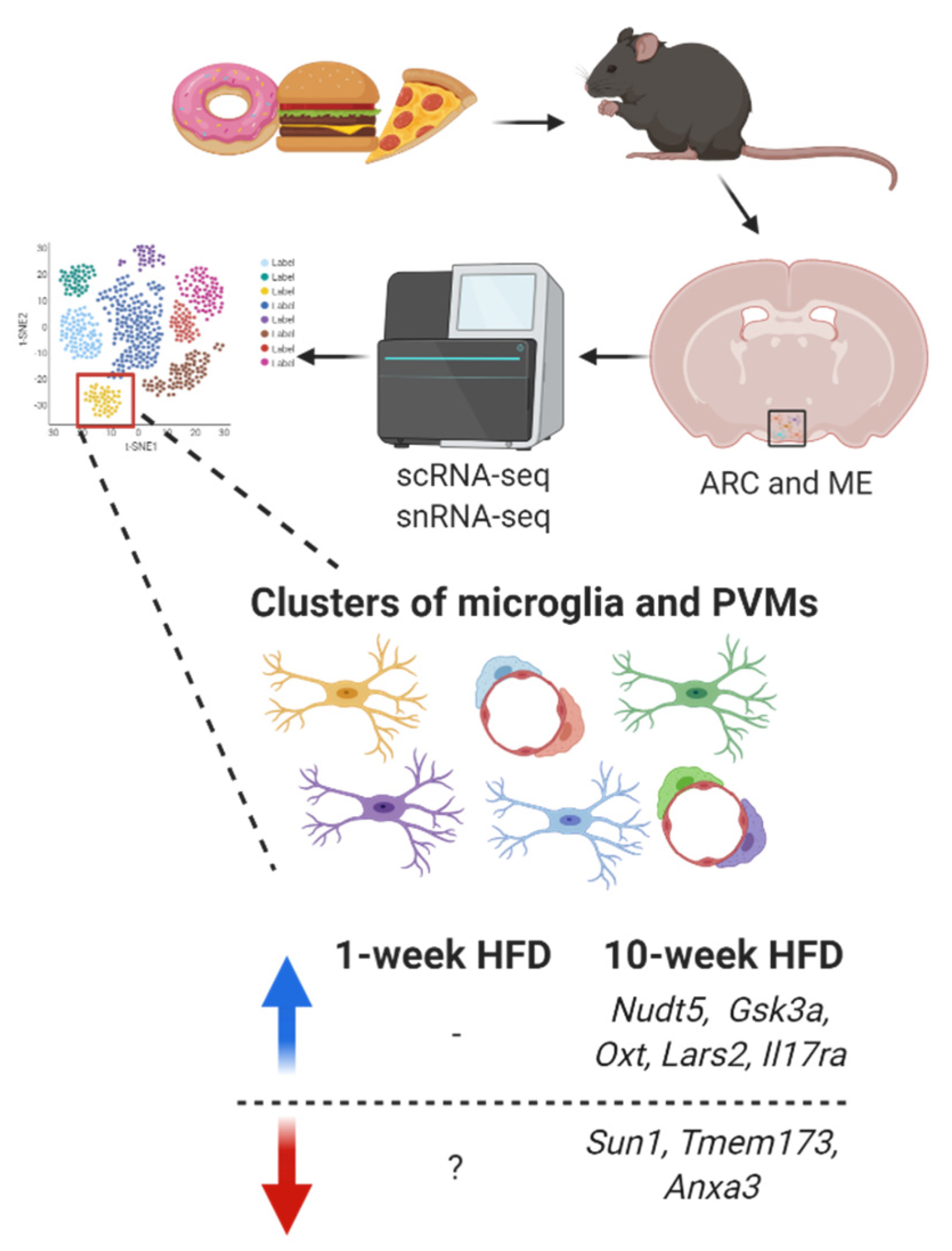

On the other hand, in an experimental model of prolonged high-fat feeding, C57BL/6J male mice were fed a HFD (45% calories from fat) for 10 weeks, and their ARC was collected for single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) [156]. After consuming a HFD for 10-weeks, some genes were upregulated in the cluster of microglia (Nudt5, Gsk3a, Oxt, Lars2, and Il17ra) while other genes (Sun1, Tmem173 and Anxa3) were downregulated (Figure 5).

On the other hand, in an experimental model of prolonged high-fat feeding, C57BL/6J male mice were fed a HFD (45% calories from fat) for 10 weeks, and their ARC was collected for single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) [10]. After consuming a HFD for 10-weeks, some genes were upregulated in the cluster of microglia (Nudt5, Gsk3a, Oxt, Lars2, and Il17ra) while other genes (Sun1, Tmem173 and Anxa3) were downregulated (Figure 1).

Figure 51. Transcriptomic signature changes in microglia (ramified cells) and perivascular macrophages (PVMs) (elongated cells around blood vessels) from the arcuate nucleus (ARC) and median eminence (ME) under short-term and prolonged HFD-induced hypothalamic inflammation. Blue arrow indicates upregulation while red arrow indicates downregulation.

Some of them have also been described in obesity-related studies. Methylation in Lars2, which is a mitochondrial gene, has been reported in an epigenome-wide association study as a gene associated with increased body mass index and waist circumference [157]. The receptor for interleukin-17 (IL-17), known as Il17ra, is found in pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons in the hypothalamus and modulates food intake after IL-17 binding, without affecting whole-body energy expenditure [158].

Some of them have also been described in obesity-related studies. Methylation in Lars2, which is a mitochondrial gene, has been reported in an epigenome-wide association study as a gene associated with increased body mass index and waist circumference [11]. The receptor for interleukin-17 (IL-17), known as Il17ra, is found in pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons in the hypothalamus and modulates food intake after IL-17 binding, without affecting whole-body energy expenditure [12].

Although the ARC is the main nucleus involved in energy metabolism and food intake control, functional impairments in neurons and glial cells from other hypothalamic nuclei are also involved in DIO establishment [159,160]. Recently, Rossi et al. [161] identified in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) thousands of genes altered upon prolonged HFD intake. This research article highlighted only dynamic transcriptomic details in neurons; thus, the authors did not deeply explore the transcription differences in microglia and other myeloid cell lineages upon. However, the authors distinctively represent these cells by using Cx3cr1 hallmark for microglia and Lys2 for myeloid cells, which was not considered in data from ARC published by Deng et al. [156].

Although the ARC is the main nucleus involved in energy metabolism and food intake control, functional impairments in neurons and glial cells from other hypothalamic nuclei are also involved in DIO establishment [13][14]. Recently, Rossi et al. [15] identified in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) thousands of genes altered upon prolonged HFD intake. This research article highlighted only dynamic transcriptomic details in neurons; thus, the authors did not deeply explore the transcription differences in microglia and other myeloid cell lineages upon. However, the authors distinctively represent these cells by using Cx3cr1 hallmark for microglia and Lys2 for myeloid cells, which was not considered in data from ARC published by Deng et al. [10].

Interestingly, from all transcriptomic data obtained from the ARC–ME or LHA, researchers can apply a bioinformatic analysis to better investigate how microglia and other myeloid cells changes upon prolonged HFD. In the face of the recent and continuous development of novel transcriptomic tools, such as scRNA-seq, snRNA-seq, and CyTOF, among others, future studies should be conducted to better clarify the main changes in microglial signature throughout the hypothalamus under different stages of high-fat feeding. For accurate data interpretation, microglia and other CNS-associated macrophages should be clustered and analyzed separately. The detailed identification of those cells will be valuable to answer more precisely several outstanding questions.

3. Conclusions

Microglia were first recognized as macrophage-like cells from the CNS a century ago, but for a long time their complexity was unknown. Luckily, the development of assorted transcriptomic tools has boosted the knowledge about these cells in recent years. Currently, it is well known that the hypothalamus presents several microglial subsets that can be identified by their hallmarks: Iba1, Cx3Cr1, Tmem119, P2ry12, Trem2, Hexb, and Csfr1, among many other. DM are also found in the hypothalamic area, but their roles in HFD-induced inflammation has been poorly investigated. In fact, microglia play a pivotal role in different stages of the hypothalamic inflammatory process, but how each microglial subtype reacts to SFAs from the diet, communicates with other cells, or even leads to the recruitment of peripheral myeloid cells remains to be explored. Beyond microglia, astrocytes also display high heterogeneity throughout the CNS, and in the hypothalamus, its diversity and its crosstalk with microglia require to be better elucidated. Novel experimental models for manipulating or labelling microglia have been developed and will be useful to answer that question in forthcoming research. On the other hand, the hypothalamic microglial signature under HFD-induced hypothalamic inflammation should still be further studied using different transcriptomic approaches. Together, these advances will allow researchers to take full advantage of crucial insights we have gained about microglial heterogeneity (provided by transcriptomic data) and to exploit this knowledge to determine the mechanisms by which microglia are involved in the inflammatory process observed in obesity.

References

- Thaler, J.P.; Yi, C.X.; Schur, E.A.; Guyenet, S.J.; Hwang, B.H.; Dietrich, M.O.; Zhao, X.; Sarruf, D.A.; Izgur, V.; Maravilla, K.R.; et al. Obesity Is Associated with Hypothalamic Injury in Rodents and Humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 153–162.

- Cansell, C.; Stobbe, K.; Sanchez, C.; Le Thuc, O.; Mosser, C.A.; Ben-Fradj, S.; Leredde, J.; Lebeaupin, C.; Debayle, D.; Fleuriot, L.; et al. Dietary Fat Exacerbates Postprandial Hypothalamic Inflammation Involving Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein-Positive Cells and Microglia in Male Mice. Glia 2020.

- Carraro, R.S.; Souza, G.F.; Solon, C.; Razolli, D.S.; Chausse, B.; Barbizan, R.; Victorio, S.C.; Velloso, L.A. Hypothalamic Mitochondrial Abnormalities Occur Downstream of Inflammation in Diet-Induced Obesity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 460, 238–245.

- Lee, C.H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, Y.S.; Kang, G.M.; Lim, H.S.; Lee, S.H.; Song, D.K.; Kwon, O.; Hwang, I.; Son, M.; et al. Hypothalamic Macrophage Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Mediates Obesity-Associated Hypothalamic Inflammation. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 934–946.e5.

- Valdearcos, M.; Douglass, J.D.; Robblee, M.M.; Dorfman, M.D.; Stifler, D.R.; Bennett, M.L.; Gerritse, I.; Fasnacht, R.; Barres, B.A.; Thaler, J.P.; et al. Microglial Inflammatory Signaling Orchestrates the Hypothalamic Immune Response to Dietary Excess and Mediates Obesity Susceptibility. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 185–197.e3.

- Greenhalgh, A.D.; David, S.; Bennett, F.C. Immune Cell Regulation of Glia during CNS Injury and Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 21, 139–152.

- Mendes, N.F.; Kim, Y.-B.; Velloso, L.A.; Araújo, E.P. Hypothalamic Microglial Activation in Obesity: A Mini-Review. Front. Neurosci. 2018.

- Sousa, C.; Golebiewska, A.; Poovathingal, S.K.; Kaoma, T.; Pires-Afonso, Y.; Martina, S.; Coowar, D.; Azuaje, F.; Skupin, A.; Balling, R.; et al. Single-cell Transcriptomics Reveals Distinct Inflammation-induced Microglia Signatures. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19.

- Campbell, J.N.; Macosko, E.Z.; Fenselau, H.; Pers, T.H.; Lyubetskaya, A.; Tenen, D.; Goldman, M.; Verstegen, A.M.J.; Resch, J.M.; McCarroll, S.A.; et al. A Molecular Census of Arcuate Hypothalamus and Median Eminence Cell Types. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 484–496.

- Deng, G.; Morselli, L.L.; Wagner, V.A.; Balapattabi, K.; Sapouckey, S.A.; Knudtson, K.L.; Rahmouni, K.; Cui, H.; Sigmund, C.D.; Kwitek, A.E.; et al. Single-Nucleus RNA Sequencing of the Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus of C57BL/6J Mice after Prolonged Diet-Induced Obesity. Hypertension 2020, 76, 589–597.

- Dhana, K.; Braun, K.V.E.; Nano, J.; Voortman, T.; Demerath, E.W.; Guan, W.; Fornage, M.; Van Meurs, J.B.J.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Hofman, A.; et al. An Epigenome-Wide Association Study of Obesity-Related Traits. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 1662–1669.

- Nogueira, G.; Solon, C.; Carraro, R.S.; Engel, D.F.; Ramalho, A.F.; Sidarta-Oliveira, D.; Gaspar, R.S.; Bombassaro, B.; Vasques, A.C.; Geloneze, B.; et al. Interleukin-17 Acts in the Hypothalamus Reducing Food Intake. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 272–285.

- Gumbs, M.C.R.; Eggels, L.; Kool, T.; Unmehopa, U.A.; van den Heuvel, J.K.; Lamuadni, K.; Mul, J.D.; la Fleur, S.E. Neuropeptide Y Signaling in the Lateral Hypothalamus Modulates Diet Component Selection and Is Dysregulated in a Model of Diet-Induced Obesity. Neuroscience 2020, 447, 28–40.

- Li, M.M.; Madara, J.C.; Steger, J.S.; Krashes, M.J.; Balthasar, N.; Campbell, J.N.; Resch, J.M.; Conley, N.J.; Garfield, A.S.; Lowell, B.B. The Paraventricular Hypothalamus Regulates Satiety and Prevents Obesity via Two Genetically Distinct Circuits. Neuron 2019, 102, 653–667.e6.

- Rossi, M.A.; Basiri, M.L.; McHenry, J.A.; Kosyk, O.; Otis, J.M.; Van Den Munkhof, H.E.; Bryois, J.; Hübel, C.; Breen, G.; Guo, W.; et al. Obesity Remodels Activity and Transcriptional State of a Lateral Hypothalamic Brake on Feeding. Science 2019, 364, 1271–1274.