Programmed cell death (PCD) is a genetically controlled suicide process present in all living beings with the scope of eliminating cells unnecessary or detrimental for the proper develop-ment of the organism. In plants, PCD plays a pivotal role in many developmental processes such as sex determination, senescence, and aerenchyma formation and is involved in the defense re-sponses against abiotic and biotic stresses.

- cell cultures

- programmed cell death

- reactive oxygen species

- reactive nitrogen species

1. Introduction

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a genetically controlled suicide process present in all living beings with the scope of eliminating cells unnecessary or detrimental for the proper development of the organism. PCD plays a pivotal role in the plant lifestyle and it is involved in several developmental (senescence, formation of tracheary elements, sex determination, aerenchyma formation, endosperm and aleuron maturation) and pathological contexts (response to stresses and to pathogen attack) [1,2][1][2]. Thus, its study is a main goal for plant scientists. PCD process is organized in three phases. The first one is the induction phase, where the cells receive a wide range of extra- or intracellular signals (developmental input, pathogen attack, signals from neighboring cells, abiotic or biotic stresses). The second one is the effector phase, where the signals are elaborated to activate the death machinery. The third one is the degradation phase, where the activity of the death machinery causes the controlled destructuring of fundamental cell components [3]. The degradation phase shows a set of hallmarks that can be used to identify cells undergoing PCD. These hallmarks include shrinkage of cellular and nuclear membrane, activation of specific cysteine proteases called caspases, and activation of specific endonucleases able to cleave DNA in controlled fragments (laddering) [3]. Unlike animals, where well-described forms of PCD (for example apoptosis) are reported, in plants, the PCD process is still poorly understood and the term PCD is widely used to describe cell death observed in different tissues and organs. At present, in plants, at least three forms of PCD have been described and cataloged on the basis of both cellular morphology and the main cellular compartment involved in the process. The “nucleus first form” is observable during the hypersensitive response to pathogen attack and it is similar to animal apoptosis for the presence of specific hallmarks, involvement of mitochondria included. The “chloroplast first form” is observable during foliar senescence, while the “vacuole first form” is observable during the maturation of vascular elements and during aerenchyma formation [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][4].

2. PCD Induced in Cell Cultures by Biotic Stress

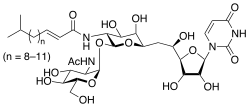

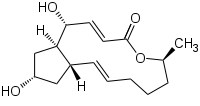

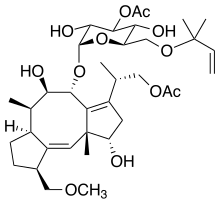

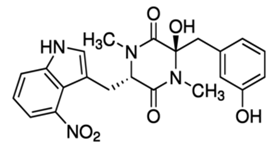

Several toxins and metabolic products obtained by microorganisms and fungi can induce PCD in cell cultures, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Biotic programmed cell death (PCD) inducers in plant cell cultures.

|

Plant Species |

PCD Induced by |

Main Characteristics of Induced PCD |

Reference |

|

Acer pseudoplatanus L. |

Tunicamycin |

H2O2 accumulation, changes in cell and nucleus morphology, DNA fragmentation |

[7] |

|

Acer pseudoplatanus L. |

Brefeldin A |

H2O2 accumulation, changes in cell and nucleus morphology, DNA fragmentation |

[7] |

|

Acer pseudoplatanus L. |

Fusicoccin |

H2O2 accumulation, changes in cell and nucleus morphology, DNA laddering |

[8] |

|

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. |

Thaxtomin A |

Activation of gene transcription and protein synthesis, DNA fragmentation |

[9] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

Metabolic products present in the Alternaria alternata culture filtrate |

Cytoplasm shrinkage, chromatin condensation, DNA laddering |

[10] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. NC89 |

Fusaric acid |

H2O2 accumulation, lipid peroxidation, caspase-3-like protease activity, mitochondrial dysfunction |

[11] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

Culture filtrates of Erwinia carotovora |

Changes in vacuole shape, endoplasmic actin filaments disassembly |

[12] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

Deoxynivalenol |

H2O2 accumulation, activation of gene transcription, mitochondrial dysfunction |

[13] |

|

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. |

Ceramides |

Generation of Ca2+ transient, H2O2 accumulation |

[14] |

|

Solanum lycopersicum L. |

Phosphatidic acid |

ROS and ethylene accumulation, protoplast shrinkage, nucleus condensation, caspase-3-like protease activity |

[15] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

Acrolein |

ROS accumulation, caspase-3-like protease activity |

[16] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

Narciclasin |

Cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and nuclear DNA degradation |

[17] |

|

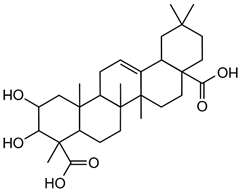

Populus alba L. |

Medicagenic acid |

ROS and RNS accumulation, changes in cell and nucleus morphology, chromatin condensation |

[18] |

|

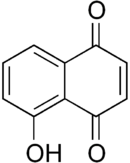

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

Juglone |

ROS accumulation, DNA fragmentation and hypomethylation |

[19] |

|

Vitis labrusca L. |

Alanine |

DNA fragmentation, expression of defense-related genes, accumulation of phenolic compounds |

[20] |

|

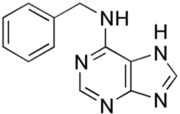

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. |

6-benzylaminopurine |

Changes in nucleus morphology, DNA laddering, activation of gene transcription |

[21] |

|

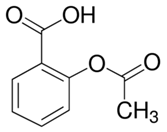

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. |

Acetylsalicilic acid |

Cell shrinkage, nuclear DNA degradation, mitochondrial dysfunction, induction of caspase-like activity |

[22] |

|

Acer pseudoplatanus L.

|

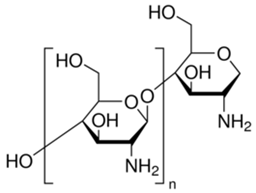

Chitosan |

ROS and RNS accumulation, nuclear DNA degradation, caspase-3-like protease activity, mitochondrial dysfunction, expression of defense-related genes |

[23] |

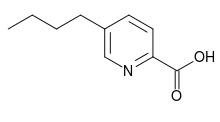

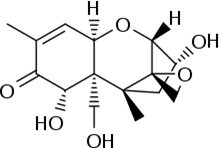

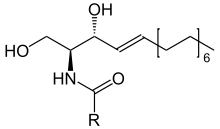

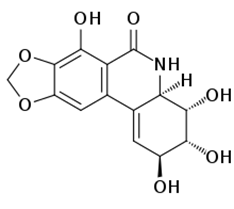

For example, in Acer pseupdoplatanus L.-cultured cells, tunicamycin, an inhibitor of N-linked protein glycosylation produced by Streptomyces lysosuperificus, and brefeldin A, an inhibitor of protein trafficking from the Golgi apparatus produced by Eupenicillium brefeldianum, induce a PCD with apoptotic features such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, changes in cell and nucleus morphology, and specific DNA fragmentation [7]. In the same experimental material, fusicoccin a well-known activator of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase produced by Phomopsis amygdali induces PCD with similar characteristics [8]. The well-identified target of these molecules permitted to test the role of specific cell compartments or physiological functions in the induction, development, and execution of plant PCD process. In particular, investigation conducted with fusicoccin showed that the phytotoxin-induced PCD involves changes in actin cytoskeleton [24] and utilizes the plant hormone ethylene as regulative molecule in addition to ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [25]. Interestingly, inhibition of cytochrome c release from the mitochondrion by cyclosporin A markedly prevents the fusicoccin-induced PCD [26], and recently a possible role as signaling molecule for peroxynitrite has been proposed [27]. These results also sustain the fundamental role of cytochrome c and peroxynitrite in the induction of PCD process in plants. In Arabidopsis thaliana cultures, thaxtomin A, an inhibitor of cellulose biosynthesis produced by Streptomyces scabiei, induces a PCD dependent on active gene transcription and de novo protein synthesis and that displays apoptotic-like features such as specific DNA fragmentation [9]. Interestingly, addition of auxin to Arabidopsis cell cultures prevents thaxtomin-induced PCD possibly by stabilizing the plasma membrane–cell wall–cytoskeleton continuum [28]. In tobacco BY-2 (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2) cell suspensions metabolic products present in the Alternaria alternata culture filtrate induce a PCD dependent on ROS generation that shows cytoplasm shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and DNA laddering [10]. Interestingly, the PCD induced in tobacco BY-2 cells by Pectobacterium carotovorum and Pectobacterium atrosepticum is reduced by culture filtrate of non-pathogenic Streptomyces sp. OE7 that through cytosolic Ca2+ changes and generation of ROS induces defense responses [29]. This highlights the complexity of the interactions between microorganisms and plants and the need for further investigations. In tobacco cv. NC89-cultured cells, fusaric acid, a non-specific toxin produced mainly by Fusarium spp., causes PCD with mechanism that is not well understood that, however, involves ROS overproduction and mitochondrial dysfunction [11]. In fact, pre-treatment of tobacco cells with the antioxidant molecule ascorbic acid and with the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase inhibitor diphenyl iodonium significantly reduces the fusaric acid-induced accumulation of dead cells as well as the increase in caspase-3-like protease activity. Moreover, oligomycin and cyclosporine A, inhibitors of the mitochondrial ATP synthase and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, respectively, also reduce the rate of fusaric acid-induced cell death [11]. PCD induced in cell cycle-synchronized tobacco BY-2 cells by application of culture filtrates of Erwinia carotovora involves changes in vacuole shape and disassembly of endoplasmic actin filaments [12]. In tobacco BY-2 cultures, deoxynivalenol, a mycotoxin synthesized by Fusarium culmorum and Fusarium graminearum, induces a PCD sustained by different cross-linked pathways involving ROS generation linked, at least partly, to a mitochondrial dysfunction and to transcriptional downregulation of the alternative oxidase (Aox1) gene and showing regulation of ion channel activities participating in cell shrinkage [13]. Interestingly, this mycotoxin is also able to induce PCD in animal cells, but with different characteristics. This suggests the presence of different ways to induce PCD between animals and plants (original articles cited in [13]). Some metabolites able to induce PCD in plant cultured cells can originate from the degradation of cellular components or are produced by the primary and secondary metabolism of microorganisms and plants. For example, ceramides, lipids derived from the membranes of eukaryotic cells, can induce PCD in Arabidopsis cultures in a Ca2+-dependent manner. In fact, the calcium channel-blocker lanthanum chloride substantially reduces the amount of ceramide-induced cell death [14]. Interestingly, in the same material, sphingolipids can reduce apoptotic-like PCD induced by different treatments, ceramides and heat stress included [30]. Moreover, in tomato suspensions, cell death induced by camptothecin, fumonisin B1, and CdSO4 is regulated by phosphatidic acid. This cell death involves ROS and ethylene, depends on caspase-like proteases, and expresses morphological features of apoptotic-like PCD such as protoplast shrinkage and nucleus condensation [15]. Reactive carbonyl species (namely, acrolein, shown in Table 1) derived from lipid peroxidation can activate caspase-3-like proteases to initiate PCD in tobacco BY-2 cultures [16]. In the same experimental material, narciclasine (NCS), a plant growth inhibitor isolated from the secreted mucilage of Narcissus tazetta bulbs, can induce typical PCD-associated morphological and biochemical changes, namely, cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and nuclear DNA degradation [17]. Among primary and secondary metabolites, the triterpene saponins (namely, medicagenic acid, shown in Table 1) from alfalfa (Medicago sativa) applied to Populus alba cell cultures induce a PCD dependent on RNS and ROS production and showing changes in nucleus morphology and chromatin condensation [18]. In tobacco BY-2 cultures, juglone (5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone) causes cell death with ROS overproduction accompanied by formation of apoptic-like nuclear bodies (indication of DNA fragmentation) and DNA hypomethylation [19]. In Vitis labrusca suspension cultures, L-alanine is the only amino acid able to induce PCD accompanied by DNA fragmentation, expression of defense-related genes, and accumulation of phenolic compounds [20] [31]. Plant phytoregulators can also activate PCD in plant cell cultures. For example, high levels of cytokinins (namely, 6-benzylaminopurine, shown in Table 1) induce PCD in Arabidopsis cultures by accelerating a senescence process characterized by DNA laddering and expression of specific senescence markers [21]. In the same material acetylsalicylic acid, a derivative from the plant hormone salicylic acid induces typical PCD-linked morphological and biochemical changes, namely, cell shrinkage, nuclear DNA degradation, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, cytochrome c release from mitochondria, and induction of caspase-like activity [22]. Finally, in Acer pseudoplatanus cultures, chitosan, the non-toxic and inexpensive compound obtained by deacetylation of chitin, the main component of the exoskeleton of arthropods as well as of the cell walls of many fungi, induces a PCD mediated by ROS and RNS accumulation and showing changes in gene expression and specific DNA fragmentation [23].

3. PCD Induced in Cell Cultures by Abiotic Stress

Several abiotic stresses ranking from different chemicals such as heavy metals and dyes to ambient growth conditions can induce PCD in plant cell cultures, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Abiotic PCD inducers in plant cell cultures.

|

Plant Species |

PCD Induced by |

Main Characteristics of Induced PCD |

Reference |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

Cadmium ions |

Changes in cell and nucleus morphology, appearance of autophagic bodies |

[31] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

Aluminium oxide nanoparticles |

Caspase-like protease activity, mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA fragmentation |

[32] |

|

Viola tricolor L. |

Zinc and lead ions |

Changes in cell and nucleus morphology, DNA fragmentation, caspase-like and papain-like cysteine protease activity |

[33] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

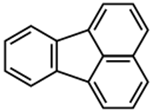

Fluoranthene |

ROS accumulation, lipid peroxidation, caspase-3-like protease activity, DNA fragmentation |

[34] |

|

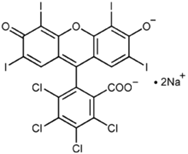

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. |

Rose Bengal |

ROS accumulation, lipid peroxidation, specific gene activation |

[35] |

|

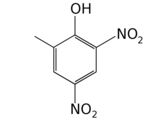

Glycine max (L.) Merr. |

Dinitro-o-cresol |

Mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA fragmentation, caspase-3-like protease activity |

[36] |

|

Populus euphratica Oliv. |

1-Butanol |

Cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, nuclear DNA degradation, caspase-3-like protease activity |

[37] |

|

Populus euphratica Oliv. |

ATP (externally added) |

Elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ levels, ROS accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction |

[38] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

Heat stress |

ROS accumulation, cytoplasmic shrinkage, DNA fragmentation, caspase-3-like protease activity, mitochondrial dysfunction, induction of defense-related genes |

[39] |

|

Cakile maritime Scop. Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. |

Salt stress |

ROS accumulation, lipid peroxidation, specific gene activation, caspase-3-like protease activity, mitochondrial dysfunction |

[40] |

|

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. |

Ozone |

ROS accumulation, Ca2+ influx, changes in cell and nucleus morphology |

[41] |

|

Vitis vinifera L. |

Darkness (in senescent cultures) |

ROS accumulation, DNA fragmentation, caspase-3-like protease activity, mitochondrial dysfunction |

[42] |

|

Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bright Yellow 2 |

UV-B |

ROS accumulation, DNA fragmentation, mitochondrial dysfunction |

[43] |

|

Pinus pinaster Ait. |

Sugar and phosphate depletion |

Changes in cell and nucleus morphology, DNA fragmentation, DNA laddering |

[44] |

|

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. |

polyethylene glycol, mannose, H2O2, ethylene * |

Changes in cell and nucleus morphology, DNA fragmentation, specific gene activation. * Cell plasma membrane permeabilization, ROS overproduction, severe oxidative stress |

[45] |

* Main characteristics of PCD induced by ethylene.

For example, cadmium is a potent inducer of PCD in plants and in tobacco BY-2-cultured cells; this process involves alterations in cell and nucleus morphology and appearance of autophagic bodies [32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][31]. In the same experimental material, aluminum oxide nanoparticles induce a PCD form closely connected to loss of mitochondrial potential, enhancement of caspase-like activity, and DNA fragmentation [32]. In Viola tricolor L.-cultured cells, zinc and lead ions stimulate a PCD form showing DNA fragmentation and activation of caspase-like and papain-like cysteine proteases [33]. Interestingly, the indoleamine melatonin protects tobacco BY-2-cultured cells from lead stress by inhibiting cytochrome c release, thereby preventing the activation of the cascade of processes leading to cell death [46]. Other important environmental pollutants able to induce PCD in cultured plant cells are aromatic compounds. In fact, fluoranthene causes DNA fragmentation and oxidative stress in tobacco BY-2 suspension cultures [34]. Rose Bengal dye in Arabidopsis thaliana cell suspension cultures requires functional chloroplasts to activate a PCD process showing ROS accumulation and specific gene activation [35], and the herbicide dinitro-o-cresol induces DNA fragmentation, activation of caspase-3-like proteins, and release of cytochrome c from mitochondria in soybean (Glycine max) suspension cell cultures [36]. Other chemicals able to induce PCD are 1-butanol, which in Populus euphratica cell cultures causes shrinkage of the cytoplasm, DNA fragmentation, condensed or stretched chromatin, and the activation of caspase-3-like proteases [37] and ATP, which when externally added to the same cell cultures causes elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ levels, ROS accumulation, and cytochrome c release [38]. As far as environmental conditions are concerned, heat stress (HS) is a potent inducer of PCD in plants, where it causes important yield losses. HS study in cultured cells has permitted to elucidate some aspects of its induction, thus helping in the reduction of losses. For example, in tobacco BY-2-cultured cells, HS induces PCD, showing apoptotic features such as cytoplasmic shrinkage, DNA fragmentation, ROS accumulation, activation of caspase-3-like proteases, and induction of defense-related genes [39,47]. Some of these effects of HS are prevented by selenium [47] and depend on peroxynitrite accumulation [48], thus sustaining the fundamental role of oxidative stress in the induction of HS-dependent PCD. This view is also sustained by the analysis of the soluble proteome of tobacco cells subjected to HS and by custom microarray analysis of gene expression during PCD of Arabidopsis thaliana-cultured cells. Both these molecular investigations show the induction of genes related to oxidative stress resistance [49,50]. Another environmental condition that is able to induce PCD is salinity. Interestingly, the comparison of the responses to salt stress of suspension-cultured cells from the halophyte Cakile maritima and the glycophyte Arabidopsis thaliana shows that both species present similar dysfunction of mitochondria and caspase-3-like activation but the salt-tolerant C. maritima can better resist to stress due to a higher ascorbate pool able to mitigate the oxidative stress generated in response to NaCl [40]. O3 exposure also induces PCD dependent on ROS generation in cell suspensions of Arabidopsis thaliana [41]. Light also seems to be an important environmental factor able to regulate PCD. Darkness enhances cell death but flavonoids and darkness lower PCD during senescence of Vitis vinifera cell suspensions [42], pointing out the complexity of PCD regulation in plants. In tobacco BY 2-cultured cells, UV-B overexposure induces a PCD form showing typical apoptotic morphological features such as cell shrinkage, condensation of chromatin in perinuclear areas, and formation of micronuclei [43]. The nutritional aspect is also important. In fact, simultaneous depletion of sugar and phosphate is associated with PCD, showing nuclear DNA degradation in suspension cultures of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait.) [44].

Very interesting results have been obtained from experiments performed in a cell cycle-synchronized Arabidopsis thaliana cell suspension culture treated with four physiological stressors (polyethylene glycol, mannose, H2O2, ethylene) in the late G2 phase. In these cultures, depending on the cell death inducer, there are significant differences in the appearance of specific PCD hallmarks. In fact, polyethylene glycol, mannose, and H2O2 cause DNA fragmentation and cell permeability to vital stains, and produce corpse morphology corresponding to apoptotic-like PCD. Instead, ethylene (a plant hormone associated with senescence) causes permeability of cells to vital stains without concomitant nuclear DNA fragmentation and cytoplasmic retraction but with very high ROS production, leading to severe oxidative stress [45]. Similarly, in tobacco BY 2-cultured cells, zinc oxide nanoparticles cause cell death depending on oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation [51], and in grapevine suspension cell cultures, different concentrations of silver ions cause cell death with different characteristics [52]. Thus, depending on the genotype/species and level of stress, the same factors may cause different responses. Low stress levels permit the repair of cell damage, moderate stress levels may induce PCD, and uncontrollable stress levels potentially lead to accidental cell death (necrosis, see also Section 5). This is particularly evident with abiotic stressors such as heavy metals and externally added compounds such as plant hormones and H2O2 (original articles cited in [53]).

References

- Tóth, G.; Hermann, T.; Szatmári, G.; Pásztor, L. Maps of heavy metals in the soil of European Union and proposed priority areas for detailed assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 565, 1054–1062.

- Yabe, J.; Ishizuka, M.; Umemura, T. Current level of heavy metal pollution in Africa. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2010, 72, 1257–1263.

- Tong, S.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Tudi, M.; Yang, L. Concentration, special distribution, contamination degree and human health risk assessment of heavy metals in urban soils across China between 2003 and 2019—A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3099.

- Weissmanová, H.D.; Pavlovskỳ, J. Indices of soil contamination by heavy metals—Methodology of calculation for pollution assessment (minireview). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 616.

- Afonne, O.J.; Ifebida, E.C. Heavy metals risks in plant foods—Need to step up precautionary measures. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2020, 22, 1–6.

- Sharma, A.; Nagpal, A.K. Contamination of vegetables with heavy metals across the globe: Hampering food security goal. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 391–403.

- Kumar, S.; Prasad, S.; Yadav, K.K.; Shrivastava, M.; Gupta, N.; Nagar, S.; Bach, Q.-V.; Kamyab, H.; Khana, S.S.; Yadav, S.; et al. Hazardous heavy metals contamination of vegetables and food chain: Role of sustainable remediation approaches—A re-view. Environ. Res. 2019, 179, 108792.

- Striker, G.G. Time is on our side: The importance of considering a recovery periods when assessing flooding tolerance in plants. Ecol. Res. 2011, 27, 983–987.

- Andresen, E.; Peiter, E.; Kűpper, H. Trace metal metabolism in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 5, 909–954.

- Ghori, N.-H.; Ghori, T.; Hayat, M.Q.; Imadi, S.R.; Gul, A.; Altay, V.; Ozturk, M. Heavy metal stress and response in plants. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1807–1828.

- Kűpper, H.; Andresen, E. Mechanisms of metal toxicity in plants. Metallomics 2016, 8, 269.

- Tamás, M.J.; Sharma, S.K.; Ibstedt, S.; Jacobson, T.; Christen, P. Heavy metals and metalloids as a cause for protein misfold-ing and aggregation. Biomolecules 2014, 4, 252–267.

- Rivetta, A.; Negrini, N.; Cocucci, M. Involvement of Ca2+-calmodulin in Cd2+ toxicity during the early phases of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seed germination. Plant Cell Environ. 1997, 20, 600–608.

- Kűpper, H.; Kűpper, F.; Spiller, M. Environmental relevance of heavy metal-substituted chlorophylls using example of water plants. J. Exp. Bot. 1996, 47, 259–266.

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M.; Fotopulos, V. Reac-tive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: Revising the crucial role of universal defense regu-lators. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681.

- Rucińska-Sobkowiak, R. Water relations in plants subjected to heavy metal stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 257.

- Krzesłowska, M. The cell wall in plant cell wall response to trace metals: Polysaccharide remodelling and its role in defense strategy. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 35–51.

- Rucińska-Sobkowiak, R.; Nowaczyk, G.; Krzesłowska, M.; Rabęda, I.; Jurga, S. Water status and water diffusion transport in lupine roots exposed to lead. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 87, 100–109.

- Samardakiewicz, S.; Krzesłowska, M.; Bilski, H.; Bartosiewicz, R.; Woźny, A. Is callose a barrier for lead ions entering Lemna minor L. root cells? Protoplasma 2012, 249, 347–351.

- Przedpelska-Wasowicz, E.M.; Wierzbicka, M. Gating of aquaporins by heavy metals in Allium cepa L. epidermal cells. Proto-plasma 2011, 248, 663–671.

- Lamoreaux, R.J.; Chaney, W.R. Growth and water movement in silver maple seedlings affected by cadmium. J. Environ. Qual. 1997, 6, 201–205.

- Kasim, W.A. Physiological consequences of structural and ultrastructural changes induced by Zn stress in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Growth and photosynthetic apparatus. Int. J. Bot. 2007, 3, 15–22.

- De Silva, N.D.G.; Cholewa, E.; Ryser, P. Effects of combined drought and heavy metal stresses on xylem structure and hy-draulic conductivity in red maple (Acer rubrum L.). J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 5957–5966.

- Rezvani, M.; Zaefarian, F.; Miransari, M.; Nematzadeh, G.A. Uptake and translocation of cadmium and nutrients by Aeluro-pus littoralis. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2011, 58, 1413–1425.

- Uzal, O.; Yasar, F. Effects of GA3 hormone treatments on ion uptake of pepper plants under cadmium stress. Appl. Ecol. En-viron. Res. 2017, 15, 1347–1357.

- Bankaji, I.; Caçador, I.; and Sleimi, N. Physiological and biochemical response of Sueda fruticosa to cadmium and copper stress: Growth, nutrient uptake, antioxidant enzymes, phytochelatin, and glutathione levels. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 13058–13069.

- Dobrikova, A.G.; Apostolova, E.L.; Hanć, A.; Yotsova, E.; Borisova, P.; Sperdouli, I.; Adamakis, J.-D.S.; Moustakas, M. Cad-mium toxicity in Salvia sclarea L.: An integrative response of element uptake, oxidative stress markers, leaf structure and photosynthesis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 209, 111851.

- Andresen, E.; Lyubenova, L.; Hubáček, T.; Bokhari, S.N.H.; Matoušková, S.; Mijovilovich, A.; Jan Rohovec, J.; Küpper, H. Chronic exposure of soybean plants to nanomolar cadmium reveals specific additional high-affinity targets of cadmium tox-icity. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 1628–1644.

- Sharma, S.; Singh, A.K.; Tiwari, M.K.; Uttam, K.N. Prompt Screening of the Alterations in Biochemical and Mineral Profile of Wheat Plants Treated with Chromium Using Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and X-ray Fluorescence Excited by Synchrotron Radiation. Ann. Lett. 2020, 53, 482–508.

- Doostikhah, N.; Panahpoor, E.; Nadian, H.; Gholam, A. Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) nutrient and lead uptake affect-ed by zeolite and DTPA in a lead polluted soil. Plant Biol. 2019, 22, 317–322.

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Sidhu, G.R.S.; Bali, A.S.; Handa, N.; Kapoor, D.; Yadav, P.; Khan-na, K.; et al. Photosynthetic response of plants under different abiotic stresses: A review. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 509–531.

- Sarangthem, J.; Jain, M.; Gadre, R. Inhibition of δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase activity by cadmium in excised etiolated maize leaf segments during greening. Plant Soil Environ. 2011, 57, 332–337.

- Skrebsky, E.C.; Tabaldi, L.A.; Pereira, L.B.; Rauber, R.; Maldaner, J.; Cargnelutti, D.; Gonçalves, J.F.; Castro, G.Y.; Shetinger, M.R.; Nicoloso, F.T. Effect of cadmium on growth, micronutrient concentration, and δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase and acid phosphatase activities in plants of Pfaffia glomerata. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 20, 285–294.

- Gonçalves, J.; Nicoloso, F.; Becker, A.; Pereira, L.; Tabaldi, L.; Cargnelutti, D.; Pelegrin, C.; Dressler, V.; Rocha, J.; Schetinger, M. Photosynthetic pigments content, δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase and acid phosphatase activities and mineral nutri-ents concentration in cadmium-exposed Cucumis sativus L. Biologia 2209, 64, 310–318.

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Quan, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X. Response of photosynthesis to different concentrations of heavy metals in Davidia involucrata. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228563.

- Garg, P.; Chandra, P.; Devi, S. Chromium (VI) induced morphological changes in Limnanthemum cristatum Griseb: A possible bioindicator. Phytomorphology 1994, 44, 201–206.

- Gratăo, P.L.; Monteiro, C.C.; Rossi, M.L.; Martinelli, A.P.; Peres, L.E.; Medici, L.O.; Lea, P.J.; Azevedo, R.A. Differential ultra-structural changes in tomato hormonal mutants exposed to cadmium. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 67, 387–394.

- Najeeb, U.; Jilani, G.; Ali, S.; Sarwar, M.; Xu, L.; Zhou, W. (2011) Insights into cadmium induced physiological and ul-tra-structural disorders in Juncus effusus L. and its remediation through exogenous citric acid. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 565–574.

- Santos, C.L.V.; Purrut, B.; de Oliveira, J.M.P.F. The use of comet assay in plant toxicology: Recent advacnes. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 216.

- Rucińska, R.; Sobkowiak, R.; and Gwóźdź, A.E. Genotoxicity of lead in lupin root cells as evaluated by the comet assay. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2004, 9, 519–528.

- Batir, M.B.; Candan, F.; Bűtűk, Ï. Determination of the DNA changes in the artichoke seedlings (Cynara scolymus L.) subjected to lead and copper stresses. Plant Soil Environ. 2016, 3, 143–149.

- Malar, S.; Sahi, S.V.; Favas, P.J.C.; Venkatachalam, P. Assessment of mercury heavy metal toxicity-induced physiochemical and molecular changes in Sesbania grandiflora L. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 12, 3273–3282.

- Ozyigit, I.I.; Dogan, I.; Igdelioglu, S.; Filiz, E.; Karadeniz, S.; Uzunova, Z. Screening of damage induced by lead (Pb) in rye (Secale cereale L.)—A genetic and physiological approach. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2016, 30, 489–496.

- Erturk, F.A.; Agar, G.; Arslan, E.; Nardemir, G. Analysis of genetic and epigentic effects of maize seeds in response to heavy metal (Zn) stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 10291–10297.

- Pizzaia, D.; Nogueira, M.L.; Mondin, M.; Carvalho, M.E.A.; Piotto, F.A.; Rosario, M.F.; Azevedo, R.A. Cadmium toxicity and its relationship with disturbances in the cytoskeleton, cell cycle and chromosome stability. Ecotoxicology 2019, 28, 1046–1055.

- Fargašová, A. Plants as models as models for chromium and nickel risk assessment. Ecotoxicology 2012, 21, 1476–1483.

- Liu, D.; Xue, P.; Meng, Q.; Zou, J.; Gu, J.; Jiang, W. Pb/Cd effects on the organization of microtubule cytoskeleton in inter-phase and mitotic cells of Allium sativum L. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28, 695–702.

- Gzyl, J.; Chmielowska-Bąk, J.; Przymusiński, R. Gamma-tubulin distribution and ultrastructural changes in root cells of soy-bean (Glycine max L.) seedlings under cadmium stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 143, 82–90.

- Gzyl, J.; Chmielowska-Bąk, J.; Przymusiński, R.; Gwóźdź, E.A. Cadmium affects microtubule organization and post-translational modifications of tubulin in seedlings of soybean (Glycine max L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 937.

- Kranner, I.; Colville, L. Metals and seeds: Biochemical and molecular implications and their significance for seed germination. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 72, 93–105.

- Abbas, A.M.; Hammad, S.; Soliman, W.S. Influence of copper and lead on germination of three Mimosoideae plant species. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2017, 5, 320–327.

- Chmielowska-Bąk, J.; Holubek, R.; Frontasyeva, M.; Zinicovscaia, I.; Îşidoǧru, S.; Deckert, J. Tough Sprouting—Impact of Cadmium on Physiological State and Germination Rate of Soybean Seeds. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2020, 89, 8923.

- Drost, W.; Matzke, M.; Backhaus, T. Heavy metal toxicity in Lemna minor: Studies on the time dependence of growth inhibi-tion and recovery after exposure. Chemosphere 2007, 67, 36–43.