Prostate cancer is an androgen-driven tumor. Different prostate cancer therapies consequently focus on blocking the androgen receptor pathway. Clinical studies reported tumor resistance mechanisms by reactivating and bypassing the androgen pathway. Preclinical models allowed the identification, confirmation, and thorough study of these pathways.

- preclinical models

- androgen receptor

- prostate cancer

- hormone treatment

- ARSI

- ARTA

- treatment resistance

1. Introduction

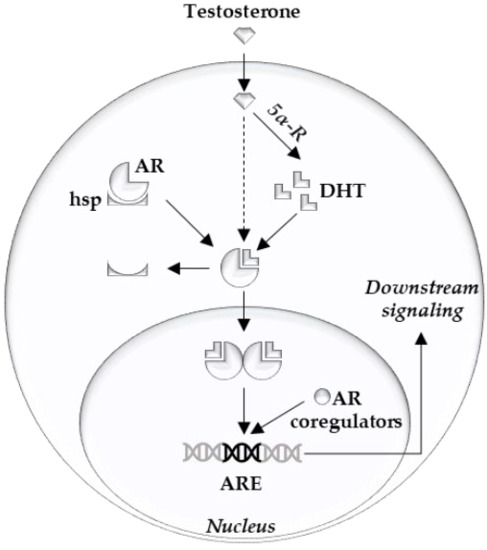

The androgen receptor (AR) is the main driver of proliferation in prostate cancer (PCa) cells, and thus is an important therapeutic target [1][2]. It consists of three structural components: the C terminal domain/ligand binding domain, the DNA binding domain, and the N terminal domain [3]. Ligand binding, dimerization, and complex formation with coregulators contribute to the downstream AR signaling [4] (Figure 1). At the cellular level, prostate epithelial cells depend on survival- and growth-inducing signals from the AR. Thus, AR inhibition deprives PCa cells of these signals and leads to G1 arrest [5].

Figure 1.

Clinical targeting of the AR is achieved by LHRH agonists/antagonists and abiraterone or by blocking the AR ligand binding pocket with anti-androgens (e.g., apalutamide, darolutamide, and enzalutamide). Unfortunately, curative treatment of advanced PCa by these AR signaling inhibitors is prevented by the occurrence of resistance mechanisms [1][2].

To become resistant against these therapies, PCa cells have to overcome the lack of growth signals. The mechanisms can be broadly categorized into two groups: (1) mechanisms that reactivate AR signaling output (i.e., AR overexpression, mutation and splice variants, glucocorticoid receptor takeover, androgen synthesis); and (2) mechanisms that bypass the AR by providing growth signals via other means (i.e., alterations in cell cycle regulators, DNA repair pathways, PI3K/PTEN alterations, trans-differentiation into AR independent phenotypes such as neuroendocrine cells).

2. Overview of Preclinical PCa Models

2.1. Prostate Cancer Derived Cell Lines

2.1.1. Cell Lines

Different cell types are used as preclinical PCa models, each with their distinct features. The most commonly used PCa cell lines and their characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview commonly used prostate cancer cell lines. Wild type (WT); androgen receptor (AR). Adapted from [6][7][8].

| Cell Line | AR/PSA | Hormone Resistant/Sensitive | Direct/Xenograft (Indirect) | Specific Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| LNCaP | + | Sensitive | Direct | T877A AR mutant, PTEN -, androgen dependent |

| LAPC-4 | + | Sensitive | Xenograft | P53 mutant, WT PTEN |

| Bone metastasis | ||||

| VCaP | + | Sensitive | Xenograft | Amplified WT AR, AR splice variants, TMPRSS-ERG fusion |

| MDA PCa 2a/b | + | Sensitive | Direct | AR mutants L702H and T878A |

| PC3 | − | Resistant | Direct | |

| CWR22(Rv1) | + | Resistant | Xenograft | H875Y AR mutant, AR splice variants, WT PTEN, Zinc Finger Duplication |

| Organ metastasis | ||||

| DU-145 (brain) | − | Resistant | Direct | |

| DuCaP (dura) | + | Sensitive | Xenograft | Amplified WT AR |

LNCaP is a cell line derived from a lymph node metastasis. It harbors a T877A AR mutation, with ligand promiscuity and has only a modest potential to form xenografts in nude mice [9]. It has multiple derivative cell lines, differing from the maternal LNCaP cell lines on different points: C4-2b (PSA +, bone metastatic in mice), LNCaP-abl (androgen-resistant, androgen depleted medium), LNCaP-AR (androgen-resistant, tissue culture), ResA and B (androgen- and anti-androgen-resistant) [10][11]. VCaP cells come from a metastatic lesion and have a wild-type, yet amplified, AR. VCaP cells are especially interesting in preclinical research as they express the TMPRSS2-ERG gene arrangement, commonly seen in PCa patients [12]. DuCaP is derived from a hormone refractory xenograft of a dura mater metastasis and is expressing PSA and overexpressing wildtype AR [7][13]. Multiple LAPC cell lines are androgen-responsive and developed from a xenograft of a PCa lymph node (LAPC-4) and bone (LAPC-9) metastasis. LAPC-4 is characterized by mutations of p53 and wildtype PTEN [14]. DU-145 are derived from a PCa brain metastasis. It does not express AR and is therefore hormone-insensitive [15]. PC3 cells are grown from a PCa bone metastasis and are, similarly to DU-145, AR negative. [16]. Some studies suggested PC3 cells to have neuroendocrine features reflecting small cell PCa and stem-like features [17][18]. 22Rv1 is a cell line derived from a relapsing xenograft of the CWR22 cell line in mice that were castrated [19]. Its AR is mutated (H874Y), while expressing a truncated AR in parallel because of an intragenic duplication of exon 3 and has a wildtype PTEN. It is mostly used in research involving splice variants of the AR [8]. MDA PCa 2A is a cell line derived from bone metastasis, being AR positive, harboring AR mutants L702H and T878A [6][20].

The big advantages of these cell lines are their relative simplicity and ease of culturing in different conditions. This enables the rapid validations of hypotheses and the simultaneous testing of multiple compounds. Also beneficial is the high amount of data that are already available on them (i.e., on DepMap and CCLE) [21][22]. Each cell line should, however, be considered as a proxy of a very specific type of PCa (i.e., AR/PSA positive, TMPRSS2-ERG fusion positive, PTEN status) (Table 3).

For example, in Tran et all., they used LNCaP cells with increased expression of wild type AR and VCaP cells. In these cells, together with the derived xenograft model, the AR inhibitor MDV3100 was identified, which was later renamed to enzalutamide [23]. PCa cell lines play an important role in investigating the plethora of AR resistance mechanisms. Such resistance to AR signaling inhibitors may pre-exist in the patient (de novo resistance) or may develop upon treatment of the patient (acquired resistance). Both types of resistance can be recapitulated in culture conditions, which enables researchers to study them in detail.

De novo resistance mechanisms can be studied in cellular models generated via genetically modifying PCa cells (i.e., stable transfections, up/down-regulation of a gene by siRNA or CRISPR/Cas9), but this largely limits their use in validation studies. In contrast to de novo resistance studies, cell lines with acquired resistance may lead to the discovery of novel resistance mechanisms, but it is challenging to identify the underlying mechanism [11]. More recently, genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screenings allowed the discovery of novel resistance mechanisms [24]. While these cell lines certainly have their place in the preclinical research landscape, they do not reflect all aspects of the heterogeneous primary tumor biology. This makes investigating, for example, the role of tumor microenvironment difficult, as only one cell type is present in the cultures. Another shortcoming is that cell lines all have severe aneuploidy. For example, the complex chromosomes of LNCaP (87 chromosomes), PC3 (58/113), and DU145 (62 chromosomes) have structural alterations of multiple chromosomes (1, 2, 4, 6, 10, 15, and 16) [25].

2.1.2. Xenografts and 3D models

Mouse xenografts are commonly created by transplanting human cell lines in mice. This can be performed in different locations: subrenal (under the renal capsule), orthotopic (in the mouse prostate), and subcutaneous (under the skin), each with its specific characteristics [8]. Creating these xenografts allows the analysis of metastasis and treatment response in an in vivo setting (Table 3).

For example, in Nguyen et al., multiple PDX were developed, reflecting prostate cancer features such as AR amplification, PTEN deletion, TP53 deletion/mutation, RB1 loss, TMPRSS2-ERG rearrangements, SPOP mutation, MSH2/MSH6 genomic aberrations, and BRCA2 loss [26]. From these models, Lam et al. selected the enzalutamide-resistant models to study supraphysiological testosterone treatment as a resensitization strategy for AR-targeted therapies [27].

Three-dimensional cell cultures can similarly be valuable in creating a basis to investigate cell–cell interactions. Cell lines can consequently be studied in a tumor microenvironment [8][28]. This can be made from artificial or biologic materials. The effects of the artificially engineered 3D scaffolds on the cells and their androgen sensitivity remain under investigation [28][29].

For example, in the spheroids of Eder et al., cancer-associated fibroblasts were co-cultured with LNCaP, LAPC4, and DuCaP. This made DuCaP resistant to enzalutamide, by increasing the Akt PI3K pathway (see further). Novel treatments can be proposed and tested in these resistant tumors [30].

2.2. Genetically-Engineered Mouse Models (GEMM)

Table 2.

[32]

| GEMM | PCa Inducement |

Specific Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Localized PCa alterations | ||

| TMPRSS-ERG fusion | + − | |

[36]

2.3. Patient-Derived Models

[28]

Table 3.

| Model | Advantages/Disadvantages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PCa cell line experiments | + Easy to culture, high-throughput system | |||

| Modest phenotype on its own, additive effect with PTEN loss | |||||

| − Very homogeneous, not reflective of clinical tumors | SPOP mutation | ||||

|

Genetically modified PCa cell lines | + Easy validation of de novo resistance mechanisms and alterations from databases − Acquired resistance more difficult to study |

+ − | Modest phenotype on its own, additive effect with PTEN loss | |

|

3D cell cultures/organoids | + Study of Cell-Cell interaction |

Advanced PCa alterations | ||

| PTEN loss | + | Most frequent GEMM, Clinical stage ranges between models. Additive effects with other alterations | |||

| Tumor surpressor genes losses (RB/p53) | + − | Modest phenotype on its own, additive effect with PTEN/BRCA mutations/RB/p53 losses | |||

| DNA repair genes mutation | + | Fewer models available, study of PARP inhibitors. Additive effects with PTEN/RB/p53 losses | |||

| Oncogenes | + | Clinical stage ranges between Myc levels, additive effects with p53, and PTEN models | |||

| Other models—mechanistic studies of targets | |||||

[33]

| − Scaffold material can alter cellular processes |

| ||

| Mouse Xenografts of PCa | + Study of metastasis and treatment response in vivo | + Working endocrine system − Limitations similar to injected cell lines |

|

Genetically modified mouse models | + In vivo validation of genetic alterations and underlying pathways − Inter species differences, questionable generalizability to human prostate cancers |

|

Patient derived cell lines | + Good correlation with specific human tumor + Reproducibility of experiments, high throughput − Only representing a certain tumor type, no cell-cell interaction |

|

Patient derived tissue cultures | + Excellent representation of respective type of prostate cancer − Limited life span, cannot be propagated |

|

Patient derived 3D cell cultures/organoids | + Study of Cell-Cell interaction in specific tumor subtypes + Medium to High throughput − Scaffold material can alter cellular processes − Technically challenging |

|

Patient derived Xenografts | + Study of metastasis and treatment of a certain tumor in vivo + Working endocrine system − No immune system, overgrowing murine tissue, tissue collection only at endpoint. |

[28]

[37]

[38]

[28]

2.4. The Ideal Preclinical Models

An ideal model for this setting would start from a heterogeneous untreated cell population of PCa. Models with a high throughput and methodologic flexibility are preferred to allow the study of different settings and interventions (Table 3). The available models are mostly derived from pre-treated metastatic patients. It is therefore challenging to find ideal preclinical models that faithfully reflect resistance to AR-targeted therapies. Most preclinical models are therefore only suitable to answer specific scientific questions. The lack of representative preclinical models undoubtedly explains the high failure rates of clinical trials with novel treatments [28].

References

- Sehgal, P.D.; Bauman, T.M.; Nicholson, T.M.; Vellky, J.E.; Ricke, E.A.; Tang, W.; Xu, W.; Huang, W.; Ricke, W.A. Tissue-specific quantification and localization of androgen and estrogen receptors in prostate cancer. Hum. Pathol. 2019, 89, 99–108.

- EAU Guidelines. Edn. Presented at the EAU Annual Congress Amsterdam 2020. Available online: (accessed on 25 December 2020).

- Tan, M.H.; Li, J.; Xu, H.E.; Melcher, K.; Yong, E.L. Androgen receptor: Structure, role in prostate cancer and drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 3–23.

- Yu, X.; Yi, P.; Hamilton, R.A.; Shen, H.; Chen, M.; Foulds, C.E.; Mancini, M.A.; Ludtke, S.J.; Wang, Z.; O'Malley, B.W. Structural Insights of Transcriptionally Active, Full-Length Androgen Receptor Coactivator Complexes. Mol. Cell 2020, 79, 812–823.e4.

- Knudsen, K.E.; Arden, K.C.; Cavenee, W.K. Multiple G1 regulatory elements control the androgen-dependent proliferation of prostatic carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 20213–20222.

- Watson, P.A.; Arora, V.K.; Sawyers, C.L. Emerging mechanisms of resistance to androgen receptor inhibitors in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 701–711.

- Hoefer, J.; Akbor, M.; Handle, F.; Ofer, P.; Puhr, M.; Parson, W.; Culig, Z.; Klocker, H.; Heidegger, I. Critical role of androgen receptor level in prostate cancer cell resistance to new generation antiandrogen enzalutamide. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 59781–59794.

- Cunningham, D.; You, Z. In vitro and in vivo model systems used in prostate cancer research. J. Biol. Methods 2015, 2.

- Horoszewicz, J.S.; Leong, S.S.; Chu, T.M.; Wajsman, Z.L.; Friedman, M.; Papsidero, L.; Kim, U.; Chai, L.S.; Kakati, S.; Arya, S.K.; et al. The LNCaP cell line—A new model for studies on human prostatic carcinoma. Prog Clin. Biol. Res. 1980, 37, 115–132.

- Thalmann, G.N.; Anezinis, P.E.; Chang, S.M.; Zhau, H.E.; Kim, E.E.; Hopwood, V.L.; Pathak, S.; von Eschenbach, A.C.; Chung, L.W. Androgen-independent cancer progression and bone metastasis in the LNCaP model of human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 2577–2581.

- Handle, F.; Prekovic, S.; Helsen, C.; Van den Broeck, T.; Smeets, E.; Moris, L.; Eerlings, R.; Kharraz, S.E.; Urbanucci, A.; Mills, I.G.; et al. Drivers of AR indifferent anti-androgen resistance in prostate cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13786.

- Korenchuk, S.; Lehr, J.E.; MClean, L.; Lee, Y.G.; Whitney, S.; Vessella, R.; Lin, D.L.; Pienta, K.J. VCaP, a cell-based model system of human prostate cancer. In Vivo 2001, 15, 163–168.

- Lee, Y.G.; Korenchuk, S.; Lehr, J.; Whitney, S.; Vessela, R.; Pienta, K.J. Establishment and characterization of a new human prostatic cancer cell line: DuCaP. In Vivo 2001, 15, 157–162.

- Klein, K.A.; Reiter, R.E.; Redula, J.; Moradi, H.; Zhu, X.L.; Brothman, A.R.; Lamb, D.J.; Marcelli, M.; Belldegrun, A.; Witte, O.N.; et al. Progression of metastatic human prostate cancer to androgen independence in immunodeficient SCID mice. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 402–408.

- Stone, K.R.; Mickey, D.D.; Wunderli, H.; Mickey, G.H.; Paulson, D.F. Isolation of a human prostate carcinoma cell line (DU 145). Int. J. Cancer 1978, 21, 274–281.

- Kaighn, M.E.; Narayan, K.S.; Ohnuki, Y.; Lechner, J.F.; Jones, L.W. Establishment and characterization of a human prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC-3). Investig. Urol. 1979, 17, 16–23.

- Sheng, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, D.L.; Li, W.B.; Luo, Z.; Chen, K.H.; Cao, J.J.; Yu, C.; Liu, W.J. Isolation and enrichment of PC-3 prostate cancer stem-like cells using MACS and serum-free medium. Oncol. Lett. 2013, 5, 787–792.

- Tai, S.; Sun, Y.; Squires, J.M.; Zhang, H.; Oh, W.K.; Liang, C.Z.; Huang, J. PC3 is a cell line characteristic of prostatic small cell carcinoma. Prostate 2011, 71, 1668–1679.

- Sramkoski, R.M.; Pretlow, T.G., 2nd; Giaconia, J.M.; Pretlow, T.P.; Schwartz, S.; Sy, M.S.; Marengo, S.R.; Rhim, J.S.; Zhang, D.; Jacobberger, J.W. A new human prostate carcinoma cell line, 22Rv1. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 1999, 35, 403–409.

- Navone, N.M.; Olive, M.; Ozen, M.; Davis, R.; Troncoso, P.; Tu, S.M.; Johnston, D.; Pollack, A.; Pathak, S.; von Eschenbach, A.C.; et al. Establishment of two human prostate cancer cell lines derived from a single bone metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 1997, 3, 2493–2500.

- Dependency Map (DepMap). Available online: (accessed on 25 December 2020).

- Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Available online: (accessed on 25 December 2020).

- Tran, C.; Ouk, S.; Clegg, N.J.; Chen, Y.; Watson, P.A.; Arora, V.; Wongvipat, J.; Smith-Jones, P.M.; Yoo, D.; Kwon, A.; et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science 2009, 324, 787–790.

- Tang, S.; Metaferia, N.Y.; Nogueira, M.F.; Gelbard, M.K.; Abou Alaiwi, S.; Seo, J.-H.; Hwang, J.H.; Strathdee, C.A.; Baca, S.C.; Li, J.; et al. A genome-scale CRISPR screen reveals PRMT1 as a critical regulator of androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer. BioRxiv 2020.

- Pan, Y.; Kytola, S.; Farnebo, F.; Wang, N.; Lui, W.O.; Nupponen, N.; Isola, J.; Visakorpi, T.; Bergerheim, U.S.; Larsson, C. Characterization of chromosomal abnormalities in prostate cancer cell lines by spectral karyotyping. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1999, 87, 225–232.

- Nguyen, H.M.; Vessella, R.L.; Morrissey, C.; Brown, L.G.; Coleman, I.M.; Higano, C.S.; Mostaghel, E.A.; Zhang, X.; True, L.D.; Lam, H.M.; et al. LuCaP Prostate Cancer Patient-Derived Xenografts Reflect the Molecular Heterogeneity of Advanced Disease and Serve as Models for Evaluating Cancer Therapeutics. Prostate 2017, 77, 654–671.

- Lam, H.M.; Nguyen, H.M.; Labrecque, M.P.; Brown, L.G.; Coleman, I.M.; Gulati, R.; Lakely, B.; Sondheim, D.; Chatterjee, P.; Marck, B.T.; et al. Durable Response of Enzalutamide-resistant Prostate Cancer to Supraphysiological Testosterone Is Associated with a Multifaceted Growth Suppression and Impaired DNA Damage Response Transcriptomic Program in Patient-derived Xenografts. Eur. Urol. 2020, 77, 144–155.

- Risbridger, G.P.; Toivanen, R.; Taylor, R.A. Preclinical Models of Prostate Cancer: Patient-Derived Xenografts, Organoids, and Other Explant Models. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a030536.

- Neuwirt, H.; Bouchal, J.; Kharaishvili, G.; Ploner, C.; Johrer, K.; Pitterl, F.; Weber, A.; Klocker, H.; Eder, I.E. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote prostate tumor growth and progression through upregulation of cholesterol and steroid biosynthesis. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 11.

- Eder, T.; Weber, A.; Neuwirt, H.; Grunbacher, G.; Ploner, C.; Klocker, H.; Sampson, N.; Eder, I.E. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Modify the Response of Prostate Cancer Cells to Androgen and Anti-Androgens in Three-Dimensional Spheroid Culture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1458.

- Shen, M.M.; Abate-Shen, C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: New prospects for old challenges. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1967–2000.

- Arriaga, J.M.; Abate-Shen, C. Genetically Engineered Mouse Models of Prostate Cancer in the Postgenomic Era. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2019, 9, a030528.

- Arriaga, J.M.; Panja, S.; Alshalalfa, M.; Zhao, J.; Zou, M.; Giacobbe, A.; Madubata, C.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Rodriguez, A.; Coleman, I.; et al. A MYC and RAS co-activation signature in localized prostate cancer drives bone metastasis and castration resistance. Nat. Cancer 2020, 1, 1082–1096.

- El Kharraz, S.; Christine, H.; Vanessa, D.; Florian, H.; Claude, L.; Martin, V.R.; Adriaan, H.; Claes, O.; Matti, P.; Nina, A.; et al. Dimerization of the ligand-binding domain is crucial for proper functioning of the androgen receptor. Endocr. Abstr. 2020.

- Kerkhofs, S.; Denayer, S.; Haelens, A.; Claessens, F. Androgen receptor knockout and knock-in mouse models. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009, 42, 11–17.

- Greenberg, N.M.; DeMayo, F.; Finegold, M.J.; Medina, D.; Tilley, W.D.; Aspinall, J.O.; Cunha, G.R.; Donjacour, A.A.; Matusik, R.J.; Rosen, J.M. Prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 3439–3443.

- Jaeschke, A.; Jacobi, A.; Lawrence, M.G.; Risbridger, G.P.; Frydenberg, M.; Williams, E.D.; Vela, I.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Bray, L.J.; Taubenberger, A. Cancer-associated fibroblasts of the prostate promote a compliant and more invasive phenotype in benign prostate epithelial cells. Mater. Today Bio 2020, 8, 100073.

- Gao, D.; Vela, I.; Sboner, A.; Iaquinta, P.J.; Karthaus, W.R.; Gopalan, A.; Dowling, C.; Wanjala, J.N.; Undvall, E.A.; Arora, V.K.; et al. Organoid cultures derived from patients with advanced prostate cancer. Cell 2014, 159, 176–187.

- Puca, L.; Bareja, R.; Prandi, D.; Shaw, R.; Benelli, M.; Karthaus, W.R.; Hess, J.; Sigouros, M.; Donoghue, A.; Kossai, M.; et al. Patient derived organoids to model rare prostate cancer phenotypes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2404.

- Song, H.; Weinstein, H.N.W.; Allegakoen, P.; Wadsworth, M.H.; Xie, J.; Yang, H.; Feng, F.Y.; Carroll, P.R.; Wang, B.; Cooperberg, M.R.; et al. Single-cell analysis of human primary prostate cancer reveals the heterogeneity of tumor-associated epithelial cell states. BioRxiv 2020.

- Centenera, M.M.; Hickey, T.E.; Jindal, S.; Ryan, N.K.; Ravindranathan, P.; Mohammed, H.; Robinson, J.L.; Schiewer, M.J.; Ma, S.; Kapur, P.; et al. A patient-derived explant (PDE) model of hormone-dependent cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2018, 12, 1608–1622.

- Handle, F.; Puhr, M.; Schaefer, G.; Lorito, N.; Hoefer, J.; Gruber, M.; Guggenberger, F.; Santer, F.R.; Marques, R.B.; van Weerden, W.M.; et al. The STAT3 Inhibitor Galiellalactone Reduces IL6-Mediated AR Activity in Benign and Malignant Prostate Models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 2722–2731.