Muscular Dystrophies (MDs) are a group of rare inherited genetic muscular pathologies encompassing a variety of clinical phenotypes, gene mutations and mechanisms of disease. MDs undergo progressive skeletal muscle degeneration causing severe health problems that lead to poor life quality, disability and premature death. There are no available therapies to counteract the causes of these diseases and conventional treatments are administered only to mitigate symptoms. Recent understanding on the pathogenetic mechanisms allowed the development of novel therapeutic strategies based on gene therapy, genome editing CRISPR/Cas9 and drug repurposing approaches. Despite the therapeutic potential of these treatments, once the actives are administered, their instability, susceptibility to degradation and toxicity limit their applications.

- nanoparticles

- Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

- myotonic dystrophy

- antisense oligonucleotides

- small molecules

- CRISPR/Cas9

1. Introduction

Muscular dystrophies (MDs) are a group of chronic inherited genetic diseases, with a worldwide estimated prevalence of 19.8–25.1 per 100,000 persons [1][2]. These multi-organ diseases mainly affect muscles, especially skeletal muscles, which undergo a progressive degeneration causing severe health problems that lead to poor life quality, loss of independence, disability and premature death [3][4]. Among the various types of MDs described so far, the most commons are the Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) and Myotonic Dystrophies (DMs) [2][3][5].

Over the last several years, drug delivery nanosystems, referred to as nanomedicine, have been extensively explored for the development of more effective and safer treatments with main applications in cancers [6][7][8][9], central nervous system-related disorders [10][11][12] and immune diseases [13][14][15]. More recently, nanomedicine has also been investigated for the treatment of viral infections [16] such as the lately approved Moderna’s and Pfizer’s Covid-19 nanoparticle-based vaccines [17][18][19][20]. In cancer therapy, nanomedicine holds potential to improve current treatments by reducing side effects of chemotherapeutic agents. Moreover, combination approaches and immunomodulation strategies have been successfully developed to boost their performances [21][22][23]. Nevertheless, only 15 nanoparticle-based cancer therapies have received clinical approval and entered the market, such as the recent liposomal Onivyde® and Vyxeos® formulations [24][25].

Currently, novel nanomedicines are optimized for the treatment of skeletal muscle pathologies like MDs. However, multiple biological and pharmaceutical barriers challenge nanomedicine delivery to skeletal muscles. Biological barriers are embodied by the complex architecture of the skeletal muscle, which encompasses the skeletal muscle parenchyma itself, connective tissue, blood vessels and nerves. One of the main hurdles for delivery to skeletal muscles lies in the presence of the dense extracellular matrix (ECM), which accounts for 1 to 10% of the muscle mass [26][27][28]. Mostly made of fibrous-forming proteins (collagens, glycoproteins, proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans) it hampers nanoparticles (NPs) penetration by retaining them in the ECM via electrostatic and mechanical interactions [29][30].

2. New Treatments based on Nanocarriers as Alternative Strategies to Facilitate Skeletal Muscle Targeting

Over the last years, the application of nanomedicine as a promising innovative approach to treat different pathologies such as MDs has been investigated. The architectural and structural complexities of skeletal muscles challenge nanomedicine delivery, especially due to the important presence of ECM [28][31]. To restrict interactions with ECM, administration of NPs by I.V. appears as a potential strategy for targeting skeletal muscle. The dense blood capillary network of skeletal muscles increases NPs access to muscle fibres [32][33]. However, once in the blood circulation, NPs can be rapidly cleared through the mononuclear phagocyte system via opsonisation or complexation with plasma proteins [34][35][36][37]. Physical and chemical instability [38][39], immunogenicity [40][41] or premature degradation [42] are other limiting factors that might interfere with NPs delivery.

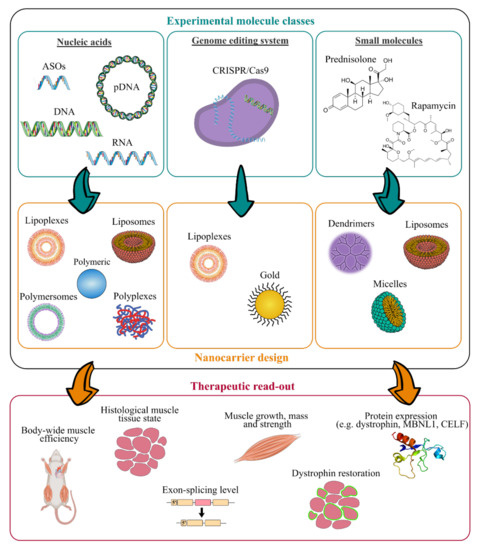

In addition, long-term administration is required to cure chronic disorders such as MDs, which makes biocompatibility and biodegradability of the nanosystems important requirements [43]. NPs should persist long enough to reverse muscle damages without involving any additional muscle degeneration, before undergoing gradual degradation [44][45]. Therefore, their design has to be optimised to associate or encapsulate active compounds and to deliver them to skeletal muscles. As illustrated in Figure 31, various NPs structures have been described [46]. RNA- and DNA-based nanocarriers are obtained via electrostatic and hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions with polymers or lipids [47][48][49]. In the case of delivery of the small molecules, their chemical properties, such as their molecular size, structure and n-octanol-water partition coefficient have an impact on the selection criteria for nanocarrier strategy [50][51]. Interestingly, synthetic nanocarriers interacting by electrostatic and hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions have been demonstrated to deliver complex CRISPR/Cas9 systems under various forms such as DNA, mRNA or ribonucleoproteins [52][53][54].

Work flow for the design of innovative nanomedicine and therapeutic readout. (ASOs, antisense oligonucleotides; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats).

As illustrated in Figure 31, many experimental molecules and macromolecules have been selected as candidates for MD therapies, and a wide range of nanocarriers has allowed their delivery to skeletal muscles, promoting in most of the cases their therapeutic potential.

The present section aims at highlighting nanosystems used for DMD and DM applications that reached preclinical studies. An overview of the various described nanosystems is reported in Table 21.

Table 21. Recapitulative table of the diverse described nanosystems tested in vivo for treating MDs (PEI, polyethylenimine; PEG, polyethylene glycol; PLGA, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid); PMMA, poly(methyl methacrylate); NIPAM, N-isopropylacrylamide; PEA, poly(ethylene adipate); PLys, poly(l-lysine); PPE-EA, poly(2-aminoethyl propylene phosphate); PAMAM-OH, hydroxyl-terminated poly(amidoamine); DMPC, L-a-dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine; (C12(EO)23), polyoxyethylene(23) lauryl ether; NPs, nanoparticles; ASO, antisense oligonucleotide; PMO, phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer; GA, glatiramer acetate; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; I.M., intramuscular injection; I.V., intravenous injection; I.P., intraperitoneal).

|

Class of Nanocarriers |

Nanocarrier Composition |

Muscle Pathology |

Loaded Molecules |

Therapeutic Target |

Mouse Model |

Advantages and Limitations |

Admin. Route |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Polymeric |

PEI-PEG |

DMD |

2′-OMe ASO |

Dystrophin pre-mRNA |

mdx |

(+) high dystrophin-positive fibers increased (+) long term residual efficacy over 6 weeks (-) low general transfection efficiency |

I.M. |

[55] |

|

PEI-PEG/PLGA |

DMD |

2′-OMe ASO |

Dystrophin pre-mRNA |

mdx |

(-) no improvement compared to PEI-PEG-ASO |

I.M. |

[56] | |

|

PEI-Pluronic® |

DMD |

PMO ASO |

Dystrophin pre-mRNA |

mdx |

(+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 4-fold after I.M. (+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 3-fold in all skeletal muscles after I.V. (+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 5-fold in heart after I.V. (+) low muscle tissue, liver and kidney toxicity (-) mild general transfection efficiency |

I.M./I.V. |

[57] | |

|

DMD |

2′-OMe ASO |

Dystrophin pre-mRNA |

mdx |

(+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 10-fold |

I.M. |

[58] | ||

|

PEG-polycaprolactone PEG-(polylactic acid) |

DMD |

PMO ASO |

Dystrophin pre-mRNA |

mdx |

(+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 3-fold (+) low muscle tissue toxicity (-) mild general transfection efficiency |

I.M. |

[59] | |

|

PMMA |

DMD |

2′-OMe ASO |

Dystrophin pre-mRNA |

mdx |

(+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 7-fold (-) slow biodegradability |

I.P. |

[60] | |

|

PMMA/NIPAM |

DMD |

2′-OMe ASO |

Dystrophin pre-mRNA |

mdx |

(+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 4-fold (+) body-wide dystrophin restoration after I.V. (+) exon-skipping level enhanced up to 20-fold (+) long term residual efficacy over 90 days |

I.P./I.V. |

[61][62] | |

|

PEA |

DMD |

2′-OMe ASO |

Dystrophin pre-mRNA |

mdx |

(+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 3–10-fold |

I.M. |

[63] | |

|

DMD |

PMO ASO |

Dystrophin pre-mRNA |

mdx |

(+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 3-fold after I.M. (+) body-wide dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 3-fold after I.V. |

I.M./I.V. |

[63] | ||

|

Muscle atrophy/ DMD |

pDNA |

Cell nucleus |

mdx |

(+) transfection efficiency enhanced up to 6-fold |

I.M. |

[64] | ||

|

PLys-PEG |

Muscle atrophy |

pDNA |

Cell nucleus |

Balb/c |

(+) transfection efficiency enhanced up to 10-fold |

I.V. |

[65] | |

|

PPE-EA |

Muscle atrophy |

pDNA |

Cell nucleus |

Balb/c |

(+) transfection efficiency enhanced up to 13-fold (+) long term residual efficacy over 14 days |

I.M. |

[66] | |

|

Atelocollagen |

Muscle atrophy/ DMD |

siRNA |

Cytoplasm |

mdx |

(+) higher mass muscle increase |

I.M./I.V. |

[67] | |

|

PAMAM-OH |

Muscle atrophy |

Angiotensin (1–7) |

Cytoplasm |

Balb/c |

(+) higher anti-atrophic effects |

I.P. |

[68] | |

|

Lipidic |

PEG-bubble liposomes |

DMD |

PMO ASO |

Dystrophin pre-mRNA |

mdx |

(+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 1.5-fold (+) exon-skipping level enhanced up to 5-fold |

I.M. |

[69] |

|

DM1 |

PMO ASO |

Clcn1 pre-mRNA |

HSALR |

(+) increased expression of Clcn1 protein up to 1.4-fold |

I.M. |

[70] | ||

|

Nanolipodendrosomes |

DMD |

MyoD and GA |

Cytoplasm |

SW-1 |

(+) slight mass muscle increase |

I.M. |

[71] | |

|

Nanoliposomes |

DMD |

Glucocorticoide |

Cell nucleus |

mdx |

(+) lower inflammatory induced response (+) lower bone catabolic effects |

I.V. |

[72] | |

|

Hybrid liposomes DMPC and (C12(EO)23) |

DMD |

Gentamicin |

Ribosomes |

mdx |

(+) dystrophin-positive fibers increased up to 4-fold (+) lower ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity |

I.P. |

[73] | |

|

Perfluorocarbon |

DMD |

Rapamycin |

mTORC1 complex |

mdx |

(+) high muscle strength increase (+) high cardiac contractile performance increase |

I.V. |

[74] | |

|

Lipid NPs |

DMD |

CRISPR/Cas9 |

Dystrophin DNA sequence |

ΔEx44 |

(+) dystrophin expression restored up to 5% |

I.M. |

[75] | |

|

Inorganic |

Gold |

DMD |

CRISPR/Cas9 |

Dystrophin DNA sequence |

mdx |

(+) HDR in the dystrophin gene enhanced up to 18-fold |

I.M. |

[76] |

3. Future Perspectives

The recent understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of MDs highlights the urgent need of new and more effective treatments [77][78]. Nanomedicine demonstrated to enhance the therapeutic potential of gene therapy and drug repurposing approaches. As an example, pentamidine-loaded nanomedicines were used to explore the activity of the drug, not only as an anti-leishmaniasis agent but also as an anticancer agent to reduce drug associated toxicity, such as its severe nephrotoxicity [79][80]. Ongoing investigations are aimed at demonstrating the efficacy of this novel formulation to treat DM1 (study in progress).

New therapeutic approaches needed a continuous administration throughout patient’s life, making the biocompatibility and biodegradability of delivery systems a crucial feature to preserve skeletal muscle from additional alterations. As presented in this review, the main advantages of nanosystems rely on their physico-chemical properties, namely composition, size and surface potential that can be modulated to avoid nanocarrier toxicity, and to load specific actives and deliver them in a target site.

To disclose the potential of nanomedicine application to MDs treatment, the gap between in vitro and in vivo testing has to be filled. In addition, to understand the fate of nanosystems once administered to MDs mice, biodistribution studies need to be addressed. To date, only a few investigations reported NPs biodistribution into skeletal muscles through different administration routes as I.V., I.P. and I.M. (tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles) [65][81][82]. After systemic administration, NPs spread into tissues through blood systemic circulation, then, extravasate into the ECM before reaching muscle fibres. It has been suggested that the dense blood capillary network wrapping skeletal myofibers could be favourable to NPs accumulation and distribution following I.V. injection [83]. Hydrodynamic injection is also known to facilitate gene delivery by transient enhancement of the plasma membrane’s permeability [33][84][85]. However, the applied pressure due to the hindrance of the blood flow might cause oedema and inflammation, restricting the translation of this technique to clinic [86].

Overcoming the ECM barrier remains another important goal to improve NPs distribution in skeletal muscle fibres. Surface engineered nanosystems have been designed to actively promote the interaction between nanosystems and cells [87]. The high specificity of antibodies for their corresponding antigen provides a selective and potent approach for therapeutic NPs targeting [88]. As an example, the murine monoclonal antibody (3E10), capable of binding the surface of muscle cells, has been reported to improve active targeting [89][90]. However, no scientific studies on antibody-functionalised NPs have been conducted for skeletal muscle targeting so far. More commonly used, short peptides sequences (e.g., ASSLNIA or SKTFNTHPQSTP) have proved promising as NPs functionalization for specific tissue-targeting [91][92][93]. Several examples of peptides targeting muscle cells have been reported [94][95][96] and association to nanosystems may lead to improved selectivity of NPs for skeletal muscle. Polymeric nanosystems have been functionalised with active targeting agents that preferentially bind active molecules or receptors expressed on the surface of muscle cells. Active targeting-dependent uptake has been demonstrated using PLGA nanocarriers functionalised with a muscle-homing peptide M12 [97]. Biodistribution studies revealed a preferential accumulation of targeted NPs in skeletal muscle cells in mdx mice, compared to untargeted nanocarriers, increasing the accumulation of polymeric NPs and enhancing therapeutic efficacy [82].

References

- Shieh, P.B. Muscular dystrophies and other genetic myopathies. Neurol. Clin. 2013, 31, 1009–1029.

- Theadom, A.; Rodrigues, M.; Roxburgh, R.; Balalla, S.; Higgins, C.; Bhattacharjee, R.; Jones, K.; Krishnamurthi, R.; Feigin, V. Prevalence of muscular dystrophies: A systematic literature review. Neuroepidemiology 2014, 43, 259–268.

- Mercuri, E.; Bönnemann, C.G.; Muntoni, F. Muscular dystrophies. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2019, 394, 2025–2038.

- Carter, J.C.; Sheehan, D.W.; Prochoroff, A.; Birnkrant, D.J. Muscular Dystrophies. Clin. Chest Med. 2018, 39, 377–389.

- Johnson, N.E. Myotonic Dystrophies. Continuum 2019, 25, 1682–1695.

- Pedrini, I.; Gazzano, E.; Chegaev, K.; Rolando, B.; Marengo, A.; Kopecka, J.; Fruttero, R.; Ghigo, D.; Arpicco, S.; Riganti, C. Liposomal nitrooxy-doxorubicin: One step over caelyx in drug-resistant human cancer cells. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 3068–3079.

- Autio, K.A.; Dreicer, R.; Anderson, J.; Garcia, J.A.; Alva, A.; Hart, L.L.; Milowsky, M.I.; Posadas, E.M.; Ryan, C.J.; Graf, R.P.; et al. Safety and efficacy of BIND-014, a docetaxel nanoparticle targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: A phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1344–1351.

- Van der Meel, R.; Sulheim, E.; Shi, Y.; Kiessling, F.; Mulder, W.J.M.; Lammers, T. Smart cancer nanomedicine. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1007–1017.

- Wang-Gillam, A.; Hubner, R.A.; Siveke, J.T.; Von Hoff, D.D.; Belanger, B.; de Jong, F.A.; Mirakhur, B.; Chen, L.-T. NAPOLI-1 phase 3 study of liposomal irinotecan in metastatic pancreatic cancer: Final overall survival analysis and characteristics of long-term survivors. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 108, 78–87.

- Hanif, S.; Muhammad, P.; Chesworth, R.; Rehman, F.U.; Qian, R.; Zheng, M.; Shi, B. Nanomedicine-Based Immunotherapy for Central Nervous System Disorders. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 936–953.

- You, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, T.; Guo, S.; Dong, T.; Xu, J.; Anderson, G.J.; et al. Targeted brain delivery of rabies virus glycoprotein 29-modified deferoxamine-loaded nanoparticles reverses functional deficits in Parkinsonian mice. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 4123–4139.

- Dos Santos Tramontin, N.; da Silva, S.; Arruda, R.; Ugioni, K.S.; Canteiro, P.B.; de Bem Silveira, G.; Mendes, C.; Silveira, P.C.L.; Muller, A.P. Gold nanoparticles treatment reverses brain damage in Alzheimer’s disease model. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 926–936.

- Pearson, R.M.; Podojil, J.R.; Shea, L.D.; King, N.J.C.; Miller, S.D.; Getts, D.R. Overcoming challenges in treating autoimmuntity: Development of tolerogenic immune-modifying nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2019, 18, 282–291.

- Zhao, G.; Liu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Z.-Q.; Cao, Z.-T.; Zhang, H.-B.; Xu, C.-F.; Wang, J. Nanoparticle-delivered siRNA targeting Bruton’s tyrosine kinase for rheumatoid arthritis therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 4698–4707.

- Horwitz, D.A.; Bickerton, S.; Koss, M.; Fahmy, T.M.; La Cava, A. Suppression of murine Lupus by CD4+ and CD8+ treg cells induced by T cell-targeted nanoparticles loaded with interleukin-2 and transforming growth factor β. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 632–640.

- Fries, C.N.; Curvino, E.J.; Chen, J.-L.; Permar, S.R.; Fouda, G.G.; Collier, J.H. Advances in nanomaterial vaccine strategies to address infectious diseases impacting global health. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 1–14.

- Nanomedicine and the COVID-19 vaccines. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 1.

- Sahin, U.; Muik, A.; Derhovanessian, E.; Vogler, I.; Kranz, L.M.; Vormehr, M.; Baum, A.; Pascal, K.; Quandt, J.; Maurus, D.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T cell responses. Nature 2020, 586, 594–599.

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the MRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 384, 403–416.

- Chung, Y.H.; Beiss, V.; Fiering, S.N.; Steinmetz, N.F. COVID-19 vaccine frontrunners and their nanotechnology design. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 12522–12537.

- Kranz, L.M.; Diken, M.; Haas, H.; Kreiter, S.; Loquai, C.; Reuter, K.C.; Meng, M.; Fritz, D.; Vascotto, F.; Hefesha, H.; et al. Systemic RNA delivery to dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature 2016, 534, 396–401.

- Xin, X.; Kumar, V.; Lin, F.; Kumar, V.; Bhattarai, R.; Bhatt, V.R.; Tan, C.; Mahato, R.I. Redox-responsive nanoplatform for codelivery of miR-519c and gemcitabine for pancreatic cancer therapy. Sci. Adv. 2020, eabd6764.

- Sasso, M.S.; Lollo, G.; Pitorre, M.; Solito, S.; Pinton, L.; Valpione, S.; Bastiat, G.; Mandruzzato, S.; Bronte, V.; Marigo, I.; et al. Low dose gemcitabine-loaded lipid nanocapsules target monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells and potentiate cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2016, 96, 47–62.

- Lancet, J.E.; Uy, G.L.; Cortes, J.E.; Newell, L.F.; Lin, T.L.; Ritchie, E.K.; Stuart, R.K.; Strickland, S.A.; Hogge, D.; Solomon, S.R.; et al. CPX-351 (cytarabine and daunorubicin) liposome for injection versus conventional cytarabine plus daunorubicin in older patients with newly diagnosed secondary acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2684–2692.

- Salvioni, L.; Rizzuto, M.A.; Bertolini, J.A.; Pandolfi, L.; Colombo, M.; Prosperi, D. Thirty years of cancer nanomedicine: Success, frustration, and hope. Cancers 2019, 11, 1855.

- Gillies, A.R.; Lieber, R.L. Structure and function of the skeletal muscle extracellular matrix. Muscle Nerve 2011, 44, 318–331.

- Yhee, J.Y.; Yoon, H.Y.; Kim, H.; Jeon, S.; Hergert, P.; Im, J.; Panyam, J.; Kim, K.; Nho, R.S. The effects of collagen-rich extracellular matrix on the intracellular delivery of glycol chitosan nanoparticles in human lung fibroblasts. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 6089–6105.

- Sleboda, D.A.; Stover, K.K.; Roberts, T.J. Diversity of extracellular matrix morphology in vertebrate skeletal muscle. J. Morphol. 2020, 281, 160–169.

- Engin, A.B.; Nikitovic, D.; Neagu, M.; Henrich-Noack, P.; Docea, A.O.; Shtilman, M.I.; Golokhvast, K.; Tsatsakis, A.M. Mechanistic understanding of nanoparticles’ interactions with extracellular matrix: The cell and immune system. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2017, 14, 22.

- Stylianopoulos, T.; Poh, M.Z.; Insin, N.; Bawendi, M.G.; Fukumura, D.; Munn, L.L.; Jain, R.K. Diffusion of particles in the extracellular matrix: The effect of repulsive electrostatic interactions. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 1342–1349.

- Theocharis, A.D.; Skandalis, S.S.; Gialeli, C.; Karamanos, N.K. Extracellular matrix structure. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 97, 4–27.

- Zhang, G.; Budker, V.; Williams, P.; Subbotin, V.; Wolff, J.A. Efficient expression of naked DNA delivered intraarterially to limb muscles of nonhuman primates. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001, 12, 427–438.

- Hagstrom, J.E.; Hegge, J.; Zhang, G.; Noble, M.; Budker, V.; Lewis, D.L.; Herweijer, H.; Wolff, J.A. A facile nonviral method for delivering genes and siRNAs to skeletal muscle of mammalian limbs. Mol. Ther. 2004, 10, 386–398.

- Gref, R.; Minamitake, Y.; Peracchia, M.T.; Trubetskoy, V.; Torchilin, V.; Langer, R. Biodegradable long-circulating polymeric nanospheres. Science 1994, 263, 1600–1603.

- Longmire, M.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Clearance properties of nano-sized particles and molecules as imaging agents: Considerations and caveats. Nanomedicine 2008, 3, 703–717.

- Gustafson, H.H.; Holt-Casper, D.; Grainger, D.W.; Ghandehari, H. Nanoparticle uptake: The phagocyte problem. Nano Today 2015, 10, 487–510.

- Blanco, E.; Shen, H.; Ferrari, M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 941–951.

- Nguyen, V.H.; Lee, B.-J. Protein corona: A new approach for nanomedicine design. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 3137–3151.

- Tenzer, S.; Docter, D.; Kuharev, J.; Musyanovych, A.; Fetz, V.; Hecht, R.; Schlenk, F.; Fischer, D.; Kiouptsi, K.; Reinhardt, C.; et al. Rapid formation of plasma protein corona critically affects nanoparticle pathophysiology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 772–781.

- Stano, A.; Nembrini, C.; Swartz, M.A.; Hubbell, J.A.; Simeoni, E. Nanoparticle size influences the magnitude and quality of mucosal immune responses after intranasal immunization. Vaccine 2012, 30, 7541–7546.

- Hoshyar, N.; Gray, S.; Han, H.; Bao, G. The effect of nanoparticle size on in vivo pharmacokinetics and cellular interaction. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 673–692.

- Vlasova, I.I.; Kapralov, A.A.; Michael, Z.P.; Burkert, S.C.; Shurin, M.R.; Star, A.; Shvedova, A.A.; Kagan, V.E. Enzymatic oxidative biodegradation of nanoparticles: Mechanisms, significance and applications. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2016, 299, 58–69.

- Tidball, J.G.; Welc, S.S.; Wehling-Henricks, M. Immunobiology of inherited muscular dystrophies. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 8, 1313–1356.

- Ebner, D.C.; Bialek, P.; El-Kattan, A.F.; Ambler, C.M.; Tu, M. Strategies for skeletal muscle targeting in drug discovery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 1327–1336.

- Smoak, M.M.; Mikos, A.G. Advances in biomaterials for skeletal muscle engineering and obstacles still to overcome. Mater. Today Bio 2020, 7, 100069.

- Evers, M.M.; Toonen, L.J.A.; van Roon-Mom, W.M.C. Antisense oligonucleotides in therapy for neurodegenerative disorders. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 87, 90–103.

- Kauffman, K.J.; Webber, M.J.; Anderson, D.G. Materials for non-viral intracellular delivery of messenger RNA therapeutics. J. Control. Release 2016, 240, 227–234.

- Parlea, L.; Puri, A.; Kasprzak, W.; Bindewald, E.; Zakrevsky, P.; Satterwhite, E.; Joseph, K.; Afonin, K.A.; Shapiro, B.A. Cellular delivery of RNA nanoparticles. ACS Comb. Sci. 2016, 18, 527–547.

- Wahane, A.; Waghmode, A.; Kapphahn, A.; Dhuri, K.; Gupta, A.; Bahal, R. Role of lipid-based and polymer-based non-viral vectors in nucleic acid delivery for next-generation gene therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 2866.

- Mastria, E.M.; Cai, L.Y.; Kan, M.J.; Li, X.; Schaal, J.L.; Fiering, S.; Gunn, M.D.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Nair, S.K.; Chilkoti, A. Nanoparticle formulation improves doxorubicin efficacy by enhancing host antitumor immunity. J. Control. Release 2018, 269, 364–373.

- Yu, A.-M.; Choi, Y.H.; Tu, M.-J. RNA drugs and RNA targets for small molecules: Principles, progress, and challenges. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 862–898.

- Givens, B.E.; Naguib, Y.W.; Geary, S.M.; Devor, E.J.; Salem, A.K. Nanoparticle based delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing therapeutics. AAPS J. 2018, 20, 108.

- Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Cheng, K. Delivery strategies of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing system for therapeutic applications. J. Control. Release 2017, 266, 17–26.

- Min, Y.-L.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. CRISPR correction of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Annu. Rev. Med. 2019, 27, 239–255.

- Williams, J.H.; Schray, R.C.; Sirsi, S.R.; Lutz, G.J. Nanopolymers improve delivery of exon skipping oligonucleotides and concomitant dystrophin expression in skeletal muscle of mdx mice. BMC Biotechnol. 2008, 8, 35.

- Sirsi, S.R.; Schray, R.C.; Wheatley, M.A.; Lutz, G.J. Formulation of polylactide-co-glycolic acid nanospheres for encapsulation and sustained release of poly(ethylene imine)-poly(ethylene glycol) copolymers complexed to oligonucleotides. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2009, 7, 1.

- Wang, M.; Wu, B.; Lu, P.; Cloer, C.; Tucker, J.D.; Lu, Q. Polyethylenimine-modified Pluronics (PCMs) improve morpholino oligomer delivery in cell culture and dystrophic mdx mice. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 210–216.

- Wang, M.; Wu, B.; Lu, P.; Tucker, J.D.; Milazi, S.; Shah, S.N.; Lu, Q.L. Pluronic–PEI copolymers enhance exon-skipping of 2′-O-methyl phosphorothioate oligonucleotide in cell culture and dystrophic mdx mice. Gene Ther. 2014, 21, 52–59.

- Kim, Y.; Tewari, M.; Pajerowski, J.D.; Cai, S.; Sen, S.; Williams, J.; Sirsi, S.; Lutz, G.; Discher, D.E. Polymersome delivery of siRNA and antisense oligonucleotides. J. Control. Release 2009, 134, 132–140.

- Rimessi, P.; Sabatelli, P.; Fabris, M.; Braghetta, P.; Bassi, E.; Spitali, P.; Vattemi, G.; Tomelleri, G.; Mari, L.; Perrone, D.; et al. Cationic PMMA nanoparticles bind and deliver antisense oligoribonucleotides allowing restoration of dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 820–827.

- Ferlini, A.; Sabatelli, P.; Fabris, M.; Bassi, E.; Falzarano, S.; Vattemi, G.; Perrone, D.; Gualandi, F.; Maraldi, N.M.; Merlini, L.; et al. Dystrophin restoration in skeletal, heart and skin arrector pili smooth muscle of mdx mice by ZM2 NP–AON complexes. Gene Ther. 2010, 17, 432–438.

- Bassi, E.; Falzarano, S.; Fabris, M.; Gualandi, F.; Merlini, L.; Vattemi, G.; Perrone, D.; Marchesi, E.; Sabatelli, P.; Sparnacci, K.; et al. Persistent dystrophin protein restoration 90 days after a course of intraperitoneally administered naked 2′OMePS AON and ZM2 NP-AON complexes in mdx Mice. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 1–8.

- Wang, M.; Wu, B.; Tucker, J.D.; Bollinger, L.E.; Lu, P.; Lu, Q. Poly(ester amine) composed of polyethylenimine and Pluronic enhance delivery of antisense oligonucleotides in vitro and in dystrophic mdx mice. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2016, 5, e341.

- Wang, M.; Tucker, J.D.; Lu, P.; Wu, B.; Cloer, C.; Lu, Q. Tris[2-(acryloyloxy)ethyl]isocyanurate cross-linked low-molecular-weight polyethylenimine as gene delivery carriers in cell culture and dystrophic mdx mice. Bioconjug. Chem. 2012, 23, 837–845.

- Itaka, K.; Osada, K.; Morii, K.; Kim, P.; Yun, S.-H.; Kataoka, K. Polyplex nanomicelle promotes hydrodynamic gene introduction to skeletal muscle. J. Control. Release 2010, 143, 112–119.

- Wang, J.; Zhang, P.-C.; Mao, H.-Q.; Leong, K.W. Enhanced gene expression in mouse muscle by sustained release of plasmid DNA using PPE-EA as a carrier. Gene Ther. 2002, 9, 1254–1261.

- Kinouchi, N.; Ohsawa, Y.; Ishimaru, N.; Ohuchi, H.; Sunada, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Tanimoto, Y.; Moriyama, K.; Noji, S. Atelocollagen-mediated local and systemic applications of myostatin-targeting siRNA increase skeletal muscle mass. Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 1126–1130.

- Márquez-Miranda, V.; Abrigo, J.; Rivera, J.C.; Araya-Duran, I.; Aravena, J.; Simon, F.; Pacheco, N.; Gonzalez-Nilo, F.D.; Cabello-Verrugio, C. The complex of PAMAM-OH dendrimer with angiotensin (1-7) prevented the disuse-induced skeletal muscle atrophy in mice. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 1985–1999.

- Negishi, Y.; Ishii, Y.; Shiono, H.; Akiyama, S.; Sekine, S.; Kojima, T.; Mayama, S.; Kikuchi, T.; Hamano, N.; Endo-Takahashi, Y.; et al. Bubble liposomes and ultrasound exposure improve localized morpholino oligomer delivery into the skeletal muscles of dystrophic mdx mice. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 1053–1061.

- Koebis, M.; Kiyatake, T.; Yamaura, H.; Nagano, K.; Higashihara, M.; Sonoo, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Negishi, Y.; Endo-Takahashi, Y.; Yanagihara, D.; et al. Ultrasound-enhanced delivery of morpholino with bubble liposomes ameliorates the myotonia of myotonic dystrophy model mice. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2242.

- Afzal, E.; Zakeri, S.; Keyhanvar, P.; Bagheri, M.; Mahjoubi, P.; Asadian, M.; Omoomi, N.; Dehqanian, M.; Ghalandarlaki, N.; Darvishmohammadi, T.; et al. Nanolipodendrosome-loaded glatiramer acetate and myogenic differentiation 1 as augmentation therapeutic strategy approaches in muscular dystrophy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 2943–2960.

- Turjeman, K.; Yanay, N.; Elbaz, M.; Bavli, Y.; Gross, M.; Rabie, M.; Barenholz, Y.; Nevo, Y. Liposomal steroid nano-drug is superior to steroids as-is in mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular mystrophy. Nanomedicine 2019, 16, 34–44.

- Yukihara, M.; Ito, K.; Tanoue, O.; Goto, K.; Matsushita, T.; Matsumoto, Y.; Masuda, M.; Kimura, S.; Ueoka, R. Effective drug delivery system for Duchenne muscular dystrophy using hybrid liposomes including gentamicin along with reduced toxicity. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34, 712–716.

- Bibee, K.P.; Cheng, Y.; Ching, J.K.; Marsh, J.N.; Li, A.J.; Keeling, R.M.; Connolly, A.M.; Golumbek, P.T.; Myerson, J.W.; Hu, G.; et al. Rapamycin nanoparticles target defective autophagy in muscular dystrophy to enhance both strength and cardiac function. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 2047–2061.

- Wei, T.; Cheng, Q.; Min, Y.-L.; Olson, E.N.; Siegwart, D.J. Systemic nanoparticle delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins for effective tissue specific genome editing. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3232.

- Lee, K.; Conboy, M.; Park, H.M.; Jiang, F.; Kim, H.J.; Dewitt, M.A.; Mackley, V.A.; Chang, K.; Rao, A.; Skinner, C.; et al. Nanoparticle delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein and donor DNA in vivo induces homology-directed DNA repair. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 889–901.

- Verhaart, I.E.C.; Aartsma-Rus, A. Therapeutic developments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 373–386.

- Smith, R.A.; Miller, T.M.; Yamanaka, K.; Monia, B.P.; Condon, T.P.; Hung, G.; Lobsiger, C.S.; Ward, C.M.; McAlonis-Downes, M.; Wei, H.; et al. Antisense oligonucleotide therapy for neurodegenerative disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 2290–2296.

- Carton, F.; Chevalier, Y.; Nicoletti, L.; Tarnowska, M.; Stella, B.; Arpicco, S.; Malatesta, M.; Jordheim, L.P.; Briançon, S.; Lollo, G. Rationally designed hyaluronic acid-based nano-complexes for pentamidine delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 568, 118526.

- Stella, B.; Andreana, I.; Zonari, D.; Arpicco, S. Pentamidine-loaded lipid and polymer nanocarriers as tunable anticancer drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 109, 1297–1302.

- Falzarano, M.S.; Bassi, E.; Passarelli, C.; Braghetta, P.; Ferlini, A. Biodistribution studies of polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery in mice. Hum Gene Ther. 2014, 25, 927–928.

- Huang, D.; Yue, F.; Qiu, J.; Deng, M.; Kuang, S. Polymeric nanoparticles functionalized with muscle-homing peptides for targeted delivery of phosphatase and tensin homolog inhibitor to skeletal muscle. Acta Biomater. 2020, 118, 196–206.

- Suzuki, R.; Takizawa, T.; Negishi, Y.; Hagisawa, K.; Tanaka, K.; Sawamura, K.; Utoguchi, N.; Nishioka, T.; Maruyama, K. Gene delivery by combination of novel liposomal bubbles with perfluoropropane and ultrasound. J. Control. Release 2007, 117, 130–136.

- Herweijer, H.; Wolff, J.A. Gene therapy progress and prospects: Hydrodynamic gene delivery. Gene Ther. 2007, 14, 99–107.

- Kumbhari, V.; Li, L.; Piontek, K.; Ishida, M.; Fu, R.; Khalil, B.; Garrett, C.M.; Liapi, E.; Kalloo, A.N.; Selaru, F.M. Successful liver-directed gene delivery by ERCP-guided hydrodynamic injection (with Videos). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 88, 755–763.

- Le Guen, Y.T.; Le Gall, T.; Midoux, P.; Guégan, P.; Braun, S.; Montier, T. Gene transfer to skeletal muscle using hydrodynamic limb vein injection: Current applications, hurdles and possible optimizations. J. Gene Med. 2020, 22, e3150.

- Ashfaq, U.A.; Riaz, M.; Yasmeen, E.; Yousaf, M. Recent advances in nanoparticle-based targeted drug-delivery systems against cancer and role of tumor microenvironment. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2017, 34, 317–353.

- Pietersz, G.A.; Wang, X.; Yap, M.L.; Lim, B.; Peter, K. Therapeutic targeting in nanomedicine: The future lies in recombinant antibodies. Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 1873–1889.

- Arahata, K.; Ishiura, S.; Ishiguro, T.; Tsukahara, T.; Suhara, Y.; Eguchi, C.; Ishiharat, T.; Nonaka, I.; Ozawa, E.; Sugita, H. Immunostaining of skeletal and cardiac muscle surface membrane with antibody against Duchenne muscular dystrophy peptide. Nature 1988, 333, 861–863.

- Zhang, R.; Kim, A.S.; Fox, J.M.; Nair, S.; Basore, K.; Klimstra, W.B.; Rimkunas, R.; Fong, R.H.; Lin, H.; Poddar, S.; et al. Mxra8 is a receptor for multiple arthritogenic alphaviruses. Nature 2018, 557, 570–574.

- Poon, W.; Zhang, X.; Bekah, D.; Teodoro, J.G.; Nadeau, J.L. Targeting B16 tumors in vivo with peptide-conjugated gold nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 285101.

- Yu-Wai-Man, C.; Tagalakis, A.D.; Manunta, M.D.; Hart, S.L.; Khaw, P.T. Receptor-targeted liposome-peptide-siRNA nanoparticles represent an efficient delivery system for MRTF silencing in conjunctival fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21881.

- Tajau, R.; Rohani, R.; Abdul Hamid, S.S.; Adam, Z.; Mohd Janib, S.N.; Salleh, M.Z. Surface functionalisation of poly-APO- b -polyol ester cross-linked copolymers as core–shell nanoparticles for targeted breast cancer therapy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21704.

- Yu, C.-Y.; Yuan, Z.; Cao, Z.; Wang, B.; Qiao, C.; Li, J.; Xiao, X. A muscle-targeting peptide displayed on AAV2 improves muscle tropism on systemic delivery. Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 953–962.

- Seow, Y.; Yin, H.; Wood, M.J.A. Identification of a novel muscle targeting peptide in mdx mice. Peptides 2010, 31, 1873–1877.

- Tsoumpra, M.K.; Fukumoto, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Takeda, S.; Wood, M.J.A.; Aoki, Y. Peptide-conjugate antisense based splice-correction for Duchenne muscular dystrophy and other neuromuscular diseases. EBioMedicine 2019, 45, 630–645.

- Gao, X.; Zhao, J.; Han, G.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, X.; Cao, L.; Wang, Q.; Moulton, H.M.; Yin, H. Effective dystrophin restoration by a novel muscle-homing peptide-morpholino conjugate in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 1333–1341.