The current Coronavirus disease 2019 or COVID-19 pandemic has infected over two million people and resulted in the death of over one hundred thousand people at the time of writing this review. The disease is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2). Even though multiple vaccines and treatments are under development so far, the disease is only slowing down under extreme social distancing measures that are difficult to maintain. SARS-COV2 is an enveloped virus that is surrounded by a lipid bilayer. Lipids are fundamental cell components that play various biological roles ranging from being a structural building block to a signaling molecule as well as a central energy store. The role lipids play in viral infection involves the fusion of the viral membrane to the host cell, viral replication, and viral endocytosis and exocytosis. Since lipids play a crucial function in the viral life cycle, we asked whether drugs targeting lipid metabolism, such as statins, can be utilized against SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses. In this review, we discuss the role of lipid metabolism in viral infection as well as the possibility of targeting lipid metabolism to interfere with the viral life cycle.

- Lipid metabolism, Viral Entry, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-

1. Role of Lipids in Viral Metabolism and Membrane Formation

The host lipid biogenesis pathways play crucial roles in controlling virus replication. Lipids can act as direct receptors or entry co-factors for all types of viruses at the cell surface or the endosomes [1][2]. They also play an important role in the formation and function of the viral replication complex, as well as the generation of the energy required for efficient viral replication [3][4][5]. Moreover, lipids can regulate the appropriate cellular distribution of viral proteins, in addition to the assembly, trafficking, and release of viral particles [6][7].

Coronaviruses firstly seize host cell intracellular membranes to create new compartments known as double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) needed for viral genome amplification. A specific phospholipid composition is required by different viruses to form the perfect replicative organelles that are suitable for their replication [8]. DMVs are membranous structures that contain viral proteins and an array of confiscated host factors, which jointly orchestrate an exclusive lipid micro-environment ideal for coronavirus replication [9]. A recent study indicated that cytosolic phospholipase A2α enzyme (cPLA2α), a crucial lipid processing enzyme belonging to the phospholipase A2 superfamily, is critical for DMVs’ formation and coronaviruses’ replication [10]. Accumulation of viral proteins and RNA, as well as creation of infectious virus progeny, were significantly reduced in the presence of cPLA2α inhibitor [10]. Similarly, increased expression of age-dependent phospholipase A2 group IID (PLA2G2D), an enzyme that usually contributes to anti-inflammatory/pro-resolving lipid mediator expression, resulted in worsened outcomes in aged mice infected with SARS-CoV, suggesting that inhibition of such factor could represent a potential therapeutic option [11]. However, to date, the change and tempering effects of specific lipids involved in lipid remodeling upon coronavirus infection stay largely unexplored.

Earlier reports have shown that most RNA viruses such as rhinoviruses show an enhancement of glucose uptake and dependence on both extracellular glucose and glutamine for optimal viral replication [12]. This glucose uptake enhancement and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-regulated glucose transporter (GLUT1) upregulation were found to be PI3K driven and reversible by PI3K inhibitor. Moreover, metabolomic studies revealed increased levels of metabolites associated with glycogenolysis, a process that has not been described so far in the context of viral infections. Lipogenesis and nucleotide synthesis were found to be elevated as well. Lack of both glutamine and glucose impaired high-titer rhinoviruses replication in cells, and the glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG) effectively repressed viral replication and reversed the rhinoviruses-induced alterations of the host cell metabolome. These findings underscore the potential of metabolic pathways as a target for host-directed antiviral therapy [12].

Citrate, which is the main carbon source for fatty acid (F.A.) or cholesterol synthesis, can usually pass across the mitochondrial membrane and is cleaved into acetyl-CoA that gets carboxylated by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) to yield malonyl-CoA [13][14][15]. On the other hand, F.A. synthase (FASN) catalyzes the production of palmitic acid (C16:0) from cytosolic acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA. The palmitic acid can then be further processed and used in the synthesis of cell membranes, storage in lipid droplets, or the palmitoylation of host and viral proteins. As for sterol biosynthesis, two units of acetyl-CoA are processed to make acetoacetyl-CoA, which then enters the metabolic 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase (HMG-CoA reductase) pathway for cholesterol production. Moreover, F.A.s can be metabolized by catabolic beta-oxidation to yield high amounts of ATP [15][16][17]. Cholesterol and F.A. are essential for viral replication as they constitute the main components of viral membranes. Hence, the metabolism of these lipids has been shown to be required for the replication of various viruses [18]. FASN enzyme is an important player in this process as it controls F.A. synthesis and can regulate the viral replication. Some viruses can even harness this process by increasing the expression of FASN and enhancing their activity [18].

As previously shown, the impact of viral infection on various lipid species has been dramatic. Wu et al. showed that the effect of treatment on SARS patients was long-lived and could significantly impact their serum metabolites. In their study, Wu et al., recruited 25 SARS survivors 12 years after their infection and compared them to healthy controls [19]. They demonstrated that SARS survivors were more susceptible to lung infections, tumors, cardiovascular disorders, and abnormal glucose metabolism compared to controls. More importantly, to this review, SARS survivors had a higher level of phosphatidylinositol and lysophosphatidylinositol compared to uninfected controls. This increase in metabolites was believed to be caused by the high dose of steroid treatment using methylprednisolone [19].

In another study, Nguyen et al. explored changes in the lipidome of primary human epithelial cells infected with rhinoviruses [20]. Post-infection untargeted lipidomics analysis of infected cells showed time-dependent changes in multiple lipid pathways and in the length of fatty acid saturation and class. These pathways implicate multiple lipid modifying enzymes, which were increased upon infection including lysocardiolipin acyltransferase (LCLAT), phosphoinositide phosphatase (PIP), and D.G. kinase amongst others that present good antiviral targets [20]. Other studies have also looked at changes in the lipidome profile after infection with viruses such as Enterovirus A71 and coxsackievirus and found that 47 lipid species/classes such as arachidonic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, and eicosapentaenoic acid were consistently upregulated after infection [21]. These data highlight the increase in lipid metabolism that occurs after viral infection where the virus highjacks and utilizes the host lipid metabolism for their own propagation.

2. Viral Internalization: Lipid-Mediated Endocytosis

Endocytosis is the process of internalization of various materials into the cell. It is used to internalize fluids, cellular components as well as various solutes. This happens through the invagination of the plasma membrane and the internalization of various components into cells through membrane vesicles. Viral entry is dependent on the attachment and fusion of viral membrane with plasma membrane through an endocytosis-mediated process [22][23]. Of high relevance to this review and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is the role of lipid rafts in viral entry into the host cells. Lipid rafts are sphingolipid-, cholesterol-, and protein-rich microdomains of the cell membrane. Lipid rafts have been found to be important to multiple viruses including SARS-CoV, especially during the early replication stage, although there was no increased angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) localization in such rafts [24]. This could be compensated by the presence of caveolins, clathrins, and dynamin that are important for the endocytosis process and viral entry. This process facilitates the fusion as well as the release of the viral genome into the host cell, where many enveloped viruses, including coronaviruses, take advantage of the low pH inside the endosomes to facilitate the fusion and viral genome release [24].

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the Betacoronavirus genus in the subgenus Sarbecovirus, which includes SARS-CoV but not MERS-CoV, which belongs to Merbecovirus subgenus [25]. The genome structure of SARS-CoV-2 has a gene order of 5′-replicase ORF1ab-S-envelope(E)-membrane(M)-N-3′, which is shared by other Betacoronaviruses [26]. The Spike (S) protein is made of two functional subunits (S1 and S2) both of which are necessary for virus entry into host cells. While S1 contains the receptor binding domain (RBD) required for viral attachment to host cell receptors, S2 facilitates the fusion of the cell and viral membranes. The RBD of the S protein from SARS-CoV-2 is well-suited for binding to the human ACE2 receptor, which is also used by the SARS-CoV albeit more efficiently in the former virus [26]. For the fusion to take place, the S protein needs to be cleaved by cellular proteases to expose the fusion sequences [27][28]. The amino acid sequence of SARS-CoV-2 S protein, unlike other Betacoronaviruses, contains a characteristic insertion of polybasic cleavage site (residues PRRA) for furin (alias PCSK3) at the junction of S1 and S2 subunits. Furin is a proprotein convertase, which is a serine proteinase. Proprotein convertases are involved in posttranslational processing of the precursors of a vast number of cellular proteins [29]. It was recently reported that SARS-CoV-2 uses the serine protease TMPRSS2 for S protein priming and it is speculated that furin-mediated precleavage at the S1/S2 site in infected cells might promote subsequent TMPRSS2-dependent entry into target cells, as reported for MERS-CoV [30].

3. Targeting Lipid Metabolism Pathways

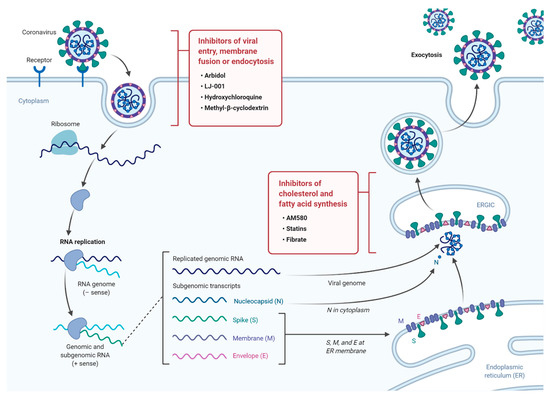

The continuous emergence of new strains of coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV-2 constitutes a major challenge as global efforts are in a race with time to identify treatments and develop new vaccines. These are generally slow processes that require extensive research and development and ultimately delay the responses to such emerging epidemics. On the other hand, the development of broad-spectrum antiviral drugs could constitute an important first response to such epidemics and enhance the impact of such responses. Pathways that are fundamental to viral attachment and fusion as well as pathways involved in the viral replication and assembly are the foundations for drug discovery. Please see Figure 1 for a summary of current anti-viral drugs that are mentioned in this article [18].

Figure 1. A diagram illustrating the life cycle of SARS-COV2 and potential lipid modifying drugs that can used as broad-spectrum antiviral drugs to inhibit viral entry, membrane fusion, or endocytosis as well as inhibition of fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis.

- Nagy, P.D.; Strating, J.R.; van Kuppeveld, F.J. Building Viral Replication Organelles: Close Encounters of the Membrane Types. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, N.Y.; Ilnytska, O.; Belov, G.; Santiana, M.; Chen, Y.H.; Takvorian, P.M.; Pau, C.; van der Schaar, H.; Kaushik-Basu, N.; Balla, T.; et al. Viral reorganization of the secretory pathway generates distinct organelles for RNA replication. Cell 2010, 141, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, D.L.; Syder, A.J.; Jacobs, J.M.; Sorensen, C.M.; Walters, K.A.; Proll, S.C.; McDermott, J.E.; Gritsenko, M.A.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, R.; et al. Temporal proteome and lipidome profiles reveal hepatitis C virus-associated reprogramming of hepatocellular metabolism and bioenergetics. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thai, M.; Thaker, S.K.; Feng, J.; Du, Y.; Hu, H.; Ting Wu, T.; Graeber, T.G.; Braas, D.; Christofk, H.R. MYC-induced reprogramming of glutamine catabolism supports optimal virus replication. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Maguire, T.G.; Alwine, J.C. ChREBP, a glucose-responsive transcriptional factor, enhances glucose metabolism to support biosynthesis in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 1951–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, M.; Graham, N.A.; Braas, D.; Nehil, M.; Komisopoulou, E.; Kurdistani, S.K.; McCormick, F.; Graeber, T.G.; Christofk, H.R. Adenovirus E4ORF1-induced MYC activation promotes host cell anabolic glucose metabolism and virus replication. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorizate, M.; Krausslich, H.G. Role of lipids in virus replication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a004820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, A.; Vera-Estrella, R.; Barkla, B.J.; Mendez, E.; Arias, C.F. Identification of Host Cell Factors Associated with Astrovirus Replication in Caco-2 Cells. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 10359–10370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.Q.; Peng, H.J. Characteristics of and Public Health Responses to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak in China. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M.; Gupta, P.; Irshad, K. Molecular basis of hepatocellular carcinoma induced by hepatitis C virus infection. World J. Hepatol. 2017, 9, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, G. Trials of BCG vaccine will test for covid-19 protection. New Sci. 2020, 246, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caddy, S. Developing a vaccine for covid-19. BMJ 2020, 369, m1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotez, P.J.; Corry, D.B.; Bottazzi, M.E. COVID-19 vaccine design: The Janus face of immune enhancement. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahase, E. Covid-19: What do we know so far about a vaccine? BMJ 2020, 369, m1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.C. Progress and Concept for COVID-19 Vaccine Development. Biotechnol. J. 2020, e2000147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh Le, T.; Andreadakis, Z.; Kumar, A.; Gomez Roman, R.; Tollefsen, S.; Saville, M.; Mayhew, S. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Vaccine designers take first shots at COVID-19. Science 2020, 368, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myint, A.; Jones, T. Possible method for the production of a Covid-19 vaccine. Vet. Rec. 2020, 186, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagam, P.; Singh, D.P.; Inda, M.E.; Batra, S. Unraveling the role of membrane microdomains during microbial infections. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2017, 33, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taube, S.; Jiang, M.; Wobus, C.E. Glycosphingolipids as receptors for non-enveloped viruses. Viruses 2010, 2, 1011–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, A.; Ablan, S.D.; Lockett, S.J.; Nagashima, K.; Freed, E.O. Phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate regulates HIV-1 Gag targeting to the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14889–14894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Pekosz, A.; Lamb, R.A. Influenza virus assembly and lipid raft microdomains: A role for the cytoplasmic tails of the spike glycoproteins. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 4634–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Nagy, P.D. RNA virus replication depends on enrichment of phosphatidylethanolamine at replication sites in subcellular membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E1782–E1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoops, K.; Kikkert, M.; Worm, S.H.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; van der Meer, Y.; Koster, A.J.; Mommaas, A.M.; Snijder, E.J. SARS-coronavirus replication is supported by a reticulovesicular network of modified endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, C.; Hardt, M.; Schwudke, D.; Neuman, B.W.; Pleschka, S.; Ziebuhr, J. Inhibition of Cytosolic Phospholipase A2alpha Impairs an Early Step of Coronavirus Replication in Cell Culture. J. Virol. 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, R.; Hua, X.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Miki, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Gelb, M.; Murakami, M.; Perlman, S. Critical role of phospholipase A2 group IID in age-related susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome-CoV infection. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 1851–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodson, L.; Gunn, P.J. The regulation of hepatic fatty acid synthesis and partitioning: The effect of nutritional state. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; DeBose-Boyd, R.A. Regulation of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.F. Regulation of fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis: Co-operation or competition? Prog. Lipid Res. 2003, 42, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G.; Pan, D.A. Regulation of fatty acid synthesis and oxidation by the AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakil, S.J.; Stoops, J.K.; Joshi, V.C. Fatty acid synthesis and its regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1983, 52, 537–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaton, N.S.; Randall, G. Multifaceted roles for lipids in viral infection. Trends Microbiol. 2011, 19, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]