The ingestion of wheat gliadin (alcohol-soluble proteins, an integral part of wheat gluten) and re-lated proteins induce, in genetically predisposed individuals, celiac disease (CD), which is charac-terized by immune-mediated impairment of the small intestinal mucosa. The lifelong omission of gluten and related grain proteins, i.e., a gluten-free diet (GFD), is at present the only therapy for CD. Although a GFD usually reduces CD symptoms, it does not entirely restore the small intesti-nal mucosa to a fully healthy state. Recently, the participation of microbial components in patho-genetic mechanisms of celiac disease was suggested.

- celiac disease

- infections

- microbiota

- parasites

- gluten-free diet

- immune response

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Celiac Disease—Introduction

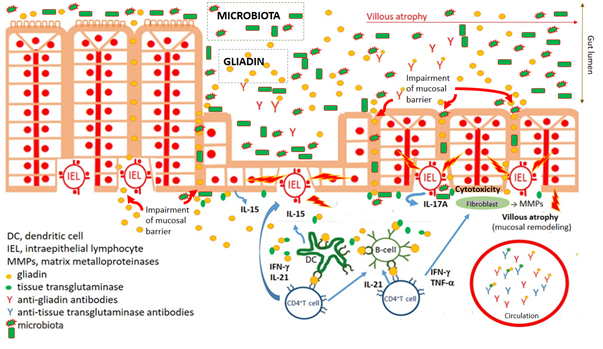

The ingestion of wheat gliadin (the alcohol-soluble part of wheat grain storage proteins, i.e., gluten) and phylogenetically related cereal proteins (secalin from rye, hordein from barley, and avenin from oat) induces celiac disease (CD) in genetically susceptible individuals bearing the human leukocyte antigens HLA-DQ2 (alleles DQA1*0501 and DQB1*0201) and HLA-DQ8 (DQA1*0301 and DQB1*0302) haplotypes [1][2][3][4][1–4]. CD affects about 1:100–200 of those who consume wheat. Helper T-cells (Th1) are the dominant effector immunocytes driving the damage to the small gut mucosa, which is characterized by villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia accompanied by malabsorption and gastrointestinal symptoms. Th1 cells activated by gliadin peptides, via antigen-presenting cells, produce high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-2, IL-6, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) that promote increased cytotoxicity of intraepithelial lymphocytes and natural killer T cells, which in turn leads to damage of the small gut (villus) enterocytes (via abundant apoptosis) and simultaneously hyperplasia of crypts. Recruitment of Th2 cells during the immune response against gliadin leads to activation of B cells, their transformation into plasma cells (plasmacytes), and the production of antibodies against gliadin as well as autoantibodies, of which those against tissue transglutaminase and endomysium are considered to be serological hallmarks of a CD diagnosis (Figure 1). Life-long adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD) is the sole rational therapy for CD, with the goal of healing pathological changes in the gut mucosa and suppressing the production of antibodies and autoantibodies [5][6][7][8][9][3,5–9]. CD is associated with several extra-intestinal phenomena, including dermatitis herpetiformis and ataxia [10][11][12][10–12]. Liver disorders, respiratory symptoms, and alveolitis have also been linked to CD [13][14][15][13–15]. This corresponds to the increased prevalence of repeated infections in CD [16][17][16,17]. Certain viral and bacterial infections occurring in early postnatal life have been significantly associated with the development of CD [18][19] [18,19].

Figure 1. Key characteristics of celiac disease pathogenesis. Impairment of mucosal barrier of small intestine and penetration of food antigens, including wheat gliadin. Gliadin fragments are deamidated by tissue transglutaminase. Deamidated gliadin fragments stimulate (boosted by adjuvant properties of microbiota) innate immune cells, counting professional antigen presenting cells (dendritic cells), which present deamidated gliadin peptides by CD4+T cells. Polarization of CD4+T lymphocyte development to Th1 cytokine profile leads to activation (intraepithelial) lymphocytes and damaging of enterocytes. Activation of fibrocytes by Th1 cytokines trigger releasing of matrix metalloproteinases mediating pathological remodeling of small gut mucosa of celiac patients. Simultaneously, antibodies against gliadin and autoantibodies against tissue transglutaminase are developed.

Although gluten is unquestionably the trigger for CD, indirect evidence suggests that microorganisms may also play an essential role in the pathogenesis of CD and can impact the onset, progression, and even clinical presentation of the disease. The evidence includes: (1) early, multiple gastrointestinal infections, the microbiome/dysbiome repertoire, early vaccinations, and consumption of antibiotics or proton pump inhibitors (which themselves can induce dysbiosis) can trigger CD [20][21][22][17,20–22]; (2) although a GFD reduces CD symptoms in most CD patients, it does not entirely restore the duodenal/jejunal mucosa to the level found in healthy individuals [23][24][25][26][23–26]; (3) onset of CD can occur in adults, i.e., years after the introduction of gluten into the diet [27]; (4) a more than 80% concordance among monozygotic, i.e., equally genetically predisposed twins in the development of CD, indicates that one’s genetic background, represented mainly by HLA-DQ2/DQ8 haplotype (and non-HLA genes), is necessary but insufficient for the development of CD [28][29][30][28–30]; and (5) intestinal dysbiosis probably exists in both patients with active CD and those with long-lasting adherence to a GFD [31][32][33][26,31–33]. There is an increase in the pathobionts Clostridium spp. and Enterobacteriaceae while potentially protective bacteria (Bifidobacterium spp. and the Lactobacillus group) are decreased in CD patients [34][35][36][32,34–36].

2. Bacterial Infections in Celiac Disease

Infectious diseases are associated with both increased morbidity and mortality in CD patients [37]. The increased susceptibility of CD patients to infections is probably explainable, even beyond the genetically determined aberration of immune system functions, by impaired nutritional conditions, malnutrition, deficiency of vitamin D, folic acid, B12, hyposplenism, and altered mucosal intestinal permeability [38][39][40][41][42][43][38–43].

It is assumed that recurrent infections increase the risk of CD development [44][45][44,45]. Children suffering from more than ten gastrointestinal (or respiratory) infections are at a higher risk of CD development compared to children with less than four infection events during the reference period [21,45]. Additionally, mucosal infections may contribute to the impairment of immune tolerance to gluten, leading to tissue damage in CD patients [46][47] [46].

Infections, mainly those induced by Clostridium difficile, Helicobacter pylori, and Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcus), are frequently associated with CD. A significantly higher hazard ratio, linked to Clostridium difficile, was found in CD patients compared to controls. A higher incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in CD was found in a large-scale population-based cohort study involving more than 28 thousand CD patients and more than 141 thousand controls; the incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in the former group was estimated at 56/100,000 person-years in contrast to the incidence of 26/100,000 in controls (i.e., the general population and non-CD controls). Interestingly, the risk of Clostridium difficile infection was highest in the first 12 months after diagnosis (hazard ratio: 5.2, p < 0.0001) and remained high, for up to five years, compared to controls [47].

There is a risk of CD in children suffering from peptic ulcers: Helicobacter pylori infection was present in 63% of patients with CD and 44% of non-celiac peptic ulcers; however, the difference was not statistically significant. Of the entire ulcer group, 11% of CD patients with peptic ulcers were negative for Helicobacter pylori infection [48]. The Helicobacter and Megasphaera genera were highly abundant in duodenal biopsy samples from adult CD patients compared to first-degree relatives and controls [49]. However, the role of these bacteria in the pathogenesis of CD has not been completely elucidated. It is a matter of debate whether these bacteria elicit pathological changes in the small gut mucosa of the celiac patients or the presence of these bacteria, due to immune dysregulation or intrinsic conditions in celiac patients, favor colonization by these bacterial species [30].

Nonetheless, CD patients are at increased risk for the development of bacterial infections [50]. There are also rare reports on CD patients with respiratory diseases; a Swedish population-based 2006 study reported that the tuberculosis risk was 3–4 times higher in CD patients [51][52][51,52]. CD is associated with an increased risk of pneumococcal infection. Invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcus) infection is a particularly dangerous co-morbidity in CD patients. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a causative agent of pneumonia, bacterial meningitis, and sepsis. One of the first comprehensive studies concerning pneumococcal infection was performed in England. The objective of the study was to determine the risk (rate ratio) of pneumococcal infection in patients with CD in a population in: (1) the Oxford region (1963–1999); and (2) the whole of England (1998–2003). The high rate of pneumococcal infections in CD patients persisted beyond the first year after the CD diagnosis. It should be noted that the pneumococcal vaccination was available at the time of the all-England study but not at the time of the Oxford study, which influenced study conditions [42]. A Swedish study by Röckert Tjernberg et al. [41] showed an increased risk (although statistically insignificant) of invasive pneumococcal disease in CD. The risk estimate was similar after considering comorbidities, socioeconomic status, and education level [41]. An increased risk of bacterial pneumonia, especially in children and young people with CD, was found by Simons et al. [40] and Canova et al. [53]. Interestingly, the risk of bacterial pneumonia was significantly increased before the CD diagnosis [53][40,53]. For this reason, pneumococcal vaccination in individuals at risk of developing CD is the most effective way to prevent streptococcal pneumonia. Preventive pneumococcal vaccination should be considered for CD patients between 15 and 64 years who have not received the pneumococcal vaccination series in childhood [40]. The beneficial effect of the vaccination in CD, however, depends on splenic function [54]. Studies have reported a high prevalence of respiratory tract infections in CD patients with hyposplenism. Hyposplenism, along with malnutrition and vitamin deficiency, is the leading cause of susceptibility to respiratory infections such as streptococcal pneumonia. Interestingly, hyposplenism in adult CD patients ranges 19–80% [40]. Hyposplenism is associated with a fourfold increase in the risk of fulminant and fatal septicemia from encapsulated organisms in patients with CD [55]. The British Society of Gastroenterology recommends routine pneumococcal vaccination (pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine, PCV13 followed, at least eight weeks later, by the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV23)) for all adult patients diagnosed with CD [50,52]. Defense against pneumococcal infection in CD patients is probably based on cellular mechanisms because complement changes after Streptococcus pneumoniae infection seem similar in children with and without CD. It is unlikely that complement contributes to increased sensitivity to invasive pneumococcal infection in these individuals [56].

Moreover, vulnerability to respiratory infections in CD patients may also be caused by impaired airway epithelium function, e.g., a defect in nasal mucociliary clearance, which has been found in CD patients. A defect in nasal mucociliary clearance increases the risk of lung infections. Nasal mucociliary clearance time was significantly prolonged in pediatric CD patients compared to healthy children. Interestingly, no relation was found between the age at diagnosis, histopathological stage, or compliance with a GFD relative to the nasal mucociliary clearance time in CD patients [57] [57].

Adult CD patients were shown to be at significantly increased risk of sepsis (hazard ratio = 2.6), especially pneumococcal sepsis (3.9). A similar situation exists in CD children (1.8) [43]. Moreover, respiratory infections are closely related to the increased mortality associated with CD. The cause-specific mortality risks in the periods before and after introducing accurate and specific serological tests for the diagnosis of CD were studied by Grainge et al. [58]. CD mortality did not change significantly after introducing routine serological testing as part of the CD diagnosis [58]. The Swedish national mortality register, which includes approximately ten thousand CD patients, was analyzed to determine the cause of death in these patients. The cumulative mortality risk for cancer, digestive disease, and respiratory diseases (including pneumonia, allergic disorders, and asthma) was significantly elevated in CD patients [59].

3. Viral Infections Associated with Celiac Disease

Patients with CD were described to have elevated antibody levels to human adenovirus serotype 2, which indicates infection by this virus [60][61][62][60–62]. Kagnoff et al. suggested that molecular mimicry may play a pathogenic role, i.e., immunological cross-reactivity between antigenic epitopes of viral proteins and gliadins via shared antigenic determinants. These authors characterized a sequence homology between the E1b region of human adenovirus serotype 12, isolated from the human intestinal tract, and an A-gliadin (an alpha-gliadin component known to be harmful to the small intestine of CD patients) [60][61][60,61].

Generally, it was assumed that the Reoviridae family (mainly reoviruses and rotaviruses), adenoviruses, the respiratory syncytial virus, herpes simplex type 1, hepatitis C and B viruses, enteroviruses, the influenza virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus might play a role in CD development [63][19,63]. Reoviridae infections are common and usually nonpathogenic, although some viruses in this family, namely the rotaviruses, can cause severe diarrhea and abdominal discomfort in children [64]. High rates of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children with CD were found [16], and vaccination against rotavirus prevents the onset of CD [65].

Rotavirus infections have been proposed to trigger CD and type 1 diabetes mellitus in genetically susceptible children via molecular mimicry. When measuring the prevalence of diseases in a group of children vaccinated with RotaTeq (Kenilworth, NJ), a Finnish study showed that the prevalence of CD was significantly lower in vaccinated children than in those receiving a placebo [66]. However, the introduction of the rotavirus vaccination in Italy did not affect CD prevalence in Italian children [67]. Moreover, several viruses, namely rotaviruses and astroviruses, directly increase gut mucosal permeability [68]. Reoviruses promote enterocyte apoptosis and may trigger a pro-inflammatory response against ingested food antigens [69].

An essential role for reovirus infections in the pathogenetic mechanism of CD was recently suggested [69][70][69,70]. Using an animal model of human disease, reovirus was shown to disrupt intestinal immune homeostasis, promote immunopathology by suppressing peripheral regulatory T cells, and activate the pathogenic Th1 response, which led to the loss of immune tolerance to gliadin. The central role of IRF1 (interferon regulatory factor 1) in the reovirus-mediated Th1 response against dietary antigen was also demonstrated [69]. Anti-reovirus antibody titers were shown to be higher in a cohort of celiac patients consisting of patients with active CD and those on a GFD in contrast to control individuals. CD patients on a GFD with high anti-reovirus antibody titers possess significantly higher interferon regulatory factor 1 expression in the small intestinal mucosa compared to those patients with low-reovirus antibody titers. Nevertheless, there was no direct relationship between anti-reovirus antibody levels and the level of IRF1 expression. These results support the opinion that viruses may influence the transcriptional program of the host for long periods of time [70].

The association between CD and prior respiratory syncytial virus infection or viral bronchiolitis has been studied [39]. Approximately four thousand children suffering from CD (March III stage of villous atrophy) were statistically analyzed for respiratory syncytial virus infections or viral bronchiolitis before their CD diagnosis. Prior to the CD diagnosis, 0.9% of CD patients, in contrast to 0.6% of matched controls, were infected by the respiratory syncytial virus. The odds ratios were similar for girls and boys. Interestingly, the highest odds ratios were found in patients developing CD before one year of age. In this study, 3.4% of CD patients and 2% of matched controls had viral bronchiolitis, regardless of the viral agent [39].

Enteroviruses have been found in the small gut mucosa of CD patients [71]. Recently, early childhood exposures to enteroviruses, between the age of one and two years, was associated with an increased risk of CD [72].

The CD-associated DQA1∗0501/DQB1∗0201 haplotype causes susceptibility to herpes infection due to delayed maturation of the gastrointestinal immune system and mucosal overexpression of the epidermal growth factor receptor and IL-33 [73]. CD is an immune-mediated disease associated with a high rate of non-response to the viral hepatitis B vaccination. Proper CD treatment might lead to a positive response to the hepatitis B vaccination [74]. Interestingly, a significantly increased risk for the development of CD after vaccination with the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine was found in a Danish and Swedish population study [75].

Influenza has also been linked to autoimmune conditions. Mårild et al. found that children with active CD were at increased risk for influenza (hazard ratio of 2.5) [38]. Analysis of the risk of CD after influenza in Norwegians revealed a significantly increased hazard ratio for CD after seasonal and pandemic influenza. The hazard ratio remained significantly increased one year after influenza, while the hazard ratio for influenza after CD diagnosis was not significant, although individuals with CD were at increased risk of hospital admission for influenza (2.1) [76][38,76].

A number of autoantibodies and antibodies against food antigens develop in patients with active CD in contrast to healthy individuals. Conversely, serum levels of IgG antibodies to cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus were lower in CD patients than healthy controls [19]. More recently, an inverse correlation was described among anti-cytomegalovirus, anti-Epstein-Barr virus, and anti-herpes simplex type 1 virus IgG antibody levels and levels of autoantibodies against tissue transglutaminase [77].