- preclinical models

- androgen receptor

- prostate cancer

- hormone treatment

- ARSI

- ARTA

- treatment resistance

1. Introduction

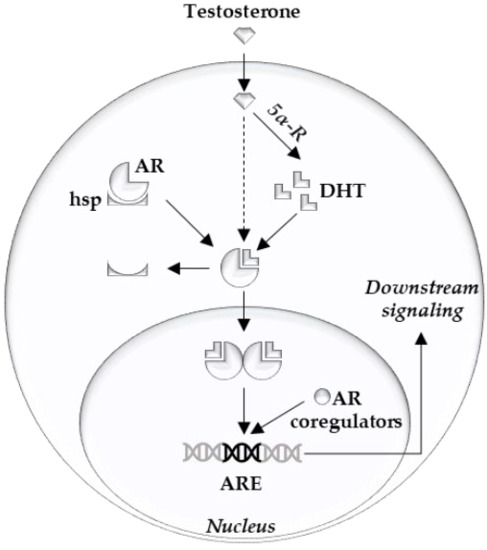

The androgen receptor (AR) is the main driver of proliferation in prostate cancer (PCa) cells, and thus is an important therapeutic target [1][2]. It consists of three structural components: the C terminal domain/ligand binding domain, the DNA binding domain, and the N terminal domain [3]. Ligand binding, dimerization, and complex formation with coregulators contribute to the downstream AR signaling [4] (

Figure 1. Overview of intracellular androgen action. Androgen receptor (AR), heat shock proteins (hsp), dihydrotestosterone (DHT), 5-alpha reductase (5α-R), androgen response element (ARE).

Clinical targeting of the AR is achieved by LHRH agonists/antagonists and abiraterone or by blocking the AR ligand binding pocket with anti-androgens (e.g., apalutamide, darolutamide, and enzalutamide). Unfortunately, curative treatment of advanced PCa by these AR signaling inhibitors is prevented by the occurrence of resistance mechanisms [1][2].

To become resistant against these therapies, PCa cells have to overcome the lack of growth signals. The mechanisms can be broadly categorized into two groups: (1) mechanisms that reactivate AR signaling output (i.e., AR overexpression, mutation and splice variants, glucocorticoid receptor takeover, androgen synthesis); and (2) mechanisms that bypass the AR by providing growth signals via other means (i.e., alterations in cell cycle regulators, DNA repair pathways, PI3K/PTEN alterations, trans-differentiation into AR independent phenotypes such as neuroendocrine cells).

2. Overview of Preclinical PCa Models

2.1. Prostate Cancer Derived Cell Lines

2.1. Prostate Cancer Derived Cell Lines

2.1.1. Cell Lines

Table 1. Overview commonly used prostate cancer cell lines. Wild type (WT); androgen receptor (AR). Adapted from [6][7][8].

| Cell Line | AR/PSA | Hormone Resistant/Sensitive | Direct/Xenograft (Indirect) | Specific Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| LNCaP | + | Sensitive | Direct | T877A AR mutant, PTEN -, androgen dependent |

| LAPC-4 | + | Sensitive | Xenograft | P53 mutant, WT PTEN |

| Bone metastasis | ||||

| VCaP | + | Sensitive | Xenograft | Amplified WT AR, AR splice variants, TMPRSS-ERG fusion |

| MDA PCa 2a/b | + | Sensitive | Direct | AR mutants L702H and T878A |

| PC3 | − | Resistant | Direct | |

| CWR22(Rv1) | + | Resistant | Xenograft | H875Y AR mutant, AR splice variants, WT PTEN, Zinc Finger Duplication |

| Organ metastasis | ||||

| DU-145 (brain) | − | Resistant | Direct | |

| DuCaP (dura) | + | Sensitive | Xenograft | Amplified WT AR |

LNCaP is a cell line derived from a lymph node metastasis. It harbors a T877A AR mutation, with ligand promiscuity and has only a modest potential to form xenografts in nude mice [9]. It has multiple derivative cell lines, differing from the maternal LNCaP cell lines on different points: C4-2b (PSA +, bone metastatic in mice), LNCaP-abl (androgen-resistant, androgen depleted medium), LNCaP-AR (androgen-resistant, tissue culture), ResA and B (androgen- and anti-androgen-resistant) [10][11]. VCaP cells come from a metastatic lesion and have a wild-type, yet amplified, AR. VCaP cells are especially interesting in preclinical research as they express the TMPRSS2-ERG gene arrangement, commonly seen in PCa patients [12]. DuCaP is derived from a hormone refractory xenograft of a dura mater metastasis and is expressing PSA and overexpressing wildtype AR [7][13]. Multiple LAPC cell lines are androgen-responsive and developed from a xenograft of a PCa lymph node (LAPC-4) and bone (LAPC-9) metastasis. LAPC-4 is characterized by mutations of p53 and wildtype PTEN [14]. DU-145 are derived from a PCa brain metastasis. It does not express AR and is therefore hormone-insensitive [15]. PC3 cells are grown from a PCa bone metastasis and are, similarly to DU-145, AR negative. [16]. Some studies suggested PC3 cells to have neuroendocrine features reflecting small cell PCa and stem-like features [17][18]. 22Rv1 is a cell line derived from a relapsing xenograft of the CWR22 cell line in mice that were castrated [19]. Its AR is mutated (H874Y), while expressing a truncated AR in parallel because of an intragenic duplication of exon 3 and has a wildtype PTEN. It is mostly used in research involving splice variants of the AR [8]. MDA PCa 2A is a cell line derived from bone metastasis, being AR positive, harboring AR mutants L702H and T878A [6][20].

The big advantages of these cell lines are their relative simplicity and ease of culturing in different conditions. This enables the rapid validations of hypotheses and the simultaneous testing of multiple compounds. Also beneficial is the high amount of data that are already available on them (i.e., on DepMap and CCLE) [21][22]. Each cell line should, however, be considered as a proxy of a very specific type of PCa (i.e., AR/PSA positive, TMPRSS2-ERG fusion positive, PTEN status) (Table 3).

2.1.2. Xenografts and 3D models

Three-dimensional cell cultures can similarly be valuable in creating a basis to investigate cell–cell interactions. Cell lines can consequently be studied in a tumor microenvironment [8][28]. This can be made from artificial or biologic materials. The effects of the artificially engineered 3D scaffolds on the cells and their androgen sensitivity remain under investigation [28][29].

2.2. Genetically-Engineered Mouse Models (GEMM)

Transgenic technology has enabled mimicking genetic changes that have been discovered in PCa. The genes under investigation can be knocked out or altered specifically in mouse prostate luminal cells. In this way, GEMMs of different pathways that lead to treatment resistance in humans have been recreated, of which the most commonly altered mechanisms are represented in

2.2. Genetically-Engineered Mouse Models (GEMM)

Table 2.

| GEMM | PCa Inducement |

Specific Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Localized PCa alterations | ||

| TMPRSS-ERG fusion | + − | Modest phenotype on its own, additive effect with PTEN loss |

| SPOP mutation | + − | Modest phenotype on its own, additive effect with PTEN loss |

| Advanced PCa alterations | ||

| PTEN loss | + | Most frequent GEMM, Clinical stage ranges between models. Additive effects with other alterations |

| Tumor surpressor genes losses (RB/p53) | + − | Modest phenotype on its own, additive effect with PTEN/BRCA mutations/RB/p53 losses |

| DNA repair genes mutation | + | Fewer models available, study of PARP inhibitors. Additive effects with PTEN/RB/p53 losses |

| Oncogenes | + | Clinical stage ranges between Myc levels, additive effects with p53, and PTEN models |

| Other models—mechanistic studies of targets | ||

As a consequence, human PCa phenotypes can be mimicked in GEMMs, and murine metastatic signatures that can be relevant in humans can be discovered [33]. While inter-species differences have to be considered, these approaches have led to major breakthroughs and provided an increased potential to pre-clinical in vivo research [31][32].

Besides mimicking PCa phenotypes, GEMMs can also be used to study non-cancerous targets of hormone therapy. Multiple models studying the AR have been created from this perspective. Although these models do not directly result in novel prostate cancer treatments, their impact is indirect by improving the understanding of the AR and its pathways [34][35] (

Table 2).

).For example, in the TRAMP model, researchers altered the expression of SV40 antigens to create prostate cancer models reflecting the heterogeneous AR and p53 expression and castration response seen in patients [36].

2.3. Patient-Derived Models

Different patient-derived models have been reported, including primary cell cultures, patient-derived explants, and patient-derived xenografts [28]. These models are similar to other models, but are constructed from an actual tumor (

2.3. Patient-Derived Models

Table 3.

| Model | Advantages/Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

|

PCa cell line experiments | + Easy to culture, high-throughput system − Very homogeneous, not reflective of clinical tumors |

|

Genetically modified PCa cell lines | + Easy validation of de novo resistance mechanisms and alterations from databases − Acquired resistance more difficult to study |

|

3D cell cultures/organoids | + Study of Cell-Cell interaction − Scaffold material can alter cellular processes |

|

Mouse Xenografts of PCa | + Study of metastasis and treatment response in vivo + Working endocrine system − Limitations similar to injected cell lines |

|

Genetically modified mouse models | + In vivo validation of genetic alterations and underlying pathways − Inter species differences, questionable generalizability to human prostate cancers |

|

Patient derived cell lines | + Good correlation with specific human tumor + Reproducibility of experiments, high throughput − Only representing a certain tumor type, no cell-cell interaction |

|

Patient derived tissue cultures | + Excellent representation of respective type of prostate cancer − Limited life span, cannot be propagated |

|

Patient derived 3D cell cultures/organoids | + Study of Cell-Cell interaction in specific tumor subtypes + Medium to High throughput − Scaffold material can alter cellular processes − Technically challenging |

|

Patient derived Xenografts | + Study of metastasis and treatment of a certain tumor in vivo + Working endocrine system − No immune system, overgrowing murine tissue, tissue collection only at endpoint. |

Section 2.2, or they were grown in Matrigel to enable 3D culture. More recently, conditions have been optimized for 3D cultures (i.e., with printed scaffolds), spheroids, and organoids. As such, these primary cultures offer the possibility to expand tumor cells in vitro and even can be genetically modified. This enables their use in medium and high throughput assays for drug screening [28]. Although technically challenging, these models allow a detailed analysis in the study of the tumor microenvironment and cell–cell interactions [37]. Patient-derived organoids were successfully developed by Gao and colleagues in advanced disease stages [38]. More recently, these models have been shown to be very promising in reflecting rare tumor types (i.e., NEPC) and validating novel translational research methods (i.e., validation of single cell sequencing of prostate cancer) [39][40].

Patient-derived explants consist of primary tumor biopsies that are kept in their integrity in culture ex vivo. The culture conditions have been optimized considerably so that these models retain the functional and structural characteristics of the tissue, which enables their successful use in preclinical studies [41][42]. Consequently, these models create robust preclinical findings. Unfortunately, they cannot be propagated and will undergo changes after one or two weeks of culture, which limits their use to short term studies.

Patient-derived xenograft models are created by inserting tumor tissue in nude mice (see

, or they were grown in Matrigel to enable 3D culture. More recently, conditions have been optimized for 3D cultures (i.e., with printed scaffolds), spheroids, and organoids. As such, these primary cultures offer the possibility to expand tumor cells in vitro and even can be genetically modified. This enables their use in medium and high throughput assays for drug screening [28]. Although technically challenging, these models allow a detailed analysis in the study of the tumor microenvironment and cell–cell interactions [37]. Patient-derived organoids were successfully developed by Gao and colleagues in advanced disease stages [38]. More recently, these models have been shown to be very promising in reflecting rare tumor types (i.e., NEPC) and validating novel translational research methods (i.e., validation of single cell sequencing of prostate cancer) [39,40].Section 2.1.2. These models allow timely interventions to be performed in living animals with a complete endocrine system. Downsides to xenografting are the lacking immune system, the gradual overgrowth of murine stromal cells, and the restriction to collect tissue only at the harvest time point [28].

. These models allow timely interventions to be performed in living animals with a complete endocrine system. Downsides to xenografting are the lacking immune system, the gradual overgrowth of murine stromal cells, and the restriction to collect tissue only at the harvest time point [28].