Glycolysis is a crucial metabolic process in rapidly proliferating cells such as cancer cells. Phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1) is a key rate-limiting enzyme of glycolysis. Its efficiency is allosterically regulated by numerous substances occurring in the cytoplasm. However, the most potent regulator of PFK-1 is fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (F-2,6-BP), the level of which is strongly associated with 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase activity (PFK-2/FBPase-2, PFKFB). PFK-2/FBPase-2 is a bifunctional enzyme responsible for F-2,6-BP synthesis and degradation. Four isozymes of PFKFB (PFKFB1, PFKFB2, PFKFB3, and PFKFB4) have been identified. Alterations in the levels of all PFK-2/FBPase-2 isozymes have been reported in different diseases.

- PFKFB3

- PFKFB4

- PFK-2

- 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2

- 6-bisphosphatase

- 3PO

- PFK-158

- PFK-15

- autophagy

- angiogenesis

- cancer

1. Introduction

Glycolysis is an essential enzymatic process in human cell metabolism. It participates in the production of substrates that are required in multiple biochemical pathways, such as the tricarboxylic (TCA) acid cycle, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and fatty acids and cholesterol synthesis. In normal human cells (with the exception of red blood cells), anaerobic reactions predominate in the metabolism under reduced oxygen conditions. However, in 1927, Otto Warburg reported an essential role of glycolysis in cancer cells regardless of oxygen concentration in the tumor microenvironment [1][2][3]. This reprogramming of cancer cell metabolism is not only responsible for its aggressive growth but may also cause a beneficial decrease in Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) generation and key metabolites for cell growth [4]. It is worth noticing that a similar shift in metabolism is found in proliferative normal cells such as lymphocytes and endothelial cells in angiogenesis [5]. In recent years, targeting key regulatory steps of glycolysis has increasingly become an area of interest among scientists. There are many reports on novel inhibitors affecting distinct molecular targets in this process [6]. Amino acid sequence alterations leading to changes in enzyme catalytic activity have been detected in numerous proteins involved in glycolysis in different types of cancer [7].

Glycolysis is an essential enzymatic process in human cell metabolism. It participates in the production of substrates that are required in multiple biochemical pathways, such as the tricarboxylic (TCA) acid cycle, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and fatty acids and cholesterol synthesis. In normal human cells (with the exception of red blood cells), anaerobic reactions predominate in the metabolism under reduced oxygen conditions. However, in 1927, Otto Warburg reported an essential role of glycolysis in cancer cells regardless of oxygen concentration in the tumor microenvironment [1,2,3]. This reprogramming of cancer cell metabolism is not only responsible for its aggressive growth but may also cause a beneficial decrease in Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) generation and key metabolites for cell growth [4]. It is worth noticing that a similar shift in metabolism is found in proliferative normal cells such as lymphocytes and endothelial cells in angiogenesis [5]. In recent years, targeting key regulatory steps of glycolysis has increasingly become an area of interest among scientists. There are many reports on novel inhibitors affecting distinct molecular targets in this process [6]. Amino acid sequence alterations leading to changes in enzyme catalytic activity have been detected in numerous proteins involved in glycolysis in different types of cancer [7].

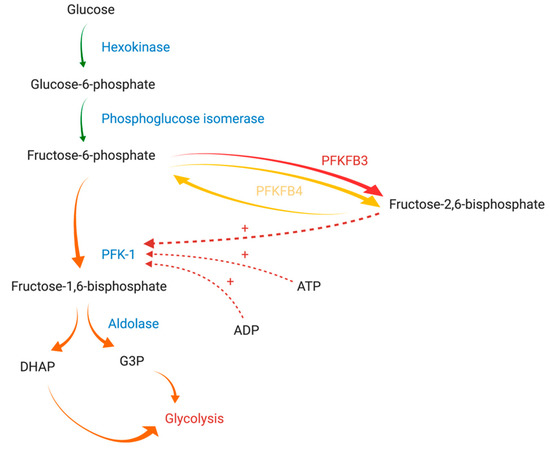

Glycolysis intensity is regulated by the activity of three physiologically irreversible enzymes: hexokinase, phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), and pyruvate kinase. PFK-1 is the main rate-limiting enzyme of glycolysis and is responsible for the synthesis of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate from fructose-6-phosphate (F-6-P). Its activity is regulated by cytoplasmically localized metabolic products, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), F-6-P, and fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (F-2,6-BP) (

) [8]. Of these compounds, F-2,6-BP, a product of the reaction catalyzed by 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (PFK-2/FBPase-2, PFKFB), is the most potent positive allosteric effector of PFK-1 [9]. PFK-2/FBPase-2 is a bifunctional enzyme responsible for the catalyzation of both the synthesis and degradation of F-2,6-BP mediated through its N-terminal domain (2-Kase) and C-terminal domain (2-Pase), respectively [10]. Of note, the active site of the 2-Kase domain has two distinct areas (the F-6-P binding loop and ATP-binding loop) essential for its function [4].

Figure 1. The graphical presentation of PFK-1 regulation by PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 adapted from Yi et al. (2019) and Clem et al. (2008) [11][12]. Diverse arrows colors are used to express the differences between reactions enhancement: (green) normal, (yellow) moderately enhanced, (orange) strongly enhanced, (red) extremely enhanced. Abbreviations: PFK-1 - phosphofructokinase-1; PFKFB3: 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase isozyme 3; PFKFB4: 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase isozyme 4; ATP: adenosine triphosphate, ADP: adenosine diphosphate, DHAP: dihydroxyacetone phosphate; G3P: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. Created with

In humans, PFK-2/FBPase-2 is encoded by four different genes: PFKFB1, PFKFB2, PFKFB3, and PFKFB4 [13]. Thus far, four different PFK-2/FBPase-2 isozymes (PFKFB1, PFKFB2, PFKFB3, and PFKFB4) have been identified. Isozymes are characterized by tissue and functional specificity [14]. PFKFB1 can be found in the liver and skeletal muscle, PFKFB2 predominates in cardiac muscle, PFKFB3 is ubiquitously expressed, while PFKFB4 occurs mainly in testes [11]. The overexpression of two isozymes (PFKFB3 and PFKFB4) has been demonstrated in various solid tumors and hematological cancer cells [15][16][17].

In humans, PFK-2/FBPase-2 is encoded by four different genes: PFKFB1, PFKFB2, PFKFB3, and PFKFB4 [13]. Thus far, four different PFK-2/FBPase-2 isozymes (PFKFB1, PFKFB2, PFKFB3, and PFKFB4) have been identified. Isozymes are characterized by tissue and functional specificity [14]. PFKFB1 can be found in the liver and skeletal muscle, PFKFB2 predominates in cardiac muscle, PFKFB3 is ubiquitously expressed, while PFKFB4 occurs mainly in testes [11]. The overexpression of two isozymes (PFKFB3 and PFKFB4) has been demonstrated in various solid tumors and hematological cancer cells [15,16,17].

Furthermore, due to slight differences in amino acid sequences at key sites for enzymatic activity, all of the isozymes have a different affinity for the synthesis or degradation of F-2,6-BP. Their activity is expressed as the kinase/phosphatase ratio (also termed the 2-Kase/2-Pase activity ratio) [11]. This ratio is about 4.6/1 for PFKFB4 and 730/1 for PFKFB3, while it does not exceed 2.5/1 for PFKFB1 and PFKFB2. Isoforms commonly expressed in tumors satisfy increased energetic requirements of neoplastic cells more efficaciously. Thus, glycolysis, the hallmark of malignancy, might be vulnerable to the therapy affecting only isoforms characterized by a high kinase/phosphatase ratio [10][18].

Furthermore, due to slight differences in amino acid sequences at key sites for enzymatic activity, all of the isozymes have a different affinity for the synthesis or degradation of F-2,6-BP. Their activity is expressed as the kinase/phosphatase ratio (also termed the 2-Kase/2-Pase activity ratio) [11]. This ratio is about 4.6/1 for PFKFB4 and 730/1 for PFKFB3, while it does not exceed 2.5/1 for PFKFB1 and PFKFB2. Isoforms commonly expressed in tumors satisfy increased energetic requirements of neoplastic cells more efficaciously. Thus, glycolysis, the hallmark of malignancy, might be vulnerable to the therapy affecting only isoforms characterized by a high kinase/phosphatase ratio [10,18].

2. PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 in Cancer

PFK-2/FBPase-2 family members, PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 in particular, are overexpressed in numerous malignancies. PFKFB3 is frequently found in breast cancer [19][20][21][22], colon cancer [19], nasopharyngeal carcinoma [23], pancreatic cancer [24], gastric cancer [24], and many other neoplasms. Similarly, increased transcription of PFKFB4 is observed in pancreatic cancer [24], gastric cancer [24], ovarian cancer [25], breast cancer [19][26], colon cancer [19][27] and glioblastoma [28]. The significance of PFKFB3 level has been reported in cancer cells but also in tumor-related cells such as cancer stem cells. Furthermore, lower PFKFB3 and PFK-I expression levels have been demonstrated in induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells compared to cancer and cancer stem cells (CSCs). This distinct expression pattern of PFKFB3 may improve the timely detection of CSCs [21].

PFK-2/FBPase-2 family members, PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 in particular, are overexpressed in numerous malignancies. PFKFB3 is frequently found in breast cancer [35,59,64,65], colon cancer [35], nasopharyngeal carcinoma [66], pancreatic cancer [67], gastric cancer [67], and many other neoplasms. Similarly, increased transcription of PFKFB4 is observed in pancreatic cancer [67], gastric cancer [67], ovarian cancer [68], breast cancer [35,69], colon cancer [35,70] and glioblastoma [71]. The significance of PFKFB3 level has been reported in cancer cells but also in tumor-related cells such as cancer stem cells. Furthermore, lower PFKFB3 and PFK-I expression levels have been demonstrated in induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells compared to cancer and cancer stem cells (CSCs). This distinct expression pattern of PFKFB3 may improve the timely detection of CSCs [64].

Influence of PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 on Carcinogenesis

PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 affect carcinogenesis and cancer metabolism in a multidirectional manner. Both isozymes participate in the regulation of glucose metabolism through enhancing glycolysis and PPP. These enzymatic reactions are crucial for cancer development [11]. Increased glucose metabolism through glycolysis enables cancer cells to survive in a microenvironment with limited oxygen supply and produce lactate which acidifies the adherent tissues and thus accelerates metastatic development. On the other hand, redirection of glucose to PPP allows for the synthesis of lipids and nucleic acids essential for the growth of cancer cells. The expression of both enzymes is induced by hypoxia, thereby facilitating nonoxidative glucose-dependent energetic metabolism of the cell. PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 stimulate glucose uptake and boost glycolytic flux to cancer cells by increasing F-2,6-BP, which is a compound promoting glucose utilization by glycolysis [8]. Both proteins are directly engaged in the production of ATP and Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), the synthesis of nucleic acids, and thus cancer cell growth.

3. Targeting PFK-2 Isozymes in Malignancies

3.1. Outline of the Development of Inhibitors

Reports on the importance of PFKFB3 and PFKFB4 in cancer development and progression strongly suggest that these isozymes may represent promising targets for new potent personalized therapies in cancer treatment. This prompted research groups to investigate the efficacy of selective inhibitors.In 1984, Sakakibara et al. identified a binding site of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase for Fru-6-P using N-bromoacetylethanolamine phosphate (BrAcNHEtOP) and 3-bromo-1,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone 1,4-bisphosphate [29]. The inhibitory properties of these compounds were later confirmed in both in vitro and in vivo models. However, these inhibitors were not specific and therefore scientists continued to develop novel compounds [30][31]. The first-in-class small molecule PFKFB3 inhibitor, 3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one, also known as 3PO was synthesized by Clem et al. in 2008 [12]. This compound was computationally identified by screening and docking using ChemNavigator software with a homologous model of the PFKFB3 isozyme, previously generated based on a PFKFB4 crystal structure from rat testes [4][32]. To date, 3PO has been the best-known inhibitor of PFKFB3, chemically belonging to the chalcone group. Its anticancer properties have been demonstrated in experimental models of several types of cancer, including breast cancer [33], ovarian cancer [34], melanoma [35], and bladder cancer [36]. The main factors limiting the potential use of 3PO in clinical trials include poor solubility and difficulty in obtaining sufficiently high concentrations to achieve potency [4]. In 2011, Akter et al. successfully attempted to use a nanocarrier to improve its efficacy in cancer treatment. They conjugated 3PO to micelles prepared from poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(aspartate) [PEG-p(ASP)], which resulted in achieving 2% wt. drug-loading in the nanocarrier polymer. Its favorable properties were observed in Jurkat, HeLa, and LLC cells [37]. In addition, it was shown that cancer cells became more sensitive to microtubule poisons, chemical compounds with the ability to bind to tubulin, thus preventing the formation of microtubules after 3PO treatment [11][38]. Since 3PO is not selective enough, more specific and selective novel PFKFB3 inhibitors were developed in the following years.

In 1984, Sakakibara et al. identified a binding site of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase for Fru-6-P using N-bromoacetylethanolamine phosphate (BrAcNHEtOP) and 3-bromo-1,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone 1,4-bisphosphate [142]. The inhibitory properties of these compounds were later confirmed in both in vitro and in vivo models. However, these inhibitors were not specific and therefore scientists continued to develop novel compounds [32,143]. The first-in-class small molecule PFKFB3 inhibitor, 3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one, also known as 3PO was synthesized by Clem et al. in 2008 [12]. This compound was computationally identified by screening and docking using ChemNavigator software with a homologous model of the PFKFB3 isozyme, previously generated based on a PFKFB4 crystal structure from rat testes [4,144]. To date, 3PO has been the best-known inhibitor of PFKFB3, chemically belonging to the chalcone group. Its anticancer properties have been demonstrated in experimental models of several types of cancer, including breast cancer [145], ovarian cancer [52], melanoma [107], and bladder cancer [146]. The main factors limiting the potential use of 3PO in clinical trials include poor solubility and difficulty in obtaining sufficiently high concentrations to achieve potency [4]. In 2011, Akter et al. successfully attempted to use a nanocarrier to improve its efficacy in cancer treatment. They conjugated 3PO to micelles prepared from poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(aspartate) [PEG-p(ASP)], which resulted in achieving 2% wt. drug-loading in the nanocarrier polymer. Its favorable properties were observed in Jurkat, HeLa, and LLC cells [147]. In addition, it was shown that cancer cells became more sensitive to microtubule poisons, chemical compounds with the ability to bind to tubulin, thus preventing the formation of microtubules after 3PO treatment [11,105]. Since 3PO is not selective enough, more specific and selective novel PFKFB3 inhibitors were developed in the following years.In 2011, Seo et al. determined the crystal structure of PFKFB3 and identified new inhibitors such as N4A and YN1. This study not only revealed two inhibitors with increased selectivity for PFKFB3, but was also essential for future targeted drug design due to the extension of knowledge regarding PFKFB3 structure [39].

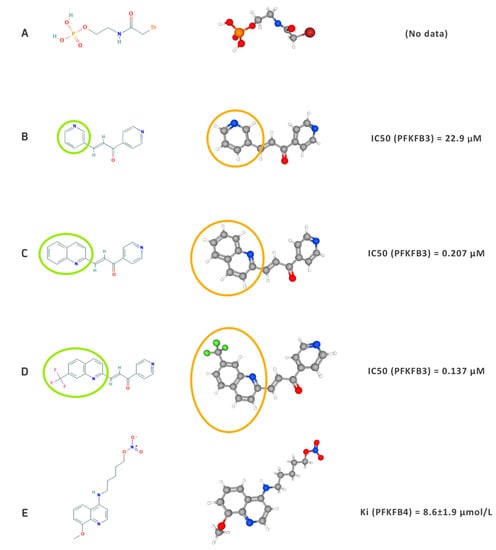

In 2011, Seo et al. determined the crystal structure of PFKFB3 and identified new inhibitors such as N4A and YN1. This study not only revealed two inhibitors with increased selectivity for PFKFB3, but was also essential for future targeted drug design due to the extension of knowledge regarding PFKFB3 structure [148].PFK15, a derivative of 3PO, was another chalcone compound developed to inhibit PFKFB3. The first report of screening, selection, and its impact on cancer cells was published by Clem et al. in 2013 [40]. An increase in binding potency of PFK15 was later achieved by the substitution of the pyridinyl ring with a quinoline ring in 3PO (

PFK15, a derivative of 3PO, was another chalcone compound developed to inhibit PFKFB3. The first report of screening, selection, and its impact on cancer cells was published by Clem et al. in 2013 [83]. An increase in binding potency of PFK15 was later achieved by the substitution of the pyridinyl ring with a quinoline ring in 3PO (Figure 9) [4]. This structural modification resulted in an increased selectivity and inhibitory effectiveness (~100-fold), which led to an enhancement of proapoptotic activity compared to 3PO [40]. Due to its modification, PFK15 shows better pharmacokinetic properties, e.g., reduced clearance, higher T1/2, and longer microsomal stability [40]. It was also reported that PFK15 did not inhibit other glycolysis-related enzymes such as phosphoglucose isomerase, PFK-1, PFKFB4, or hexokinase [40].

) [4]. This structural modification resulted in an increased selectivity and inhibitory effectiveness (~100-fold), which led to an enhancement of proapoptotic activity compared to 3PO [83]. Due to its modification, PFK15 shows better pharmacokinetic properties, e.g., reduced clearance, higher T1/2, and longer microsomal stability [83]. It was also reported that PFK15 did not inhibit other glycolysis-related enzymes such as phosphoglucose isomerase, PFK-1, PFKFB4, or hexokinase [83].PFK158, another novel PFKFB3 inhibitor, was proven effective in gynecological cancers [41] and mesothelioma [42]. Moreover, this compound was enrolled in a Phase I clinical trial in patients with advanced solid malignancies [43]. Clinical trials assessing the safety of PFK158 (NCT02044861) were initiated in 2014 and no serious adverse events were reported during the ~one-year follow-up [10]. Once the maximum tolerated dose has been established, Phase II trials of this optimized PFKFB3 inhibitor will also be introduced in leukemia therapy [40].

PFK158, another novel PFKFB3 inhibitor, was proven effective in gynecological cancers [82] and mesothelioma [149]. Moreover, this compound was enrolled in a Phase I clinical trial in patients with advanced solid malignancies [150]. Clinical trials assessing the safety of PFK158 (NCT02044861) were initiated in 2014 and no serious adverse events were reported during the ~one-year follow-up [10]. Once the maximum tolerated dose has been established, Phase II trials of this optimized PFKFB3 inhibitor will also be introduced in leukemia therapy [83].Since 2014, three novel inhibitors have been developed: compound 26 [44] and PQP [45] and KAN0438757 [46]. The anticancer efficacy was only proven in vitro. KAN0438757 is the most recently (2019) developed PFKFB3 inhibitor and may induce nucleotide incorporation during DNA repair and selectively sensitize transformed cells to the impact of radiation [46].

Since 2014, three novel inhibitors have been developed: compound 26 [151] and PQP [152] and KAN0438757 [153]. The anticancer efficacy was only proven in vitro. KAN0438757 is the most recently (2019) developed PFKFB3 inhibitor and may induce nucleotide incorporation during DNA repair and selectively sensitize transformed cells to the impact of radiation [153]. The recent progress in identifying new drugs targeting PFK-2 isozymes is dominated by compounds inhibiting PFKFB3. This is probably due to a better understanding of this isozyme and its role in cancer cell biology. To date, there has only been one study focusing on PFKFB4 inhibitor design, which reported an anti-proliferative effect of 5-(n-(8-methoxy-4-quinolyl)amino)pentyl nitrate (5MPN) on H460 adenocarcinoma cells. Clearly, these results were promising and justify further investigation of the effects of specific PFKFB4 inhibitors. The compounds described in this section have a diverse impact on cancer cell metabolism, which is the result of differences in their structures that determine the activity of each compound (IC50 or Ki) and translate into pharmacokinetic properties such as bioavailability and water solubility (Figure 2).

10).

Figure 210.

A

D

E

A)—N-Bromoacetylethanolamine phosphate [47], (

B)—3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one (3PO) [48], (

C)—PFK15 [49], (

D)—PFK158 [50], (

E)—5MPN [51]. The circles illustrate the differences in the chemical (green circles) and 3D structure (orange circles) between the 3PO (

B

C

D)–consecutive derivatives chalcone compounds. IC50 and Ki values were obtained from Wang et al. (2020) [4] and Chesney et al. (2015) [52].

3.2. Chemosensitivity, Chemoresistance, and Potential Combined Therapies for Malignancies

Current chemotherapeutic and irradiation protocols target rapidly dividing cells. Targeting glycolysis, a process that is regulated by PFKFB and is crucial for ATP generation in proliferating cancer cells seems to be a promising therapeutic approach with anticancer properties. Combining currently used chemotherapeutics (conventional or tumor pathway-specific agents) with PFKFB3 or PFKFB4 inhibitors is expected to enrich the range of treatment options. Despite the exponential development of new drugs, the occurrence of resistance simultaneously increases as well; this emphasizes the importance of implementing drug combinations or adding novel therapeutic agents in an attempt to overcome this hurdle [53]. PFKFB inhibition might prevent disease progression and drug resistance, and even improve progression-free survival (PFS) and/or response rates [10][30]. Another argument in favor of combination therapy with these inhibitors is the association between drug resistance, mitochondrial respiratory defects, and increased glycolysis in cancer cells [11][30][54]. Multiple trials verifying currently approved agents, such as inhibitors of angiogenesis or autophagy, and substances interfering with the electron transport chain or glutamine metabolism, in combination with PFKFB inhibitors are expected to be initiated in cohorts with distinct types of cancers [40]. Liu et al. (2001) suggested that the inhibition of glycolysis markedly sensitizes slow-growing cancers to chemotherapy and irradiation [55].

Current chemotherapeutic and irradiation protocols target rapidly dividing cells. Targeting glycolysis, a process that is regulated by PFKFB and is crucial for ATP generation in proliferating cancer cells seems to be a promising therapeutic approach with anticancer properties. Combining currently used chemotherapeutics (conventional or tumor pathway-specific agents) with PFKFB3 or PFKFB4 inhibitors is expected to enrich the range of treatment options. Despite the exponential development of new drugs, the occurrence of resistance simultaneously increases as well; this emphasizes the importance of implementing drug combinations or adding novel therapeutic agents in an attempt to overcome this hurdle [160]. PFKFB inhibition might prevent disease progression and drug resistance, and even improve progression-free survival (PFS) and/or response rates [10,32]. Another argument in favor of combination therapy with these inhibitors is the association between drug resistance, mitochondrial respiratory defects, and increased glycolysis in cancer cells [11,32,161]. Multiple trials verifying currently approved agents, such as inhibitors of angiogenesis or autophagy, and substances interfering with the electron transport chain or glutamine metabolism, in combination with PFKFB inhibitors are expected to be initiated in cohorts with distinct types of cancers [83]. Liu et al. (2001) suggested that the inhibition of glycolysis markedly sensitizes slow-growing cancers to chemotherapy and irradiation [162].