HAIC involves two procedures as follows: as scheduled, chemotherapeutic regimens are administered through a reservoir port connected to a catheter, which is implanted under the skin, and a catheter is inserted each time without implantation of the reservoir port. As HAIC is expected to accumulate drug concentrations in the local liver and reduce systemic toxicity of anti-cancer drugs, it is considered to have a more favorable antitumor effect and less influence on other organs than systemic chemotherapy. The clinical benefits of HAIC are as follows: (1) even a patient with Child–Pugh B HCC (7 or 8 points) is a candidate for HAIC (2) Child–Pugh scores barely decline with the use of HAIC compared with sorafenib (3) HAIC is highly effective in patients with vascular invasion compared with sorafenib; and (4) survival in patients receiving HAIC may not be associated with skeletal muscle volume. In contrast, the disadvantages are problems related with the reservoir system. HAIC has clinical benefits in a subpopulation of patients without extrahepatic metastasis with Child–Pugh A HCC and vascular invasion (especially primary branch invasion or main portal vein invasion) or with Child–Pugh B HCC.

- advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

- hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy

- sorafenib

- vascular invasion

1. Introduction

The introduction of sorafenib, a molecular-targeted agent (MTA), in 2007, has been a landmark in the history of systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). After the success of the SHARP and Asia-Pacific trials [1][2], several clinical trials of new MTAs (e.g., sunitinib, brivanib, and linifanib, among others) conducted from 2007 until 2016 have failed [3][4]. However, the recent success of treatments in clinical trials, such as regorafenib, lenvatinib, cabozantinib, and ramucirumab, has changed the treatment strategy for advanced HCC [5][6][7][8]. Furthermore, the combination of atezolizumab with bevacizumab improved overall and progression-free survival outcomes compared with sorafenib in patients with advanced HCC [9]. This combination therapy was approved for unresectable HCC in clinical practice in the United States (US) and Japan in May 2020 and September 2020, respectively. Therefore, combination therapy is likely considered the first-line therapy for advanced HCC, and current first-line MTAs (sorafenib and lenvatinib) and second-line MTAs (regorafenib, ramucirumab, and cabozantinib) are likely to be shifted to second- and third-line therapies, respectively [10]. However, as these above-mentioned drugs have been recommended to HCC patients with preserved liver, those with deteriorated liver function are generally not candidates for such drugs.

In contrast, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), which has been performed since the 1990s in Japan, may be a candidate for addressing an unmet medical need. Although several studies showed the efficacy of HAIC in a subpopulation of patients with advanced HCC [11][12][13][14][15][16][17], various guidelines from Asia, Europe, and the US do not recommend HAIC as a treatment option for advanced HCC due to low evidence levels, except for the Japanese guideline [18][19][20][21]. In addition, technical difficulties and medical care are needed to institute and maintain the reservoir system. Therefore, although HAIC has been used in East Asia, especially Japan, it has low feasibility as a treatment. Sorafenib has been widely used as a standard systemic therapeutic agent for more than 10 years, whereas adoption of HAIC has been limited. In this review, we discuss the current status and clinical benefits of HAIC for advanced HCC compared with sorafenib, based on articles published between 2008 and 2020.

2. Overview of HAIC

2.1. Concept

2.2. Regimens

As the anti-cancer drugs that can be used in HAIC differ across countries, it may be difficult to adopt these HAIC regimens. In Japan, three regimens have been used for HAIC treatment: 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) combined with low-dose cisplatin (CDDP) (low-dose FP) [22][23][24], 5-FU combined with interferon (FAIT) [25][26][27][28], and CDDP alone [29][30][31] (

Table 1.

| Authors [Reference] | Publishing Year | Regimens | Case Number | Vascular Invasion (%) | Response Rate (%) | Median Survival Time (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-dose FP | ||||||

| Saeki, et al. [22] | 2015 | Low-dose FP including the combination of LV/IV or IV plus IFN |

90 | ND | 34.4 | 10.6 |

| Nouso, et al. [23] | 2013 | CDDP+5FU | 476 | 44.1 | 40.5 | 14.0 (341 patients) |

| Ueshima, et al. [24] | 2010 | Low-dose FP | 52 | 80.8 | 38.5 | 15.9 |

| FAIT | ||||||

| Monden, et al. [25] | 2012 | IFNα, 5-FU | 34 | 90.0 | 26.7 | 8.4 |

| Low-dose FP/CDDP | 35 | 90.3 | 25.8 | 11.8 | ||

| Yamashita, et al. [26] | 2011 | IFNα, CDDP, 5-FU | 57 | 26.7 | 45.6 | 17.6 |

| IFNα, 5-FU | 57 | 50.0 | 24.6 | 10.5 | ||

| Nagano, et al. [27] | 2011 | IFNα, 5-FU | 102 | 100.0 | 39.2 | 9.0 |

| Obi, et al. [28] | 2006 | IFNα, 5-FU | 116 | 100.0 | 52.0 | 6.9 |

| CDDP | ||||||

| Ikeda, et al. [29] | 2013 | CDDP powder (IA call) | 25 | 100.0 | 28.0 | 7.6 |

| Kim, et al. [30] | 2011 | CDDP | 41 | 83.3 | 12.2 | 7.5 |

| CDDP, 5-FU | 97 | 27.8 | 12.0 | |||

| Yoshikawa, et al. [31] | 2008 | CDDP powder (IA call) | 80 | 27.5 | 33.8 | ND |

ND, not described; Low-dose FP, low-dose 5-fluorouracil plus cisplatin; LV, leucovorin; IV, isovorin; IFN, interferon; CDDP, cisplatin; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil.

2.3. Indications

HAIC is commonly used to treat advanced HCC, whether naive or recurrent tumors. According to the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (2017 version) established by the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH) [21], HAIC or MTA is recommended as a second-line treatment in HCC patients with ≥4 nodules, without vascular invasion and extrahepatic metastasis (EHM); whereas transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), hepatectomy, HAIC, and MTA are recommended as first-line treatments in HCC patients with vascular invasion, without EHM. Furthermore, patients with Child–Pugh A or B HCC are candidates for HAIC [21]. In this regard, the guidelines from Korea and Taiwan demonstrated that HAIC may be considered an optional treatment in a subpopulation of patients [33][34].

2.4. Clinical Outcomes

3. Clinical Benefits and Disadvantages of HAIC

The clinical benefits of HAIC for advanced HCC are as follows: (1) even a patient with Child–Pugh B HCC (7 or 8 points) is a candidate for HAIC [35], (2) Child–Pugh scores barely decline after HAIC [36][37], (3) HAIC is highly effective in patients with vascular invasion compared with sorafenib [11][38], and 4) survival in patients receiving HAIC may not be associated with skeletal muscle volume [39]. In contrast, the disadvantages of HAIC for advanced HCC are as follows: (1) a highly technical procedure is needed to implant a catheter with a reservoir port; (2) hospitalization is needed to continue HAIC treatments; (3) patients have to return for follow-up visits every 2 weeks to maintain the reservoir system; and (4) adverse events related to the reservoir system, such as port migration, catheter dislocation, arterial occlusion, reservoir system occlusion, subcutaneous hematomas, or infection [40].

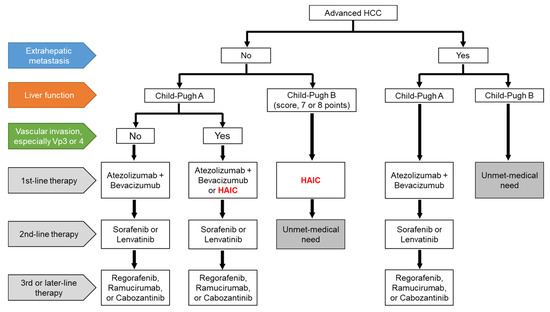

The clinical benefits of HAIC for advanced HCC are as follows: (1) even a patient with Child–Pugh B HCC (7 or 8 points) is a candidate for HAIC [43], (2) Child–Pugh scores barely decline after HAIC [42,44], (3) HAIC is highly effective in patients with vascular invasion compared with sorafenib [11,35], and 4) survival in patients receiving HAIC may not be associated with skeletal muscle volume [57]. In contrast, the disadvantages of HAIC for advanced HCC are as follows: (1) a highly technical procedure is needed to implant a catheter with a reservoir port; (2) hospitalization is needed to continue HAIC treatments; (3) patients have to return for follow-up visits every 2 weeks to maintain the reservoir system; and (4) adverse events related to the reservoir system, such as port migration, catheter dislocation, arterial occlusion, reservoir system occlusion, subcutaneous hematomas, or infection [65]. Atezolizumab combined with bevacizumab was recently approved, and this combination will be recommended as the first-line therapy for advanced HCC. However, a comparison between atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and HAIC has not been performed. Patients with macrovascular invasion, including an invasion of the main portal trunk, accounted for 38% of those in the atezolizumab plus bevacizumab group; however, the details were not shown [9]. Therefore, as there has been no information regarding this combination therapy in real-world practice, further studies are required. We present a draft of the treatment proposal for HAIC for advanced HCC inFigure 1. The combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab will be shifted to the first-line therapy in patients with Child–Pugh A HCC, regardless of EHM, and currently used MTAs will be shifted to later lines of therapy [10]. HAIC may be an optional treatment in patients with Child–Pugh A HCC and vascular invasion, especially Vp3 or Vp4, without EHM [11][38]. MTAs are generally used in patients with Child–Pugh A HCC, whereas the use of MTAs in patients with Child–Pugh B HCC remains controversial. Some Asian guidelines recommended that sorafenib is considered in selected patients with Child–Pugh B (e.g., score, 7 points) [18][33][34][41][42], although sorafenib treatment significantly worsened survival in patients with Child–Pugh B HCC compared to those with Child–Pugh A HCC [43]. In contrast, patients with Child–Pugh B HCC (score 7 or 8 points) are candidates for HAIC [35]. The medical needs of patients receiving second-line therapy for Child–Pugh B HCC without EHM and those who have EHM with Child–Pugh B HCC, are yet to be met. However, HAIC may be considered in a subpopulation of both Child–Pugh B HCC and EHM patients if the intrahepatic tumor is directly linked to prognosis. Therefore, patients in clinical trials who can tolerate deteriorated liver function would be candidates for the novel therapy [44][45]. We have reported the efficacy of arterial infusion of an iron chelator, deferoxamine, which is not an anti-cancer drug but is used for treating iron overload disease in advanced HCC patients, including Child–Pugh B or C patients [44]. However, deferasirox, an oral iron chelator, has limited efficacy due to associated adverse effects, especially renal dysfunction [45]. In the future, systemic therapeutic agents would be expected to be developed for the unmet medical needs of patients undergoing advanced HCC treatment.

. The combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab will be shifted to the first-line therapy in patients with Child–Pugh A HCC, regardless of EHM, and currently used MTAs will be shifted to later lines of therapy [10]. HAIC may be an optional treatment in patients with Child–Pugh A HCC and vascular invasion, especially Vp3 or Vp4, without EHM [11,35]. MTAs are generally used in patients with Child–Pugh A HCC, whereas the use of MTAs in patients with Child–Pugh B HCC remains controversial. Some Asian guidelines recommended that sorafenib is considered in selected patients with Child–Pugh B (e.g., score, 7 points) [18,33,34,66,67], although sorafenib treatment significantly worsened survival in patients with Child–Pugh B HCC compared to those with Child–Pugh A HCC [68]. In contrast, patients with Child–Pugh B HCC (score 7 or 8 points) are candidates for HAIC [43]. The medical needs of patients receiving second-line therapy for Child–Pugh B HCC without EHM and those who have EHM with Child–Pugh B HCC, are yet to be met. However, HAIC may be considered in a subpopulation of both Child–Pugh B HCC and EHM patients if the intrahepatic tumor is directly linked to prognosis. Therefore, patients in clinical trials who can tolerate deteriorated liver function would be candidates for the novel therapy [69,70]. We have reported the efficacy of arterial infusion of an iron chelator, deferoxamine, which is not an anti-cancer drug but is used for treating iron overload disease in advanced HCC patients, including Child–Pugh B or C patients [69]. However, deferasirox, an oral iron chelator, has limited efficacy due to associated adverse effects, especially renal dysfunction [70]. In the future, systemic therapeutic agents would be expected to be developed for the unmet medical needs of patients undergoing advanced HCC treatment.

Figure 1.