Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Kyoko Hida and Version 1 by Kyoko Hida.

Tumor progression relies on angiogenesis from established normal vasculature to form new tumor blood vessels. Tumor endothelial cells (TECs) in the tumor blood vessels maintain tumor vessel formation through continual angiogenesis. TECs are heterogeneous with a diverse cellular origin. Moreover, the various factors and conditions in the tumor microenvironment elicit specific characteristics in TECs differentiating them from endothelial cells in normal vessels. TECs are the main focus of antiangiogenesis strategies, and their unique features make tumor blood vessels good anti-cancer therapeutic targets.

- Tumor angiogenesis

- tumor endothelial cell

- antiangiogenic drugs

- tumor blood vessels

- antiangiogenic therapy

Tumor Vasculature

Tumors become vascularized through more than one mechanism of angiogenesis. It may take the form of sprouting angiogenesis [3] from preexisting vessels or the splitting of preexisting vessels into two daughter vessels by a process known as intussusception [4]. Neovascularization processes such as vasculogenesis mediated by endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) recruited from the bone marrow can lead to the development of tumor blood vessels [5]. In addition, through the process of vasculogenic mimicry, highly invasive and metastatic melanoma cells mimic the endothelium-forming ability of endothelial cells (ECs) and create loops or networks resembling the vasculature, which are devoid of ECs but contain blood cells [6]. These channels facilitate tumor blood supply independent of angiogenesis. Breast, colon, lung, pancreatic, ovarian, glioblastoma multiforme, and hepatocellular carcinomas are among the cancer types that present with vasculogenic mimicry [7].

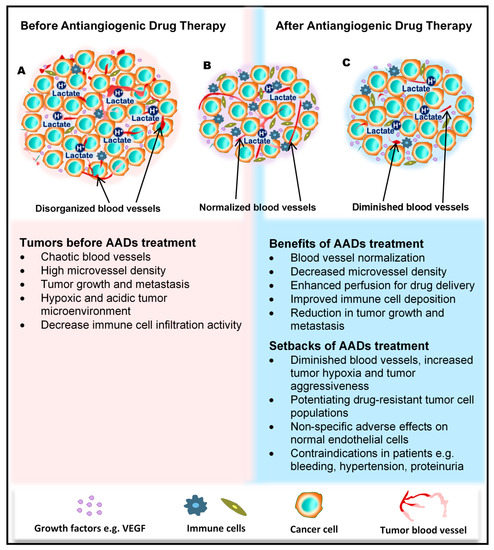

The tumor blood vessels carry nutrients to the tumor to stimulate rapid growth of the tumor, enrich the stroma with immune cells, and also aid tumor metastasis. In the wake of their development, tumors cause significant transformations in all cells and tissues in their surroundings. The growing tumor begins to exert physical pressure on the vessels, thus causing portions of the vessels to flatten and lose their lumen. Hierarchal vessel structure and blood flow are distorted (Figure 1A). Moreover, tumor-derived growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stimulate rapid angiogenesis without sufficient control from angiogenesis inhibitors, which leads to the formation of tortuous vessels with loose EC junctions [8], little or no perivascular cell coverage [9], and an overall leaky nature, further contributing to the high interstitial fluid pressure observed in tumors [10,11].

Figure 1. Benefits and side effects of antiangiogenic drugs. AADs, antiangiogenesis drugs. The dependency of tumors on their resident blood vessels to grow and metastasize has led to the targeting of tumor blood vessels to starve the tumor cells and close the metastasis portals. (A) Before the administration of AADs, the tumor histology is characterized by a high density of microvessels, with an undefined order of organization. The microenvironment is generally acidic, with high lactate levels, and immunologically suppressed. (B) However, after AAD therapy, tumor blood vessels become normalized, microvessel number reduces, tumor growth recedes, and immune cells infiltrate the tumors more through the normalized vasculature. (C) In addition to these benefits, AAD use causes some undesirable effects, including tumor hypoxia (from prolonged use of AADs) and destruction of normal vessels leading to bleeding. Patients may also experience hypertension and proteinuria, among others.

Angiogenesis and Its Inhibition in Tumors

Angiogenesis

Sprouting angiogenesis is the physiological process that was described as the formation of new blood vessels by capillary sprouting from preexisting vessels. Most blood vessels remain quiescent in the adult body, and angiogenesis occurs only in female reproductive organs and in the placenta during pregnancy. However, ECs preserve the function of rapid division in response to a physiological stimulus such as hypoxia or inflammation [12]. Angiogenic factors such as VEGF, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), angiopoietin, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) drive angiogenesis, and it is also performed as a normal process in growth and developmental processes, such as wound healing [13,14].

Factors That Stimulate and Regulate Tumor Angiogenesis

The tumor uses existing angiogenic mechanisms to induce capillary growth. Various growth factors, including VEGF, bFGF, PDGF, and angiopoietin, can induce tumor angiogenesis [15]. These factors are secreted from tumor cells and stromal cells. For example, tumors activate tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) or neutrophils to produce angiogenic factors such as VEGF and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [16,17]. Furthermore, other immune cell types indirectly influence the process of angiogenesis through the secretion of VEGF-A, bFGF, MMP9, interferon gamma (IFNγ), and interleukin-17 (IL-17) [18,19,20]. These angiogenesis stimuli may also be triggered by metabolic stress such as hypoxia, low pH or hypoglycemia, mechanical stress and genetic mutations, and p53 regulation [21,22,23,24].

Concept of Antiangiogenic Therapy and Development of Angiogenesis Drugs and Their Molecular Targets

For a long period of time, cytotoxic drugs were conventionally used for anticancer treatment. Later on, antiangiogenic therapy was proposed as a new concept for anticancer treatment. Dr. Judah Folkman in the early 1970s proposed that cancer could be treated by blocking the supply of oxygen and nutrients through the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis [25]. Moreover, antiangiogenic therapy has the potential to normalize blood vessel structures and improve systemic delivery of oxygen or perfusion of cytotoxic drugs into tumor tissues (Figure 1B) [26,27].

Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF, was first approved as an antiangiogenic therapy in 2004 for the treatment of colon cancer in combination with chemotherapy [28,29]. Since then, various antiangiogenesis drugs, either as monotherapy or in combination with other cytotoxic drugs, have been developed, used in clinical trials, and approved for the treatment of cancer. The antiangiogenesis drugs include tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as sorafenib, sunitinib, axitinib, and pazopanib target receptors for VEGF and PDGF to inhibit the VEGF pathway [30]. By targeting their receptors expressed on tumor endothelial cells (TECs), these angiogenesis drugs are able to inhibit tumor angiogenesis.

Besides VEGF and its receptors, several other growth factors and receptors are involved in pathways that regulate tumor growth and angiogenesis in a complementary and coordinated manner. New multikinase inhibitors that can simultaneously target more than one of these pathways have been developed and approved for anticancer treatment. For example, regorafenib was found to inhibit a distinct set of receptor kinases, including the vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR1–3), TIE2, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1), and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFR-b), and has been approved for treating hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors [31,32,33,34]. Cabozantinib was found to inhibit VEGFR2, c-Met, and AXL receptor tyrosine kinases and has been approved for treating metastatic renal cell carcinoma [35,36]. Several other multikinase inhibitors have also been developed and used in clinical trials or clinical settings [37]. The mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is also involved in angiogenesis, and mTOR inhibitors such as everolimus and temsirolimus have been approved for clinical use [38].

Positive Achievements and Clinical Outcomes of Antiangiogenic Therapy

Antiangiogenic therapy enhances T-cell priming and activation by promoting dendritic cell maturation and increasing T-cell infiltration into the tumor tissue via tumor vessel normalization [39,40,41]. Antiangiogenic therapy also converts an immune-permissive tumor microenvironment by decreasing regulatory T-cell and myeloid-derived suppressor cells [41,42]. Tumor vessel normalization is crucial for improving the immune environment, tumor immunity is the key factor for anticancer treatment, and improving the immune environment is necessary to increase treatment efficacy (Figure 1B). Today, immune checkpoint inhibitors have been approved for treating various cancers [43,44,45]; furthermore, recent therapeutic strategies target both tumor angiogenesis and tumor immunity for achieving a greater therapeutic effect. As a combination therapy, bevacizumab and IFNα have been approved for treating metastatic renal cell carcinoma [46]. Clinical trials of combined TKIs and immune checkpoint inhibitors are actively being conducted, and favorable outcomes have been observed in metastatic renal cell carcinoma and non-small cell lung cancer [47,48,49,50].

Negative Side Effects/Adverse Responses from Patients

Regardless of the enormous benefits, antiangiogenic therapy has several problems. Complications such as hypertension, hand–foot syndrome, proteinuria, and thyroid dysfunction could occur as adverse events because of the effect of antiangiogenesis drugs on normal blood vessels [51]. Drug resistance to antiangiogenic therapy may also occur, and drug switching is generally required. Various mechanisms are described for explaining the resistance to antiangiogenic therapy, and various cellular and noncellular factors in the tumor microenvironment such as TECs, immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, or extracellular matrix components are involved in these resistance mechanisms [52,53]. Long-term antiangiogenic therapy leads to tumor hypoxia and induces tumor aggressive behavior [54] (Figure 1C). It has been reported that hypoxia promotes the accumulation of TAMs [55] and induces tumor angiogenesis through the mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial precursor cells [56]. Hypoxia also induces chromosomal abnormalities in TECs via reactive oxygen species [57] and the selection of more invasive metastatic populations of tumor cells that are resistant to antiangiogenic therapy [58] (Figure 1C). Other modes of tumor vascularization such as vascular mimicry and vessel co-option have been suggested as another mechanism underlying the resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. Vascular mimicry is a tumor blood supply system without the participation of ECs. Vascular-like constructions are generated through the differentiation of tumor cells into endothelial-like cells, independent of conventional angiogenic factors [6]. An increase in vascular mimicry has been observed after antiangiogenic therapy [59]. Vessel co-option occurs in metastatic tumors. Tumor cells co-opt and grow around existing blood vessels [60]. Vessel co-option could explain the cause of resistance to antiangiogenic therapy in various cancers [61,62,63].

Tissue and Cellular Sources of TECs

Blood Vessels

The key players in the formation of blood vessels and the likely target of antiangiogenic therapy, ECs, through the process of sprouting angiogenesis, migrate and proliferate to form vessels by relying on cues from the growing tumor. Like the vessels recruited into the tumor, the ECs are similarly imparted by the growing tumor themselves as well as the microenvironmental factors, leading to the development of unique characteristics in these recruited ECs different from those of normal endothelial cells (NECs). These endothelial cells, often designated as TECs or tumor-associated ECs, have their primary origin as the blood vessels within the tumor mass. TECs have been isolated from various tumors, and analyses have shown that they indeed have an endothelial lineage [64]; however, some studies have demonstrated that other cellular sources of the tumor endothelium exist.

Cancer Stem Cells and EPCs

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) and EPCs are involved in this nonconventional tumor vasculature formation through vasculogenesis. ECs in glioblastoma were found to have similar genetic alterations as those in the tumor cells; moreover, glioblastoma stem cells positive for the stem cell marker CD133 were capable of generating cells that phenotypically and functionally resembled ECs [65,66]. Contrary to the above suggestions that TECs could arise from cancer stem cells, some recent reports have demonstrated that it is rather rare to find ECs with neoplastic origins within the glioblastoma vasculature. Kulla et al. reported that glomeruloid vessels microdissected from glioblastoma tissue specimens lacked mutations in the tumor protein p53 (TP53) gene as compared to the surrounding glioblastoma cells with a mutation in 3 exons of this gene [67]. Additionally, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene amplification could not be identified in CD34+ endothelial cells within the vascular linings of glioblastoma tissue, further supporting the unlikely contribution of glioblastoma cells to tumor vessel formation [68]. However, glioma stem cells may contribute to tumor angiogenesis by differentiating into perivascular cells, like pericytes, not endothelial cells, which are necessary for blood vessel maturation [69]

EPCs originate as progenitor cells from the bone marrow possessing the ability to develop into matured ECs. As EPCs travel from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood to the tumors, their surface molecules change from CD133+/CD34+/VEGFR2+ cells to cells with a decreased expression of CD133, while maintaining the expression of VEGFR2 and the hematopoietic progenitor cell antigen CD34 as they mature in circulation. The matured ECs in the vessels finally lose both CD133 and CD34 but display high VEGFR2 expression and are positive for vascular endothelial cadherin, von Willebrand factor, and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM1), also known as CD31 [70]. EPCs are known to both support vessel formation and integrate directly into the endothelium. Early-forming EPCs secrete angiogenic growth factors and cytokines (e.g., VEGF, stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and IL-8 [71]) to facilitate neovascularization, whereas late-forming EPCs were found to be better at forming capillary tubes and could differentiate easily into ECs [72]. Both tumor-derived growth factors and EPC-secreted molecules play a role in recruiting EPCs into peripheral circulation and further into the tumor tissue to initiate tumor vasculogenesis. The abundance of EPCs in various types of cancers, including breast cancer [73], non-small cell lung cancer [74], hepatocellular carcinoma [75], colorectal cancer, leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma [76], and glioma [65,66], indicates their relevance in the tumor growth [77]. The role of EPCs in enhancing microvessel formation within some of these tumors has been demonstrated. Therefore, EPCs are an established source of TECs.

TEC Characteristics

Cytogenetic Abnormality

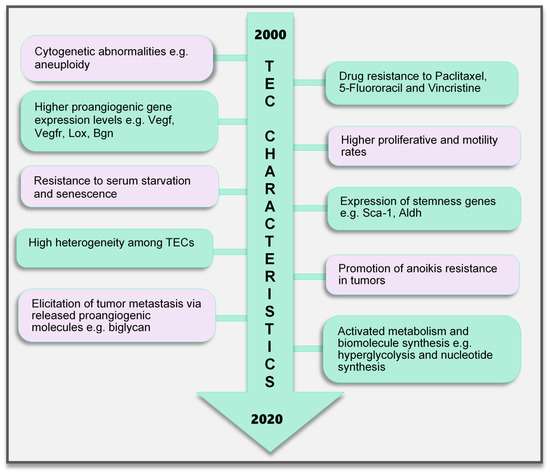

Contrary to earlier assumptions about TECs, it has been shown for over a decade that TECs are undoubtedly different from NECs. TECs have characteristics that are considered to be abnormal, ranging from their morphology to genetics and function (Figure 2). TECs obtained from human melanoma and liposarcoma tumor xenografts structurally possessed bigger nuclei with different size variations than those in NECs [78]. These nuclei were made up of chromosomes with various structural aberrations, translocations, chromosomal aneuploidy, missing chromosomes, and the presence of additional chromosomes such as double minutes and some of unknown origin [78]. Microvascular ECs in B-cell lymphoma were also found to have lympho-specific chromosomal translocations [79]. More recently, nonhematopoietic aneuploid CD31+ circulating TECs were detected in the peripheral blood of patients with breast cancer, demonstrating that circulating TECs, and not only tumor-bound TECs, possess chromosomal changes [80]. Due to these changes, TECs obtained from human [81] and murine tumors [78] are genetically unstable compared with NECs. We have reported that the TECs isolated from xenograft human epithelial tumors, which were CD133(+), were susceptible to a higher frequency of aneuploidy than the CD133(-) TECs. This suggests that progenitor cells do not only contribute to TEC generation but may also be involved in inducing genetic instability in these cells [81]. Other causes of TEC aneuploidy include hypoxia-induced reactive oxygen species and VEGF signaling [57]. It has been reported that VEGF signaling also regulates the centrosome duplication cycle in ECs and induces centrosome overduplication [82], which could further lead to aneuploidy [83]. Stromal cells like fibroblasts and ECs receive tumor genetic material (DNA/chromosomes) transferred via apoptotic bodies from tumor cells [84,85]. Such horizontal gene transfer can lead to cytogenetic alterations in ECs. Furthermore, genetic instabilities could occur within the cells through the propagation of the DNA. Replication of the transferred DNA may occur in the recipient cells provided they have undergone certain changes including p21 and p53 inactivation [84,85,86].

Figure 2. TEC characteristics identified to date. Various characteristics of TECs have been observed, which make them unique when compared with endothelial cells in normal blood vessels. These range from the genetic composition and expression of genes, abnormal karyotype, higher biological activities (proliferation and motility), and TEC influence on tumor cells to modulate cancer cell metastasis and survival to modifications in their metabolic signature. TECs are not normal and their abnormality creates a targetable avenue to influence the growth of tumors and improve therapeutics in cancer treatment. TEC, tumor endothelial cells

Genotypic Changes

In addition, genes regulating angiogenesis, cell proliferation and motility, stemness, and drug resistance, among others, are altered in TECs. ECs require the autocrine function of VEGF to sustain vascular integrity and viability [87]. VEGF acts through its receptors, the VEGFRs. Among them, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 have been shown to be highly expressed in TECs compared to those in NECs. This enhances the response of TECs to VEGF more than NECs [88], which makes TECs proangiogenic and may also support their ability to survive in serum-free media unlike their normal counterparts [89]. Furthermore, TECs proliferate and migrate faster than NECs [88]. A study comparing ECs isolated from colorectal cancer and normal colorectal mucosa demonstrated the unique expression of 46 genes in the tumor endothelium (i.e., TECs) as opposed to the normal endothelium [90]. The top 25 genes included MMP2 and MMP11, as well as variations of collagen types I, III, and VI, among others. The authors of that study described these genes as tumor endothelial markers (TEMs) by confirming through the analysis of TEM7 expression in the lung, pancreas, breast, and brain and suggested that the TEMs may be expressed in other cancers as well [90]. These findings established a promising future for the use of the TEMs in further research to identify novel antiangiogenesis strategies. However, later publications suggested that not all the TEMs are unique to TECs. TEM1, TEM 5, TEM7, and TEM 8 were found to be also expressed in normal cells, tissues, and organs [91,92,93,94]. The secreted and membrane forms of TEM7 were observed in various osteogenic sarcoma cell lines [95]. TEC heterogeneity is a major factor contributing to the genotypic differences observed between NECs and TECs. TECs obtained from low-metastatic and high-metastatic tumors have different tendencies toward cell proliferation, motility, and drug resistance, indicating that there may be differences in the underlying genotype of these cells. We had demonstrated that genes required for angiogenesis-related molecules and matrix-degrading enzymes were upregulated in the TECs obtained from highly metastatic tumors [96]. Moreover, the heterogeneity arising from the different cellular origin (stems cells, cancers, and EPCs) of TECs may account for the different genotype of TECs compared with NECs [97]. TECs isolated from different tumor types show variations in their gene expression profiles, the upregulated gene, or the gene set classification. ADAM23, FAP, GPNMB, and PRSS3 genes were high in ovarian cancer ECs [98], while G-protein-coupled receptor RDC1 was the distinctively induced TEM in TECs of the brain and the peripheral vasculature [99]. Furthermore, fewer similarities exist between different TEC gene profiles. A collation of 73 TEC marker genes from five studies showed that at most, only two cancer types shared one of these five genes (EGFL6, HEYL, MMP9, SPARC, PLXDC1), and the rest were expressed uniquely in only one cancer [100]. Aird reviewed that TEC gene expression heterogeneity is influenced by the tumor type, extracellular environment, and epigenetic regulation [100]; however, the current vast database needs to be sifted through by further research to obtain significant translational benefits.

Drug Resistance and Anoikis Resistance

A drug resistance phenotype has been reported in various TECs. The TECs isolated from A375SM (super-metastatic human melanoma cells) xenografts are resistant to the anticancer drug paclitaxel [101], and CD105+ TECs isolated from hepatocellular carcinoma were found to be resistant to doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil [102]. TEC resistance to paclitaxel was attributed to the upregulated expression of multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1) mRNA through VEGF signaling [101]. The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily, which includes ABCB1 (i.e., MDR1/P-glycoprotein, P-gp), is expressed in CSCs [103]. TECs may possess stemness properties as they express MDR1 and other stemness markers such as aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), CD90, and stem cell antigen-1 (Sca-1) [104]. These stem cell features of TECs suggest the versatility in their function and continuous availability.

The survival and function of TECs in the tumor microenvironment can be promoted by the expression of microRNAs (miR-145), which confers on the cells the ability to resist anoikis and become more adhesive by activating ERK1/2 and epigenetic modifications to enhance miR-145 expression [105]. Circulating tumor-associated ECs that express Bcl-2 have been implicated in protecting tumor cells from anoikis and enhancing lung metastasis. For TECs to protect tumor cells in circulation, they should also possess the ability to survive in circulation [106]. Although the study did not address anoikis resistance in TECs, the authors showed that TECs exhibited increased adhesive properties and were Bcl-2-positive, which was similar to the effect of miR145 on anoikis-resistant TECs in our study. Bcl-2 upregulation has been shown to enhance EC survival [107]. These findings may imply that anoikis-resistant TECs could promote tumor metastasis. In fact, we have demonstrated that TECs can elicit metastasis of low-metastatic tumors to the lung by releasing the angiocrine factor biglycan [108].

Altered Metabolism

EC metabolism plays a crucial role in the formation of blood vessels. In general, most of the known metabolic–biosynthetic pathways are more activated in TECs than in NECs [109]. Glycolysis regulates the migration and proliferation of tip and stalk ECs, respectively, through the activity of the glycolytic enzyme phosphofructokinase-2/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) [110]. Although normal healthy ECs were shown to have a higher glycolytic level than other healthy cells [110], we and other groups have demonstrated that glycolysis is more activated in TECs [111], conferring on these cells the “hyperglycolytic” label [112,113]. In these hyperglycolytic TECs, PFKFB3 and other glycolytic enzymes are upregulated compared to those in their normal counterparts. Inhibition of PFKFB3 in ECs decreased tumor metastasis by inducing the normalization of the tumor vessels. The vessel structure was improved from a disorganized structure to more matured pericyte-covered, perfused vessels, which supported better drug delivery leading to antimetastatic therapeutic benefits [112]. In addition, cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) supports the upregulated expression of PFKFB3 and VEGF in TECs to facilitate the higher glycolytic rates in these cells [113]. This role of COX2 in TEC glycolysis may partly explain our previous discovery that COX2 is essential for tumor angiogenesis. We found that COX2 was upregulated in TECs and its inhibition decreased the tumor growth and the recruitment of vascular progenitor cells into tumor vessels. COX2 inhibition further reduced the migration and proliferation of TECs, implying that both the angiogenic activity of resident TECs in the tumor and the recruitment of progenitor cells that can become TECs are impaired by COX2 [114]. The hyperglycolytic nature of TECs may potentially contribute to the overwhelming lactate burden within the tumor and exert various effects on stromal cells. It is interesting to note that somehow TECs survive in these high-lactate environments, and angiogenesis is not impaired. We have reported that in addition to the enzymes that directly influence substrate metabolism, enzymes that maintain intracellular pH at physiological levels significantly influence TEC proliferation. TECs release more lactate extracellularly than NECs, accompanied by an acidification of the culture media. Notably, these TECs displayed an upregulated expression of the pH regulatory enzyme carbonic anhydrase 2 (CAII). CAII in TECs was required for successful proliferation, independent of the metabolic substrate available [111]. Moreover, to maintain their higher proliferative rates, TECs require nucleotide precursors and lipids from serine and lipid biosynthesis pathways, respectively. To support this demand for biomolecules, TECs express higher levels of key pathway enzymes such as D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) and phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1) [112] for serine biosynthesis and fatty acid synthase (FASN) [115] for lipid synthesis. Nucleotide biosynthesis is also enhanced in TECs compared to that in NECs [109]. TECs are a robust group of cells that deserve special attention and study in the pursuit of direct, effective tumor angiogenesis therapeutic strategies.

- Ribatti, D.; Crivellato, E. “Sprouting angiogenesis”, a reappraisal. Dev. Biol. 2012, 372, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianni-Barrera, R.; Trani, M.; Reginato, S.; Banfi, A. To sprout or to split? VEGF, Notch and vascular morphogenesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 1644–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcola, M.; Rodrigues, C.E. Endothelial progenitor cells in tumor angiogenesis: Another brick in the wall. Stem Cells Int. 2015, 2015, 832649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniotis, A.J.; Folberg, R.; Hess, A.; Seftor, E.A.; Gardner, L.M.; Pe’er, J.; Trent, J.M.; Meltzer, P.S.; Hendrix, M.J. Vascular channel formation by human melanoma cells in vivo and in vitro: Vasculogenic mimicry. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 155, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Cortes, M.; Delgado-Bellido, D.; Oliver, F.J. Vasculogenic Mimicry: Become an Endothelial Cell “But Not So Much”. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashizume, H.; Baluk, P.; Morikawa, S.; McLean, J.W.; Thurston, G.; Roberge, S.; Jain, R.K.; McDonald, D.M. Openings between defective endothelial cells explain tumor vessel leakiness. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 156, 1363–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, S.; Baluk, P.; Kaidoh, T.; Haskell, A.; Jain, R.K.; McDonald, D.M. Abnormalities in pericytes on blood vessels and endothelial sprouts in tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 160, 985–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, H.F. Rous-Whipple Award Lecture. How tumors make bad blood vessels and stroma. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 162, 1747–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldin, C.-H.; Rubin, K.; Pietras, K.; Östman, A. High interstitial fluid pressure—an obstacle in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeliet, P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature 2005, 438, 932–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.W.; Cachianes, G.; Kuang, W.J.; Goeddel, D.V.; Ferrara, N. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science 1989, 246, 1306–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeliet, P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P.; Jain, R.K. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature 2000, 407, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Buranych, A.; Sarkar, D.; Fisher, P.B.; Wang, X.Y. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor vascularization. Vasc. Cell 2013, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Ferrara, N. The Complex Role of Neutrophils in Tumor Angiogenesis and Metastasis. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, T.; Kudo, M. Signaling pathways governing tumor angiogenesis. Oncology 2011, 81 (Suppl. 1), 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numasaki, M.; Fukushi, J.; Ono, M.; Narula, S.K.; Zavodny, P.J.; Kudo, T.; Robbins, P.D.; Tahara, H.; Lotze, M.T. Interleukin-17 promotes angiogenesis and tumor growth. Blood 2003, 101, 2620–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, S.M.; Cheresh, D.A. Tumor angiogenesis: Molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P. Developmental biology. Controlling the cellular brakes. Nature 1999, 401, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerbel, R.S. Tumor angiogenesis: Past, present and the near future. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi, R.; Mookerjee, B.; Bhujwalla, Z.M.; Sutter, C.H.; Artemov, D.; Zeng, Q.; Dillehay, L.E.; Madan, A.; Semenza, G.L.; Bedi, A. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by p53-induced degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farhang Ghahremani, M.; Goossens, S.; Nittner, D.; Bisteau, X.; Bartunkova, S.; Zwolinska, A.; Hulpiau, P.; Haigh, K.; Haenebalcke, L.; Drogat, B.; et al. p53 promotes VEGF expression and angiogenesis in the absence of an intact p21-Rb pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2013, 20, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, J. Anti-angiogenesis: New concept for therapy of solid tumors. Ann. Surg. 1972, 175, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.K. Normalizing tumor vasculature with anti-angiogenic therapy: A new paradigm for combination therapy. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 987–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.K. Normalization of tumor vasculature: An emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science 2005, 307, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, N.; Hillan, K.J.; Gerber, H.P.; Novotny, W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Novotny, W.; Cartwright, T.; Hainsworth, J.; Heim, W.; Berlin, J.; Baron, A.; Griffing, S.; Holmgren, E.; et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2335–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.T.; Haap, M.; Kopp, H.G.; Lipp, H.P. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors—A review on pharmacology, metabolism and side effects. Curr. Drug Metab. 2009, 10, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.M.; Dumas, J.; Adnane, L.; Lynch, M.; Carter, C.A.; Schutz, G.; Thierauch, K.H.; Zopf, D. Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506): A new oral multikinase inhibitor of angiogenic, stromal and oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases with potent preclinical antitumor activity. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruix, J.; Qin, S.; Merle, P.; Granito, A.; Huang, Y.H.; Bodoky, G.; Pracht, M.; Yokosuka, O.; Rosmorduc, O.; Breder, V.; et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothey, A.; Van Cutsem, E.; Sobrero, A.; Siena, S.; Falcone, A.; Ychou, M.; Humblet, Y.; Bouche, O.; Mineur, L.; Barone, C.; et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): An international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetri, G.D.; Reichardt, P.; Kang, Y.K.; Blay, J.Y.; Rutkowski, P.; Gelderblom, H.; Hohenberger, P.; Leahy, M.; von Mehren, M.; Joensuu, H.; et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): An international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakes, F.M.; Chen, J.; Tan, J.; Yamaguchi, K.; Shi, Y.; Yu, P.; Qian, F.; Chu, F.; Bentzien, F.; Cancilla, B.; et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 10, 2298–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Halabi, S.; Sanford, B.L.; Hahn, O.; Michaelson, M.D.; Walsh, M.K.; Feldman, D.R.; Olencki, T.; Picus, J.; Small, E.J.; et al. Cabozantinib Versus Sunitinib As Initial Targeted Therapy for Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma of Poor or Intermediate Risk: The Alliance A031203 CABOSUN Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaszai, J.; Schmidt, M.H.H. Trends and Challenges in Tumor Anti-Angiogenic Therapies. Cells 2019, 8, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meric-Bernstam, F.; Mills, G.B. Mammalian target of rapamycin. Semin. Oncol. 2004, 31, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrilovich, D.I.; Chen, H.L.; Girgis, K.R.; Cunningham, H.T.; Meny, G.M.; Nadaf, S.; Kavanaugh, D.; Carbone, D.P. Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T.; Ran, S.; Ishida, T.; Nadaf, S.; Kerr, L.; Carbone, D.P.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Vascular endothelial growth factor affects dendritic cell maturation through the inhibition of nuclear factor-kappa B activation in hemopoietic progenitor cells. J. Immunol. 1998, 160, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Wallin, J.J.; Bendell, J.C.; Funke, R.; Sznol, M.; Korski, K.; Jones, S.; Hernandez, G.; Mier, J.; He, X.; Hodi, F.S.; et al. Atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab enhances antigen-specific T-cell migration in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, P.S.; Wallin, J.J.; Mancao, C. Predictive markers of anti-VEGF and emerging role of angiogenesis inhibitors as immunotherapeutics. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 52, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.S.; Brahmer, J.R.; Gettinger, S.N.; Smith, D.C.; McDermott, D.F.; Powderly, J.D.; Carvajal, R.D.; Sosman, J.A.; Atkins, M.B.; et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Tykodi, S.S.; Chow, L.Q.; Hwu, W.J.; Topalian, S.L.; Hwu, P.; Drake, C.G.; Camacho, L.H.; Kauh, J.; Odunsi, K.; et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2455–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennock, G.K.; Chow, L.Q. The Evolving Role of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Treatment. Oncologist 2015, 20, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escudier, B.; Cosaert, J.; Jethwa, S. Targeted therapies in the management of renal cell carcinoma: Role of bevacizumab. Biologics 2008, 2, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, B.I.; Powles, T.; Atkins, M.B.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; Suarez, C.; Bracarda, S.; Stadler, W.M.; Donskov, F.; Lee, J.L.; et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (IMmotion151): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 2404–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Mok, T.S.K.; Nishio, M.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodriguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower150): Key subgroup analyses of patients with EGFR mutations or baseline liver metastases in a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Penkov, K.; Haanen, J.; Rini, B.; Albiges, L.; Campbell, M.T.; Venugopal, B.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Negrier, S.; Uemura, M.; et al. Avelumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulieres, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacche, R.N.; Meshram, R.J. Angiogenic factors as potential drug target: Efficacy and limitations of anti-angiogenic therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1846, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergers, G.; Hanahan, D. Modes of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huijbers, E.J.; van Beijnum, J.R.; Thijssen, V.L.; Sabrkhany, S.; Nowak-Sliwinska, P.; Griffioen, A.W. Role of the tumor stroma in resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Drug Resist. Update 2016, 25, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pàez-Ribes, M.; Allen, E.; Hudock, J.; Takeda, T.; Okuyama, H.; Viñals, F.; Inoue, M.; Bergers, G.; Hanahan, D.; Casanovas, O. Antiangiogenic Therapy Elicits Malignant Progression of Tumors to Increased Local Invasion and Distant Metastasis. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanmee, T.; Ontong, P.; Konno, K.; Itano, N. Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers 2014, 6, 1670–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.; Nolan, D.; McDonnell, K.; Vahdat, L.; Benezra, R.; Altorki, N.; Mittal, V. Bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells contribute to the angiogenic switch in tumor growth and metastatic progression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1796, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondoh, M.; Ohga, N.; Akiyama, K.; Hida, Y.; Maishi, N.; Towfik, A.M.; Inoue, N.; Shindoh, M.; Hida, K. Hypoxia-induced reactive oxygen species cause chromosomal abnormalities in endothelial cells in the tumor microenvironment. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factors: Mediators of cancer progression and targets for cancer therapy. Trends. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 33, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, X.Y.; Yang, Q.Y.; Xu, W.W.; Liu, G.L. Short-term anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment elicits vasculogenic mimicry formation of tumors to accelerate metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 31, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holash, J.; Maisonpierre, P.C.; Compton, D.; Boland, P.; Alexander, C.R.; Zagzag, D.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Wiegand, S.J. Vessel cooption, regression, and growth in tumors mediated by angiopoietins and VEGF. Science 1999, 284, 1994–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frentzas, S.; Simoneau, E.; Bridgeman, V.L.; Vermeulen, P.B.; Foo, S.; Kostaras, E.; Nathan, M.; Wotherspoon, A.; Gao, Z.H.; Shi, Y.; et al. Vessel co-option mediates resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy in liver metastases. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuczynski, E.A.; Yin, M.; Bar-Zion, A.; Lee, C.R.; Butz, H.; Man, S.; Daley, F.; Vermeulen, P.B.; Yousef, G.M.; Foster, F.S.; et al. Co-option of Liver Vessels and Not Sprouting Angiogenesis Drives Acquired Sorafenib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgeman, V.L.; Vermeulen, P.B.; Foo, S.; Bilecz, A.; Daley, F.; Kostaras, E.; Nathan, M.R.; Wan, E.; Frentzas, S.; Schweiger, T.; et al. Vessel co-option is common in human lung metastases and mediates resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy in preclinical lung metastasis models. J. Pathol. 2017, 241, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naschberger, E.; Schellerer, V.S.; Rau, T.T.; Croner, R.S.; Sturzl, M. Isolation of endothelial cells from human tumors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 731, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Chadalavada, K.; Wilshire, J.; Kowalik, U.; Hovinga, K.E.; Geber, A.; Fligelman, B.; Leversha, M.; Brennan, C.; Tabar, V. Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour endothelium. Nature 2010, 468, 829–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci-Vitiani, L.; Pallini, R.; Biffoni, M.; Todaro, M.; Invernici, G.; Cenci, T.; Maira, G.; Parati, E.A.; Stassi, G.; Larocca, L.M.; et al. Tumour vascularization via endothelial differentiation of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Nature 2010, 468, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulla, A.; Burkhardt, K.; Meyer-Puttlitz, B.; Teesalu, T.; Asser, T.; Wiestler, O.D.; Becker, A.J. Analysis of the TP53 gene in laser-microdissected glioblastoma vasculature. Acta Neuropathol. 2003, 105, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, F.J.; Orr, B.A.; Ligon, K.L.; Eberhart, C.G. Neoplastic cells are a rare component in human glioblastoma microvasculature. Oncotarget 2012, 3, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Q.; Donnola, S.; Liu, J.K.; Fang, X.; Sloan, A.E.; Mao, Y.; Lathia, J.D.; et al. Glioblastoma stem cells generate vascular pericytes to support vessel function and tumor growth. Cell 2013, 153, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, M.; Erl, W.; Weber, P.C. Endothelial progenitor cells: Isolation and characterization. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2003, 13, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbich, C.; Aicher, A.; Heeschen, C.; Dernbach, E.; Hofmann, W.K.; Zeiher, A.M.; Dimmeler, S. Soluble factors released by endothelial progenitor cells promote migration of endothelial cells and cardiac resident progenitor cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005, 39, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.; Yoon, C.H.; Kim, H.S.; Choi, J.H.; Kang, H.J.; Hwang, K.K.; Oh, B.H.; Lee, M.M.; Park, Y.B. Characterization of two types of endothelial progenitor cells and their different contributions to neovasculogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirakawa, K.; Furuhata, S.; Watanabe, I.; Hayase, H.; Shimizu, A.; Ikarashi, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Terada, M.; Hashimoto, D.; Wakasugi, H. Induction of vasculogenesis in breast cancer models. Br. J. Cancer 2002, 87, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilbe, W.; Dirnhofer, S.; Oberwasserlechner, F.; Schmid, T.; Gunsilius, E.; Hilbe, G.; Wöll, E.; Kähler, C.M. CD133 positive endothelial progenitor cells contribute to the tumour vasculature in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 2004, 57, 965–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.-T.; Yuan, X.-W.; Zhu, H.-T.; Deng, Z.-M.; Yu, D.-C.; Zhou, X.; Ding, Y.-T. Endothelial precursor cells promote angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 4925–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, A.; Melaccio, A.; Lamanuzzi, A.; Saltarella, I.; Dammacco, F.; Vacca, A.; Ria, R. Functional and Biological Role of Endothelial Precursor Cells in Tumour Progression: A New Potential Therapeutic Target in Haematological Malignancies. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 7954580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, H.-Q.; Li, J.; Liu, X.-L. Endothelial progenitor cells promote tumor growth and progression by enhancing new vessel formation. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hida, K.; Hida, Y.; Amin, D.N.; Flint, A.F.; Panigrahy, D.; Morton, C.C.; Klagsbrun, M. Tumor-associated endothelial cells with cytogenetic abnormalities. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 8249–8255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streubel, B.; Chott, A.; Huber, D.; Exner, M.; Jager, U.; Wagner, O.; Schwarzinger, I. Lymphoma-specific genetic aberrations in microvascular endothelial cells in B-cell lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.P.; Gires, O.; Wang, D.D.; Li, L.; Wang, H. Comprehensive in situ co-detection of aneuploid circulating endothelial and tumor cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akino, T.; Hida, K.; Hida, Y.; Tsuchiya, K.; Freedman, D.; Muraki, C.; Ohga, N.; Matsuda, K.; Akiyama, K.; Harabayashi, T.; et al. Cytogenetic abnormalities of tumor-associated endothelial cells in human malignant tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 2657–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.M.; Nevis, K.R.; Park, H.L.; Rogers, G.C.; Rogers, S.L.; Cook, J.G.; Bautch, V.L. Angiogenic factor signaling regulates centrosome duplication in endothelial cells of developing blood vessels. Blood 2010, 116, 3108–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitre, B.D.; Cleveland, D.W. Centrosomes, chromosome instability (CIN) and aneuploidy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2012, 24, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergsmedh, A.; Szeles, A.; Henriksson, M.; Bratt, A.; Folkman, M.J.; Spetz, A.-L.; Holmgren, L. Horizontal transfer of oncogenes by uptake of apoptotic bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnfors, J.; Kost-Alimova, M.; Persson, N.L.; Bergsmedh, A.; Castro, J.; Levchenko-Tegnebratt, T.; Yang, L.; Panaretakis, T.; Holmgren, L. Horizontal transfer of tumor DNA to endothelial cells in vivo. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsmedh, A.; Szeles, A.; Spetz, A.L.; Holmgren, L. Loss of the p21(Cip1/Waf1) cyclin kinase inhibitor results in propagation of horizontally transferred DNA. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 575–579. [Google Scholar]

- Domigan, C.K.; Warren, C.M.; Antanesian, V.; Happel, K.; Ziyad, S.; Lee, S.; Krall, A.; Duan, L.; Torres-Collado, A.X.; Castellani, L.W.; et al. Autocrine VEGF maintains endothelial survival through regulation of metabolism and autophagy. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, K.; Ohga, N.; Hida, Y.; Muraki, C.; Tsuchiya, K.; Kurosu, T.; Akino, T.; Shih, S.C.; Totsuka, Y.; Klagsbrun, M.; et al. Isolated tumor endothelial cells maintain specific character during long-term culture. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 394, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussolati, B.; Deambrosis, I.; Russo, S.; Deregibus, M.C.; Camussi, G. Altered angiogenesis and survival in human tumor-derived endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1159–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croix, B.S.; Rago, C.; Velculescu, V.; Traverso, G.; Romans, K.E.; Montgomery, E.; Lal, A.; Riggins, G.J.; Lengauer, C.; Vogelstein, B.; et al. Genes Expressed in Human Tumor Endothelium. Science 2000, 289, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, S.; Stevens, J.; Yang, M.Y.; Logsdon, D.; Graff-Cherry, C.; St Croix, B. Genes that distinguish physiological and pathological angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.K.; Bae, H.R.; Park, H.K.; Seo, I.A.; Lee, E.Y.; Suh, D.J.; Park, H.T. Cloning, characterization and neuronal expression profiles of tumor endothelial marker 7 in the rat brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2005, 136, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opavsky, R.; Haviernik, P.; Jurkovicova, D.; Garin, M.T.; Copeland, N.G.; Gilbert, D.J.; Jenkins, N.A.; Bies, J.; Garfield, S.; Pastorekova, S.; et al. Molecular characterization of the mouse Tem1/endosialin gene regulated by cell density in vitro and expressed in normal tissues in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 38795–38807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacFadyen, J.; Savage, K.; Wienke, D.; Isacke, C.M. Endosialin is expressed on stromal fibroblasts and CNS pericytes in mouse embryos and is downregulated during development. Gene Expr. Patterns 2007, 7, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, C.; Ossendorf, C.; Maran, A.; Yaszemski, M.; Bolander, M.E.; Fuchs, B.; Sarkar, G. Preferential expression of the secreted and membrane forms of tumor endothelial marker 7 transcripts in osteosarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 4317–4322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohga, N.; Ishikawa, S.; Maishi, N.; Akiyama, K.; Hida, Y.; Kawamoto, T.; Sadamoto, Y.; Osawa, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Kondoh, M.; et al. Heterogeneity of tumor endothelial cells: Comparison between tumor endothelial cells isolated from high- and low-metastatic tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 180, 1294–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maishi, N.; Annan, D.A.; Kikuchi, H.; Hida, Y.; Hida, K. Tumor Endothelial Heterogeneity in Cancer Progression. Cancers 2019, 11, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghilardi, C.; Chiorino, G.; Dossi, R.; Nagy, Z.; Giavazzi, R.; Bani, M. Identification of novel vascular markers through gene expression profiling of tumor-derived endothelium. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, S.L.; Cook, B.P.; Nacht, M.; Weber, W.D.; Callahan, M.R.; Jiang, Y.; Dufault, M.R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Walter-Yohrling, J.; et al. Vascular gene expression in nonneoplastic and malignant brain. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 165, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, W.C. Molecular heterogeneity of tumor endothelium. Cell Tissue Res. 2009, 335, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K.; Ohga, N.; Hida, Y.; Kawamoto, T.; Sadamoto, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Maishi, N.; Akino, T.; Kondoh, M.; Matsuda, A.; et al. Tumor endothelial cells acquire drug resistance by MDR1 up-regulation via VEGF signaling in tumor microenvironment. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 180, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.-Q.; Sun, H.-C.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.-D.; Zhuang, P.-Y.; Zhang, J.-B.; Wang, L.; Wu, W.-z.; Qin, L.-X.; Tang, Z.-Y. Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumor–derived Endothelial Cells Manifest Increased Angiogenesis Capability and Drug Resistance Compared with Normal Endothelial Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 4838–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begicevic, R.-R.; Falasca, M. ABC Transporters in Cancer Stem Cells: Beyond Chemoresistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohmura-Kakutani, H.; Akiyama, K.; Maishi, N.; Ohga, N.; Hida, Y.; Kawamoto, T.; Iida, J.; Shindoh, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Shinohara, N.; et al. Identification of Tumor Endothelial Cells with High Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Activity and a Highly Angiogenic Phenotype. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hida, K.; Kawamoto, T.; Maishi, N.; Morimoto, M.; Akiyama, K.; Ohga, N.; Shindoh, M.; Shinohara, N.; Hida, Y. miR-145 promoted anoikis resistance in tumor endothelial cells. J. Biochem. 2017, 162, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Kumar, B.; Yu, J.G.; Old, M.; Teknos, T.N.; Kumar, P. Tumor-Associated Endothelial Cells Promote Tumor Metastasis by Chaperoning Circulating Tumor Cells and Protecting Them from Anoikis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nör, J.E.; Christensen, J.; Liu, J.; Peters, M.; Mooney, D.J.; Strieter, R.M.; Polverini, P.J. Up-Regulation of Bcl-2 in Microvascular Endothelial Cells Enhances Intratumoral Angiogenesis and Accelerates Tumor Growth. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 2183. [Google Scholar]

- Maishi, N.; Ohba, Y.; Akiyama, K.; Ohga, N.; Hamada, J.; Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; Alam, M.T.; Yamamoto, K.; Kawamoto, T.; Inoue, N.; et al. Tumour endothelial cells in high metastatic tumours promote metastasis via epigenetic dysregulation of biglycan. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, X.; Carmeliet, P. Hallmarks of Endothelial Cell Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bock, K.; Georgiadou, M.; Schoors, S.; Kuchnio, A.; Wong, B.W.; Cantelmo, A.R.; Quaegebeur, A.; Ghesquière, B.; Cauwenberghs, S.; Eelen, G.; et al. Role of PFKFB3-Driven Glycolysis in Vessel Sprouting. Cell 2013, 154, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, D.A.; Maishi, N.; Soga, T.; Dawood, R.; Li, C.; Kikuchi, H.; Hojo, T.; Morimoto, M.; Kitamura, T.; Alam, M.T.; et al. Carbonic anhydrase 2 (CAII) supports tumor blood endothelial cell survival under lactic acidosis in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Commun. Signal 2019, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantelmo, A.R.; Conradi, L.C.; Brajic, A.; Goveia, J.; Kalucka, J.; Pircher, A.; Chaturvedi, P.; Hol, J.; Thienpont, B.; Teuwen, L.A.; et al. Inhibition of the Glycolytic Activator PFKFB3 in Endothelium Induces Tumor Vessel Normalization, Impairs Metastasis, and Improves Chemotherapy. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 968–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y. COX2 inhibition in the endothelium induces glucose metabolism normalization and impairs tumor progression. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 2937–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraki, C.; Ohga, N.; Hida, Y.; Nishihara, H.; Kato, Y.; Tsuchiya, K.; Matsuda, K.; Totsuka, Y.; Shindoh, M.; Hida, K. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition causes antiangiogenic effects on tumor endothelial and vascular progenitor cells. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruning, U.; Morales-Rodriguez, F.; Kalucka, J.; Goveia, J.; Taverna, F.; Queiroz, K.C.S.; Dubois, C.; Cantelmo, A.R.; Chen, R.; Loroch, S.; et al. Impairment of Angiogenesis by Fatty Acid Synthase Inhibition Involves mTOR Malonylation. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 866–880.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]