Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-positive mucocutaneous ulcer (EBVMCU) is a unifocal mucosal or cutaneous ulcer that often occurs after local trauma in patients with immunosuppression; the patients generally have a good prognosis. It is histologically characterized by proliferating EBV-positive atypical B cells accompanied by ulcers.

- EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer

- pathological features

- immunosuppression

1. Introduction

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is a member of the herpes virus family, and is one of the most common human viruses [1]. EBV causes latent infection in humans and it may lead to various diseases, including lymphomas and lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) even during the latency period. EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer (EBVMCU) is a recently established EBV-associated LPD, established in 2010. EBVMCUs are shallow, sharply circumscribed, mucosal, or cutaneous ulcers that are histologically characterized by the proliferation of EBV-positive, variable-sized, atypical B-lymphocytes. This lesion develops in immunocompromised patients, including those who are of advanced age or have iatrogenic immunosuppression, primary immune disorders, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated immune deficiencies. EBVMCU has a good prognosis, unlike other EBV-associated LPDs such as EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Almost all EBVMCU patients achieve remission with the reduction or discontinuation of immunosuppressants, or a watch-and-wait approach.

2. Pathological Findings for EBVMCU

EBVMCUs are characterized by localized mucosal or cutaneous ulcers with EBV-positive atypical lymphoid cells accompanied by dense polymorphic infiltration with various inflammatory cells such as plasma cells, histiocytes, and granulocytes. EBV-positive atypical cells range in size from small to large, and may resemble Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg (HRS)-like cells. Angioinvasion by these cells is often seen in EBVMCUs. In most cases, EBV-positive cells are positive for CD20 and CD79a and exhibit characteristics of B lymphocytes. These cells are usually also positive for CD30, PAX5, OCT2, and MUM1, with variable expression of BOB1. CD15 is expressed in approximately 50% of cases [1][2].

EBVMCUs are characterized by localized mucosal or cutaneous ulcers with EBV-positive atypical lymphoid cells accompanied by dense polymorphic infiltration with various inflammatory cells such as plasma cells, histiocytes, and granulocytes. EBV-positive atypical cells range in size from small to large, and may resemble Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg (HRS)-like cells. Angioinvasion by these cells is often seen in EBVMCUs. In most cases, EBV-positive cells are positive for CD20 and CD79a and exhibit characteristics of B lymphocytes. These cells are usually also positive for CD30, PAX5, OCT2, and MUM1, with variable expression of BOB1. CD15 is expressed in approximately 50% of cases [1,24].

In some cases of EBVMCUs, the pathological findings are similar to those of DLBCL or CHL. A recent study classified EBVMCUs into four morphological subtypes on the basis of histological features [3].

In some cases of EBVMCUs, the pathological findings are similar to those of DLBCL or CHL. A recent study classified EBVMCUs into four morphological subtypes on the basis of histological features [53].

2.1. Polymorphous

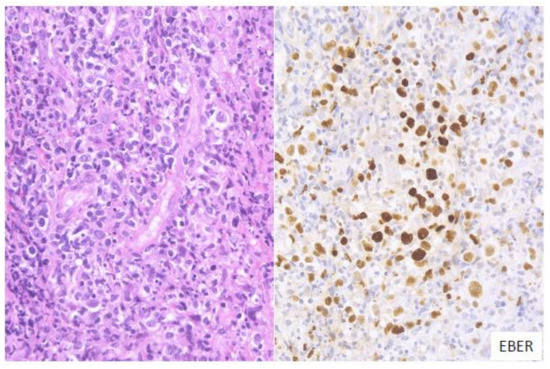

In this subtype of EBVMCU, various small-to-large atypical EBV-positive lymphoid cells, occasionally with a few HRS-like cells, are noted. Atypical lymphoid cells are found in dense clusters or are scattered (Figure 12). Fifty-nine percent of the cases in this study belonged to the polymorphous subtype [3][53].

Figure 12. Pathologic findings for polymorphous EBVMCU. A tonsillar EBVMCU in a patient undergoing methotrexate treatment. Atypical lymphoid cells with polymorphous morphology and angioinvasion are seen, and are positive for EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) (HE and EBER staining; magnification, ×400).

2.2. Large Cell-Rich

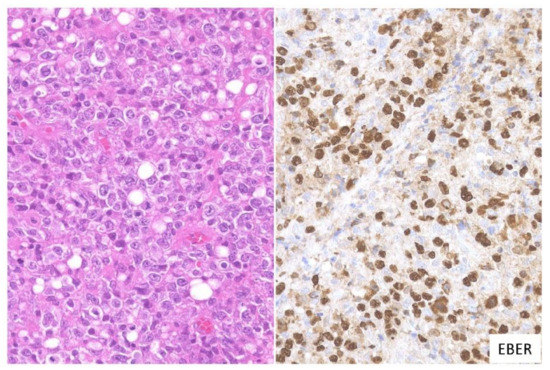

In this subtype, dense proliferation of large and monomorphic atypical EBV-positive lymphoid cells, similar to that in DLBCL, is noted (

Figure 2). Twenty-one percent of the cases in this study belonged to the large cell-rich subtype [3].

Figure 23.

2.3. CHL-Like

2.3. CHL-Like

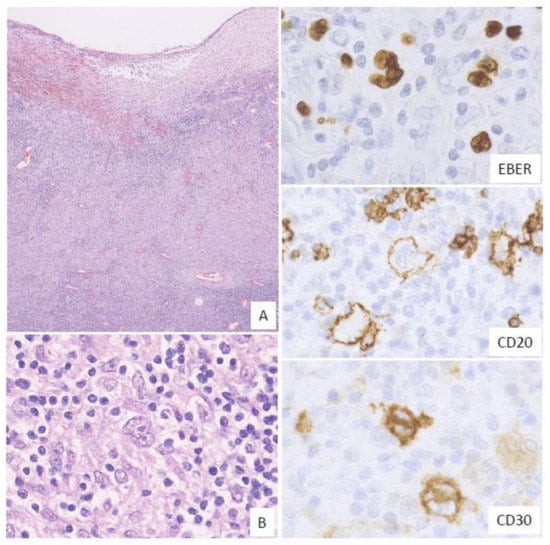

In this subtype, many HRS-like EBV-positive cells and various-sized EBV-positive atypical lymphoid cells, sometimes with epithelioid granulomas or eosinophil infiltration, are noted. The HRS-like cells are positive for CD30, similar to the findings for CHL (

Figure 3). Twelve percent of the EBVMCU cases were classified as CHL-like [3].

Figure 34.

A

B) This lesion contains many Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg (HRS)-like cells (magnification, ×400). The HRS-like cells and other polymorphous atypical lymphoid cells were positive for EBER; the HRS-like cells were also positive for CD20 and CD30 (EBER, CD20, and CD30: magnification, ×400).

2.4. Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) Lymphoma-Like

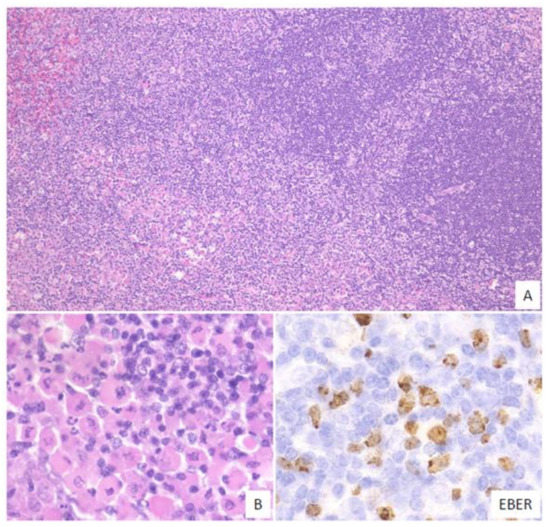

In this subtype, small-to-medium-sized atypical lymphoid cells that show centrocytic-like features and/or plasmacytic features and proliferate in the expanded interfollicular zone are noted (

Figure 4). In our previous study, 9% of the EBVMCU cases belonged to this subtype [3].

5). In our previous study, 9% of the EBVMCU cases belonged to this subtype [53].

Figure 45.

Pathologic findings for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma-like EBVMCU. A lingual EBVMCU in a patient undergoing methotrexate treatment. (

A

) The atypical lymphoid cells show centrocytic-like features with plasmacytic differentiation and are proliferating in the expanded interfollicular zone (magnification, ×100). (

B

) Atypical plasmacytic cells with Russell bodies are seen (magnification, ×400). The atypical lymphoid cells are positive for EBER (magnification, ×400).

3. Genetic Findings for EBVMCU

Genetic studies have been performed to characterize EBVMCUs, including the many reports on detection of clonality in EBVMCUs. In 2010, Dojcinov et al. was the first to report that 38% of the EBVMCUs studied exhibited immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) rearrangements [4]. Other studies reported that patients with EBVMCUs had a relatively lower frequency of clonal IGH rearrangements than patients with EBV-positive or EBV-negative DLBCLs [3][5]. In our previous study, clonal IGH rearrangements were detected in 44% of the EBVMCUs, 32% of EBV-positive DLBCLs, and 58% of EBV-negative DLBCLs; these differences were not statistically significant. Thus, IGH rearrangements are not useful for distinguishing between EBVMCU and DLBCL.

Genetic studies have been performed to characterize EBVMCUs, including the many reports on detection of clonality in EBVMCUs. In 2010, Dojcinov et al. was the first to report that 38% of the EBVMCUs studied exhibited immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) rearrangements [15]. Other studies reported that patients with EBVMCUs had a relatively lower frequency of clonal IGH rearrangements than patients with EBV-positive or EBV-negative DLBCLs [53,75]. In our previous study, clonal IGH rearrangements were detected in 44% of the EBVMCUs, 32% of EBV-positive DLBCLs, and 58% of EBV-negative DLBCLs; these differences were not statistically significant. Thus, IGH rearrangements are not useful for distinguishing between EBVMCU and DLBCL.

Clonal T cell receptor (TCR) rearrangements tend to occur more frequently in EBVMCUs than in EBV-positive and EBV-negative DLBCLs [3]. In our previous study, clonal TCR rearrangements were found in 32% of EBVMCUs, 10% of EBV-positive DLBCLs, and 15% of EBV-negative DLBCLs. Another previous study supported this T-cell clonality; in that study, serum CD8+ T cells increased after MTX reduction in patients who had MTX-LPD and achieved complete remission only due to MTX reduction [6]. Another study showed that B-cell post-transplant LPD was associated with clonal expansion of CD8+ T cells [7]. Thus, we considered that EBVMCU might also be associated with T-cell clonal expansion due to reduced immune surveillance.

Clonal T cell receptor (TCR) rearrangements tend to occur more frequently in EBVMCUs than in EBV-positive and EBV-negative DLBCLs [53]. In our previous study, clonal TCR rearrangements were found in 32% of EBVMCUs, 10% of EBV-positive DLBCLs, and 15% of EBV-negative DLBCLs. Another previous study supported this T-cell clonality; in that study, serum CD8+ T cells increased after MTX reduction in patients who had MTX-LPD and achieved complete remission only due to MTX reduction [76]. Another study showed that B-cell post-transplant LPD was associated with clonal expansion of CD8+ T cells [77]. Thus, we considered that EBVMCU might also be associated with T-cell clonal expansion due to reduced immune surveillance.

Some studies suggested that TCR gene rearrangements could lead to a limited T cell repertoire, which triggers EBV infections in the elderly and in immunocompromised patients [7][8]. The leading players in T cell-mediated immune responses are CD8+ mature memory T cells. In the patient population, T cell epitope recognition might be disabled due to dysfunction of CD8+ mature memory T cells and the CD8+ cells could miss the EBV epitope [8]. This T cell dysfunction might lead to an increase in the number of EBV-positive cells.

Some studies suggested that TCR gene rearrangements could lead to a limited T cell repertoire, which triggers EBV infections in the elderly and in immunocompromised patients [77,78]. The leading players in T cell-mediated immune responses are CD8+ mature memory T cells. In the patient population, T cell epitope recognition might be disabled due to dysfunction of CD8+ mature memory T cells and the CD8+ cells could miss the EBV epitope [78]. This T cell dysfunction might lead to an increase in the number of EBV-positive cells.

Recently, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) has received attention for its involvement in immune evasion systems. PD-L1 expression in cancer cells suppresses T cell activation, allowing cancer cells to escape the immune surveillance mechanism. Previous studies have shown the presence of PD-L1 expression in most cases of EBV-positive DLBCL [9][10][11]; however, PD-L1 expression was absent in almost all cases of EBVMCUs [12][13]. These results suggest that, in contrast to EBV-positive DLBCLs, EBVMCUs may not possess an immune evasion mechanism.

Recently, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) has received attention for its involvement in immune evasion systems. PD-L1 expression in cancer cells suppresses T cell activation, allowing cancer cells to escape the immune surveillance mechanism. Previous studies have shown the presence of PD-L1 expression in most cases of EBV-positive DLBCL [79,80,81]; however, PD-L1 expression was absent in almost all cases of EBVMCUs [64,82]. These results suggest that, in contrast to EBV-positive DLBCLs, EBVMCUs may not possess an immune evasion mechanism.