Blood flow modeling consists of using computational techniques to investigate the blood flow behavior in a rapid and accurate fashion. This has become an area of extensive research due to the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, responsible for a critical number of deaths every year worldwide, most of which are associated with atherosclerosis, a disease that causes unusual hemodynamic conditions in arteries. In the present review, the application of computational simulations by using different physiological conditions of blood flow, several rheological models, and boundary conditions, were discussed.

- atherosclerosis

- coronary arteries

- hemodynamics

- numerical methods

1. Introduction

Despite the progress done in experimental studies and blood flow measurement techniques, there are still some challenges associated with them [19][19]. For instance, in vitro wall shear stress (WSS) measurements are extremely difficult to perform and the velocity measurements have high associated errors. These, combined with other complications of directly measuring quantities of interest, have motivated the use of computer simulations to predict them in silico [69][69].

The earliest numerical detailed studies solving the flow problem in constricted tubes were conducted by Lee and Fung (1970) [70][70]. After that, other studies in this field conducted by Caro et al., (1971) [71][71], Glagov et al., (1989) [72][72], and Ku et al., (1985)[73] [73] are important references in this area and should be highlighted. Ever since, CFD approaches have been progressively adopted by most researchers as the preferred technique for numerical modeling of hemodynamics. Owing to the continued growth of computational power, these have become an increasingly reliable tool for measuring biomechanical factors vital for clinical decision-making and surgical planning. However, the proper selection of the flow boundary conditions has to be done, otherwise, the findings can be considered uncertain, weak, and unrealistic [74][74]. In this regard, the different geometries, boundary conditions, and flow characteristics applied by some researchers in the last ten years are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Numerical studies of hemodynamics and the respective assumptions for numerical simulations.

| Geometry | Schematic Representation | Modeling Approaches | Fluid | Boundary Conditions | Authors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wall | Inlet | Outlet | |||||

| Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Non-Newtonian (Carreau-Yasuda) | Rigid | Time-dependent velocity profile | Zero gauge pressure | Kashyap et al., (2020) [6] | |

| Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Newtonian | Rigid | Time-dependent mass flow profile | Zero surface tension | Biglarian et al., (2019) [75] | |

| Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Non-Newtonian (Cross model) | Rigid and Flexible | Constant inlet velocity | Constant pressure outlet (10 kPa) | Mulani et al., (2015) [57] | |

| Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Newtonian | Rigid and Flexible | Time-dependent flowrate profile | Time-dependent pressure profile | Wu et al., (2015) [58] | |

| Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Newtonian | Rigid | Constant inlet velocity (fully developed parabolic profile) | Constant pressure outlet (13 kPa) | Kenjereš et al., (2019) [76] | |

| Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Newtonian | Rigid | Constant inlet velocity | Zero gauge pressure | Carvalho et al., (2020) [47] | |

| Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| k-ω turbulent model | Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | Rigid | Spiral boundary conditionwith a parabolic velocity profile | Zero gauge pressure | Kabir et al., (2018) [77] | |

| Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| k-ω turbulent model (SST) | Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | Rigid | Time-dependent velocity profile | Zero gauge pressure | Carvalho et al., (2020) [42] | |

| Idealized | ||||||

|

k-ω turbulent model (SST) | Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | Rigid | |||

| Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | ||||||

| Time-dependent velocity profile | Zero gauge pressure | |||||

| Rigid | ||||||

| Carvalho et al., (2020) [ | ||||||

| Time-dependent velocity profile | ||||||

| 59 | ||||||

| Zero gauge pressure | ||||||

| , | 78 | ] | ||||

| k-ω turbulent model (SST) | Carvalho et al., (2020) | [ | 59 | ][78] | ||

| Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| N.A | ||||||

| 1 | ||||||

| Newtonian | Flexible | Time-dependent velocity profile | Time-dependent pressure profile | Jahromi et al., (2019) [79] | ||

| Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Newtonian | Rigid | Time-dependent velocity profile | Flow partition implied in Murray’s law | Doutel et al., (2018) [11] | |

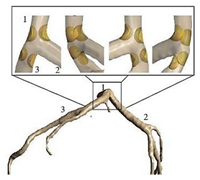

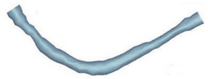

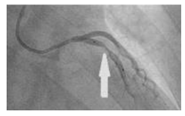

| Patient-specific | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Non-Newtonian (Generalized power-law model) and Newtonian | Rigid | Time-dependent flow rate profile | Time-dependent pressure profile | Chaichana et al., (2012) [60] | |

| Patient-specific | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | Rigid | Time-dependent velocity profile | Time-dependent pressure profile | Liu et al., (2015) [80] | |

| Patient-specific | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Newtonian | Rigid and Flexible | Time-dependent pressure profile | Parabolic velocity profile | Siogkas et al., (2014) [81] | |

| Patient-specific | ||||||

| ||||||

| N.A | Newtonian | Rigid | Time-dependent pressure profile | Constant pressure outlet (9.85 kPa) | Zhao et al., (2019) [82] | |

| Patient-specific | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | Rigid | Time-dependent velocity profile | Flow partition implied in Murray’s law | Pandey et al., (2020) [43] | |

| Patient-specific | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | Rigid | Various time-dependent velocity profiles | Flow partition implied in Murray’s law | Rizzini et al., (2020) [74] | |

| Patient-specific | ||||||

| ||||||

| N.A | Non-Newtonian (Power-law model) | Rigid | Time-dependent velocity profile | Pressure outlet (N.A) | Zhang et al., (2020) [83] | |

| Patient-specific | ||||||

| ||||||

| k-ω turbulent model (SST) | Non-Newtonian (Bird-Carreau model) | Rigid | Time-dependent velocity profile | Constant pressure outlet (10 kPa) | Kamangar et al., (2019) [64] | |

| Patient-specific | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Newtonian | Rigid | Time-dependent flow rate profile | Two-Element Windkessel Model | Lo et al., (2019) [84] | |

| Patient-specific and Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Newtonian and Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | Rigid | Constant inlet velocity and Time-dependent velocity profile | N.A | Doutel et al., (2019) [85] | |

| Patient-specific and Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| k-ω turbulent model (SST) | Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | Rigid | Time-dependent velocity profile | Outflow condition | Mahalingam et al., (2016) [86] | |

| Patient-specific and Idealized | ||||||

|

N.A | Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | Rigid | Time-dependent velocity profile | Constant pressure outlet (10 kPa) | Rabbi et al., (2020) [87] |

| N.A | Non-Newtonian (Carreau model) | Rigid | Time-dependent velocity profile | Constant pressure outlet (10 kPa) | Rabbi et al., (2020)[87] | |

| Patient-specific and Idealized | ||||||

| ||||||

| Laminar | Newtonian | Rigid | Constant inlet mass flow and Time-dependent flow rate | Zero gauge pressure | Malota et al., (2018) [88] |

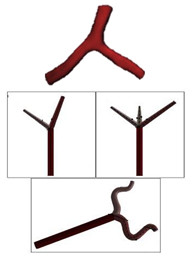

In general, from the above-mentioned investigations, it can be seen that, regardless of the type of geometry, the majority of authors consider that the blood is a non-Newtonian fluid, usually approximated by the Carreau model, with a laminar behavior. Regarding the boundary conditions, in most cases, the wall is considered rigid, and at the inlet, a pulsatile velocity is applied. At the outlet, the condition set mainly depends on the study, but either the default conditions are maintained, or pressures are applied, time-dependent or constant values. In the following section, the main observations drawn from these studies are presented.

2. Concluding rRemarks and fFuture pPerspectives

Although huge advancements have been made in imaging techniques to obtain patient-specific images, this step is time-consuming, and it is still a challenging task for all researchers. For this reason, nowadays, idealized models continue to be widely used by researchers, since these allow to obtain important and relevant results, without requiring much computational time and without the need to collect the medical images, which is highly time-consuming. In this regard, a promising study was proposed by Doutel et al., (2018) [1] wherein artificial, but realistic stenosis can be generated.

Although huge advancements have been made in imaging techniques to obtain patient-specific images, this step is time-consuming, and it is still a challenging task for all researchers. For this reason, nowadays, idealized models continue to be widely used by researchers, since these allow to obtain important and relevant results, without requiring much computational time and without the need to collect the medical images, which is highly time-consuming. In this regard, a promising study was proposed by Doutel et al., (2018) wherein artificial, but realistic stenosis can be generated.

It was also noted that, although the modelling of blood as a Newtonian fluid is a good approximation for large vessels with high shear rates, the assumption of non-Newtonian behavior of blood flow has been increasingly used in the presence of stenosis. From the overall studies, the most used models are the Carreau and the Carreau-Yasuda, and these have also been indicated as the most appropriate to simulate the blood rheology by Razavi et al., (2011) [2]. Nevertheless, currently, one cannot say which is the right model, because there is not yet enough evidence in the literature to prove which model fully expresses the complex nature of blood rheology and its dependence on many biological factors [3]. Accordingly, it is of great importance to obtain proper models for CFD analysis that take into account the non-Newtonian behavior of blood. For this purpose, more experimental studies are needed. Regarding the boundary conditions, few studies have evaluated the impact of using different inlet and outlet boundary conditions [4][5], and therefore, it would be interesting, in future studies, to investigate what are the profiles more adequate to study the blood flow behavior in coronary arteries.

It was also noted that, although the modelling of blood as a Newtonian fluid is a good approximation for large vessels with high shear rates, the assumption of non-Newtonian behavior of blood flow has been increasingly used in the presence of stenosis. From the overall studies, the most used models are the Carreau and the Carreau-Yasuda, and these have also been indicated as the most appropriate to simulate the blood rheology by Razavi et al., (2011) . Nevertheless, currently, one cannot say which is the right model, because there is not yet enough evidence in the literature to prove which model fully expresses the complex nature of blood rheology and its dependence on many biological factors . Accordingly, it is of great importance to obtain proper models for CFD analysis that take into account the non-Newtonian behavior of blood. For this purpose, more experimental studies are needed. Regarding the boundary conditions, few studies have evaluated the impact of using different inlet and outlet boundary conditions , and therefore, it would be interesting, in future studies, to investigate what are the profiles more adequate to study the blood flow behavior in coronary arteries.

Despite the great efforts that have been made so far, the blood has been mainly modeled as a single-phase fluid. However, blood is a mixture of plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. Therefore, the consideration of multiphase models is of great importance when modeling atherosclerotic lesions. Although some studies have already applied these models [6][7][8][9], the research is still in the beginning. Moreover, it should be also noted that the use of these models is a promising option for studying nanoparticle-mediated targeted drug delivery treatment of atherosclerosis. In this context, a promising study was conducted by Zhang et al., (2020)[7]. The authors used an Eulerian-Lagrangian approach coupled with FSI to investigate the impact of plaque morphology on magnetic nanoparticles targeting under the action of an external field.

Despite the great efforts that have been made so far, the blood has been mainly modeled as a single-phase fluid. However, blood is a mixture of plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. Therefore, the consideration of multiphase models is of great importance when modeling atherosclerotic lesions. Although some studies have already applied these models , the research is still in the beginning. Moreover, it should be also noted that the use of these models is a promising option for studying nanoparticle-mediated targeted drug delivery treatment of atherosclerosis. In this context, a promising study was conducted by Zhang et al., (2020). The authors used an Eulerian-Lagrangian approach coupled with FSI to investigate the impact of plaque morphology on magnetic nanoparticles targeting under the action of an external field.

Due to the continuous improvements acquired in computational methods, in the following years more amazing and complex hemodynamic studies will be performed. The work of Zhao et al. (2019) [10] should be highlighted since their numerical approach has a great potential to achieve more realistic simulations. They have simulated 4D hemodynamic profiles of time-resolved blood flow. The results proved that these simulations can provide extensive information about blood flow, both qualitatively and quantitatively that may be advantageous for future investigations of clinical diagnosis and treatment of atherosclerosis.

Due to the continuous improvements acquired in computational methods, in the following years more amazing and complex hemodynamic studies will be performed. The work of Zhao et al. (2019) should be highlighted since their numerical approach has a great potential to achieve more realistic simulations. They have simulated 4D hemodynamic profiles of time-resolved blood flow. The results proved that these simulations can provide extensive information about blood flow, both qualitatively and quantitatively that may be advantageous for future investigations of clinical diagnosis and treatment of atherosclerosis.

To conclude, although computational methods have been extensively used for atherosclerosis investigations in recent years, they are expected to become more popular and more effective to simulate the blood flow in the cardiovascular system, and consequently, they will promote medical innovation at an affordable cost. However, to this end, active collaborations between engineers and medical staff are needed to assure the successful application of this technique in atherosclerosis treatment.

Reference (Editors will rearrange the references after the entry is submitted)

To conclude, although computational methods have been extensively used for atherosclerosis investigations in recent years, they are expected to become more popular and more effective to simulate the blood flow in the cardiovascular system, and consequently, they will promote medical innovation at an affordable cost. However, to this end, active collaborations between engineers and medical staff are needed to assure the successful application of this technique in atherosclerosis treatment.

References

- E. Doutel; J. Carneiro; J.B.L.M. Campos; J.M. Miranda; Artificial stenoses for computational hemodynamics. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2018, 59, 427-440, 10.1016/j.apm.2018.01.029.World Health Organization (WHO). Cardiovasc. Dis. Fact Sheet No.317, 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/fact_sheet_cardiovascular_en.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- A. Razavi; Ebrahim Shirani; M.R. Sadeghi; Numerical simulation of blood pulsatile flow in a stenosed carotid artery using different rheological models. Journal of Biomechanics 2011, 44, 2021-2030, 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.04.023.Haverich, A.; Boyle, E.C. Atherosclerosis Pathogenesis and Microvascular Dysfunction, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 9783030202446.

- Jack Lee; Nicolas P. Smith; The Multi-Scale Modelling of Coronary Blood Flow. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 2012, 40, 2399-2413, 10.1007/s10439-012-0583-7.Libby, P.; Buring, J.E.; Badimon, L.; Hansson, G.K.; Deanfield, J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Tokgözoğlu, L.; Lewis, E.F. Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2019, 5, 1–18.

- Maurizio Lodi Rizzini; Diego Gallo; Giuseppe De Nisco; Fabrizio D'ascenzo; Claudio Chiastra; Pier Paolo Bocchino; Francesco Piroli; Gaetano Maria De Ferrari; Umberto Morbiducci; Does the inflow velocity profile influence physiologically relevant flow patterns in computational hemodynamic models of left anterior descending coronary artery?. Medical Engineering & Physics 2020, 82, 58-69, 10.1016/j.medengphy.2020.07.001.Badimon, L.; Vilahur, G. Thrombosis formation on atherosclerotic lesions and plaque rupture. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 276, 618–632.

- Alina G Van Der Giessen; Harald C. Groen; Pierre-André Doriot; Pim J. De Feyter; A.F.W. Van Der Steen; Frans N. Van De Vosse; J.J. Wentzel; F. J. H. Gijsen; The influence of boundary conditions on wall shear stress distribution in patients specific coronary trees. Journal of Biomechanics 2011, 44, 1089-1095, 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.01.036.Lusis, A.J. Atherosclerosis. Nature 2000, 407, 233–241.

- Violeta Carvalho; Nelson Rodrigues; Ricardo Ribeiro; Pedro F. Costa; José C. F. Teixeira; Rui A. Lima; Senhorinha F. C. F. Teixeira; Hemodynamic study in 3D printed stenotic coronary artery models: experimental validation and transient simulation. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering 2020, 2, 1-14, 10.1080/10255842.2020.1842377.Kashyap, V.; Arora, B.B.; Bhattacharjee, S. A computational study of branch-wise curvature in idealized coronary artery bifurcations. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2020, 4, 100027.

- Xuelan Zhang; Mingyao Luo; Erhui Wang; Liancun Zheng; Chang Shu; Numerical simulation of magnetic nano drug targeting to atherosclerosis: Effect of plaque morphology (stenosis degree and shoulder length). Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2020, 195, 105556, 10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105556.Sun, Y.; Guan, X. Autophagy: A new target for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Front. Lab. Med. 2018, 2, 68–71.

- Wei-Tao Wu; Yubai Li; Nadine Aubry; Mehrdad Massoudi; James F. Antaki; Numerical Simulation of Red Blood Cell-Induced Platelet Transport in Saccular Aneurysms. Applied Sciences 2017, 7, 484, 10.3390/app7050484.Carpenter, H.J.; Gholipour, A.; Ghayesh, M.H.; Zander, A.C.; Psaltis, P.J. A review on the biomechanics of coronary arteries. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 147, 103201.

- Abdulrajak Buradi; Sumant Morab; Arun Mahalingam; EFFECT OF STENOSIS SEVERITY ON SHEAR-INDUCED DIFFUSION OF RED BLOOD CELLS IN CORONARY ARTERIES. Journal of Mechanics in Medicine and Biology 2019, 19, 1950034, 10.1142/s0219519419500349.Lopes, D.; Puga, H.; Teixeira, J.; Lima, R. Blood flow simulations in patient-specific geometries of the carotid artery: A systematic review. J. Biomech. 2020, 111, 110019.

- Yinghong Zhao; Jie Ping; Xianchao Yu; Renyuan Wu; Cunjie Sun; Min Zhang; Fractional flow reserve-based 4D hemodynamic simulation of time-resolved blood flow in left anterior descending coronary artery. Clinical Biomechanics 2019, 70, 164-169, 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2019.09.003.Zaromytidou, M.; Siasos, G.; Coskun, A.U.; Lucier, M.; Antoniadis, A.P.; Papafaklis, M.I.; Koskinas, K.C.; Andreou, I.; Feldman, C.L.; Stone, P.H. Intravascular hemodynamics and coronary artery disease: New insights and clinical implications. Hell. J. Cardiol. 2016, 57, 389–400.

- Doutel, E.; Carneiro, J.; Campos, J.B.L.M.; Miranda, J.M. Experimental and numerical methodology to analyze flows in a coronary bifurcation. Eur. J. Mech. B Fluids 2018, 67, 341–356.

- Nisco, G.D.; Hoogendoorn, A.; Chiastra, C.; Gallo, D.; Kok, A.M.; Morbiducci, U.; Wentzel, J.J. The impact of helical flow on coronary atherosclerotic plaque development. Atherosclerosis 2020, 1–8.

- Samady, H.; Eshtehardi, P.; McDaniel, M.C.; Suo, J.; Dhawan, S.S.; Maynard, C.; Timmins, L.H.; Quyyumi, A.A.; Giddens, D.P. Coronary artery wall shear stress is associated with progression and transformation of atherosclerotic plaque and arterial remodeling in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 2011, 124, 779–788.

- Han, D.; Starikov, A.; Hartaigh, B.; Gransar, H.; Kolli, K.K.; Lee, J.H.; Rizvi, A.; Baskaran, L.; Schulman-Marcus, J.; Lin, F.Y.; et al. Relationship between endothelial wall shear stress and high-risk atherosclerotic plaque characteristics for identification of coronary lesions that cause ischemia: A direct comparison with fractional flow reserve. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, 1–10.

- Siasos, G.; Sara, J.D.; Zaromytidou, M.; Park, K.H.; Coskun, A.U.; Lerman, L.O.; Oikonomou, E.; Maynard, C.C.; Fotiadis, D.; Stefanou, K.; et al. Local Low Shear Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction in Patients With Nonobstructive Coronary Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2092–2102.

- Soulis, J.V.; Fytanidis, D.K.; Seralidou, K.V.; Giannoglou, G.D. Wall shear stress oscillation and its gradient in the normal left coronary artery tree bifurcations. Hippokratia 2014, 18, 12–16.

- Zuo, Y.; Estes, S.K.; Ali, R.A.; Gandhi, A.A.; Yalavarthi, S.; Shi, H.; Sule, G.; Gockman, K.; Madison, J.A.; Zuo, M.; et al. Prothrombotic autoantibodies in serum from patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 3876, 1–17.

- Pandey, R.; Kumar, M.; Majdoubi, J.; Rahimi-Gorji, M.; Srivastav, V.K. A review study on blood in human coronary artery: Numerical approach. Comput. Methods Program. Biomed. 2020, 187, 105243.

- Carvalho, V.; Maia, I.; Souza, A.; Ribeiro, J.; Costa, P.; Puga, H.; Teixeira, S.F.C.F.; Lima, R.A. In vitro stenotic arteries to perform blood analogues flow visualizations and measurements: A Review. Open Biomed. Eng. J. 2020, 14, 87–102.

- LaDisa, J.F.; Olson, L.E.; Douglas, H.A.; Warltier, D.C.; Kersten, J.R.; Pagel, P.S. Alterations in regional vascular geometry produced by theoretical stent implantation influence distributions of wall shear stress: Analysis of a curved coronary artery using 3D computational fluid dynamics modeling. Biomed. Eng. Online 2006, 5, 1–11.

- Griggs, R.; Wing, E.F.G. Cecil Essentials of Medicine, 9th ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781437718997.

- Kabinejadian, F.; Ghista, D.N.; Su, B.; Kaabi Nezhadian, M.; Chua, L.P.; Yeo, J.H.; Leo, H.L. In vitro measurements of velocity and wall shear stress in a novel sequential anastomotic graft design model under pulsatile flow conditions. Med. Eng. Phys. 2014, 36, 1233–1245.

- Hewlin, R.L.; Kizito, J.P. Development of an Experimental and Digital Cardiovascular Arterial Model for Transient Hemodynamic and Postural Change Studies: “A Preliminary Framework Analysis”. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9.

- Park, S.M.; Min, Y.U.; Kang, M.J.; Kim, K.C.; Ji, H.S. In vitro hemodynamic study on the stenotic right coronary artery using experimental and numerical analysis. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2010, 10, 695–712.

- Souza, A.; Souza, M.S.; Pinho, D.; Agujetas, R.; Ferrera, C.; Lima, R.; Puga, H.; Ribeiro, J. 3D Manufacturing of Intracranial aneurysm biomodels for flow visualizations: A low-cost fabrication process. Mech. Res. Commun. 2020, 107, 103535.

- Bento, D.; Lopes, S.; Maia, I.; Lima, R.; Miranda, J.M. Bubbles moving in blood flow in a microchannel network: The effect on the local hematocrit. Micromachines 2020, 11, 344.

- Pinho, D.; Carvalho, V.; Gonçalves, I.M.; Teixeira, S.; Lima, R. Visualization and measurements of blood cells flowing in microfluidic systems and blood rheology: A personalized medicine perspective. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 249.

- Carvalho, V.; Sousa, P.; Pinto, V.; Ribeiro, R.; Costa, P.; Teixeira, S.F.C.F.; Lima, R.A. Hemodynamic studies in coronary artery models manufactured by 3D printing. In Proceedings of the International Conference Innovation in Engineering, Guimarães, Portugal, 28–30 June 2021. accepted.

- Stepniak, K.; Ursani, A.; Paul, N.; Naguib, H. Development of a phantom network for optimization of coronary artery disease imaging using computed tomography. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2019, 5, 45019.

- Sjostrand, S.; Widerstrom, A.; Ahlgren, A.R.; Cinthio, M. Design and fabrication of a conceptual arterial ultrasound phantom capable of exhibiting longitudinal wall movement. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2017, 64, 11–18.

- Papathanasopoulou, P.; Zhao, S.; Köhler, U.; Robertson, M.B.; Long, Q.; Hoskins, P.; Xu, X.Y.; Marshall, I. MRI measurement of time-resolved wall shear stress vectors in a carotid bifurcation model, and comparison with CFD predictions. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2003, 17, 153–162.

- Chayer, B.; Hoven, M.; Cardinal, M.-H.; Hongliang, L.; Lopata, R.; Cloutier, G. Atherosclerotic carotid bifurcation phantoms with stenotic soft inclusion for ultrasound flow and vessel wall elastography imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2019, 64, 95025.

- Goudot, G.; Poree, J.; Pedreira, O.; Khider, L.; Julia, P.; Alsac, J.; Laborie, E.; Mirault, T.; Tanter, M.; Messas, E.; et al. Wall Shear Stress Measurement by Ultrafast Vector Flow Imaging for Atherosclerotic Carotid Stenosis. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40.

- Karimi, A.; Navidbakhsh, M.; Shojaei, A.; Faghihi, S. Measurement of the uniaxial mechanical properties of healthy and atherosclerotic human coronary arteries. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 2550–2554.

- Karimi, A.; Navidbakhsh, M.; Shojaei, A.; Hassani, K.; Faghihi, S. Study of plaque vulnerability in coronary artery using Mooney-Rivlin model: A combination of finite element and experimental method. Biomed. Eng. Appl. Basis Commun. 2014, 26, 1–7.

- Santamore, W.; Walinsky, P.; Bove, A.; Cox, R.; Carey, R.A.; Spann, J.F. The effects of vasoconstriction on experimental coronary artery stenosis. Am. Heart J. 1980, 100, 852–858.

- Friedman, M.H.; Giddens, D.P. Blood flow in major blood vessels—Modeling and experiments. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2005, 33, 1710–1713.

- Rezvan, A.; Ni, C.W.; Alberts-Grill, N.; Jo, H. Animal, in vitro, and ex vivo models of flow-dependent atherosclerosis: Role of oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1433–1448.

- Yazdi, S.G.; Geoghegan, P.H.; Docherty, P.D.; Jermy, M.; Khanafer, A. A Review of Arterial Phantom Fabrication Methods for Flow Measurement Using PIV Techniques. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 46, 1697–1721.

- Fröhlich, E.; Salar-behzadi, S. Toxicological Assessment of Inhaled Nanoparticles: Role of in Vivo, ex Vivo, in Vitro, and in Silico Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 4795–4822.

- Rodrigues, R.; Sousa, P.; Gaspar, J.; Bañobre-López, M.; Lima, R.; Minas, G. Organ-on-a-chip: A Preclinical Microfluidic Platform for the Progress of Nanomedicine. Small 2020, 1–19.

- Carvalho, V.; Rodrigues, N.; Ribeiro, R.; Costa, P.; Teixeira, J.C.F.; Lima, R.; Teixeira, S.F.C.F. Hemodynamic study in 3D printed stenotic coronary artery models: Experimental validation and transient simulation. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 1–14.

- Pandey, R.; Kumar, M.; Srivastav, V.K. Numerical computation of blood hemodynamic through constricted human left coronary artery: Pulsatile simulations. Comput. Methods Program. Biomed. 2020, 197, 105661.

- Lopes, D.; Puga, H.; Teixeira, J.C.; Teixeira, S.F. Influence of arterial mechanical properties on carotid blood flow: Comparison of CFD and FSI studies. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 160, 209–218.

- Elhanafy, A.; Elsaid, A.; Guaily, A. Numerical investigation of hematocrit variation effect on blood flow in an arterial segment with variable stenosis degree. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 313, 113550.

- Carvalho, V.; Carneiro, F.; Ferreira, A.C.; Gama, V.; Teixeira, J.C.F.; Teixeira, S.F.C.F. Numerical study of the unsteady flow in simplified and realistic iliac bifurcation models. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2021. under review.

- Carvalho, V.; Rodrigues, N.; Ribeiro, R.; Costa, P.F.; Lima, R.A.; Teixeira, S.F.C.F. 3D Printed Biomodels for Flow Visualization in Stenotic Vessels: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Micromachines 2020, 11, 549.

- Versteeg, H.K.; Malalasekera, W. An Introduction to Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Finite Volume Method, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780131274983.

- Hoving, A.M.; de Vries, E.E.; Mikhal, J.; de Borst, G.J.; Slump, C.H. A Systematic Review for the Design of In Vitro Flow Studies of the Carotid Artery Bifurcation. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2019, 11, 111–127.

- Yilmaz, F.; Gundogdu, M.Y. A critical review on blood flow in large arteries; relevance to blood rheology, viscosity models, and physiologic conditions. Korea Aust. Rheol. J. 2008, 20, 197–211.

- Lee, J.; Smith, N.P. The multi-scale modelling of coronary blood flow. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 40, 2399–2413.

- Lieber, B.B.; Siebes, M.; Yamaguchi, T. Correlation of hemodynamic events with clinical and pathological observations. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2005, 33, 1695–1703.

- Zhang, J.-M.; Zhong, L.; Su, B.; Wan, M.; ShyaYap, J.; Tham, J.P.L.; Poh Chua, L.; Ghista, D.N.; San Tan, R. Perspective on CFD studies of coronary artery disease lesions and hemodynamics: A review Jun-Mei. Int. J. Numer. Method. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 30, 659–680.

- Sriyab, S. Mathematical Analysis of Non-Newtonian Blood Flow in Stenosis Narrow Arteries. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2014, 2014, 479152.

- Chen, C.X.; Ding, Y.; Gear, J.A. Numerical simulation of atherosclerotic plaque growth using two-way fluid-structural interaction. ANZIAM J. 2012, 53, 277.

- Razavi, A.; Shirani, E.; Sadeghi, M.R. Numerical simulation of blood pulsatile flow in a stenosed carotid artery using different rheological models. J. Biomech. 2011, 44, 2021–2030.

- Mulani, S.S.; Jagad, P.I. Analysis of the Effects of Plaque Deposits on the Blood Flow through Human Artery. Int. Eng. Res. J. 2015, 41, 2319–3182.

- Wu, J.; Liu, G.; Huang, W.; Ghista, D.N.; Wong, K.K.L. Transient blood flow in elastic coronary arteries with varying degrees of stenosis and dilatations: CFD modelling and parametric study. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 18, 1835–1845.

- Carvalho, V.; Rodrigues, N.; Lima, R.A.; Teixeira, S.F.C.F. Modeling blood pulsatile turbulent flow in stenotic coronary arteries. Int. J. Biol. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 14, 1998–4510.

- Chaichana, T.; Sun, Z.; Jewkes, J. Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis of the Effect of Plaques in the Left Coronary Artery. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2012, 2012, 504367.

- Shanmugavelayudam, S.K.; Rubenstein, D.A.; Yin, W. Effect of geometrical assumptions on numerical modeling of coronary blood flow under normal and disease conditions. J. Biomech. Eng. 2010, 132, 1–8.

- Chaichana, T.; Sun, Z.; Jewkes, J. Hemodynamic impacts of various types of stenosis inthe left coronary artery bifurcation: A patient-specific analysis. Phys. Med. 2013, 29, 447–452.

- Dabagh, M.; Takabe, W.; Jalali, P.; White, S.; Jo, H. Hemodynamic features in stenosed coronary arteries: CFD analysis based on histological images. J. Appl. Math. 2013, 2013, 11.

- Kamangar, S.; Salman Ahmed, N.J.; Badruddin, I.A.; Al-Rawahi, N.; Husain, A.; Govindaraju, K.; Yunus Khan, T.M. Effect of stenosis on hemodynamics in left coronary artery based on patient-specific CT scan. Biomed. Mater. Eng. 2019, 30, 463–473.

- Kim, H.J.; Vignon-Clementel, I.E.; Coogan, J.S.; Figueroa, C.A.; Jansen, K.E.; Taylor, C.A. Patient-specific modeling of blood flow and pressure in human coronary arteries. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 38, 3195–3209.

- Rubenstein, D.A.; Yin, W.; Frame, M. Biofluid Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 9780128009444.

- Formaggia, L.; Perktold, K.; Quarteroni, A. Cardiovascular Mathematics- Modeling and Simulation of the Circulatory System, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 53, ISBN 9788578110796.

- Ku, D. Blood flow in arteries. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1997, 29, 399–434.

- Kissas, G.; Yang, Y.; Hwuang, E.; Witschey, W.R.; Detre, J.A.; Perdikaris, P. Machine learning in cardiovascular flows modeling: Predicting arterial blood pressure from non-invasive 4D flow MRI data using physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2020, 358, 112623.

- Lee, J.; Fung, Y. Flow in Locally Constricted Tubes at Low Reynolds Numbers. J. Appl. Mech. 1970, 37, 9–16.

- Caro, C.G.; Fitz-Gerald, J.M.; Schroter, R.C. Atheroma and arterial wall shear. Observation, correlation and proposal of a shear dependent mass transfer mechanism for atherogenesis. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1971, 177, 109–159.

- Glagov, S.; Zarins, C.K.; Giddens, D.P.; Ku, D.N. Mechanical Factors in the Pathogenesis, Localization and Evolution of Atherosclerotic Plaques. In Diseases of the Arterial Wall; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; pp. 217–239.

- Ku, D.N.; Giddens, D.P.; Zarins, C.K.; Glagov, S. Pulsatile flow and atherosclerosis in the human carotid bifurcation. Positive correlation between plaque location and low and oscillating shear stress. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1985, 5, 293–302.

- Lodi Rizzini, M.; Gallo, D.; De Nisco, G.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Chiastra, C.; Bocchino, P.P.; Piroli, F.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Morbiducci, U. Does the inflow velocity profile influence physiologically relevant flow patterns in computational hemodynamic models of left anterior descending coronary artery? Med. Eng. Phys. 2020, 82, 58–69.

- Biglarian, M.; Larimi, M.M.; Afrouzi, H.H.; Moshfegh, A.; Toghraie, D.; Javadzadegan, A.; Rostami, S.; Momeni, M.; Hassanzadeh, H.; Moshfegh, A.; et al. Computational investigation of stenosis in curvature of coronary artery within both dynamic and static models. Comput. Methods Program. Biomed. 2020, 185, 105170.

- Kenjereš, S.; van der Krieke, J.P.; Li, C. Endothelium resolving simulations of wall shear-stress dependent mass transfer of LDL in diseased coronary arteries. Comput. Biol. Med. 2019, 114.

- Kabir, M.A.; Alam, M.F.; Uddin, M.A. A numerical study on the effects of reynolds number on blood flow with spiral velocity through regular arterial stenosis. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2018, 45, 2515–2527.

- Carvalho, V.; Rodrigues, N.; Lima, R.A.; Teixeira, S. Numerical simulation of blood pulsatile flow in stenotic coronary arteries: The effect of turbulence modeling and non-Newtonian assumptions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Mathematics & Computer Science, Athens, Greece, 2–4 June 2020.

- Jahromi, R.; Pakravan, H.A.; Saidi, M.S.; Firoozabadi, B. Primary stenosis progression versus secondary stenosis formation in the left coronary bifurcation: A mechanical point of view. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 39, 188–198.

- Liu, B.; Zheng, J.; Bach, R.; Tang, D. Influence of model boundary conditions on blood flow patterns in a patient specific stenotic right coronary artery. Biomed. Eng. Online 2015, 14, S6.

- Siogkas, P.K.; Papafaklis, M.I.; Sakellarios, A.I.; Stefanou, K.A.; Bourantas, C.V.; Athanasiou, L.S.; Exarchos, T.P.; Naka, K.K.; Michalis, L.K.; Parodi, O.; et al. Patient-specific simulation of coronary artery pressure measurements: An in vivo three-dimensional validation study in humans. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2015, 628416.

- Zhao, Y.; Ping, J.; Yu, X.; Wu, R.; Sun, C.; Zhang, M. Fractional flow reserve-based 4D hemodynamic simulation of time-resolved blood flow in left anterior descending coronary artery. Clin. Biomech. 2019, 70, 164–169.

- Zhang, X.; Luo, M.; Wang, E.; Zheng, L.; Shu, C. Numerical simulation of magnetic nano drug targeting to atherosclerosis: Effect of plaque morphology (stenosis degree and shoulder length). Comput. Methods Program. Biomed. 2020, 195, 105556.

- Lo, E.W.C.; Menezes, L.J.; Torii, R. Impact of inflow boundary conditions on the calculation of CT-based FFR. Fluids 2019, 4, 60.

- Doutel, E.; Viriato, N.; Carneiro, J.; Campos, J.B.L.M.; Miranda, J.M. Geometrical effects in the hemodynamics of stenotic and non-stenotic left coronary arteries—Numerical and in vitro approaches. Int. J. Numer. Method. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 35, 1–18.

- Mahalingam, A.; Gawandalkar, U.U.; Kini, G.; Buradi, A.; Araki, T.; Ikeda, N.; Nicolaides, A.; Laird, J.R.; Saba, L.; Suri, J.S. Numerical analysis of the effect of turbulence transition on the hemodynamic parameters in human coronary arteries. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2016, 6, 208–220.

- Rabbi, M.F.; Laboni, F.S.; Arafat, M.T. Computational analysis of the coronary artery hemodynamics with different anatomical variations. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2020, 19, 100314.

- Malota, Z.; Glowacki, J.; Sadowski, W.; Kostur, M. Numerical analysis of the impact of flow rate, heart rate, vessel geometry, and degree of stenosis on coronary hemodynamic indices. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2018, 18, 1–16.