E-mobility sustainability assessment is becoming more comprehensive with research integrating social aspects without focusing only on technical, economic, and/or environmental perspectives. The transportation sector is indeed one of the leading and most challenging greenhouse-gas polluters, and e-mobility is seen as one of the potential solutions; however, a social perspective must be further investigated to improve the perception of and acceptance of electric vehicles.

- electric vehicles

- social sustainability

- social perspective

- research trends

Note:All the information in this draft can be edited by authors. And the entry will be online only after authors edit and submit it.

1. Introduction

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development presented the report “Our Common Future”. They attempted to explain how important sustainability is to protect the environment for future generations and integrate social and economic progress. They also argued that governments should incorporate environmental considerations into decision-making [1]. The importance of sustainability was then expanded and was implemented in-laws, meaning countries started adopting sustainability-oriented laws [2], and at the same time, consumers became more and more aware of sustainability, mostly from the economic and environmental perspective [3]. This has also impacted the transportation sector, presenting considerable environmental, social, and economic challenges [4]. However, transport is vital from the economic perspective employing about 11 million people and generates almost 5% of the EU’s GDP [5]. However, transportation accounted for about 24% of all greenhouse gas emissions in the EU. It consequently plays a significant role in air pollution resulting in climate change due to greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions [6].

Furthermore, road transport, in particular, accounted for about 18% of all EU emissions in 2012 [7]. A European Green Deal is one of the most impactful EU priorities that aims to transform the EU into modern, resource-efficient, climate-neutral, and sustainable. Decoupling growth from material use and emissions is especially challenging for sustainable mobility—a part of which is also e-mobility.

Replacing the internal combustion vehicles with new technologies such as electric vehicles (EV) could be a step towards more sustainable transport and reduced environmental impacts [6]. When just considering the use phase, reducing polluting emissions during driving of EVs is automatically achieved by all EVs [8] as they allow zero-emission driving. However, a negative impact is also perceived for using EVs since electricity for charging can be produced from environmentally disputable sources, e.g., fossil fuels [9]. Again, EVs impact the environment and human health in the production phase and end of life cycle, particularly particulate matter formation [10]. Furthermore, EVs’ manufacturing presents a greater environmental burden with respect to gasoline cars, especially for the large use of metals, chemicals, and energy required by specific components of the electric powertrain such as the high-voltage battery [11]. Not only do EVs impact on the environment, but also on the social dimension. Onat et al. [12] argue that social impacts of alternative vehicle technologies should be further investigated to develop effective, sustainable mobility strategies. Furthermore, it is crucial to integrate the social perspective when studying electric vehicles’ impacts, as the social perspective is interlinked with the environmental one [13]. Additionally, focusing only on the environmental perspective, substantial positive or negative social impacts regarding the electric vehicle impact can be overlooked; positive, for instance, presenting reduction of noise pollution, which can be positive or negative [14], while negative, for example, presenting the potential for exploitation of child labor [15]. Some of the impacts of EVs might even have social implications as byproducts (social impacts, social costs, etc.), which can influence EV acceptance and perception as well as social welfare. Some authors also expose user experience as one of the social factors as it is far from being related only to technical aspects. Moreover, 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) defined by the United Nations (UN) to be achieved by 2030 represent a framework on which research and industry—also car manufacturers, as well as e-mobility in general—should focus in the future [16].

Inspired by the importance of social impacts of EVs, this paper presents a systematic overview of research papers related to EVs’ social aspect in a five-year period of 2015-2019. With respect to reviewed papers, it was found out that linking EVs with their impact, user perception and acceptance was already researched. However, lacking examinations of their relation to UN SDGs was identified as well as dividing them into different categories.

2. Priority Research Focus on EV Studies—Lessons Learned from a Systematic Literature Review

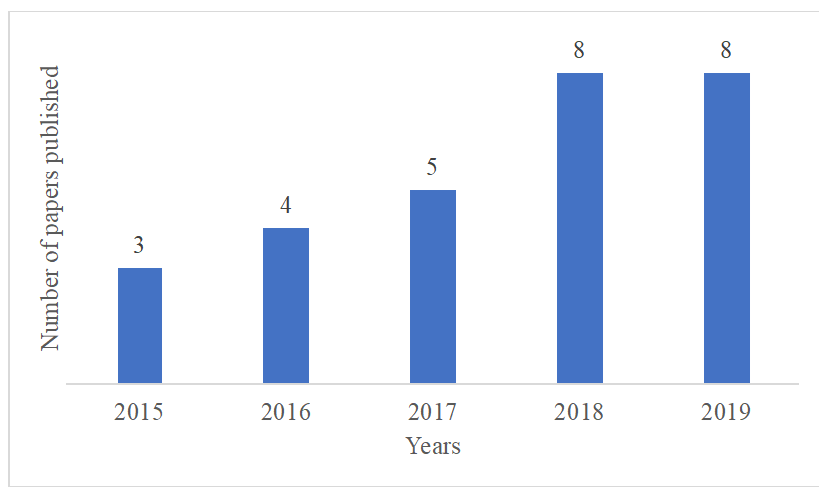

Papers published on the thematic of EVs’ social impact have recently been frequently studied. The WoS research comprehended twenty-eight scientific papers published and related on topics “electric vehicle” and “social impacts” thematic and the graph that presents the publishing frequency per year can be seen in Figure 1. It can be seen that there has been an increase in the last two years of papers published regarding the social impact of EVs, meaning that this topic gains scientific as well as political importance. In 2018 and 2019, eight papers were published on the social impact of EVs thematic, respectively, while there were five papers published in 2017, four in 2016, and only three in 2015. This can also be supported by the fact that EVs are gaining more and more of the market share, especially in China [20], and this leads to EVs being studied more and more frequently. This is also due to methods, such as social life-cycle assessment (SLCA) gaining importance and being commonly used in the last three years [21] and due to social dimension and social sustainability being studied frequently regarding the supply chains [22].

Figure 1. Published papers related to the social aspect of electric vehicles (EVs) (annual publications).

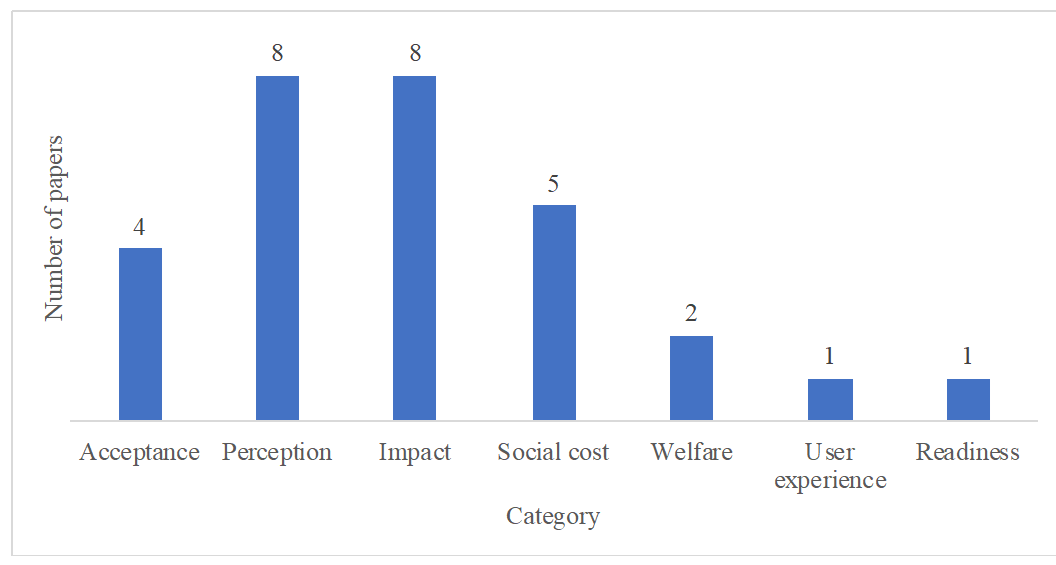

As described in the methods section, we have grouped the papers into categories based on their contribution to the field of EVs’ social impact. Figure 2 thus presents the grouping of papers, based on the categories, which are: “Acceptance”, “Perception”, “Welfare”, “Social cost”, “Impact” (using methods such as SLCA), “User experience” and “Readiness”. The papers studied evaluated or studied mentioned categories regarding the EVs.

Figure 2.

Papers divided in specific categories related to social aspects of EVs.

The authors studied the social aspect of “Acceptance”, as of 28 papers, 4 coincided into the “Acceptance” category. Onat et al. [23] studied EVs’ social acceptability, the environmental and economic impacts in the United States. Yousefi-Sahzabi et al. [24] also assessed the social acceptance of EVs in Turkey and concluded that the EVs are highly accepted and supported. Furthermore, the authors frequently focused on studying the “Perception” of EVs. For example, Brase [25] studied consumers’ perception and decision-making about electric vehicles in the U.S., while Sovacool et al. [26] studied the perception that kids have of electric vehicles and sustainable transport in Denmark and the Netherlands. They [26] found out that children overwhelmingly seem to agree on the future direction of car-based transport, but cars must be safer, more energy-efficient, and alternatively fueled.

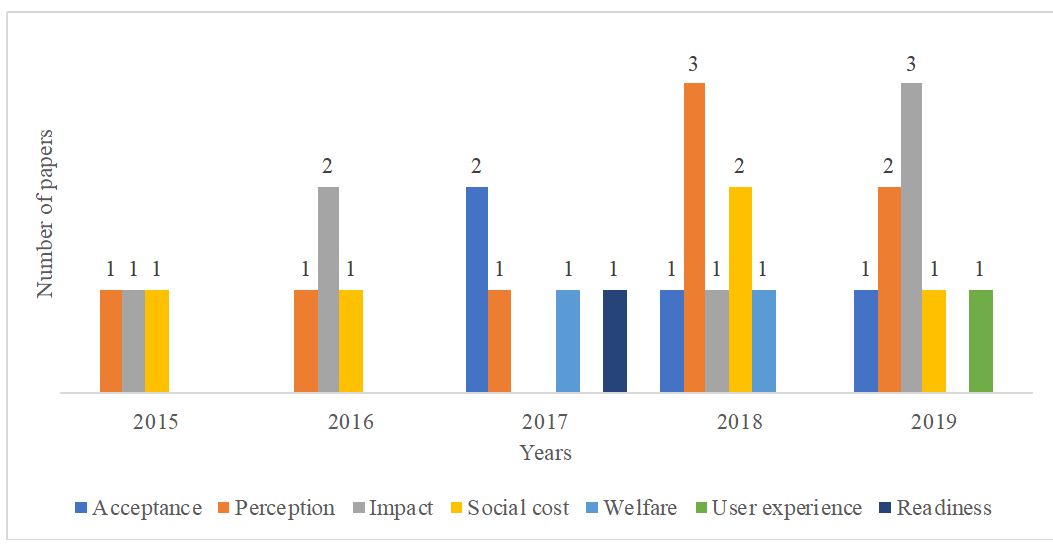

Investigating which topics are gaining or losing importance is highly important for defining future research priorities. Accordingly, the results in Figure 2 show the current research focus of studied papers divided into categories through the last five years per year, presenting which category has been given the central priority in a particular year.

Observing Figure 3, it can be seen that the year 2015 delivered papers that focused on perception, impact, and social cost of EVs. The number of impact papers has risen to two papers in 2016, while one paper related to social costs and one on the perception category was conducted in 2016. The year 2017 presented a reduction of impact studies, as none of the papers in the impact category have been published. Two papers related to category acceptance and one related to perception, welfare, and readiness respectively had been published in 2017. Furthermore, 2018 included three papers in the perception category, one in the acceptance category, two in the social cost category, and one in each impact and welfare category. The number of papers related to social impacts has once again increased in 2019, as three papers on the social impact of EVs were published in 2019, and two perception related papers were also delivered. A user experience related paper was also published in 2019, showing that user as a research focus might be more critical as a research focus in the future.

Figure 3. The research focus of papers related to social aspects of EVs included in Web of Science (WoS) in the last five years.

However, the authors allow the possibility that different social dimensions were studied and covered in published papers that were excluded from this study (e.g., papers published in journals not listed in WoS, conference papers, etc.

The authors most frequently focused on studying EVs’ social impact with a method such as SLCA (or simplified SLCA). Social impact assessment of EV was identified in 8 out of 28 papers. For instance, Onat et al. [27] used seven sustainability indicators to indicate the social, environmental, and economic impact of different vehicles, including EV and perceived EV, to be the best alternative in the long-term for reducing human health impacts and air pollution from transportation. Onat et al. [28] also evaluated the social impact of EVs, although employing a life-cycle sustainability assessment, which includes the SLCA. They also presented a framework for assessing the sustainability of EV. They perceived that the optimal vehicle distribution in the U.S., considering the socio-economic indicators, would comprise internal combustion vehicles in the majority. Albergaria de Mello Bandeira et al. [29] also assessed EVs’ sustainability in the last mile delivery and perceived several positive social impacts of EVs.

EVs social costs were investigated in 5 out of 28 papers. Newbery and Strbac [30]) evaluated the EVs regarding what is needed for battery electric vehicles to become socially cost-competitive, while Luo et al. [31] analyzed charging stations for EVs to minimize social costs, which are in both cases bigger than conventional vehicles.

Only two papers covered category welfare (one user experience and one readiness), meaning these categories were less addressed, but user experience might become more critical in the future.

The distribution of the published papers among journals has shown that most of the papers related to social aspects of EVs were published in the journal Transportation Research Part D (Transport and Environment), followed by Applied Energy and Transportation Research Part A (Policy and Practice) (Table 1).

Table 1. List of journals covering the social aspect of electric vehicles (EVs).

|

Transportation Research Part D (Transport and Environment), |

6 |

|

Applied energy |

3 |

|

Transportation Research Part A (Policy and Practice) |

3 |

|

Technological Forecasting & Social Change |

2 |

|

Energy |

2 |

|

Journal of Cleaner Production |

2 |

|

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews |

2 |

|

Other journals |

8 |

Papers included in the detailed analysis are presented in Table 2. Additionally, the geographical area of the conducted study for each paper is also shown. Moreover, the studied paper was related to 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [16].

Table 2. Research focus, category, geographical area, and relation to the sustainable development goals (SDGs) (alphabetically).

|

Paper |

Paper Focus |

Social Aspect Category |

Geographical Area |

Relation to SDGs |

|

Albergaria de Mello Bandeira et al. (2019) [29] |

Proposing a method to assess alternative strategies for the last-mile of parcel deliveries in terms of social, environmental, and economic impacts |

Impact |

Brazil (Rio de Janeiro) |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being |

|

Andwari et al. (2017) [32] |

Evaluating the technological readiness of the different elements of BEV technology |

Readiness |

- |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work, and economic growth |

|

Brase (2018) [25] |

Psychology of consumer perceptions and decisions about EVs |

Perception |

U.S.A |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work, and economic growth |

|

Cherchi (2017) [33] |

Measure the effect of both informational and normative conformity in the preference for EV |

Perception |

- |

Sustainable cities and communities |

|

Daramy-Williams et al. (2019) [34] |

Reviewing the user experience, driving EVs |

User experience |

UK |

It cannot be defined |

|

Fang et al. (2018) [35] |

Estimating marginal emission rates of electricity and the marginal price of electricity provided for charging EVs at different times of the day |

Social cost |

U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Giordano et al. (2018) [36] |

Comparing diesel and battery electric delivery vans from an environmental and economic perspective |

Impact |

EU, U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being |

|

Günther et al. (2015) [37] |

The study analyzes where jobs could be created or cut down and the other two dimensions of sustainability |

Impact |

Germany, China, EU |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Hardman et al. (2016) [38] |

The distinction between high-end adopters and low-end adopters |

Perception |

- |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Helveston et al. (2015) [39] |

Consumer preferences for conventional, hybrid electric, plug-in hybrid electric (PHEV), and battery electric (BEV) vehicle technologies |

Perception |

China, U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Herrenkind et al. (2019) [40] |

Conducting qualitative research to identify relevantly factors influencing individual acceptance of autonomously driven electric buses |

Acceptance |

Germany |

Sustainable cities and communities, Industry, innovation, and infrastructure |

|

Kershaw et al. (2018) [41] |

Assessing the contemporary ‘consumption’ of the motor-car in the context of increased uptake of EVs as part of a transition to a low carbon automobility |

Perception |

UK |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

King et al. (2019) [42] |

Investigating the effects of stereotype threat on EV drivers |

Perception |

UK |

Sustainable cities and communities |

|

Kontou et al. (2015) [43] |

Optimal electric driving range of (PHEVs) that minimizes the daily cost borne by the society when using this technology |

Social cost |

U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Industry, innovation and infrastructure |

|

Luo et al. (2018) [31] |

Proposing an optimization model for minimizing the annualized social cost of the whole EV charging system |

Social cost |

China |

Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Industry, innovation, and infrastructure |

|

Luo et al. (2019) [44] |

Proposing a comprehensive optimization model concerning the joint planning of distributed generators and EVs charging stations |

Social cost |

China |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Industry, innovation and infrastructure |

|

Newbery & Strbac (2016) [30] |

What would make EVs to become socially cost competitive |

Social cost |

UK |

Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Onat et al. (2016a) [27] |

Uncertainty-embedded dynamic life cycle sustainability assessment framework |

Impact |

U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being |

|

Onat et al. (2016b) [28] |

To advance the existing sustainability assessment framework for alternative passenger cars |

Impact |

U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being |

|

Onat et al. (2017) [23] |

Suitability of battery electric vehicles in the United States and the social acceptability of the technology |

Acceptance |

U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Affordable and clean energy |

|

Onat et al. (2019) [12] |

Presenting a novel comprehensive life cycle sustainability assessment for four different support utility EV technologies |

Impact |

Qatar |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being, Clean water and sanitation |

|

Pautasso et al. (2019) [45] |

Proposing a model for evaluating environmental, social, and economic impacts exerted by the diffusion of EVs |

Impact |

Italy |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being |

|

Shao et al. (2017) [46] |

Social welfare of monopoly and duopoly of EVs and gasoline cars |

Welfare |

- |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities |

|

Sovacool et al. (2018) [47] |

Assessing of the demographics of electric mobility and stated preferences for EV |

Perception |

Nordic region |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Sovacool et al. (2019) [26] |

Assessing how schoolchildren between 9 and 13 years of age think about electric mobility |

Perception |

Denmark, Netherlands |

Sustainable cities and communities |

|

Wang et al. (2019) [48] |

Explore the potential factors that affect consumers’ acceptance of EVs in Shanghai |

Acceptance |

Shanghai |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities |

|

Yousefi-Sahzabi et al. (2017) [24] |

Social acceptance of low-carbon energy technologies in Turkey and the current status of the energy sector from a social perspective related to EVs |

Acceptance |

Turkey |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Affordable and clean energy |

|

Zheng et al. (2018) [49] |

Investigating the impact of EV manufacturing- and society-related factors on balance among manufacturer profits, environmental impact, and social welfare. |

Welfare |

China |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Paper |

Paper Focus |

Social Aspect Category |

Geographical Area |

Relation to SDGs |

|

Albergaria de Mello Bandeira et al. (2019) [29] |

Proposing a method to assess alternative strategies for the last-mile of parcel deliveries in terms of social, environmental, and economic impacts |

Impact |

Brazil (Rio de Janeiro) |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being |

|

Andwari et al. (2017) [32] |

Evaluating the technological readiness of the different elements of BEV technology |

Readiness |

- |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work, and economic growth |

|

Brase (2018) [25] |

Psychology of consumer perceptions and decisions about EVs |

Perception |

U.S.A |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work, and economic growth |

|

Cherchi (2017) [33] |

Measure the effect of both informational and normative conformity in the preference for EV |

Perception |

- |

Sustainable cities and communities |

|

Daramy-Williams et al. (2019) [34] |

Reviewing the user experience, driving EVs |

User experience |

UK |

It cannot be defined |

|

Fang et al. (2018) [35] |

Estimating marginal emission rates of electricity and the marginal price of electricity provided for charging EVs at different times of the day |

Social cost |

U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Giordano et al. (2018) [36] |

Comparing diesel and battery electric delivery vans from an environmental and economic perspective |

Impact |

EU, U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being |

|

Günther et al. (2015) [37] |

The study analyzes where jobs could be created or cut down and the other two dimensions of sustainability |

Impact |

Germany, China, EU |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Hardman et al. (2016) [38] |

The distinction between high-end adopters and low-end adopters |

Perception |

- |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Helveston et al. (2015) [39] |

Consumer preferences for conventional, hybrid electric, plug-in hybrid electric (PHEV), and battery electric (BEV) vehicle technologies |

Perception |

China, U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Herrenkind et al. (2019) [40] |

Conducting qualitative research to identify relevantly factors influencing individual acceptance of autonomously driven electric buses |

Acceptance |

Germany |

Sustainable cities and communities, Industry, innovation, and infrastructure |

|

Kershaw et al. (2018) [41] |

Assessing the contemporary ‘consumption’ of the motor-car in the context of increased uptake of EVs as part of a transition to a low carbon automobility |

Perception |

UK |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

King et al. (2019) [42] |

Investigating the effects of stereotype threat on EV drivers |

Perception |

UK |

Sustainable cities and communities |

|

Kontou et al. (2015) [43] |

Optimal electric driving range of (PHEVs) that minimizes the daily cost borne by the society when using this technology |

Social cost |

U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Industry, innovation and infrastructure |

|

Luo et al. (2018) [31] |

Proposing an optimization model for minimizing the annualized social cost of the whole EV charging system |

Social cost |

China |

Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Industry, innovation, and infrastructure |

|

Luo et al. (2019) [44] |

Proposing a comprehensive optimization model concerning the joint planning of distributed generators and EVs charging stations |

Social cost |

China |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Industry, innovation and infrastructure |

|

Newbery & Strbac (2016) [30] |

What would make EVs to become socially cost competitive |

Social cost |

UK |

Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Onat et al. (2016a) [27] |

Uncertainty-embedded dynamic life cycle sustainability assessment framework |

Impact |

U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being |

|

Onat et al. (2016b) [28] |

To advance the existing sustainability assessment framework for alternative passenger cars |

Impact |

U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being |

|

Onat et al. (2017) [23] |

Suitability of battery electric vehicles in the United States and the social acceptability of the technology |

Acceptance |

U.S.A. |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Affordable and clean energy |

|

Onat et al. (2019) [12] |

Presenting a novel comprehensive life cycle sustainability assessment for four different support utility EV technologies |

Impact |

Qatar |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being, Clean water and sanitation |

|

Pautasso et al. (2019) [45] |

Proposing a model for evaluating environmental, social, and economic impacts exerted by the diffusion of EVs |

Impact |

Italy |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Good health and well-being |

|

Shao et al. (2017) [46] |

Social welfare of monopoly and duopoly of EVs and gasoline cars |

Welfare |

- |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities |

|

Sovacool et al. (2018) [47] |

Assessing of the demographics of electric mobility and stated preferences for EV |

Perception |

Nordic region |

Climate action, Sustainable cities and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

|

Sovacool et al. (2019) [26] |

Assessing how schoolchildren between 9 and 13 years of age think about electric mobility |

Perception |

Denmark, Netherlands |

Sustainable cities and communities |

|

Wang et al. (2019) [48] |

Explore the potential factors that affect consumers’ acceptance of EVs in Shanghai |

Acceptance |

Shanghai |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities |

|

Yousefi-Sahzabi et al. (2017) [24] |

Social acceptance of low-carbon energy technologies in Turkey and the current status of the energy sector from a social perspective related to EVs |

Acceptance |

Turkey |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth, Affordable and clean energy |

|

Zheng et al. (2018) [49] |

Investigating the impact of EV manufacturing- and society-related factors on balance among manufacturer profits, environmental impact, and social welfare. |

Welfare |

China |

Climate action, Sustainable cities, and communities, Decent work and economic growth |

Table 2 presents that most of the studied papers are national studies related to one country or even region only (20 papers). Only four included more than one country and could be identified as international studies. The remaining four papers did not specify their geographical orientation.

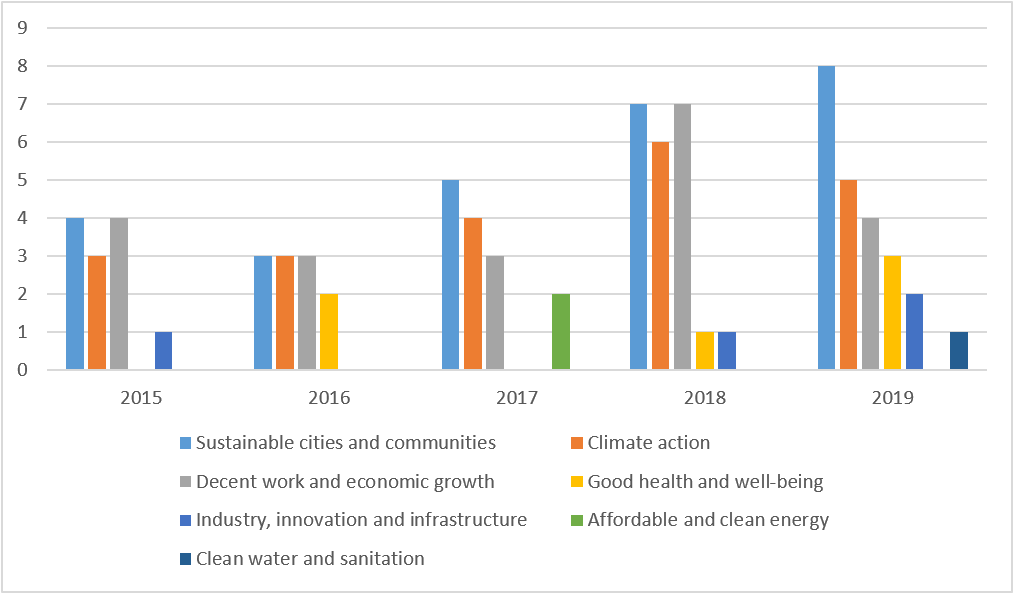

Table 2 and Figure 4 display that most papers contribute or are related to one or more UN SDGs. Most identified SDG was the relation with “sustainable cities and communities” (96.43% of papers are related to this goal), “climate action” (75% of papers are related to this goal), and “decent work and economic growth” (75% of papers are related to this goal). It is seen in Figure 4 that “sustainable cities and communities” was one of the priorities through all studied years but rocketed in 2019 to be much more represented than other SDGs.

Figure 4. Relation and focus of studied papers towards UN sustainable development goals.

Papers are less related to SDGs such as “affordable and clean energy” (only 3.57% of papers related), “good health and well-being” (17.86% of papers related), “clean water and sanitation” (only 3.57% of papers related). “industry, innovation and infrastructure” (14.29% of papers related) seem to have moderate importance, and research focus in some cases can be associated with this goal as well, mainly due to investigating charging infrastructure associated with EVs.

Almost all papers are related to more than one SDG. The study of Albergaria de Mello Bandeira et al. [29] was related to goals “climate action”, “sustainable cities and communities”, “decent work and economic growth,” and “good health and well-being”. As the authors focused on proposing a method to assess alternative strategies for the last-mile of parcel deliveries, they also focused on the impact on worker’s health, and the paper is therefore related to “good health and well-being”. The goal is to ensure healthy lives, and this can be done by first evaluating and then reducing the impact of different factors on worker’s health. Relation with “climate action” can also be identified since it assesses the environmental impacts of EV use and it takes urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. Albergaria de Mello Bandeira et al. [29] study further relates to “decent work and economic growth”, which aims to promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth. As they assess different delivery strategies from an economic perspective, they support sustainable economic development. The paper also relates to “sustainable cities and communities”, the goal of which is to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. They assess postal deliveries in Rio de Janeiro from all three sustainability perspectives to make cities safe and sustainable.

References

- WCED-World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxfor University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Chaturvedi, U.; Sharma, M.; Dangayach, G.S.; Sarkar, P. Evolution and adoption of sustainable practices in the pharmaceu-tical industry: An overview with an Indian perspective. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 1358–1369.

- Garcia, S.; Cordeiro, A.; Nääs, I.D.A.; Neto, P.L.D.O.C. The sustainability awareness of Brazilian consumers of cotton clothing. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1490–1502, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.069.

- Currie, G.; Truong, L.T.; De Gruyter, C. Regulatory structures and their impact on the sustainability performance of public transport in world cities. Transp. Econ. 2018, 69, 494–500, doi:10.1016/j.retrec.2018.02.001.

- European Commission. 2018. Transport in the European Union: Current Trends and Issues. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transport/sites/transport/files/2018-transport-in-the-eu-current-trends-and-issues.pdf. (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Kumar, R.R.; Alok, K. Adoption of electric vehicle: A literature review and prospects for sustainability. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119911, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119911.

- European Commission. 2012. Road Transport: A Change of Gear. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transport/sites/transport/files/modes/road/doc/broch-road-transport_en.pdf. (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Raugei, M.; Winfield, P. Prospective LCA of the production and EoL recycling of a novel type of Li-ion battery for electric vehicles. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 926–932, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.237.

- Petrauskienè, K.; Skvarnavičiūtė, M.; Dvarionienė, J. Comparative environmental life cycle assessment of electric and con-ventional vehicles in Lithuania. Clean. Prod. 2020, 119042, doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119042.

- Burchart-Korol, D.; Jursova, S.; Folęga, P.; Korol, J.; Pustejovska, P.; Blaut, A. Environmental life cycle assessment of electric vehicles in Poland and the Czech Republic. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 476–487, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.145.

- Del Pero, F.; Delogu, M.; Pierini, M. Life Cycle Assessment in the automotive sector: A comparative case study of Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) and electric car. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2018, 12, 521–537, doi:10.1016/j.prostr.2018.11.066.

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Aboushaqrah, N.N.M.; Jabbar, R. Energy 2019, 250, 461–477.

- Jawahir, I.S.; Dillon, O.W.; Rouch, K.E.; Joshi, K.J.; Venkatachalam, A.; Jaafar, I.H. Total life-cycle considerations in product design for sustainability: A framework for comprehensive evaluation. In Proceedings of the 10th International Research/Expert Conference “Trends in the Development of Machinery and Associated Technology” TMT, Barcelona, Spain, 11–15 September 2006.

- Pardo-Ferreira, M.C.; Rubio-Romero, J.C.; Galindo-Reyes, F.C.; Arquillos, A.L. Work-related road safety: The impact of the low noise levels produced by electric vehicles according to experienced drivers. Sci. 2020, 121, 580–588, doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2019.02.021.

- The Methodological Sheets for Sub-Categories in Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) United Nations Environment Pro-gramme and SETAC. Available online: https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/S-LCA_methodological_sheets_11.11.13.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- United Nations (UN). Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222, doi:10.1111/1467-8551.00375.

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228, doi:10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5.

- Knez, M.; Obrecht, M. Electric Vehicles Infrastructure Related Drivers’ Needs and Preferences; Faculty of Logistics: Celje, Slovenia, 2015. (In Slovenian).

- Zheng, J.; Sun, X.; Jia, L.; Zhou, Y. Electric passenger vehicles sales and carbon dioxide emission reduction potential in China’s leading markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118607, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118607.

- Costa, D.; Quinteiro, P.; Dias, A. A systematic review of life cycle sustainability assessment: Current state, methodological challenges, and implementation issues. Total. Environ. 2019, 686, 774–787, doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.435.

- D’Eusanio, M.; Zamagni, A.; Petti, L. Social sustainability and supply chain management: Methods and tools. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 178–189, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.323.

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Noori, M.; Zhao, Y.; Tatari, O.; Chester, M. Exploring the suitability of electric vehicles in the United States. Energy 2017, 121, 631–642, doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.01.035.

- Yousefi-Sahzabi, A.; Unlu-Yucesoy, E.; Sasaki, K.; Yuosefi, H.; Widiatmojo, A.; Sugai, Y. Turkish challenges for low-carbon society: Current status, government policies and social acceptance. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 596–608, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.090.

- Brase, G.L. What Would It Take to Get You into an Electric Car? Consumer Perceptions and Decision Making about Electric Vehicles. Psychol. 2018, 153, 214–236, doi:10.1080/00223980.2018.1511515.

- Sovacool, B.K.; Kester, J.; Heida, V. Cars and kids: Childhood perceptions of electric vehicles and sustainable transport in Denmark and the Netherlands. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 182–192, doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2019.04.006.

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Tatari, O. Uncertainty-embedded dynamic life cycle sustainability assessment framework: An ex-ante perspective on the impacts of alternative vehicle options. Energy 2016, 112, 715–728, doi:10.1016/j.energy.2016.06.129.

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Tatari, O.; Zheng, Q.P. Combined application of multi-criteria optimization and life-cycle sus-tainability assessment for optimal distribution of alternative passenger cars in U.S. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 291–307.

- Albergaria de Mello Bandeira, R.; Vasconcelos Goes, G.; Schmitz Gonçalves, D.N.; Almeida D’Agosto, M.; Oliveira, C.M. Electric vehicles in the last mile of urban freight transportation: A sustainability assessment of postal deliveries in Rio de Janeiro-Brazil. Res. Part D 2019, 67, 491–502.

- Newbery, D.M.; Strbac, G. What is needed for battery electric vehicles to become socially cost competitive? Transp. 2016, 5, 1–11, doi:10.1016/j.ecotra.2015.09.002.

- Luo, L.; Gu, W.; Zhou, S.; Huang, H.; Gao, S.; Han, J.; Wu, Z.; Dou, X. Optimal planning of electric vehicle charging stations comprising multi-types of charging facilities. Energy 2018, 226, 1087–1099, doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.06.014.

- Andwari, A.M.; Pesiridis, A.; Rajoo, S.; Martinez-Botas, R.; Esfahanian, V. A review of Battery Electric Vehicle technology and readiness levels. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 414–430, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.138.

- Cherchi, E. A stated choice experiment to measure the effect of informational and normative conformity in the preference for electric vehicles. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2017, 100, 88–104, doi:10.1016/j.tra.2017.04.009.

- Daramy-Williams, E.; Anable, J.; Grant-Muller, S. A systematic review of the evidence on plug-in electric vehicle user experi-ence. Res. Part D 2019, 71, 22–36.

- Fang, Y.; Asche, F.; Novan, K. The costs of charging Plug-in Electric Vehicles (PEVs): Within day variation in emissions and electricity prices. Energy Econ. 2018, 69, 196–203, doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2017.11.011.

- Giordano, A.; Fischbeck, P.; Matthews, H.S. Environmental and economic comparison of diesel and battery electric delivery vans to inform city logistics fleet replacement strategies. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 64, 216–229, doi:10.1016/j.trd.2017.10.003.

- Günther, H.-O.; Kannegiesser, M.; Autenrieb, N. The role of electric vehicles for supply chain sustainability in the automotive industry. Clean. Prod. 2015, 90, 220–233, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.058.

- Hardman, S.; Shiu, E.; Steinberger-Wilckens, R. Comparing high-end and low-end early adopters of battery electric vehicles. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2016, 88, 40–57, doi:10.1016/j.tra.2016.03.010.

- Helveston, J.P.; Liu, Y.; Feit, E.M.; Fuchs, E.; Klampfl, E.; Michalek, J.J. Will subsidies drive electric vehicle adoption? Measuring consumer preferences in the U.S. and China. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2015, 73, 96–112, doi:10.1016/j.tra.2015.01.002.

- Herrenkind, B.; Brendel, A.B.; Nastjuk, I.; Greve, M.; Kolbe, L.M. Investigating end-user acceptance of autonomous electric buses to accelerate diffusion. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 74, 255–276, doi:10.1016/j.trd.2019.08.003.

- Kershaw, J.; Berkeley, N.; Jarvis, D.; Begley, J. A feeling for change: Exploring the lived and unlived experiences of drivers to inform a transition to an electric automobility. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 65, 674–686, doi:10.1016/j.trd.2018.10.011.

- King, N.; Burgess, M.; Harris, M. Electric vehicle drivers use better strategies to counter stereotype threat linked to pro-technology than to pro-environmental identities. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 60, 440–452, doi:10.1016/j.trf.2018.10.031.

- Kontou, E.; Yin, Y.; Lin, Z. Socially optimal electric driving range of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 39, 114–125, doi:10.1016/j.trd.2015.07.002.

- Luo, L.; Gu, W.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, S. Joint planning of distributed generation and electric vehicle charging stations considering real-time charging navigation. Energy 2019, 242, 1274–1284, doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.03.162.

- Pautasso, E.; Osella, M.; Caroleo, B.R.D. Addressing the Sustainability Issue in Smart Cities: A Comprehensive Model for Evaluating the Impacts of Electric Vehicle Diffusion. Systems 2019, 7, 29, doi:10.3390/systems7020029.

- Shao, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M. Subsidy scheme or price discount scheme? Mass adoption of electric vehicles under different market structures. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 262, 1181–1195, doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2017.04.030.

- Sovacool, B.K.; Kester, J.; Noel, L.; De Rubens, G.Z. The demographics of decarbonizing transport: The influence of gender, education, occupation, age, and household size on electric mobility preferences in the Nordic region. Environ. Chang. 2018, 52, 86–100, doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.06.008.

- Wang, N.; Tang, L.; Pan, H. Analysis of public acceptance of electric vehicles: An empirical study in Shanghai. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 126, 284–291, doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.09.011.

- Zheng, X.; Lin, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, D.-F.; Llopis-Albert, C.; Zeng, S. Manufacturing Decisions and Government Subsidies for Electric Vehicles in China: A Maximal Social Welfare Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 672, doi:10.3390/su10030672.

References

- WCED-World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxfor University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Chaturvedi, U.; Sharma, M.; Dangayach, G.S.; Sarkar, P. Evolution and adoption of sustainable practices in the pharmaceu-tical industry: An overview with an Indian perspective. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 1358–1369.

- Garcia, S.; Cordeiro, A.; Nääs, I.D.A.; Neto, P.L.D.O.C. The sustainability awareness of Brazilian consumers of cotton clothing. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1490–1502, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.069.

- Currie, G.; Truong, L.T.; De Gruyter, C. Regulatory structures and their impact on the sustainability performance of public transport in world cities. Transp. Econ. 2018, 69, 494–500, doi:10.1016/j.retrec.2018.02.001.

- European Commission. 2018. Transport in the European Union: Current Trends and Issues. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transport/sites/transport/files/2018-transport-in-the-eu-current-trends-and-issues.pdf. (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Kumar, R.R.; Alok, K. Adoption of electric vehicle: A literature review and prospects for sustainability. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119911, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119911.

- European Commission. 2012. Road Transport: A Change of Gear. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transport/sites/transport/files/modes/road/doc/broch-road-transport_en.pdf. (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Raugei, M.; Winfield, P. Prospective LCA of the production and EoL recycling of a novel type of Li-ion battery for electric vehicles. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 926–932, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.237.

- Petrauskienè, K.; Skvarnavičiūtė, M.; Dvarionienė, J. Comparative environmental life cycle assessment of electric and con-ventional vehicles in Lithuania. Clean. Prod. 2020, 119042, doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119042.

- Burchart-Korol, D.; Jursova, S.; Folęga, P.; Korol, J.; Pustejovska, P.; Blaut, A. Environmental life cycle assessment of electric vehicles in Poland and the Czech Republic. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 476–487, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.145.

- Del Pero, F.; Delogu, M.; Pierini, M. Life Cycle Assessment in the automotive sector: A comparative case study of Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) and electric car. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2018, 12, 521–537, doi:10.1016/j.prostr.2018.11.066.

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Aboushaqrah, N.N.M.; Jabbar, R. Energy 2019, 250, 461–477.

- Jawahir, I.S.; Dillon, O.W.; Rouch, K.E.; Joshi, K.J.; Venkatachalam, A.; Jaafar, I.H. Total life-cycle considerations in product design for sustainability: A framework for comprehensive evaluation. In Proceedings of the 10th International Research/Expert Conference “Trends in the Development of Machinery and Associated Technology” TMT, Barcelona, Spain, 11–15 September 2006.

- Pardo-Ferreira, M.C.; Rubio-Romero, J.C.; Galindo-Reyes, F.C.; Arquillos, A.L. Work-related road safety: The impact of the low noise levels produced by electric vehicles according to experienced drivers. Sci. 2020, 121, 580–588, doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2019.02.021.

- The Methodological Sheets for Sub-Categories in Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) United Nations Environment Pro-gramme and SETAC. Available online: https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/S-LCA_methodological_sheets_11.11.13.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- United Nations (UN). Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222, doi:10.1111/1467-8551.00375.

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228, doi:10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5.

- Knez, M.; Obrecht, M. Electric Vehicles Infrastructure Related Drivers’ Needs and Preferences; Faculty of Logistics: Celje, Slovenia, 2015. (In Slovenian).

- Zheng, J.; Sun, X.; Jia, L.; Zhou, Y. Electric passenger vehicles sales and carbon dioxide emission reduction potential in China’s leading markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118607, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118607.

- Costa, D.; Quinteiro, P.; Dias, A. A systematic review of life cycle sustainability assessment: Current state, methodological challenges, and implementation issues. Total. Environ. 2019, 686, 774–787, doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.435.

- D’Eusanio, M.; Zamagni, A.; Petti, L. Social sustainability and supply chain management: Methods and tools. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 178–189, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.323.

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Noori, M.; Zhao, Y.; Tatari, O.; Chester, M. Exploring the suitability of electric vehicles in the United States. Energy 2017, 121, 631–642, doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.01.035.

- Yousefi-Sahzabi, A.; Unlu-Yucesoy, E.; Sasaki, K.; Yuosefi, H.; Widiatmojo, A.; Sugai, Y. Turkish challenges for low-carbon society: Current status, government policies and social acceptance. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 596–608, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.090.

- Brase, G.L. What Would It Take to Get You into an Electric Car? Consumer Perceptions and Decision Making about Electric Vehicles. Psychol. 2018, 153, 214–236, doi:10.1080/00223980.2018.1511515.

- Sovacool, B.K.; Kester, J.; Heida, V. Cars and kids: Childhood perceptions of electric vehicles and sustainable transport in Denmark and the Netherlands. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 182–192, doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2019.04.006.

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Tatari, O. Uncertainty-embedded dynamic life cycle sustainability assessment framework: An ex-ante perspective on the impacts of alternative vehicle options. Energy 2016, 112, 715–728, doi:10.1016/j.energy.2016.06.129.

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Tatari, O.; Zheng, Q.P. Combined application of multi-criteria optimization and life-cycle sus-tainability assessment for optimal distribution of alternative passenger cars in U.S. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 291–307.

- Albergaria de Mello Bandeira, R.; Vasconcelos Goes, G.; Schmitz Gonçalves, D.N.; Almeida D’Agosto, M.; Oliveira, C.M. Electric vehicles in the last mile of urban freight transportation: A sustainability assessment of postal deliveries in Rio de Janeiro-Brazil. Res. Part D 2019, 67, 491–502.

- Newbery, D.M.; Strbac, G. What is needed for battery electric vehicles to become socially cost competitive? Transp. 2016, 5, 1–11, doi:10.1016/j.ecotra.2015.09.002.

- Luo, L.; Gu, W.; Zhou, S.; Huang, H.; Gao, S.; Han, J.; Wu, Z.; Dou, X. Optimal planning of electric vehicle charging stations comprising multi-types of charging facilities. Energy 2018, 226, 1087–1099, doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.06.014.

- Andwari, A.M.; Pesiridis, A.; Rajoo, S.; Martinez-Botas, R.; Esfahanian, V. A review of Battery Electric Vehicle technology and readiness levels. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 414–430, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.138.

- Cherchi, E. A stated choice experiment to measure the effect of informational and normative conformity in the preference for electric vehicles. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2017, 100, 88–104, doi:10.1016/j.tra.2017.04.009.

- Daramy-Williams, E.; Anable, J.; Grant-Muller, S. A systematic review of the evidence on plug-in electric vehicle user experi-ence. Res. Part D 2019, 71, 22–36.

- Fang, Y.; Asche, F.; Novan, K. The costs of charging Plug-in Electric Vehicles (PEVs): Within day variation in emissions and electricity prices. Energy Econ. 2018, 69, 196–203, doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2017.11.011.

- Giordano, A.; Fischbeck, P.; Matthews, H.S. Environmental and economic comparison of diesel and battery electric delivery vans to inform city logistics fleet replacement strategies. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 64, 216–229, doi:10.1016/j.trd.2017.10.003.

- Günther, H.-O.; Kannegiesser, M.; Autenrieb, N. The role of electric vehicles for supply chain sustainability in the automotive industry. Clean. Prod. 2015, 90, 220–233, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.058.

- Hardman, S.; Shiu, E.; Steinberger-Wilckens, R. Comparing high-end and low-end early adopters of battery electric vehicles. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2016, 88, 40–57, doi:10.1016/j.tra.2016.03.010.

- Helveston, J.P.; Liu, Y.; Feit, E.M.; Fuchs, E.; Klampfl, E.; Michalek, J.J. Will subsidies drive electric vehicle adoption? Measuring consumer preferences in the U.S. and China. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2015, 73, 96–112, doi:10.1016/j.tra.2015.01.002.

- Herrenkind, B.; Brendel, A.B.; Nastjuk, I.; Greve, M.; Kolbe, L.M. Investigating end-user acceptance of autonomous electric buses to accelerate diffusion. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 74, 255–276, doi:10.1016/j.trd.2019.08.003.

- Kershaw, J.; Berkeley, N.; Jarvis, D.; Begley, J. A feeling for change: Exploring the lived and unlived experiences of drivers to inform a transition to an electric automobility. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 65, 674–686, doi:10.1016/j.trd.2018.10.011.

- King, N.; Burgess, M.; Harris, M. Electric vehicle drivers use better strategies to counter stereotype threat linked to pro-technology than to pro-environmental identities. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 60, 440–452, doi:10.1016/j.trf.2018.10.031.

- Kontou, E.; Yin, Y.; Lin, Z. Socially optimal electric driving range of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 39, 114–125, doi:10.1016/j.trd.2015.07.002.

- Luo, L.; Gu, W.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, S. Joint planning of distributed generation and electric vehicle charging stations considering real-time charging navigation. Energy 2019, 242, 1274–1284, doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.03.162.

- Pautasso, E.; Osella, M.; Caroleo, B.R.D. Addressing the Sustainability Issue in Smart Cities: A Comprehensive Model for Evaluating the Impacts of Electric Vehicle Diffusion. Systems 2019, 7, 29, doi:10.3390/systems7020029.

- Shao, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M. Subsidy scheme or price discount scheme? Mass adoption of electric vehicles under different market structures. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 262, 1181–1195, doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2017.04.030.

- Sovacool, B.K.; Kester, J.; Noel, L.; De Rubens, G.Z. The demographics of decarbonizing transport: The influence of gender, education, occupation, age, and household size on electric mobility preferences in the Nordic region. Environ. Chang. 2018, 52, 86–100, doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.06.008.

- Wang, N.; Tang, L.; Pan, H. Analysis of public acceptance of electric vehicles: An empirical study in Shanghai. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 126, 284–291, doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.09.011.

- Zheng, X.; Lin, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, D.-F.; Llopis-Albert, C.; Zeng, S. Manufacturing Decisions and Government Subsidies for Electric Vehicles in China: A Maximal Social Welfare Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 672, doi:10.3390/su10030672.