Mares are seasonal polyestric. The morphology of the healthy equine endometrium is influenced by the season of the year, the stage of the endometrial cycle, as well as the presence of endometrial diseases. The latter have an impact on the wellbeing of individual mares and can also inflict major financial losses for the horse breeding industry. The microscopic examination of an endometrial biopsy is an important diagnostic tool, since it can also detect subclinical diseases. This review provides an overview about morphological and molecular features of the healthy and diseased equine endometrium. It reviews the diagnostic findings of inflammatory and degenerative endometrial disease of mares, as well as the current state of knowledge regarding their cellular and molecular pathogenesis. It further shows that the comparative evaluation of morphological features and molecular characteristics of the healthy and diseased equine endometrium is an important prerequisite for the identification of disease-associated molecular markers, which in turn will facilitate the development of diagnostic and predictive biomarkers, as well as novel prophylactic and therapeutic options. Although currently numerous molecular data are already available, future studies are required to establish their translation into clinical practice.

- Equine

- Endometrium

- Health

- Disease

- Pathophysiology

- Molecular Features

- Mare

- Endometrial biopsy

1.Introduction

Overview

Mares are seasonal polyestric and the endometrial morphology is influenced by the season of the year [1][2][3][4], external factors such as lightening and temperature [3] as well as the stage of the endometrial cycle [1][2]. In the Northern hemisphere, the breeding season during late spring and summer and the winter anestrus are connected by the spring and autumn transitional periods [3][4].

Endometrial diseases of mares are an important cause of subfertility [1][2][5] and can inflict major financial losses for the horse breeding industry. Endometrial diseases include endometrosis (synonym: periglandular fibrosis), endometritis, glandular differentiation disorders, and angiosis (synonym: angiosclerosis) as well as their subtypes [1][2][4][5][6][7]. The concurrent presence of several endometrial diseases in an individual mare is a common finding [1][5]. Endometrosis is characterized by periglandular fibrosis together with functional alterations of epithelial cells lining altered glands [5][7]. Endometrosis should not be confused with endometriosis, that represents a separate disease. In contrast to equine endometrosis, endometriosis is a disease of women and menstruating primates and is characterized by the presence of endometrial tissue within the serosa of the abdominal or pelvic cavities [7]. As a physiological reaction, mating or breeding evokes transient inflammation with a duration of less than 72 hrs [5][8][9]. Some mares, however, develop persisting post-breeding endometritis; these are referred to as “susceptible mares” [9][10].

The microscopic examination of an endometrial biopsy is an important diagnostic tool, since it can detect all types of endometrial diseases including subclinical diseases [5]. Moreover, it allows to determine the stage of the endometrial cycle [2][11]. For routine diagnostic investigations, the endometrial biopsy should be placed in fixative immediately after its collection; for fixation 10% buffered formalin is usually used.

The incidence and degree of some endometrial diseases are influenced by factors of the mare such as age and numbers of parturitions [5][6][7][12]. A statistically significant association exists between an older age of the mare and a higher incidence, as well as an increased degree of endometrosis [5][12][13]. The frequency of occurrence and severity of angiosclerosis rises with an advanced age of the mare and an increased number of foalings [6][13]. Microscopic findings in the endometrial biopsy of a mare, however, need to be interpreted under consideration of signalment of the mare, clinical history and season of the year [2][4][5][13]. In regard to the latter, glandular maldifferentiation is only of clinical relevance when it is diagnosed in an endometrial biopsy collected during the breeding season [4][13].

Based on the detection of certain microscopic findings, i.e. incidence and degree of endometritis, periglandular fibrosis and lymphatic lacunae, as well as endometrial atrophy during the breeding season, together with the length of barrenness, the categorization scheme of Kenney and Doig [1] is used for prognostication of the fertility of an individual mare. Subsequently, glandular maldifferentiation [13][14][15], angiosclerosis [6][13][16], subtype of endometrosis [5][17], older age of the mare [5][13] and a previous long-term use of the mare in athletic performances [18] have been revealed as further factors of reduced fertility.

The pathogenesis of some endometrial diseases such as nonsuppurative endometritis [5][19] and endometrosis [5][7][20] has still not been revealed in detail. No routinely available treatment exists for endometrosis [7][20]. Moreover, nonsuppurative endometritis often persists despite treatment [5][10]. Notably, endometrial neoplasia is a rare finding in mares [21].

Over the last years, scientific investigations on equine endometrial pathology focused on the characterization of disease-associated cellular and molecular mechanisms [15][17][19][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32]. Obtained data have diagnostic value and will assist to gain further insights into the molecular pathogenesis of endometrial diseases [15][17][19][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32]. In addition, they will likely help to design novel prophylactic regimes and treatment options [20]. Certain molecular markers have the be considered as potential biomarkers for equine endometrial health and disease, since they identify morphological and functional cellular alterations associated with endometrial diseases [15][17][23][24][25][26][27][29][30][31][32] and their cellular expression patterns can be visualized and quantified using immunohistochemistry [17][24][25][29][30][32][33]. For example, unphysiological expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors predicts altered hormonal responsiveness of the equine endometrium [17][24]. Abnormalities of the basement membrane, that can be detected by laminin immunostaining, indicate alterations in paracrine interactions between glandular epithelial and stromal cells and may result in unphysiological cellular responses to hormonal stimulation [24]. Changes in the physiological immunoreaction for intermediate and contractile filaments and associated proteins are consistent with an abnormal cellular differentiation [24][31][32]. Deviations in the expression of secretory proteins by glandular epithelia will likely cause alterations in the composition of the uterine milk as essential nutrition of the early equine conceptus [17][25]. Changes in the immunostaining for components of the innate immune defense, i.e. β-defensin and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1, suggest alterations of endometrial immunity mechanisms [29][30].

2. Conclusions

Conclusions

The combined evaluation of morphological findings and associated molecular features indicates that some examined molecular markers have the potential to serve as biomarkers for endometrial health and disease [34]. A biomarker is a biological parameter that can be objectively evaluated and indicates a normal or abnormal biological process or a response to an intervention, e.g. an immunohistochemical marker with diagnostic or prognostic value or merit for the prediction of a treatment response [35][36].

In the equine endometrium, molecules with potential to serve as biomarkers arinclude estrogen and progesterone receptors, the intermediate and contractile filaments vimentin, desmin and α-smooth muscle actin, the actin filament associated protein calponin, glandular secre, secretory proteins (uteroglobin, uterocalin, uteroferrin) as components of the uterine milk, basement membrane proteins, as well as β-defensin and indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase as and components of the innate immune defense [34]. The comparative assessment of molecular markers within the healthy and diseased equine endometrium will likely help to identify and quantify cellular dysfunctions associated with endometrial diseases and their subtypes [34]. For this, immunohistochemistry seems to be the most appropriate diagnostic tool, since it allows the detection of the proposed biomarkers in the context of tissue morphology and allows an objective measurement of their expression levels [34]. Obtained data could assist to more precisely estimate the fertility prognosis of an individual mare [34]. In addition, they are a prerequisite for the development of novel prophylactic regimes and treatment options [20][34]. In this regard, Mambelli et al. [20] observed that the implantation of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells in the endometrium of mares was associated with molecular changes in endometrotic areas towards the physiological phenotype of healthy glands. Additional studies are required to establish the translation of research data into clinical practice.

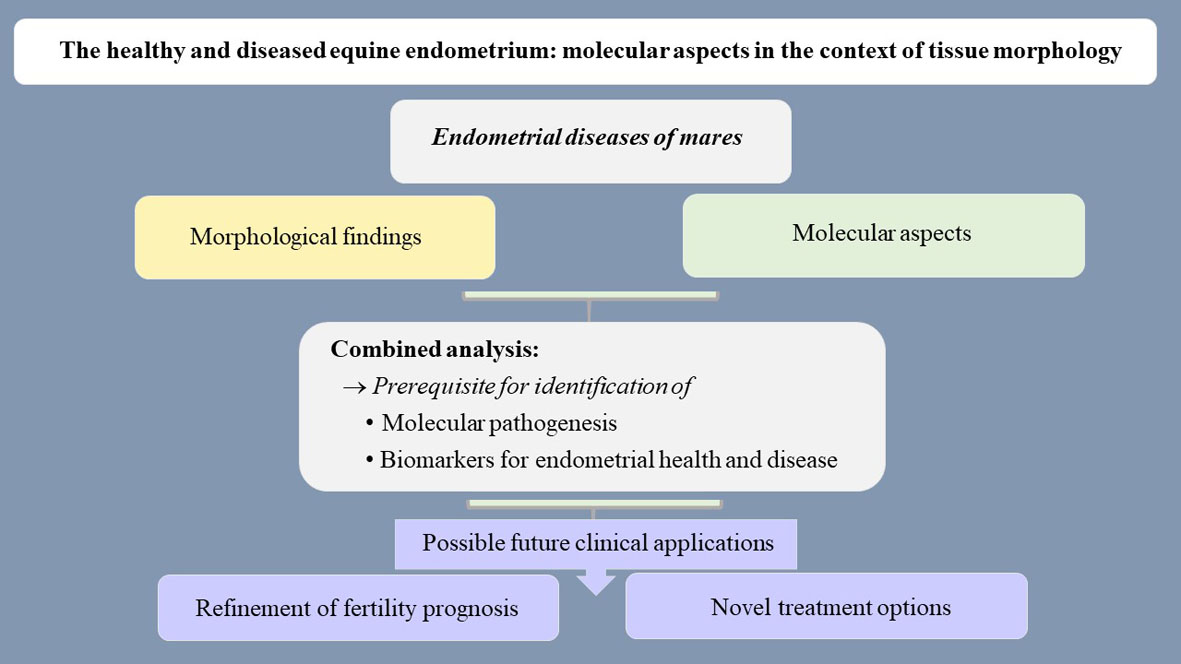

The content of this article is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Endometrial diseases are characterized by abnormal tissue morphology and associated molecular alterations. The combined analysis of both parameters provides insights into the molecular pathogenesis of endometrial diseases and assists in biomarker identification. These two aspects in turn will likely help to refine the fertility prognosis for an individual mare and to design novel treatment options.

References

- Kenney, R.M.; Doig, P.A.; Equine endometrial biopsy. In: Current therapy in theriogenology, 2nd; Morrow, D.A., Ed. WB SaundK.P. Freeman; J.F. Roszel; S.H. Slusher; M. Castro; Variation in glycogen and mucins in the equine uterus related to physiologic and pathologic conditions. Thers: Philadelphia, USA, 1986 ogenology 19986, pp., 723-729.0, 33, 799-808, 10.1016/0093-691x(90)90815-b.

- Schoon, H.-A.; Schoon, D.; Klug, E. Uterusbiopsien als Hilfsmittel für Diagnose und Prognose von Fertilitätsstörungen der Stute. Pferdeheilkunde 1992, 8, 355-362.

- Aurich, C.; Reproductive cycles of horses. AW. R. (Twink) Allen; Sandra Wilsher; Half a century of equine reproduction research and application: A veterinarytour de force. Equinimale Reproduction Science Veterinary Journal 2011, 124, 220-228, 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2011.02.005.7, 50, 10-21, 10.1111/evj.12762.

- Killisch, R.; Böttcher, D.; Theuß, T.; Edzards, H.; Martinsson, G.; Einspanier, A.; Gottschalk, J.; Schoon, H.-A. Seasonal or pathological findings? Morphofunctional characteristics of the equine endometrium during the autumn and spring transition. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2017, 52, 1011-1018.Killisch, R.; Böttcher, D.; Theuß, T.; Edzards, H.; Martinsson, G.; Einspanier, A.; Gottschalk, J.; Schoon, H.-A. Seasonal or pathological findings? Morphofunctional characteristics of the equine endometrium during the autumn and spring transition. Dom. Anim. 2017, 52, 1011-1018.

- Schoon, H.-A.; Schoon, D.; Klug, E. Die Endometriumbiopsie bei der Stute im klinisch-gynäkologischen Kontext. Pferdeheilkunde 1997, 13, 453-464.

- Grüninger, B.; Schoon, H.-A.; Schoon, D.; Menger, S.; Klug, E.; Incidence and morphology of endometrial angiopathies in mares in relationship to age and parity. B. Grüninger; H.-A. Schoon; D. Schoon; S. Menger; E. Klug; Incidence and morphology of endometrial angiopathies in mares in relationship to age and parity.. Journal of Comparative Pathology 1998, 119, 293-309, 10.1016/s0021-9975(98)80051-0.

- Buczkowska, J.; Kozdrowski, R.; Nowak, M.; Ra, A.; Mrowiec, J. Endometrosis - significance for horse reproduction, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and proposed therapeutic methods. Polish Journal of Veterinary Sciences 2014, 17, 547-554.Buczkowska, J.; Kozdrowski, R.; Nowak, M.; Ra, A.; Mrowiec, J. Endometrosis - significance for horse reproduction, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and proposed therapeutic methods. J. Vet. Sci. 2014, 17, 547-554.

- Katila, T.; Onset and duration of uterine inflammatory response of mares after insemination with fresh semen. Terttu Katila; Onset and Duration of Uterine Inflammatory Response of Mares after Insemination with Fresh Semen. Biology of Reproduction 1995, Mono 1, 515-517, , 52, 515-517, 10.1093/biolreprod/52.monograph_series1.515.

- Troedsson, M.H.T.; Uterine clearance and resistance to persistent endometritis in the mare. M.H.T. Troedsson; Uterine clearance and resistance to persistent endometritis in the mare. Theriogenology 1999, 52, 461-471, 10.1016/s0093-691x(99)00143-0.

- LeBlanc, M.M.; Causey R.C.; Clinical and subclinical endometritis in the mare: both threats to fertility. Michelle M. Leblanc; Rc Causey; Clinical and Subclinical Endometritis in the Mare: Both Threats to Fertility. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2009, 44, 10-22, 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2009.01485.x.

- Brunckhorst, D.; Schoon, H.-A.; Bader, H.; Sieme, H. Morphologische, enzyme- and immunhistologische Charakteristika des endometrialen Zyklus der Stute. Fertilität 1991, 7, 44-51.

- Ebert, A.; Schoon, D.; Schoon, H.-A. Age-related endometrial alterations in mares – biopsy findings of the last 20 years. In Leipziger Blaue Hefte, 7th Leipzig Veterinary Congress, 8th International Conference on Equine Reproductive Medicine; Rackwitz, R., Pees, M., Aschenbach, J.R., Gäbel, G., Eds.; Lehmanns Media GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 230–232.

- Schoon, H.-A.; Schoon, D. The category I mare (Kenney and Doig 1986): expected foaling rate 80-90% - fact or fiction? Pferdeheilkunde 2003, 19, 698-701.

- Schoon, H.-A.; Schoon, D.; Wiegandt, I.; Bartmann, C.-P.; Aupperle, H. “Endometrial maldifferentiation”- a clinically significant diagnosis in equine reproduction? Pferdeheilkunde 1999, 15, 555-559.

- Häfner, I.; Schoon, H.-A.; Schoon, D.; Aupperle, H. Glanduläre Differenzierungsstörungen im Endometrium der Stute – Lichtmikroskopische und immunhistologische Untersuchungen. Pferdeheilkunde 2001, 17, 103-110.

- Schoon, D.; Schoon, H.-A.; Klug, E. Angioses in the equine endometrium – pathogenesis and clinical correlations. Pferdeheilkunde 1999, 15, 541-546.

- Lehmann, J.; Ellenberger, C.; Hoffmann, C.; Bazer, F.W.; Klug, J.; Allen, W.R.; Sieme, H.; Schoon, H.-A.; Morpho-functional studies regarding the fertility prognosis of mares suffering from equine endometrosis. J. Lehmann; C. Ellenberger; C. Hoffmann; F.W. Bazer; J. Klug; W.R. Allen; H. Sieme; H.-A. Schoon; Morpho-functional studies regarding the fertility prognosis of mares suffering from equine endometrosis. Theriogenology 2011, 76, 1326-1336, 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.06.001.

- Kilgenstein, H.J.; Schöniger, S.; Schoon, D.; Schoon, H.-A. Microscopic examination of endometrial biopsies of retired sports mares: an explanation for the clinically observed subfertility? Research in Veterinary Science 2015, 99, 171-179, 10.1016/j.rvsc.2015.01.005Kilgenstein, H.J.; Schöniger, S.; Schoon, D.; Schoon, H.-A. Microscopic examination of endometrial biopsies of retired sports mares: an explanation for the clinically observed subfertility? Vet. Sci. 2015, 99, 171-179.

- Rudolph, N.; Schoon, H.-A.; Schöniger S. Immunohistochemical characterization of immune cells in fixed equine endometrial tissue: a diagnostic relevant method. Pferdeheilkunde - Equine Medicine 2017, 33, 524-537, 10.21836/PEM20170601.Rudolph, N.; Schoon, H.-A.; Schöniger S. Immunohistochemical characterization of immune cells in fixed equine endometrial tissue: a diagnostic relevant method. Pferdeheilkunde - Equine Medicine 2017, 33, 524-537.

- Mambelli, L.I.; Mattos, R.C.; Winter, G.H.Z.; Madeiro, D.S.; Morais, B.P.; Malschitzky, E.; Miglino, M.A.; Kerkis, A.; Kerkis, I.; Changes in expression pattern of selected endometrial proteins following mesenchymal stem cells infusion in mares with endometrosis. Lisley I. Mambelli; Rodrigo C. Mattos; Gustavo H. Z. Winter; Dener S. Madeiro; Bruna P. Morais; Eduardo Malschitzky; Maria Angélica Miglino; Alexandre Kerkis; Irina Kerkis; Changes in Expression Pattern of Selected Endometrial Proteins following Mesenchymal Stem Cells Infusion in Mares with Endometrosis. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e97889, 10.1371/journal.pone.0097889.

- Agnew, D.W.; MacLachlan, N.J.; Tumors of the genital system. In: Tumors in domestic animals, 5th ed.; Meuten, D.J., Editor. WiN. F. C. Gowing; Tumors of the Male Genital System. Journaley-B of Clackwell: Hoboken, New Jerseinical Pathology, USA 20 16, pp., 689-722.974, 27, 849-849, 10.1136/jcp.27.10.849-a.

- Aupperle, H.; Steiger, K.; Reischauer, A.; Schoon, H.-A. Ultrastructural and immunohistochemical characterization of the physiological and pathological inactivity of the equine endometrium. Pferdeheilkunde 2003, 19, 629-632.

- Aupperle, H.; Schoon, D.; Schoon, H.-A.; Physiological and pathological expression of intermediate filaments in the equine endometrium. Heike Aupperle; D Schoon; H.-A Schoon; Physiological and pathological expression of intermediate filaments in the equine endometrium. Research in Veterinary Science 2004, 76, 249-255, 10.1016/j.rvsc.2003.11.003.

- Hoffman, C.; Ellenberger, C.; Mattos, R.C.; Aupperle, H.; Dhein, S.; Stief, B.; Schoon, H.-A.; The equine endometrosis: New insights into the pathogenesis. Christine Hoffmann; Christin Ellenberger; Rodrigo Costa Mattos; Heike Aupperle; Stefan Dhein; Birgit Stief; Heinz-Adolf Schoon; The equine endometrosis: New insights into the pathogenesis. Animal Reproduction Science 2009, 111, 261-278, 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2008.03.019.

- Hoffmann, C., Bazer, F.W.; Klug, J.; Aupperle, H.; Ellenberger, C.; Schoon, H.-A.; Immunohistochemical and histochemical identification of proteins and carbohydrates in the equine endometrium. Christine Hoffmann; F.W. Bazer; J. Klug; H. Aupperle; C. Ellenberger; H.-A. Schoon; Immunohistochemical and histochemical identification of proteins and carbohydrates in the equine endometrium. Theriogenology 2009, 71, 264-274, 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2008.07.008.

- Schöniger, S.; Gräfe, H.; Schoon, H.-A.; Beta-defensin is a component of the endometrial immune defence in the mare. S Schöniger; H Gräfe; H-A Schoon; Beta-defensin is a component of the endometrial immune defence in the mare. Pferdeheilkunde - Equine Medicine 2013, 29, 335-346, 10.21836/PEM20130307., 335-346, 10.21836/pem20130307.

- Rebordão, M.R.; Galvão, A.; Szóstek, A.; Amaral, A.; Mateus, L.; Skarzynski, D.J.; Ferreira-Dias, G.; Physiopathologic mechanisms involved in mare endometrosis. Rebordão; António Galvão; Anna Szóstek-Mioduchowska; Ana Amaral; Luísa Mateus; Dariusz J. Skarzynski; Graça Maria Leitão Ferreira Dias; Physiopathologic Mechanisms Involved in Mare Endometrosis. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2014, 49 (S4), 82-87, , 82-87, 10.1111/rda.12397.

- Klose, K.; Schoon, H.-A. Periglandular inflammatory cells in the endometrium of the mare – A physiological defence mechanisms which impacts on the development of endometrosis. Pferdeheilkunde - Equine Medicine 2016, 32, 15-23. 10.21836/PEM20160102Klose, K.; Schoon, H.-A. Periglandular inflammatory cells in the endometrium of the mare – A physiological defence mechanisms which impacts on the development of endometrosis. Pferdeheilkunde 2016, 32, 15-23.

- Schöniger, S.; Böttcher, D.; Theuß, T.; Gräfe, H.; Schoon, H.-A.; New insights into the innate immune defences of the equine endometrium: in situ and in vitro expression pattern of beta-defensin. S Schöniger; D Böttcher; T. Theuß; H Gräfe; H-A Schoon; New insights into the innate immune defences of the equine endometrium: in situ and in vitro expression pattern of beta-defensin. Pferdeheilkunde - Equine Medicine 2016, 32, 4-14, 10.21836/PEM20160101., 4-14, 10.21836/pem20160101.

- Schöniger, S.; Gräfe, H.; Richter, F.; Schoon, H-A.; Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 as transcript and protein in the healthy and diseased equine endometrium. RH-A Schoon; D Schoon; The Category I mare (Kenney and Doig)- expected foaling rate 80-90% - fact or fiction?. Pfesrdearch in Veterinary Sciencheilkunde Equine Medicine 20018, 3, 118 , 278-287, 10.1016/j.rvsc.2018.03.001.9, 698-701, 10.21836/PEM20030626.

- Bischofberger, L.; Szewczyk, K.; Schoon, H.-A.; Unequal glandular differentiation of the equine endometrium – a separate endometrial alteration?. PfH A Schoon; A Schoon; [Iconography No. 11. Multiple heterotopic development of the testes in hermaphroditismus ambiglandularis].. DTW. Derdeutscheilkunde - Equine Medicine 20 tierarztliche Wochenschrift 19, 35 , 304–315, 10.21836/PEM20190401.81, 88, , null.

- Minkwitz, C.; Schoon, H.-A.; Zhang, Q.; Schöniger, S. Plasticity of endometrial epithelial and stromal cells – A new approach towards the pathogenesis of equine endometrosis. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2019, 54, 835-845, 10.1111/rda.13431.Minkwitz, C.; Schoon, H.-A.; Zhang, Q.; Schöniger, S. Plasticity of endometrial epithelial and stromal cells – A new approach towards the pathogenesis of equine endometrosis. Dom. Anim. 2019, 54, 835-845.

- Aupperle, H.; Özgen, S.; Schoon, H.-A.; Schoon, D.; Hoppen, H.O.; Sieme, H.; Tannapfel, A.; Cyclical endometrial steroid hormone receptor expression and proliferation intensity in the mare. H. Aupperle; H.-A. Schoon; H.-O. Hoppen; S. Özgen; H. Sieme; A. Tannapfel; Cyclical endometrial steroid hormone receptor expression and proliferation intensity in the mare. Equine Veterinary Journal 2010, 32, 228-232, 10.2746/042516400776563554.

- Schöniger, S.; Schoon, H.-A.; The healthy and diseased equine endometrium: a review of morphological features and molecular analyses.. Sandra Schöniger; Heinz-Adolf Schoon; The Healthy and Diseased Equine Endometrium: A Review of Morphological Features and Molecular Analyses. Animals (Basel) 2020, pii, E625, , 10, 625, 10.3390/ani10040625.

- Moore, E.; Kirwan, J.; Doherty, M.K.; Whitfield, P.D. Biomarker discovery in animal health and disease: the application of post-genomic technologies. Biomarker Insights 2007, 2,185–196.Moore,E.; Kirwan, J.; Doherty, M.K.; Whitfield, P.D. Biomarker discovery in animal health and disease: the application of post-genomic technologies. Biomarker Insights 2007, 2,185–196.

- Taylor, C.R.; Introduction to predictive biomarkers: definitions and characteristics. In: Predictive biomarkers in oncology, Badve, S., Kumar G.L., Eds. SpClive R. Taylor; Introduction to Predictive Biomarkers: Definitions and Characteristics. Predinger Nature: Cham, Switzerland ctive Biomarkers in Oncology 2019, pp., 3-18, 8, null, 3-18, 10.1007/978-3-319-95228-4_1.