Forest and Landscape Restoration (FLR) is considered worldwide as a powerful approach to recover ecological functionality and to improve human well-being in degraded and deforested landscapes.

- forest restoration

- human dimension of restoration

1. Introduction

Forest and Landscape Restoration (FLR) emerged in 2000 as a novel approach to regain ecological functionality and strengthen human well-being in deforested and degraded areas [1,2][1][2]. The FLR approach expanded from ecological restoration and from reflection upon failures in conservation and forest management approaches, and addresses interventions to recover or conserve native ecosystems. These interventions include farming and other initiatives to improve outcomes for local livelihoods, ecosystem services (ES), and biodiversity conservation at the landscape scale [3][3]. More recently, FLR has been included within the umbrella of “Nature-based Solutions”, and is aligned with other approaches to solve complex socio-environmental problems [4].

Forest and Landscape Restoration aims to better address the often-neglected human dimensions of restoration [5,6,7][5][6][7][8][9][10]. Although the human spectrum of restoration is important for stakeholder engagement, and thus for long-term restoration success [8][11], a systematic review of restoration monitoring found that 94% of the articles addressed the ecological aspects of restoration, while only 3.5% considered socio-economic ones [7][7]. The relatively few studies worldwide on the socio-economic aspects of restoration—when compared to those based on ecological aspects—focused on specific issues such as local community engagement, resource investments, job and income generation [5[5][7][12][13],7,9,10], or psychological outcomes (e.g., life satisfaction or the psychological benefits of restoration activities [11,12][14][15]).

Ideally, a broad set of human dimensions and socio-economic outcomes should be evaluated and integrated into restoration projects to ensure and assess achievements [8,13][11][16]. Such holistic overview is especially necessary for FLR because this approach recognizes the need to address the drivers of deforestation and land degradation. Moreover, FLR often depends on improving the long-term sustainability of production systems that may have negative short-term impacts on local livelihoods [14][17], especially where land tenure is insecure [15][18]. Without the active involvement of local people and other stakeholders, restoration may fail to fulfill the expected goals or lead to unintended negative consequences [8,16,17,18][11][8][9][19].

Evaluation of restoration initiatives focuses primarily on the ecological and biophysical outcomes of restoration [7][7]. More recently, a growing body of literature indicates the importance of human dimensions, such as socio-economic aspects and stakeholder engagement aspects for long-term restoration success [8,13,19][11][16][20]. The lack of appropriate consideration of key factors underlying restoration success may result, among other things, from the absence of a shared set of guiding principles and lack of interdisciplinary approaches. Despite several documents conceptualizing FLR and its principles [2[2][10],20], few systematic efforts have identified evidence-based principles of FLR activities that have been implemented on the ground [21,22,23][21][22][23]. A review of both the scientific and the practitioners’ literature (“grey literature”, such as case studies, reports and policy briefs) could assist the identification of existing concepts and practices associated with the ecological and human aspects of FLR, and ultimately offer critical guidance to the implementation of the >200 Mha of restoration commitments made to the Bonn Challenge and of the upcoming United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030).

Since FLR is a relatively recent restoration approach encompassing multiple human, ecological and economic dimensions, its principles and strategies are being constantly reviewed and refined [8[8][24][25][26],24,25,26], similarly to key underlying attributes of FLR such as gender equality [27], land tenure [18], funding [28][28], and definitions[1] [1]. There is a vast and still-growing literature of case studies of FLR projects that assess the implementation of principles, identify common challenges and make recommendations [13,18,21,26,29,30,31,32,33][13][18][22][26][29][30][31][32][33]. However, the holistic and complex principles of FLR defined in the literature are challenging to implement in practice [33][33]. Here, we assess the FLR principles and criteria in the literature published by practitioners and researchers. We conducted a systematic qualitative review to identify the main FLR concepts and definitions adopted in the academic and “practitioners” literature, and the underlying strategies commonly suggested to enable FLR implementation in different socio-ecological contexts. More specifically, we identified the main FLR principles in the literature, identified gaps, and provided recommendations based on existing established principles.

2. Overview of Recent Related Studies

2.1. Literature Characteristics

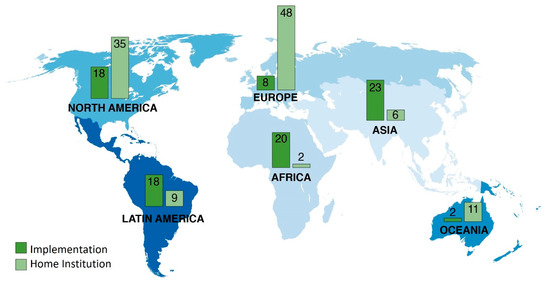

Except for a notable number of publications in 2005, the number of FLR publications steadily increased from 4 in 2010 to 21 in 2017, and more substantially since 2014 (Supplementary Material 5; summary of the WWF program in Mansourian and Vallauri [26][26]). While FLR implementation is widespread among countries in all continents (being the obvious exceptions Antarctica and Artic), most of the publications came from developed countries in North America, Oceania and Europe (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Forest and Landscape Restoration (FLR) sources surveyed by continent. “Implementation” refers to where FLR initiatives were established, while “Publication” refers to the country of the organization or of the first author of the source.

2.2. FLR Definitions and Aims

The terminology used in the published literature to describe FLR is diverse and has changed over time. Most sources (76.2%) refer to it as “Forest Landscape Restoration” although others adopt “Forest and Landscape Restoration” (16.6%) and “Forest Restoration in Landscapes” (1.4%). Sources adopting Forest and Landscape Restoration are more recent (2013–2017), denoting a change not only in terms of adoption, but also in concept, as the sector has broadened in scope beyond forestry and forest ecosystems. The most widely adopted FLR definition (38%), in both papers and documents, was proposed in 2000 by the WWF and IUCN (Table 1). It refers to FLR as “a process that aims to regain ecological integrity and enhance human well-being in deforested or degraded forest landscapes,”[34] [49] or minor variations in terms that do not generally affect its meaning, with a few exceptions, such as whether FLR is a planned process or not [50][35].

The concepts associated with the practical translations of FLR definitions during implementation vary in certain aspects, such as how the landscape is defined, how scale is incorporated (temporal and geographical), and how ecological dimensions are considered. Landscape definition varied across sources depending on disciplinary viewpoints [51,52][36][37]. However, authors agree the landscape is a heterogeneous mosaic of land uses, which may include old-growth and early successional forests, managed forests and non-forest lands, including agricultural and degraded lands [53,54][38][39]. Some authors emphasize the dynamism inherent to the landscape, classifying it as a human–environment interaction system [1,55][1][40].

Sources tended to agree on the importance of addressing geographical and temporal scales of FLR. At the geographical scale, the landscape was often generically defined as a continuous area, smaller than an ecoregion, but larger than a single site [56[41],57], which differs from its neighboring lands based on ecological and human aspects [56][42]. As for the temporal scale, authors concur that FLR is a long-term process [44,58],[43][44], which aims to achieve a range of improvements in the ecological and human aspects of the landscape, through restoring forest functions, generating ES, and managing trade-offs between competing objectives [59,60][45][46].

While this information was not included in our codebook, we observed that sources usually do not specify who defines the landscape spatial and temporal scale. Boedhihartono and Sayer[30] [30] describe FLR programs as a program of “seeking” solutions among stakeholders, rather than planning it top down. Including all stakeholders in the decision-making process from the early stages of FLR implementation contributes to project success and longevity, as indicated by recently published literature [8,13][11][16].

2.3. FLR and Associated Concepts

Here we list the main concepts associated to FLR found in the literature.

2.3.1. FLR Benefits and Contributions

Although often based on a priori aspirations instead of demonstrated empirical outcomes, the sources mentioned the following expected positive outcomes: (i) ecological, (ii) economic, and (iii) social. FLR was also mentioned as contributing to achieve several harmonized international restoration goals[47][48] [61,62] (Table 1).

2.3.2. FLR Planning and Implementation

Several sources reinforced the need to clarify FLR objectives in projects[49] [63], and to understand the ecological, socio-economic and political contexts and available technical options [49][63] to achieve the desired outcomes [25][25]. Planning FLR must encompass short-, medium- and long-term activities[37] [52]. Because restoration is a dynamic process, schedules need periodic revision [58]. The main FLR planning and implementation phases identified are listed below.

Defining a Landscape

Sources suggest that FLR implementation should begin by identifying the landscape unit, and a few published guidelines were provided on this. The systematic approach entitled “Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology” (ROAM), developed jointly by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the World Resources Institute (WRI), may contribute to assess the degradation types, and to identify priority areas and approaches for restoration in the landscape, but it does not provide specific guidelines to define the landscape unit [50][51][64,65]. Less systematized suggestions include the consideration of geographical and land-use characteristics through the use of maps, GIS, mathematical models, remote sensing inputs (e.g., aerial photos), and field data collection (e.g., ground-based observations)[52][53] [58,66,67].

Although systematic protocols may help, the reviewed studies emphasize the impracticality of defining a single landscape scale applicable to all FLR projects [1]. As the biological and human aspects need to be addressed case-by-case, the landscape scale will likely vary across FLR initiatives in different socio-ecological contexts[49] [63]. Yet, the lack of a clear technical approach to defining a landscape will result in a wide variation of landscape size and increases the challenges involved in comparing different initiatives and applying a single monitoring framework.

Choice of FLR Interventions

A suite of FLR interventions was described in the sources, including a wide range of options varying from assisting natural regeneration to commercial tree plantations and other interventions to reduce degradation (e.g., [26] and Table 1). The choice of FLR intervention, its spatial extent and location are derived from project goals and context-dependent ecological and human features of the landscape, such as previous land uses, proximity to forest remnants, human population density, and distribution of settlements [68,69][54][55]. Natural regeneration was considered by certain authors as the most desirable solution because of its benefits, scalability, and lower cost when compared with tree planting [2,58][2][52]. Among tree-planting practices, agroforestry was highlighted as the approach with the highest potential to generate human benefits. It allows expansion of tree cover while producing food [70] and generating other livelihood benefits, acting as a restoration “wild card”.

The choice of the restoration strategies was directly linked to the location and conditions where those strategies were implemented [54][55][68,69]. Dudley and Vallauri [56][71] emphasized the importance of identifying where forests are needed, since FLR does not aim to restore forests across the entire landscape due to other land-use claims or ecological constraints. Thus, interventions must prioritize usefulness regarding socio-economic, political, and ecological perspectives [56,63,71].

Regarding prioritization, Orsi[57] [72] presented guidelines for ranking sites in which forest restoration should be directed towards areas: (i) currently deforested, which were originally forest or woodland; (ii) with nearby existing forests; (iii) with large potential to conserve biodiversity, and (iv) sparsely human-populated. Locations with a mix of ownership and land tenure types were described as restoration challenges, when compared with landscapes dominated by few large properties. For example, Samsuri et al. [73][58] advocate that large/richer landowners may be less prone to participate on FLR initiatives in a watershed in Indonesia, while poorer people more commonly join restoration practices to increase their income levels. In areas densely populated and with major demands for food and forest products, the most suitable approach suggested is “mosaic restoration”, which is a land-sharing strategy that integrates trees with existing land uses, such as smallholder cropping and grazing, resulting in multifunctional landscapes [58][44].

2.3.3. Monitoring and Adaptive Management

Monitoring must be based on FLR objectives, and its quality and cost efficiency depends on devising a minimum set of essential indicators at site and landscape scales, and predicting—as much as possible—actions at different timescales [74][59]. Examples of socio-economic, ecological, financial and overall project aspects to monitor include those described in the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program in the United States [65,74][59]. Such activities can be carried out not only by natural and social scientists, but also by local communities or locally trained personnel engaged in participatory monitoring [75][60]. Given the myriad FLR activities, their dynamic contexts and the long timeframe to achieve many restoration outcomes, monitoring must be kept flexible to allow for adaptive management through learning by doing and improving practices over time [20,75,76][61][62].

2.3.4. Socioeconomic Outcomes

Concepts referring to socioeconomic outcomes of FLR encompasses humanl well-being and human and institutional capital.

Human Well-Being

Human well-being includes material and nonmaterial aspects, but the former is more often considered. Although seldom highlighted (Table 1), well-being improvements also come from nonmaterial benefits associated with FLR interventions, when landscape beauty, environmental quality, or recreational opportunities are enhanced[63][53] [44,67] or when physical health, for instance, is impacted by increasing water potability on reducing natural hazards [58][44].

Social and Human Capital

Project planning and implementation were commonly recommended to be participatory for four main reasons. First, including certain external partners (e.g., companies, private owners, research institutions, and NGOs) may allow technical improvement or addressing gaps in capacity or financing for implementing FLR [76,77][55][56]. For instance, partnerships with the public sector can be promoted by new legal frameworks that drive investments. Second, participation addresses the needs of local communities and less-influential stakeholders [45,63][64][65][66]. Thus, sources often argue for the importance of discussing stakeholders’ objectives and needs through workshops, meetings, and other activities that enable participation [78,79][57][58]. Third, participation is important whenever conflicts arise. For instance, Mansourian et al.[66] [63] highlight that economic value shifts in the landscape under restoration might generate conflicts, such as from the misuse of natural resources or exacerbating inequalities. The implementation of conflict-resolution strategies, such as hiring mediators or facilitators, is therefore recommended to avoid/mitigate such problems [79]. Fourth, the participation of communities in projects increases human and social capital through enhancing leadership and other capabilities, and develops their potential to influence policies and improve self-esteem [44,67,75][67][53][61].

The success of FLR projects also depends upon building local human capital, through more access to scientific information, technical assistance, and capacity-building to restoration interventions [80][59]. Inclusive processes should also go beyond sharing scientific and technical knowledge with local people, to incorporate their traditional knowledge on restoration strategies [60]. Certain authors argue that, to guarantee restoration success, forest agents should focus especially on small landowners and marginalized communities responsible for restoration implementation [44,81,82,83][60][61][62]. In addition to enhancing project success rates, education, training and capacity-building may increase job and income opportunities beyond the project itself.

Institutional Capital

Institutional capital (i.e., informal and formal rules, such as laws and policies) drives land-use decisions [44,70,82]. For effective compliance with legal instruments, organizations leading FLR implementation should assist local processes by promoting an adequate governance structure, strengthening the capacity of public institutions, engaging the private sector and markets, encouraging the equitable participation of stakeholders and, consequently, decentralizing decision-making to local groups [45].

2.3.5. Ecological Outcomes

Ecological outcomes encompasses the concepts directly related to biodiversity, ecological processes and ecosystem services.

Biodiversity Conservation

In highly fragmented and degraded landscapes, FLR can address a long-term solution for improving ecological functionality and agricultural productivity [75] by reducing pressure on natural forest remnants, augmenting their buffer zones and improving landscape connectivity [54,70,75,84][68]. Planting native species (e.g., in agroforestry, enrichment or mixed-species plantings) is recommended for ecosystem restoration and genetic diversity conservation [25,85,86]. The presence of seed sources (e.g., forest remnants and populations of targeted species) in the landscape ensures the availability of propagules for seedling production and to foment spontaneous regeneration in restoration sites through seed dispersal from remnants [85,86][69][70]. Supporting a network of seed collectors and high-quality seedling producers was also highlighted as a key aspect of restoration success [58,68].

Because not all species are able to colonize or persist in degraded or early successional forests, the protection of old-growth remnants was mentioned as crucial to conserve threatened species [85,86]. The control of superabundant and invasive species, protection against unwanted animals (e.g., uncontrolled grazing livestock and other ruminants), and enrichment of secondary forests [54,87] [71]are important complementary actions that preserve local ecological functions in mosaic landscapes.

Examples such as adopting some non-native species, especially in agroforestry systems and monoculture tree plantations, show remarkable potential to contribute to the overall goals of FLR programs, with benefits for carbon sequestration, soil protection, commercial production, and water infiltration [78,88][72]. However, sources argue for the crucial role of balancing where, when and which species to use to prevent the wholesale conversion of native forests to commercial plantations that may lead to a cryptic loss of carbon stocks, biodiversity, and ES [25].

Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

The global urgency and emerging interest to mitigate climate change, exemplified in recent ambitious global agreements, is highlighted as an opportunity for advancing FLR initiatives [25,75,85,89]. Forest and Landscape Restoration interventions may alleviate climate change effects on biodiversity and ES provision at the landscape, such as establishing protected areas for watershed and nature conservation, promoting forest restoration, establishing buffer zones [54][73], and controlling fires [65]. In this context, FLR could replace degraded lands with sustainable land use based on landscape-management practices [1,44,83].

Increase the Provision of Ecosystem Services

One motivation for restoring degraded lands is to improve the supply of goods and services from ecosystems other than climate change mitigation and adaptation [83][62]. At the landscape scale, balancing different ES to minimize trade-offs amongst them is key to FLR success [90][74]. Payment for Environmental Services (PES) is mentioned as a tool to foment large-scale restoration, together with law enforcement, securing political and public will, and providing financial support [44,54][73]. In certain cases, PES is based on cost-benefit analyses, which may be based on estimating individuals’ willingness to pay for restoration and its benefits, or land opportunity costs, for example. Chadourne et al. [53] [67] highlight that a limitation of “cost-benefit analysis” is that restoration returns may be underestimated by the community, since some “direct-use values” for forests (e.g., recreational use and aesthetic value), and the “non-use values” (e.g., enhanced biodiversity, the existence values of plant and animal species, values associated with a unique culture embodied by their natural heritage) are difficult to identify and incorporate into PES schemes.

2.3.6. Landscape Multifunctionality

Landscape multifunctionality refers to synergies and complementarities in a landscape with multiple land uses, each one valued differently by individual stakeholders [89][75]. Applying landscape multifunctionality concepts in FLR improves the coexistence of different land uses, accomplishing a range of stakeholders’ interests[76]。 [91]. Analogous to results from ES studies, landscape multifunctionality entails different spatial patterns, trade-offs and synergies [89][77].

The integrative effort to restore multiple functions on a landscape, by creating a “mosaic” where protected areas, forest types, management interests, and various land uses are combined and connected [92][78], is one of the major differences between site-centered ecological restoration and the landscape approach of FLR. Any FLR project will compose a set of site-based interventions whose combination and integration provides significant landscape-level outcomes [93][79]. Because of this landscape-scale integration, identifying degraded land cover through multi-stakeholder consultations and reviewing relevant land use/cover maps and statistics are essential [54,89,94][39][75][73].

3. Conclusions

FLR is a promising approach to generate multiple benefits and tackle some of the most pressing environmental challenges of the Anthropocene. Ecological principles are well-recognized within FLR programs, and despite the under-representation of human aspects in the scientific literature on restoration, these aspects were more often included in the “grey literature” of FLR initiatives. FLR has evolved to achieve integration of ecological and social objectives. Our results help to fulfill a knowledge gap in restoration science while also serving as a starting point for developing new tools, guidelines, frameworks, standards, and accountability schemes that could greatly improve FLR effectiveness, avoid unintended consequences, and increase transparency.

References

- Sabogal, C.; Besacier, C.; McGuire, D. Forest and landsacpe restoration: concepts, approaches and challenges for implementation. Unasylva. 2015, 66, 3–10, .

- Mansourian, S.; Vallauri, D.; Dudley, N. Forest restoration in landscapes: Beyond planting trees [Internet]. Forest Restoration in Landscapes: Beyond Planting Trees. WWF International, Avenue Mont Blanc, Gland 1196, Switzerland; 2005. 1–437 p.doi: 10.1007/0-387-29112-1.

- Gann, G.D.; Mcdonald, T.; Walder, B.; Aronson, J.; Nelson, C.R.; Hallett, J.G.; Eisenberg, C.; Guariguata, M.R.; Liu, J.; Echeverría, C.; et al. International principles and standards for the practice of ecological restoration. Society for Ecological Restoration; 2019. 100 p.

- IUCN. Nature Based Solutions [Internet]. Nature-Based Solutions. 2020.

- Aronson, J.; Blignaut, J.N.; Milton, S.J.; Le Maitre, D.; Esler, K.J.; Limouzin, A.; Fontaine, C.; de Wit, M.P.; Mugido, W.; Prinsloo, P.; et al. Are socioeconomic benefits of restoration adequately quantified? a meta-analysis of recent papers (2000-2008) in restoration ecology and 12 other scientific journals. Restor Ecol. 2010, 18, 143–54, doi: 10.1111/j.1526-100X.2009.00638.x.

- Uribe, D.; Geneletti, D.; del Castillo, R.F.; Orsi, F. Integrating stakeholder preferences and GIS-based multicriteria analysis to identify forest landscape restoration priorities. Sustain. 2014, 6, 935–51, doi: 10.3390/su6020935.

- Wortley, L.; Hero, J.M.; Howes, M. Evaluating ecological restoration success: A review of the literature. Restor Ecol. 2013, 21, 537–43, doi: 10.1111/rec.12028.

- Holl, K.D.; Brancalion, P.H.S. Tree planting is not a simple solution. Science (80- ). 2020, 368, 580–1, doi: 10.1126/science.aba8232.

- Viani, R.A.G.; Bracale, H.; Taffarello, D. Lessons learned from thewater producer project in the atlantic forest, Brazil. Forests. 2019, 10, 1–20, doi: 10.3390/f10111031.

- Mansourian, S.; Vallauri, D.; Dudley, N. Forest Restoration in Landscapes WWF ’ s Forests for Life Programme [Internet]. Forest Restoration in Landscapes. 2005. 1–440 p.

- Höhl, M.; Ahimbisibwe, V.; Stanturf, J.A.; Elsasser, P.; Kleine, M.; Bolte, A. Forest Landscape Restoration—What Generates Failure and Success? Forests. 2020, 11, 938, doi: 10.3390/f11090938.

- Brancalion, P.H.S.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Gandolfi, S.; Kageyama, P.Y.; Nave, A.G.; Gandara, F.B.; Barbosa, L.M.; Tabarelli, M. Instrumentos legais podem contribuir para a restauração de lorestas tropicais biodiversas. Rev Arvore. 2010, 34, 455–70, .

- Wu, T.; Kim, Y.-S.Y.S.; Hurteau, M.D. Investing in Natural Capital: Using Economic Incentives to Overcome Barriers to Forest Restoration. Restor Ecol. 2011, 19, 441–5, doi: 10.1111/j.1526-100X.2011.00788.x.

- Miles, I.; Sullivan, W.; Kuo, F. Ecological restoration volunteers: the benefits of participation. Urban Ecosyst. 1998, 2, 27–41, doi: 10.1023/A:1009501515335.

- Brancalion, P.H.S.S.; Cardozo, I.V.; Camatta, A.; Aronson, J.; Rodrigues, R.R. Cultural ecosystem services and popular perceptions of the benefits of an ecological restoration project in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Restor Ecol. 2014, 22, 65–71, doi: 10.1111/rec.12025.

- Parks, L. Challenging power from the bottom up? Community protocols, benefit-sharing, and the challenge of dominant discourses. Geoforum. 2018, 88, 87–95, doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.011.

- Chazdon, R.L.; Brancalion, P.H.S.S.; Lamb, D.; Laestadius, L.; Calmon, M.; Kumar, C. A Policy-Driven Knowledge Agenda for Global Forest and Landscape Restoration. Conserv Lett. 2017, 10, 125–32, doi: 10.1111/conl.12220.

- Bullock, J.M.; Aronson, J.; Newton, A.C.; Pywell, R.F.; Rey-Benayas, J.M. Restoration of ecosystem services and biodiversity: Conflicts and opportunities. Trends Ecol Evol. 2011, 26, 541–9, doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.06.011.

- McLain, R.; Lawry, S.; Guariguata, M.R.; Reed, J. Toward a tenure-responsive approach to forest landscape restoration: A proposed tenure diagnostic for assessing restoration opportunities. Land use policy. 2018, 103748, doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.053.

- Kremen, C.; Merenlender, A.M. Landscapes that work for biodiversity and people. Science (80- ). 2018, 362, doi: 10.1126/science.aau6020.

- Besseau, P.; Graham, S.S.; Christophersen, T. Restoring forests and landscapes: the key to a sustainable future. Vienna, Austria, Austria: Global Partnership on Forest and Landscape Restoration; 2018. 25 p.

- Newton, A.C.; del Castillo, R.F.; Echeverría, C.; Geneletti, D.; González-Espinosa, M.; Malizia, L.R.; Premoli, A.C.; Rey Benayas, J.M.; Smith-Ramírez, C.; Williams-Linera, G. Forest landscape restoration in the drylands of Latin America. Ecol Soc. 2012, 17, doi: 10.5751/ES-04572-170121.

- Ota, L.; Chazdon, R.L.; Herbohn, J.; Gregorio, N.; Mukul, S.A.; Wilson, S.J. Achieving Quality Forest and Landscape Restoration in the Tropics. Forests. 2020, 11, 820, doi: 10.3390/f11080820.

- Mansourian, S.; Parrotta, J. Forest Landscape Restoration: Integrated Approaches to Support Effective Implementation. Routledge; 2018. 266 p.

- Stanturf, J.A.; Kleine, M.; Mansourian, S.; Parrotta, J.; Madsen, P.; Kant, P.; Burns, J.; Bolte, A. Implementing forest landscape restoration under the Bonn Challenge: a systematic approach. Ann For Sci. 2019, 76, doi: 10.1007/s13595-019-0833-z.

- Brancalion, P.H.S.; Chazdon, R.L. Beyond hectares: four principles to guide reforestation in the context of tropical forest and landscape restoration. Restor Ecol. 2017, 25, 491–6, doi: 10.1111/rec.12519.

- Mansourian, S.; Vallauri, D. Restoring forest landscapes: Important lessons learnt. Environ Manage. 2014, 53, 241–51, doi: 10.1007/s00267-013-0213-7.

- IUCN. Gender-responsive restoration guidelines: A closer look at gender in the Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology. 2017, .

- Hennenmann, I. The Opportunities for External Business Investments in Landscape Restoration. 2013, .

- Beatty, C.; Raes, L.; Vogl, A.L.; Hawthorne, P.L.; Moraes, M.; Saborio, J.L.; Meza Prado, K. Landscapes, at your service: applications of the Restoration Opportunities Optimization Tool (ROOT) [Internet]. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature; 2018. 74 p.doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2018.17.en.

- Boedhihartono, A.K.; Sayer, J.A. Forest landsape retoration: restoring what and for whom? In: Stanturf JA, Lamb D, Madsen P, editors. Forest landscape restoration: integrating natural and social sciences. New York, USA: Springer; 2012. p. 309–23.

- Chazdon, R.L.; Gutierrez, V.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Laestadius, L.; Guariguata, M.R. Co-creating conceptual and working frameworks for implementing forest and landscape restoration based on core principles. Forests. 2020, 11, 1–24, doi: 10.3390/f11060706.

- Stanturf, J.A.; Mansourian, S.; Darabant, A.; Kleine, M.; Kant, P.; Burns, J.; Agena, A.; Batkhuu, O.N.; Ferreira, J.E.; Foli, E.; et al. Forest landscape restoration implementation: Lessons learned from selected landscapes. 2020.

- Ryan, G.W.; Bernard, H.R. Techniques to Identify Themes. Field methods. 2003, 15, 85–109, doi: 10.1177/1525822X02239569.

- WWF; IUCN. Forests Reborn: A workshop on forest restoration. 2000, 22, .

- Laestadius, L.; Buckingham, K.; Maginnis, S.; Saint-Laurent, C. Before Bonn and beyond: The history and future of forest landscape restoration. Unasylva. 2015, 66, 11–8, .

- van Oosten, C. Restoring Landscapes—Governing Place: A Learning Approach to Forest Landscape Restoration. J Sustain For. 2013, 32, 659–76, doi: 10.1080/10549811.2013.818551.

- Schlaepfer, R. Forest landscape restoration or forest restoration with a landscape approach? EFI News. 2005, 13, 7–9, .

- Ianni, E.; Geneletti, D. Applying the ecosystem approach to select priority areas for forest landscape restoration in the Yungas, northwestern Argentina. Environ Manage. 2010, 46, 748–60, doi: 10.1007/s00267-010-9553-8.

- Lamb, D.; Erskine, P.D.; Parrotta, J.A. Restoration of degraded tropical forest landscapes. Science (80- ). 2005, 310, 1628–32, doi: 10.1126/science.1111773.

- Dudley, N.; Dao, N.T. Case study: Monitoring forest landscape restoration in Vietnam. For Restor Landscapes Beyond Plant Trees. 2005, 157–8, doi: 10.1007/0-387-29112-1_22.

- Stanturf, J.A.; Palik, B.J.; Williams, M.I.; Dumroese, R.K.; Madsen, P. Forest Restoration Paradigms. J Sustain For. 2014, 33, S161–94, doi: 10.1080/10549811.2014.884004.

- Mansourian, S. In the eye of the beholder: Reconciling interpretations of forest landscape restoration. L Degrad Dev. 2018, 29, 2888–98, doi: 10.1002/ldr.3014

- Pfund, J.-L.; Stadtmüller, T. Brief historical review: from forest restoration to forest landscape restoration (FLR). InfoResources Focus. 2005, 2, 3–4, .

- Saint-Laurent, C. Optimizing Synergies on Forest Landscape Restoration Between the Rio Conventions and the UN Forum on Forests to Deliver Good Value for Implementers. Vol. 14, Review of European Community and International Environmental Law. 2005. p. 39–49doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9388.2005.00422.x.

- Hanson, C.; Buckingham, K.; Dewitt, S.; Laestadius, L. The Restoration Diagnostic. WRI; 2015. 96 p.doi: 978-1-56973-875-7.

- Mansourian, S.; Dudley, N. Challenges for forest landscape restoration based on WWF’s experience to date. In: Forest Restoration in Landscapes: Beyond Planting Trees. WWF International, 10 rte de Burtigny, 1268 Begnins, Switzerland; 2005. p. 94–8doi: 10.1007/0-387-29112-1_13.

- Barrow, E. 300,000 hectares restored in Shinyanga, Tanzania - But what did it really take to achieve this restoration? Sapiens. 2014, 7, 1–8, .

- Gourevitch, J.D.; Hawthorne, P.L.; Keeler, B.L.; Beatty, C.R.; Greve, M.; Verdone, M.A. Optimizing investments in national-scale forest landscape restoration in Uganda to maximize multiple benefits. Environ Res Lett. 2016, 11, 1–12, doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/11/11/114027.

- Angelieri, C.C.S.; Adams-Hosking, C.; Paschoaletto, K.M.; De Barros Ferraz, M.; De Souza, M.P.; McAlpine, C.A. Using species distribution models to predict potential landscape restoration effects on puma conservation. PLoS One. 2016, 11, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145232.

- Mansourian, S.; Stanturf, J.A.; Derkyi, M.A.A.; Engel, V.L. Forest Landscape Restoration: increasing the positive impacts of forest restoration or simply the area under tree cover? Restor Ecol. 2017, 1–6, doi: 10.1111/rec.12489.

- IUCN. Forest landscape restoration potential and impacts. Arbovitae. 2014, 45, 16, .

- Stanturf, J.; Mansourian, S.; Kleine, M. Implementing Forest Landscape Restoration: a practitioner ’ s guide. Vienna, Austria: International Union of Forest Research Organizations,; 2017. 128 p.doi: 10.13465/j.cnki.jvs.2016.19.021.

- Orsi, F.; Geneletti, D.; Newton, A.C. Towards a common set of criteria and indicators to identify forest restoration priorities: An expert panel-based approach. Ecol Indic. 2011, 11, 337–47, doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2010.06.001.

- Chadourne, M.H.; Cho, S.-H.S.H.; Roberts, R.K. Identifying Priority Areas for Forest Landscape Restoration to Protect Ridgelines and Hillsides: A Cost-Benefit Analysis. Can J Agric Econ. 2012, 60, 275–94, doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7976.2012.01252.x.

- FAO & Global Mechanism of the UNCCD. Sustainable financing for forest and landscape restoration: Opportunities, challenges and the way forward. Rome; 2015. 130 p.

- Chazdon, R.L.; Uriarte, M. The Role of Natural Regeneration in Large-scale Forest and Landscape Restoration: Challenge and Opportunity. Vol. 48, Biotropica. 2016. p. 709–15.

- FAO. Forest landscape restoration for Asia-Pacific forests. 2016. 198 p.

- Dudley, N.; Vallauri, D. Restoration of deadwood as a critical microhabitat in forest landscapes. In: Forest Restoration in Landscapes: Beyond Planting Trees. Equilibrium, 47 The Quays Cumberland Road, Bristol BS1 6UQ, United Kingdom; 2005. p. 203–7doi: 10.1007/0-387-29112-1_29.

- Orsi, F.; Church, R.L.; Geneletti, D. Restoring forest landscapes for biodiversity conservation and rural livelihoods: A spatial optimisation model. Environ Model Softw. 2011, 26, 1622–38, doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2011.07.008.

- Samsuri; Jaya, I.N.S.; Kusmana, C.; Murtilaksono, K. Restoration priority index development ofdegraded tropical forest landscape in batang toru watershed, North Sumatera, Indonesia. Biotropia (Bogor). 2014, 21, 111–24, doi: 10.11598/btb.2014.21.2.5.

- Schultz, C.A.; Coelho, D.L.; Beam, R.D. Design and governance of multiparty monitoring under the USDA Forest Service’s Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program. J For. 2014, 112, 198–206, doi: 10.5849/jof.13-070.

- van Bueren, E.L.; Blom, E. Hierarchical Framework for the Formulation of Sustainable Forest Management Standards [Internet]. The Tropenbos Foundation; 1996. 95 p.

- Adams, C.; Rodrigues, S.T.; Calmon, M.; Kumar, C. Impacts of large-scale forest restoration on socioeconomic status and local livelihoods: what we know and do not know. Biotropica. 2016, 48, 731–44, doi: 10.1111/btp.12385.

- Gourevitch, J.D.; Hawthorne, P.L.; Keeler, B.L.; Beatty, C.R.; Greve, M.; Verdone, M.A. Optimizing investments in national-scale forest landscape restoration in Uganda to maximize multiple benefits. Environ Res Lett. 2016, 11, 1–12, doi: 10.1088/1748-

- 9326/11/11/114027.

- Mansourian, S. In the eye of the beholder: Reconciling interpretations of forest landscape restoration. L Degrad Dev. 2018, 29, 2888–98, doi: 10.1002/ldr.3014.

- ITTO, I.T.T.O. Guidebook for the formulation of afforestation and reforestation projects under the clean development mechanism. ITTO, editor. Design. ITTO; 2006. 60 p.

- Dudley, N.; Aldrich, M. Five years of implementing forest landscape restoration. Lessons to date. WWF International; 2007. 24 p.

- Barr, C.M.; Sayer, J.A. The political economy of reforestation and forest restoration in Asia-Pacific: Critical issues for REDD+. Biol Conserv. 2012, 154, 9–19, doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.03.020.

- Souza, S.E.F.; Vidal, E.; Chagas, G. de F.; Elgar, A.T.; Brancalion, P.H.S. Ecological outcomes and livelihood benefits of community-managed agroforests and second growth forests in Southeast Brazil. Biotropica. 2016, 48, 868–81, doi: 10.1111/btp.12388.

- Urgenson, L.S.; Ryan, C.M.; Halpern, C.B.; Bakker, J.D.; Belote, R.T.; Franklin, J.F.; Haugo, R.D.; Nelson, C.R.; Waltz, A.E.M. Erratum to: Visions of Restoration in Fire-Adapted Forest Landscapes: Lessons from the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (Environmental Management, (2017), 59, 2, (338-353), 10.1007/s00267-016-0791-2). Environ Manage. 2017, 59, 354–5, doi: 10.1007/s00267-016-0814-z.

- Dudley, N. Policy interventions for forest landscape restoration. In: Forest Restoration in Landscapes: Beyond Planting Trees. Equilibrium, 47 The Quays Cumberland Road, Bristol BS1 6UQ, United Kingdom; 2005. p. 121–5doi: 10.1007/0-387-29112-1_17.

- Báez, S.; Ambrose EcoPar, K.; Hofstede Ecopar, E.R.; Sur, I. Ecological and social bases for the restoration of a High Andean cloud forest: preliminary results and lessons from a case study in northern Ecuador. Trop Mont Cloud For Sci Conserv Manag. 2011, 628–42, .

- Catterall, C.P. Roles of non-native species in large-scale regeneration of moist tropical forests on anthropogenic grassland. Biotropica. 2016, 48, 809–24, doi: 10.1111/btp.12384.

- Diederichsen, A.; Gatti, G.; Nunes, S.; Pinto, A. Diagnostic of key success factors for forest landscape restoration. Belém-PA, Brazil: Imazon; 2017. 83 p.

- Hampson, K.; Leclair, M.; Gebru, A.; Nakabugo, L.; Huggins, C. “There is No Program Without Farmers”: Interactive Radio for Forest Landscape Restoration in Mount Elgon Region, Uganda [Internet]. Society and Natural Resources. Farm Radio International, Arusha, Tanzania; 2016. p. 1–16doi: 10.1080/08941920.2016.1239148.

- Zhou, Y.F.; He, H.-S.; Bu, R.-C.; Jin, L.-R.; Li, X.-Z. Modeling of forest landscape change in Xiaoxinganling Mountains under different planting proportions of coniferous and broadleaved species. Chinese J Appl Ecol. 2008, 19, 1775–81, .

- Coello, J.; Cortina, J.; Valdecantos, A.; Varela, E. Forest landscape restoration experiences in southern Europe: Sustainable techniques for enhancing early tree performance. Unasylva. 2015, 66, 82–90, .