Trimethylornithine membrane lipids (TMOs) are a class of intact polar membrane lipids that were discovered in northern wetland Planctomycete species. The structure of TMOs is similar to ornithine lipids, but the terminal nitrogen of the ornithine amino acid head group is trimethylated, which gives the lipid a charged polar head group.

- trimethylornithine

- intact polar lipids

- cell membrane

- Planctomycetes

- northern wetlands

1. Introduction—Amino Acid Containing Membrane Lipids

Cell membranes are the interface between biological processes and the environment[1] [1]. Intact polar lipids (IPLs) are the constituent components of the cell membrane lipid bilayer, consisting of a polar head group and an apolar core. The diverse molecular structures of IPLs can provide functional and taxonomic information on the microbial community of a given environment[2][3] [2,3]. Following cell lysis, the head groups of IPLs are rapidly cleaved from the core lipids, on the order of days, thus making IPLs representative of living biomass[4][5] [4,5]. The structures of IPL head groups are very diverse, including common phosphoglycerol IPLs[6] [6] (e.g., phosphatidylcholine, PC; phosphatidylethanolamine, PE; etc.), and various bacterial IPLs that have polar head groups containing amino acids [7]. The amino acid IPLs phosphatidylserine and homoserine-containing betaine lipids have a glycerol backbone, while other amino acid containing lipids are glycerol free.

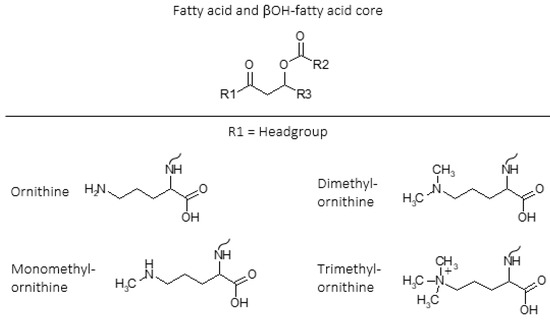

Ornithine lipids (OLs) are a common group of glycerol free amino acid containing lipids in bacteria (Figure 1). Approximately 50% of bacteria whose genomes have been sequenced are predicted to have the capability to synthesize OLs, but the genes necessary to form OLs are absent in archaea and eukaryotes[7][8][9][10] [7,8,9,10]. The OL head group consists of an amino acid that is linked by an amide bond to a β-hydroxy fatty acid, and the β-hydroxy fatty acid is “piggy back” esterified to a fatty acid (Figure 1). Additionally, lysine containing membrane lipids synthesized by Agrobacterium tumefaciens[11] [11] and Pedobacter saltans[12] [12] have the same ester linked fatty acid moiety and amide linked β-OH-fatty acid fatty acid structure that exists in OLs.

Figure 1. Intact polar lipid (IPL) structures of ornithine (OL), monomethylornithine (MMO), dimethylornithine (DMO), and trimethylornithine (TMO) lipids including fatty acid and βOH-fatty acid core lipids. R1 = headgroup; R2, R3 = alkane/alkene chains. Ornithine (OL;[13][14][15] [13,14,15]); monomethylornithine (MMO;[16] [16]); dimethylornithine (DMO;[16] [16]); trimethylornithine (TMO;[16] [16]). Figure adapted from[17] [17].

Ornithine lipids do not contain phosphorus (Figure 1), and can be produced by certain bacteria as an alternative to phosphoglycerol lipids in response to phosphorus limitation[18][19] [18,19]. Ornithine lipid head groups and the fatty acid groups can also be hydroxylated in response to different environmental stress conditions[20][21] [20,21]. It has been proposed that the hydroxylation of OLs increases hydrogen bonding between lipid molecules, thus providing enhanced membrane fluidity and stability[22] [22]. Similarly, it was discovered that lysine lipids (LLs) can be hydroxylated on both the head group and fatty acid chains in response to temperature and pH stress in the soil bacteria Pedobacter saltans[12] [12]. While various other microbial membrane lipids can be produced or modified in response to changing environmental conditions, OLs and other glycerol-free amino acid lipids are commonly observed to be involved in stress response[9] [9].

In 2013, three novel classes of amino acid containing membrane lipids were discovered in multiple Planctomycetes that were isolated from ombrotrophic (receives water only from rain) northern wetlands in European north Russia: mono-, di-, and trimethylated ornithine lipids ([16][16]; Figure 1). In particular, the unique physical properties of trimethylated ornithine lipids (TMOs) appear to be adapted to the acidic, low nutrient, and anoxic conditions of ombrotrophic northern wetlands.

2. Identification of TMOs in Diverse Environments

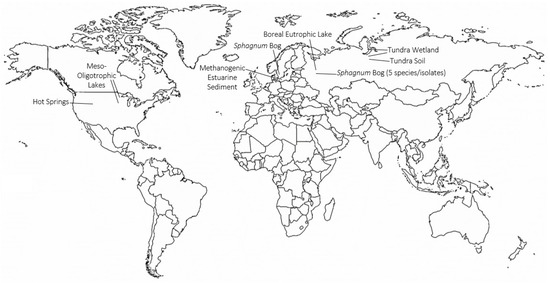

Continued work by the Svetlana Dedysh laboratory to characterize the microbial communities of northern latitude environments has led to the identification of TMOs in various recently described Planctomycete species (Figure 4). Trimethylornithines are the major membrane lipid constituents of the hydrolytic northern tundra wetland Planctomycete Paludisphaera borealis[23] [52], the psychrotolerant Isosphaeraceae Planctomycete from lichen-dominated tundra soils Tundrisphaera lichenicola[23] [53], the Sphagnum peat bog Planctomycete Fimbriiglobus ruber of the proposed family Gemmataceae[24] [54], the freshwater Planctomycete Limnoglobus roseus isolated from a boreal eutrophic lake[25] [55], and the psychrotolerant cellulolytic Gemmataceae Planctomycete from a littoral tundra wetland Frigoriglobus tundricola[26] [56]. The identification of TMOs in Planctomycetes from a northern wetland, tundra soil, peat bog, boreal eutrophic lake, and tundra wetland show that TMOs are more widespread in northern latitude environments than initially thought.

Figure 4. Global map showing locations and ecosystems where trimethylornithine lipids have been identified. Global map made with mapchart.net.

Trimethylornithine lipids have subsequently been identified in a wide range of aquatic environments since their discovery in Northern wetland Planctomycete isolates (Figure 4). An extensive study of trophic state impact on IPL distribution in North American lake surface waters from Minnesota and Iowa found the presence of TMOs, OLs, and betaine lipids in meso-oligotrophic lakes[27] [57]. The higher relative abundance of ornithines and TMOs in the observed meso-oligotrophic lakes was proposed to relate to a higher contribution of heterotrophic bacteria relative to phytoplankton in the lakes, similar to the presence of TMOs in abundant heterotrophic Planctomycetes of Northern peatlands. Trimethylornithines were identified in the oxic, micro-oxic, and anoxic layers of Northern wetland peat [49], therefore, it is consistent to observe TMOs in oxic lake waters. Conversely, TMOs were later identified in enrichment cultures of anoxic methanogenic sediment from Arhus Bay, Denmark[28] [58], akin to the presence of TMOs in anoxic methanogenic peat. Among the enrichment cultures that contained TMOs, the cultures that received sulfate amendments had higher TMO relative abundances than the TMO-containing enrichment culture that did not receive additional sulfate.

Trimethylornithine lipids were also recently observed in microbial communities of multiple Yellowstone National Park hot springs [29][30]([59,60]; Figure 4). The fatty acids of some of the hot spring TMOs were hydroxylated[30] [59]. Ornithine lipids were also observed in the hot springs, and various OLs were found to contain hydroxylated fatty acids as well. It has previously been shown that OL and LL fatty acids can be hydroxylated in response to temperature and pH stress [12][20][21][12,20,21]. The hydroxylated fatty acids of Yellowstone TMOs and OLs may also be a stress response to elevated hot spring temperatures in order to create more hydrogen bonding and membrane stability. The high relative abundance of TMOs in the Yellowstone hot spring microbial undermat suggests that these lipids could originate from abundant anoxygenic phototrophic organisms in these layers; however, the authors suggest a chemoheterotrophic origin[31] [60], which aligns much closer with the known metabolic niches of TMO producing microbes. Given that TMOs have only been identified in Planctomycete species, further work characterizing new microbial species in environments where TMOs are observed will help confirm if these lipids are lipid biomarkers for Planctomycetes, or if they are a more taxonomically diverse membrane lipid.

3. TMOs: Specialized Lipids with Potential Broad Distribution

The distribution of TMOs among different types of ecosystems suggests that this class of lipids may have specialized and flexible functions depending on the surrounding environmental conditions or microbial community. The similar structure of the trimethylated terminal nitrogen of TMOs compared to the choline moiety of PCs, without the presence of phosphorus, suggests that TMOs may have a similar membrane structural role to PCs under phosphorus limiting conditions[16] [16]. The increase of relative TMO production in Planctomycete cultures grown under low oxygen conditions [49] and the presence of hydroxylated TMOs in hot spring environments[30] [59] further link TMOs to stress response, similar to the production and modification of other amino acid containing lipids under the nutrient, temperature, or pH stress conditions described above. Additionally, hot spring TMOs are present in high relative abundance at and below the oxic–anoxic interface of the microbial mat, and not present in the oxic upper layer[31] [60]. The increased relative production of TMO lipids in low oxygen cultures, the presence of abundant TMOs in anoxic methanogenic peat, anoxic hot spring microbial mats, and anoxic methanogenic estuarine sediment enrichment cultures further indicate that these lipids may be present in other anoxic and/or methanogenic environments.

In addition to links between TMOs and stress responses, TMOs have been observed in both oxic and anoxic heterotrophic microbial communities in northern peatlands, northern lakes, tundra soils, tundra wetlands, northern eutrophic lakes, and mid-latitude meso-oligotrophic lakes (Figure 4). Future microbial lipidomics studies on aquatic and soil ecosystems at northern and mid-latitudes should include TMOs in their IPL targets to further characterize the microbial community and potential contribution of Planctomycetes in their study systems. Such studies in aquatic and soil ecosystems at lower latitudes will be intriguing for potentially identifying TMOs as well, thus expanding the known geographic distribution of these lipids. Similar to high latitude peatlands, tropical peatlands are important global carbon stores, with variable carbon fluxes in relation to land use and climate change[32][33] [61,62]. Planctomycetes have been identified in metabolically diverse tropical peat microbial communities[34] [63], suggesting that TMOs could be important microbial membrane constituents in these environments. Coastal salt marshes also contain diverse microbial communities, including Planctomycetes[35] [64], that are involved in the decomposition of recalcitrant organic matter[36][37] [65,66], that commonly include anoxic and methanogenic sediment zones at depth[38] [67]. The distribution of TMOs and potential modifications of TMOs could inform the role of Planctomycetes and adaptations to lower latitude environments, such as tropical peatlands and coastal salt marshes.

A new area of application for the analysis of TMOs and other IPLs is forensics microbiome research[39][40] [68,69]. Understanding heterotrophic microbial communities is crucial in forensics studies that investigate changing microbiomes of decaying vertebrate remains. Bacterial community succession analysis of the necrobiome associated with decaying vertebrate remains has revealed a negative relationship for overall taxon richness with increasing decomposition[41] [70], and heterotrophic bacteria have also been observed to increase during decomposition of vertebrate remains[42] [71]. Microbial community succession in forest soil below decomposing human cadavers has shown that Planctomycete sequence abundance decreased during the bloat-active decomposition stage to the advanced decay II stage, but then returned to original relative abundance during the advanced decay III stage[43] [72]. This suggests that the presence of soil Planctomycetes under decayed vertebrate remains could indicate that the advanced decomposition of labile organic matter has taken place allowing Planctomycetes cell numbers to recover. This in agreement with the role of soil Planctomycetes to be involved in the degradation of recalcitrant material after labile material has been consumed[44] [37]. In such a scenario, TMOs and other microbial IPLs could be used to track microbiome changes during carrion decay. Further microbiome and environmental lipidomics research involving TMOs in diverse ecosystems will help reveal the evolution, functions, and applications of these unique membrane lipids.