Dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy (DDC) is currently the leading cause of death in patients with dystrophinopathies. Targeting myocardial fibrosis (MF) has become a major therapeutic goal in order to prevent the occurrence of DDC.

- dystrohinopathy

- duchenne muscular disease

1. Introduction

Dystrophinopathies are heterogeneous X-linked recessive disorders with a common genetic origin, mutations in the dystrophin gene (DMD OMIM300377; chromosome Xp21.1.) that lead to the complete loss or deficient synthesis of the dystrophin protein. Dystrophinopathies include a broad genetic and phenotypic spectrum, mainly Duchenne muscular disease (DMD), the most common and severe form, and Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) [1,2][1][2]. The varying degree of dystrophin expression explains the different clinical courses of these diseases: while DMD results from a complete loss of dystrophin, BMD is due to the expression of a truncated but partially functional protein. The absence of dystrophin protein in the heart results in these patients invariably developing dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy (DDC), mainly in the form of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with congestive heart failure (CHF) and rhythm disturbances [3].

2. Overview of the Mouse Models Used for the Study of DDC

Most of the evidence summarized below comes from investigations with the

mdx(X-chromosome-linked muscular dystrophy) and

dko(

dystrophin–utrophindouble knockout) mice, which represent the most widely used models to investigate the pathogenesis of DDC. The

mdxmouse carried a nonsense mutation in exon 23 of the mouse dystrophin gene (located on the mouse X chromosome), resulting in an early termination codon and a truncated dystrophin protein. The mdx model lacks functional dystrophin and is the rodent analogue to the

DMDmutation in humans regarding genotype, molecular mechanisms and histology, but with a mild

DMDphenotype. Notably, cardiac functional defects are not apparent in young adult

mdxmice and the lifespan is not significantly reduced. Utrophin is a dystrophin homologous protein with the same sarcolemmal distribution in murine cardiomyocyte. Utrophin is upregulated in mdx heart compensating the loss of dystrophin and explaining its mild cardiac phenotype regarding humans. Therefore, both utrophin and dystrophin loss results in a more severe phenotype in

dkothan the

mdxmouse. Although the cardiac phenotype of

DMDmore closely resembles that of

dkothan of

mdxmice, the cardiomyopathy occurrence is seen inconsistently, and it is unlikely to be the cause of death for all animals.

3. Overview of the Fibrotic Process in DDC

The development of MF is the cornerstone pathophysiological mechanism in DDC. The development of new imaging techniques such as cardiac MRI with LGE has led to an increased identification of the presence of MF in children, a population where myocardial biopsies are not usually performed [39,40][4][5]. Noteworthy, cardiac MRI is usually performed at the age when sedation is not necessary and LGE technique requires a minimum threshold volume of myocardial fibrosis before becoming evident on CMR. Consequently, this can lead to a delayed identification or underestimation of MF. The detection of early subclinical cardiovascular manifestations long before the identification of MF on cardiac MRI points out that MF could be present already at early stages of the disease [41][6], and this period would be a large window of opportunity for interventions aimed at preventing MF occurrence [31,32,42][7][8][9]. The understanding of the pathophysiologic processes leading to the development of MF in DDC is crucial for this purpose. During the last 20 years a growing knowledge has been obtained from parallel investigation in animal models and humans suggesting that RAAS is a pivotal pathway in the regulation of MF in DDC. RAAS blockade has become the hallmark of cardioprotective interventions to ameliorate the adverse myocardial remodelling and progression of heart failure that follows cardiomyocyte necrosis in dystrophinopathies [43][10]. Indeed, current guidelines recommend that children with DMD should start on RAAS inhibition (including AT1R blockers (ARBs), and ACEI) by age 10 or earlier if myocardial dysfunction is detected [44][11].

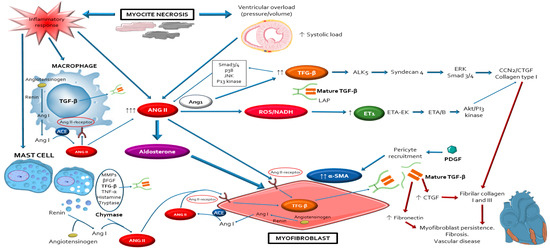

After the occurrence of cardiac injury and cardiomyocyte death secondary to absent or defective dystrophin protein, the inflammatory/immune cells (lymphocytes, macrophages, mast cells) infiltrate the wounded myocardium to clear dead tissue and release pro-fibrotic cytokines. This led to differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, the major effectors for the pathological MF and remodelling observed in DDC [45,46,47,48,49][12][13][14][15][16]. The repetitive chronic injurious stimuli that occur in dystrophinopathies may cause perpetual activation of myofibroblasts leading to excessive deposits of extracellular matrix (ECM) materials, progressive fibrosis and maladaptive cardiac remodelling. Major characteristics of muscle biopsies of the dystrophic hearts include necrotic muscle fibres surrounded by macrophages, lymphocytes, mast cells and myofibroblasts [31[7][9][17][18],42,50,51], supporting that DDC results from imbalance between muscle fibre necrosis, inflammatory response and myofibroblasts regeneration [30,52,53,54,55,56,57,58][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26]. At the molecular level, the fibrotic process is regulated by a complex network of signalling pathways that includes inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, macrophages, mast cells), inflammatory factors (IL, TNF-a, NF-kB) peptides (ANG2, endothelin 1 (ET-1), aldosterone), growth factors (Transforming growth factor (TGF-β), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)), ions (Ca2+), oxidative stress molecules (NADPH, NOX, LOX…), adhesion molecules (integrins, osteopontin), matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), and immunoproteasome (Figure 21) [59,60,61,62,63,64,65][27][28][29][30][31][32][33]. These interdependent factors favour the activation and proliferation of myofibroblasts [66,67,68][34][35][36]. The increased mechanical tension of the myocardium due to the changes in ECM stiffness also acts as alternative regulator of myofibroblasts differentiation. The histopathologic findings of a greater degree of fibrotic changes in basal cardiac region than the apical region of dystrophic hearts, reinforce that mechanical forces influences in the development of MF in DDC [45,47,69,70,71,72,73,74,75][12][14][37][38][39][40][41][42][43].

Schematic representation of the complex network of interplayed cellular and molecular mechanisms that participle in the development of myocardial fibrosis leading to the occurrence of dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy. Notice that angiotensin 2 with its type 1 receptor, have a central role modulating the activation of most of these pathways through its autocrine/paracrine actions, mostly via the TFG-β pathway. AngioTable 2. is also essential in order to maintain and perpetuate the profibrotic response, providing a source for a positive auto-feedback. Abbreviations: ACE: angiotensin-converting-enzyme; Akt: protein kinase B; ALK5: activin receptor-like kinase-1; Ang I: angiotensin I; ANG II: angiotensin II; CCN2/CTGF: connective tissue growth factor; ET1: endothelin-1; ETA: endothelin receptor A; JNK: Jun N-Terminal Kinase; LAP: latency-associated peptides; MMPs: matrix metalloproteinases; NADH: reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; PDGF: platelet derived growth factor; PI3: phosphoinositide 3; ROS: reactive oxygen species; Smad3/4: mothers against decapentaplegic homolog ¾; TFG-β: transforming growth factor-beta; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor alpha; α-SMA: alpha-smooth muscle actin; βFGF: basic fibroblast growth factor the severity of DDC at older ages and ANG2/AT1R blockade reduces oxidative stress and fibrosis and improved improves autonomic function and cardiac functionality in dystrophic mice [44][45][46].

All the mentioned above mechanisms involved in MF in DDC are similar to those occurring in more studied models, such as myocardial infarct or hypertension, where the RAAS has been extensively shown to modulate the actions of most of the remaining pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory factors mentioned above, mainly through its primary effector molecule ANG2 and the ANG2 type 1 receptor (AT1R) [76,77,78,79,80,81][47][48][49][50][51][52].

References

- Brandsema, J.F.; Darras, B.T. Dystrophinopathies. Semin. Neurol. 2015, 35, 369–384.

- Morales, J.A.; Mahajan, K. Dystrophinopathies. In Gene Reviews; Stat Pearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020.

- Kamdar, F.; Garry, D.J. Dystrophin-Deficient Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 2533–2546.

- Power, L.C.; O’Grady, G.L.; Hornung, T.S.; Jefferies, C.; Gusso, S.; Hofman, P.L. Imaging the heart to detect cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A review. Neuromuscul. Disord. Nmd 2018, 28, 717–730.

- D’Amario, D.; Amodeo, A.; Adorisio, R.; Tiziano, F.D.; Leone, A.M.; Perri, G.; Bruno, P.; Massetti, M.; Ferlini, A.; Pane, M.; et al. A current approach to heart failure in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Heart 2017, 103, 1770–1779.

- Mavrogeni, S.I.; Markousis-Mavrogenis, G.; Papavasiliou, A.; Papadopoulos, G.; Kolovou, G. Cardiac Involvement in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Related Dystrophinopathies. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1687, 31–42.

- Finsterer, J.; Stollberger, C. The heart in human dystrophinopathies. Cardiology 2003, 99, 1–19.

- Tandon, A.; Villa, C.R.; Hor, K.N.; Jefferies, J.L.; Gao, Z.; Towbin, J.A.; Wong, B.L.; Mazur, W.; Fleck, R.J.; Sticka, J.J.; et al. Myocardial fibrosis burden predicts left ventricular ejection fraction and is associated with age and steroid treatment duration in duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e001338.

- Nigro, G.; Comi, L.I.; Politano, L.; Bain, R.J. The incidence and evolution of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Int. J. Cardiol. 1990, 26, 271–277.

- McNally, E.M.; Kaltman, J.R.; Benson, D.W.; Canter, C.E.; Cripe, L.H.; Duan, D.; Finder, J.D.; Groh, W.J.; Hoffman, E.P.; Judge, D.P.; et al. Contemporary cardiac issues in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy. Circulation 2015, 131, 1590–1598.

- Birnkrant, D.J.; Bushby, K.; Bann, C.M.; Alman, B.A.; Apkon, S.D.; Blackwell, A.; Case, L.E.; Cripe, L.; Hadjiyannakis, S.; Olson, A.K.; et al. Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2, respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 347–361.

- Shimizu, I.; Minamino, T. Physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016, 97, 245–262.

- Haudek, S.B.; Cheng, J.; Du, J.; Wang, Y.; Hermosillo-Rodriguez, J.; Trial, J.; Taffet, G.E.; Entman, M.L. Monocytic fibroblast precursors mediate fibrosis in angiotensin-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 49, 499–507.

- Leask, A. Getting to the heart of the matter: New insights into cardiac fibrosis. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1269–1276.

- Crowley, S.D.; Coffman, T.M. Recent advances involving the renin-angiotensin system. Exp. Cell Res. 2012, 318, 1049–1056.

- Weber, K.T.; Sun, Y.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Ahokas, R.A.; Gerling, I.C. Myofibroblast-mediated mechanisms of pathological remodelling of the heart. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 15–26.

- Nishimura, T.; Yanagisawa, A.; Sakata, H.; Sakata, K.; Shimoyama, K.; Ishihara, T.; Yoshino, H.; Ishikawa, K. Thallium-201 single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in patients with duchenne’s progressive muscular dystrophy: A histopathologic correlation study. Jpn. Circ. J. 2001, 65, 99–105.

- Sanyal, S.K.; Johnson, W.W.; Thapar, M.K.; Pitner, S.E. An ultrastructural basis for electrocardiographic alterations associated with Duchenne’s progressive muscular dystrophy. Circulation 1978, 57, 1122–1129.

- Quinlan, J.G.; Hahn, H.S.; Wong, B.L.; Lorenz, J.N.; Wenisch, A.S.; Levin, L.S. Evolution of the mdx mouse cardiomyopathy: Physiological and morphological findings. Neuromuscul. Disord. NMD 2004, 14, 491–496.

- Kamogawa, Y.; Biro, S.; Maeda, M.; Setoguchi, M.; Hirakawa, T.; Yoshida, H.; Tei, C. Dystrophin-deficient myocardium is vulnerable to pressure overload in vivo. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001, 50, 509–515.

- Lefaucheur, J.P.; Sebille, A. Basic fibroblast growth factor promotes in vivo muscle regeneration in murine muscular dystrophy. Neurosci. Lett. 1995, 202, 121–124.

- Spurney, C.F.; Sali, A.; Guerron, A.D.; Iantorno, M.; Yu, Q.; Gordish-Dressman, H.; Rayavarapu, S.; Van Der Meulen, J.; Hoffman, E.P.; Nagaraju, K. Losartan decreases cardiac muscle fibrosis and improves cardiac function in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 16, 87–95.

- Nakamura, A.; Yoshida, K.; Takeda, S.; Dohi, N.; Ikeda, S.-I. Progression of dystrophic features and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and calcineurin by physical exercise, in hearts of mdx mice. FEBS Lett. 2002, 520, 18–24.

- Cohn, R.D.; Durbeej, M.; Moore, S.A.; Coral-Vazquez, R.; Prouty, S.; Campbell, K.P. Prevention of cardiomyopathy in mouse models lacking the smooth muscle sarcoglycan-sarcospan complex. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, R1–R7.

- Marques, M.J.; Barbin, I.C.; Taniguti, A.P.; Oggian, D.S.; Ferretti, R.; Santo Neto, H. Myocardial fibrosis is unaltered by long-term administration of L-arginine in dystrophin deficient mdx mice: A histomorphometric analysis. Acta Biol. Hung. 2010, 61, 168–174.

- Fan, D.; Takawale, A.; Lee, J.; Kassiri, Z. Cardiac fibroblasts, fibrosis and extracellular matrix remodeling in heart disease. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2012, 5, 15.

- Stempien-Otero, A.; Kim, D.H.; Davis, J. Molecular networks underlying myofibroblast fate and fibrosis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016, 97, 153–161.

- Liu, F.; Liang, Z.; Xu, J.; Li, W.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, C. Activation of the wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling Pathway in Polymyositis, Dermatomyositis and Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J. Clin. Neurol. 2016, 12, 351–360.

- Davis, J.; Molkentin, J.D. Myofibroblasts: Trust your heart and let fate decide. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 70, 9–18.

- Duerrschmid, C.; Trial, J.; Wang, Y.; Entman, M.L.; Haudek, S.B. Tumor necrosis factor: A mechanistic link between angiotensin-II-induced cardiac inflammation and fibrosis. Circ. Heart Fail. 2015, 8, 352–361.

- Takawale, A.; Zhang, P.; Patel, V.B.; Wang, X.; Oudit, G.; Kassiri, Z. Tissue Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 Promotes Myocardial Fibrosis by Mediating CD63-Integrin beta1 Interaction. Hypertension 2017, 69, 1092–1103.

- Ma, F.; Li, Y.; Jia, L.; Han, Y.; Cheng, J.; Li, H.; Qi, Y.; Du, J. Macrophage-stimulated cardiac fibroblast production of IL-6 is essential for TGF beta/Smad activation and cardiac fibrosis induced by angiotensin II. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35144.

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.X.; Li, Y.L.; Zhang, C.C.; Zhou, C.Y.; Wang, L.; Xia, Y.L.; Du, J.; Li, H.H. MicroRNA Let-7i negatively regulates cardiac inflammation and fibrosis. Hypertension 2015, 66, 776–785.

- Chen, C.; Du, J.; Feng, W.; Song, Y.; Lu, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y. beta-Adrenergic receptors stimulate interleukin-6 production through Epac-dependent activation of PKCdelta/p38 MAPK signalling in neonatal mouse cardiac fibroblasts. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 166, 676–688.

- Liu, N.; Xing, R.; Yang, C.; Tian, A.; Lv, Z.; Sun, N.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z. HIP-55/DBNL-dependent regulation of adrenergic receptor mediates the ERK1/2 proliferative pathway. Mol. Biosyst. 2014, 10, 1932–1939.

- Fu, X.; Khalil, H.; Kanisicak, O.; Boyer, J.G.; Vagnozzi, R.J.; Maliken, B.D.; Sargent, M.A.; Prasad, V.; Valiente-Alandi, I.; Blaxall, B.C.; et al. Specialized fibroblast differentiated states underlie scar formation in the infarcted mouse heart. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2127–2143.

- Schroer, A.K.; Merryman, W.D. Mechanobiology of myofibroblast adhesion in fibrotic cardiac disease. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 1865–1875.

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Hecker, L.; Kurundkar, D.; Kurundkar, A.; Liu, H.; Jin, T.H.; Desai, L.; Bernard, K.; Thannickal, V.J. Inhibition of mechanosensitive signaling in myofibroblasts ameliorates experimental pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 1096–1108.

- Kural, M.H.; Billiar, K.L. Myofibroblast persistence with real-time changes in boundary stiffness. Acta Biomater. 2016, 32, 223–230.

- Li, L.; Fan, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.Y.; Cui, X.B.; Wu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, L.L. Angiotensin II increases periostin expression via Ras/p38 MAPK/CREB and ERK1/2/TGF-beta1 pathways in cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 91, 80–89.

- Wu, H.; Chen, L.; Xie, J.; Li, R.; Li, G.N.; Chen, Q.H.; Zhang, X.L.; Kang, L.N.; Xu, B. Periostin expression induced by oxidative stress contributes to myocardial fibrosis in a rat model of high salt-induced hypertension. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 776–782.

- Kawano, H.; Cody, R.J.; Graf, K.; Goetze, S.; Kawano, Y.; Schnee, J.; Law, R.E.; Hsueh, W.A. Angiotensin II enhances integrin and alpha-actinin expression in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 2000, 35, 273–279.

- Megeney, L.A.; Kablar, B.; Perry, R.L.; Ying, C.; May, L.; Rudnicki, M.A. Severe cardiomyopathy in mice lacking dystrophin and MyoD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 220–225.

- Sabharwal, R.; Chapleau, M.W. Autonomic, locomotor and cardiac abnormalities in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy: Targeting the renin-angiotensin system. Exp. Physiol. 2014, 99, 627–631.

- Sabharwal, R.; Weiss, R.M.; Zimmerman, K.; Domenig, O.; Cicha, M.Z.; Chapleau, M.W. Angiotensin-dependent autonomic dysregulation precedes dilated cardiomyopathy in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Exp. Physiol. 2015, 100, 776–795.

- Sabharwal, R.; Cicha, M.Z.; Sinisterra, R.D.; De Sousa, F.B.; Santos, R.A.; Chapleau, M.W. Chronic oral administration of Ang-(1-7) improves skeletal muscle, autonomic and locomotor phenotypes in muscular dystrophy. Clin. Sci. 2014, 127, 101–109.

- Santos, R.A.; Ferreira, A.J.; Simoes, E.S.A.C. Recent advances in the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-angiotensin(1-7)-Mas axis. Exp. Physiol. 2008, 93, 519–527.

- Sun, G.; Haginoya, K.; Dai, H.; Chiba, Y.; Uematsu, M.; Hino-Fukuyo, N.; Onuma, A.; Iinuma, K.; Tsuchiya, S. Intramuscular renin-angiotensin system is activated in human muscular dystrophy. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 280, 40–48.

- Zamai, L. The Yin and Yang of ACE/ACE2 Pathways: The Rationale for the Use of Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibitors in COVID-19 Patients. Cells 2020, 9, 1704.

- Dinh, D.T.; Frauman, A.G.; Johnston, C.I.; Fabiani, M.E. Angiotensin receptors: Distribution, signalling and function. Clin. Sci. 2001, 100, 481–492.

- Dostal, D.E.; Baker, K.M. The cardiac renin-angiotensin system: Conceptual, or a regulator of cardiac function? Circ. Res. 1999, 85, 643–650.

- Bader, M. Molecular interactions of vasoactive systems in cardiovascular damage. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2001, 38 (Suppl. 2), S7–S9.