Recent studies have shown various metabolic and transcriptomic interactions between sulfur (S) and phosphorus (P) in plants. However, most studies have focused on the effects of phosphate (Pi) availability and P signaling pathways on S homeostasis, whereas the effects of S availability on P homeostasis remain largely unknown. In this study, we investigated the interactions between S and P from the perspective of S availability. We investigated the effects of S availability on Pi uptake, transport, and accumulation in

Arabidopsis thaliana

grown under sulfur sufficiency (+S) and deficiency (−S). Total P in shoots was significantly increased under −S owing to higher Pi accumulation. This accumulation was facilitated by increased Pi uptake under −S. In addition, −S increased root-to-shoot Pi transport, which was indicated by the increased Pi levels in xylem sap under −S. The −S-increased Pi level in the xylem sap was diminished in the disruption lines of

PHT1;9

and

PHO1, which are involved in root-to-shoot Pi transport. Our findings indicate a new aspect of the interaction between S and P by listing the increased Pi accumulation as part of −S responses and by highlighting the effects of −S on Pi uptake, transport, and homeostasis.

, which are involved in root-to-shoot Pi transport. Our findings indicate a new aspect of the interaction between S and P by listing the increased Pi accumulation as part of −S responses and by highlighting the effects of −S on Pi uptake, transport, and homeostasis.

Note: the results in this article are only parts of the original. To see the full results and details please press here.

- Arabidopsis thaliana

- phosphate accumulation

- phosphate transporters

- phosphorus

- sulfur

- Plant nutrition

- Macronutrient

- nutrients interaction

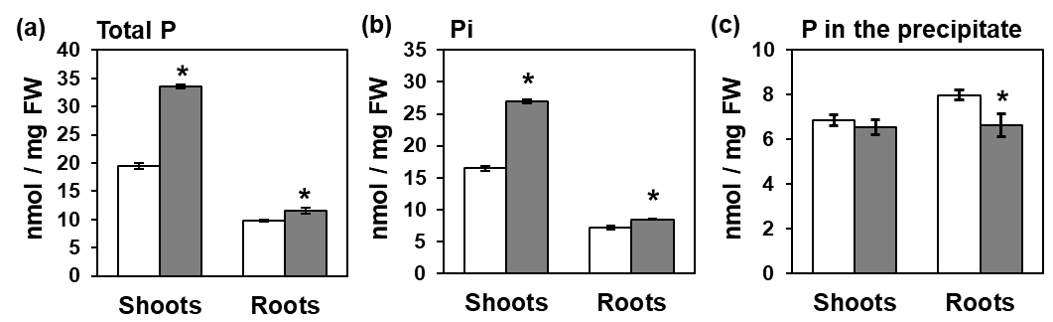

1. Sulfur Deficiency Increased Pi Accumulation in Shoots

To understand the effects of S availability on P accumulation in

Arabidopsis, we analyzed total P and Pi levels in shoots and roots under different S conditions. Total P level increased in both shoots and roots under –S, with a greater change in shoots than in roots (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Arabidopsis

a

b

c

a

b

c

n

t

p < 0.05).

Total P accumulation in shoots reproducibly increased by –S accompanied by the increased Pi level in shoots (Figure 1b). In contrast, P level in the insoluble fraction was not affected by –S in shoots (Figure 1c). These results highlighted Pi accumulation in shoots as part of plant response to –S. Given the vital role of these essential nutrients, the interactions and coordination between S and P in response to their deficiencies could be essentially required to sustain better plant growth and development under these conditions.

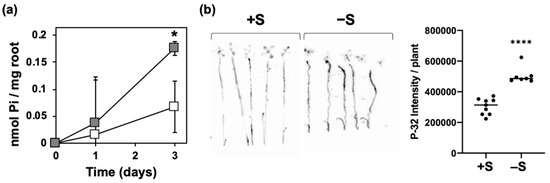

2. Enhancement of Pi Uptake under –S

The increased levels of total P and Pi in shoots suggested a higher Pi acquisition under –S (Figure 1). To support this hypothesis, we analyzed Pi uptake with the two ways of analysis. One was the analysis of Pi withdrawal from the hydroponic media under +S and –S (Figure 2a). Plants were transferred to +S or –S hydroponic media and Pi levels in the media were analyzed at 0, 1, and 3 days after starting the treatment. The decrease of Pi levels in the media from the starting day (0 day) was calculated as the amount of Pi absorbed by the roots. Pi acquisition increased about three-fold under –S compared with that under +S (Figure 2a). With another way of Pi uptake analysis using the radioactive isotope of phosphorus (

32P) (Figure 2b), we also found an enhancement of Pi uptake as an early response to –S.

Figure 2.

a

b

32

a

n

b

n

t

p

a

t

p

b).

Then we tested the transporters to facilitate the −S-increased Pi accumulation using the disruption lines of Pi transporters. The single mutants of

PHT1;1

PHT1;2

PHT1;4, the high-affinity Pi transporters facilitate Pi uptake from roots, increased Pi under -S, suggesting the involvement of several Pi transporters in the increased Pi uptake or another class of Pi transporters. Also, the transcript levels of these transporters were not affected under −S.

3.

Increased Root-to-Shoot Pi Transport under –S contributed to PHT1;9 and PHO1

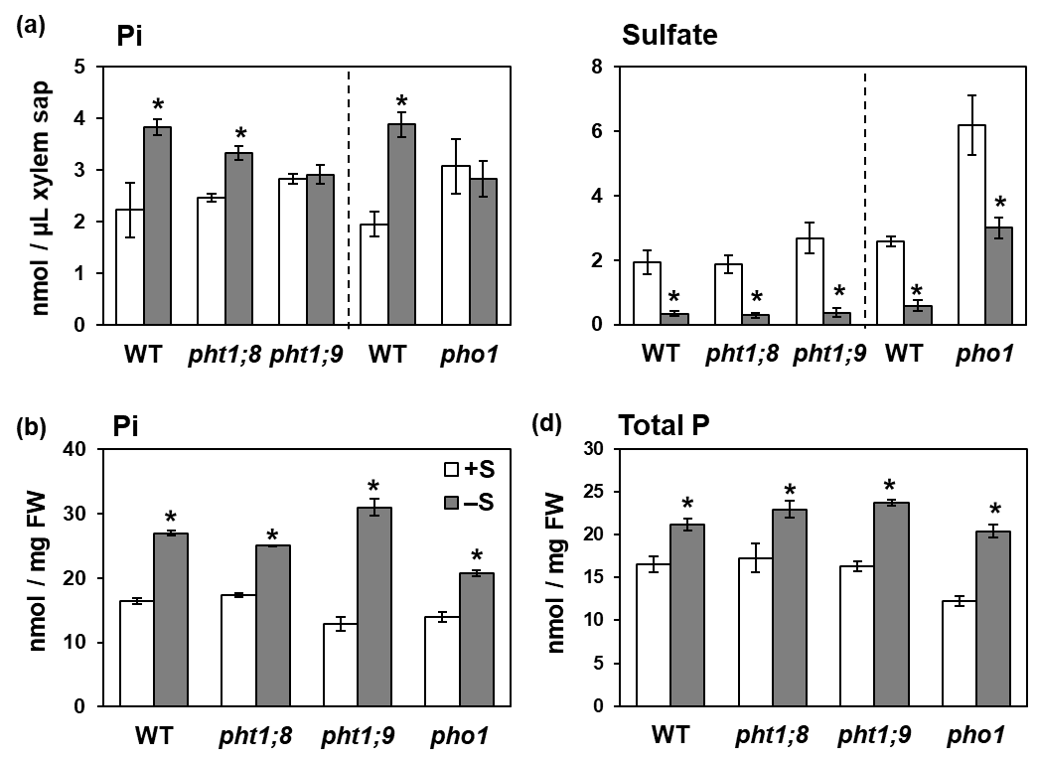

Despite the enhanced Pi uptake under –S, Pi accumulation was remarkably higher in shoots comparing to that in roots, suggesting an enhancement in root-to-shoot Pi transport under –S (Figure 1). Thus, we analyzed Pi level in xylem sap of plants grown under different S conditions (Figure 3a). Plants were transferred to +S or –S hydroponic media and used for the collection of xylem sap. Pi level in xylem sap was significantly increased in WT under –S (Figure 3a), indicating that the root-to-shoot Pi transport was stimulated under –S. In contrast, sulfate level was strongly decreased in xylem sap (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

PHT1;8

PHT1;9

PHO1

a

b

c

n

t

p < 0.05).

Interestingly, the –S-increased Pi level in xylem sap vanished in

pho1

pht1;9

pht1;8

pht1;9

pho1, respectively, disruption of either of them was sufficient to interrupt the –S-increased Pi accumulation in xylem sap (Figure 3a). These results suggest that PHO1 and PHT1;9 possibly work together, either as complex or by regulating one another, to regulate the increased Pi accumulation in xylem sap under −S.

To see how the −S-increased root-to-shoot Pi transport affects the −S-increased Pi accumulation in shoots, we further analyzed total P and Pi levels in

pht1;8

pht1;9

pho1

pht1;9

pho1 (Figure 3a). These results suggested the existence of additional mechanisms underlying the Pi accumulation in shoots under −S other than the increased root-to-shoot Pi transport via PHT1;9 and PHO1.

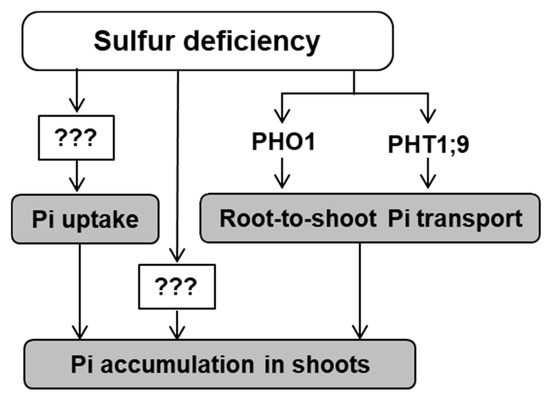

Figure 4. Effects of –S on Pi accumulation, uptake, and transport to shoot. Under –S, higher Pi uptake and Pi transport from roots to shoots were confirmed in this study, which ultimately leads to higher Pi accumulation in shoots under –S listing it as part of –S response in plants. Two transporters, namely, PHT1;9 and PHO1, were found to contribute to the increased Pi transport from root to shoot under –S. Further investigations required to identify the molecular mechanisms regulating the increased Pi uptake and accumulation under –S. Arrows (→) indicates “stimulated by –S”.

As demonstrated by the previous studies on the influences of P deficiency on the S metabolism, the Pi accumulation might be required to sustain plant growth under −S, or it can be an indirect consequence of plant response to −S. At this point, it is difficult to propose the real physiological meaning of the increased Pi accumulation in shoots under −S. In the original article, we confirmed that the increased Pi in shoots and xylem sap was a response to −S, by the re-addition of sulfate to plants subjected to −S. The increased sulfate levels in

pho1

42−

43−), another interesting hypothesis is the requirement of Pi accumulation to maintain the cellular or subcellular ionic balance under −S, vice versa occurs under −P.

The -S-increased Pi uptake and transport to shoots can be regulated by a posttranslational mechanism, which we discussed in the original paper. Several posttranslational regulators are reported to physically interact with PHT1 proteins. Also,

PHT1 members are capable of physically interact in the plasma membrane and form homomeric and heteromeric complexes, in dicot plants, providing an additional posttranslational regulatory mechanism for these transporters. In addition, Pi uptake might be stimulated under −S by the increased number of lateral roots and root hairs, as Pi uptake was reported to be improved by the enhanced lateral root and root hair formation under –P.

- Sakuraba, Y.; Kanno, S.; Mabuchi, A.; Monda, K.; Iba, K.; Yanagisawa, S. A phytochrome-B-mediated regulatory mechanism of phosphorus acquisition. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanno, S.; Cuyas, L.; Javot, H.; Bligny, R.; Gout, E.; Dartevelle, T.; Hanchi, M.; Nakanishi, T.M.; Thibaud, M.-C.; Nussaume, L. Performance and limitations of phosphate wuantification: Guidelines for plant biologists. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, V.; Linhares, F.; Solano, R.; Martín, A.C.; Iglesias, J.; Leyva, A.; Paz-Ares, J. A conserved MYB transcription factor involved in phosphate starvation signaling both in vascular plants and in unicellular algae. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 2122–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos, R.; Castrillo, G.; Linhares, F.; Puga, M.I.; Rubio, V.; Pérez-Pérez, J.; Solano, R.; Leyva, A.; Paz-Ares, J. A central regulatory system largely controls transcriptional activation and repression responses to phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama-Nakashita, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Yamaya, T.; Takahashi, H. A novel regulatory pathway of sulfate uptake in Arabidopsis roots: Implication of CRE1/WOL/AHK4-mediated cytokinin-dependent regulation. Plant J. 2004, 38, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.Y.; Huang, T.K.; Chiou, T.J. Nitrogen Limitation Adaptation, a target of MicroRNA827, mediates degradation of plasma membrane-localized phosphate transporters to maintain phosphate homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 4061–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, J.; Gao, M.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yamaji, N.; Ma, J.F.; et al. The rice CK2 kinase regulates trafficking of phosphate transporters in response to phosphate levels. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Ying, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, C.; Whelan, J.; Shou, H. OsNLA1, a RING-type ubiquitin ligase, maintains phosphate homeostasis in Oryza sativa via degradation of phosphate transporters. Plant J. 2017, 90, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, R.P.; Pant, B.D.; Stitt, M.; Scheible, W.R. PHO2, microRNA399 and PHR1 define a phosphate signalling pathway in plants. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.-Y.; Huang, T.-K.; Tseng, C.-Y.; Lai, Y.-S.; Lin, S.-I.; Lin, W.-Y.; Chen, J.-W.; Chiou, T.-J. PHO2-dependent degradation of PHO1 modulates phosphate homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2168–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-K.; Han, C.-L.; Lin, S.-I.; Chen, Y.-J.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-R.; Chen, J.-W.; Lin, W.-Y.; Chen, P.-M.; Liu, T.-Y.; et al. Identification of downstream components of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme PHOSPHATE2 by quantitative membrane proteomics in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 4044–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.X.; Gu, M.; Xia, Y.W.; Dai, X.L.; Chang, R.D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.C.; Qu, H.Y.; Yamaji, N.; Ma, J.F.; et al. OsPHT1;3 mediates uptake, translocation, and remobilization of phosphate under extremely low phosphate regimes. Plant Physiol. 2019, 179, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.P.; Kumar, H.; Waight, A.B.; Risenmay, A.J.; Roe-Zurz, Z.; Chau, B.H.; Schlessinger, A.; Bonomi, M.; Harries, W.; Sali, A.; et al. Crystal structure of a eukaryotic phosphate transporter. Nature 2013, 496, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, T.J.; Liu, H.; Harrison, M.J. The spatial expression patterns of a phosphate transporter (MtPT1) from Medicago truncatula indicate a role in phosphate transport at the root/soil interface. Plant J. 2001, 25, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontenot, E.B.; DiTusa, S.F.; Kato, N.; Olivier, D.M.; Dale, R.; Lin, W.Y.; Chiou, T.J.; Macnaughtan, M.A.; Smith, A.P. Increased phosphate transport of Arabidopsis thaliana Pht1;1 by site-directed mutagenesis of tyrosine 312 may be attributed to the disruption of homomeric interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, S.; Jones, D.L. Through form to function: Root hair development and nutrient uptake. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Bielenberg, D.G.; Brown, K.M.; Lynch, J.P. Regulation of root hair density by phosphorus availability in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wege, S.; Khan, G.A.; Jung, J.Y.; Vogiatzaki, E.; Pradervand, S.; Aller, I.; Meyer, A.J.; Poirier, Y. The EXS Domain of PHO1 participates in the response of shoots to phosphate deficiency via a root-to-shoot signal. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogiatzaki, E.; Baroux, C.; Jung, J.Y.; Poirier, Y. PHO1 exports phosphate from the chalazal seed coat to the embryo in developing Arabidopsis seeds. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 2893–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouached, H.; Arpat, A.B.; Poirier, Y. Regulation of phosphate starvation responses in plants: Signaling players and cross-talks. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Młodzińska, E.; Zboińska, M. Phosphate uptake and allocation—A closer look at arabidopsis thaliana L. and Oryza sativa L. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]